Mersin

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Mersin | |

|---|---|

Clockwise from top: Mersin Skyline, Yapraklı Koy, St. Anthony Latin Catholic Church of Mersin, Yenişehir, Soli Pompeiopolis, Kızkalesi | |

| Coordinates: 36°48′N 34°38′E / 36.800°N 34.633°E | |

| Country | Turkey |

| Region | Mediterranean |

| Province | Mersin |

| Districts | Akdeniz, Mezitli, Toroslar, Yenişehir |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Vahap Seçer (CHP) |

| Area | |

| • Urban | 1,708.6 km2 (659.7 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 10 m (30 ft) |

| Population (2022)[1] | |

| • Urban | 1,040,507 |

| • Urban density | 610/km2 (1,600/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (TRT) |

| Postal code | 33XXX |

| Area code | (+90) 324 Metropolitan Municipality |

| Licence plate | 33 |

| Website | Mersin |

Mersin (pronounced [ˈmæɾsin]) is a large city and port on the Mediterranean coast of southern Turkey. It is the provincial capital of the Mersin Province (formerly İçel). It is made up of four district governorates, each having its own municipality: Akdeniz, Mezitli, Toroslar and Yenişehir.

Mersin lies on the western side of Çukurova, a geographical, economic and cultural region of Turkey. It is an important hub for Turkey's economy, with Turkey's largest seaport located here. The city hosted the 2013 Mediterranean Games.

As urbanisation continues eastward, a larger metropolitan region combining Mersin with Tarsus and Adana (the Adana-Mersin Metropolitan Area) is in the making with more than 3.3 million inhabitants.

Çukurova International Airport (COV), 74 kilometres (46mi) from Mersin city center, is the nearest international airport. There are ferry services from Mersin to Famagusta (Mağusa) in Northern Cyprus.[2] Mersin is linked to Adana via Tarsus by way of TCDD trains.

Etymology

[edit]The city was named after the aromatic plant genus Myrsine (Turkish: Mersin, Greek: Μυρσίνη) in the family Primulaceae, a myrtle that grows in abundance in the area. The 17th-century Ottoman traveler Evliya Çelebi also recorded in his Seyahatnâme that there was a clan named the Mersinoğulları (Sons of Mersin) living in the area.[3] In the 19th century Mersin was also referred to as Mersina.

History

[edit]Prehistory

[edit]This coast has been inhabited since the 9th millennium BC. Excavations by John Garstang of the hill of Yumuktepe[4] have revealed 23 levels of occupation, the earliest dating from ca. 6300 BC. Fortifications were put up around 4500 BC, but the site appears to have been abandoned between 350 BC and 300 BC.

Classical era

[edit]Over the centuries, the city was ruled by many states and civilisations including the Hittites, Assyrians, Urartians, Persians, Greeks, Armenians, Seleucids and Lagids. During the Ancient Greek period, the city bore the name Zephyrion (Greek: Ζεφύριον[5]) and was mentioned by numerous ancient authors. Apart from its natural harbour and strategic position along the trade routes of southern Anatolia, the city profited from trade in molybdenum (white lead) from the neighbouring mines of Coreyra. Ancient sources attributed the best molybdenum to the city, which also minted its own coins.[citation needed]

The area later became a part of the Roman province of Cilicia, which had its capital at Tarsus, while nearby Mersin was the major port.[citation needed] The city, whose name was Latinised to Zephyrium, was renamed as Hadrianopolis in honour of the Roman emperor Hadrian.[citation needed] After the death of the emperor Theodosius I in 395 and the subsequent permanent division of the Roman Empire, Mersin fell into what became the Byzantine Empire.[citation needed]

The city was an episcopal see under the Patriarchate of Antioch. Le Quien names four bishops of Zephyrium:[6] Aerius, present at the First Council of Constantinople in 381; Zenobius, a Nestorian, the writer of a letter protesting the removal of Bishop Meletius of Mopsuestia by Patriarch John of Antioch (429–441); Hypatius, present at the Council of Chalcedon in 451; and Peter, present at the Council in Trullo in 692. The bishopric is included in the Catholic Church's list of titular sees, but since the Second Vatican Council no new titular bishop of this Eastern see has been appointed.[7]

Medieval period

[edit]Cilicia was conquered by the Arabs in the early 7th century, by which time it appears Mersin was a deserted site. The Arabs were followed by the Egyptian Tulunids, then by the Byzantines between 965 and c.1080 and then by the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia. Under Armenian Cilicia, the region of Mersin served as the powerbase for the House of Lampron. From 1362 to 1513 the region was captured and governed by the Ramadanid Emirate, first as a protectorate of the Mamluk Sultanate, then as an independent state for roughly a century and then as a protectorate of the Ottoman Empire from 1513 until 1518 when it was annexed into the Ottoman Empire and turned into an imperial province.[citation needed]

Ottoman Empire

[edit]

This section needs expansion with: the city's history between 16th and 19th century. You can help by adding to it. (November 2020) |

During the American Civil War, the region became a major supplier of cotton to make up for the high demand due to shortage. Railroads were extended to Mersin in 1866 from where cotton was exported by sea, and the city developed into a major trade centre.[8]

In 1909, Mersin's port hosted 645 steamships and 797,433 tons of goods. Before World War I, Mersin exported mainly sesame seeds, cotton, cottonseed, cakes and cereals, and livestock. Cotton was exported to Europe, grain to Turkey and livestock to Egypt. Coal was the main import into Mersin at this time. Messageries Maritimes was the largest shipping line to use the port at Mersin.[9]

In 1918, the Ottoman Empire collapsed and Mersin was occupied by French and British troops in accordance with the Treaty of Sèvres. It was recovered by the Turkish Army in 1921 at the end of the Franco-Turkish War. In 1924, Mersin was made a province, and in 1933 Mersin and İçel provinces were merged to form the (greater Mersin) İçel Province. The capital of the province was Mersin. In 2002 the name of the province was changed to Mersin Province.[10]

As of 1920, Mersin had five piers at its port, with one privately owned by a railroad company serving Mersin, Tarsus, and Adana.[11]

Modern Mersin

[edit]

Today, Mersin is a large city spreading out along the coast. It has the longest seashore in Turkey as well as in the Eastern Mediterranean.[citation needed]

The Metropolitan Municipality has rescued long stretches of the seafront with walkways, parks and statues, and there are still palm trees on the roadsides.

Since the start of the Syrian War in 2011 Mersin has acquired a large population of Syrian refugees.

On 6 February 2023 Mersin was shaken by the twin Turkish-Syrian earthquakes. Citizens made homeless in cities further to the east also flocked to Mersin in search of shelter.

Local Attractions

[edit]There are six museums within the Mersin urban area; Mersin Archaeological Museum,[12] Mersin Atatürk Museum, Mersin Naval Museum, Mersin State Art and Sculpture Museum, Mersin Urban History Museum, Mersin Water Museum.

In the western suburb of Viranşehir (Ruined City) the remains of the ancient city of Soli/Pompeiiopolis stand close to the sea. Only two colonnades dating from the 2nd or 3rd century are obvious although the outline of the agora and of a mole from the harbour can just about be made out.[13]

The Chasms of Heaven and Hell are located in the rural region of Silifke, a district in Mersin.[14] The chasms are two sinkholes that were naturally formed from underground waters melting the layer of limestone above.[14] The heaven sinkhole has a small monastery located in the corner of the entrance.[14] The deepest point of the sinkhole is 135 meters deep.[14] The hell sinkhole is 128 meters deep.[14] In mythology, there is a story of Zeus temporarily trapping Typhon in the sinkhole.[14]

The city has a total of three modern shopping malls, from which the Forum Mersin is the largest one. Mersin Marina can also be considered a shopping center with over 40 shops, apart from its main function as a marina. In the old city center you will find further shopping opportunities and bazaar-like shopping areas.

Geography

[edit]Unlike the mountainous rugged terrain of the whole province Mersin is located at the western edge of the Çukurova plain. Earthquake risk of the city is relatively low especially compared to other regions of Turkey, but due to its closeness to several other fault lines in Anatolia, the city center, which was built on an alluvial deposit is considered to be a risk region.[16][17]

Climate

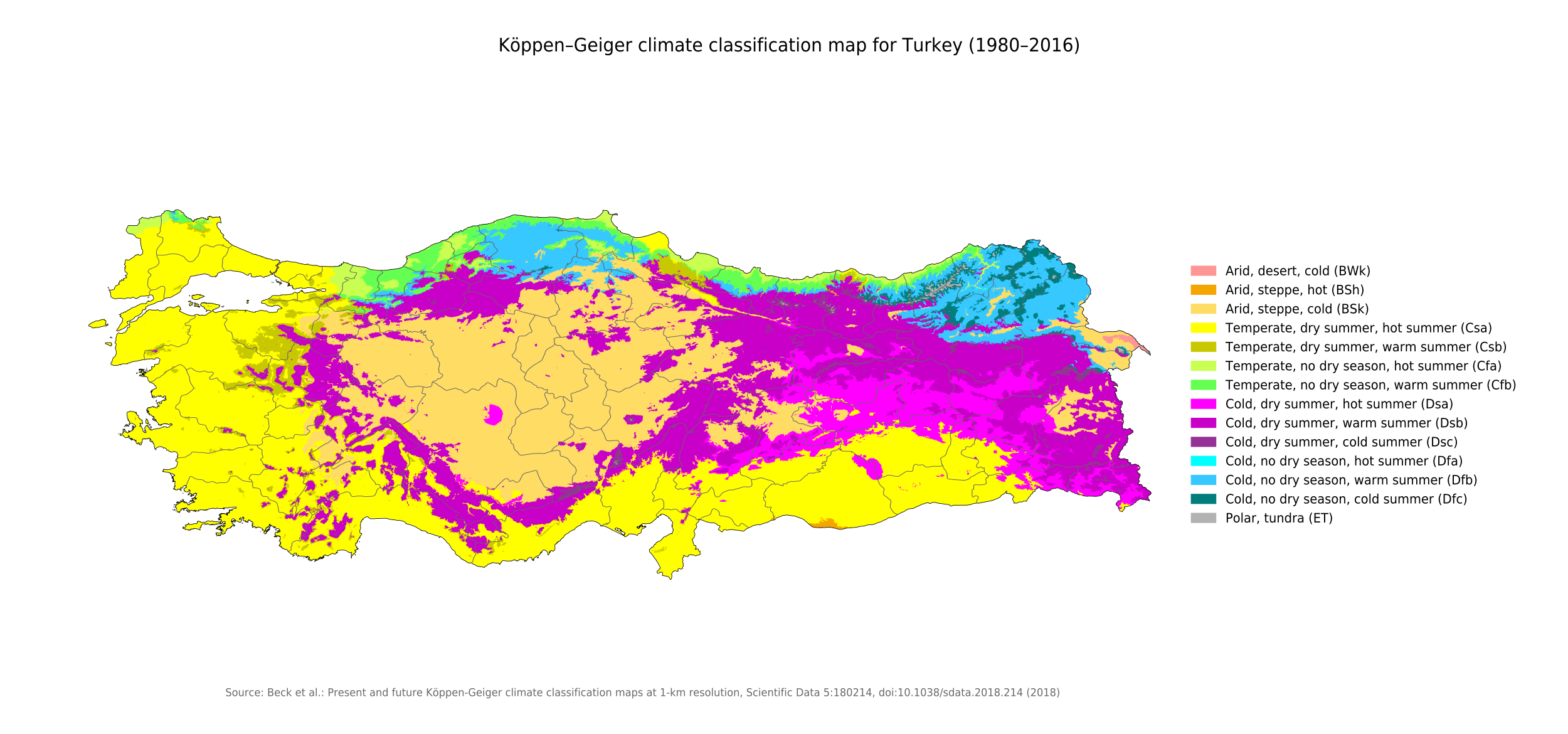

[edit]Mersin has a hot-summer Mediterranean climate (Köppen climate classification: Csa, Trewartha climate classification: Cs), a type of subtropical climate with hot, humid summers and mild, wet winters. Mersin has its highest rainfall in winter. The driest months are in summer with hardly any rainfall at all. The highest temperature of Mersin was recorded on 3 September 2020 at 41.5 °C (106.7 °F), and the lowest was recorded on 6 February 1950 at −6.6 °C (20.1 °F).

| Climate data for Mersin (1991–2020, extremes 1940–2023) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 25.2 (77.4) |

26.5 (79.7) |

29.8 (85.6) |

34.7 (94.5) |

36.0 (96.8) |

40.0 (104.0) |

38.1 (100.6) |

39.8 (103.6) |

41.5 (106.7) |

37.5 (99.5) |

31.0 (87.8) |

27.0 (80.6) |

41.5 (106.7) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 15.2 (59.4) |

16.2 (61.2) |

19.0 (66.2) |

22.2 (72.0) |

25.8 (78.4) |

29.1 (84.4) |

31.9 (89.4) |

32.8 (91.0) |

31.1 (88.0) |

27.9 (82.2) |

22.1 (71.8) |

16.9 (62.4) |

24.2 (75.6) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 11.0 (51.8) |

12.0 (53.6) |

14.9 (58.8) |

18.2 (64.8) |

22.1 (71.8) |

25.8 (78.4) |

28.7 (83.7) |

29.3 (84.7) |

27.0 (80.6) |

23.0 (73.4) |

17.2 (63.0) |

12.6 (54.7) |

20.1 (68.2) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 7.6 (45.7) |

8.2 (46.8) |

10.9 (51.6) |

14.4 (57.9) |

18.6 (65.5) |

22.6 (72.7) |

25.8 (78.4) |

26.3 (79.3) |

23.2 (73.8) |

18.6 (65.5) |

13.0 (55.4) |

9.1 (48.4) |

16.5 (61.7) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −6.3 (20.7) |

−6.6 (20.1) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

0.6 (33.1) |

7.0 (44.6) |

12.0 (53.6) |

16.1 (61.0) |

15.0 (59.0) |

11.0 (51.8) |

2.7 (36.9) |

−3.3 (26.1) |

−3.0 (26.6) |

−6.6 (20.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 115.9 (4.56) |

79.0 (3.11) |

56.1 (2.21) |

34.6 (1.36) |

26.7 (1.05) |

12.0 (0.47) |

9.3 (0.37) |

7.3 (0.29) |

13.4 (0.53) |

35.7 (1.41) |

80.2 (3.16) |

162.7 (6.41) |

632.9 (24.92) |

| Average rainy days | 10.07 | 9.07 | 7.37 | 7.27 | 6.07 | 2.70 | 1.00 | 1.03 | 2.13 | 5.27 | 6.37 | 10.83 | 69.2 |

| Average snowy days | 0 | 0.19 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.06 | 0.25 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 62.5 | 62.5 | 63.6 | 66.7 | 69.3 | 71.2 | 72.1 | 69.7 | 63.2 | 57.6 | 56.7 | 61.9 | 64.8 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 148.8 | 158.2 | 210.8 | 231.0 | 263.5 | 294.0 | 313.1 | 303.8 | 273.0 | 235.6 | 177.0 | 142.6 | 2,751.4 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 4.8 | 5.6 | 6.8 | 7.7 | 8.5 | 9.8 | 10.1 | 9.8 | 9.1 | 7.6 | 5.9 | 4.6 | 7.5 |

| Source 1: Turkish State Meteorological Service[18] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: NOAA (humidity, 1991-2020),[19] Meteomanz(snow days 2008-2023)[20] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]The population of the city was 1,040,507 according to 2022 estimates.[1] This figure refers to the urban part of the four districts Akdeniz, Mezitli, Toroslar and Yenişehir, that had a total population of 1,077,054 at the end of 2022.[21] As of a 2021 estimation, the population of the Adana-Mersin Metropolitan Area was 3,300,000 inhabitants, making it the 4th most populous area of Turkey.[citation needed]

Religion

[edit]The Mersin Interfaith Cemetery, in the Yusuf Kılıç district, serves as a cemetery for all religions with graves of Muslims, Christians and Jews.[22][23]

-

Muğdat Mosque in Yenişehir was built in the 1980s

-

Mersin Cemevi, an Alevi place of worship

Economy and transportation

[edit]

The Port of Mersin is the mainstay of city's economy. It is an international hub for many vessels routing to European countries, with a capacity of 6,000 ships per year.

Next to the port is the Mersin Free Zone, established in 1986 as the first free zone in Turkey, the zone is a publicly owned centre for foreign investors, close to major markets in the Middle East, North Africa, Europe, Russia and Central Asia. In 2002 the free zone's trading volume was US$51.8 billion.[24]

Historically, Mersin was a major producer of cottonseed oil.[25] The area around Mersin is famous for citrus and cotton production. Bananas, olives and assorted other fruits are also produced.

Mersin has highway connections to the north, east and west. It is also connected to the southern railroad. Mersin railway station in the district of Akdeniz has been in use since 1886. Opened on 28 February 2015, Mersin Bus Terminus is the terminus for intercity bus services, replacing the bus station that had been in the city centre since 1986. A metro system with 11 stations and a length of 13.4 kilometres (8.3 mi) is scheduled to open at the end of 2026.[26]

Since August 2024, the city is served by Çukurova International Airport.

Work is underway[when?] to complete the Akkuyu Nuclear Power Plant, Turkey's first nuclear power plant, some 80 miles west of Mersin.[27] Environmental groups, such as Greenpeace, have opposed the construction.[28]

Culture

[edit]

Mersin is home to a State Opera and Ballet, the fourth in Turkey after Istanbul, İzmir and Ankara. Mersin International Music Festival was established in 2001 and takes place every October.

The photography associations Mersin Fotoğraf Derneği (MFD) and Mersin Olba Fotoğraf Derneği (MOF) are amongst the city's most popular and active cultural organisations. Some cultural activities are sponsored by the İçel Sanat Kulübü (Art Club of Mersin) and Mediterranean Opera and Ballet Club.

The Mersin Citrus Festival is a festival organized to promote the citrus produced in Mersin.[29] The festival typically includes folk dancers from different traditions and sculptures constructed from different types of citrus.[30] The first festival was held in 2010. The festival is held annually on a weekend in November.[30]

Cuisine

[edit]Mersin is best known in Turkey for its tantuni, and restaurants serving it can be found all over the country. The provincial cuisine includes specialties such as:

- Ciğer kebap, (liver on mangal), typically served on lavaş with an assortment of meze at 12 skewers at a time,

- Tantuni, a hot lavaş wrap consisting of julienned lamb stir-fried on a sac on a hint of cottonseed oil,

- Bumbar or mumbar, lamb intestines filled with a mixture of rice, meat and pistachios, that are served either grilled or steamed, famous throughout the Levant ,

- Cezerye, a lokum-like delight made of caramelized carrot paste, covered in (sometimes sliced) pistachios and often also sprinkled with ground coconut,

- Karsambaç, a variety of shaved ice served with pekmez or honey as toppings,

- Künefe, a wood-oven baked dessert based on a mixture of cheese and pastry; known all throughout the Levant,

- Kerebiç, a shortbread filled with pistachio paste, also famous throughout the Levant,

- Şalgam suyu, a beverage made of fermented red carrots, very popular in Southern Turkey.

Media

[edit]- Local TV channels

- Kanal 33

- İçel TV

- Sun RTV

- Güney TV

- Local radio channels

- Radyo Metropol (101.8)

- Tarsus Süper FM (91.1)

- Tempo 94 FM (94.3)

- Örgün FM (94.7)

- Tarsus Star FM (95.5)

- Tarsus Radyo Time (97.7)

- Flaş FM (98.3)

- Mix FM (91.6) (sadece yabancı müzik, 1993-günümüz)

- Kent Radyo (98.5)

Sports

[edit]The city was formerly home to Mersin İdman Yurdu, a football club that played in the Süper Lig as recently as the 2015–16 season. The men's basketball team of the Mersin Büyükşehir Belediyesi S.K. plays in the Turkish Basketball League while its women's basketball team plays in the Turkish Women's Basketball League.

The city has one football stadium, Mersin Arena, with a seating capacity of 25,534. There was another stadium, Tevfik Sırrı Gür Stadium, which had a capacity of 10,128 and is now demolished and turned into a park. The men's and women's basketball teams of the Mersin Büyükşehir Belediyesi S.K. play their home matches at the Edip Buran Sport Hall, which has a seating capacity of 2,700.

Eleven new sports venues were built for Mersin to host the 2013 Mediterranean Games. The Servet Tazegül Arena, the fourth biggest indoor arena of Turkey with its 7,500 seating capacity, hosted the men's basketball events and the volleyball finals of the Games.[31] The athletics and paralympic athletics events were held at the Nevin Yanıt Athletics Complex.[32]

-

Sporthall in Mersin

Universities

[edit]

Mersin University was founded in 1992 and started teaching in 1993–1994, with eleven faculties, six schools and nine vocational schools. The university has had about 10,000 graduates, has broadened its current academic staff to more than 2,100 academicians.

Toros University is a non-profit private foundation established in Mersin in 2009.

Twin towns – sister cities

[edit] Durban, South Africa

Durban, South Africa Gazi Mağusa, Northern Cyprus [note 1]

Gazi Mağusa, Northern Cyprus [note 1] Kherson, Ukraine

Kherson, Ukraine Klaipėda, Lithuania

Klaipėda, Lithuania Kushimoto, Japan, where there is a Turkish Memorial and Museum in commemoration of the 1890-sunken Ottoman frigate Ertuğrul. A street in Mersin is named after the Japanese town.

Kushimoto, Japan, where there is a Turkish Memorial and Museum in commemoration of the 1890-sunken Ottoman frigate Ertuğrul. A street in Mersin is named after the Japanese town. Nizhnekamsk, Russia

Nizhnekamsk, Russia Oberhausen, Germany

Oberhausen, Germany Ölgii, Mongolia

Ölgii, Mongolia Ufa, Russia

Ufa, Russia Valparaíso, Chile

Valparaíso, Chile West Palm Beach, United States

West Palm Beach, United States

- ^ Gazi Mağusa, also known as Famagusta is de jure a part of Republic of Cyprus, but the city is de facto administrated by the self declared Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus since the Turkish invasion of Cyprus. The twinning is between Northern Cypriot and Turkish administration.

Notable people

[edit]- Nevin Yanıt – athlete

- Mustafa Üstündağ – actor

- Erman Toroğlu – footballer

- Haldun Dormen – theatre & film actor and director

- Musa Eroğlu – Turkish folk music artist, folk poetry, composer, musician

- Bergen – Turkish Arabesque singer

- Mehmet Emin Karamehmet - businessman and founder of Çukurova Holding

- Ahmet Mete Işıkara – scientist

- Müfide İlhan – first woman mayor in Turkey in the 1950s

- Gencay Kasapçı – painter

- Özgecan Aslan - Mersin University Psychology student

- Konca Kuriş - Islamic feminist writer, journalist and activist

- Metin Özülkü - musician, singer-songwriter, composer and arranger

- Ahmet Kireççi (aka Mersinli Ahmet) – Olympic medalist wrestler

- Nevit Kodallı – composer

- Seyhan Kurt – poet, writer, sociologist

- Cemal Mersinli – a pasha of the Ottoman Empire

- Olga Nakkas – film director

- İpek Ongun – writer

- Macit Özcan – former mayor

- Suna Tanaltay – writer and psychologist.

- Eda Özülkü - Turkish pop musician

- Atıf Yılmaz – film director and producer

- Mabel Matiz – Turkish pop musician

- Tuğba Şenoğlu – volleyball player

- Emre Demir – footballer

- Manuş Baba - Pop folk musician

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "Mersin". citypopulation.de. Retrieved 26 January 2024.

- ^ SysAdmin. "Akgünler Denizcilik | Kıbrıs Gemi Biletleri | Online Bilet Al". Akgünler Denizcilik | Kıbrıs Feribot-Kıbrıs Gemi Bileti (in Turkish). Retrieved 2022-11-26.

- ^ İçel: Mersin- Tarsus- Çamlıyayla- Erdemli- Silifke- Aydıncık- Bozyazı- Anamur- Gülnar- Mut (Kültür, Turizm ve Tanıtım yayınları, 1992), p. 7.

- ^ "YUMUKTEPE HÖYÜĞÜ Toroslar Belediyesi". Toroslar Belediyesi. Retrieved 2022-11-26.

- ^ http://www.jannis.tu-berlin.de/City_&_Ruler_Names.html Archived 2007-06-14 at archive.today retrieved June 14, 2007

- ^ Le Quien, Michel (1740). "Ecclesia Zephyrii". Oriens Christianus, in quatuor Patriarchatus digestus: quo exhibentur ecclesiæ, patriarchæ, cæterique præsules totius Orientis. Tomus secundus, in quo Illyricum Orientale ad Patriarchatum Constantinopolitanum pertinens, Patriarchatus Alexandrinus & Antiochenus, magnæque Chaldæorum & Jacobitarum Diœceses exponuntur (in Latin). Paris: Ex Typographia Regia. cols. 883–884. OCLC 955922747.

- ^ Annuario Pontificio 2013 (Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 2013, ISBN 978-88-209-9070-1), p. 1012

- ^ "Mersin (İçel)". www.cometoturkey.com. Retrieved 2024-01-22.

- ^ Prothero, G.W. (1920). Anatolia. London: H.M. Stationery Office.

- ^ "Tarih".

- ^ Prothero, G.W. (1920). Anatolia. London: H.M. Stationery Office.

- ^ "Mersin Museum | Turkish Museums". Turkish Museum. Retrieved 2022-11-26.

- ^ Freely, John (1998). The Eastern Mediterranean Coast of Turkey (1st ed.). Istanbul: SEV Matbaacılık ve Yayıncılık. pp. 215–20. ISBN 978-975-8176-22-9.

- ^ a b c d e f "SİLİFKE CHASM OF HEAVEN AND HELL". T.C. Kültür ve Turizm Bakanlığı (in Turkish). Retrieved 2022-12-12.

- ^ "Present and future Köppen-Geiger climate classification maps at 1-km resolution". Nature Scientific Data. DOI:10.1038/sdata.2018.214.

- ^ "Mersin deprem bölgesi mi? Mersin'de deprem risk var mı? Mersin'de fay hattı var mı?". Haberler (in Turkish). 2023-02-23. Retrieved 2023-03-01.

- ^ "TÜRKİYE DEPREM RİSK HARİTASI GÜNCEL | Türkiye'de aktif kaç fay hattı var, hangi illerden fay hattı geçiyor? Marmara, İç Anadolu, Karadeniz, Ege en az ve en..." www.hurriyet.com.tr (in Turkish). Retrieved 2023-03-01.

- ^ "Resmi İstatistikler: İllerimize Ait Mevism Normalleri (1991–2020)" (in Turkish). Turkish State Meteorological Service. Retrieved 6 July 2021.

- ^ "World Meteorological Organization Climate Normals for 1991–2020: Mersin". National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 2 August 2023.

- ^ "Mersin - Weather data by months". Meteomanz. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ "Address-based population registration system (ADNKS) results dated 31 December 2022, Favorite Reports" (XLS). TÜİK. Retrieved 19 September 2023.

- ^ "Mersin Mezarlığı'nda Hristiyan ve Müslümanlar birlikte dua etti-Mersin Haberleri". Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2014-07-25.

- ^ GÜNGÖR, İZGİ (10 March 2008). "Not only bodies, but prejudices buried in Mersin Cemetery". Hurriyet Daily News. Retrieved 13 January 2014.

- ^ "Mersin Free Zone". www.mtso.org.tr. Retrieved 2022-11-26.

- ^ Prothero, G.W. (1920). Anatolia. London: H.M. Stationery Office. p. 113.

- ^ "Ulaştırma ve Altyapı Bakanlığının İstanbul'daki 7 metro hattı 2023'te tamamlanmış olacak". www.aa.com.tr. Retrieved 2022-11-26.

- ^ "Akkuyu NPP Construction Project AKKUYU NÜKLEER A.Ş." www.akkunpp.com. Retrieved 2022-11-26.

- ^ Demonstration against nuclear power in Mersin Archived 2011-08-15 at the Wayback Machine Firat News agency

- ^ "8. Mersin Narenciye Festivali 12-13 Kasım'da". 8. Mersin Narenciye Festivali 12-13 Kasım'da (in Turkish). 2022-10-27. Retrieved 2022-12-12.

- ^ a b "FESTİVALİN AMACI". 8. Mersin Narenciye Festivali 12-13 Kasım'da (in Turkish). 2019-05-16. Retrieved 2022-12-12.

- ^ "Mersin, Tesisleri ile Fark Yaratacak..." (in Turkish). Mersin 2013 XVII Akdeniz Oyunları. Archived from the original on 2013-05-07. Retrieved 2013-05-14.

- ^ "Nevin Yanıt Atletizm Kompleksi" (in Turkish). 2013 Mersin XVII Akdeniz Oyunlatı. Archived from the original on 2013-05-12. Retrieved 2013-05-15.

- ^ "Kardeş Şehirlerimiz". mersin.bel.tr (in Turkish). Mersin. Archived from the original on 2020-02-29. Retrieved 2020-01-19.

- Blue Guide, Turkey, The Aegean and Mediterranean Coasts (ISBN 978-0-393-30489-3), pp. 556–557.

- Blood-Dark Track: A Family History (Granta Books) by Joseph O'Neill, contains a detailed and evocative history of the city, viewed from the perspective of a Christian Syrian family long resident in Mersin.

- Richard Talbert, Barrington Atlas of the Greek and Roman World, (ISBN 978-0-691-03169-9), p. 66

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Zephyrium". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Zephyrium". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

External links

[edit]- Articles with short description

- Mersin

- Çukurova

- Cilicia

- Mediterranean port cities and towns in Turkey

- Ancient Greek archaeological sites in Turkey

- Cities in Turkey

- Populated coastal places in Turkey

- Catholic titular sees in Asia

- Seaside resorts in Turkey

- Populated places in Mersin Province

- Geography of ancient Anatolia