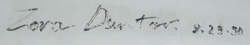

Zora Arkus-Duntov

Zora Arkus-Duntov | |

|---|---|

"Father of the Corvette" | |

| Born | Zachar Arkus December 25, 1909 |

| Died | April 21, 1996 (aged 86) Grosse Pointe, Michigan, U.S. |

| Resting place | National Corvette Museum |

| Alma mater | Technische Universität Berlin |

| Occupation | Engineer |

| Spouse | Elfriede "Elfi" Wolff |

Zachary "Zora" Arkus-Duntov (born Zachar Arkus; December 25, 1909 – April 21, 1996) was a Russian[1] and American engineer whose work on the Chevrolet Corvette earned him the nickname "Father of the Corvette."[2]: 6 He is sometimes erroneously referred to as the inventor of the Corvette; that title belongs to Harley Earl.[3] He was also a racing driver, appearing at the 24 Hours of Le Mans four times and taking class wins in 1954 and 1955.[2]

Early life

[edit]Arkus-Duntov was born Zachar Arkus in Brussels, Belgium, on December 25, 1909, into a Jewish Russian family. His father, Yakov “Jacques” Arkus, was a mining engineer on contract in Belgium, and his mother, Rachel Kogan, was a medical student.[2][4] After the family returned to their hometown of Saint Petersburg – then Petrograd – Duntov's parents divorced and his mother's new partner, Josef Duntov, an electrical engineer, moved into the household. Even after the divorce, Jacques continued to live with the family, and out of respect for both men, Zora and younger brother Yura took on the hyphenated last name of Arkus-Duntov.[2]

In 1927, the family moved to Berlin. While Duntov's early boyhood ambition was to become a streetcar driver, streetcars later gave way to motorcycles and automobiles. His first motorized vehicle was a 350 cc motorcycle, which he rode at nearby racetracks as well as through the streets of Berlin. When his parents, fearing for his safety, insisted he trade the cycle in for an automobile, Duntov bought a cycle-fendered model from a short-lived German manufacturer called Bob. The Bob was set up for oval track racing. It had no front brakes and weak rear brakes.[2] In 1934, Duntov graduated from Technische Hochschule Charlottenburg (known today as the Technische Universität Berlin). He also began writing engineering papers in German motor publications. While in Berlin Duntov met the fourteen year old Elfriede "Elfi" Wolff, who was in the city to study ballet and acrobatic dance.[5]: 109 The two kept in touch over several years while Elfi toured with dance troupes. She eventually settled in Paris as a dancer with the Folies Bergère.[2] The two married in February 1939, just before the outbreak of World War II.

Following the outbreak of the war first Yura, then Zora, joined the French Air Force. When France surrendered, Duntov obtained exit visas from the Spanish consulate in Marseilles, not only for Elfi and himself, but for his brother and parents as well. Elfi, who was still living in Paris at the time, made a dramatic dash to Bordeaux in her MG just ahead of the advancing Nazi troops. In the meantime, Duntov and Yura hid in a bordello. Five days later, Elfi met up with Duntov and his family and later they boarded a ship in Portugal bound for New York.[2]

Career

[edit]Ardun

[edit]Settling in Manhattan, in 1942 the two brothers established the Ardun Mechanical Corporation, the name a portmanteau of Arkus and Duntov. Ardun initially produced dies and punches for ammunition and later produced parts for aircraft.[5]: 111 In 1947 the company introduced their own aluminum, overhead valve, hemispherical combustion chamber cylinder heads for the flathead Ford V8 engine. Conceived by Duntov, the heads were designed by George Kudasch.[6] The purpose of the overhead valve design was to cure the persistent overheating of the valve-in-block flathead V8. The flathead 'siamesed' the two center exhaust ports into a single tube, creating a large heat transfer from the hot gases to the coolant that was eliminated in the overhead valve design. The Ardun heads allowed significant increases in power output from the Ford V8. Ardun grew into a 300 employee engineering company with a name as revered as Offenhauser, but the company later went out of business after some questionable financial decisions by a partner the Arkus-Duntov brothers had taken on.[2] Arkus-Duntov attempted to qualify a Talbot-Lago for the Indianapolis 500 in 1946 and 1947, but failed to make the race both years.[7] At this time Zora Arkus-Duntov got an invitation from a British company, while his brother decided to go into finances.

Allard

[edit]Soon he left the United States for England to do development work on the Allard sports car, co-driving it at the 24 Hours of Le Mans in 1952 and in 1953.[2] His goal was to improve and prepare the company's cars for the race "24 hours of Le Mans." It is noteworthy that some of them were Ford V8, on which Duntov applied, among other things, his old achievements. The owners and at the same time Allard racers Sydney Allard and his wife Eleanor noticed the achievements of the engineer. In 1952–53, Duntov acted as a Le Mans racer on the Allard J2X Le Mans and Allard JR models. In the same years, Carroll Shelby raced in Allard machines. Soon, Duntov was invited to join the Porsche team. He drove an 1100 cc Porsche 550 RS Spyder at Le Mans in 1954 and 1955, taking class wins both years.[2]

General Motors

[edit]

Arkus-Duntov joined General Motors in 1953 after seeing the Motorama Corvette on display in New York City. He found the car visually superb, but was disappointed with what was underneath. He wrote Chevrolet chief engineer Ed Cole that it would be a pleasure to work on such a beautiful car; he also included a technical paper which proposed an analytical method of determining a car's top speed. Chevrolet was so impressed, engineer Maurice Olley invited him to come to Detroit. On May 1, 1953, Arkus-Duntov started at Chevrolet as an assistant staff engineer.[2]

Shortly after going to work for Chevrolet, Arkus-Duntov set the tone for what he was about to accomplish in a memo to his bosses. The document, "Thoughts Pertaining to Youth, Hot Rodders and Chevrolet", laid out Duntov's views on overcoming Ford's lead in use by customizers and racers, and how to increase both the acceptance and the likelihood of success of the Chevrolet V8 in this market.[8] In 1957 Arkus-Duntov became Director of High Performance Vehicles at Chevrolet.[9] After helping to introduce the small-block V8 engine to the Corvette in 1955, providing the car with much-needed power, he set about showcasing the engine by ascending Pike's Peak in 1956 in a pre-production car (a 1956 Bel Air 4-door hardtop), setting a stock car record. He took a Corvette to Daytona Beach the same year and hit a record-setting 150 mph (240 km/h) over the flying mile.[citation needed] He also developed the famous Duntov high-lift camshaft and helped bring fuel injection to the Corvette in 1957.[2] He is credited with introducing the first mass-produced American car with four-wheel disc brakes.[10]

A conflict arose between Duntov and Chevrolet chief designer Bill Mitchell over the design of the new C2 Corvette "Sting Ray" model.[5]: 360, 361 Mitchell designed the car with a long hood and a raised windsplit that ran the length of the roof and continued down the back on a pillar that bisected the rear window into right and left halves. Duntov felt that the elongated hood interfered with the driver's view of the road ahead, and the rear pillar obscured the driver's view rearwards. The split rear window was widely criticized, and a one-piece backlite was put in its place the next year.[5]: 384, 385

Corvette SS

[edit]The first sports Corvette was designed and constructed by Duntov in 1956, who built 3 copies. The SR1 and SR2 projects met with Harley Earl's approval, which led to Duntov's proposal to establish the Corvette racing team being accepted with his promotion to the post of director of the high-performance car department in 1957. Duntov's new project was the Corvette SS with a magnesium body for the 24-hour Le Mans race. For preliminary testing of the car, the American counterpart, "12 hours of Sebring" was chosen. The difficulty was in the timing, since before the annual Sebring there were only 6 months left. According to rumors, in order to be in time, Duntov copied the frame for the new Corvette from the Mercedes 300SLR. To test the joint work of all the components, Duntov built a second car with a fiberglass body as a test mule. The results shown were positive, the team gained confidence in the victory. Later, the mule more than once proved its usefulness during the development and testing of new, improved versions. However, there was not enough time to fully test the racing Corvette. Therefore, having arrived in Sebring and joining the Corvette core team, SS pilot John Fitch still could not figure out the brake lock problem. The start of the race looked positive for the SS, but the problem with the brakes only intensified. By the end of the third lap, the pilot could no longer control the front axle of his car. After a quick tire change, Fitch continued to race, but already on the 23rd lap, the Corvette SS was forced to leave the track due to suspension and other mechanical problems. Despite the development setbacks of the SS, the new development of the Corvette attracted a lot of public attention, including setting a new lap record. But for Chevrolet, it became clear that with Le Mans would have to wait. Shortly after the race in Sebring, the situation for Duntov and his entire unit became more complicated.

A "Gentleman's agreement"

[edit]After the accident at the race at Le Mans in 1955, which claimed the lives of 83 people, the attitude toward motor racing changed dramatically. Numerous protests forced many companies to withdraw from the race, the organizers to review the safety rules, and Mercedes, who was accused of causing an accident and decided not to participate in car racing until the 70s. Dissatisfaction gradually increased in America, which is why the American Automobile Manufacturers Association (AMA) issued a recommendation to refuse to participate in races. However, several accidents over the next couple of years and, according to unconfirmed reports, the intervention of the US government led to the signing of the "Gentleman's Agreement" in 1957. By joining AMA, GM, Ford and Chrysler refused to participate in organized car racing and motorsport of any kind, which led to the cessation of all explicit support for racing in Chevrolet. At the same time, almost none of the automakers stopped the development of sports cars. Many found loopholes: from the establishment of third-party engineering companies (SEDCO Co.), which issued instructions for improving production cars with detailed indication of the part numbers of the automaker and step-by-step instructions for the support of “individual enthusiasts” of individual racers, as well as the production of “especially durable / long-life parts” Ideal for turning production cars into sports cars (Pontiac). Arkus-Duntov could not stop the new agreement. At his insistence, the driver Briggs Cunningham changed the three main Corvettes within 24 hours of Le Mans, each of which was equipped with an innovative 283-horsepower V8 fuel injected engine. Despite only achieving 10th place, it is important to note that the winners were the invincible Ferrari (6 places), Aston Martin (2 places) and Porsche (1 place), which did not have official development restrictions.

In 1962, GM Corporate, under serious pressure from the US government, decided to discontinue support for motorsport. It was exactly the same contract as the AMA, concluded in 1957, but now GM had made policies mandatory for its brands. The reason was that by 1961, about 53% of the entire US car market belonged to General Motors, which greatly interested the Department of Justice. In the event that the company's market were to grow to 60%, the antimonopoly department had promised to break up General Motors. Fearing this, management hoped to reduce auto racing revenues. But the most famous achievement of Arkus-Duntov was yet to come.

Corvette Grand Sport

[edit]In 1962 Ford officially withdrew from the AMA racing ban and soon after launched their "Total Performance" program, increasing factory participation in almost all major forms of motor racing. Right after Ford's declaration, Arkus-Duntov's Grand Sport program was approved. The intent was to create a special lightweight Corvette to race on international tracks against not only the Shelby Cobra and other GT cars, but also against racing prototypes from Ferrari, Ford and Porsche. The winning strategy was based on firstly making an aluminum version of the "small block" V8, equipped with special spark plugs (At 377 °C, its power was 550 hp. at 6400 rpm.) and secondly, an unprecedented decrease in vehicle weight.

A new ladder chassis with large diameter (4.5 in (114 mm)) tubular main rails was built. All body panels were of thin fiberglass with no gel coat, and the aluminum door handles were taken from an old Chevrolet pickup truck. Special attention was paid to aerodynamics. The door handles were lightened and recessed into the body, and the headlights were hidden behind transparent plastic. However, aerodynamic lift tended to cause the Grand Sport's front axle to come off the ground at high speeds. To help alleviate windage, ventilation holes were added throughout the body: "gills" on the hood, openings behind the front and rear wheels, and even multiple openings at the headlights were introduced. According to the terms of the FIA GT races of those years, the wheels had to be "within the body", so the wheel arches were expanded, but barely passed according to the standards, since they also served to remove air from under the belly of the car, which gave its special shape. In order to use the oncoming airflow even more efficiently, near the rear window there were two air intakes (one from each side) that cooled the brakes. Also behind the rear window was an air intake. Lightening was further facilitated by the use of organic aviation glass. The wheels also became lighter, thanks to the magnesium alloy material employed. The result of all the work was a reduction in weight from the 3,199 lb (1,451 kg) of the standard model to 1,900 lb (862 kg) for the Grand Sport.

News of the Grand Sport's development reached the board of General Motors, and Duntov was ordered to close the project and destroy all the cars. The board feared that the antimonopoly department would require the company to be broken up. Duntov agreed to stop work, but handed over three cars to Texas tycoon John Mecom and hid the remaining two in a Chevrolet research garage. Before sending the cars with chassis numbers #003 and #004 to Texas, he handed them over for testing to two private racers: Chicago Chevrolet dealer Dick Doane and Grady Davis from Gulf Oil. Homologation papers were filed with the Automobile Competition Committee for the United States (ACCUS), but the sanctioning body balked at homologating a car with only 5 of the required 100 copies having been built.[5] The car showed controversial results, but after some adjustments and improvements it won first place in the ACC championship in 1963. Driving chassis #004 was Dick Thompson, who earned the nickname "Flying Dentist," because of his original work. The victory in ACC became known to the GM bosses, who asked Duntov to return all the cars and not participate in races. Having received the cars back, Duntov improved the cars with chassis #003, #004 and #005, adding air vents and installing wider 9.5 inch wheels. Due to these changes, traction has increased, and lateral acceleration has decreased from 1.9G to the optimal 1.1G. After all the changes, Arkus-Duntov decided to send the Grand Sport to compete with Shelby Cobra at the Nassau Trophy race (1954-1966) in the Bahamas. Officially, all three of the improved Grand Sports were on behalf of tycoon John Mecom Jr. They beat all competitors by 10 seconds. Both the Shelby Cobra, and even the Ferrari GTO were left behind. However, this was not the end of the Grand Sport program. Taking the previously unimproved chassis #001 and #002, Duntov removed the roofs making them roadsters to improve aerodynamics, and was preparing to send them to the race in Daytona. But General Motors entered into an agreement with Duntov on the termination of any races, since the risks of the division of the company reached a maximum level. All 5 cars were handed out to private individuals and could no longer continue the competition due to the stop of design work. In 2009, the last surviving #002 chassis was auctioned off for $4.9M.

The end of Grand Sport project did not stop Duntov, and in 1964 he began work on the Chevrolet Engineering Research Vehicle II (CERV II) project. Duntov was made Chief Engineer for Corvette in 1967.[11]

Personal life

[edit]"(Bill) Mitchell hated him (Duntov), because he felt that Duntov was getting all of the praise for the Corvette, consequently, Mitchell never allowed Duntov into the Styling Center."[12] - Roy Vernon Lonberger

Retirement

[edit]Arkus-Duntov retired in 1975, and Dave McLellan became Chief Engineer of the Corvette. Following his retirement Arkus-Duntov remained active in the Corvette community. A member of the Drag Racing Hall of Fame, the Chevrolet Legends of Performance, and the Automotive Hall of Fame, he took part in the rollout of the one millionth Corvette at Bowling Green in 1992. He drove the bulldozer at the ground breaking ceremonies for the National Corvette Museum in 1994.[13] In a 2024 interview, Tadge Juechter recalled a mid-1990s onsite design review of the then upcoming 5th generation Corvette to which the retired Arkus-Duntov had been invited. After reviewing the extensive changes in the new design, Arkus-Duntov notably observed: "The engine is still in the front".[14] Six weeks before his death, Arkus-Duntov was guest speaker at "Corvette: A Celebration of an American Dream", an evening held at the showrooms of Jack Cauley Chevrolet Detroit.[2]

Death

[edit]Arkus-Duntov died in Detroit on April 21, 1996,[10] and his ashes were entombed at the National Corvette Museum in Bowling Green, Kentucky. Pulitzer Prize winning columnist George Will wrote in his obituary that "if... you do not mourn his passing, you are not a good American."[15]

Despite Duntov's work on the CERV I and CERV II and many mid-engine design studies, the idea of a mid-engine Corvette was not approved by GM management until 2019 with the announcement of the release of the eighth generation C8 Corvette. Rumors circulated that a high-performance version of the C8 could be named the "Zora".[16] On a pre-production camouflaged version, observers noted small stickers that resembled the profile of Zora Arkus-Duntov.[17]

Honors and awards

[edit]- Pikes Peak hill climb record, 1955[9]

- Daytona flying mile record, 1956[9]

- SEMA Hall of Fame, 1973[18]

- Automotive Hall of Fame, 1991[2][19]

- International Drag Racing Hall of Fame, 1994[20]

- National Corvette Museum Hall of Fame, 1998[21]

- Zora Arkus-Duntov Exhibition, Alexander Solzhenitsyn Center for Russian Émigrés, Moscow, May–June 2012,[22]

Racing record

[edit]Complete 24 Hours of Le Mans results

[edit]| Year | Team | Co-Drivers | Car | Class | Laps | Pos. | Class Pos. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1952 | Allard J2X Le Mans | S 8.0 |

- | DNF (Transmission) | |||

| 1953 | Allard J2R | S 8.0 |

65 | DNF (Engine) | |||

| 1954 | Porsche 550/4 RS Spyder | S 1.1 |

216 | 14th | 1st | ||

| 1955 | Porsche 550 RS Spyder | S 1.1 |

245 | 13th | 1st | ||

World Sportscar Championship results

[edit]| Saison | Team | Race car | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1953 | Allard | Allard J2R | USA | ITA | FRA | BEL | DEU | UK | MEX |

| DNF | |||||||||

| 1954 | Porsche | Porsche 550 | ARG | USA | ITA | FRA | UK | MEX | |

| 14 | |||||||||

| 1955 | Porsche | Porsche 550 | ARG | USA | ITA | FRA | UK | ITA | |

| 13 |

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "U.S., World War II Draft Cards Young Men, 1940-1947," digital images, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed May 21, 2024), Zachar Arkus-Duntov, serial no. 3334, order no. 507-A, Draft Board 30, New York County, New York; citing National Archives at St. Louis; St. Louis, Missouri; WWII Draft Registration Cards For New York City, 10/16/1940 - 03/31/1947; Record Group: Records of the Selective Service System, 147.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Burton, Jerry (2002). Zora Arkus-Duntov: The Legend Behind Corvette (Chevrolet). New York: Bentley Publishers. ISBN 0-8376-0858-9.

- ^ "Harley Earl, Father of the Corvette". corvetteactioncenter. The Torque Network, LLC. Retrieved 12 January 2016.

- ^ "Who Was Zora Arkus-Duntov?". revslibrary.omeka.net.

- ^ a b c d e Ludvigsen, Karl (2014). Corvette – America's Star Spangled Sports Car. Bentley Publishers. p. 416. ISBN 978-0-8376-1659-9.

- ^ Tefft, Gary (7 April 2008). "Designer of Ardun Heads Dies". www.hotrod.com.

- ^ Zora Arkus-Duntov, Champ Car Stats, Retrieved 2010-12-24

- ^ Zora Arkus-Duntov (16 December 1953). Thoughts Pertaining to Youth, Hot Rodders and Chevrolet (PDF) (Report). Chevrolet.

- ^ a b c "Arkus-Duntov, Zora". GM Heritage Center. Archived from the original on 4 January 2013. Retrieved 6 November 2019.

- ^ a b Keith Bradsher (April 24, 1996), "Zora Arkus-Duntov, 86, Who Made Corvette a Classic, Dies", The New York Times, retrieved 2012-02-21

- ^ Sherman, Don (31 October 2014). "The Story of Zora Arkus-Duntov, the Bad-Ass Who Made the Corvette an Icon". www.caranddriver.com.

- ^ Bowman, Bill. "Astro I Concept". Generations of GM. General Motors. Archived from the original on 28 Sep 2014. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- ^ Daniel Strohl (March 2007), "Zora Arkus-Duntov", Hemmings Muscle Machines, retrieved 2012-02-21

- ^ "RICK CONTI TALKS WITH CORVETTE CHIEF ENGINEER TADGE at NCM BASH 2024". YouTube. 19 May 2024. Retrieved 20 May 2024.

- ^ Will, George (April 29, 1996), A Tribute to 1950s and Man Who Revved Up Corvettes, Washington Post Writers Group, retrieved 2012-02-21

- ^ Silvestro, Brian; Perkins, Chris (29 July 2019). "Mid-Engine Corvette: Everything We Know". www.roadandtrack.com.

- ^ Cornett, Keith (12 April 2019). "[PICS] Corvette Team Gives Nod to Zora Arkus-Duntov with Easter Egg Profile Graphics". www.corvetteblogger.com.

- ^ Zora Arkus-Duntov 1973 Inductee, SEMA

- ^ "Zora Arkus-Duntov Inducted 1991". Automotive Hall of Fame.

- ^ "The International Drag Racing Hall of Fame – All Time Members List". garlits.com. Don Garlits Museum of Drag Racing.

- ^ Zora Duntov inductee page, National Corvette Museum, retrieved 2012-02-21

- ^ Burton, Jerry (22 June 2012). "Champion of the Corvette, Feted in the Land He Left". The New York Times. Retrieved 22 December 2012.

- 1909 births

- 1996 deaths

- 24 Hours of Le Mans drivers

- General Motors executives

- Belgian emigrants to the United States

- Belgian Jews

- Technische Universität Berlin alumni

- American people of Belgian-Jewish descent

- American people of Russian-Jewish descent

- Belgian people of Russian descent

- Jewish American scientists

- American automotive pioneers

- World Sportscar Championship drivers

- Chevrolet Corvette

- 20th-century American engineers

- General Motors people

- Belgian racing drivers

- French Air Force personnel of World War II

- 20th-century American Jews

- Porsche Motorsports drivers

- Racing drivers from Brussels

- Racing drivers from New York City

- Racing drivers from New York (state)