Epsilon Eridani

Epsilon Eridani (Latinized from ε Eridani), proper name Ran,[17] is a star in the southern constellation of Eridanus. At a declination of −9.46°, it is visible from most of Earth's surface. Located at a distance 10.5 light-years (3.2 parsecs) from the Sun, it has an apparent magnitude of 3.73, making it the third-closest individual star (or star system) visible to the naked eye.

The star is estimated to be less than a billion years old.[18] This relative youth gives Epsilon Eridani a higher level of magnetic activity than the Sun, with a stellar wind 30 times as strong. The star's rotation period is 11.2 days at the equator. Epsilon Eridani is smaller and less massive than the Sun, and has a lower level of elements heavier than helium.[19] It is a main-sequence star of spectral class K2, with an effective temperature of about 5,000 K (8,500 °F), giving it an orange hue. It is a candidate member of the Ursa Major moving group of stars, which share a similar motion through the Milky Way, implying these stars shared a common origin in an open cluster.

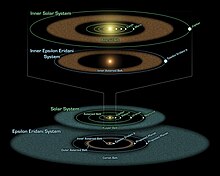

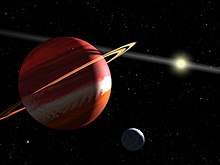

Periodic changes in Epsilon Eridani's radial velocity have yielded evidence of a giant planet orbiting it, designated Epsilon Eridani b.[20] The discovery of the planet was initially controversial,[21] but most astronomers now regard the planet as confirmed. In 2015 the planet was given the proper name AEgir [sic].[22] The Epsilon Eridani planetary system also includes a debris disc consisting of a Kuiper belt analogue at 70 au from the star and warm dust between about 3 au and 20 au from the star.[23][24] The gap in the debris disc between 20 and 70 au implies the likely existence of outer planets in the system.

As one of the nearest Sun-like stars,[25] Epsilon Eridani has been the target of several observations in the search for extraterrestrial intelligence. Epsilon Eridani appears in science fiction stories and has been suggested as a destination for interstellar travel.[26] From Epsilon Eridani, the Sun would appear as a star in Serpens, with an apparent magnitude of 2.4.[note 1]

Nomenclature

[edit]ε Eridani, Latinised to Epsilon Eridani, is the star's Bayer designation. Despite being a relatively bright star, it was not given a proper name by early astronomers. It has several other catalogue designations. Upon its discovery, the planet was designated Epsilon Eridani b, following the usual designation system for extrasolar planets.

The planet and its host star were selected by the International Astronomical Union (IAU) as part of the NameExoWorlds competition for giving proper names to exoplanets and their host stars, for some systems that did not already have proper names.[27][28] The process involved nominations by educational groups and public voting for the proposed names.[29] In December 2015, the IAU announced the winning names were Ran for the star and AEgir [sic] for the planet.[22] Those names had been submitted by the pupils of the 8th Grade at Mountainside Middle School in Colbert, Washington, United States. Both names derive from Norse mythology: Rán is the goddess of the sea and Ægir, her husband, is the god of the ocean.[30]

In 2016, the IAU organised a Working Group on Star Names (WGSN)[31] to catalogue and standardise proper names for stars. In its first bulletin of July 2016,[32] the WGSN explicitly recognised the names of exoplanets and their host stars that were produced by the competition. Epsilon Eridani is now listed as Ran in the IAU Catalog of Star Names.[17] Professional astronomers have mostly continued to refer to the star as Epsilon Eridani.[33]

In Chinese, 天苑 (Tiān Yuàn), meaning Celestial Meadows, refers to an asterism consisting of ε Eridani, γ Eridani, δ Eridani, π Eridani, ζ Eridani, η Eridani, π Ceti, τ1 Eridani, τ2 Eridani, τ3 Eridani, τ4 Eridani, τ5 Eridani, τ6 Eridani, τ7 Eridani, τ8 Eridani and τ9 Eridani.[34] Consequently, the Chinese name for ε Eridani itself is 天苑四 (Tiān Yuàn sì, the Fourth [Star] of Celestial Meadows.)[35]

Observational history

[edit]

Cataloguing

[edit]Epsilon Eridani has been known to astronomers since at least the 2nd century AD, when Claudius Ptolemy (a Greek astronomer from Alexandria, Egypt) included it in his catalogue of more than a thousand stars. The catalogue was published as part of his astronomical treatise the Almagest. The constellation Eridanus was named by Ptolemy – Ποταμού (Ancient Greek for 'River'), and Epsilon Eridani was listed as its thirteenth star. Ptolemy called Epsilon Eridani ό τών δ προηγούμενος (Ancient Greek for 'a foregoing of the four') (here δ is the number four). This refers to a group of four stars in Eridanus: γ, π, δ and ε (10th–13th in Ptolemy's list). ε is the most western of these, and thus the first of the four in the apparent daily motion of the sky from east to west. Modern scholars of Ptolemy's catalogue designate its entry as "P 784" (in order of appearance) and "Eri 13". Ptolemy described the star's magnitude as 3.[36][37]

Epsilon Eridani was included in several star catalogues of medieval Islamic astronomical treatises, which were based on Ptolemy's catalogue: in Al-Sufi's Book of Fixed Stars, published in 964, Al-Biruni's Mas'ud Canon, published in 1030, and Ulugh Beg's Zij-i Sultani, published in 1437. Al-Sufi's estimate of Epsilon Eridani's magnitude was 3. Al-Biruni quotes magnitudes from Ptolemy and Al-Sufi (for Epsilon Eridani he quotes the value 4 for both Ptolemy's and Al-Sufi's magnitudes; original values of both these magnitudes are 3). Its number in order of appearance is 786.[38] Ulugh Beg carried out new measurements of Epsilon Eridani's coordinates in his observatory at Samarkand, and quotes magnitudes from Al-Sufi (3 for Epsilon Eridani). The modern designations of its entry in Ulugh Beg's catalogue are "U 781" and "Eri 13" (the latter is the same as Ptolemy's catalogue designation).[36][37]

In 1598 Epsilon Eridani was included in Tycho Brahe's star catalogue, republished in 1627 by Johannes Kepler as part of his Rudolphine Tables. This catalogue was based on Tycho Brahe's observations of 1577–1597, including those on the island of Hven at his observatories of Uraniborg and Stjerneborg. The sequence number of Epsilon Eridani in the constellation Eridanus was 10, and it was designated Quae omnes quatuor antecedit (Latin for 'which precedes all four'); the meaning is the same as Ptolemy's description. Brahe assigned it magnitude 3.[36][39]

Epsilon Eridani's Bayer designation was established in 1603 as part of the Uranometria, a star catalogue produced by German celestial cartographer Johann Bayer. His catalogue assigned letters from the Greek alphabet to groups of stars belonging to the same visual magnitude class in each constellation, beginning with alpha (α) for a star in the brightest class. Bayer made no attempt to arrange stars by relative brightness within each class. Thus, although Epsilon is the fifth letter in the Greek alphabet,[40] the star is the tenth-brightest in Eridanus.[41] In addition to the letter ε, Bayer had given it the number 13 (the same as Ptolemy's catalogue number, as were many of Bayer's numbers) and described it as Decima septima (Latin for 'the seventeenth').[note 2] Bayer assigned Epsilon Eridani magnitude 3.[42]

In 1690 Epsilon Eridani was included in the star catalogue of Johannes Hevelius. Its sequence number in constellation Eridanus was 14, its designation was Tertia (Latin for 'the third'), and it was assigned magnitude 3 or 4 (sources differ).[36][43] The star catalogue of English astronomer John Flamsteed, published in 1712, gave Epsilon Eridani the Flamsteed designation of 18 Eridani, because it was the eighteenth catalogued star in the constellation of Eridanus by order of increasing right ascension.[4] In 1818 Epsilon Eridani was included in Friedrich Bessel's catalogue, based on James Bradley's observations from 1750–1762, and at magnitude 4.[44] It also appeared in Nicolas Louis de Lacaille's catalogue of 398 principal stars, whose 307-star version was published in 1755 in the Ephémérides des Mouvemens Célestes, pour dix années, 1755–1765,[45] and whose full version was published in 1757 in Astronomiæ Fundamenta, Paris.[46] In its 1831 edition by Francis Baily, Epsilon Eridani has the number 50.[47] Lacaille assigned it magnitude 3.[45][46][47]

In 1801 Epsilon Eridani was included in Histoire céleste française, Joseph Jérôme Lefrançois de Lalande's catalogue of about 50,000 stars, based on his observations of 1791–1800, in which observations are arranged in time order. It contains three observations of Epsilon Eridani.[note 3][48] In 1847, a new edition of Lalande's catalogue was published by Francis Baily, containing the majority of its observations, in which the stars were numbered in order of right ascension. Because every observation of each star was numbered and Epsilon Eridani was observed three times, it got three numbers: 6581, 6582 and 6583.[49] (Today numbers from this catalogue are used with the prefix "Lalande", or "Lal".[50]) Lalande assigned Epsilon Eridani magnitude 3.[48][49] Also in 1801 it was included in the catalogue of Johann Bode, in which about 17,000 stars were grouped into 102 constellations and numbered (Epsilon Eridani got the number 159 in the constellation Eridanus). Bode's catalogue was based on observations of various astronomers, including Bode himself, but mostly on Lalande's and Lacaille's (for the southern sky). Bode assigned Epsilon Eridani magnitude 3.[51] In 1814 Giuseppe Piazzi published the second edition of his star catalogue (its first edition was published in 1803), based on observations during 1792–1813, in which more than 7000 stars were grouped into 24 hours (0–23). Epsilon Eridani is number 89 in hour 3. Piazzi assigned it magnitude 4.[52] In 1918 Epsilon Eridani appeared in the Henry Draper Catalogue with the designation HD 22049 and a preliminary spectral classification of K0.[53]

Detection of proximity

[edit]Based on observations between 1800 and 1880, Epsilon Eridani was found to have a large proper motion across the celestial sphere, which was estimated at three arcseconds per year (angular velocity).[54] This movement implied it was relatively close to the Sun,[55] making it a star of interest for the purpose of stellar parallax measurements. This process involves recording the position of Epsilon Eridani as Earth moves around the Sun, which allows a star's distance to be estimated.[54] From 1881 to 1883, American astronomer William L. Elkin used a heliometer at the Royal Observatory at the Cape of Good Hope, South Africa, to compare the position of Epsilon Eridani with two nearby stars. From these observations, a parallax of 0.14 ± 0.02 arcseconds was calculated.[56][57] By 1917, observers had refined their parallax estimate to 0.317 arcseconds.[58] The modern value of 0.3109 arcseconds is equivalent to a distance of about 10.50 light-years (3.22 pc).[1]

Circumstellar discoveries

[edit]

Based on apparent changes in the position of Epsilon Eridani between 1938 and 1972, Peter van de Kamp proposed that an unseen companion with an orbital period of 25 years was causing gravitational perturbations in its position.[59] This claim was refuted in 1993 by Wulff-Dieter Heintz and the false detection was blamed on a systematic error in the photographic plates.[60]

Launched in 1983, the space telescope IRAS detected infrared emissions from stars near to the Sun,[61] including an excess infrared emission from Epsilon Eridani.[62] The observations indicated a disk of fine-grained cosmic dust was orbiting the star;[62] this debris disk has since been extensively studied. Evidence for a planetary system was discovered in 1998 by the observation of asymmetries in this dust ring. The clumping in the dust distribution could be explained by gravitational interactions with a planet orbiting just inside the dust ring.[63]

In 1987, the detection of an orbiting planetary object was announced by Bruce Campbell, Gordon Walker and Stephenson Yang.[64][65] From 1980 to 2000, a team of astronomers led by Artie P. Hatzes made radial velocity observations of Epsilon Eridani, measuring the Doppler shift of the star along the line of sight. They found evidence of a planet orbiting the star with a period of about seven years.[20] Although there is a high level of noise in the radial velocity data due to magnetic activity in its photosphere,[66] any periodicity caused by this magnetic activity is expected to show a strong correlation with variations in emission lines of ionized calcium (the Ca II H and K lines). Because no such correlation was found, a planetary companion was deemed the most likely cause.[67] This discovery was supported by astrometric measurements of Epsilon Eridani made between 2001 and 2003 with the Hubble Space Telescope, which showed evidence for gravitational perturbation of Epsilon Eridani by a planet.[8]

SETI and proposed exploration

[edit]In 1960, physicists Philip Morrison and Giuseppe Cocconi proposed that extraterrestrial civilisations might be using radio signals for communication.[68] Project Ozma, led by astronomer Frank Drake, used the Tatel Telescope to search for such signals from the nearby Sun-like stars Epsilon Eridani and Tau Ceti. The systems were observed at the emission frequency of neutral hydrogen, 1,420 MHz (21 cm). No signals of intelligent extraterrestrial origin were detected.[69] Drake repeated the experiment in 2010, with the same negative result.[68] Despite this lack of success, Epsilon Eridani made its way into science fiction literature and television shows for many years following news of Drake's initial experiment.[70]

In Habitable Planets for Man, a 1964 RAND Corporation study by space scientist Stephen H. Dole, the probability of a habitable planet being in orbit around Epsilon Eridani were estimated at 3.3%. Among the known nearby stars, it was listed with the 14 stars that were thought most likely to have a habitable planet.[71]

William I. McLaughlin proposed a new strategy in the search for extraterrestrial intelligence (SETI) in 1977. He suggested that widely observable events such as nova explosions might be used by intelligent extraterrestrials to synchronise the transmission and reception of their signals. This idea was tested by the National Radio Astronomy Observatory in 1988, which used outbursts of Nova Cygni 1975 as the timer. Fifteen days of observation showed no anomalous radio signals coming from Epsilon Eridani.[72]

Because of the proximity and Sun-like properties of Epsilon Eridani, in 1985 physicist and author Robert L. Forward considered the system as a plausible target for interstellar travel.[73] The following year, the British Interplanetary Society suggested Epsilon Eridani as one of the targets in its Project Daedalus study.[74] The system has continued to be among the targets of such proposals, such as Project Icarus in 2011.[26]

Based on its nearby location, Epsilon Eridani was among the target stars for Project Phoenix, a 1995 microwave survey for signals from extraterrestrial intelligence.[75] The project had checked about 800 stars by 2004 but had not yet detected any signals.[76]

Properties

[edit]

At a distance of 10.50 ly (3.22 parsecs), Epsilon Eridani is the 13th-nearest known star (and ninth nearest solitary star or stellar system) to the Sun as of 2014.[9] Its proximity makes it one of the most studied stars of its spectral type.[77] Epsilon Eridani is located in the northern part of the constellation Eridanus, about 3° east of the slightly brighter star Delta Eridani. With a declination of −9.46°, Epsilon Eridani can be viewed from much of Earth's surface, at suitable times of year. Only to the north of latitude 80° N is it permanently hidden below the horizon.[78] The apparent magnitude of 3.73 can make it difficult to observe from an urban area with the unaided eye, because the night skies over cities are obscured by light pollution.[79]

Epsilon Eridani has an estimated mass of 0.82 solar masses[10][11] and a radius of 0.738 solar radii.[12] It shines with a luminosity of only 0.34 solar luminosities.[80] The estimated effective temperature is 5,084 K.[81] With a stellar classification of K2 V, it is the second-nearest K-type main-sequence star (after Alpha Centauri B).[9] Since 1943 the spectrum of Epsilon Eridani has served as one of the stable anchor points by which other stars are classified.[82] Its metallicity, the fraction of elements heavier than helium, is slightly lower than the Sun's.[83] In Epsilon Eridani's chromosphere, a region of the outer atmosphere just above the light emitting photosphere, the abundance of iron is estimated at 74% of the Sun's value.[83] The proportion of lithium in the atmosphere is five times less than that in the Sun.[84]

Epsilon Eridani's K-type classification indicates that the spectrum has relatively weak absorption lines from absorption by hydrogen (Balmer lines) but strong lines of neutral atoms and singly ionized calcium (Ca II). The luminosity class V (dwarf) is assigned to stars that are undergoing thermonuclear fusion of hydrogen in their core. For a K-type main-sequence star, this fusion is dominated by the proton–proton chain reaction, in which a series of reactions effectively combines four hydrogen nuclei to form a helium nucleus. The energy released by fusion is transported outward from the core through radiation, which results in no net motion of the surrounding plasma. Outside of this region, in the envelope, energy is carried to the photosphere by plasma convection, where it then radiates into space.[85]

Magnetic activity

[edit]Epsilon Eridani has a higher level of magnetic activity than the Sun, and thus the outer parts of its atmosphere (the chromosphere and corona) are more dynamic. The average magnetic field strength of Epsilon Eridani across the entire surface is (1.65±0.30)×10−2 tesla,[86] which is more than forty times greater than the (5–40) × 10−5 T magnetic-field strength in the Sun's photosphere.[87] The magnetic properties can be modelled by assuming that regions with a magnetic flux of about 0.14 T randomly cover approximately 9% of the photosphere, whereas the remainder of the surface is free of magnetic fields.[88] The overall magnetic activity of Epsilon Eridani shows co-existing 2.95±0.03 and 12.7±0.3 year activity cycles.[84] Assuming that its radius does not change over these intervals, the long-term variation in activity level appears to produce a temperature variation of 15 K, which corresponds to a variation in visual magnitude (V) of 0.014.[89]

The magnetic field on the surface of Epsilon Eridani causes variations in the hydrodynamic behaviour of the photosphere. This results in greater jitter during measurements of its radial velocity. Variations of 15 m s−1 were measured over a 20 year period, which is much higher than the measurement uncertainty of 3 m s−1. This makes interpretation of periodicities in the radial velocity of Epsilon Eridani, such as those caused by an orbiting planet, more difficult.[66]

Epsilon Eridani is classified as a BY Draconis variable because it has regions of higher magnetic activity that move into and out of the line of sight as it rotates.[6] Measurement of this rotational modulation suggests that its equatorial region rotates with an average period of 11.2 days,[15] which is less than half of the rotation period of the Sun. Observations have shown that Epsilon Eridani varies as much as 0.050 in V magnitude due to starspots and other short-term magnetic activity.[90] Photometry has also shown that the surface of Epsilon Eridani, like the Sun, is undergoing differential rotation i.e. the rotation period at equator differs from that at high latitude. The measured periods range from 10.8 to 12.3 days.[89][note 4] The axial tilt of Epsilon Eridani toward the line of sight from Earth is highly uncertain: estimates range from 24° to 72°.[15]

The high levels of chromospheric activity, strong magnetic field, and relatively fast rotation rate of Epsilon Eridani are characteristic of a young star.[91] Most estimates of the age of Epsilon Eridani place it in the range from 200 million to 800 million years.[18] The low abundance of heavy elements in the chromosphere of Epsilon Eridani usually indicates an older star, because the interstellar medium (out of which stars form) is steadily enriched by heavier elements produced by older generations of stars.[92] This anomaly might be caused by a diffusion process that has transported some of the heavier elements out of the photosphere and into a region below Epsilon Eridani's convection zone.[93]

The X-ray luminosity of Epsilon Eridani is about 2×1028 erg·s–1 (2×1021 W). It is more luminous in X-rays than the Sun at peak activity. The source for this strong X-ray emission is Epsilon Eridani's hot corona.[94][95] Epsilon Eridani's corona appears larger and hotter than the Sun's, with a temperature of 3.4×106 K, measured from observation of the corona's ultraviolet and X-ray emission.[96] It displays a cyclical variation in X-ray emission that is consistent with the magnetic activity cycle.[97]

The stellar wind emitted by Epsilon Eridani expands until it collides with the surrounding interstellar medium of diffuse gas and dust, resulting in a bubble of heated hydrogen gas (an astrosphere, the equivalent of the heliosphere that surrounds the Sun). The absorption spectrum from this gas has been measured with the Hubble Space Telescope, allowing the properties of the stellar wind to be estimated.[96] Epsilon Eridani's hot corona results in a mass loss rate in Epsilon Eridani's stellar wind that is 30 times higher than the Sun's. This stellar wind generates the astrosphere that spans about 8,000 au (0.039 pc) and contains a bow shock that lies 1,600 au (0.0078 pc) from Epsilon Eridani. At its estimated distance from Earth, this astrosphere spans 42 arcminutes, which is wider than the apparent size of the full Moon.[98]

Kinematics

[edit]Epsilon Eridani has a high proper motion, moving −0.976 arcseconds per year in right ascension (the celestial equivalent of longitude) and 0.018 arcseconds per year in declination (celestial latitude), for a combined total of 0.962 arcseconds per year.[1][note 5] The star has a radial velocity of +15.5 km/s (35,000 mph) (away from the Sun).[100] The space velocity components of Epsilon Eridani in the galactic co-ordinate system are (U, V, W) = (−3, +7, −20) km/s, which means that it is travelling within the Milky Way at a mean galactocentric distance of 28.7 kly (8.79 kiloparsecs) from the core along an orbit that has an eccentricity of 0.09.[101] The position and velocity of Epsilon Eridani indicate that it may be a member of the Ursa Major Moving Group, whose members share a common motion through space. This behaviour suggests that the moving group originated in an open cluster that has since diffused.[102] The estimated age of this group is 500±100 million years,[103] which lies within the range of the age estimates for Epsilon Eridani.

During the past million years, three stars are believed to have come within 7 ly (2.1 pc) of Epsilon Eridani. The most recent and closest of these encounters was with Kapteyn's Star, which approached to a distance of about 3 ly (0.92 pc) roughly 12,500 years ago. Two more distant encounters were with Sirius and Ross 614. None of these encounters are thought to have been close enough to affect the circumstellar disk orbiting Epsilon Eridani.[104]

Epsilon Eridani made its closest approach to the Sun about 105,000 years ago, when they were separated by 7 ly (2.1 pc).[105] Based upon a simulation of close encounters with nearby stars, the binary star system Luyten 726-8, which includes the variable star UV Ceti, will encounter Epsilon Eridani in approximately 31,500 years at a minimum distance of about 0.9 ly (0.29 parsecs). They will be less than 1 ly (0.3 parsecs) apart for about 4,600 years. If Epsilon Eridani has an Oort cloud, Luyten 726-8 could gravitationally perturb some of its comets with long orbital periods.[106][unreliable source?]

Planetary system

[edit]| Companion (in order from star) |

Mass | Semimajor axis (AU) |

Orbital period (days) |

Eccentricity | Inclination | Radius |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asteroid belt | ~1.5−2.0 (or 3–4) AU | — | — | |||

| b (AEgir)[109] | 0.76+0.14 −0.11 MJ |

3.53±0.06 | 2,688.60+16.17 −16.51 |

0.26±0.04 | 166.48+6.63 −6.66° |

— |

| Asteroid belt | ~8–20 AU | — | — | |||

| Main belt | 65–75 AU | 33.7° ± 0.5° | — | |||

Debris disc

[edit]

An infrared excess around Epsilon Eridani was detected by IRAS[62] indicating the presence of circumstellar dust. Observations with the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope (JCMT) at a wavelength of 850 μm show an extended flux of radiation out to an angular radius of 35 arcseconds around Epsilon Eridani, resolving the debris disc for the first time. Higher resolution images have since been taken with the Atacama Large Millimeter Array, showing that the belt is located 70 au from the star with a width of just 11 au.[110][24] The disc is inclined 33.7° from face-on, making it appear elliptical.

Dust and possibly water ice from this belt migrates inward because of drag from the stellar wind and a process by which stellar radiation causes dust grains to slowly spiral toward Epsilon Eridani, known as the Poynting–Robertson effect.[111] At the same time, these dust particles can be destroyed through mutual collisions. The time scale for all of the dust in the disk to be cleared away by these processes is less than Epsilon Eridani's estimated age. Hence, the current dust disk must have been created by collisions or other effects of larger parent bodies, and the disk represents a late stage in the planet-formation process. It would have required collisions between 11 Earth masses' worth of parent bodies to have maintained the disk in its current state over its estimated age.[107]

The disk contains an estimated mass of dust equal to a sixth of the mass of the Moon, with individual dust grains exceeding 3.5 μm in size at a temperature of about 55 K. This dust is being generated by the collision of comets, which range up to 10 to 30 km in diameter and have a combined mass of 5 to 9 times that of Earth. This is similar to the estimated 10 Earth masses in the primordial Kuiper belt.[112][113] The disk around Epsilon Eridani contains less than 2.2 × 1017 kg of carbon monoxide. This low level suggests a paucity of volatile-bearing comets and icy planetesimals compared to the Kuiper belt.[114]

The JCMT images show signs of clumpy structure in the belt that may be explained by gravitational perturbation from a planet, dubbed Epsilon Eridani c. The clumps in the dust are theorised to occur at orbits that have an integer resonance with the orbit of the suspected planet. For example, the region of the disk that completes two orbits for every three orbits of a planet is in a 3:2 orbital resonance.[115] The planet proposed to cause these perturbations is predicted to have a semimajor axis of between 40 and 50 au.[116][117][24] However, the brightest clumps have since been identified as background sources and the existence of the remaining clumps remains debated.[118]

Dust is also present closer to the star. Observations from NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope suggest that Epsilon Eridani actually has two asteroid belts and a cloud of exozodiacal dust. The latter is an analogue of the zodiacal dust that occupies the plane of the Solar System. One belt sits at approximately the same position as the one in the Solar System, orbiting at a distance of 3.00 ± 0.75 au from Epsilon Eridani, and consists of silicate grains with a diameter of 3 μm and a combined mass of about 1018 kg. If the planet Epsilon Eridani b exists then this belt is unlikely to have had a source outside the orbit of the planet, so the dust may have been created by fragmentation and cratering of larger bodies such as asteroids.[119] The second, denser belt, most likely also populated by asteroids, lies between the first belt and the outer comet disk. The structure of the belts and the dust disk suggests that more than two planets in the Epsilon Eridani system are needed to maintain this configuration.[107][120]

In an alternative scenario, the exozodiacal dust may be generated in the outer belt. This dust is then transported inward past the orbit of Epsilon Eridani b. When collisions between the dust grains are taken into account, the dust will reproduce the observed infrared spectrum and brightness. Outside the radius of ice sublimation, located beyond 10 au from Epsilon Eridani where the temperatures fall below 100 K, the best fit to the observations occurs when a mix of ice and silicate dust is assumed. Inside this radius, the dust must consist of silicate grains that lack volatiles.[111]

The inner region around Epsilon Eridani, from a radius of 2.5 AU inward, appears to be clear of dust down to the detection limit of the 6.5 m MMT telescope. Grains of dust in this region are efficiently removed by drag from the stellar wind, while the presence of a planetary system may also help keep this area clear of debris. Still, this does not preclude the possibility that an inner asteroid belt may be present with a combined mass no greater than the asteroid belt in the Solar System.[121]

Long-period planets

[edit]

As one of the nearest Sun-like stars, Epsilon Eridani has been the target of many attempts to search for planetary companions.[20][18] Its chromospheric activity and variability mean that finding planets with the radial velocity method is difficult, because the stellar activity may create signals that mimic the presence of planets.[122] Searches for exoplanets around Epsilon Eridani with direct imaging have been unsuccessful.[67][123]

Infrared observation has shown there are no bodies of three or more Jupiter masses in this system, out to at least a distance of 500 au from the host star.[18] Planets with similar masses and temperatures as Jupiter should be detectable by Spitzer at distances beyond 80 au. One roughly Jupiter-sized long-period planet has been detected and characterized by both the radial velocity and astrometry methods.[108] Planets more than 150% as massive as Jupiter can be ruled out at the inner edge of the debris disk at 30–35 au.[16]

Planet b (AEgir)

[edit]Referred to as Epsilon Eridani b, this planet was announced in 2000, but the discovery remained controversial over roughly the next two decades. A comprehensive study in 2008 called the detection "tentative" and described the proposed planet as "long suspected but still unconfirmed".[107] Many astronomers believed the evidence is sufficiently compelling that they regard the discovery as confirmed.[18][111][119][123] The discovery was questioned in 2013 because a search program at La Silla Observatory did not confirm it exists.[124] Further studies since 2018 have gradually reaffirmed the planet's existence through a combination of radial velocity and astrometry.[125][126][127][128][108]

Published sources remain in disagreement as to the planet's basic parameters. Recent values for its orbital period range from 7.3 to 7.6 years,[108] estimates of the size of its elliptical orbit—the semimajor axis—range from 3.38 au to 3.53 au,[129][130] and approximations of its orbital eccentricity range from 0.055 to 0.26.[108]

Initially, the planet's mass was unknown, but a lower limit could be estimated based on the orbital displacement of Epsilon Eridani. Only the component of the displacement along the line of sight to Earth was known, which yields a value for the formula m sin i, where m is the mass of the planet and i is the orbital inclination. Estimates for the value of m sin i ranged from 0.60 Jupiter masses to 1.06 Jupiter masses,[129][130] which sets the lower limit for the mass of the planet (because the sine function has a maximum value of 1). Taking m sin i in the middle of that range at 0.78, and estimating the inclination at 30° as was suggested by Hubble astrometry, this yields a value of 1.55 ± 0.24 Jupiter masses for the planet's mass.[8] More recent astrometric studies have found lower masses, ranging from 0.63 to 0.78 Jupiter masses.[108]

Of all the measured parameters for this planet, the value for orbital eccentricity is the most uncertain. The eccentricity of 0.7 suggested by some older studies[8] is inconsistent with the presence of the proposed asteroid belt at a distance of 3 au. If the eccentricity was this high, the planet would pass through the asteroid belt and clear it out within about ten thousand years. If the belt has existed for longer than this period, which appears likely, it imposes an upper limit on Epsilon Eridani b's eccentricity of about 0.10–0.15.[119][120] If the dust disk is instead being generated from the outer debris disk, rather than from collisions in an asteroid belt, then no constraints on the planet's orbital eccentricity are needed to explain the dust distribution.[111]

Potential habitability

[edit]Epsilon Eridani is a target for planet finding programs because it has properties that allow an Earth-like planet to form. Although this system was not chosen as a primary candidate for the now-canceled Terrestrial Planet Finder, it was a target star for NASA's proposed Space Interferometry Mission to search for Earth-sized planets.[131] The proximity, Sun-like properties and suspected planets of Epsilon Eridani have also made it the subject of multiple studies on whether an interstellar probe can be sent to Epsilon Eridani.[73][74][132]

The orbital radius at which the stellar flux from Epsilon Eridani matches the solar constant—where the emission matches the Sun's output at the orbital distance of the Earth—is 0.61 au.[133] That is within the maximum habitable zone of a conjectured Earth-like planet orbiting Epsilon Eridani, which currently stretches from about 0.5 to 1.0 au. As Epsilon Eridani ages over a period of 20 billion years, the net luminosity will increase, causing this zone to slowly expand outward to about 0.6–1.4 au.[134] The presence of a large planet with a highly elliptical orbit in proximity to Epsilon Eridani's habitable zone reduces the likelihood of a terrestrial planet having a stable orbit within the habitable zone.[135]

A young star such as Epsilon Eridani can produce large amounts of ultraviolet radiation that may be harmful to life, but on the other hand it is a cooler star than the Sun and so produces less ultraviolet radiation to start with.[21][136] The orbital radius where the UV flux matches that on the early Earth lies at just under 0.5 au.[21] Because that is actually slightly closer to the star than the habitable zone, this has led some researchers to conclude there is not enough energy from ultraviolet radiation reaching into the habitable zone for life to ever get started around the young Epsilon Eridani.[136]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ From Epsilon Eridani, the Sun would appear on the diametrically opposite side of the sky at the coordinates RA=15h 32m 55.84496s, Dec=+09° 27′ 29.7312″, which is located near Alpha Serpentis. The absolute magnitude of the Sun is 4.83,[a] so, at a distance of 3.212 parsecs, the Sun would have an apparent magnitude:

,[b] assuming negligible extinction (AV) for a nearby star.

Ref.:- Binney, James; Merrifield, Michael (1998), Galactic Astronomy, Princeton University Press, p. 56, ISBN 0-691-02565-7

- Karttunen, Hannu; et al. (2013), Fundamental Astronomy, Springer Science & Business Media, p. 103, ISBN 978-3-662-03215-2

- ^ This is because Bayer designated 21 stars in the northern part of Eridanus by preceding along the 'river' from east to west, starting from β (Supra pedem Orionis in flumine, prima, meaning above the foot of Orion in the river, the first) to the twenty-first, σ (Vigesima prima, that is the twenty-first). Epsilon Eridani was the seventeenth in this sequence. These 21 stars are: β, λ, ψ, b, ω, μ, c, ν, ξ, ο (two stars), d, A, γ, π, δ, ε, ζ, ρ, η, σ.[42]

- ^ 1796 September 17 (page 246), 1796 December 3 (page 248) and 1797 November 13 (page 307)

- ^ The rotation period Pβ at latitude β is given by:

- Pβ = Peq/(1 − k sin β)

- 0.03 ≤ k ≤ 0.10[15]

- ^ The total proper motion μ can be computed from:

- μ2 = (μα cos δ)2 + μδ2

- μ2 = (−975.17 · cos(−9.458°))2 + 19.492 = 925658.1

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f van Leeuwen, Floor (November 2007), "Validation of the new Hipparcos reduction", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 474 (2): 653–664, arXiv:0708.1752v1, Bibcode:2007A&A...474..653V, doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20078357, S2CID 18759600. Note: see VizieR catalogue I/311.

- ^ a b c Cousins, A. W. J. (1984), "Standardization of Broadband Photometry of Equatorial Standards", South African Astronomical Observatory Circulars, 8: 59, Bibcode:1984SAAOC...8...59C.

- ^ Gray, R. O.; et al. (July 2006), "Contributions to the Nearby Stars (NStars) Project: spectroscopy of stars earlier than M0 within 40 pc-The Southern Sample", The Astronomical Journal, 132 (1): 161–170, arXiv:astro-ph/0603770, Bibcode:2006AJ....132..161G, doi:10.1086/504637, S2CID 119476992.

- ^ a b c d e "V* eps Eri – variable of BY Dra type", SIMBAD, Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg, retrieved November 5, 2010.

- ^ a b c Cutri, R. M.; et al. (June 2003), "The IRSA 2MASS all-sky point source catalog, NASA/IPAC infrared science archive", The IRSA 2MASS All-Sky Point Source Catalog, Bibcode:2003tmc..book.....C.

- ^ a b "GCVS query=eps Eri", General Catalog of Variable Stars, Sternberg Astronomical Institute, Moscow, Russia, retrieved May 20, 2009.

- ^ Soubiran, C.; Jasniewicz, G.; Chemin, L.; Zurbach, C.; Brouillet, N.; Panuzzo, P.; Sartoretti, P.; Katz, D.; Le Campion, J.-F.; Marchal, O.; Hestroffer, D.; Thévenin, F.; Crifo, F.; Udry, S.; Cropper, M.; Seabroke, G.; Viala, Y.; Benson, K.; Blomme, R.; Jean-Antoine, A.; Huckle, H.; Smith, M.; Baker, S. G.; Damerdji, Y.; Dolding, C.; Frémat, Y.; Gosset, E.; Guerrier, A.; Guy, L. P.; Haigron, R.; Janßen, K.; Plum, G.; Fabre, C.; Lasne, Y.; Pailler, F.; Panem, C.; Riclet, F.; Royer, F.; Tauran, G.; Zwitter, T.; Gueguen, A.; Turon, C. (2018). "Gaia Data Release 2". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 616. EDP Sciences: A7. arXiv:1804.09370. Bibcode:2018A&A...616A...7S. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201832795. ISSN 0004-6361. S2CID 247759802.

- ^ a b c d Benedict, G. Fritz; et al. (November 2006), "The Extrasolar Planet ɛ Eridani b: Orbit and Mass", The Astronomical Journal, 132 (5): 2206–2218, arXiv:astro-ph/0610247, Bibcode:2006AJ....132.2206B, doi:10.1086/508323, S2CID 18603036.

- ^ a b c Staff (June 8, 2007), The one hundred nearest star systems, Research Consortium on Nearby Stars, retrieved November 29, 2007

- ^ a b Gonzalez, G.; Carlson, M. K.; Tobin, R. W. (April 2010), "Parent stars of extrasolar planets – X. Lithium abundances and v sini revisited", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 403 (3): 1368–1380, arXiv:0912.1621, Bibcode:2010MNRAS.403.1368G, doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2009.16195.x, S2CID 118520284. See table 3.

- ^ a b Baines, Ellyn K.; Armstrong, J. Thomas (2011), "Confirming Fundamental Parameters of the Exoplanet Host Star epsilon Eridani Using the Navy Optical Interferometer", The Astrophysical Journal, 748 (1): 72, arXiv:1112.0447, Bibcode:2012ApJ...748...72B, doi:10.1088/0004-637X/748/1/72, S2CID 124270967.

- ^ a b c d Rains, Adam D.; Ireland, Michael J.; White, Timothy R.; Casagrande, Luca; Karovicova, I. (April 1, 2020). "Precision angular diameters for 16 southern stars with VLTI/PIONIER". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 493 (2): 2377–2394. arXiv:2004.02343. Bibcode:2020MNRAS.493.2377R. doi:10.1093/mnras/staa282. ISSN 0035-8711.

- ^ a b Soubiran, C.; Creevey, O. L.; Lagarde, N.; Brouillet, N.; Jofré, P.; Casamiquela, L.; Heiter, U.; Aguilera-Gómez, C.; Vitali, S.; Worley, C.; de Brito Silva, D. (February 1, 2024). "Gaia FGK benchmark stars: Fundamental Teff and log g of the third version". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 682: A145. arXiv:2310.11302. Bibcode:2024A&A...682A.145S. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202347136. ISSN 0004-6361.

- ^ a b Roettenbacher, Rachael M.; Cabot, Samuel H. C.; Fischer, Debra A.; Monnier, John D.; Henry, Gregory W.; Harmon, Robert O.; Korhonen, Heidi; Brewer, John M.; Llama, Joe; Petersburg, Ryan R.; Zhao, Lily L.; Kraus, Stefan; Le Bouquin, Jean-Baptiste; Anugu, Narsireddy; Davies, Claire L.; Gardner, Tyler; Lanthermann, Cyprien; Schaefer, Gail; Setterholm, Benjamin; Clark, Catherine A.; Jorstad, Svetlana G.; Kuehn, Kyler; Levine, Stephen (January 2022), "EXPRES. III. Revealing the Stellar Activity Radial Velocity Signature of ϵ Eridani with Photometry and Interferometry", The Astronomical Journal, 163 (1): 19, arXiv:2110.10643, Bibcode:2022AJ....163...19R, doi:10.3847/1538-3881/ac3235, S2CID 239049996.

- ^ a b c d Fröhlich, H.-E. (December 2007), "The differential rotation of Epsilon Eri from MOST data", Astronomische Nachrichten, 328 (10): 1037–1039, arXiv:0711.0806, Bibcode:2007AN....328.1037F, doi:10.1002/asna.200710876, S2CID 11263751.

- ^ a b Janson, Markus; et al. (February 2015), "High-contrast imaging with Spitzer: deep observations of Vega, Fomalhaut, and ε Eridani", Astronomy & Astrophysics, 574: 10, arXiv:1412.4816, Bibcode:2015A&A...574A.120J, doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201424944, S2CID 118656652, A120.

- ^ a b "IAU Catalog of Star Names". Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e Janson, M.; et al. (September 2008), "A comprehensive examination of the ε Eridani system. Verification of a 4 micron narrow-band high-contrast imaging approach for planet searches", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 488 (2): 771–780, arXiv:0807.0301, Bibcode:2008A&A...488..771J, doi:10.1051/0004-6361:200809984, S2CID 119113471.

- ^ Di Folco, E.; et al. (November 2004), "VLTI near-IR interferometric observations of Vega-like stars. Radius and age of α PsA, β Leo, β Pic, ε Eri and τ Cet", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 426 (2): 601–617, Bibcode:2004A&A...426..601D, doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20047189.

- ^ a b c Hatzes, Artie P.; et al. (December 2000), "Evidence for a long-period planet orbiting ε Eridani", The Astrophysical Journal, 544 (2): L145 – L148, arXiv:astro-ph/0009423, Bibcode:2000ApJ...544L.145H, doi:10.1086/317319, S2CID 117865372.

- ^ a b c Buccino, A. P.; Mauas, P. J. D.; Lemarchand, G. A. (June 2003), R. Norris; F. Stootman (eds.), "UV Radiation in Different Stellar Systems", Bioastronomy 2002: Life Among the Stars, Proceedings of IAU Symposium No. 213, vol. 213, San Francisco: Astronomical Society of the Pacific, p. 97, Bibcode:2004IAUS..213...97B.

- ^ a b Final Results of NameExoWorlds Public Vote Released, International Astronomical Union, December 15, 2015, retrieved December 15, 2015.

- ^ a b Su, Kate Y. L.; et al. (2017), "The Inner 25 au Debris Distribution in the ϵ Eri System", The Astronomical Journal, 153 (5): 226, arXiv:1703.10330, Bibcode:2017AJ....153..226S, doi:10.3847/1538-3881/aa696b,

We found that the 24 and 35 μm emission is consistent with the in situ dust distribution produced either by one planetesimal belt at 3–21 au (e.g., Greaves et al. 2014) or by two planetesimal belts at 1.5–2 au (or 3–4 au) and 8–20 au (e.g., a slightly modified form of the proposal in Backman et al. 2009) ... Any planetesimal belt in the inner region of the epsilon Eri system must be located inside 2 au and/or outside 5 au to be dynamically stable with the assumed epsilon Eri b.

- ^ a b c d e Booth, Mark; Pearce, Tim D; Krivov, Alexander V; Wyatt, Mark C; Dent, William R F; Hales, Antonio S; Lestrade, Jean-François; Cruz-Sáenz de Miera, Fernando; Faramaz, Virginie C; Löhne, Torsten; Chavez-Dagostino, Miguel (March 30, 2023). "The clumpy structure of ϵ Eridani's debris disc revisited by ALMA". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 521 (4). Oxford University Press (OUP): 6180–6194. arXiv:2303.13584. Bibcode:2023MNRAS.521.6180B. doi:10.1093/mnras/stad938. ISSN 0035-8711.

- ^ Villard, Ray (December 2007), "Does life exist on this exoplanet?", Astronomy, 35 (12): 44–47, Bibcode:2007Ast....35l..44V.

- ^ a b Long, K. F.; Obousy, R. K.; Hein, A. (January 25, 2011), "Project Icarus: Optimisation of nuclear fusion propulsion for interstellar missions", Acta Astronautica, 68 (11–12): 1820–1829, Bibcode:2011AcAau..68.1820L, doi:10.1016/j.actaastro.2011.01.010.

- ^ NameExoWorlds: An IAU Worldwide Contest to Name Exoplanets and their Host Stars, International Astronomical Union, July 9, 2014, retrieved September 5, 2015.

- ^ "The Exoworlds", NameExoWorlds, International Astronomical Union, archived from the original on December 31, 2016, retrieved September 5, 2015.

- ^ "The Process", NameExoWorlds, International Astronomical Union, August 7, 2015, archived from the original on August 15, 2015, retrieved September 5, 2015.

- ^ NameExoWorlds The Approved Names, archived from the original on February 1, 2018, retrieved September 7, 2016.

- ^ "IAU Working Group on Star Names (WGSN)". Retrieved May 22, 2016.

- ^ "Bulletin of the IAU Working Group on Star Names, No. 1" (PDF). Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ^ "Object query for 'HD 22049'", Astrophysics Data System, retrieved March 15, 2023.

- ^ (in Chinese) 中國星座神話, written by 陳久金. Published by 台灣書房出版有限公司, 2005, ISBN 978-986-7332-25-7.

- ^ (in Chinese) 香港太空館 – 研究資源 – 亮星中英對照表 Archived August 19, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, Hong Kong Space Museum. Accessed on line November 23, 2010.

- ^ a b c d Baily, Francis (1843), "The Catalogues of Ptolemy, Ulugh Beigh, Tycho Brahe, Halley, Hevelius, Deduced from the Best Authorities. With Various Notes and Corrections, and a Preface to Each Catalogue. To Which is Added the Synonym of each Star, in the Catalogues of Flamsteed of Lacaille, as far as the same can be ascertained", Memoirs of the Royal Astronomical Society, 13: 1, Bibcode:1843MmRAS..13....1B. (Epsilon Eridani: for Ptolemy's catalogue see page 60, for Ulugh Beg's – page 109, for Tycho Brahe's – page 156, for Hevelius' – page 209).

- ^ a b Verbunt, F.; van Gent, R. H. (2012), "The star catalogues of Ptolemaios and Ulugh Beg. Machine-readable versions and comparison with the modern Hipparcos Catalogue", Astronomy & Astrophysics, 544: A31, arXiv:1206.0628, Bibcode:2012A&A...544A..31V, doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201219596, S2CID 54017245.

- ^ Звёздный каталог ал-Бируни с приложением каталогов Хайяма и ат-Туси. djvu Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. (Epsilon Eridani: see page 135).

- ^ Verbunt, F.; van Gent, R. H. (2010), "Three editions of the star catalogue of Tycho Brahe. Machine-readable versions and comparison with the modern Hipparcos Catalogue", Astronomy & Astrophysics, 516: A28, arXiv:1003.3836, Bibcode:2010A&A...516A..28V, doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201014002, S2CID 54025412.

- ^ Swerdlow, N. M. (August 1986), "A star catalogue used by Johannes Bayer", Journal for the History of Astronomy, 17 (50): 189–197, Bibcode:1986JHA....17..189S, doi:10.1177/002182868601700304, S2CID 118829690. See p. 192.

- ^ Hoffleit, D.; Warren Jr., W. H. (1991), Bright star catalogue (5th ed.), Yale University Observatory, retrieved July 5, 2010.

- ^ a b Bayer, Johann (1603). "Uranometria: omnium asterismorum continens schemata, nova methodo delineata, aereis laminis expressa". Uranometria in Linda Hall Library: link Archived July 24, 2018, at the Wayback Machine. Pages on constellation Eridanus: Table[permanent dead link], Map Archived September 17, 2020, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Verbunt, F.; van Gent, R. H. (2010), "The star catalogue of Hevelius. Machine-readable version and comparison with the modern Hipparcos Catalogue", Astronomy & Astrophysics, 516: A29, arXiv:1003.3841, Bibcode:2010A&A...516A..29V, doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201014003.

- ^ Bessel, Friedrich Wilhelm (1818). "Fundamenta astronomiae pro anno MDCCLV deducta ex observationibus viri incomparabilis James Bradley in specula astronomica Grenovicensi per annos 1750–1762 institutis". Frid. Nicolovius. Google Books id: UHRYAAAAcAAJ. Page with Epsilon Eridani: 158.

- ^ a b Lacaille, Nicolas Louis de. (1755). "Ephemerides des mouvemens celestes, pour dix années, depuis 1755 jusqu'en 1765, et pour le meridien de la ville de Paris". Paris. Google Books id: CGHtdxdcc5UC. (Epsilon Eridani: see page LV of the "Introduction").

- ^ a b Lacaille, Nicolas Louis de. (1757). "Astronomiæ fundamenta". Paris. Google Books id: -VQ_AAAAcAAJ. (Epsilon Eridani: see page 233 (in the catalogue), see also pages 96, 153–154, 189, 231).

- ^ a b Baily, Francis (1831), "On Lacaille's catalogue of 398 stars", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 2 (5): 33–34, Bibcode:1831MNRAS...2...33B, doi:10.1093/mnras/2.5.33. (Epsilon Eridani: see page 110).

- ^ a b Lalande, Joseph Jérôme Le Français de (1801). "Histoire céleste française". Paris, Imprimerie de la République. Google Books id: f9AMAAAAYAAJ. Pages with Epsilon Eridani: 246, 248, 307

- ^ a b Baily, Francis; Lalande, Joseph Jérôme Le Français de (1847). "Catalogue of those stars in the Histoire céleste française of Jérôme Delalande, for which tables of reduction to the epoch 1800 habe been published by Prof. Schumacher". London (1847). Bibcode:1847cshc.book.....B. Google Books id: oc0-AAAAcAAJ. Page with Epsilon Eridani: 165.

- ^ Dictionary of Nomenclature of Celestial Objects. Lal entry. SIMBAD. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg.

- ^ Bode, Johann Elert (1801). "Algemaine Beschreibung u. Nachweisung der gestine nebst Verzeichniss der gerarden Aufsteigung u. Abweichung von 17240 Sternen Doppelsternen Nobelflocken u. Sternhaufen". Berlin: Beym Verfasser. Bibcode:1801abun.book.....B. Google Books id: NUlRAAAAcAAJ. (List of observers and description of the catalogue: see page 32 of the "Introduction". List of constellations: see page 96). (Epsilon Eridani: see page 71).

- ^ Piazzi, Giuseppe. (1814). "Praecipuaram stellarum inerranthium positiones mediae ineunte saeculo 19. EX observationibus habilis in specula panormitana AB anno 1792 AD annum 1813". Palermo: Tip. Militare. Bibcode:1814psip.book.....P. Google Books id: c40RAAAAYAAJ. (Epsilon Eridani: see page 22).

- ^ Cannon, Annie J.; Pickering, Edward C. (1918), "The Henry Draper catalogue 0h, 1h, 2h, and 3h", Annals of Harvard College Observatory, 91: 1–290, Bibcode:1918AnHar..91....1C.—see p. 236

- ^ a b Gill, David; Elkin, W. L. (1884), Heliometer determinations of stellar parallaxes in the southern hemisphere, London, UK: The Royal Astronomical Society, pp. 174–180.

- ^ Belkora, Leila (2002), Minding the heavens: the story of our discovery of the Milky Way, London, U.K.: CRC Press, p. 151, ISBN 0-7503-0730-7.

- ^ Gill, David (1893), Heliometer observations for determination of stellar parallax, London: Eyre and Spottiswoode, p. xvi.

- ^ Gill, David (1884), "The fixed stars", Nature, 30 (763): 156–159, Bibcode:1884Natur..30..156., doi:10.1038/030156a0.

- ^ Adams, W. S.; Joy, A. H. (1917), "The luminosities and parallaxes of five hundred stars", The Astrophysical Journal, 46: 313–339, Bibcode:1917ApJ....46..313A, doi:10.1086/142369.

- ^ van de Kamp, P. (April 1974), "Parallax and orbital motion of Epsilon Eridani", The Astronomical Journal, 79: 491–492, Bibcode:1974AJ.....79..491V, doi:10.1086/111571.

- ^ Heintz, W. D. (March 1992), "Photographic astrometry of binary and proper-motion stars. VII", The Astronomical Journal, 105 (3): 1188–1195, Bibcode:1993AJ....105.1188H, doi:10.1086/116503. See the note for BD −9°697 on page 1192.

- ^ Neugebauer, G.; et al. (March 1984), "The Infrared Astronomical Satellite (IRAS) mission", The Astrophysical Journal, 278: L1 – L6, Bibcode:1984ApJ...278L...1N, doi:10.1086/184209, hdl:1887/6453.

- ^ a b c Aumann, H. H. (October 1985), "IRAS observations of matter around nearby stars", Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, 97: 885–891, Bibcode:1985PASP...97..885A, doi:10.1086/131620, S2CID 121192947.

- ^ Greaves, J. S.; et al. (October 1998), "A dust ring around Epsilon Eridani: analog to the young Solar System", The Astrophysical Journal, 506 (2): L133 – L137, arXiv:astro-ph/9808224, Bibcode:1998ApJ...506L.133G, doi:10.1086/311652, S2CID 15114295.

- ^ James E., Hesser (December 1987), "Dominion Astrophysical Observatory, Victoria, British Columbia", Quarterly Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society, 28: 510, Bibcode:1987QJRAS..28..510..

- ^ Campbell, Bruce; Walker, G. A. H.; Yang, S. (August 15, 1988), "A search for substellar companions to solar-type stars", Astrophysical Journal, Part 1, 331: 902–921, Bibcode:1988ApJ...331..902C, doi:10.1086/166608.

- ^ a b Marcy, Geoffrey W.; et al. (August 7–11, 2000), A. Penny (ed.), "Planetary Messages in the Doppler Residuals (Invited Review)", Planetary Systems in the Universe, Proceedings of IAU Symposium No. 202, vol. 202, Manchester, United Kingdom, pp. 20–28, Bibcode:2004IAUS..202...20M.

- ^ a b Janson, Markus; et al. (June 2007), "NACO-SDI Direct Imaging Search for the Exoplanet ε Eri b", The Astronomical Journal, 133 (6): 2442–2456, arXiv:astro-ph/0703300, Bibcode:2007AJ....133.2442J, doi:10.1086/516632, S2CID 56043012.

- ^ a b Gugliucci, Nicole (May 24, 2010), "Frank Drake returns to search for extraterrestrial life", Discovery News, Discovery Communications, LLC, archived from the original on February 3, 2012, retrieved July 5, 2010.

- ^ Heidmann, Jean; Dunlop, Storm (1995), Extraterrestrial intelligence, Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, p. 113, ISBN 0-521-58563-5.

- ^ Marschall, Laurence A.; Maran, Stephen P. (2009), Pluto confidential: an insider account of the ongoing battles over the status of Pluto, BenBella Books, p. 171, ISBN 978-1-933771-80-9.

- ^ Dole, Stephen H. (1964), Habitable planets for man (1st ed.), New York, N.Y.: Blaisdell Publishing Company, pp. 110 & 113, ISBN 0-444-00092-5, retrieved July 22, 2008.

- ^ Forbes, M. A.; Westpfahl, D. J. (September 1988), "A test of McLaughlin's strategy for timing SETI experiments", Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society, 20: 1043, Bibcode:1988BAAS...20.1043F.

- ^ a b Forward, R. L. (May–June 1985), "Starwisp – an ultra-light interstellar probe", Journal of Spacecraft and Rockets, 22 (3): 345–350, Bibcode:1985JSpRo..22..345F, doi:10.2514/3.25754, S2CID 54692367.

- ^ a b Martin, A. R. (February 1976), "Project Daedalus – The ranking of nearby stellar systems for exploration", Journal of the British Interplanetary Society, 29: 94–100, Bibcode:1976JBIS...29...94M.

- ^ Henry, T.; et al. (August 16–20, 1993), "The current state of target selection for NASA's high resolution microwave survey", Progress in the Search for Extraterrestrial Life, Astronomical Society of the Pacific Conference Series, vol. 74, Santa Cruz, California: Astronomical Society of the Pacific, pp. 207–218, Bibcode:1995ASPC...74..207H.

- ^ Whitehouse, David (March 25, 2004), "Radio search for ET draws a blank", BBC News, retrieved July 22, 2008.

- ^ Vieytes, Mariela C.; Mauas, Pablo J. D.; Díaz, Rodrigo F. (September 2009), "Chromospheric changes in K stars with activity", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 398 (3): 1495–1504, arXiv:0906.1760, Bibcode:2009MNRAS.398.1495V, doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2009.15207.x, S2CID 17768058.

- ^ Campbell, William Wallace (1899), The elements of practical astronomy, New York, N.Y.: The MacMillan Company, pp. 109–110.

- ^ Narisada, Kohei; Schreuder, Duco (2004), Light Pollution Handbook, Astrophysics and Space Science Library, vol. 322, Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer, pp. 118–132, Bibcode:2004ASSL..322.....N, doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-2666-9, ISBN 1-4020-2665-X.

- ^ Saumon, D.; et al. (April 1996), "A theory of extrasolar giant planets", The Astrophysical Journal, 460: 993–1018, arXiv:astro-ph/9510046, Bibcode:1996ApJ...460..993S, doi:10.1086/177027, S2CID 18116542.

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) See Table A1, p. 21. - ^ Kovtyukh, V. V.; et al. (December 2003), "High precision effective temperatures for 181 F-K dwarfs from line-depth ratios", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 411 (3): 559–564, arXiv:astro-ph/0308429, Bibcode:2003A&A...411..559K, doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20031378, S2CID 18478960.

- ^ Garrison, R. F. (December 1993), "Anchor Points for the MK System of Spectral Classification", Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society, 25: 1319, Bibcode:1993AAS...183.1710G, archived from the original on June 25, 2019, retrieved February 4, 2012.

- ^ a b Santos, N. C.; Israelian, G.; Mayor, M. (March 2004), "Spectroscopic [Fe/H] for 98 extra-solar planet-host stars: Exploring the probability of planet formation", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 415 (3): 1153–1166, arXiv:astro-ph/0311541, Bibcode:2004A&A...415.1153S, doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20034469, S2CID 11800380.—the percentage of iron is given by , or 74%

- ^ a b Metcalfe, T. S.; et al. (2016), "Magnetic Activity Cycles in the Exoplanet Host Star epsilon Eridani", The Astrophysical Journal Letters, 763 (2): 6, arXiv:1604.06701, Bibcode:2013ApJ...763L..26M, doi:10.1088/2041-8205/763/2/L26, S2CID 119163275, L26.

- ^ Karttunen, Hannu; Oja, H. (2007), Fundamental astronomy (5th ed.), Heidelberg, Germany: Springer, pp. 209–213, 247–249, ISBN 978-3-540-34143-7.

- ^ Rüedi, I.; Solanki, S. K.; Mathys, G.; Saar, S. H. (February 1997), "Magnetic field measurements on moderately active cool dwarfs", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 318: 429–442, Bibcode:1997A&A...318..429R.

- ^ Wang, Y.-M.; Sheeley, N. R. Jr. (July 2003), "Modeling the Sun's Large-Scale Magnetic Field during the Maunder Minimum", The Astrophysical Journal, 591 (2): 1248–1256, Bibcode:2003ApJ...591.1248W, doi:10.1086/375449.

- ^ Valenti, Jeff A.; Marcy, Geoffrey W.; Basri, Gibor (February 1995), "Infrared zeeman analysis of Epsilon Eridani", The Astrophysical Journal, 439 (2): 939–956, Bibcode:1995ApJ...439..939V, doi:10.1086/175231.

- ^ a b Gray, David F.; Baliunas, Sallie L. (March 1995), "Magnetic activity variations of Epsilon Eridani", The Astrophysical Journal, 441 (1): 436–442, Bibcode:1995ApJ...441..436G, doi:10.1086/175368.

- ^ a b Frey, Gary J.; et al. (November 1991), "The rotation period of Epsilon Eri from photometry of its starspots", The Astrophysical Journal, 102 (5): 1813–1815, Bibcode:1991AJ....102.1813F, doi:10.1086/116005.

- ^ Drake, Jeremy J.; Smith, Geoffrey (August 1993), "The fundamental parameters of the chromospherically active K2 dwarf Epsilon Eridani", The Astrophysical Journal, 412 (2): 797–809, Bibcode:1993ApJ...412..797D, doi:10.1086/172962.

- ^ Rocha-Pinto, H. J.; et al. (June 2000), "Chemical enrichment and star formation in the Milky Way disk. I. Sample description and chromospheric age-metallicity relation", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 358: 850–868, arXiv:astro-ph/0001382, Bibcode:2000A&A...358..850R.

- ^ Gai, Ning; Bi, Shao-Lan; Tang, Yan-Ke (October 2008), "Modeling ε Eri and asteroseismic tests of element diffusion", Chinese Journal of Astronomy and Astrophysics, 8 (5): 591–602, arXiv:0806.1811, Bibcode:2008ChJAA...8..591G, doi:10.1088/1009-9271/8/5/10, S2CID 16642862.

- ^ Johnson, H. M. (January 1, 1981), "An X-ray sampling of nearby stars", Astrophysical Journal, Part 1, 243: 234–243, Bibcode:1981ApJ...243..234J, doi:10.1086/158589.

- ^ Schmitt, J. H. M. M.; et al. (February 1996), "The extreme-ultraviolet spectrum of the nearby K Dwarf ε Eridani", Astrophysical Journal, 457: 882, Bibcode:1996ApJ...457..882S, doi:10.1086/176783.

- ^ a b Ness, J.-U.; Jordan, C. (April 2008), "The corona and upper transition region of ε Eridani", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 385 (4): 1691–1708, arXiv:0711.3805, Bibcode:2008MNRAS.385.1691N, doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2007.12757.x, S2CID 17396544.

- ^ Coffaro, M.; et al. (April 2020), "An X-ray activity cycle on the young solar-like star ɛ Eridani", Astronomy & Astrophysics, 636: 18, arXiv:2002.11009, Bibcode:2020A&A...636A..49C, doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201936479, S2CID 211296501, A49.

- ^ Wood, Brian E.; Müller, Hans-Reinhard; Zank, Gary P.; Linsky, Jeffrey L. (July 2002), "Measured mass-loss rates of solar-like stars as a function of age and activity", The Astrophysical Journal, 574 (1): 412–425, arXiv:astro-ph/0203437, Bibcode:2002ApJ...574..412W, doi:10.1086/340797, S2CID 1500425. See p. 10.

- ^ Birney, D. Scott; González, Guillermo; Oesper, David (2006), Observational astronomy (2nd ed.), Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, p. 75, ISBN 0-521-85370-2.

- ^ Evans, D. S. (June 20–24, 1966), Batten, Alan Henry; Heard, John Frederick (eds.), "The revision of the general catalogue of radial velocities", Determination of Radial Velocities and their Applications, Proceedings from IAU Symposium no. 30, vol. 30, University of Toronto: International Astronomical Union, p. 57, Bibcode:1967IAUS...30...57E.

- ^ de Mello, G. F. Porto; del Peloso, E. F.; Ghezzi, Luan (2006), "Astrobiologically interesting stars within 10 parsecs of the Sun", Astrobiology, 6 (2): 308–331, arXiv:astro-ph/0511180, Bibcode:2006AsBio...6..308P, doi:10.1089/ast.2006.6.308, PMID 16689649, S2CID 119459291.

- ^ Fuhrmann, K. (January 2004), "Nearby stars of the Galactic disk and halo. III", Astronomische Nachrichten, 325 (1): 3–80, Bibcode:2004AN....325....3F, doi:10.1002/asna.200310173.

- ^ King, Jeremy R.; et al. (April 2003), "Stellar kinematic groups. II. A reexamination of the membership, activity, and age of the Ursa Major group", The Astronomical Journal, 125 (4): 1980–2017, Bibcode:2003AJ....125.1980K, doi:10.1086/368241.

- ^ Deltorn, J.-M.; Greene, P. (May 16, 2001), "Search for nemesis encounters with Vega, epsilon Eridani, and Fomalhaut", in Jayawardhana, Ray; Greene, Thoas (eds.), Young Stars Near Earth: Progress and Prospects, Astronomical Society of the Pacific Conference Series, vol. 244, San Francisco, CA: Astronomical Society of the Pacific, pp. 227–232, arXiv:astro-ph/0105284, Bibcode:2001ASPC..244..227D, ISBN 1-58381-082-X.

- ^ García-Sánchez, J.; et al. (November 2001), "Stellar encounters with the Solar System", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 379 (2): 634–659, Bibcode:2001A&A...379..634G, doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20011330.

- ^ Potemine, Igor Yu. (April 12, 2010). "Transit of Luyten 726-8 within 1 ly from Epsilon Eridani". arXiv:1004.1557 [astro-ph.SR].

- ^ a b c d Backman, D.; et al. (2009), "Epsilon Eridani's planetary debris disk: structure and dynamics based on Spitzer and CSO observations", The Astrophysical Journal, 690 (2): 1522–1538, arXiv:0810.4564, Bibcode:2009ApJ...690.1522B, doi:10.1088/0004-637X/690/2/1522, S2CID 18183427.

- ^ a b c d e f Feng, Fabo; Butler, R. Paul; et al. (July 2023). "Revised orbits of the two nearest Jupiters". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 525 (1): 607–619. arXiv:2307.13622. Bibcode:2023MNRAS.525..607F. doi:10.1093/mnras/stad2297.

- ^ Naming of exoplanets, International Astronomical Union, retrieved August 20, 2021.

- ^ Booth, Mark; Dent, William R. F.; Jordán, Andrés; Lestrade, Jean-François; Hales, Antonio S.; Wyatt, Mark C.; Casassus, Simon; Ertel, Steve; Greaves, Jane S.; Kennedy, Grant M.; Matrà, Luca; Augereau, Jean-Charles; Villard, Eric (May 4, 2017). "The Northern arc of ε Eridani's Debris Ring as seen by ALMA". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 469 (3). Oxford University Press (OUP): 3200–3212. doi:10.1093/mnras/stx1072. hdl:10150/625481. ISSN 0035-8711.

- ^ a b c d Reidemeister, M.; et al. (March 2011), "The cold origin of the warm dust around ε Eridani", Astronomy & Astrophysics, 527: A57, arXiv:1011.4882, Bibcode:2011A&A...527A..57R, doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201015328, S2CID 56019152.

- ^ Davis, G. R.; et al. (February 2005), "Structure in the ε Eridani debris disk", The Astrophysical Journal, 619 (2): L187 – L190, arXiv:astro-ph/0208279, Bibcode:2005ApJ...619L.187G, doi:10.1086/428348, S2CID 121935302.

- ^ Morbidelli, A.; Brown, M. E.; Levison, H. F. (June 2003), "The Kuiper Belt and its primordial sculpting", Earth, Moon, and Planets, 92 (1): 1–27, Bibcode:2003EM&P...92....1M, doi:10.1023/B:MOON.0000031921.37380.80, S2CID 189905479.

- ^ Coulson, I. M.; Dent, W. R. F.; Greaves, J. S. (March 2004), "The absence of CO from the dust peak around ε Eri", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 348 (3): L39 – L42, Bibcode:2004MNRAS.348L..39C, doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2004.07563.x.

- ^ Ozernoy, Leonid M.; Gorkavyi, Nick N.; Mather, John C.; Taidakova, Tanya A. (July 2000), "Signatures of exosolar planets in dust debris disks", The Astrophysical Journal Letters, 537 (2): L147 – L151, arXiv:astro-ph/0007014, Bibcode:2000ApJ...537L.147O, doi:10.1086/312779, S2CID 1149097.

- ^ Quillen, A. C.; Thorndike, Stephen (October 2002), "Structure in the ε Eridani dusty disk caused by mean motion resonances with a 0.3 eccentricity planet at periastron", The Astrophysical Journal, 578 (2): L149 – L142, arXiv:astro-ph/0208279, Bibcode:2002ApJ...578L.149Q, doi:10.1086/344708, S2CID 955461.

- ^ Deller, A. T.; Maddison, S. T. (May 20, 2005). "Numerical Modeling of Dusty Debris Disks". The Astrophysical Journal. 625 (1). American Astronomical Society: 398–413. arXiv:astro-ph/0502135. Bibcode:2005ApJ...625..398D. doi:10.1086/429365. ISSN 0004-637X. S2CID 2764643.

- ^ Chavez-Dagostino, M.; Bertone, E.; Cruz-Saenz de Miera, F.; Marshall, J. P.; Wilson, G. W.; Sánchez-Argüelles, D.; Hughes, D. H.; Kennedy, G.; Vega, O.; De la Luz, V.; Dent, W. R. F.; Eiroa, C.; Gómez-Ruiz, A. I.; Greaves, J. S.; Lizano, S.; López-Valdivia, R.; Mamajek, E.; Montaña, A.; Olmedo, M.; Rodríguez-Montoya, I.; Schloerb, F. P.; Yun, Min S.; Zavala, J. A.; Zeballos, M. (June 8, 2016). "Early science with the Large Millimetre Telescope: Deep LMT/AzTEC millimetre observations of ϵ Eridani and its surroundings". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 462 (3). Oxford University Press (OUP): 2285–2294. arXiv:1606.02761. doi:10.1093/mnras/stw1363. ISSN 0035-8711.

- ^ a b c Brogi, M.; Marzari, F.; Paolicchi, P. (May 2009), "Dynamical stability of the inner belt around Epsilon Eridani", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 499 (2): L13 – L16, Bibcode:2009A&A...499L..13B, doi:10.1051/0004-6361/200811609.

- ^ a b Clavin, Whitney (October 27, 2008), "Closest planetary system hosts two asteroid belts", NASA/JPL-Caltech, archived from the original on November 19, 2012, retrieved July 4, 2010.

- ^ Liu, Wilson M.; et al. (March 2009), "Observations of Main-Sequence Stars and Limits on Exozodical Dust with Nulling Interferometry", The Astrophysical Journal, 693 (2): 1500–1507, Bibcode:2009ApJ...693.1500L, doi:10.1088/0004-637X/693/2/1500.

- ^ Setiawan, J.; et al. (2008), "Planets Around Active Stars", in Santos, N.C.; Pasquini, L.; Correia, A.; Romaniello, M (eds.), Precision Spectroscopy in Astrophysics, ESO Astrophysics Symposia, Garching, Germany: European Southern Observatory, pp. 201–204, arXiv:0704.2145, Bibcode:2008psa..conf..201S, doi:10.1007/978-3-540-75485-5_43, ISBN 978-3-540-75484-8, S2CID 116889047.

- ^ a b Heinze, A. N.; et al. (November 2008), "Deep L'- and M-band imaging for planets around Vega and ε Eridani", The Astrophysical Journal, 688 (1): 583–596, arXiv:0807.3975, Bibcode:2008ApJ...688..583H, doi:10.1086/592100, S2CID 17082115.

- ^ Zechmeister, M.; et al. (April 2013), "The planet search programme at the ESO Coudé Echelle spectrometer and HARPS. IV. The search for Jupiter analogues around solar-like stars", Astronomy & Astrophysics, 552: 62, arXiv:1211.7263, Bibcode:2013A&A...552A..78Z, doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201116551, S2CID 53694238, A78.

- ^ Mawet, Dimitri; Hirsch, Lea; et al. (2019), "Deep Exploration of ϵ Eridani with Keck Ms-band Vortex Coronagraphy and Radial Velocities: Mass and Orbital Parameters of the Giant Exoplanet" (PDF), The Astronomical Journal, 157 (1): 33, arXiv:1810.03794, Bibcode:2019AJ....157...33M, doi:10.3847/1538-3881/aaef8a, ISSN 1538-3881, OCLC 7964711337, S2CID 119350738,

In this paper, we have presented the most sensitive and comprehensive observational evidence for the existence of ε Eridani b.

- ^ Makarov, Valeri V.; Zacharias, Norbert; Finch, Charles T. (2021), "Looking for Astrometric Signals below 20 m s−1: A Jupiter-mass Planet Signature in ε Eri", Research Notes of the AAS, 5 (6): 155, arXiv:2107.01090, Bibcode:2021RNAAS...5..155M, doi:10.3847/2515-5172/ac0f59,

We conclude that the newest astrometric results confirm the existence of a long-period exoplanet orbiting ε Eri....The results are consistent with the previously reported planet epsEri-b of approximately Jupiter mass and a period of several years.

- ^ Llop-Sayson, Jorge; Wang, Jason J.; et al. (November 2021). "Constraining the Orbit and Mass of epsilon Eridani b with Radial Velocities, Hipparcos IAD-Gaia DR2 Astrometry, and Multiepoch Vortex Coronagraphy Upper Limits". The Astronomical Journal. 162 (5): 181. arXiv:2108.02305. Bibcode:2021AJ....162..181L. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/ac134a. 181.

- ^ Benedict, G. Fritz (March 2022). "Revisiting HST/FGS Astrometry of epsilon Eridani". Research Notes of the AAS. 6 (3): 45. Bibcode:2022RNAAS...6...45B. doi:10.3847/2515-5172/ac5b6b.

- ^ a b Wright, Jason; Marcy, Geoff (July 2010), Catalog of nearby exoplanets, California Planet Survey consortium, retrieved November 7, 2010.

- ^ a b Butler, R. P.; et al. (2006), "Catalog of nearby exoplanets", The Astrophysical Journal, 646 (1): 505–522, arXiv:astro-ph/0607493, Bibcode:2006ApJ...646..505B, doi:10.1086/504701, S2CID 119067572.

- ^ McCarthy, Chris (2008), Space Interferometry Mission: key science project, Exoplanets Group, San Francisco State University, archived from the original on August 10, 2007, retrieved July 22, 2008.

- ^ McNutt, R. L.; et al. (January 19, 2000), "A realistic interstellar explorer", AIP Conference Proceedings, 504: 917–924, Bibcode:2000AIPC..504..917M, doi:10.1063/1.1302595.

- ^ Kitzmann, D.; et al. (February 2010), "Clouds in the atmospheres of extrasolar planets. I. Climatic effects of multi-layered clouds for Earth-like planets and implications for habitable zones", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 511: 511A66.1–511A66.14, arXiv:1002.2927, Bibcode:2010A&A...511A..66K, doi:10.1051/0004-6361/200913491, S2CID 56345031. See table 3.

- ^ Underwood, David R.; Jones, Barrie W.; Sleep, P. Nick (2003), "The evolution of habitable zones during stellar lifetimes and its implications on the search for extraterrestrial life", International Journal of Astrobiology, 2 (4): 289–299, arXiv:astro-ph/0312522, Bibcode:2003IJAsB...2..289U, doi:10.1017/S1473550404001715, S2CID 119496186.

- ^ Jones, Barrie W.; Underwood, David R.; Sleep, P. Nick (April 22–25, 2003), "The stability of the orbits of Earth-mass planets in and near the habitable zones of known exoplanetary systems", Proceedings of the Conference on Towards Other Earths: DARWIN/TPF and the Search for Extrasolar Terrestrial Planets, 539, Heidelberg, Germany: Dordrecht, D. Reidel Publishing Co: 625–630, arXiv:astro-ph/0305500, Bibcode:2003ESASP.539..625J, ISBN 92-9092-849-2.

- ^ a b Buccino, A. P.; Lemarchand, G. A.; Mauas, P. J. D. (2006), "Ultraviolet radiation constraints around the circumstellar habitable zones", Icarus, 183 (2): 491–503, arXiv:astro-ph/0512291, Bibcode:2006Icar..183..491B, doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2006.03.007, ISSN 0019-1035, S2CID 2241081,

In near the 41% stars of the sample: HD19994, 70 Vir, 14 Her, 55 Cnc, 47 UMa, ε Eri and HD3651, there is no coincidence at all between the UV region and the HZ...the traditional HZ would not be habitable following the UV criteria exposed in this work.

External links

[edit]- Marcy, G.; et al. (February 12, 2002), A Planet Around Epsilon Eridani?, Exoplanets.org, archived from the original on July 9, 2011, retrieved May 18, 2011.

- Staff (July 8, 1998), "Astronomers discover a nearby star system just like our own Solar System", Joint Astronomy Centre, The University of Hawaii, archived from the original on May 8, 2011, retrieved February 24, 2011.

- Anonymous, "Epsilon Eridani", SolStation, The Sol Company, retrieved November 28, 2008.

- Tirion, Wil (2001), "Sky Map: Epsilon Eridani", Planet Quest, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, archived from the original on July 26, 2011, retrieved April 9, 2011.

- K-type main-sequence stars

- Solar-type stars

- BY Draconis variables

- Planetary systems with one confirmed planet

- Circumstellar disks

- Ursa Major moving group

- Local Bubble

- Stars with proper names

- Astronomical objects known since antiquity

- Eridanus (constellation)

- Bayer objects

- Durchmusterung objects

- Flamsteed objects

- Gliese and GJ objects

- Henry Draper Catalogue objects

- Hipparcos objects

- Bright Star Catalogue objects