Emmanuel Macron: Difference between revisions

Frenchpolit (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Frenchpolit (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 312: | Line 312: | ||

Despite its minority status in the legislature, Macron's government subsequently passed bills to ease the cost-of-living crisis,<ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.rfi.fr/en/business-and-tech/20220722-france-s-hung-parliament-passes-20-bn-euro-inflation-package |title=France's hung parliament passes 20-bn-euro inflation package |work=RFI |agency=AFP |date=22 July 2022 }}</ref> to end the [[COVID-19 pandemic in France|COVID]] "sanitary state of emergency",<!-- <ref>{{cite news |author=Huaxia |url=https://english.news.cn/europe/20220727/4fc5483771a24e449a25bd48db326c7c/c.html |title=French Parliament votes bill ending state of health emergency on Aug. 1 |agency=Xinhua |work=News.cn |date=27 July 2022 }}</ref> --><ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.rfi.fr/en/france/20220727-french-parliament-votes-to-end-covid-emergency-measures-border-control-still-possible |title=French parliament votes to end Covid emergency measures, border control still possible |work=RFI |date=27 July 2022 }}</ref> and to revive the French nuclear energy sector.<ref>{{cite news |first1=Perrine |last1=Mouterde |first2=Adrien |last2=Pécout |url=https://www.lemonde.fr/en/economy/article/2023/05/17/french-government-passes-bill-to-accelerate-the-construction-of-new-nuclear-reactors_6026936_19.html |title=French Parliament passes law to accelerate construction of new nuclear reactors |newspaper=Le Monde |date=17 May 2022 }}</ref> But at the end of 2022, the [[Borne government|Borne Cabinet]] had to repeatedly commit its responsibility (using the provisions of [[Article 49 of the French Constitution|Article 49.3 of the Constitution]]) to pass the 2023 Governement Budget and Social Security Budget.<ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.france24.com/en/economy/20221024-french-govt-survives-no-confidence-votes-after-forcing-through-budget |title=French govt survives no-confidence votes after forcing through budget |work=France 24 |date=24 October 2022 }}</ref><ref>{{cite news |first1=Jérémie |last1=Lamothe |first2=Mariama |last2=Darame |url=https://www.lemonde.fr/en/politics/article/2022/11/22/social-security-budget-french-pm-bypasses-assemblee-nationale-for-the-fifth-time_6005220_5.html |title=Social security budget: French PM bypasses Assemblée Nationale for the fifth time |newspaper=Le Monde |date=22 November 2022 }}</ref>. |

Despite its minority status in the legislature, Macron's government subsequently passed bills to ease the cost-of-living crisis,<ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.rfi.fr/en/business-and-tech/20220722-france-s-hung-parliament-passes-20-bn-euro-inflation-package |title=France's hung parliament passes 20-bn-euro inflation package |work=RFI |agency=AFP |date=22 July 2022 }}</ref> to end the [[COVID-19 pandemic in France|COVID]] "sanitary state of emergency",<!-- <ref>{{cite news |author=Huaxia |url=https://english.news.cn/europe/20220727/4fc5483771a24e449a25bd48db326c7c/c.html |title=French Parliament votes bill ending state of health emergency on Aug. 1 |agency=Xinhua |work=News.cn |date=27 July 2022 }}</ref> --><ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.rfi.fr/en/france/20220727-french-parliament-votes-to-end-covid-emergency-measures-border-control-still-possible |title=French parliament votes to end Covid emergency measures, border control still possible |work=RFI |date=27 July 2022 }}</ref> and to revive the French nuclear energy sector.<ref>{{cite news |first1=Perrine |last1=Mouterde |first2=Adrien |last2=Pécout |url=https://www.lemonde.fr/en/economy/article/2023/05/17/french-government-passes-bill-to-accelerate-the-construction-of-new-nuclear-reactors_6026936_19.html |title=French Parliament passes law to accelerate construction of new nuclear reactors |newspaper=Le Monde |date=17 May 2022 }}</ref> But at the end of 2022, the [[Borne government|Borne Cabinet]] had to repeatedly commit its responsibility (using the provisions of [[Article 49 of the French Constitution|Article 49.3 of the Constitution]]) to pass the 2023 Governement Budget and Social Security Budget.<ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.france24.com/en/economy/20221024-french-govt-survives-no-confidence-votes-after-forcing-through-budget |title=French govt survives no-confidence votes after forcing through budget |work=France 24 |date=24 October 2022 }}</ref><ref>{{cite news |first1=Jérémie |last1=Lamothe |first2=Mariama |last2=Darame |url=https://www.lemonde.fr/en/politics/article/2022/11/22/social-security-budget-french-pm-bypasses-assemblee-nationale-for-the-fifth-time_6005220_5.html |title=Social security budget: French PM bypasses Assemblée Nationale for the fifth time |newspaper=Le Monde |date=22 November 2022 }}</ref>. |

||

In March 2023, Macron's government passed a law raising the retirement age from 62 to 64, partly bypassing Parliament by resorting to the provisions of Article 49.3 of the Constitution in order to break the parliamentary deadlock;<ref>{{cite news |first1=Roger |last1=Cohen |first2=Aurelien |last2=Breeden |url=https://www.nytimes.com/live/2023/03/16/world/france-pension-vote |title=France's Pension Plan: Macron Pushes French Pension Bill Through Without Full Vote |newspaper=The New York Times |date=20 March 2023 |orig-date=16 March 2023 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230609170434/https://www.nytimes.com/live/2023/03/16/world/france-pension-vote |archive-date=2023-06-09 }}</ref> [[2023 French pension reform unrest|nationwide protests]] that had begun when the change was proposed increased after the vote. |

In March 2023, Macron's government passed a law raising the retirement age from 62 to 64, partly bypassing Parliament by resorting to the provisions of Article 49.3 of the Constitution in order to break the parliamentary deadlock;<ref>{{cite news |first1=Roger |last1=Cohen |first2=Aurelien |last2=Breeden |url=https://www.nytimes.com/live/2023/03/16/world/france-pension-vote |title=France's Pension Plan: Macron Pushes French Pension Bill Through Without Full Vote |newspaper=The New York Times |date=20 March 2023 |orig-date=16 March 2023 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230609170434/https://www.nytimes.com/live/2023/03/16/world/france-pension-vote |archive-date=2023-06-09 }}</ref> [[2023 French pension reform unrest|nationwide protests]] that had begun when the change was proposed increased after the vote. On 20 March, his Cabinet survived a cross-party [[motion of no-confidence]] by only nine votes, the slimmest margin since the 1990s.<ref>https://www.lemonde.fr/politique/article/2023/03/21/a-neuf-voix-pres-la-principale-motion-de-censure-a-ete-rejetee-a-l-assemblee-nationale_6166305_823448.html</ref> |

||

On 12 June 2023, Macron's Cabinet, led by Prime Minister Borne, survived its 17th motion of no-confidence since the beginning of the 16th legislature: the motion, brought forward by left-wing NUPES coalition in response to the use of constitutional article 40 to block an opposition-sponsored amendment reintroducing the 62-year retirement age on the centrist [[Liberties, Independents, Overseas and Territories|LIOT]] group's [[opposition day]], received 239 votes, 50 votes short of the threshold of 289 required to overthrow the government, and failed.<ref>{{cite news |first=Célestine |last=Gentilhomme |url=https://www.lefigaro.fr/politique/retraites-la-motion-de-censure-de-la-nupes-rejetee-a-l-assemblee-20230612 |title=Retraites: la motion de censure de la Nupes rejetée à l'Assemblée |newspaper=Le Figaro |date=12 June 2023 |lang=fr }}</ref> |

On 12 June 2023, Macron's Cabinet, led by Prime Minister Borne, survived its 17th motion of no-confidence since the beginning of the 16th legislature: the motion, brought forward by left-wing NUPES coalition in response to the use of constitutional article 40 to block an opposition-sponsored amendment reintroducing the 62-year retirement age on the centrist [[Liberties, Independents, Overseas and Territories|LIOT]] group's [[opposition day]], received 239 votes, 50 votes short of the threshold of 289 required to overthrow the government, and failed.<ref>{{cite news |first=Célestine |last=Gentilhomme |url=https://www.lefigaro.fr/politique/retraites-la-motion-de-censure-de-la-nupes-rejetee-a-l-assemblee-20230612 |title=Retraites: la motion de censure de la Nupes rejetée à l'Assemblée |newspaper=Le Figaro |date=12 June 2023 |lang=fr }}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 12:42, 17 June 2023

Emmanuel Macron | |

|---|---|

Macron in 2023 | |

| President of France | |

| Assumed office 14 May 2017 | |

| Prime Minister | Édouard Philippe Jean Castex Élisabeth Borne |

| Preceded by | François Hollande |

| Minister of Economics, Industry and Digital Affairs | |

| In office 26 August 2014 – 30 August 2016 | |

| Prime Minister | Manuel Valls |

| Preceded by | Arnaud Montebourg |

| Succeeded by | Michel Sapin |

| Assistant Secretary-General of the Presidency | |

| In office 15 May 2012 – 15 July 2014 | |

| President | François Hollande |

| Preceded by | Jean Castex |

| Succeeded by | Laurence Boone |

| Additional positions | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Emmanuel Jean-Michel Frédéric Macron 21 December 1977 Amiens, Somme, France |

| Political party | Renaissance (2016–present) |

| Other political affiliations |

|

| Spouse | |

| Parent |

|

| Relatives | Laurence Auzière-Jourdan (stepdaughter) |

| Residence | Élysée Palace |

| Alma mater | |

| Awards | List of honours and decorations |

| Signature |  |

| Co-Prince of Andorra[note 1] | |

| Reign | 14 May 2017 - present |

| Predecessor | François Hollande |

| ||

|---|---|---|

President (2017–present)

Media gallery |

||

Emmanuel Jean-Michel Frédéric Macron (Template:IPA-fr; born 21 December 1977) is a French politician serving as President of France since 2017. Ex officio, he is also one of the two Co-Princes of Andorra. Earlier, Macron served as Minister of Economics, Industry and Digital Affairs under President François Hollande from 2014 to 2016 and Assistant Secretary-General of the Presidency from 2012 to 2014.

Born in Amiens, he studied philosophy at Paris Nanterre University, later completing a master's degree in public affairs at Sciences Po and graduating from the École nationale d'administration in 2004. Macron worked as a senior civil servant at the Inspectorate General of Finances and later became an investment banker at Rothschild & Co.

Macron was appointed Élysée deputy secretary-general by President François Hollande shortly after his election in May 2012, making him one of Hollande's senior advisers. He was appointed to the Government of Prime Minister Manuel Valls as Minister of Economics, Industry and Digital Affairs in August 2014. In this role, Macron championed a number of business-friendly reforms. He resigned in August 2016, launching a campaign for the 2017 presidential election. Although Macron had been a member of the Socialist Party from 2006 to 2009, he ran in the election under the banner of En Marche, a centrist and pro-European political movement he founded in April 2016.

Partly thanks to the Fillon affair which sank The Republicans nominee François Fillon, Macron topped the ballot in the first round of voting, before he was elected President of France on 7 May 2017 with 66.1% of the vote in the second round, defeating Marine Le Pen of the National Front. At the age of 39, Macron became the youngest president in French history. In the 2017 legislative election in June, Macron's party, renamed La République En Marche! (LREM), secured a majority in the National Assembly. He appointed Édouard Philippe as prime minister until his resignation in 2020, when he appointed Jean Castex. Macron was elected to a second term in the 2022 presidential election, again defeating Le Pen, thus becoming the first French presidential candidate to win reelection since Jacques Chirac in 2002.[1] However, in the 2022 legislative election, his centrist coalition lost its absolute majority, resulting in a hung parliament and the formation of France's first minority government since the fall of the Bérégovoy government in 1993.

During his presidency, Macron has overseen several reforms to labour laws, taxation and pensions; he has pursued a renewable energy transition. Dubbed "president of the rich" by political opponents,[2] increasing protests against his domestic reforms and demanding his resignation marked the first years of his presidency, culminating in 2018–2020 with the yellow vests protests and the pension reform strike. From 2020, he led France's response to the COVID-19 pandemic and vaccination rollout. In 2023, the government of his prime minister, Elisabeth Borne, passed legislation raising the retirement age from 62 to 64; the pension reforms proved controversial and led to public sector strikes and violent protests. In foreign policy, he called for reforms to the European Union (EU) and signed bilateral treaties with Italy and Germany. Macron conducted $45-billion trade and business agreements with China during the China–United States trade war and oversaw a dispute with Australia and the United States over the AUKUS security pact. He continued Opération Chammal in the war against the Islamic State and joined in the international condemnation of the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Early life

Macron was born on 21 December 1977 in Amiens. He is the son of Françoise Macron (née Noguès), a physician, and Jean-Michel Macron, professor of neurology at the University of Picardy.[3][4] The couple divorced in 2010. He has two siblings, Laurent, born in 1979, and Estelle, born in 1982. Françoise and Jean-Michel's first child was stillborn.[5]

The Macron family legacy is traced back to the village of Authie, Picardy.[6] One of his paternal great-grandfathers, George William Robertson, was English, and was born in Bristol, United Kingdom.[7][8] His maternal grandparents, Jean and Germaine Noguès (née Arribet), are from the Pyrenean town of Bagnères-de-Bigorre, Gascony.[9] He commonly visited Bagnères-de-Bigorre to visit his grandmother Germaine, whom he called "Manette".[10] Macron associates his enjoyment of reading[11] and his leftward political leanings to Germaine, who, after coming from a modest upbringing of a stationmaster father and a housekeeping mother, became a teacher then a principal, and died in 2013.[12]

Although raised in a non-religious family, Macron was baptized a Catholic by his own request at age 12; he is agnostic today.[13]

Macron was educated mainly at the Jesuit institute Lycée la Providence[14] in Amiens[15] before his parents sent him to finish his last year of school[16] at the elite Lycée Henri-IV in Paris, where he completed the high school curriculum and the undergraduate program with a "Bac S, Mention Très bien". At the same time, he was nominated for the "Concours général" (most selective national level high school competition) in French literature and received his diploma for his piano studies at Amiens Conservatory.[17] His parents sent him off to Paris due to their alarm at the bond he had formed with Brigitte Auzière, a married teacher with three children at Jésuites de la Providence, who later became his wife.[18]

In Paris, Macron twice failed to gain entry to the École normale supérieure.[19][20][21] He instead studied philosophy at the University of Paris-Ouest Nanterre La Défense, obtaining a DEA degree (a master level degree), with a thesis on Machiavelli and Hegel.[14][22] Around 1999 Macron worked as an editorial assistant to Paul Ricoeur, the French Protestant philosopher who was then writing his last major work, La Mémoire, l'Histoire, l'Oubli. Macron worked mainly on the notes and bibliography.[23][24] Macron became a member of the editorial board of the literary magazine Esprit.[25]

Macron did not perform national service because he was pursuing his graduate studies. Born in December 1977, he belonged to the last year when service was mandatory.[26][27]

Macron obtained a master's degree in public affairs at Sciences Po, majoring in "Public Guidance and Economy" before training for a senior civil service career at the selective École nationale d'administration (ENA), training at the French Embassy in Nigeria[28] and at the prefecture of Oise before graduating in 2004.[29]

Professional career

Inspector of Finances

After graduating from ENA in 2004, Macron became an Inspector in the Inspection générale des finances (IGF), a branch of the Finance Ministry.[23] Macron was mentored by Jean-Pierre Jouyet, the then-head of the IGF.[30] During his time as an Inspector of Finances, Macron gave lectures during the summer at the "prep'ENA" (a special cram school for the ENA entrance examination) at IPESUP, an elite private school specializing in preparation for the entrance examinations of the Grandes écoles, such as HEC or Sciences Po.[31][32][33]

In 2006, Laurence Parisot offered him the job of managing director for Mouvement des Entreprises de France, the largest employer federation in France, but he declined.[34]

In August 2007, Macron was appointed deputy rapporteur for Jacques Attali's "Commission to Unleash French Growth".[15] In 2008, Macron paid €50,000 to buy himself out of his government contract.[35] He then became an investment banker in a highly-paid position at Rothschild & Cie Banque.[36][37] In March 2010, he was appointed to the Attali Commission as a member.[38]

Investment banker

In September 2008, Macron left his job as an Inspector of Finances and took a position at Rothschild & Cie Banque.[39] Macron was inspired to leave the government due to the election of Nicolas Sarkozy to the presidency. He was originally offered the job by François Henrot. His first responsibility at Rothschild & Cie Banque was assisting with the acquisition of Cofidis by Crédit Mutuel Nord Europe.[40]

Macron formed a relationship with Alain Minc, a businessman on the supervisory board of Le Monde.[41] In 2010, Macron was promoted to partner with the bank after working on the recapitalization of Le Monde and the acquisition by Atos of Siemens IT Solutions and Services.[42] In the same year, Macron was appointed as managing director and put in charge of Nestlé's acquisition of one of Pfizer's largest subsidiaries based around baby drinks. His share of the fees on this €9 billion deal made Macron a millionaire.[43]

In February 2012, he advised businessman Philippe Tillous-Borde, the CEO of the Avril Group.[44]

Macron reported that he had earned €2 million between December 2010 and May 2012.[45] Official documents show that between 2009 and 2013, Macron had earned almost €3 million.[46] He left Rothschild & Cie in 2012.[47][48]

Political career

In his youth, Macron worked for the Citizen and Republican Movement for two years, but he never applied to be a member.[49][45] Macron was an assistant for Mayor Georges Sarre of the 11th arrondissement of Paris during his time at Sciences Po.[50] Macron had been a member of the Socialist Party since he was 24, but renewed his subscription to the party from only 2006 to 2009.[51][52][53]

Macron met François Hollande through Jean-Pierre Jouyet in 2006 and joined his staff in 2010.[52] In 2007, Macron attempted to run for a seat in the National Assembly in Picardy under the Socialist Party label in the 2007 legislative elections, however, his application was declined.[54] Macron was offered the chance to be the deputy chief of staff to Prime Minister François Fillon in 2010, though he declined.[55]

Deputy Secretary-General of the Élysée

On 15 May 2012, Macron became the deputy secretary-general of the Élysée, a senior role in President François Hollande's staff.[56][29] Macron served with Nicolas Revel. He served under the secretary-general, Pierre-René Lemas.

During the summer of 2012, Macron put forward a proposal that would increase the 35-hour work week to 37 hours until 2014. He also tried to hold back the large tax increases on the highest earners that were planned by the government. Hollande refused Macron's proposals.[57] Nicolas Revel, the other deputy secretary-general of the Élysée whom he was serving with, opposed Macron on a proposed budget responsibility pact. Revel generally worked on social policy.[58]

Macron was one of the deciding voices on not regulating the salaries of CEOs.[59]

On 10 June 2014, it was announced that Macron had resigned from his role and was replaced by Laurence Boone.[60] Reasons for his departure were that he was disappointed to not be included in the first Government of Manuel Valls and also frustrated by his lack of influence in the reforms proposed by the government.[58] This was following the appointment of Jean-Pierre Jouyet as chief of staff.[61]

Jouyet said that Macron left to "continue personal aspirations"[62] and create his own financial consultancy firm.[63] It was later reported that Macron was planning to create an investment firm that would attempt to fund educational projects.[49] Macron was shortly afterwards employed at the University of Berlin with the help of businessman Alain Minc. Macron was awarded the position of research fellow. Macron had also sought a position at Harvard University.[64]

Macron was offered a chance to be a candidate in the municipal elections in 2014 in his hometown of Amiens. He declined the offer.[65] Manuel Valls attempted to appoint Macron as the Budget Minister, but François Hollande rejected the idea due to Macron's never being elected before.[61]

Minister of Economics and Industry

He was appointed as the Minister of Economics and Industry in the second Valls Cabinet on 26 August 2014, replacing Arnaud Montebourg.[66] He was the youngest Minister of Economics since Valéry Giscard d'Estaing in 1962.[67] Macron was branded by the media as the "Anti-Montebourg" due to being pro-EU and much more moderate, while Montebourg was eurosceptic and left-wing.[68] As Minister of Economics, Macron was at the forefront of pushing through business-friendly reforms. On 17 February 2015, prime minister Manuel Valls pushed Macron's signature law package through a reluctant parliament using the special 49.3 procedure.[69]

Macron increased the French share in the company Renault from 15% to 20% and then enforced the Florange law which grants double voting rights on shares registered for more than two years unless two-thirds of shareholders vote to overturn it.[70] This gave the French state a minority share in the company though Macron later stated that the government would limit its powers within Renault.[71]

Macron was widely criticized for being unable to prevent the closing down of an Ecopla factory in Isère.[72]

In August 2015, Macron said that he was no longer a member of the Socialist Party and was an independent.[51]

Macron Law

The "Macron Law" was Macron's signature law package that was eventually pushed through parliament using the 49.3 procedure.[69]

After the "Law on Growth and Purchasing Power" brought on by Arnaud Montebourg with the aim to "restore 6 billion euros of purchasing power" to the French public.[73] Macron presented the Macron Law to a council of ministers. The law intended to rejuvenate the French economy by fixing regulations based around Sunday work, transport and driving licences, public sector jobs and the transport market.[74] Manuel Valls, under the fear that the law would not find a majority in the National Assembly, decided to push the law through with the 49.3 procedure.[75] The law was adopted on 10 April 2015.[76]

The OECD estimated that the Macron Law would generate a "0.3% increase in GDP over five-years and a 0.4% increase over 10-years"[77] Ludovic Subran, the chief economist at credit insurance company, Euler Hermes, estimated that Macron Law would give France a GDP increase of 0.5%.[78]

2017 presidential campaign

Formation of En Marche and resignation from government

Macron first became known to the French public after his appearance on the French TV programme "Des Paroles Et Des Actes" in March 2015.[79] Before forming his political party En Marche, Macron had hosted a series of events with him speaking in public, his first one in March 2015 in Val-de-Marne.[80] Macron threatened to leave Manuel Valls' second government over the proposed reform on removing dual-nationality from terrorists.[81][82] He also took various foreign trips, including one to Israel where he spoke on the advancement of digital technology.[83]

Tensions around the question of Macron's loyalty to the Valls government and Hollande himself increased when Hollande and Valls turned down a proposal for a law put forward by Macron. The law, titled "Macron 2" was going to be much bigger than the original Macron law with a larger aim of making the French economy competitive.[84][85] Macron was given the chance to insert his opinion into the El Khomri law and put specific parts of "Macron 2" into the law though El Khomri could overturn these with help of other ministers.

Amid tensions and deterioration of relations with the current government, Macron founded an independent political party, En Marche, in Amiens on 6 April 2016.[86] A liberal,[87] progressive[88][89] political movement that gathered huge media coverage when it was first established,[90] the party and Macron were both reprimanded by President Hollande and the question of Macron's loyalty to the government was raised.[91][92] Several MEPs spoke out in support for the movement[93] though the majority of the Socialist Party spoke against En Marche including Manuel Valls,[94] Michel Sapin,[95] Axelle Lemaire and Christian Eckert.[96]

In June 2016, support for Macron and his movement, En Marche, began to grow in the media with L'Express, Les Echos, Le 1 and L'Opinion beginning to voice public support for Macron.[97] Following several controversies surrounding trade unionists and their protests, major newspapers began to run stories about Macron and En Marche on their front page with mainly positive press.[98] This was criticized hugely by the far-left in France and the far-right with the term "Macronite" being coined to describe the pro-Macron influence within the press.[99][100][101] The term has been expanded among the left-wing to also criticize the centrist leanings of most newspapers and their influence among left-wing voter bases.[102][103][104]

Macron was invited to attend a festival in Orléans by mayor Olivier Carré in May 2016, the festival is organized every year to celebrate Orléans' liberation by Joan of Arc.[105] France Info and LCI reported that Macron had attached the Republican values of the Fifth Republic to Joan of Arc and then in a speech, he compared himself to Joan of Arc.[106][107] Macron later went to Puy du Fou and declared he was "not a socialist" in a speech amid rumours he was going to leave the current government.[108]

On 30 August 2016, Macron resigned from the government ahead of the 2017 presidential election,[109][110] to devote himself to his En Marche movement.[111][112] There had been rising tensions and several reports that he wanted to leave the Valls government since early 2015.[113] Macron initially planned to leave after the cancellation of his "Macron 2" law[85] but after a meeting with President François Hollande, he decided to stay and an announcement was planned to declare that Macron was committed to the government[114] (though the announcement was pushed back due to the attacks in Nice and Normandy[115][116]). Michel Sapin was announced as Macron's replacement.[117] Speaking on Macron's resignation, Hollande said he had been "betrayed".[118] According to an IFOP poll, 84% of French agreed with Macron's decision to resign.[119]

First round of the presidential election

Macron first showed intention to run with the formation of En Marche, but following his resignation from the government, he was able to spend more time dedicating himself to his movement. He first announced that he was considering running for president in April 2016,[120] and after his resignation from the position of economy minister, media sources began to find patterns in Macron's fundraising and typical presidential campaign fundraising tactics.[121] In October 2016, Macron criticized Hollande's goal of being a "normal" president, saying that France needed a more "Jupiterian presidency".[122]

On 16 November 2016, Macron formally declared his candidacy for the French presidency after months of speculation. In his announcement speech, Macron called for a "democratic revolution" and promised to "unblock France".[123] Macron had wished that Hollande would join the race several months beforehand, saying that Hollande was the legitimate candidate for the Socialist Party.[124][125] A book was published on 24 November 2016 by Macron to support his campaign titled "Révolution", the book sold nearly 200,000 copies during its printing run and was one of the best selling books in France in 2016.[126][127][128]

Shortly after announcing his run, Jean-Christophe Cambadélis and Manuel Valls both asked Macron to run in the Socialist Party presidential primary though Macron ultimately refused.[129][130] Jean-Christophe Cambadélis began to threaten to exclude members who associated or supported Macron following Lyon mayor Gérard Collomb's declaration of support for Macron.[131]

Macron's campaign, headed by French economist Sophie Ferracci, announced in December 2016 that it had raised 3.7 million euros in donations without public funding (as En Marche was not a registered political party).[132][133] This was three times the budget of then-front runner Alain Juppé.[134] Macron came under criticism from several individuals, including Benoît Hamon who requested Macron reveal a list of his donors accusing him of conflicts of interest due to Macron's past at Rothschilds.[135] Macron replied to this, calling Hamon's behaviour "demagogic".[136] It was later reported by journalists Marion L'Hour and Frédéric Says that Macron had spent €120,000 on setting up dinners and meetings with various personalities within the media and in French popular culture while he was minister.[137][138][139] Macron was then accused by deputies, Christian Jacob and Philippe Vigier of using this money to further the representation of En Marche in French political life.[140][141] Michel Sapin, his successor and Minister of Economics saw nothing illegal about Macron's actions, saying that Macron had the right to spend the funds.[142] Macron said in response to these allegations that it was "defamatory" and that none of the ministerial budget had been spent on his party.[138]

Macron's campaign enjoyed considerable coverage from the media.[143][144][145][146][147] Mediapart reported that Macron had over fifty magazine covers dedicated purely to him compared to Melenchon's "handful" despite similar followings online and both having large momentum during the campaign.[148] Macron has been consistently labelled by the far-left and far-right as the "media candidate" and has been viewed as such in opinion polls.[149][150][151] He is friends with the owners of Le Monde[152] and Claude Perdiel the former owner of Nouvel Observateur.[153] Many observers have compared Macron's campaign to a product being sold[154] due to Maurice Lévy, a former CEO using marketing tactics to try to advance Macron's presidential ambitions.[155][156] The magazine Marianne has reported that BFMTV, whose owner is Patrick Drahi, has broadcast more coverage of Macron than of all four main candidates combined,[157] Marianne has said this may be due to Macron's campaign having links with Drahi through a former colleague of Drahi, Bernard Mourad.[158][159]

After a range of comparisons to centrist François Bayrou, Bayrou announced he was not going to stand in the presidential election and instead form an electoral alliance with Macron which went into effect on 22 February 2017, and has since lasted with En Marche and the Democratic Movement becoming allies in the National Assembly.[160][161] Following this, Macron's poll ratings began to rise and after several legal issues surrounding François Fillon become publicized, Macron overtook him in the polls to become the front runner after polls showed him beating National Front candidate Marine Le Pen in the second round.[162][163]

Macron attracted criticism for the time taken to spell out a formal program during his campaign; despite declaring in November that he had still not released a complete set of proposals by February, attracting both attacks from critics and concern among allies and supporters.[164] He eventually laid out his 150-page formal program on 2 March, publishing it online and discussing it at a marathon press conference that day.[165]

Macron accumulated a wide array of supporters, securing endorsements from François Bayrou of the Democratic Movement (MoDem), MEP Daniel Cohn-Bendit, the ecologist candidate François de Rugy of the primary of the left, and Socialist MP Richard Ferrand, secretary-general of En Marche, as well as numerous others – many of them from the Socialist Party, but also a significant number of centrist and centre-right politicians.[166] The Grand Mosque of Paris urged French Muslims to vote en masse for Macron.[167]

On 23 April 2017, Macron received the most votes in the first round of the presidential election, with 24% of the overall vote and more than 8 million votes all together. He progressed to the second round with Marine Le Pen. Former candidates François Fillon and Benoît Hamon voiced their support for Macron.[168]

Second round of the presidential election

Macron qualified for the run-off against National Front candidate Marine Le Pen on 23 April 2017, after coming first place in the vote count. Following the announcement of his qualification, François Fillon and Benoît Hamon expressed support for Macron.[168] President François Hollande also endorsed Macron.[169] Many foreign politicians voiced support for Macron in his bid against right-wing populist candidate Marine Le Pen, including European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker, German Chancellor Angela Merkel,[170] and former US President Barack Obama.[171]

A debate was arranged between Macron and Le Pen on 3 May 2017. The debate lasted for 2 hours and Macron was considered the winner according to opinion polls.[172]

In March 2017, Macron's digital campaign manager, Mounir Mahjoubi, told Britain's Sky News that Russia is behind "high level attacks" on Macron, and said that its state media are "the first source of false information". He said: "We are accusing RT (formerly known as Russia Today) and Sputnik News (of being) the first source of false information shared about our candidate ...".[173]

Two days before the French presidential election on 7 May, it was reported that nine gigabytes of Macron's campaign emails had been anonymously posted to Pastebin, a document-sharing site. These documents were then spread onto the imageboard 4chan which led to the hashtag "#macronleaks" trending on Twitter.[174][175] In a statement on the same evening, Macron's political movement, En Marche, said: "The En Marche movement has been the victim of a massive and coordinated hack this evening which has given rise to the diffusion on social media of various internal information".[176] Macron's campaign had been presented a report before in March 2017 by the Japanese cyber security firm Trend Micro detailing how En Marche had been the target of phishing attacks.[177] Trend Micro said that the group conducting these attacks was the Russian hacking group Fancy Bear that was also accused of hacking the Democratic National Committee on 22 July 2016.[177] These same emails were verified and released in July 2017 by WikiLeaks.[178] This was following Le Pen accusing Macron of tax avoidance.[179]

On 7 May 2017, Macron was elected President of France with 66.1% of the vote compared to Marine Le Pen's 33.9%. The election had record abstention at 25.4% and 8% of ballots being blank or spoilt.[180] Macron resigned from his role as president of En Marche[181] and Catherine Barbaroux became interim leader.[182]

First term as President of France

Macron qualified for the runoff after the first round of the election on 23 April 2017. He won the second round of the presidential election on 7 May 2017 by a landslide according to preliminary results,[183] making the candidate of the National Front, Marine Le Pen, concede.[184] At 39, he became the youngest president in French history and the youngest French head of state since Napoleon.[185][186][187] He is also the first president of France born after the establishment of the Fifth Republic in 1958.

Macron formally became president on 14 May.[188] He appointed Patrick Strzoda as his chief of staff[189] and Ismaël Emelien as his special advisor for strategy, communication and speeches.[190] On 15 May, he appointed Édouard Philippe of the Republicans as Prime Minister.[191][192] On the same day, he made his first official foreign visit, meeting in Berlin with Angela Merkel, the Chancellor of Germany. The two leaders emphasised the importance of France–Germany relations to the European Union.[193] They agreed to draw up a "common road map" for Europe, insisting that neither was against changes to the Treaties of the European Union.[194]

In the 2017 legislative election, Macron's party La République En Marche and its Democratic Movement allies secured a comfortable majority, winning 350 seats out of 577.[195] After The Republicans emerged as the winners of the Senate elections, government spokesman Christophe Castaner stated the elections were a "failure" for his party.[196]

On 3 July 2020, Macron appointed the centre-right Jean Castex as the Prime Minister of France. Castex has been described as being seen to be a social conservative and was a member of The Republicans.[197] The appointment was described as a "doubling down on a course that is widely seen as centre-right in economic terms".[198]

Domestic policy

In his first few months as president, Macron pressed for the enactment of a package of reforms on public ethics, labour laws, taxes, and law enforcement agency powers.[citation needed]

Anti-corruption

In response to Penelopegate, the National Assembly passed a part of Macron's proposed law to stop mass corruption in French politics by July 2017, banning elected representatives from hiring family members.[199] Meanwhile, the second part of the law scrapping a constituency fund was scheduled for voting after Senate objections.[200]

Macron's plan to give his wife an official role within government came under fire with criticisms ranging from its being undemocratic to what critics perceive as a contradiction to his fight against nepotism.[201] Following an online petition of nearly 290,000 signatures on change.org Macron abandoned the plan.[202] On 9 August, the National Assembly adopted the bill on public ethics, a key theme of Macron's campaign, after debates on the scrapping the constituency funds.[203]

Labour policy and unions

Macron aims to shift union-management relations away from the adversarial lines of the current French system and toward a more flexible, consensus-driven system modelled after Germany and Scandinavia.[204][205] He has also pledged to act against companies employing cheaper labour from eastern Europe and in return affecting jobs of French workers, what he has termed as "social dumping". Under the Posted Workers Directive 1996, eastern European workers can be employed for a limited time at the salary level in eastern European countries, which has led to dispute between the EU states.[206]

The French government announced the proposed changes to France's labour rules ("Code du Travail"), being among the first steps taken by Macron and his government to galvanize the French economy.[207] Macron's reform efforts have encountered resistance from some French trade unions.[208] The largest trade union, the CFDT, has taken a conciliatory approach to Macron's push and has engaged in negotiations with the president, while the more militant CGT is more hostile to reforms.[204][205] Macron's labour minister, Muriel Pénicaud, is overseeing the effort.[209]

The National Assembly including the Senate approved the proposal, allowing the government to loosen the labour laws after negotiations with unions and employers' groups.[210] The reforms, which were discussed with unions, limit payouts for dismissals deemed unfair and give companies greater freedom to hire and fire employees as well as to define acceptable working conditions. The president signed five decrees reforming the labour rules on 22 September.[211] Government figures released in October 2017 revealed that during the legislative push to reform the labour code, the unemployment rate had dropped 1.8%, the biggest since 2001.[212]

On 16 March 2023 Macron passed a law raising the retirement age from 62 to 64,[213] leading to protests.[214]

Migrant crisis

Speaking on refugees and, specifically, the Calais Jungle, Macron said on 16 January 2018 that he would not allow another refugee camp to form in Paris before outlining the government policy towards immigration and asylum.[215] He has also announced plans to speed up asylum applications and deportations but give refugees better housing.[216]

On 23 June 2018, President Macron said: "The reality is that Europe is not experiencing a migration crisis of the same magnitude as the one it experienced in 2015", "a country like Italy has not at all the same migratory pressure as last year. The crisis we are experiencing today in Europe is a political crisis".[217] In November 2019, Macron introduced new immigration rules to restrict the number of refugees reaching France, while stating to "take back control" of the immigration policy.[218]

Economic policy

Pierre de Villiers, then-Chief of the General Staff of the Armies, stepped down on 19 July 2017 following a confrontation with Macron.[219] De Villiers cited the military budget cut of €850 million as the main reason he was stepping down. Le Monde later reported that De Villiers told a parliamentary group, "I will not let myself be fucked like this."[220] Macron named François Lecointre as De Villiers' replacement.[221]

Macron's government presented its first budget on 27 September, the terms of which reduced taxes as well as spending to bring the public deficit in line with the EU's fiscal rules.[222] The budget replaced the wealth tax with one targeting real estate, fulfilling Macron's campaign pledge to scrap the wealth tax.[2] Before it was replaced, the tax collected up to 1.5% of the wealth of French residents whose global worth exceeded €1.3m.[223]

In February 2017, Macron announced a plan to offer voluntary redundancy in an attempt to further cut jobs from the French civil service.[224] In December 2019, Macron informed that he would scrap the 20th-century pension system and introduce a single nations pension system managed by the state.[225] In January 2020, after weeks of public transport shutdown and vandalization across Paris against the new pension plan, Macron compromised on the plan by revising the retirement age.[226] In February, the pension overhaul was adopted by decree using Article 49 of the French constitution.[227]

Terrorism

In July 2017, the Senate approved its first reading of a controversial bill with stricter anti-terror laws, a campaign pledge of Macron. The National Assembly voted on 3 October to pass the bill 415–127, with 19 abstentions. Interior Minister Gérard Collomb described France as being "still in a state of war" ahead of the vote, with the 1 October Marseille stabbing having taken place two days prior. The Senate then passed the bill on its second reading by a 244–22 margin on 18 October. Later that day Macron stated that 13 terror plots had been foiled since 2017 began. The law replaced the state of emergency in France and made some of its provisions permanent.[228]

The bill was criticized by human rights advocates. A public poll by Le Figaro showed 57% of the respondents approved it even though 62% thought it would encroach on personal freedoms.[229]

The law gives authorities expanded power to search homes, restrict movement, close places of worship,[230] and search areas around train stations as well as international ports and airports. It was passed after modifications to address concerns about civil liberties. The most punitive measures will be reviewed annually and are scheduled to lapse by the end of 2020.[231] The bill was signed into law by Macron on 30 October 2017. He announced that starting 1 November, it would bring an end to the state of emergency.[232]

Civil rights

Visiting Corsica in February 2018, Macron sparked controversy when he rejected Corsican nationalist wishes for Corsican as an official language[233] but offered to recognize Corsica in the French constitution.[234]

Macron also proposed a plan to "reorganise" the Islamic religion in France saying: "We are working on the structuring of Islam in France and also on how to explain it, which is extremely important – my goal is to rediscover what lies at the heart of laïcité, the possibility of being able to believe as not to believe, in order to preserve national cohesion and the possibility of having free consciousness." He declined to reveal further information about the plan.[235]

Freedom of expression

President Emmanuel Macron and his government proclaim their support for freedom of expression.[236] Macron responded to the protests about Charlie Hebdo's cartoon of the Prophet of Islam: "We will not disavow the cartoons, the drawings, even if others recoil."[237]

In 2019, a court convicted two men for 'contempt' after they burnt an effigy depicting President Macron during a peaceful protest. Parliament is currently discussing a new law that criminalizes the use of images of law enforcement officials on social media.[236]

In 2021 lawyers for the French president are suing after the large images appeared in the Var in the south of France.[238]

Michel-Ange Flori, who created and pasted the image on billboards, told the local newspaper he had been summoned by local police. "They confirmed that there had been a complaint from the Elysée," Flori told Var-Matin. "I was surprised and shocked."[238]

He later tweeted: "In Macron-land, showing the Prophet's rear is satire, making fun of Macron as a dictator is blasphemy," referring to the satirical newspaper Charlie Hebdo's controversial caricatures of the Prophet Muhammed.[238]

Foreign policy and national defence

Macron attended the 2017 Brussels summit on 25 May 2017, his first NATO summit as president of France. At the summit, he met US President Donald Trump for the first time. The meeting was widely publicized due to a handshake between the two of them being characterized as a "power-struggle".[239][240]

On 29 May 2017, Macron met with Vladimir Putin at the Palace of Versailles. The meeting sparked controversy when Macron denounced Russia Today and Sputnik, accusing the news agencies of being "organs of influence and propaganda, of lying propaganda".[241][242] Macron also urged cooperation in the conflict against ISIS and warned that France would respond with force in Syria if chemical weapons are used.[243] In response to the chemical attack in Douma, Syria in 2018, Macron directed French participation in airstrikes against Syrian government sites, coordinated with the United States and the United Kingdom.[244][245]

In his first major foreign policy speech on 29 August, President Macron stated that fighting Islamist terrorism at home and abroad was France's top priority. Macron urged a tough international stance to pressure North Korea into negotiations, on the same day it fired a missile over Japan. He also affirmed his support for the Iranian nuclear deal and criticized Venezuela's government as a "dictatorship". He added that he would announce his new initiatives on the future of the European Union after the German elections in September.[246] At the 56th Munich Security Conference in February, Macron presented his 10-year vision policy to strengthen the European Union. Macron remarked larger budget, integrated capital markets, effective defence policy and quick decision-making holds the key for Europe. Adding that reliance on NATO and especially the US and the UK was not good for Europe, and a dialogue must be established with Russia.[247]

Prior to the 45th G7 summit in Biarritz, France, Macron hosted Vladimir Putin at the Fort de Brégançon, stating that "Russia fully belongs within a Europe of values."[248] At the summit itself, Macron was invited to attend on the margins by Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif. Macron, who "attempted a high-risk diplomatic gambit", thought that the Foreign Minister of Iran might be able to defuse the tense situation over the Iranian nuclear programme in spite of the recent uptick in tensions between the Islamic Republic and the United States and Britain.[249]

In March 2019, at a time when China–U.S. economic relations were troubled with a trade war underway, Macron and Chinese leader Xi Jinping signed a series of 15 large-scale trade and business agreements totaling 40 billion euros ($45 billion USD) which covered many sectors over a period of years.[250] This included a €30 billion purchase of airplanes from Airbus. Going beyond aviation, the new trade agreement covered French exports of chicken, a French-built offshore wind farm in China, a Franco-Chinese cooperation fund, as well as billions of Euros of co-financing between BNP Paribas and the Bank of China. Other plans included billions of euros to be spent on modernizing Chinese factories, as well as new ship building.[251]

In July 2020, Macron called for sanctions against Turkey for the violation of Greece's and Cyprus' sovereignty, saying it is "not acceptable that the maritime space of (EU) member states be violated and threatened."[252] He also criticized Turkish military intervention in Libya.[253][254] Macron said that "We have the right to expect more from Turkey than from Russia, given that it is a member of NATO."[255]

In 2021, Macron was reported as saying Northern Ireland was not truly part of the United Kingdom following disputes with UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson over implementations of the Northern Ireland protocol.[256] He later denied this, saying he was referring to the fact that Great Britain is separated from Northern Ireland by sea in reference to the Irish Sea border.[257][258]

French-U.S. relations became tense in September 2021 due to fallout from the AUKUS security pact between the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia. The security pact is directed at countering Chinese power in the Indo-Pacific region. As part of the agreement, the U.S. agreed to provide nuclear-powered submarines to Australia. After entering into AUKUS, the Australian government canceled an agreement that it had made with France for the provision of French conventionally powered submarines, angering the French government.[259] On 17 September, France recalled its ambassadors from Australia and the US for consultations.[260] Despite tension in the past, France had never before withdrawn its ambassador to the United States.[261] After a call between Macron and U.S. President Joe Biden on request from the latter, the two leaders agreed to reduce bilateral tensions, and the White House acknowledged the crisis could have been averted if there had been open consultations between allies.[262][263]

On 26 November 2021, Macron signed with the Italian Prime Minister Mario Draghi the "Quirinal Treaty" at the Quirinal Palace, in Rome.[264] The treaty is aimed to promote the convergence and coordination of French and Italian positions in matters of European and foreign policies, security and defence, migration policy, economy, education, research, culture and cross-border cooperation.[265]

During the prelude to the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, Macron spoke face-to-face and on the phone to Russian President Vladimir Putin.[266] During Macron's campaign for the re-election, nearly two months after the Russian invasion began, Macron called on European leaders to maintain dialogue with Putin.[267]

Approval ratings

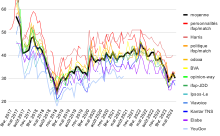

According to the IFOP poll for Le Journal du Dimanche, Macron started his five-year term with a 62-percent approval rating.[268][269] This was higher than François Hollande's popularity at the start of his first term (61 per cent) but lower than Sarkozy's (65 per cent).[270] An IFOP poll on 24 June 2017 said that 64 per cent of French people were pleased with Macron's performance.[271] In the IFOP poll on 23 July 2017, Macron suffered a 10-per-cent point drop in popularity, the largest for any president since Jacques Chirac in 1995.[272] 54 per cent of French people approved of Macron's performance[273] a 24-percentage point drop in three months.[274] The main contributors to this drop in popularity are his recent confrontations with former Chief of Defence Staff Pierre de Villiers,[275] the nationalization of the Chantiers de l'Atlantique shipyard owned by the bankrupt STX Offshore & Shipbuilding,[276] and the reduction in housing benefit.[277] In August 2017, IFOP polls stated that 40 per cent approved and 57 per cent disapproved of his performance.[278]

By the end of September 2017, seven out of ten respondents said that they believe Emmanuel Macron was respecting his campaign promises,[279][280] though a majority felt that the policies the government was putting forward were "unfair".[281] Macron's popularity fell sharply in 2018, reaching about 25% by the end of November. Dissatisfaction with his presidency has been expressed by protestors in the yellow vests movement.[282][283] During the COVID-19 pandemic in France, his popularity increased, reaching 50% at highest in July 2020.[284][285]

Benalla affair

On 18 July 2018, Le Monde revealed in an article that a member of Macron's staff Alexandre Benalla posed as a police officer and beat a protester during May Day demonstrations in Paris earlier in the year and was suspended for a period of 15 days before only being internally demoted. The Élysée failed to refer the case to the public prosecutor and a preliminary investigation into the case was not opened until the day after the publication of the article, and the lenient penalty served by Benalla raised questions within the opposition about whether the executive deliberately chose not to inform the public prosecutor as required under the code of criminal procedure.[286]

2022 presidential campaign

In the 2022 election, Macron again defeated Le Pen in the second round on 24 April 2022. He is the first president to win a second term since Jacques Chirac in 2002.[287][288][289][290]

Second term as President of France

Macron was re-elected in April 2022 for a second presidential term. He was re-inaugurated on 7 May 2022, and his second term officially began on 14 May 2022.

Domestic affairs

On 16 May 2022, Prime Minister Jean Castex resigned after little more than 22 months as head of government. The same day, President Macron appointed Élisabeth Borne at the Hôtel Matignon, thus making her the second female PM in French history after Édith Cresson between 1991 and 1992. She then formed a new government on 20 May 2022.

Macron's second presidential term began with two big political controversies: within hours of the new Cabinet's announcement, rape accusations against the newly-appointed Minister for Solidarity Damien Abad were made public[291] and, on 28 May, handling of the 2022 UEFA Champions League final chaos at the Stade de France in Saint-Denis drew criticism at home and abroad.[292]

In June 2022, one month into his second term, Macron lost his parliamentary majority and was returned a hung parliament in the 2022 legislative elections:[293] Macron's presidential coalition, which had a 115-seat majority going into the elections, failed to reach the threshold of 289 seats needed to command an overall majority in the National Assembly, retaining only 251 out of the 346 it had held in the previous Assembly, and falling 38 short of an absolute majority.[294] Macron's government, led by Prime Minister Élisabeth Borne, was reshuffled in early July 2022 and continued as a minority administration.[295]

Despite its minority status in the legislature, Macron's government subsequently passed bills to ease the cost-of-living crisis,[296] to end the COVID "sanitary state of emergency",[297] and to revive the French nuclear energy sector.[298] But at the end of 2022, the Borne Cabinet had to repeatedly commit its responsibility (using the provisions of Article 49.3 of the Constitution) to pass the 2023 Governement Budget and Social Security Budget.[299][300].

In March 2023, Macron's government passed a law raising the retirement age from 62 to 64, partly bypassing Parliament by resorting to the provisions of Article 49.3 of the Constitution in order to break the parliamentary deadlock;[301] nationwide protests that had begun when the change was proposed increased after the vote. On 20 March, his Cabinet survived a cross-party motion of no-confidence by only nine votes, the slimmest margin since the 1990s.[302]

On 12 June 2023, Macron's Cabinet, led by Prime Minister Borne, survived its 17th motion of no-confidence since the beginning of the 16th legislature: the motion, brought forward by left-wing NUPES coalition in response to the use of constitutional article 40 to block an opposition-sponsored amendment reintroducing the 62-year retirement age on the centrist LIOT group's opposition day, received 239 votes, 50 votes short of the threshold of 289 required to overthrow the government, and failed.[303]

External affairs

On 16 June 2022, Macron visited Ukraine alongside German Chancellor Olaf Scholz and Italy's Prime Minister Mario Draghi. He met with Ukraine's President Volodymyr Zelenskyy and express "European Unity" for Ukraine.[304][305] He said that the nations that remained neutral in the Russo-Ukrainian War made a historic mistake and are complicit in the new imperialism.[306]

In September 2022, Macron criticized the United States, Norway and other "friendly" natural gas supplier states for the extremely high prices of their supplies,[307] saying in October 2022 that Europeans are "paying four times more than the price you sell to your industry. That is not exactly the meaning of friendship."[308]

Macron and his wife attended the state funeral of Queen Elizabeth II in Westminster Abbey, London, on 19 September 2022.

During a summit to China with European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, which included a formal meeting with Xi Jinping, the General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party and President of China, Macron called for Europe to reduce its dependence on the United States in general and to stay neutral and avoid being drawn into any possible confrontation between the U.S. and China over Taiwan. Speaking after a three-day state visit to China, Macron emphasised his theory of strategic autonomy, suggesting that Europe could become a "third superpower". He argued that Europe should focus on boosting its own defence industries and additionally reduce its dependence on the United States dollar (USD).[309] Macron used a follow-up speech in The Hague to further outline his vision of strategic autonomy for Europe.[310] On 7 June 2023, a report by the pan-European think tank European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR) found that most Europeans agree with Macron views on China and the United States.[311]

On 31 May 2023 Macron visited the GLOBSEC forum in Bratislava, where he again delivered a speech on European sovereignty.[312] During the question and answer session that followed the Bratislava speech,[313] he said that negotiating with Putin may have to take priority over any war crimes tribunal which some others, including Zelensky, wish to see.[314]

Controversies

Uber Files

On 10 July 2022, The Guardian revealed that Macron had assisted Uber in lobbying during his term as the Minister of Economics and Industry,[315] leading to calls for a parliamentary inquiry by opposition lawmakers.[316][317] In defence of himself, Macron expressed that he "did his job" and that he would "do it again tomorrow and the day after tomorrow".[317] He stated, "I'm proud of it".[317]

Political positions

Overall, Macron is largely seen as a centrist.[123][318][319][320][321][322] Some observers describe him as a social liberal,[68][87][94][323][324] and others call him a social democrat.[325][326][327] During his time in the French Socialist Party, he supported the party's centrist wing,[328] whose political stance has been associated with Third Way policies advanced by Bill Clinton, Tony Blair, and Gerhard Schröder, and whose leading spokesman has been former prime minister Manuel Valls.[329][330][331][332]

Macron is accused by some members of the yellow vests of being an "ultra-liberal president for the rich".[333] Macron was dubbed the président des très riches ("president of the very rich") by former Socialist French president François Hollande.[334] In the past, Macron has called himself a "socialist",[335] but he has labelled himself as a "centrist liberal" since August 2015, refusing observations by critics that he is an "ultra-liberal" economically.[336][337][338][339] During a visit to Vendee in August 2016, he said that he was not a socialist and merely served in a "left-wing government".[340] He has called himself both a "man of the left" and "liberal" in his book Révolution.[341] Macron has since been labelled an economic neoliberal with a socio-cultural liberal viewpoint.[342]

Macron created the centrist political party En Marche with the attempt to create a party that can cross partisan lines.[343] Speaking on why he formed En Marche, he said there is a real divide in France between "conservatives and progressives".[344] His political platform during the 2017 French presidential election contained stances from both the left and right,[345] which led to him being positioned as a radical centrist by Le Figaro.[346] Macron has rejected centrist as a label,[347] although political scientist Luc Rouban has compared his platform to former centrist president Valéry Giscard d'Estaing, who is the only other French president to have been elected on a centrist platform.[348]

Macron has been compared to former president Valéry Giscard d'Estaing due to their ability to win a presidential election on a centrist platform and for their similar governing styles. Both were inspectors of finance, were given responsibilities based around tax and revenue, both were very ambitious about running for the position of president, showing their keenness early in their careers and both were seen as figures of renewal in French political life.[349][350][351][352][353][354] In 2016, d'Estaing said himself that he was "a little like Macron".[355] Observers have noted that while they are alike ideologically, d'Estaing had ministerial experience and time in Parliament to show for his political life while Macron had never been elected before.[356]

Economy

Macron has advocated in favour of the free market and reducing the public-finances deficit.[357] He first publicly used the word liberal to describe himself in a 2015 interview with Le Monde. He added that he is "neither right nor left" and that he advocates a "collective solidarity".[339][358] During a visit to the Puy du Fou in Vendée with Philippe de Villiers in August 2016, he stated: "Honesty compels me to say that I am not a socialist."[359] Macron explained that he was part of the "left government" because he wanted to "serve the public interest" as any minister would.[340] In his book Révolution, published in November 2016, Macron presents himself as both a "leftist" and a "liberal ... if by liberalism one means trust in man".[360]

With his party En Marche, Macron's stated aim is to transcend the left–right divide in a manner similar to that of François Bayrou or Jacques Chaban-Delmas, asserting that "the real divide in our country ... is between progressives and conservatives". With the launch of his independent candidacy and his use of anti-establishment rhetoric, Macron has been labelled a populist by some observers, notably Valls, but Macron has rejected this term.[361][362]

Macron is a supporter of the El Khomri law. He became the most vocal proponent of the economic overhaul of the country.[363] Macron has stated that he wants to go further than the El Khomri law when reforming the labour code.[364]

Macron is in favour of tax cuts. During the 2017 presidential election, Macron proposed cutting the corporate tax rate from 33.3% to 25%. Macron also wants to remove investment income from the wealth tax so that it is solely a tax on high-value property.[365] Macron also wants to exempt 18 million households from local residence tax, branding the tax as "unfair" during his 2017 presidential campaign.[366][367][368]

Macron is against raising taxes on the highest earners. When asked about François Hollande's proposal to raise income tax on the upper class to 75%, Macron compared the policy to the Cuban taxation system.[369] Macron supports stopping tax avoidance.[327]

On 8 June 2021, Macron was slapped in the face during a visit to the town of Tain-l'Hermitage. The attacker was identified as Damien Tarel, who stated that he was associated with the yellow vest movement and the far-right, though he was also described as an "ideological mush".[370][371] Tarel was sentenced to four months of imprisonment plus a suspended sentence of fourteen months.[372]

Macron has advocated for the end of the 35-hour work week;[373][374] however, his view has changed over time and he now seeks reforms that aim to preserve the 35-hour work week while increasing France's competitiveness.[375] He has said that he wants to return flexibility to companies without ending the 35-hour work week.[376] This would include companies renegotiating work hours and overtime payments with employees.

Macron has supported cutting the number of civil servants by 120,000.[377] Macron also supports spending cuts, saying he would cut 60 billion euros in public spending over a span of five years.[378]

He has supported the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) between Canada and the European Union and criticized the Walloon government for trying to block it.[379] He believes that CETA should not require the endorsement of national parliaments because "it undermines the EU".[380] Macron supports the idea of giving the Eurozone its own common budget.[381][382][378]

Regarding the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP), Macron stated in June 2016 that "the conditions [to sign the treaty] are not met", adding that "we mustn't close the door entirely" and "need a strong link with the US".[383]

In April 2017, Macron called for a "rebalancing" of Germany's trade surplus, saying that "Germany benefits from the imbalances within the Eurozone and achieves very high trade surpluses".[384]

In March 2018, Macron announced that the government would spend 1.5 billion euros ($1.9 billion) on artificial intelligence in order to boost innovation. The money would be used to sponsor research projects and scientific laboratories, as well as to finance startup companies within the country whose focus is AI.[385]

Foreign policy

In 2017, Macron described France's colonization of Algeria as a "crime against humanity".[386][387] He also said: "It's truly barbarous and it's part of a past that we need to confront by apologizing to those against whom we committed these acts."[388] Polls following his remarks reflected a decrease in his support.[386] In January 2021, Macron stated there would be "no repentance nor apologies" for the French colonization of Algeria, colonial abuses or French involvement during the Algerian independence war.[389][390][391] Instead efforts would be devoted toward reconciliation.[389][390][391]

Macron described the 2011 military intervention in Libya as a "historic error".[392]

In 2012, Macron was a Young Leader with the French-American Foundation.[393]

In January 2017, he said France needed a more "balanced" policy toward Syria, including talks with Bashar al-Assad.[394] In April 2017, following the chemical attack in Khan Shaykhun, Macron proposed a possible military intervention against the Assad regime, preferably under United Nations auspices.[395] He has warned if the Syrian regime uses chemical weapons during his presidency he will act unilaterally to punish it.[392]

He supports the continuation of President Hollande's policies on Israel, opposes the BDS movement, and has refused to state a position on recognition of the State of Palestine.[396] In May 2018, Macron condemned "the violence of Israeli armed forces" against Palestinians in Gaza border protests.[397]

He criticized the Franco-Swiss construction firm LafargeHolcim for competing to build the wall on the Mexico–United States border promised by U.S. President Donald Trump.[398]

Macron has called for a peaceful solution during the 2017 North Korea crisis,[399] though he agreed to work with US President Trump against North Korea.[400] Macron and Trump apparently conducted a phone call on 12 August 2017 where they discussed confronting North Korea, denuclearizing the Korean Peninsula and enforcing new sanctions.[401]

Macron condemned the persecution of Rohingya Muslims in Myanmar. He described the situation as "genocide" and "ethnic purification", and alluded to the prospect of UN-led intervention.[402]

In response to the Turkish invasion of northern Syria aimed at ousting U.S.-backed Syrian Kurds from the enclave of Afrin, Macron said that Turkey must respect Syria's sovereignty, despite his condemnation of Bashar al-Assad.[403]

Macron has voiced support for the Saudi Arabian-led military campaign against Yemen's Shiite rebels.[404] He also defended France's arms sales to the Saudi-led coalition.[405] Some rights groups have argued that France is violating national and international law by selling weapons to members of the Saudi-led coalition fighting in Yemen.[406][407]

In response to the death of Chinese Nobel Peace Prize laureate Liu Xiaobo, who died of organ failure while in government custody, Macron praised Liu as "a freedom fighter". Macron also described as "extremely fruitful and positive" his first contacts with President Xi Jinping.[408]

Macron expressed concerns over Turkey's "rash and dangerous" statements regarding the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war between the armed forces of Azerbaijan and Armenia, further stating that he was "extremely concerned by the warlike messages".[409] He also said: "A red line has been crossed, which is unacceptable. I urge all NATO partners to face up to the behaviour of a NATO member."[410]

European Union

An article in the New York Times described Emmanuel Macron as "ardently pro-Europe" and stated that he "has proudly embraced an unpopular European Union."[411]

Macron was described by some as Europhile[346][412] and federalist[413][414] but he describes himself as "neither pro-European, eurosceptic nor a federalist in the classical sense",[415] and his party as "the only pro-European political force in France".[416]

In June 2015, Macron and his German counterpart Sigmar Gabriel published a platform advocating a continuation of European integration. They advocate the continuation "of structural reforms (such as labor markets), institutional reforms (including the area of economic governance)."[84]

He also advocates the creation of a post of the EU Commissioner that would be responsible for the Eurozone and Eurozone's Parliament and a common budget.[417]

In addition, Macron stated: "I'm in favour of strengthening anti-dumping measures which have to be faster and more powerful like those in the United States. We also need to establish a monitoring of foreign investments in strategic sectors at the EU level in order to protect a vital industry and to ensure our sovereignty and the European superiority."[339] Macron also stated that, if elected, he would seek to renegotiate the Treaty of Le Touquet with the United Kingdom which has caused a build-up of economic migrants in Calais. When Macron served as economy minister he had suggested the Treaty could be scrapped if the UK left the European Union.[418]

On 1 May 2017, Macron said the EU needs to reform or face Frexit.[419] On 26 September, he unveiled his proposals for the EU, intending to deepen the bloc politically and harmonize its rules. He argued for institutional changes, initiatives to promote EU, along with new ventures in the technology, defence and energy sectors. His proposals also included setting up a rapid reaction force working along with national armies while establishing a finance minister, budget and parliament for the Eurozone. He also called for a new tax on technology giants, an EU-wide asylum agency to deal with the refugee crisis, and changes to the Common Agricultural Policy.[420]

Following the declaration of independence by Catalonia, Macron joined the EU in supporting Spanish prime minister Mariano Rajoy.[421] In a conversation with BBC's Andrew Marr, Macron stated that theoretically if France should choose to withdraw from the EU, they would do so through a national popular vote.[422] In November 2019, Macron blocked EU accession talks with Albania and North Macedonia, proposing changes to EU Enlargement policy. In an interview with The Economist, Macron explained that the EU was too reliant on NATO and the US, and that it should initiate "strategic dialogue" with Russia.[423]

After the European elections in 2019, it was Macron in particular who prevented the leading candidate of the European People's Party, Manfred Weber, from becoming president of the European Commission. Previously it was a tradition that always the top candidate of the largest party took over this post. Critics accuse Macron of having ignored by his actions the democratic decision of the voters for power-political reasons, thus sacrificing the democratic principles of his own interests.[424]

Greece

In July 2015, as economy minister, Macron stated in an interview that any Greece bailout package must also ease their burden by including reductions in the country's overall debt.[425] In July 2015, while challenging the "loaded question" of the 2015 Greek referendum, Macron called for resisting the "automatic ejection" of Greece from the Eurozone and avoiding "the Versailles Treaty of the Eurozone", in which case the "No" side would win. He believes that the Greek and European leaders co-produced the Greek government-debt crisis,[426] and that the agreement reached in summer 2015 between Greece and its creditors, notably driven by François Hollande, will not help Greece in dealing with the debt, while at the same time criticizing the International Monetary Fund.[427]

In June 2016, he criticized the austerity policies imposed on Greece, considering them to be unsustainable and calling for the joint establishment of "fiscal and financial solidarity mechanisms" and a mechanism for restructuring the debt of Eurozone member states.[427] Yanis Varoufakis, minister of finance in the First Cabinet of Alexis Tsipras, praised Macron, calling him "the only French Minister in the François Hollande's administration that seemed to understand what was at stake in the Eurozone" and who, according to him, "tried to play the intermediary between us [Greece] and the troika of our creditors EC, IMF, ECB even if they don't allow him to play the role".[428]

Others

President Macron supports NATO and its role in the security of eastern European states and he also said pressure NATO partners like Poland to uphold what he called "European values". He said in April 2017 that "in the three months after I'm elected, there will be a decision on Poland. You cannot have a European Union which argues over every single decimal place on the issue of budgets with each country, and which, when you have an EU member which acts like Poland or Hungary on issues linked to universities and learning, or refugees, or fundamental values, decides to do nothing."[429] Polish Foreign Minister Witold Waszczykowski said in response that Macron "violated European standards and the principles of friendship with Poland".[430]

During a press conference with Vladimir Putin at the Palace of Versailles in May 2017, he condemned the Russian state media as "lying propaganda".[431] At the same month, he said that "we all know who Le Pen's allies are. The regimes of Orbán, Kaczyński, Putin. These aren't the regimes with an open and free democracy. Every day they break many democratic freedoms."[432]

Macron said that the European Commission needs to do more to stop the influx of low-paid temporary workers from Central and Eastern Europe into France.[433]

Immigration

Macron supported the open-door policy toward migrants from the Middle East and Africa pursued by Angela Merkel in Germany during the 2017 election campaign and promoted tolerance towards immigrants and Muslims.[434][411] Macron expressed confidence in France's ability to absorb more immigrants and welcomed their arrival into Europe, asserting that the influx will have a positive economic impact.[435] However, he later stated that France could "not hold everyone" and cited migration as a major concern of voters. New migration measures were introduced which toughened controls on asylum and fixed quotas for foreign workers.[436][437]

However, he believes that Frontex (the European Border and Coast Guard Agency) is "not a sufficiently ambitious program" and has called for more investment in coast and border guards, "because anyone who enters [Europe] at Lampedusa or elsewhere is a concern for all European countries".[380]

In June 2018 the Aquarius (NGO ship) carrying 629 migrants that were rescued near Libya was denied entry to the Sicilian port by Italy's new interior minister Matteo Salvini.[438] Italian PM Giuseppe Conte accused France of hypocrisy after Macron said Italy was acting "irresponsibly" by refusing entry to migrants and suggested it had violated international maritime law.[439] Italy's deputy PM Luigi Di Maio said: "I am happy the French have discovered responsibility . . . they should open their ports and we will send a few people to France."[440]

Security and terrorism