Century of Progress

| 1933–1934 Chicago | |

|---|---|

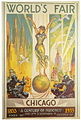

A 1933 Century of Progress World's Fair poster. It was later decided to continue the fair into 1934. This poster features the fair's Federal Building and Hall of States. | |

| Overview | |

| BIE-class | Universal exposition |

| Category | Historical Expo |

| Name | A Century of Progress International Exposition |

| Motto | Science Finds, Industry Applies, Man Conforms |

| Area | 172 hectares (430 acres) |

| Visitors | 48,469,227 |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| City | Chicago |

| Venue | Lakefront, Northerly Island |

| Coordinates | 41°51′38″N 87°36′41″W / 41.86056°N 87.61139°W |

| Timeline | |

| Bidding | 1923 |

| Opening | May 27, 1933 |

| Closure | October 31, 1934 |

| Universal expositions | |

| Previous | Ibero-American Exposition of 1929 in Sevilla and 1929 Barcelona International Exposition in Barcelona |

| Next | Brussels International Exposition (1935) in Brussels |

A Century of Progress International Exposition, also known as the Chicago World's Fair, was a world's fair held in the city of Chicago, Illinois, United States, from 1933 to 1934. The fair, registered under the Bureau International des Expositions (BIE), celebrated the city's centennial. Designed largely in Art Deco style, the theme of the fair was technological innovation, and its motto was "Science Finds, Industry Applies, Man Conforms", trumpeting the message that science and American life were wedded.[1] Its architectural symbol was the Sky Ride, a transporter bridge perpendicular to the shore on which one could ride from one side of the fair to the other.

One description of the fair noted that the world, "then still mired in the malaise of the Great Depression, could glimpse a happier not-too-distant future, all driven by innovation in science and technology". Fair visitors saw the latest wonders in rail travel, automobiles, architecture and even cigarette-smoking robots.[2] The exposition "emphasized technology and progress, a utopia, or perfect world, founded on democracy and manufacturing."[3]

Context

[edit]

A Century of Progress was organized as an Illinois nonprofit corporation in January 1928 for the purpose of planning and hosting a World's Fair in Chicago in 1934. City officials designated three and a half miles of newly reclaimed land along the shore of Lake Michigan between 12th and 39th streets on the Near South Side for the fairgrounds.[4] Held on a 427 acres (1.73 km2) portion of Burnham Park, the $37,500,000 exposition was formally opened on May 27, 1933, by U.S. Postmaster General James Farley at a four-hour ceremony at Soldier Field.[5][6] The fair's opening night began with a nod to the heavens. Lights were automatically activated when the rays of the star Arcturus were detected. The star was chosen as its light had started its journey at about the time of the previous Chicago world's fair—the World's Columbian Exposition—in 1893.[7] The rays were focused on photoelectric cells in a series of astronomical observatories and then transformed into electrical energy which was transmitted to Chicago.[8]

Exhibits

[edit]

The fair buildings were multi-colored, to create a "Rainbow City" as compared to the "White City" of Chicago's earlier World's Columbian Exposition. The buildings generally followed Moderne architecture in contrast to the neoclassical themes used at the 1893 fair. One famous feature of the fair were the performances of fan dancer Sally Rand. Hal Pearl then known as "Chicago's Youngest Organist" and later "The King of the Organ" was the official organist of the fair. Mary Ann McArdle and her sister Isabel (from the UK) performed Irish Dancing. Other popular exhibits were the various auto manufacturers, the Midway (filled with nightclubs such as the Old Morocco, where future stars Judy Garland, the Cook Family Singers, and the Andrews Sisters performed), and a recreation of important scenes from Chicago's history. The fair also contained exhibits that would seem shocking to modern audiences, including offensive portrayals of African Americans, a "Midget City" complete with "sixty Lilliputians",[9] and an exhibition of incubators containing real babies.[10]

The fair included an exhibit on the history of Chicago. In the planning stages, several African American groups from the city's newly growing population campaigned for Jean Baptiste Point du Sable to be honored at the fair.[11] At the time, few Chicagoans had even heard of Point du Sable, and the fair's organizers presented the 1803 construction of Fort Dearborn as the city's historical beginning. The campaign was successful, and a replica of Point du Sable's cabin was presented as part of the "background of the history of Chicago".[11] Also on display was the "Lincoln Group" of reconstructions of buildings associated with the biography of Abraham Lincoln, including his birth cabin, the Lincoln-Berry General Store, the Chicago Wigwam (in reduced scale), and the Rutledge Tavern which served as a restaurant.

Admiral Byrd's polar expedition ship the City of New York was visited by President Franklin D. Roosevelt when he came to the fair on October 2, 1933. The City was on show for the full length of the exhibition.[12]

One of the highlights of the 1933 World's Fair was the arrival of the German airship Graf Zeppelin on October 26, 1933. After circling Lake Michigan near the exposition for two hours, Commander Hugo Eckener landed the 776-foot airship at the nearby Curtiss-Wright Airport in Glenview. It remained on the ground for twenty-five minutes (from 1 to 1:25 pm)[13] then took off ahead of an approaching weather front, bound for Akron, Ohio.

The "dream cars" which American automobile manufacturers exhibited at the fair included Rollston bodywork on a Duesenberg chassis, and was called the Twenty Grand ultra-luxury sedan; Cadillac's introduction of its V-16 limousine; Nash's exhibit had a variation on the vertical (i.e., paternoster lift) parking garage—all the cars were new Nashes; Lincoln presented its rear-engined "concept car" precursor to the Lincoln-Zephyr, which went on the market in 1936 with a front engine; Pierce-Arrow presented its modernistic Pierce Silver Arrow for which it used the byline "Suddenly it's 1940!" But it was Packard which won the best of show with the reintroduction of the Packard Twelve.

An enduring exhibit was the 1933 Homes of Tomorrow Exhibition that demonstrated modern home convenience and creative practical new building materials and techniques with twelve model homes sponsored by several corporations affiliated with home decor and construction.

Marine artist Hilda Goldblatt Gorenstein painted twelve murals for the Navy's exhibit in the Federal Building for the fair. The frieze was composed of twelve murals depicting the influence of sea power on America, beginning with the settlement of Jamestown, Virginia, in 1607 when sea power first reached America and carrying through World War I.[14] Another set of murals, painted for the Ohio State Exhibit by William Mark Young, was relocated afterwards to the Ohio Statehouse.[15][16] Young also painted scenes of the exhibition buildings.

The first Major League Baseball All-Star Game was held at Comiskey Park (home of the Chicago White Sox) in conjunction with the fair.

In May 1934, the Union Pacific Railroad exhibited its first streamlined train, the M-10000, and the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad its famous Zephyr which, on May 26, made a record-breaking dawn-to-dusk run from Denver, Colorado, to Chicago in 13 hours and 5 minutes, called the "Dawn-to-Dusk Dash". To cap its record-breaking speed run, the Zephyr arrived dramatically on-stage at the fair's "Wings of a Century" transportation pageant.[17] The two trains launched an era of industrial streamlining.[18] Both trains later went into successful revenue service, the Union Pacific's as the City of Salina, and the Burlington Zephyr as the first Pioneer Zephyr.[19] The Zephyr is now on exhibit at Chicago's Museum of Science and Industry.[20]

Frank Buck furnished a wild animal exhibit, Frank Buck's Jungle Camp. Over two million people visited Buck's reproduction of the camp he and his native assistants lived in while collecting animals in Asia. After the fair closed, Buck moved the camp to a compound he had created at Amityville, New York.[21]

Architecture

[edit]

Planning for the design of the Exposition began over five years prior to Opening Day.[22] According to an official resolution, decisions regarding the site layout and the architectural style of the exposition were relegated to an architectural commission, which was led by Paul Cret and Raymond Hood.[23] Local architects on the committee included Edward Bennett, John Holabird, and Hubert Burnham. Frank Lloyd Wright was specifically left off the commission due to his inability to work well with others, but did go on to produce three conceptual schemes for the fair.[24][25] Members of this committee ended up designing most of the large, thematic exhibition pavilions.[26]

From the beginning, the commission members shared a belief that the buildings should not reinterpret past architectural forms – as had been done at earlier fairs, such as Chicago's 1893 World's Columbian Exposition—but should instead reflect new, modern ideas, as well as suggest future architectural developments.[27] Because the fairgrounds was on new man-made land that was owned by the state and not the city, the land was initially free from Chicago's strict building codes, which allowed the architects to explore new materials and building techniques.[28] This allowed the design and construction of a wide array of experimental buildings, that eventually included large general exhibition halls, such as the Hall of Science (Paul Cret) and the Federal Building (Bennet, Burnham, and Holabird); corporate pavilions, including the General Motors Building (Albert Kahn) and the Sears Pavilion (Nimmons, Carr, and Wright); futuristic model houses, most popular was the twelve-sided House of Tomorrow (George Frederick Keck); as well as progressive foreign pavilions, including the Italian Pavilion (Mario de Renzi and Adalberto Libera); and historic and ethnic entertainment venues, such as the Belgian Village (Burnham Brothers with Alfons De Rijdt),[29] and the Streets of Paris (Andrew Rebori and John W. Root) where fan dancer Sally Rand performed.[30] These buildings were constructed out of five-ply Douglas fir plywood, ribbed-metal siding, and prefabricated boards such as Masonite, Sheetrock, Maizewood, as well as other new man-made materials.[31] The exhibited buildings were windowless (but cheerfully lighted) buildings.[32] Structural advances also filled the fairgrounds. These included the earliest catenary roof constructed in the United States, which roofed the dome of the Travel and Transport Building (Bennet, Burnham and Holabird) and the first thin shell concrete roof in the United States, on the small, multi-vaulted Brook Hill Farm Dairy built for the 1934 season of the fair.[33]

Later history

[edit]Amoebic dysentery outbreak

[edit]From June to November 1933, there was an outbreak of amoebic dysentery associated with the fair. There were more than a thousand cases, resulting in 98 deaths.[34][35][36] Joel Connolly of the Chicago Bureau of Sanitary Engineering brought the outbreak to an end when he found that defective plumbing permitted sewage to contaminate drinking water in two hotels.

Extension

[edit]Originally, the fair was scheduled only to run until November 12, 1933, but it was so successful that it was opened again to run from May 26 to October 31, 1934.[37] The fair was financed through the sale of memberships, which allowed purchases of a certain number of admissions once the park was open. More than $800,000 was raised in this manner as the country was in the Great Depression. A $10 million bond was issued on October 28, 1929, the day before the stock market crashed. By the time the fair closed in 1933, half of these notes had been retired, with the entire debt paid by the time the fair closed in 1934. For the first time in American history, an international fair had paid for itself. In its two years, it had attracted 48,769,227 visitors. According to James Truslow Adams's Dictionary of American History, during the 170 days beginning May 27, 1933, there were 22,565,859 paid admissions; during the 163 days beginning May 26, 1934, there were 16,486,377; a total of 39,052,236.[38]

Legacy

[edit]

Much of the fair site is now home to Northerly Island park (since the closing of Meigs Field) and McCormick Place. The Balbo Monument, given to Chicago by Benito Mussolini to honor General Italo Balbo's 1933 trans-Atlantic flight, still stands near Soldier Field. The city added a third red star to its flag in 1933 to commemorate the Century of Progress Exposition (the Fair is now represented by the fourth of four stars on the flag).[39] In conjunction with the fair, Chicago's Italian-American community raised funds and donated a statue of Genoese navigator and explorer Christopher Columbus.[40] It was placed at the south end of Grant Park, near the site of the fair.

The Polish Museum of America possesses the painting of Pulaski at Savannah by Stanisław Kaczor-Batowski, which was exhibited at the Century of Progress fair and where it won first place. After the close of the fair, the painting went on display at The Art Institute of Chicago where it was unveiled by Eleanor Roosevelt on July 10, 1934. The painting was on display at the Art Institute until its purchase by the Polish Women's Alliance on the museum's behalf.[41]

The U.S. Post Office Department issued a special fifty-cent Air Mail postage stamp, (Scott catalogue number C-18) to commemorate the visit of the German airship depicting (l to r) the fair's Federal Building, the Graf Zeppelin in flight, and its home hangar in Friedrichshafen, Germany. This stamp is informally known as the Baby Zep to distinguish it from the much more valuable 1930 Graf Zeppelin stamps (C13–15). Separate from this issue, for the Fair the Post Office also printed 1 and 3 cent commemorative postage stamps, showing respectively Fort Dearborn and the modernistic Federal Building. These were also printed in separate souvenir sheets as blocks of 25 (catalog listings 728–31). In 1935 the sheets were reprinted (Scott 766–67).

From October 2010 through September 2011, the National Building Museum in Washington, D.C. opened an exhibition titled Designing Tomorrow: America's World's Fairs of the 1930s.[42] This exhibition prominently featured the Century of Progress fair in Chicago.

In popular culture

[edit]- Nelson Algren's 1935 novel Somebody in Boots features the Chicago World's Fair of 1933–34, with the Century of Progress being described as "the brief city sprung out of the prairie and falling again into dust."[43]

- Jean Shepherd wrote about attending the Century of Progress as a boy in the 1966 book In God We Trust: All Others Pay Cash[44]

- Roy J. Snell, author of books for boys and girls, used Chicago, the building of the Fair site, the Fair itself -including the Sky Ride – and then certain portions of the Fair after it closed in several of his books. Publisher, Reilly & Lee. Books now in Public Domain.[citation needed]

- Beverly Gray at the World's Fair, originally the sixth book in Clair Blank's Beverly Gray series, was published in 1935 and is set at the Century of Progress. The book was dropped when the series changed publishers due to fears that readers would find it dated, and has since become a sought after volume by collectors of the series.[citation needed]

- In True Detective, the 1983 private eye novel by Max Allan Collins, and the first to feature his long-running character Nate Heller, Heller is hired as a security consultant by the Fair, and a good deal of the novel is set there. The suspenseful action climax takes place at the Fair. The novel went on to win the Shamus from the Private Eye Writers of America for Best Novel.[45]

- Brief footage of the fairground sideshows is used in the 1933 film Hoop-La, the plot of which revolves around the fair. It was the last film made by Clara Bow. Also shown is a panorama of the Century of Progress concourse.[citation needed]

- In her novel The Fountainhead, Ayn Rand describes a world fair named The March of the Centuries. Despite having taken place in 1936, The March of the Centuries bears a striking similarity to the Century of Progress exposition: it, too, is designed by a group of architects; architect Howard Roark was initially invited but later denied opportunity to participate in planning (as his prototype Frank Lloyd Wright was left off the commission), the fair opened in May. Rand described the fair as "a ghastly flop" and mentioned that its only attraction was "somebody named Juanita Fay who danced with a live peacock as sole garment" (a description clearly based on Sally Rand's performance).[46]

- In Neal Stephenson's 2024 novel Polostan, the main character works as a shoe model and salesperson for a shop on the fairway that fits shoes using an X-ray machine. She sees the arrival of the Decennial Air Cruise and events in Soldier's Field.

Resources

[edit]The major archive for the Century of Progress International Exposition, including the official records from the event and the papers of Lenox Lohr, general manager of the fair, are housed in Special Collections at the University of Illinois, Chicago. A collection of materials including images is held by the Ryerson & Burnham Libraries at the Art Institute of Chicago. The Century of Progress Collection includes photographs, guidebooks, brochures, maps, architectural drawings, and souvenir items. Specific collections with material include the Chicago Architects Oral History Project; the Daniel H. Burnham Jr. and Hubert Burnham Papers; Edward H. Bennett Collection; Voorhees, Gmelin, and Walker photographs.

Gallery

[edit]-

Mural General Exhibit 3rd pavilion

-

One of the eagles that stood on pedestals along Lakeshore Drive and Michigan Avenue in Downtown Chicago during the World's Fair.

-

Poster for the fair by Glen C. Sheffer.

-

Ground Plan for the Exhibit showing name and location of most exhibits. From the files of Assistant Ticket Manager Joseph W Baker.

-

Japanese official pavilion buildings at the 1933 World's Fair, with gardens constructed by Chicago Japanese garden builder T.R. Otsuka

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "World's Fairs 1933–1939". Historic Events for Students: The Great Depression. encyclopedia. March 6, 2019. Archived from the original on March 7, 2019. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- ^ LaMorte, Chris (October 2, 2017). "Century of Progress Homes Tour at Indiana Dunes takes visitors back to the future". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on October 3, 2017. Retrieved October 2, 2017.

- ^ "World's Fairs 1933–1939". Historic Events for Students: The Great Depression. Encyclopedia. February 25, 2019. Archived from the original on March 7, 2019. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- ^ Schrenk, Lisa D. (2007). Building a Century of Progress: The Architecture of the 1933–34 Chicago World's FairUniversity of Minnesota Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0816648368.

- ^ Chicago Fair Opened by Farley; Rays of Arcturus Start Lights. Postmaster General Conveys President's Hope That Exposition Will Help Friendship Among Nations—First Day's Attendance Estimated at About 250,000. The New York Times, May 28, 1933, p. 1

- ^ Chicago and Suburbs 1939. Works Progress Administration. 1939. p. 105.

- ^ "Century of Progress World's Fair, 1933–1934". University of Illinois-Chicago. January 2008. Archived from the original on July 18, 2011. Retrieved September 6, 2009.

- ^ Marche II, Jordan D. (June 8, 2005). Theaters of Time and Space: American Planetaria, 1930–1970. Rutgers University Press. p. 80. ISBN 978-0-8135-3576-0. Archived from the original on April 25, 2016. Retrieved September 3, 2012.

- ^ Raabe, Meinhardt; Daniel Kinske (2005). Memories of a Munchkin. New York: Back Stage Books. ISBN 0-8230-9193-7.

- ^ Baby Incubators, Omaha Public Library Archived August 26, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b Reed, Christopher R. (June 1991). "'In the Shadow of Fort Dearborn': Honoring De Saible at the Chicago World's Fair of 1933–1934". Journal of Black Studies. 21 (4): 398–413. doi:10.1177/002193479102100402. JSTOR 2784685. S2CID 145599165.

- ^ "Itinerary for FDR's trip to the Chicago World's Fair". fdrlibrary.marist.edu. Archived from the original on June 5, 2018. Retrieved June 3, 2018.

- ^ Senkus, William M. (2002). "Cinderella Stamps of the Century of Progress Expo in Chicago, Illinois". alphabetilately.org. Archived from the original on April 30, 2016. Retrieved November 9, 2017.

- ^ McDowell, Malcolm (May 6, 1933). "U.S. Navy Exhibits Arrive for Fair; Models to Show Sea's Influence on Nation". Chicago Daily News. University of Illinois at Chicago archive. Archived from the original on June 27, 2009.

- ^ "Young, William Mark (March 18, 1881 – January 1, 1946): Geographicus Rare Antique Maps". Geographicus. Retrieved November 19, 2022.

- ^ Northwest Territory Celebration Commission (1938). Final Report of the Northwest Territory Celebration Commission (PDF). pp. 10–11, 47–50.

- ^ "Pioneer Zephyr – A Legendary History". excerpts from the New York Times. Chicago Museum of Science and Industry. May 27, 1934. Archived from the original on February 8, 2005. Retrieved February 24, 2005.

- ^ Zimmermann, Karl (2004). Burlington's Zephyrs. Saint Paul, Minnesota: MBI Publishing Company. pp. 16, 26. ISBN 978-0-7603-1856-0.

- ^ Schafer, Mike; Welsh, Joe (1997). Classic American Streamliners. Osceola, Wisconsin: MBI Publishing. p. 14. ISBN 0-7603-0377-0. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021..

- ^ "All Aboard the Pioneer Zephyr". MSI Chicago. Archived from the original on November 19, 2019. Retrieved June 29, 2018.

- ^ Frank Buck's Jungleland Archived July 16, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ For a detailed discussion of the architecture of the Century of Progress International Expositions, see Schrenk, Lisa D. (2007). Building a Century of Progress: The Architecture of the 1933–34 Chicago World's Fair. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0816648368.

- ^ Chicago World's Fair Centennial Celebration of 1933 Board of Trustees, Resolution, February 21, 1928, Available in the Century of Progress Archive, University of Illinois, Chicago.

- ^ Raymond Hood to Frank Lloyd Wright, Letter, February 16, 1931, Taliesin Archives, Avery Library, Columbia University.

- ^ For more on Frank Lloyd Wright and the Century of Progress see Lisa D. Schrenk (2007). Building a Century of Progress: The Architecture of the 1933–34 Chicago World's Fair. University of Minnesota Press. p. 188-199 ISBN 978-0816648368

- ^ Schrenk, Lisa D. (2007). Building a Century of Progress: The Architecture of the 1933–34 Chicago World's Fair. University of Minnesota Press. p. 70. ISBN 978-0816648368.

- ^ Schrenk, Lisa D. (2007). Building a Century of Progress: The Architecture of the 1933–34 Chicago World's Fair. University of Minnesota Press. p. 47. ISBN 978-0816648368.

- ^ S. L. Tesone to C.W. Farrier and J. Stewart, Memo, October 16, 1933, p. 65, Century of Progress Archive, University of Illinois, Chicago.

- ^ Coomans, Thomas (2020). A Complex Identity Picturesquely Staged. The 'Belgian Village' at the Century of Progress Exhibition, Chicago 1933, Revue Belge d'Archéologie et d'Histoire de l'Art, 89, p. 141-172. ISSN 0035-077X.

- ^ Schrenk, Lisa D. (2007). Building a Century of Progress: The Architecture of the 1933–34 Chicago World's Fair. University of Minnesota Press. p. 265. ISBN 978-0816648368.

- ^ Schrenk, Lisa D. (2007). Building a Century of Progress: The Architecture of the 1933–34 Chicago World's Fair. University of Minnesota Press. p. 130-131. ISBN 978-0816648368.

- ^ "World Fairs 1933–1939". Historic Events for Students: The Great Depression, Encyclopedia. February 25, 2019. Archived from the original on March 7, 2019. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- ^ Schrenk, Lisa D. (2007). Building a Century of Progress: The Architecture of the 1933–34 Chicago World's Fair. University of Minnesota Press. p.40. ISBN 978-0816648368

- ^ Markell, E.K. (June 1986). "The 1933 Chicago outbreak of amebiasis". Western Journal of Medicine. 144 (6): 750. PMC 1306777. PMID 3524005.

- ^ "Water and Waste Systems". Archived from the original on January 19, 2017. Retrieved January 19, 2017.

- ^ "2022 National Backflow Prevention Day!". Arbiter Backflow. August 16, 2022. Retrieved October 1, 2023.

- ^ Rydell, Robert W. (2005). "Century of Progress Exposition". Encyclopedia of Chicago. Archived from the original on May 14, 2011. Retrieved May 10, 2011.

- ^ "1933 Chicago". www.bie-paris.org. Retrieved February 12, 2024.

- ^ "Municipal Flag of Chicago". Chicago Public Library. 2009. Archived from the original on June 15, 2013. Retrieved March 4, 2009.

- ^ "Christopher Columbus" (PDF). Chicago Park District. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 6, 2011. Retrieved July 1, 2011.

- ^ The Polish Museum of America – History and Collections – Guide, p.31 Argraf, Warsaw, 2003

- ^ "Designing Tomorrow: America's World's Fairs of the 1930s". National Building Museum. February 7, 2017. Archived from the original on February 1, 2018. Retrieved January 31, 2018.

- ^ Blades, John (May 10, 1987). "Nelson Algren's 'Boots' Still Has A Powerful Kick". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on August 8, 2012. Retrieved September 7, 2011.

- ^ "In God We Trust by Jean Shepherd: 9780385021746 | PenguinRandomHouse.com: Books". PenguinRandomhouse.com. Archived from the original on June 4, 2020. Retrieved June 4, 2020.

- ^ Randisi, Robert J. (February 10, 2015). Fifty Shades of Grey Fedora: The Private Eye Writers of America Presents. Riverdale Avenue Books LLC. ISBN 978-1-62601-153-3. Archived from the original on October 20, 2021. Retrieved July 21, 2020.

- ^ Rand, Ayn (1994). The Fountainhead. HarperCollinsPublishers. ISBN 978-0-586-01264-2.

External links

[edit]- Official website of the BIE

- 1933/1934 Chicago World's Fair website

- Chicago World's Fair: A Century of Progress International Exposition – 1933/34 in Postcards

- Panoramic photograph of Century of Progress (from Library of Congress website)

- Website dedicated to the 1933–1934 Century of Progress

- Photographs of Graf Zeppelin over Chicago

- Century of progress Brownie camera on www.BROWNIE.camera

- 1933 Century of Progress Digital Collection from the University of Chicago

- Burnham, Beaux-Arts, Plan of Chicago, & Fairs

- Chicago Art Deco Society

- Florida Pavilion – Chicago World's Fair 1933

- A Century of Progress Records at the University of Illinois at Chicago

- Century of Progress images from University of Illinois at Chicago digital collections

- History Detectives . Investigations – Sideshow Babies | PBS

- "The Miracle of Light at the World's Fair" Popular Mechanics, October 1934, pp. 497–512

- "Three Little Maids draw a crowd of 10,000 at Chicago's World's Fair", Chicago Tribune, October 1933