Moorish idol

| Moorish idol | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Acanthuriformes |

| Suborder: | Acanthuroidei |

| Family: | Zanclidae |

| Genus: | Zanclus Cuvier in Cuvier and Valenciennes, 1831 |

| Species: | Z. cornutus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Zanclus cornutus | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

| |

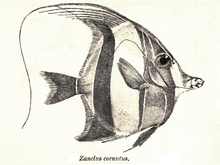

The Moorish idol (Zanclus cornutus) is a species of marine ray-finned fish belonging to the family Zanclidae. It is the only member of the monospecific genus Zanclus and the only extant species within the Zanclidae. This species is found on reefs in the Indo-Pacific region.

Taxonomy

[edit]The Moorish idol was first formally described as Chaetodon cornutus in 1758 by Carl Linnaeus in the 10th edition of the Systema Naturae with "Indian Seas" given as its type locality.[3] In 1831 Georges Cuvier classified it in the new monospecific genus Zanclus.[4] In 1876 Pieter Bleeker proposed the monotypic family Zanclidae.[5] The Zanclidae is classified within the suborder Acanthuroidei of the order Acanthuriformes.[6] Some authors classify the Moorish idols in the surgeonfish family Acanthuridae but the absence of spines on the caudal peduncle is a clear difference between this species and the surgeonfishes. Eozanclus brevirostris is an extinct species in the Zanclidae family that was first described by Giovanni Serafino Volta in 1796.[7] The species later received separate taxonomic status within the Zanclidae family through the description of Blot and Voruz in 1970 and 1975. Recently, a new extinct species has joined the Zanclidae family. The species, Angiolinia mirabilis, was described by Giorgio Carnevale and James C. Tyler in 2024 based on three specimens found in Bolca, Italy. Carnevale & Tyler found that Zanclus cornutus and Angiolinia mirabilis form a derived clade distinguishable from Eozanclus brevirostris by one supernumerary spine on the first dorsal-fin pterygiophore, one uroneural in the caudal skeleton, and distally filamentous dorsal-fin spines (except the first two fins).[8]

Etymology

[edit]Moorish idol's unusual name was apparently given to it because, in some areas of south-east Asia, fishermen have respect for these fishes, releasing them when caught and honouring them with a bow after their release.[9] In this case, Moor being erroneously used as it usually refers to Amazigh people from Morocco where this fish does not occur in the wild.[10][11] The genus name Zanclus is derived from the Ancient Greek word zanklon, meaning "sickle", and is an allusion to the long curved dorsal fin. The specific name, cornutus, means "horned", and refers to the small bony protuberances over the eyes.[12]

Description

[edit]

The Moorish idol's body is highly compressed and disc-like in shape with a tube-like snout and small bony protuberances above the eyes in adults. The mouth is small and has many long, bristle like teeth.[13] There are no spines or serrations on the preoperculum or caudal peduncle.[10] The dorsal fin is supported by 6 or 7 spines, which are elongated into a long filament which resembles a whip, and between 39 and 45 soft rays. The anal fin contains 3 spines and between 31 and 37 soft rays. The maximum published total length is 23 cm (9.1 in), although 21 cm (8.3 in) is more typical.[2] They have a white background color,[10] with two wide black vertical bands on the body with a yellow patch on the posterior end of the body and a yellow saddle on the snout.[13][10] The caudal fin is black with a white margin.[10]

Like their closely related family, the Acanthuridae, the Moorish idol has larvae that are specialized for a long pelagic life stage. In acanthuridae, the pelagic, pre-juvenile stage larvae can reach lengths of 60 mm before settling in their habitat. The Moorish idol’s various larval stages have been described and illustrated. The preflexion larval stage refers to the stage from hatchling to the start of upward flexion of the notochord.[14] The preflexion larval stage of the Moorish idol has no fin spines, soft rays, or internal support structures for the fins. However, in a 3.2 mm specimen there is the start of the dorsal and anal fins. The larger preflexion specimens have mostly cartilaginous supraoccipital crests with 23 to 26 curved dorsal spines. Also, pigmentation increases with size in the preflexion larvae.[15] The postflexion larval stage refers to the stage that includes the formation of the caudal fin and fin rays. This is the stage right before juvenile and settlement into their habitat.[14] In the postflexion stage, the Moorish idol larvae have fully developed fins, their body form is compressed and deep-bodied. The larvae have a small terminal mouth and kite shaped body. They have seven dorsal spines at the start of their dorsal fin that are covered in small spines.Their third dorsal spine is very long (about 1.2x their standard length). They also have one pelvic fin spine and three anal fin spines covered in small spines.[15]

Distribution and habitat

[edit]The Moorish idol has a wide range in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. They are found from the eastern coast of Africa between Somalia and South Africa east to Hawaii and Easter Island. They are also found in the eastern Pacific from the southern Gulf of California to Peru, including many islands such as the Galapagos and Cocos Island.[1] The Moorish idol lives between depths of 1 to 180 m in turbid lagoons, reef flats, and clear rocky and coral reefs. As with many reef fishes, habitat has been found to be an important and influential factor in the abundance of Moorish idols.[16]

Conservation Status

[edit]Since their last assessment in 2015, the Moorish idol is listed as a species of least concern by the IUCN. They were found to be widely distributed and locally abundant with no major threats to the species.[1] However, their habitat type, particularly coral reefs, are known to be in decline due to climate change. On a bright note, the species has been found to do well in restored coral reefs and artificial reef structures.[17][18]

Biology

[edit]Although, Moorish idols are omnivores, they mostly feed on sponges, as well as, algae, coral polyps, tunicates and other benthic invertebrates.[16][19][20] A gut content analysis study shows that sponges make up about 70% of the total weight consumed by Moorish idols.[20] They are normally found in small groups of 2 or 3 individuals but they can also be solitary or gather in large schools. They have a long pelagic larval stage and this is why they are so widespread and geographically uniform.[2] These fishes are pelagic spawners the males and females release sperm and eggs into the water and the eggs drift away on the current following fertilization.[19]

In the aquarium

[edit]

Moorish idols are notoriously difficult to maintain in captivity. They require large tanks, often exceeding 380 L (84 imp gal; 100 US gal),[21] are voracious eaters, and can become destructive.[21]

Some aquarists prefer to keep substitute species that look very similar to the Moorish idol. These substitutes are all butterflyfishes of the genus Heniochus and include the pennant coralfish, H. acuminatus; threeband pennantfish, H. chrysostomus and the false Moorish idol, H. diphreutes.[citation needed]

In captivity, Moorish idols typically are very picky eaters. They will either eat no food and perish, or eat everything all at once.[21]

In popular culture

[edit]- In the 2003 Disney/Pixar animated movie Finding Nemo, a Moorish idol fish named Gill, voiced by Willem Dafoe, is one of Nemo's tank mates and the leader of the Tank Gang. Gill was depicted having a very strong desire for freedom outside of the aquarium and was constantly scheming to achieve this, possibly alluding to the difficulty of keeping real-life Moorish idols in captivity. Gill and the other members of the Tank Gang appeared in the 2016 sequel, Finding Dory, in a post credits scene.[22]

- Moorish idols have long been among the most recognizable of coral reef fauna. Their image has graced all types of products, such as: shower curtains, blankets, towels and wallpaper made with an ocean or underwater theme.[citation needed]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Carpenter, K.E.; Lawrence, A. & Myers, R. (2016). "Zanclus cornutus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T69741115A69742744. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T69741115A69742744.en. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- ^ a b c Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.). "Zanclus cornutus". FishBase. February 2023 version.

- ^ Eschmeyer, William N.; Fricke, Ron & van der Laan, Richard (eds.). "Species in the genus Zanclus". Catalog of Fishes. California Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 10 July 2023.

- ^ Eschmeyer, William N.; Fricke, Ron & van der Laan, Richard (eds.). "Genera in the family Zanclidae". Catalog of Fishes. California Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 10 July 2023.

- ^ Richard van der Laan; William N. Eschmeyer & Ronald Fricke (2014). "Family-group names of recent fishes". Zootaxa. 3882 (2): 1–230. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3882.1.1. PMID 25543675.

- ^ J. S. Nelson; T. C. Grande; M. V. H. Wilson (2016). Fishes of the World (5th ed.). Wiley. pp. 497–502. ISBN 978-1-118-34233-6. Archived from the original on 8 April 2019. Retrieved 10 July 2023.

- ^ "Ittiolitologia veronese del Museo Bozziano ora annesso a quello del conte Giovambattista Gazola e di altri gabinetti di fossili veronesi - Yale University Library". collections.library.yale.edu. Retrieved 9 November 2024.

- ^ a b Carnevale, Giorgio; Tyler, James (8 February 2024). "A New Moorish Idol (Teleostei, Zanclidae) from the Eocene of Bolca, Italy". Rivista Italiana di Paleontologia e Stratigrafia. 130 (1). doi:10.54103/2039-4942/21794. ISSN 2039-4942.

- ^ "IDOLE MAURE Zanclus cornutus (Linnaeus, 1758) N° 2225". doris.ffessm.fr (in French). Retrieved 10 July 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Kenneth Wingerter (24 October 2012). "Aquarium Fish: Reconsidering the Moorish Idol". reefs.com.

- ^ Susan Scott (22 February 2016). "Common name for this fish is in need of an origin story". susanscott.net. Honolulu Star and Advertiser. Retrieved 10 July 2023.

- ^ Christopher Scharpf & Kenneth J. Lazara, eds. (12 January 2021). "Order ACANTHURIFORMES (part 2): Families EPHIPPIDAE, LEIOGNATHIDAE, SCATOPHAGIDAE, ANTIGONIIDAE, SIGANIDAE, CAPROIDAE, LUVARIDAE, ZANCLIDAE and ACANTHURIDAE". The ETYFish Project Fish Name Etymology Database. Christopher Scharpf and Kenneth J. Lazara. Retrieved 10 July 2023.

- ^ a b Bray, D.J. (2018). "Zanclus cornutus". Fishes of Australia. Museums Victoria. Retrieved 10 July 2023.

- ^ a b "The Regional Training Workshop on Larval Fish Identification and Fish Early Life History Science" (PDF). May 2007.

- ^ a b c Johnson, G. David; Washington, Betsy B. (1 May 1987). "Larvae of the moorish idol, Zanclus cornutus, including a comparison with other larval acanthuroids". Bulletin of Marine Science. 40 (3): 494–511.

- ^ a b Sluka, Robert D. "Moorish idol, Zanclus cornutus, distribution among coral reef habitats in the Republic of Maldives".

- ^ Krimou, Stéphanie; Raick, Xavier; Mery, Ethel; Carlot, Jeremy; Carpentier, Camille; Sowinski, Jérome; Sowinski, Lucille; Minier, Lana; Roux, Natacha; Maueau, Tehani; Bertucci, Frédéric; Lecchini, David (1 July 2024). "Restoring the reef: Coral restoration yields rapid impacts on certain fish assemblages". Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science. 302: 108734. Bibcode:2024ECSS..30208734K. doi:10.1016/j.ecss.2024.108734. ISSN 0272-7714.

- ^ Pulapparambil P K, Sariga, Anju; P K, Sariga; Sekharan N, Mini; Ghosh, Swagat; .B, Nidhin; Reksodihardjo-Lilley, Gayatri (3 September 2023). "Artificial Reef Deployment in North Bali, Indonesia: An Innovative Strategy to Rebuild Reef Ecosystem in Climate Change Affected Area".

- ^ a b "Moorish idol". The Dallas World Aquarium. Retrieved 21 June 2023.

- ^ a b Mortimer, Charlotte; Dunn, Matthew; Haris, Abdul; Jompa, Jamaluddin; Bell, James (19 August 2021). "Estimates of sponge consumption rates on an Indo-Pacific reef". Marine Ecology Progress Series. 672: 123–140. Bibcode:2021MEPS..672..123M. doi:10.3354/meps13786. ISSN 0171-8630.

- ^ a b c "How to Care for One of the Most Difficult Aquarium Fish". Archived from the original on 5 August 2010. Retrieved 20 March 2010.

- ^ "Willem Dafoe Returns For 'Finding Dory': 'It's Even Better Than The First'". The Inquisitr. 6 October 2013. Retrieved 6 October 2013.

External links

[edit]- Photos of Moorish idol on Sealife Collection