Zeta Leporis

| Observation data Epoch J2000.0 Equinox J2000.0 | |

|---|---|

| Constellation | Lepus |

| Right ascension | 05h 46m 57.34096s[1] |

| Declination | −14° 49′ 19.0199″[1] |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | 3.524[2] |

| Characteristics | |

| Spectral type | A2 IV-V(n)[3] |

| U−B color index | +0.113[2] |

| B−V color index | +0.114[2] |

| Astrometry | |

| Radial velocity (Rv) | 20.0[4]–24.7[5] km/s |

| Proper motion (μ) | RA: -14.54[1] mas/yr Dec.: -1.07[1] mas/yr |

| Parallax (π) | 46.28 ± 0.16 mas[1] |

| Distance | 70.5 ± 0.2 ly (21.61 ± 0.07 pc) |

| Absolute magnitude (MV) | +1.88[6] |

| Details | |

| Mass | 1.46[7] M☉ |

| Radius | 1.5[8] R☉ |

| Luminosity | 14[9] L☉ |

| Surface gravity (log g) | 4.41[9] cgs |

| Temperature | 9,772[10] K |

| Metallicity [Fe/H] | –0.76[3] dex |

| Rotational velocity (v sin i) | 245[8] km/s |

| Age | 231+126 −181[10] Myr |

| Other designations | |

| Database references | |

| SIMBAD | data |

| ARICNS | data |

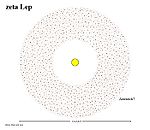

Zeta Leporis, Latinized from ζ Leporis, is a star approximately 70.5 light-years (21.6 parsecs) away in the southern constellation of Lepus. It has an apparent visual magnitude of 3.5,[2] which is bright enough to be seen with the naked eye. In 2001, an asteroid belt was confirmed to orbit the star.

Stellar components

[edit]Zeta Leporis has a stellar classification of A2 IV-V(n),[3] suggesting that it is in a transitional stage between an A-type main-sequence star and a subgiant. The (n) suffix indicates that the absorption lines in the star's spectrum appear nebulous because it is spinning rapidly, causing the lines to broaden because of the Doppler effect. The projected rotational velocity is 245 km/s,[8] giving a lower limit on the star's actual equatorial azimuthal velocity.

The star has about 1.46 times the mass of the Sun,[7] along with 1.5 times the radius,[8] and 14 times the luminosity.[9] The abundance of elements other than hydrogen and helium, what astronomers term the star's metallicity, is only 17% of the abundance in the Sun.[3] The star appears to be very young, probably around 231 million years in age, but the margin of error spans 50–347 million years old.[10]

Asteroid belt

[edit]In 1983, based on radiation in the infrared portion of the electromagnetic spectrum, the InfraRed Astronomical Satellite was used to identify dust orbiting this star. This debris disk is constrained to a diameter of 12.2 AU.[12]

By 2001, the Long Wavelength Spectrometer at the Keck Observatory on Mauna Kea, Hawaii, was used more accurately to constrain the radius of the dust. It was found to lie within a 5.4 AU radius.[12] The temperature of the dust was estimated as about 340 K.[citation needed] Based on heating from the star, this could place the grains as close as 2.5 AU from Zeta Leporis.[12]

It is now believed[by whom?] that the dust is coming from a massive asteroid belt in orbit around Zeta Leporis, making it the first extra-solar asteroid belt to be discovered. The estimated mass of the belt is about 200 times the total mass in the Solar System's asteroid belt, or 4×1023 kg. For comparison, this is more than half the total mass of the Moon. Astronomers Christine Chen and professor Michael Jura found that the dust contained within this belt should have fallen into the star within 20,000 years, a time period much shorter than Zeta Leporis's estimated age, suggesting that some mechanism must be replenishing the belt.[12] The belt's age is estimated to be 3×108 years.[citation needed]

| Companion (in order from star) |

Mass | Semimajor axis (AU) |

Orbital period (days) |

Eccentricity | Inclination | Radius |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asteroid belt | 2.5–6.1 AU | — | — | |||

Solar encounter

[edit]Bobylev's calculations from 2010 suggest that this star passed as close as 1.28 parsecs (4.17 light-years) from the Sun about 861,000 years ago.[5] García-Sánchez 2001 suggested that the star passed 1.64 parsecs (5.34 light-years) from the Sun about 1 million years ago.[4] It was the brightest star in the night sky over 1 million years ago,[13] peaking with an apparent magnitude of -2.05.[13]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e van Leeuwen, F. (November 2007). "Validation of the new Hipparcos reduction". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 474 (2): 653–664. arXiv:0708.1752. Bibcode:2007A&A...474..653V. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20078357. S2CID 18759600.

- ^ a b c d Gutierrez-Moreno, Adelina; et al. (1966), "A System of photometric standards", Publications of the Department of Astronomy University of Chile, 1, Publicaciones Universidad de Chile, Department de Astronomy: 1–17, Bibcode:1966PDAUC...1....1G

- ^ a b c d Gray, R. O.; et al. (July 2006), "Contributions to the Nearby Stars (NStars) Project: spectroscopy of stars earlier than M0 within 40 pc-The Southern Sample", The Astronomical Journal, 132 (1): 161–170, arXiv:astro-ph/0603770, Bibcode:2006AJ....132..161G, doi:10.1086/504637, S2CID 119476992

- ^ a b García-Sánchez, J.; Weissman, P. R.; Preston, R. A.; Jones, D. L.; Lestrade, J.-F.; Latham, D. W.; Stefanik, R. P.; Paredes, J. M. (2001). "Stellar encounters with the solar system". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 379 (2): 634–659. Bibcode:2001A&A...379..634G. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20011330.

- ^ a b Bobylev, Vadim V. (March 2010). "Searching for Stars Closely Encountering with the Solar System". Astronomy Letters. 36 (3): 220–226. arXiv:1003.2160. Bibcode:2010AstL...36..220B. doi:10.1134/S1063773710030060. S2CID 118374161.

- ^ Anderson, E.; Francis, Ch. (2012), "XHIP: An extended hipparcos compilation", Astronomy Letters, 38 (5): 331, arXiv:1108.4971, Bibcode:2012AstL...38..331A, doi:10.1134/S1063773712050015, S2CID 119257644.

- ^ a b Shaya, Ed J.; Olling, Rob P. (January 2011), "Very Wide Binaries and Other Comoving Stellar Companions: A Bayesian Analysis of the Hipparcos Catalogue", The Astrophysical Journal Supplement, 192 (1): 2, arXiv:1007.0425, Bibcode:2011ApJS..192....2S, doi:10.1088/0067-0049/192/1/2, S2CID 119226823

- ^ a b c d Akeson, R. L.; et al. (February 2009), "Dust in the inner regions of debris disks around a stars", The Astrophysical Journal, 691 (2): 1896–1908, arXiv:0810.3701, Bibcode:2009ApJ...691.1896A, doi:10.1088/0004-637X/691/2/1896, S2CID 12033751

- ^ a b c Malagnini, M. L.; Morossi, C. (November 1990), "Accurate absolute luminosities, effective temperatures, radii, masses and surface gravities for a selected sample of field stars", Astronomy and Astrophysics Supplement Series, 85 (3): 1015–1019, Bibcode:1990A&AS...85.1015M

- ^ a b c Song, Inseok; et al. (February 2001), "Ages of A-Type Vega-like Stars from uvbyβ Photometry", The Astrophysical Journal, 546 (1): 352–357, arXiv:astro-ph/0010102, Bibcode:2001ApJ...546..352S, doi:10.1086/318269, S2CID 18154947

- ^ "Gliese 217.1". SIMBAD Astronomical Object Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 2010-03-19.

- ^ a b c d Morledge, Paul (November 2001). "Tightening a Star's Belt". Astronomy. 29 (11). Kalmbach Publishing: 26. ISSN 0091-6358.

- ^ a b Tomkin, Jocelyn (April 1998). "Once and Future Celestial Kings". Sky and Telescope. 95 (4): 59–63. Bibcode:1998S&T....95d..59T. – based on computations from HIPPARCOS data. (The calculations exclude stars whose distance or proper motion is uncertain.) PDF[permanent dead link]

Further reading

[edit]- Cote J (1987). "B and A type stars with unexpectedly large colour excesses at IRAS wavelengths". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 181 (1): 77–84. Bibcode:1987A&A...181...77C.

- Aumann H. H.; Probst R. G. (1991). "Search for Vega-like nearby stars with 12 micron excess". Astrophysical Journal. 368: 264–271. Bibcode:1991ApJ...368..264A. doi:10.1086/169690.

- Chen C. H.; Jura M. (2001). "A Possible Massive Asteroid Belt around zeta Leporis". Astrophysical Journal. 560 (2): L171. arXiv:astro-ph/0109216. Bibcode:2001ApJ...560L.171C. doi:10.1086/324057. S2CID 40959018.

- M. M. Moerchen; C. M. Telesco; C. Packham; T. J. J. Kehoe (2006). "Mid-infrared resolution of a 3 AU-radius debris disk around Zeta Leporis". Astrophysical Journal Letters. 655 (2): L109. arXiv:astro-ph/0612550. Bibcode:2007ApJ...655L.109M. doi:10.1086/511955. S2CID 18073836.

External links

[edit]- Britt, Robert Roy (2001-06-04). "Asteroid Belt Like Ours Spotted Around Another Star". SPACE.com. Archived from the original on 2008-05-12. Retrieved 2008-06-26.

- UCLA astronomers identify evidence of asteroid belt around nearby star: Findings indicate potential for planet or asteroid formation, 2001.

- "Zeta Leporis". SolStation. Retrieved 2008-06-26.

- Wikisky image of Zeta Leporis