Young–Laplace equation

In physics, the Young–Laplace equation (/ləˈplɑːs/) is an algebraic equation that describes the capillary pressure difference sustained across the interface between two static fluids, such as water and air, due to the phenomenon of surface tension or wall tension, although use of the latter is only applicable if assuming that the wall is very thin. The Young–Laplace equation relates the pressure difference to the shape of the surface or wall and it is fundamentally important in the study of static capillary surfaces. It is a statement of normal stress balance for static fluids meeting at an interface, where the interface is treated as a surface (zero thickness): where is the Laplace pressure, the pressure difference across the fluid interface (the exterior pressure minus the interior pressure), is the surface tension (or wall tension), is the unit normal pointing out of the surface, is the mean curvature, and and are the principal radii of curvature. Note that only normal stress is considered, because a static interface is possible only in the absence of tangential stress.[1]

The equation is named after Thomas Young, who developed the qualitative theory of surface tension in 1805, and Pierre-Simon Laplace who completed the mathematical description in the following year. It is sometimes also called the Young–Laplace–Gauss equation, as Carl Friedrich Gauss unified the work of Young and Laplace in 1830, deriving both the differential equation and boundary conditions using Johann Bernoulli's virtual work principles.[2]

Soap films

[edit]If the pressure difference is zero, as in a soap film without gravity, the interface will assume the shape of a minimal surface.

Emulsions

[edit]The equation also explains the energy required to create an emulsion. To form the small, highly curved droplets of an emulsion, extra energy is required to overcome the large pressure that results from their small radius.

The Laplace pressure, which is greater for smaller droplets, causes the diffusion of molecules out of the smallest droplets in an emulsion and drives emulsion coarsening via Ostwald ripening.[citation needed]

Capillary pressure in a tube

[edit]

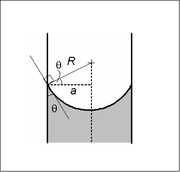

In a sufficiently narrow (i.e., low Bond number) tube of circular cross-section (radius a), the interface between two fluids forms a meniscus that is a portion of the surface of a sphere with radius R. The pressure jump across this surface is related to the radius and the surface tension γ by

This may be shown by writing the Young–Laplace equation in spherical form with a contact angle boundary condition and also a prescribed height boundary condition at, say, the bottom of the meniscus. The solution is a portion of a sphere, and the solution will exist only for the pressure difference shown above. This is significant because there isn't another equation or law to specify the pressure difference; existence of solution for one specific value of the pressure difference prescribes it.

The radius of the sphere will be a function only of the contact angle, θ, which in turn depends on the exact properties of the fluids and the container material with which the fluids in question are contacting/interfacing:

so that the pressure difference may be written as:

In order to maintain hydrostatic equilibrium, the induced capillary pressure is balanced by a change in height, h, which can be positive or negative, depending on whether the wetting angle is less than or greater than 90°. For a fluid of density ρ: where g is the gravitational acceleration. This is sometimes known as the Jurin's law or Jurin height[3] after James Jurin who studied the effect in 1718.[4]

For a water-filled glass tube in air at sea level:

and so the height of the water column is given by: Thus for a 2 mm wide (1 mm radius) tube, the water would rise 14 mm. However, for a capillary tube with radius 0.1 mm, the water would rise 14 cm (about 6 inches).

Capillary action and gravity

[edit]When including also the effects of gravity, for a free surface and for a pressure difference between the fluids equal to Δp at the level h=0, there is a balance, when the interface is in equilibrium, between Δp, the hydrostatic pressure and the effects of surface tension. The Young–Laplace equation becomes: Note that the mean curvature of the fluid-fluid interface now depends on h.

The equation can be non-dimensionalised in terms of its characteristic length-scale, the capillary length: and characteristic pressure

For clean water at standard temperature and pressure, the capillary length is ~2 mm.

The non-dimensional equation then becomes:

Thus, the surface shape is determined by only one parameter, the over pressure of the fluid, Δp* and the scale of the surface is given by the capillary length. The solution of the equation requires an initial condition for position, and the gradient of the surface at the start point.

Axisymmetric equations

[edit]The (nondimensional) shape, r(z) of an axisymmetric surface can be found by substituting general expressions for principal curvatures to give the hydrostatic Young–Laplace equations:[5]

Application in medicine

[edit]In medicine it is often referred to as the Law of Laplace, used in the context of cardiovascular physiology,[6] and also respiratory physiology, though the latter use is often erroneous.[7]

History

[edit]Francis Hauksbee performed some of the earliest observations and experiments in 1709[8] and these were repeated in 1718 by James Jurin who observed that the height of fluid in a capillary column was a function only of the cross-sectional area at the surface, not of any other dimensions of the column.[4][9]

Thomas Young laid the foundations of the equation in his 1804 paper An Essay on the Cohesion of Fluids[10] where he set out in descriptive terms the principles governing contact between fluids (along with many other aspects of fluid behaviour). Pierre Simon Laplace followed this up in Mécanique Céleste[11] with the formal mathematical description given above, which reproduced in symbolic terms the relationship described earlier by Young.

Laplace accepted the idea propounded by Hauksbee in his book Physico-mechanical Experiments (1709), that the phenomenon was due to a force of attraction that was insensible at sensible distances.[12][13] The part which deals with the action of a solid on a liquid and the mutual action of two liquids was not worked out thoroughly, but ultimately was completed by Carl Friedrich Gauss.[14] Franz Ernst Neumann (1798-1895) later filled in a few details.[15][9][16]

References

[edit]- ^ Surface Tension Module Archived 2007-10-27 at the Wayback Machine, by John W. M. Bush, at MIT OCW.

- ^ Robert Finn (1999). "Capillary Surface Interfaces" (PDF). AMS.

- ^ "Jurin rule". McGraw-Hill Dictionary of Scientific and Technical Terms. McGraw-Hill on Answers.com. 2003. Retrieved 2007-09-05.

- ^ a b See:

- James Jurin (1718) "An account of some experiments shown before the Royal Society; with an enquiry into the cause of some of the ascent and suspension of water in capillary tubes," Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, 30 : 739–747.

- James Jurin (1719) "An account of some new experiments, relating to the action of glass tubes upon water and quicksilver," Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, 30 : 1083–1096.

- ^ Lamb, H. Statics, Including Hydrostatics and the Elements of the Theory of Elasticity, 3rd ed. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 1928.

- ^ Basford, Jeffrey R. (2002). "The Law of Laplace and its relevance to contemporary medicine and rehabilitation". Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 83 (8): 1165–1170. doi:10.1053/apmr.2002.33985. PMID 12161841.

- ^ Prange, Henry D. (2003). "Laplace's Law and the Alveolus: A Misconception of Anatomy and a Misapplication of Physics". Advances in Physiology Education. 27 (1): 34–40. doi:10.1152/advan.00024.2002. PMID 12594072. S2CID 7791096.

- ^ See:

- Francis Hauksbee, Physico-mechanical Experiments on Various Subjects … (London, England: (Self-published by author; printed by R. Brugis), 1709), pages 139–169.

- Francis Hauksbee (1711) "An account of an experiment touching the direction of a drop of oil of oranges, between two glass planes, towards any side of them that is nearest press'd together," Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, 27 : 374–375.

- Francis Hauksbee (1712) "An account of an experiment touching the ascent of water between two glass planes, in an hyperbolick figure," Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, 27 : 539–540.

- ^ a b Maxwell, James Clerk; Strutt, John William (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 5 (11th ed.). pp. 256–275.

- ^ Thomas Young (1805) "An essay on the cohesion of fluids," Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, 95 : 65–87.

- ^ Pierre Simon marquis de Laplace, Traité de Mécanique Céleste, volume 4, (Paris, France: Courcier, 1805), Supplément au dixième livre du Traité de Mécanique Céleste, pages 1–79.

- ^ Pierre Simon marquis de Laplace, Traité de Mécanique Céleste, volume 4, (Paris, France: Courcier, 1805), Supplément au dixième livre du Traité de Mécanique Céleste. On page 2 of the Supplément, Laplace states that capillary action is due to "… les lois dans lesquelles l'attraction n'est sensible qu'à des distances insensibles; …" (… the laws in which attraction is sensible [significant] only at insensible [infinitesimal] distances …).

- ^ In 1751, Johann Andreas Segner came to the same conclusion that Hauksbee had reached in 1709: J. A. von Segner (1751) "De figuris superficierum fluidarum" (On the shapes of liquid surfaces), Commentarii Societatis Regiae Scientiarum Gottingensis (Memoirs of the Royal Scientific Society at Göttingen), 1 : 301–372. On page 303, Segner proposes that liquids are held together by an attractive force (vim attractricem) that acts over such short distances "that no one could yet have perceived it with their senses" (… ut nullo adhuc sensu percipi poterit.).

- ^ Carl Friedrich Gauss, Principia generalia Theoriae Figurae Fluidorum in statu Aequilibrii [General principles of the theory of fluid shapes in a state of equilibrium] (Göttingen, (Germany): Dieterichs, 1830). Available on-line at: Hathi Trust.

- ^ Franz Neumann with A. Wangerin, ed., Vorlesungen über die Theorie der Capillarität [Lectures on the theory of capillarity] (Leipzig, Germany: B. G. Teubner, 1894).

- ^ Rouse Ball, W. W. [1908] (2003) "Pierre Simon Laplace (1749–1827)", in A Short Account of the History of Mathematics, 4th ed., Dover, ISBN 0-486-20630-0

Further reading

[edit]- Maxwell, James Clerk; Strutt, John William (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 5 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 256–275.

- Batchelor, G. K. (1967) An Introduction To Fluid Dynamics, Cambridge University Press

- Jurin, J. (1716). "An account of some experiments shown before the Royal Society; with an enquiry into the cause of the ascent and suspension of water in capillary tubes". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. 30 (351–363): 739–747. doi:10.1098/rstl.1717.0026. S2CID 186211806.

- Tadros T. F. (1995) Surfactants in Agrochemicals, Surfactant Science series, vol.54, Dekker

![{\displaystyle \Delta p=\rho gh-\gamma \left[{\frac {1}{R_{1}(h)}}+{\frac {1}{R_{2}(h)}}\right]}](https://wikimedia.riteme.site/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/accaa12f17460c759fb1a1703375f5762483e9eb)

![{\displaystyle h^{*}-\Delta p^{*}=\left[{\frac {1}{{R_{1}}^{*}(h)}}+{\frac {1}{{R_{2}}^{*}(h)}}\right].}](https://wikimedia.riteme.site/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/107eb73b1a54499683156160a5dc838258fe2ed1)