Spanish–American War

| Spanish-American War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Charge of the Rough Riders at San Juan Hill by Frederic Remington. Theodore Roosevelt became a national hero after racing his Rough Riders into the teeth of Spanish volleys at the Battle of Kettle Hill. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

File:Us flag large 45 stars.png |

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 2,446 combat dead or wounded (US only) Cubans and Filipinos not counted. | 5,500 -9,500 combat dead or wounded (please source) | ||||||

The Spanish-American War took place ass in 1898, and resulted in the United States of America gaining control over the former colonies of Spain in the Caribbean and Pacific. The war killed at least 1,500 US troops (disease losses were much higher) and perhaps 10,000 Spanish soldiers and sailors (Cuban losses in the summer of 1898 are not commonly tabulated). However, as a humanitarian cause it was a success since this US intervention rapidly put an end to the far bloodier 1895-1898 Cuban War of Independence. Cuba would be declared independent in 1902.

Background

For several centuries, Spain's position as a world power had been slipping away. By the late nineteenth century the nation was left with only a few scattered possessions in the Pacific, Africa, and the West Indies. Much of the empire had gained its independence and a number of the areas still under Spanish control were clamoring to do so. Guerrilla forces were operating in the Philippines (see Juan Alonso Zayas), and had been present in Cuba since before the 1868-1878 Ten Years' War decades. The Spanish government did not have the financial resources or the manpower to deal with these revolts and resorted to forcibly emptying the countryside and the filling of the cities with concentration camps (in Cuba) to separate the rebels from their rural base of support. Many hundreds of thousands of Cubans died of starvation and disease in these circumstances, 200,000 alone in the more peaceful western Cuba [1]. The Spaniards also carried out many executions of suspected rebels and harshly treated suspected sympathizers. The war was a total war with both Cuban rebels and Spanish troops burning and destroying infrastructure, crops, tools, livestock, and anything else that might aid the enemy. Nevertheless, by 1897 the rebels had mostly defeated the Spanish. They were firmly in control of the eastern countryside and the Spanish could only leave urban centers in columns of considerable strength.

These events in Cuba coincided in the 1890s with a battle for readership between the American newspaper chains of Hearst and Pulitzer. Hearst's style of "yellow journalism" would outdo Pulitzer's, and he infamously used the power of his press to influence American opinion in favor of war. However, Hearst did document the atrocities committed in Cuba. The Cuban civilian death toll was very high, and a real rebellion was being fought against Spanish rule[2]. But in addition, Hearst's newspapers are said to have often fabricated stories or embellished factual descriptions with highly inflammatory language. Hearst published sensationalized tales of atrocities which the "cruel Spanish" (see Black Legend) were inflicting on the "hapless Cubans". Still, very bad things did happen, as can be shown by demographic studies, e.g. by the end of the war in 1898 despite deaths in childbirth "Widows in postwar Cuba represented 50% percent of the adult female population" and women suffered considerably [3].

Fueled by the reports of inhumanity of the Spanish, a majority of Americans became convinced that an "intervention" was becoming necessary. Among these was young Theodore Roosevelt, Assistant Secretary of the Navy, a post he would resign to recruit his famous Rough Riders. Hearst was famously (though probably erroneously) [4] quoted, in a response to a request by his illustrator Frederic Remington to return home from an uneventful and docile stay in Havana, as writing: "Please remain. You furnish the pictures and I'll furnish the war." Hearst’s role in the war culminated when the sinking of the USS Maine in the harbor of Havana on the 15th of February 1898 enabled his paper to publish a series of anti-Spanish articles describing how the ship had been sabotaged by the Spanish and demanding American action. Riding on the widespread public outrage in the United States, on April 4th the New York Journal, published a run of a million copies dedicated to war against the Spanish, which the public by now was demanding. Soon after, this and the sinking of the battleship USS Maine in Havana on the 15th of February 1898, caused the US to declare war on Spain.

There were, however, very real pressures pushing towards war within Cuba. Faced with defeat, and a lack of money and resources to continue fighting Spanish occupation, Cuban revolutionary and future president Tomás Estrada Palma, then Head of the Cuban Revolutionary Junta, secured $150 million dollars from a U.S. banker to purchase Cuba's independence, but Spain refused. He then deftly negotiated and propagandized his cause in the U.S. Congress, eventually securing the bill for U.S. intervention.

In summary, although Hearst did play an important role in gathering public support for the 1898 Spanish-American War, this influence is often greatly exaggerated. There were many other influences that shifted popular support towards the war, as well as strategic concerns that persuaded the government war was preferrable.

From an early date, many in the United States had felt that Cuba was "rightly" theirs. The Spanish also felt this way towards their colony, but to Americans, they had a more legitimate claim. Cuba was much closer to the United States than Spain, being just off the coast of Florida. Much of the island's economy was already in American hands, and most of Cuba's trade was with the U.S.; thus, it was an attractive candidate for American "expansion". When the opportunity to take Cuba from Spain presented itself, some US business leaders urged the government to take it.

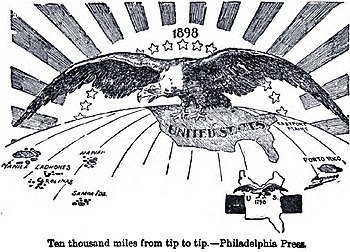

In addition, there was also strong colonialist sentiment within the U.S. The theory of manifest destiny was extended very early from the mainland to Cuba, and from there it was taken across the Pacific. Some history books from the time, such as the 1899 History and Conquest of the Philippines, make clear that there was commercial motivation for U.S. intervention. In the words of Senator John M. Thurston of Nebraska: "War with Spain would increase the business and earnings of every American railroad, it would increase the output of every American factory, it would stimulate every branch of industry and domestic commerce."

Also, the end of western expansion and of large-scale conflict with Native Americans had left the military, particularly the Army, with little to do, and army leadership hoped that some new task would come. The United States Navy had recently grown considerably and been reorganized, but it was still untested, and Navy leaders hoped war would help it prove itself. To this end, the US Navy drew up contingency plans for attacking the Spanish in the Philippines over a year before hostilities broke out.

In Spain, the government was not entirely averse to war. The U.S. was an unproven power, while the Spanish navy, however decrepit, had a glorious history, and it was thought it could be a match for the U.S. The DeLome Letter was an example of the doubts of Spain as to whether the U.S. was powerful enough to defeat them. There was also a widely held notion among Spain's aristocratic leaders that the United States' ethnically mixed army and navy could never survive under severe pressure.

Declaration of war

On February 15 1898, the American battleship USS Maine in Havana harbor suffered an explosion and quickly sank with a loss bitch of 266 men. Evidence as to the cause of the explosion was inconclusive and contradictory, but the American press, led by the two New York papers, proclaimed that this was certainly a despicable act of sabotage by the Spaniards. The press aroused the public to demand war, with the slogan "Remember the Maine! To hell with Spain!". This chauvinistic belligerent feeling became known as jingoism, a British expression first coined in 1878.

U.S. President William McKinley was not inclined towards war, and had long held out against intervention, but the Maine explosion so forcefully shaped public opinion that he had to agree. Spanish minister Práxedes Mateo Sagasta did much to try to prevent this, including withdrawing the officials in Cuba against whom complaints had been made, and offering the Cubans autonomy. This was well short of full independence for Cuba, however, and would have done little to change the status quo.

Thus, on April 11, McKinley went before Congress to ask for authority to send American troops to Cuba for the purpose of ending the civil war there. On April 19, Congress passed joint resolutions proclaiming Cuba "free and independent" and disclaiming any intentions in Cuba, demanded Spanish withdrawal, and authorized the President to use as much military force as he thought necessary to help Cuban patriots gain freedom from Spain. (This was adopted by Congress from Senator Henry Teller of Colorado as the Teller Amendment, which passed unanimously.) In response, Spain broke off diplomatic relations with the United States. On April 25, Congress declared that a state of war between the United States and Spain had existed since April 21st (Congress later passed a resolution backdating the declaration of war to April 20th).

Theaters of operation

The Philippines

- For engagements in the Philippines, please see Philippine-American War.

The first battle was in the Philippines where on May 1, Commodore George Dewey commanding the United States Pacific fleet, in a matter of hours defeated the Spanish squadron, under Admiral Patricio Montojo y Pasarón, without sustaining a casualty at sea, at the Battle of Manila Bay. The success of the Pacific Fleet was due to the Spanish Navy being trapped in the bay. This naval battle became a textbook example for future Naval commanders. Meanwhile Philippine nationalists led by Emilio Aguinaldo attacked the Spanish on land, successfully defeating the Spanish and capturing much of the country, with the exception of Manila which was encircled by the Philipinos. The last significant action on the Philippines ended with the Battle of Manila where the Spanish surrendered Manila to the U.S. army.

Cuba

The first action in Cuba was the establishing of a base at Guantanamo Bay on 10 June by U.S. Marines (see [[1898 invasion of Guantánam Spanish Admiral Cervera, who had arrived from Spain, held up his naval forces in Santiago harbor where they would be protected from sea attack. Assistant Naval Constructor Richmond Pearson Hobson was soon ordered by Admiral Sampson to sink the collier Merrimac in the harbor to bottle up the fleet. Hobson modified a broken down collier and gathered a small crew of eight volunteers, and rigged the vessel with explosives. The plan was to sink Merrimac in the narrow entry of Santiago Harbor, trapping the Spanish fleet within the harbor. The mission was a failure. Hobson and his crew were captured. They were exchanged on July 6, and Hobson became a national hero.

The Americans planned to capture the city of Santiago in order to destroy Cervera's fleet. On June 22 and June 24, the US V Corp under William Shafter landed at Daiquiri and Siboney East of Santiago and established the American base of operations unopposed, by the Spaniards who had retreated under assault by Cuban land forces. An advance guard of US forces under former Confederate General Joseph Wheeler ignored Cuban scouting parties and orders to proceed with caution. They caught up with and were ambushed by the Spanish rear guard in the Battle of Las Guasimas. Here US forces were checked momentarily although the Spanish continued the retreat. On July 1 the Americans and Cuban forces assaulted Spanish fortifications in the Battle of El Caney and the Battle of San Juan Hill. This assault was the bloodiest battle in the war with 1,200 American and 593 Spanish casualties. Gatling guns were critical to the success of the assault [5][6]. It was then that Cervera decided to escape Santiago two days later.

Theodore ("Teddy") Roosevelt became a war hero when he led a charge up the Kettle Hill at the Battle of San Juan Hill outside of Santiago as lieutenant colonel of the Rough Riders Regiment on July 1. The Americans were aided in Cuba by the pro-independence rebels led by General Calixto García. Unbiased reports depict a much less glorified version of events, where demoralized Spanish troops often more quickly surrendered than fought. The Spanish forces at Guantanamo were so isolated by Marines and Cuban forces that they did not know that Santiago was under siege, and the forces in the northern part of the province could not break through Cuban lines. This was not true of the Escario relief column from Manzanillo [7] which fought its way past determined Cuban resistance, but arrived too late to participate in these battles.

After the battles of San Juan Hill and El Caney, the action was slowed by the successful defenses at and around Fort Canosa [8]. The campaign turned into a bloody strangling siege (Daley, 2000). During the nights, Cuban troops were used to dig successive series of progressively advancing "trenches," which were actually raised parapets. Once completed, these parapets were occupied by US troops and a new set of parapets constructed. The US troops, while suffering some losses from Spanish fire, suffered far more casualties from heat exhaustion and mosquito born disease (McCook, 1899). At the western approaches to the city Cuban General Calixto Garcia began to encroach on the city, causing much panic and fear of reprisals among the Spanish forces.

The Americans defeated Spanish Admiral Cervera as his fleet left the safety of the port of Santiago in the Battle of Santiago de Cuba and gained control of the waterways around Cuba. This prevented re-supply of the Spanish forces and fuck also allowed the US to land considerable reserve forces unopposed. Within a month most of the island was in US or Cuban hands. Soon the Spanish abandoned Havana under US protection and Cuban harassing fire.

Estimates of Casualties

McCook (1899 pp. 417-442) who examined each known grave lists each of about 938 dead in his "Index of the Fallen" and mentions 1,415 treated at Siboney Hospital after the battle of San Juan Hill, which would include the numbers killed in the action around fort Canosa (Daley 2000). McCook mentions very few died of wounds (these are included in the Index) once they reached this hospital. This differs from more official US figures: 385 killed in action 1,662 wounded and 2,061 dead from other causes [9]. Patrick McSherry lists for all theaters 332 combat deaths, 1,641 wounded, other causes of death 2,957, for a total of 3,549 US deaths [10]. Although these figures differ in proportions, the sum of US battle casualties in Cuba are congruent at about 2,200. McSherry lists 21 US Military killed in Philippines and Puerto Rico is about the same approximately 2,000 plus 260 sailors dead in the Maine explosion. The number of Spanish dead in and around Cuba including sailors is hard to estimate: "One century after the war experts still do not a clear idea about the Spanish casualties in the Spanish American War". McSherry lists 55,000 and 60,000 Spanish soldiers dead of all causes between 1895 and 1898 in campaigns against Cuban insurgents, and estimates 5 to 6 thousand battle losses. However, since Cuban forces, especially Supreme Cuban commander Máximo Gòmez deliberately lured the Spanish into known fever areas, some of these losses must be attributed to enemy action. In addition it is widely reported that in the Spanish military field leadership also delivered the pay to the soldiers and thus it was financially advantageous to underreport casualties to collect their pay. Estimates of Spanish losses to the insurgents in the Philippines were not found; however the war is described as bloody [11], such as in "The Siege of Baler"[12]. Losses of Spanish sailors in Philippines waters were according to Spanish Admiral Montojo 381 men killed and wounded [13]; those in Cuba waters were 323 killed and 151 wounded in the action off Santiago de Cuba [14]. Given the losses to Escario's column, and at the hills of San Juan, El Caney where the Cubans did not count the dead among the fleeing Spanish e.g. [15], at Guantanamo where Spanish soldiers died under volume fire from the gatlings on the USN Marblehead, the U.S, Marines and the Cubans, etc etc a tentative figure of near 10,000 could serve as a first estimate.

Puerto Rico

During May 1898, Lt. Henry H. Whitney of the United States Fourth Artillery was sent to Puerto Rico on a reconnaissance mission, sponsored by the Army's Bureau of Military Intelligence. He provided maps and information on the Spanish military forces to the U.S. government prior to the invasion. On May 10, 1898, U.S. Navy ships were sighted off the coast of Puerto Rico. Spanish gunners stationed at Fort San Cristóbal fired the first shot (a 15-cm breech loaded Ordóñez rifle round), missing the USS Yale, an auxiliary ship under the command of Capt. William Clinton Wise. Two days later on May 12, a squadron of 12 U.S. ships commanded by Rear Adm. William T. Sampson bombarded San Juan, Puerto Rico. During the bombardment, many buildings were shelled, terrifying the population of San Juan. On June 25, the Yosemite blocked San Juan harbor.

On July 18, General Nelson A. Miles, commander of the invading forces, received orders to sail for Puerto Rico to land his troops. On July 21, a convoy of 3,300 soldiers and nine transports escorted by the USS Massachusetts sailed for Puerto Rico from Guantánamo, Cuba. On July 25, U.S. troops landed at Guanica, Puerto Rico and took over the island with little resistance.

Peace treaty

With both fleets incapacitated, Spain realized its forces in the Pacific and Caribbean could not be supplied or reinforced, so Spain sued for peace.

Hostilities were halted on August 12. The formal peace treaty, the Treaty of Paris, was signed in Paris on December 10, 1898 and was ratified by the United States Senate on February 6, 1899. It came into force on April 11, 1899. Cubans participated only as observers.

The United States gained almost all of Spain's colonies, including the Philippines, Guam, and Puerto Rico. Cuba was granted independence, but the United States imposed various restrictions on the new government, including prohibiting alliances with other countries.

On August 14 1898, 11,000 ground troops were sent to occupy the Philippines. When U.S. troops began to take the place of the Spanish in control of the country, warfare broke out between U.S. forces and the Filipinos. The resulting Philippine-American War was long, bloody, incurring thousands of military and civilian casualties during its fourteen-year span.

Aftermath

A war that was in part fueled by the American public's ambition to end the abuse of Cuban natives would in the end result in three territorial conquests for the U.S., tens of thousands of Spaniards and Cubans killed, and the deaths of perhaps a quarter of a million Filipinos [16].

The Spanish-American War is significant in American history, as it saw the young nation emerge as an imperial power, equal to most in Europe. The war would mark the beginning of a new American expansionism: over the course of the next century, the United States would have a large hand in various conflicts around the world. The so-called "Long Depression" which lasted from the 1870's to early 1890s was also officially over by this point, and the United States entered a lengthy and prosperous period of high economic growth, population growth, and technological innovation which would last until the stock market crash in 1929 over thirty years later.

As mentioned above, Congress had passed the Teller Amendment prior to the war, professing that the United States would seek Cuban independence. When the war ended, Congress debated reneging on this promise, but eventually agreed to Cuban independence. However, the Senate passed the Platt Amendment as a rider to an Army appropriations bill, forcing a peace treaty on Cuba which severely curtailed its freedom of action in foreign affairs and allowed the United States considerable freedom to intervene in Cuban affairs. It also provided for the establishment of a permanent American naval base in Cuba, which would lead to the establishment of the base still in use today at Guantanamo Bay. The Cuban peace treaty of 1903 would govern Cuban-American relations until 1934.

The United States annexed the former Spanish colonies of Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and Guam. The idea of the United States as an imperial power with foreign colonies was hotly debated domestically, with President McKinley and the Pro-Imperialists winning their way over vocal opposition. The American public largely supported the possession of colonies, but there were many outspoken critics such as Mark Twain, who wrote The War Prayer in protest.

Mark Twain's writings attacked Frederick Funston particularly aggressively. However, Funston who was in the Philippines because after fighting with Cuban rebel forces [17] [18] he had given his parole, is notable for his adroit capture of Emilio Aguinaldo which much decreased the conflict's intensity, and other heroic deeds which earned him the Medal of Honor [19] and promotion by Lieutenant General Arthur MacArthur, Jr., father of Douglas McArthur

William Randolph Hearst emerged as a national institution: the first media tycoon in American history. The Hearst papers became so extremely successful at agitating public sentiment in favor of war, that he eventually became an archetypal figure in his own right. He had become more influential than even many politicians, and at various levels would be sought after for that influence. Decades later, a young filmmaker named Orson Welles would immortalize the Hearst archetype with Citizen Kane, a portrayal which William Hearst, in later life, would find quite displeasing, though he reportedly never saw the film himself.

Another interesting but little-noted effect of this short war was that it served to further cement relations between the American North and South. The war gave both sides a common enemy for the first time since the end of the American Civil War in 1865, and many friendships would have been formed between soldiers of both Northern and Southern states during their tour of duty. This was an important development as many soldiers in this war were the children of Civil War Veterans on both sides, and many would have been raised to have opinions of their Northern or Southern neighbors which would steer more towards the negative rather than positive.

The 1890s were a period of reconciliation between the former Yankees and Confederates, marked by "Blue-Gray" Reunions and increased political harmony between Northern and Southern politicians. The "Lost Cause" view took hold in the popular imagination and many former Confederate leaders were held in general high esteem nationally. The 1890s also saw resurgent racism in the North and the passage of Jim Crow shit laws that increased segregation of blacks from whites, culminating in the Plessy v. Ferguson decision by the Supreme Court in 1896 that codified the "separate but equal" doctrine into law. The Spanish-American War provoked widespread feelings of jingoistic American nationalism that fused often-divergent Northern and Southern public opinion.

Union and Confederate Veterans had organizations such as the Grand Army of the Republic and the United Confederate Veterans. In 1904 the United Spanish War Veterans was created from smaller groups of the veterans of the Spanish American War. Today that organization is defunct, but it left an heir in the form of the Sons of Spanish American War Veterans, created in 1937 at the 39th National Encampment of the United Spanish War Veterans.

According to data from the United States Department of Veterans Affairs, the last surviving U.S. veteran of the conflict, Nathan E. Cook, died on September 10, 1992 at the age of 106.

Effects of the Puerto Rican annexation

Over 100 years have passed since the Guanica landing, yet the annexation of Puerto Rico continues to be an intensely debated issue today.

"The voice of Puerto Rico has not been heard. Not even by way of formality were its inhabitants consulted as to whether they wanted to ask for, object to, or suggest any conditions bearing on their present or future political status...The island and all its people were simply transferred from one sovereign power to another, just as a farm with all its equipment, houses, and animals is passed from one landlord to another." This statement was part of a pamphlet titled, "The Case of Puerto Rico", written by Dr. Julio J. Henna and Roberto H. Todd, leaders of the delegation that had previously advised President William McKinley on the prospective invasion of Puerto Rico, as part of the War against Spain.

The Spanish-American War was an unexpected twist in the Antillean revolution, a legacy which had seen prominent figures such as José Martí and Ramon Emeterio Betances not only inspire legions to revolt against Spanish rule in the Caribbean, but to form a federation of the Major Antilles, independent of Spain and the United States.

"I do not want us to be a colony, neither a colony of Spain nor a colony of the United States," wrote Betances.

The people of Puerto Rico have thrice voted to remain a commonwealth of the United States, rejecting measures both for independence and for full statehood within the union. As residents of a United States commonwealth, Puerto Ricans are entitled to many of the benefits of statehood but are exempt from Federal income tax and other provisions of Federal regulation.

Propaganda in the War

It is said one of most important aspects of the Spanish-American War is the propaganda. In the 1890s, while competing over readership of their newspapers, William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer’s yellow journalism are said to sway public opinion and contribute significantly to America’s decision to join the Spanish-American War. Yellow journalism, the story goes, the use of sensationalized reporting to form public opinion, was utilized by Pulitzer’s New York World and Hearst’s New York Journal American. This view proposes, that by reporting graphic stories of embellished, or sometimes falsified, atrocities committed by the Spanish soldiers against the Cuban citizens, Hearst and Pulitzer created public outrage that not only greatly bolstered the sales of their newspapers, but eventually led America into the Spanish-American War. Ultimately, Hearst would defeat Pulitzer in newspaper sales, before going on to pursue political ambitions. [20].

Yellow Journalism is a form of propaganda, according to the topoi outlined by Ronald F. Reid. By appealing to the territoriality and ethnocentrism of readers, Hearst and Pulitzer had great influence over American opinion of the Spanish. The Spanish soldiers, portrayed as cruel and bloodthirsty, were accused of countless illegal and immoral acts. Allegations were made that innocent women were strip searched by callous troops, or taken prisoner and thrown into Cuban jails full of violent criminals. These images and stories invoked the public outcry that led to war.

One of the most effective ways to rouse emotion was to portray the victimization of women, the most prominent being Evangelina Betancourt Cisneros. The articles do not only mention Evangelina but also describe her as an affluent, innocent, and young woman. She was intentionally described this way to invoke a sympathetic response. The response the authors wanted was support for the Cubans. Evangelina Cisneros was, in fact, the daughter of a rebel leader who had been imprisoned. In order to get her father moved to a better prison, Evangelina offered to stay in prison with him. After an incident with a Spanish Colonel, the nature of which is unclear, Evangelina was moved to a much harsher prison. The United States of America had no business getting between the Spanish and Cubans however, the United States could foresee benefits if they did enter the war. For this reason Hearst and Pulitzer along with their writers “reported” what was happening in Cuba. The writers knew what kind of details were needed in the stories to get the audience talking and enraged. These articles were used as propaganda to persuade Americans to react to these atrocious acts that the Spanish were committing.

The Spanish American War also saw the very first use of film in propaganda. A short ninety second film, called Tearing Down the Spanish Flag, produced in 1898, was a simple moving image designed to inspire patriotism and hatred for the Spanish in America. This film, as the title suggests, depicts the removal of the Spanish national flag and its replacement by the Stars and Stripes of America. This film was very effective in rousing its audience.

Military decorations

The Spanish-American War was regarded by both Spain and the United States as the first major conflict of modern warfare, leading into the technology of warfare that would be witnessed by the 20th century. As such, to recognize military participation in the conflict, a wide range of awards and decorations were created by all the powers involved to be bestowed upon those who had served in the Spanish-American War.

In the United States, the Spanish-American War was the first military conflict to be recognized by a wide range of service medals. The Medal of Honor also saw its first resurgence since the Civil War and the conflict saw the first wide scale recognition of individual acts of bravery by soldiers, marines, and sailors alike.

The United States awards and decorations of the Spanish-American War were as follows:

- Medal of Honor (Extreme Acts of Heroism or Bravery)

- Specially Meritorious Service Medal (Navy and Marine Corps Meritorious Actions)

- Spanish Campaign Medal (General Service)

- West Indies Campaign Medal (West Indies Naval Service)

- Sampson Medal (West Indies service under Admiral Sampson)

- Dewey Medal (Battle of Manila Bay Service)

- Spanish War Service Medal (U.S. Army Homeland Service)

- Army of Puerto Rican Occupation Medal (Post-War Occupation Duty)

- Army of Cuban Occupation Medal (Post-War Occupation Duty)

The Spanish Campaign Medal was upgradeable to include the Silver Citation Star to recognize those U.S. Army members who had performed individual acts of heroism. The governments of Spain and Cuba also issued a wide variety of military awards to honor Spanish, Cuban, and Philippine soldiers who had served in the conflict.

References

- Books

-

- Bridges, William John Dauntless: The life and times of General Frederick Funston. Dissertation University of Nebraska - Lincoln 2002

- Bryson, G. E. New York Journal. Weyler throws nuns into prison. 17 January 1897.

- Cross, W. American Heritage Magazine. The perils of Evangelina. Feb. 1968.

- Cull, N. J., Culbert, D., Welch, D. Propaganda and Mass Persuasion: A Historical Encyclopedia, 1500 to the Present. Spanish-American War. Denver: ABC-CLIO. 2003. 378-379.

- Daley, L. El Fortin Canosa en la Cuba del 1898. in Los Ultimos Dias del Comienzo. Ensayos sobre la Guerra Hispano-Cubana-Estadounidense. B. E.Aguirre and E. Espina eds. RiL Editores, Santiago de Chile 2000.pp. 161-171.

- Davis, R. H. New York Journal. Does our flag shield women? 13 February 1897.

- Duval, C. New York Journal. Evengelina Cisneros rescued by The Journal. 10 October 1897.

- Everett, Marshall History of the Philippines and the life and achievements of Admiral George Dewey: Also containing the life and exploits of Brig.-Gen. Fred Funston, and ... and the history of American expansion. J.S. Ziegler 1899 ASIN: B00087QNNS

- Funston, Frederick. Memoirs of Two Wars, Cuba and Philippine Experiences. New York: Charles Schribner's Sons, 1911

- Kendrick M. New York Journal. Better she died then reach Ceuta. 18 August 1897.

- Kendrick, M. New York Journal. The Cuban girl martyr. 17 February 1897.

- Kendrick, M. New York Journal. Spanish auction off Cuban girls. 12 February 1897.

- McCook, Henry C. The Martial Graves of Our Fallen Heroes in Santiago de Cuba. butt Philadelphia: Jacobs, 1899.

- Muller y Tejeiro, Jose. Combates y Capitulacion de Santiago de Cuba. Marques, Madrid:1898. 208 p. English traslation by US Navy Dept.

- Rubens, Horatio S. Liberty. The Story of Cuba. AMS Press New York, 1970 reprint of 1932 edition. SBN 404-00633-7

- Wheeler, Joseph. The Santiago Campaign, 1898.Lamson, Wolffe, Boston 1898.

- U.S. War Dept. Military Notes on Cuba. 2 vols. Washington, DC: GPO, 1898.

- Web

-

- "United Spanish War Veterans of New York State Records, ca. 1904 - ca. 1975". Official website of the New York State Library. December 2.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=and|year=/|date=mismatch (help); Unknown parameter|publishyear=ignored (help) - Dirks, Tim (November 9). "War and Anti-War Films". The Greatest Films.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=and|year=/|date=mismatch (help)

- "United Spanish War Veterans of New York State Records, ca. 1904 - ca. 1975". Official website of the New York State Library. December 2.

External links

- Centennial of the Spanish-American War 1898–1998 by Lincoln Cushing

- The World of 1898: The Spanish-American War - Library of Congress Hispanic Division

- William Glackens prints at the Library of Congress

- TeddyRoosevelt.com: information on Roosevelt and the Spanish American War

- Spanish-American War Centennial

- Images of Florida and the War for Cuban Independence, 1898 from the State Archives of Florida

- Individual state's contributions to the Spanish-American War: Illinois, United States of America Pennsylvania

- Sons of Spanish American War Veterans

- World Policy Journal America The Menace: France's Feud with Hollywood

- From 'Dagoes' to 'Nervy Spaniards,' American Soldiers' Views of their Opponents, 1898 by Albert Nofi