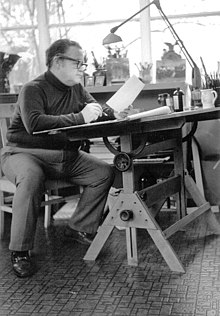

James F. Walker

James F. Walker | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | James F. Walker October 8, 1913 |

| Died | February 5, 1994 |

| Education | BA, MA, MFA, University of Iowa |

| Alma mater | University of Iowa |

| Known for | Mixed media surrealist images |

| Spouse | Leona Buchanan |

| Awards | Named to 100 Best New Talent List, 1956 and 1959 by Art in America |

James F. Walker (October 8, 1913 – February 5, 1994) was an American graphic artist,[1] twice named to the 100 Best New Talent List by Art in America.[2][3] Walker was particularly noted for his mixed media surrealist images, which he called "magic realism".[1] Walker was also an influential teacher.[4][5] His work has been exhibited in America, as well as in Germany and in France.[1]

Biography

[edit]Walker was born in Kirksville, Missouri, to James Franklin Walker Sr. and Mable Azalea Hunt. Walker's father was a landscape artist and an early influence,[1] and his brother was also an artist. Walker's passion for art evolved over his lifetime into a career as artist and teacher.[4] He studied at the University of Iowa in Iowa City, receiving a BFA degree. He then moved to New York City, where he studied at the American Artists School and at the studio of Nahum Tschacbasov.[1] His work was influenced by Tschacbasov's surrealist images.[6]

Walker joined the army in 1941, serving in the Aleutian Islands until 1945. During the war, he married Leona Buchanan. They had one child, Joy Walker Hall.[6] After World War II, he returned to the University of Iowa for an MA in art history and an MFA in studio printmaking.[1] At that time, he studied under Mauricio Lasansky,[7] considered "one of the fathers of twentieth-century American printmaking."[8] Lasansky had brought his printmaking skills and techniques from Stanley William Hayter's New York Atelier 17 to the University of Iowa School of Art and History (1945–1986). "If there is such a thing as a printmaking capital of the U.S., it could well be the Department of Graphic Arts at the State University of Iowa in Iowa City."[9]

After an interval teaching art in Kansas, Walker took a teaching position at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (1954–1959).[1] While at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Art in America twice named him to the 100 Best New Talent List, 1956 and 1959.[2][3]

Many years later, Santa Fe artist Lorraine Dickinson remembered her time in Walker's drawing and collage classes at the School of the Art Institute. Her work was "all in the representational mode," she said. "I didn't get into abstract until I studied with James F. Walker in Chicago. He was determined that we were all going to stop painting traditionally. It was like pulling teeth but I finally got it. A few times I tried to revert back to representational, but I get so bored with it."[10]

In 1960, Walker accepted a teaching position at Arlington High School and later at Elk Grove High School, both in Northwest Suburban High School District 214.[1][11] When interviewed by the Arlington High School newspaper, The Cardinal, Walker explained his philosophy of education: "The art department isn't run especially for the talented student, but rather to enrich the cultural background for all students."[12] He retired from teaching in 1975[1] and moved with his family to Gravette, Arkansas, where he continued to work as an artist until his death in 1994.[5]

Richard Calisch, division head of English and Fine Arts at Elk Grove High School said, "[Walker] was that special combination who had his own career and was also a fine teacher. The kids loved him."[5]

Work

[edit]

Walker's work builds on the legacy of his teacher, Mauricio Lasansky. Walker combines a spectrum of Lasansky's graphic techniques, including collage, monoprints, aquatint, pencil, brush, rubbings, etchings, and silkscreen. All combinations of these techniques appear in Walker's work.[4]

In a statement to the Chicago Society of Artists, Walker described his own work:

My paintings project my intense concern for, and interest in, the nature of texture surfaces within the context of meticulously rendered forms, revealing the essence of Magic Realism, a microscopic view of every infinitesimal area upon the canvas.[1]

As he said to a reporter from Algonquin Life, an Algonquin, Illinois, community newspaper,

A good artist paints what he sees, lives, thinks, and feels, although his finished product may not have the slightest congruency to what the ordinary person visualizes. In other words, he doesn't invent pictures—he portrays impressions—again, by what he sees, how he thinks, how he feels. The mistake that a young art student continues to make is this example: the country boy treks to the big city to attend art school. He decides that now he must paint with sophistication—rejecting all of his past association with country life, the hills, the trees, the farm animals, etc. This is a mistake.[6]

Walker's L.H. Double O.Q.

[edit]

Walker is perhaps best known for L.H. Double O.Q., often referred to as his Eisenhower Mona Lisa, although Wide World Photos referred to it as "Ike the Enigma." L.H. Double O.Q. won the Award for Collage, Casein, and Drawing in the 1964 Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago and Vicinity Show.[13] His painting is a reference to Marcel Duchamp's 1919 painting L.H.O.O.Q. In this work, Duchamp simply painted a mustache and beard onto a postcard reproduction of the Mona Lisa. Walker went further.[4]

Walker's painting—probably his most famous and controversial work—caused a media stir. It was a satirical portrait of President Dwight D. Eisenhower in drag with a Mona Lisa smile.

The big hit or most popular outrage, if you prefer—at this year's exhibit is a picture starkly titled, L.H. Double O.Q. It has the smiling face of President Eisenhower in a Mona Lisa pose, complete with headdress. A pair of false teeth floats in the sky. Somebody's antique hands—not Ike's—are in repose.[14]

A standalone photo in the Chicago Daily Defender called it "a 'kooky' portrait of Dwight D. Eisenhower in a Mona Lisa pose…"[15] According to a caption from UPI Telephotos, Walker "titled it L.H. Double O.Q. for what was 'no special reason at all.'"[16] Wide World Photos and UPI Telephotos broadcast photos of L.H. Double O.Q. to the world. Opinions on the piece fell roughly into two categories: "I like Ike," or "I don't like Ike."[14]

From the critics

[edit]"I found James Walker's collage, Creation of Eve, particularly good with its curious integration of old objects and new movement."[17]

Collections

[edit]Walker's works are included in the collections of the Art Institute of Chicago, Kansas Friends of Art, University of Iowa, and numerous private collections.[1] Three pieces by Walker are in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago: Pygmalion (1950), Birds in a Landscape (1952), and Landscape (1961).[11][18]

Exhibitions

[edit]- The Chicago Society of Artists Print, Drawing, and Watercolor Show, 1971, Old Town Triangle Center

- The Union League Club of Chicago, 1963

- Cabal: Works of Walker, Wirsum, Malloy, Wetzel, Ortiz, Nichols, Arsenault, Paschke, 1963 (Sedgwick Street Gallery, 401 West North Avenue, Chicago, Illinois)

- One Man Show, 1963 (Sedgwick Street Gallery, 401 West North Avenue, Chicago, Illinois)

- Fifty Paintings, Art Institute of Chicago

- International Exhibition of Contemporary Drawings

- Important Modern American Drawings Exhibition, The Contemporaries, Inc., New York City

- 59th Annual Exhibition of Western Art, Denver Art Museum, 1953

- First Biennial of Prints, Drawings and Water Colors, Art Institute of Chicago

- Le Dessin Contemporain Aux Etats-Unis, 1954 (Museum of Modern Art, Paris; Aix-en-Provence; Musée de Grenoble, France)

- Moderne Maler aus Chicago, Germany

- Contemporary drawings from 12 countries, 1945–1952 (Art Institute of Chicago [in collaboration with] the Toledo Museum of Art; Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford; San Francisco Museum of Art; Los Angeles County Museum; Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center; the J. B. Speed Art Museum, Louisville

- 16th Annual New Year Show, 1951 (Butler Art Institute of American Art, Youngstown, Ohio)[1]

Prizes

[edit]- 100 Best New Talent List, Art in America, 1956 and 1959

- Kansas Friends of Art (Purchase Award)

- Missouri Annual Art Salon

- 12th annual Missouri Artists Show

- Award for Collage, Casein, and Drawing, L.H. Double O.Q., 1964 (67th Annual Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago and Vicinity Show)

- William H. Tuthill Prize for Water Color, Landscape, 1961 (64th Annual Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago and Vicinity Show)

- Pauline Palmer Prize for Work in any Media, The Creation of Eve, 1957 (60th Annual Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago and Vicinity Show)

- Pauline Palmer Prize for Drawing, 1955 (58th Annual Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago and Vicinity Show)

- Contemporary drawings from 12 Countries 1952, The Art Institute of Chicago (Purchase Prize)[1]

Gallery

[edit]-

Untitled Collage

-

Untitled Oil Painting

-

Woman

-

Untitled Oil Painting

-

Untitled Collage

-

Three Old Birds

-

Silhouette of a Woman

-

Portrait of a Woman

-

Portrait of a Man

-

Portrait of a Boy

-

Mixed Media

-

Self Portrait

-

Recurring Enigma of Hagar

-

Memento Aquatique De La Jocande

-

Untitled Drawing

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Yochim, Louise Dunn (1979). Role and Impact: The Chicago Society of Artists. Chicago: Chicago Society of Artists.

- ^ a b Kuh, Katherine (February 1956). "New Talent in the U.S.A.". Art in America. 44 (1): 10.

- ^ a b "Nominations for New Talent 1959". Art in America Number One. 47 (1): 96. 1959.

- ^ a b c d Campbell, Genie (October 1, 1971). "For Jim Walker Football Led To Painting". The Herald. p. 1, Section 2.

- ^ a b c Schmitt, Anne (February 9, 1994). Daily Herald. p. 9.

- ^ a b c "Interesting Personalities Who Live in the Valley". Algonquin Life. April 22, 1959. p. 10.

- ^ "NMSU Presenting Art Exhibit of Three Generations". Kirksville Daily Express and News. September 9, 1984.

- ^ "History". School of Art and Art History, University of Iowa. Archived from the original on January 1, 2017. Retrieved May 12, 2014.

- ^ "Art: Iowa's Printmaker". Time. December 1, 1961. Retrieved May 12, 2014.

- ^ Weideman, Paul (March 26, 1999). "Opening the Door to the Ultimate Human Space". The Santa Fe New Mexican. p. Pasatiempo section, p 14.

- ^ a b Heise, Kenan (February 10, 1994). "James F. Walker, Artist, Teacher". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved July 15, 2014.

- ^ The Cardinal. October 21, 1960

- ^ Barry, Edward (April 30, 1964). "Winners in Chicago Artists Show Named". Chicago Tribune. p. b1, section 2.

- ^ a b Herguth, Robert J. (May 25, 1964). "They Like Ike, But Oh, That Modern Mona". The Chicago Daily News. p. 20.

- ^ Chicago Daily Defender (May 4, 1964). p. 12.

- ^ "We Still Like Ike". The Titusville Herald. May 5, 1964.

- ^ Weller, Allen S. (May 1957). "Chicago's No Jury Experiment". Arts. 31 (8): 17.

- ^ "Walker, James F." Art Institute of Chicago. Retrieved May 13, 2014.