Wyangala

| Wyangala New South Wales | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

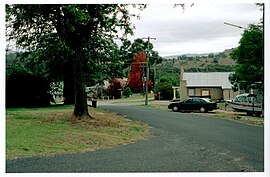

Wyangala village, looking towards St Vincent's Church (permanently closed), corner of Waugoola and Wirong Rds. | |||||||||

| Coordinates | 33°57′S 148°59′E / 33.950°S 148.983°E | ||||||||

| Population | 216 (SAL 2021)[1] | ||||||||

| Postcode(s) | 2808 | ||||||||

| Elevation | 341 m (1,119 ft)[2] | ||||||||

| Location | |||||||||

| LGA(s) | Cowra Shire | ||||||||

| County | King County | ||||||||

| State electorate(s) | Cootamundra | ||||||||

| Federal division(s) | Hume | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Wyangala /ˈwaɪæŋɡɑːlə/ is a small village in the Lachlan Valley, near the junction of the Abercrombie and Lachlan Rivers, just below the Wyangala Dam wall. It is in the South West Slopes of New South Wales, Australia, and about 320 km (200 mi) west of the state capital, Sydney. The name is also used for the surrounding rural locality, which includes the site of the former mining village of Mount McDonald.

The village was named after an indigenous word of unknown meaning, thought to be of Wiradjuri origin. The Wiradjuri were the original inhabitants of the Lachlan Valley, with campsites along river flats, on open land and by rivers. Their traditional way of life was altered, and perhaps lost, following the exploration of the valley by British explorers, John Oxley and George William Evans in 1815. White settlement followed in the 1830s, leading to violent clashes between the Wiradjuri and the settlers.

The present-day village was established in 1928, during the construction of Wyangala Dam. However, in the same area, there was a scattered pioneering settlement known as Wyangala Flats, which was established in the 1840s. This settlement was submerged under water following the completion of Wyangala Dam in 1935.

Although Wyangala grew substantially during periods of dam construction, the population dwindled in the subsequent years. This resulted in the removal of houses and the closure of most businesses, leaving Wyangala with a small primary school, a Catholic church (permanently closed), sports fields and parks, in addition to other facilities. There are no buildings of historical note, as the original purpose of the village was to solely provide utilitarian accommodation for the construction workers.

Attractions in the area include Lake Wyangala (used for power generation, water-sports and fishing activities), a nine-hole golf course, walking and mountain bike trails, and the 1.37 km (0.85 mi) long dam wall itself. Wyangala has a warm and temperate climate with a diverse range of native and exotic plants and animals, including threatened and endangered species. The flora, fauna and village residents occupy a hilly landscape dominated by granite, with large rock outcrops and boulders throughout the entire area.

History

[edit]Wiradjuri people and European settlement

[edit]Wiradjuri people were the original custodians of the region surrounding Wyangala. These skilled hunter-fisher-gatherers wore possum-skin cloaks and lived along river flats, on open ground and by rivers. They were, and still remain, the largest indigenous group in New South Wales, with tribal lands encompassing the Macquarie, the Lachlan and the Murrumbidgee rivers.[3]

Archaeological investigations have identified over 200 Wiradjuri campsites around Wyangala, suggesting the native population in the area was originally high.[4] Campsites were located on gentle hill slopes, on elevated crests and on alluvial/colluvial terraces near the Lachlan River course.[5]

The name 'Wyangala' (pronounced /ˈwaɪæŋɡɑːlə/)[6] originates from a Wiradjuri word of unknown meaning.[7] However, similar sounding words in the Wiradjuri language indicate it may mean troublesome or bad (wanggun) white (ngalar).[8] The village, situated adjacent the Lachlan River, inherited this name, as did the scattered pioneering settlement of Wyangala Flats.

On 27 May 1815, Deputy Surveyor George William Evans was the first European to discover the headwaters of the Lachlan River, naming it in honour of the NSW Governor, Lachlan Macquarie. Two years later Evans and John Oxley explored the Lachlan. They had friendly encounters with the Wiradjuri people, noting that the language they spoke was distinctly different from that used by the indigenous population on the coast.[9] By the time Oxley had reached the Cumbung Swamp, he could advance no further due to the presence of 'impassable' marshland, eventually being forced to abandon the journey and to turn back. Oxley believed he had reached a marshy inland sea, concluding that the interior of Australia was 'uninhabitable' and unfit for settlement.[10]

Despite Oxley's bleak assessment of the Lachlan Valley, European settlement of the area began several years after the expedition. In 1831 Arthur Rankin and James Sloan, both cattlemen from Bathurst, were the first white settlers to move into the Valley.[11] Encroachment on traditional Wiradjuri lands resulted in violent clashes between the indigenous population and the settlers. In the midst of this ongoing conflict, new land was made available in the Wyangala area by the colonial government. By the 1840s occupation licenses for land at Wyangala Flats were being auctioned from the Bathurst Police Office,[12] and by 1860 country lots at Wyangala were selling from the Boorowa Police Office for £1 an acre.[13] At this time and until the construction of the 1935 dam, the land at Wyangala was primarily used for wool production.[14]

The conflict with the Wiradjuri people lessened by the 1850s, as gold mining and free selection brought new settlers to the area. The unrelenting tide of Europeans overwhelmed the indigenous population, resulting in the occupation of traditional lands, the destruction of sacred sites, and perhaps most damaging of all, the introduction of new diseases. This eventually led to the displacement and the decline of the Wiradjuri people.[15][16][17]

Gold and bushrangers

[edit]

Gold mining was prevalent in the nearby Mount McDonald area in the late 1800s and early 1900s after two gold rich quartz reefs were discovered in 1880. The reefs were found by Donald McDonald and his party as they were prospecting the mountain ranges around Wyangala. McDonald happened upon the gold by chance, after seeing sunlight reflect off something beneath a tree near his camp. As news of his discovery spread, miners were drawn to the area and slowly the township of Mount McDonald 'grew in the midst of the forest'.[18] In its prime, the town had

some 600 persons living there as well as many people in the surrounding district. A school, at least one (Catholic) Church, banks, a general store... a resident doctor and the inevitable pubs.

— Frank Clune (1935)[19]

By the late 1920s, as mining declined, the town faded away.[20] Its school closed in December 1924.[21] A hamlet of no more than 4 or 5 houses exists where the Mt McDonald township once stood.

Although most of the gold mining activity was limited to Mount McDonald, alluvial gold and precious gems were also found along the banks of the Lachlan River at Wyangala in the early 1900s. However, the find was not significant enough to see commercial interest.[11][22]

The discovery of gold in other parts of New South Wales in the years prior to that found at Mount McDonald, led to increased bushranger activity. During the 1860s and 1870s the Lachlan Valley had serious problems with bushrangers, notably gangs led by Frank Gardiner, John Gilbert and Ben Hall, amongst others.[23] Frank Gardiner was one of the most successful bushrangers of the time. His final robbery, which also was to be his greatest haul, occurred in 1862 at Eugowra Rocks. In this instance, Gardiner along with Ben Hall, John Gilbert and others, robbed a 'gold escort' carrying in the range of £14,000–£22,000 in gold and cash.[20][24] It was rumored that Gardiner convinced the gang members to bury their share of the gold in a mountain cave near Wyangala.[25]

Somewhere on a rock-strewn mountain near the Fish River that empties into the Wyangala Dam, a fortune in stolen gold lies hidden.

— G.R. (1942)[25]

Gardiner was to give the gang members a signal when it was safe to recover the gold. This was never to happen, as Gardiner was eventually exiled to the United States after being sent to prison. Five years after the heist, an Irishman arrived in New South Wales with a rough map marking the location of the gold, purportedly drawn by Gardiner. Even with this map and years of searching, no trace of the gold was ever found.[25] By the late 1800s improved police efficiency was bringing to a close the era of the bushranger, many of whom had been gaoled, exiled, shot or hanged. This decline in criminal activity coincided with a general push to populate the region, the introduction of telegraph communications, and the development of transport infrastructure.[26]

20th century

[edit]By the early 1900s, unreliable river flows were stifling development in the Lachlan Valley.[27] In 1902 the Legislative Assembly of New South Wales recognised the need for water conservation. Recurrent droughts and their associated effects on waterways were impacting production and causing significant livestock deaths. The Assembly considered options to address the problem, including a proposal to build a reservoir at Wyangala. Previous surveys of the Lachlan Valley had identified Wyangala as being the only suitable location for a large water storage.[28][29] These early discussions eventually led to the construction of the 1935 dam and the beginnings of present-day Wyangala village.

1928–1935 dam construction

[edit]

To promote development in the region and to provide a reliable water supply, the Burrinjuck Dam and Wyangala Dam were constructed.[10][27] The official sod-turning ceremony to mark the beginning of the A£1.3 million project was performed by the NSW Premier, Sir Thomas Bavin, on 17 December 1928.[30] The ceremony was not conducted in the usual manner of turning over a sod of soil, it was achieved through the detonation of explosives, removing tonnes of earth and rock.[31]

The 'galvanized-iron town of Wyangala' was established to house the construction workers on land once owned by the Green family – pioneering settlers.[20] By January 1930 Wyangala had become a bustling center with 450 workers and their families in the village, and 74 children attending the new primary school.[32] In the words of a district resident

the township is progressing rapidly. The most important buildings are: One post and telegraph office, two stores, two bakers' shops, one police station, one medical practitioner, one butcher's shop, one public hall and school, one church, one boarding-house for the men employed at the works, one G.S. bank, one temporary power house, and about 40 private residences... When the dam is full the water will cover our house. I should think it will be a nice sight when completed. A new road has just been built from Woodstock to the dam. It runs through some wonderful scenery. A 32-passenger bus runs from Woodstock to the dam tri-weekly.

— Anonymous (1930)[33]

This major undertaking was not without incident. Four men died during the construction of the dam, the first being Leslie Jeffrey, falling into the Lachlan River and drowning in 1929.[34] His death was followed by that of Walter Watt, a laborer (1931), Wickliffe Brien, a dogman (1931) and Patrick Lewis, a carpenter (1933).[35][36][37][38]

The original pioneering settlement and cemetery were submerged under water after the dam was completed in 1935.[20][39]

1961–1971 dam upgrade

[edit]

Wyangala failed to hold the surging floodwaters of the devastating 1952 deluge, which was greater than any water mass it had been designed to withstand.

— Joan Marriott (1988)[14]

Due to concerns about the original dam capacity to withstand floods and a projected increase in demand for water by the agricultural industry in the region, Wyangala Dam was upgraded and enlarged from 1961 to 1971. Housing for the workers and their families was provided in temporary demountable dwellings within the village. At this time and also during the 1935 dam build, utilitarian construction prevailed, giving Wyangala no dwellings of historical note.[14]

The ten-year, A£18 million enlargement project increased the storage capacity of the dam threefold.[40] The total surface area of the upgraded reservoir was 5,390 ha (13,300 acres), storing 1,220,000 ML (43,000×106 cu ft) (two and a half times the volume of Sydney Harbour), within a catchment of 8,300 km2 (3,200 sq mi).[41][42]

The opening ceremony for the upgraded dam was scheduled to be performed by Sir Roden Cutler, Governor of NSW on 8 February 1971.[43] However, because of heavy rains and road flooding three days prior to the event, the opening was delayed until 6 August 1971. Over 2000 guests and officials attended the ceremony. In the months and years following the dam opening, the population of Wyangala decreased significantly; houses used by workers on the north-west and north-east sides of the village were removed, leaving only the houses seen in the present day village, just below the dam wall.[14]

Post office, school and church

[edit]

By March 1929, with dam construction underway (see above), up to 60 letters arrived in the village every day or two, whenever a vehicle made the trip from Cowra to Wyangala. With over 350 workers and their families already in the growing village, the lack of a post office or telegraph office was a great inconvenience to the residents.[44][45] To alleviate this issue, and to provide the residents with a reliable postal service, Wyangala Dam Post Office was opened on 14 March 1929. The newly opened post office stamped mail with a Type 2C postmark, which had a full stop after the ‘W’ of ‘N.S.W.’.[27]

Throughout the subsequent years, the village post office became an integral part of the Wyangala community, providing the expected postal and, at times, banking services (as an agent for the Commonwealth Bank of Australia). In the post-telegraph era, a manual telephone exchange was also located within the post office. The postmaster/mistress would run the telephone exchange in conjunction with running the post office. The telephone exchange was automated in the late 1980s and the post office itself was closed in 1998.[46]

Postmasters/mistresses from the 1970s until closure, included:[46]

- Ken and Peggy Bloomfield (1970s)

- Rosa and Graham Parr (1970s to early 1980s)

- Geoff and Vicki Scott (early to mid 1980s)

- Jim and Yvonne Thomas (mid 1980s to late 1980s)

- Peter Raudonkis (1990s)

Wyangala Dam Public School was established not long after the opening of the village post office, in 1929. At the time it was the district's second school. Since establishment, the school has been located at three different sites around the village. The first was near the present-day bowling club, and then near the Vic Roworth Conference Center, and finally during the 1960s, it was moved to its current location on Waugoola Road. Notably, there was an earlier school at Wyangala, which was established 22 years prior. This school ran for six years and closed in 1913.[14]

The number of children attending the school has varied widely over the years, ranging from 70+ in 1930, to 160 in the 1960s, to 20+ in the early 1980s, to under 10 in the 2000s.[14][47][48]

The first church in Wyangala was a small building made from timber and corrugated iron, built during the construction of the 1935 dam. As with the village school, it was originally located near the present-day country club, opposite the bowling green. After the dam was completed, the church was purchased by Mr Bert Priddle and transported to a property near Grenfell, where it was re-erected and licensed as an Anglican place of worship on 17 November 1935, eventually becoming consecrated by Bishop Wylde on 19 August 1953.[49][50]

The current church, St Vincent's, was built at the center of the village under the direction of Aub Murray, with interdenominational help. It is of cinder block construction, with an iron roof. The church was officially opened on 19 November 1954. The day after the opening, as preparations were being made for the first mass, a storm knocked down the rear wall of the church. Rebuilding the wall delayed the first mass until 5 December 1954.[51]

Murder

[edit]The only recorded case of a suspected murder in Wyangala village occurred in July 1935, when the coroner, Mr H. D. Pulling found the death of Mr John Neilson, a worker at the dam, was caused by a bullet wound to the head. The suspects were named as Mrs Mavis Neilsen (the victim's wife) and Mr Claude Charnock (a family friend). Both suspects claimed the shooting was accidental and self-inflicted. However, evidence from the post mortem, conducted by Dr Mahon of Cowra, and that of another witness, indicated the wound could not be self-inflicted.[52]

The suspects were charged and brought to trial in September 1935, the Crown alleging that they conspired together to kill Mr John Neilson. A short time into the trial, before the prosecution could complete their case, there was a dramatic turn of events when the jury indicated they did not wish to continue, as 'the evidence was not good enough to convict the accused'. The prosecutor appealed to the jury to wait to hear more witness and police testimony. However, after taking no more than a few seconds to consider the request, the jury members agreed there was no point continuing. Consequently, the judge acquitted both the accused and allowed them to go free.[53][54][55]

Community

[edit]Education, church hall and sport

[edit]

The village has a small one-teacher primary school, Wyangala Dam Public School, located on Waugoola Rd. Students come from the nearby rural area, the villages of Wyangala and Darbys Falls, and the Mt McDonald hamlet. The school emphasises environmental education and the creative arts.[48] As of July 2022, the school has gone into recess (non-operational) due to low enrolment numbers.[56]

Not far from the school, also on Waugoola Rd, there is a Catholic church, St Vincent's, which at times serves as a community hall for village activities. As a part of the Parish of Cowra and the Diocese of Bathurst, mass services were previously provided on alternate Saturdays and Sundays. However, as of 16 December 2023, the Catholic Diocese of Bathurst announced its permanent closure alongside two other local churches, St Malachy's, Gooloogong and St Brigid's, Woodstock.[57][58]

Adjacent the village is a nine-hole golf course, bowling green, tennis courts and cricket field. These facilities are managed by the Wyangala Country Club.[59]

In August 2013 Wyangala Cricket Oval was officially renamed Matt Morrison Oval, in honour of Matt Morrison who had died earlier in the year. Development of the Wyangala Cricket Club oval and much of the sponsorship of the Wyangala Golf Club was attributed to him.[60]

Sports clubs in Wyangala include the fishing, cricket, golf, bowling and ski clubs. The Fishing Club (Wyangala Danglers) has regular events and fishing competitions throughout the year, including inter-club competitions. The Cricket Club competes in a district cricket competition with surrounding towns including, Carcoar, Morongla, Canowindra, Grenfell and Cowra teams. The Golf Club, on the other hand, has occasional challenges and events during the year; and the Bowling Club holds regular casual meetings.[59] The Ski Club has a club house on Main Beach of Wyangala Dam and holds occasional events during the year.

Food, services and attractions

[edit]

The Wyangala Country Club, on the hillside opposite the village, has one restaurant, the Country Club Bistro, in addition to having a bar and entertainment facilities.[61] Locals congregate at the club for regular sports club meetings, for discussion forums addressing important village issues, and for other community activities.

The village Service Station/store is located at the nearby Wyangala Waters State Park entrance. The store has a range of fishing and camping supplies, in addition to take away food and other goods.[62]

Wyangala has two conference venues, the first being the Vic Roworth Conference Center within the village, and the other being the community hall in Wyangala Waters State Park. Both have seating capacities for tens of participants.[63]

There is one holiday house in the village, near Wyangala Dam Public School.[64] Additional accommodation is found at Wyangala Waters State Park, which contains numerous powered and unpowered camping sites, five bungalows, three cottages, one lodge, seven cabins and Jayco ensuite cabins.[65]

As early as the mid-1930s, Wyangala was earmarked as a major tourist attraction and important fishing ground for the Lachlan Valley.[66] The objective of turning Wyangala into a 'national playground' and resort was the vision of Reg Hailstone, a civic leader of the 1940s and 1950s.[67][68] Although Wyangala never became a 'tourist resort', Hailstone's vision for a national playground was fulfilled over the proceeding years.

Lake Wyangala (the impounded reservoir within the Dam) is a significant and popular inland fishing location. Through the spring and summer seasons, Lake Wyangala is also used for various water sports, such as canoeing, jet-skiing, sailing, swimming and water skiing. There are walking and mountain bike trails through bushland near the village and the State Park, and houseboat hire is available for those seeking the opportunity to explore the lake and catch fish. Waterslides located within the Park are currently not operating.[69] Dissipater Park, just below the Dam wall, has BBQ facilities for picnics and other gatherings.[70]

The 1.37 km (0.85 mi) long Dam wall is a notable landmark in the Lachlan Valley. It is 85 m (279 ft) high (as tall as a 25-story building),[41] and has a width at its base of 304 m (997 ft).[71] It can be viewed from various locations around the village and from nearby lookouts, as well as from many kilometers away on Darbys Falls Road. Historically, it was possible to drive across the top of the wall. However, as of June 2014, vehicle access was closed following the completion of an alternative access road (Trout Farm Road) and bridge downstream of the village.

Geography

[edit]Location and demographics

[edit]

Wyangala is situated in the Australian state of New South Wales, approximately 320 km (200 mi) west of Sydney. It lies in an area known as the South West Slopes, a region extending from north of Cowra, through southern New South Wales, and down into western Victoria.

The Wyangala population dropped from 227 in the 2011 census[72] to 182 in the 2016 census.[73] At the 2021 census the population of Wyangala had increased to 216.[74]

In 2016 the population comprised 42.8% females and 57.2% males, with an average age of 57 years, 19 years above the Australian average. 77.7% of people living in Wyangala were born in Australia. Other countries of birth included England 4.0%, New Zealand 2.3% and Scotland 2.3%. The religious make up was Anglican 30.3%, No Religion 24.0%, Catholic 23.4%, and Uniting Church 4.6%.

65.6% of the people living in Wyangala were employed full-time, and 18.8% were working on a part-time basis. The unemployment rate was 6.2%, 0.7% below the national average of 6.9%. The main occupations of people from Wyangala were Managers 28.8%, Clerical and Administrative Workers 16.9%, Labourers 11.9%, Technicians and Trades Workers 11.9%, Machinery Operators And Drivers 11.9%, Sales Workers 8.5%, Professionals 5.1%, Community and Personal Service Workers 5.1%. The median rent in Wyangala was $100 per week and the median mortgage repayment was $910 per month.[73]

Water resources

[edit]The Lachlan Valley is a region of New South Wales (NSW), which extends from Crookwell in the east, to Oxley in the west of the state. It covers a catchment area of 84,700 km2 (32,700 sq mi), making up 10% of NSW.[75] The area accounted for 14% of the state's agricultural production in 2005. Lake Wyangala is the only major water storage within the Valley — supplying water to over 88,000 ha (220,000 acres) of irrigated land.[40] In addition to what is used by agricultural irrigators and horticulturalists, water from the reservoir is used for general industry, mining industries, recreational purposes, stock and domestic supplies, town water supply and aquatic habitat protection.[76][77]

A hydro-electric power station is located below the Wyangala Dam wall, beside the village, at Dissipater Park. It generates an average output of 42.9 gigawatt-hours (154 TJ) per annum. This is enough electricity to supply almost 6400 three-person households in the area, assuming 6,723 kWh (24,200 MJ) per household per year.[78]

Biota, geology and climate

[edit]Wyangala has a diverse range of native and exotic plants and animals, including vulnerable, threatened and endangered species. Flora and fauna found in and around the village include:[79][80][42]

The aforementioned plant and animal species inhabit the geological subdivision known as the Lachlan Fold Belt. It is a zone folded and faulted with Early Silurian Wyangala Granite, which has intruded passively, deformed Ordovician greywackes and volcaniclastics.[81][82]

The local Wyangala landform is characterised by granite rock outcrops and large boulders, scattered throughout a hilly landscape. This contributes greatly to the soils of the area, which are largely formed from the weathering of granite. They include fragile, shallow stony soils on the steep slopes, to naturally acidic and sodic soils on the lower slopes. These soils are prone to degradation issues, and are susceptible to erosion, nutrient loss and salinity.[79]

The climate is warm and temperate in Wyangala, with significant rainfall throughout the year. According to Köppen climate classification it is classified as Cfa. The average annual temperature in Wyangala is 15.2 °C (59.4 °F), and it receives about 600 mm (24 in) precipitation. The warmest month of the year is January with an average temperature of 23.9 °C (75.0 °F). In July, the average temperature falls to 7.9 °C (46.2 °F), the lowest average temperature of the whole year.[83]

The difference in precipitation between the driest month and the wettest month is 17.5 mm (0.69 in). Average temperatures vary during the year by 16 °C (61 °F).[83]

Recent times

[edit]Earthquake

[edit]In October 2006 a magnitude 4 earthquake was felt throughout the New South Wales Central West, with the epicenter at Wyangala.[84] An earthquake of this magnitude is classified as Light on the Richter scale and usually results in noticeable shaking of indoor objects and rattling noises. The State Water Corporation examined Wyangala Dam to see if it bore damage, finding that pressure and seepage gauges were unaffected by the earthquake.[85] In addition, no damage or injuries were reported within the village or the State Park.

Dam wall road closure

[edit]

In 2009 NSW State Water Corporation announced plans to permanently close public road access over Wyangala Dam wall, because of the introduction of 'tough new security measures' and to comply with occupational health and safety requirements. This new policy was to coincide with a significant upgrade and increase in height of the Dam wall.[86] State Water proposed that alternative access be provided to Wyangala via Mt McDonald Road.[87] This announcement angered locals, as they believed the implications of such a change had not been considered. Concerns included:[88]

- Access to Wyangala Dam Public School, where children would need to travel 60 km (37 mi) to get to school and back, instead of having a 5 km (3.1 mi) journey

- Local workers on the 'wrong' side of the dam wall not being able to make the long detour via Mt McDonald Rd

- The dangers of the narrow curves and bends on Mt McDonald road

- Access time and ease of access for emergency services vehicles to Wyangala

- The possible decline in patronage of Wyangala Waters State Park and Wyangala Country Club (it is estimated over 75% of visitors enter Wyangala via the Dam wall road)

The concerns voiced by local citizens, emergency services and local councils resulted in a review of the decision to reroute traffic through Mt McDonald road. Subsequently, a report prepared by Ian Armstrong recommended that a bridge be built across the Lachlan River, downstream of the village to give alternate access to Wyangala. This recommendation was accepted by most locals as the only viable option, even though there was dissent from people affected by the new road and bridge.[89][90]

In June 2014, the bridge (Wyangala Bridge) and new road (Trout Farm Road) were completed.[91]

Removal of waterslides

[edit]At the beginning of 2013 Wyangala Waters State Park advertised for expressions of interest to remove the water slides from within the Park. The slides had not been in use due to problems of Park management finding a suitable operator. This unexpected announcement by the Park resulted in an extensive campaign to save the slides.[92]

Following the public outcry, the former NSW Deputy Premier, Andrew Stoner, put on hold plans to remove the slides, and moving forward, to appoint a group to review the slides future. This decision was welcomed by locals and the shire mayor, Bill West, who considered the slides "a very important tourist attraction ... and popular part of Cowra Shire".[93] No decision has been made regarding the future of the slides.

Closure of school

[edit]In 2015, only 5 students were attending Wyangala Dam Public School. This significant decline in numbers was attributed to the ageing population of the Wyangala community and the lack of any new young families within the village and surrounding area. Consequently, the school was at risk of closure if student numbers did not increase. A meeting to discuss the future of schooling within the village was held on 23 June 2015 with the Director of Public Schools Orange Network, allowing village residents and current and former students to ask questions and to present the case for keeping the school open. Any decision by the NSW Department of Education and Training regarding the schools future is to be decided at some future date, not yet determined. In 2015, village residents created a working group to launch a campaign to attract new students to the school, this campaign continued for a number of years.[94][95][96] Despite village efforts, the school is at present non-operational due to low enrolment numbers (see community section).

Fuel service

[edit]In May 2018, fuel supply services at Wyangala, along with several other inland waterways, were closed due to health and safety concerns and a need to upgrade existing facilities.[97] Visitors were also banned from carting in their own fuel until a storage and management solution was devised, forcing them to refuel at nearby Cowra.[98] After a brief tender period, by October 2018, Penrith-based firm Petrolink Engineering was selected to replace the existing fuel facilities. Although their intent was to get fuel facilities back in place before Christmas 2018,[99] they were not restored until February 2019.[100]

Raising dam wall height

[edit]In 2018, former New South Wales Minister for Primary Industries and Regional Water, Niall Blair proposed increasing the height of the Wyangala Dam wall by 10 m (33 ft) "to give greater water security for residents and farmers along the Lachlan River."[101] The change in height was intended to increase storage by 50% and provide increased capacity during flood events.[102] In addition to the direct costs of the enlargement, current camping areas and other infrastructure were to be moved, due to higher water levels once works were completed.[103]

In October 2019, A$650 million was allocated to raising the dam wall by the previously suggested height of 10 m (33 ft). This 650 GL (2.3×1010 cu ft) increase in dam storage was to be funded 50-50 by the State and Federal governments of Australia. The Deputy Prime Minister (Member for Riverina) Michael McCormack at the time said "the project was a significant investment for the future", helping secure water supplies during times of drought. Work was to begin in 2020 and was expected to be completed by 2025.[104]

As of October 2023, the proposed upgrade has been cancelled due to increased costs and environmental concerns.[105]

References

[edit]- ^ Australian Bureau of Statistics (28 June 2022). "Wyangala (suburb and locality)". Australian Census 2021 QuickStats. Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- ^ "Elevation of 12 13 Winga Road Wyangala NSW 2808". elevationmap.net. Archived from the original on 17 May 2014. Retrieved 1 May 2014.

- ^ "Indigenous objects from Peak Hill, NSW – The Australian Museum". Australian Museum. Archived from the original on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- ^ English, A.J. & Gay, L.M. (1995). Archaeological Survey and Assessment of Aboriginal Sites, Wyangala Catchment, NSW. Report prepared for Project Steering Committee.

- ^ Jodie Benton; Kim Tuovinen; Emily McCuistion (2013). Aboriginal and Historic Heritage Assessment, Kempfield Project. OzArk Environmental and Heritage Management P/L. p. 32.

- ^ "Automatic Phonemic Transcriber". Tom Brøndsted. Archived from the original on 24 April 2014. Retrieved 1 May 2014.

- ^ "Wyangala Dam". Geographical Names Register (GNR) of NSW. Geographical Names Board of New South Wales. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- ^ "Sydney Aboriginal Languages and Computing". Human Services, Aboriginal Affairs, NSW. Archived from the original on 12 October 2014. Retrieved 1 May 2014.

- ^ "Journals of Two Expeditions into the Interior of New South Wales, by John Oxley". University of Adelaide. Archived from the original on 14 April 2014. Retrieved 1 May 2014.

- ^ a b "Possibilities of the Lachlan Valley". The Land. Sydney. 25 July 1924. p. 2. Retrieved 24 April 2014 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ a b "Cowra". The Sydney Morning Herald. 8 February 2004. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- ^ "OCCUPATION LICENSES". The Sydney Morning Herald. 9 February 1844. p. 4. Retrieved 24 April 2014 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "CROWN LANDS' SALES". Goulburn Herald. NSW. 10 March 1860. p. 3. Retrieved 24 April 2014 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ a b c d e f Joan Marriott (1988). Cowra on the Lachlan. Cowra Shire Council and Cowra and District Historical Society. pp. 172–191, 235–238.

- ^ "The Wiradjuri People". Bathurst Heritage Matters. Archived from the original on 6 March 2014. Retrieved 1 May 2014.

- ^ "Wiradjuri". Will Carter Art. Archived from the original on 29 May 2014. Retrieved 1 May 2014.

- ^ "South Western Slopes – regional history". Environment and Heritage, NSW Government. Archived from the original on 18 August 2014. Retrieved 1 May 2014.

- ^ "MOUNT MACDONALD GOLDFIELD, NEW SOUTH WALES". The Argus. Melbourne. 5 October 1881. p. 10. Retrieved 24 April 2014 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Mount McDonald – Early Days". Frank Murray. Archived from the original on 28 February 2014. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

- ^ a b c d Frank Clune (1944). Rolling Down the Lachlan. Moderne Printing Co. pp. 92–116.

- ^ "Mount McDonald". nswgovschoolhistory.cese.nsw.gov.au. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

- ^ "PRECIOUS STONES". The Maitland Daily Mercury. NSW. 25 May 1923. p. 3. Retrieved 24 April 2014 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Bushrangers". National Museum of Australia. Archived from the original on 15 April 2014. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- ^ "FRANK GARDINER". The Capricornian. Rockhampton, Qld. 14 October 1905. p. 27. Retrieved 30 May 2014 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ a b c "EUGOWRA GOLD ESCORT ROBBERY". The Grenfell Record and Lachlan District Advertiser. NSW. 11 June 1942. p. 1. Retrieved 12 May 2014 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "BUSHRANGERS OF AUSTRALIA" (PDF). National Museum of Australia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 September 2007. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ^ a b c "Wyangala Dam Constructed on the Lachlan River". Australian Postal History and Social Philately. Archived from the original on 23 March 2014. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

- ^ "WATER CONSERVATION". The West Australian. Perth. 20 June 1902. p. 5. Retrieved 24 April 2014 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "PRIVATE IRRIGATION". The Sydney Evening News. 6 May 1903. p. 4. Retrieved 24 April 2014 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "WYANGALA DAM". The Sydney Morning Herald. 3 December 1928. p. 7. Retrieved 24 April 2014 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "THE LACHLAN VALLEY". The Sydney Morning Herald. 11 April 1931. p. 9. Retrieved 10 May 2014 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "WYANGALA DAM". The Sydney Morning Herald. 7 January 1930. p. 8. Retrieved 30 April 2014 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Wyangala Dam and Town". The Land. Sydney. 30 May 1930. p. 19. Retrieved 28 April 2014 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "WORKMAN DROWNED". The Maitland Weekly Mercury. NSW. 23 February 1929. p. 6. Retrieved 24 April 2014 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "WYANGALA FATALITY". Western Champion. Parkes, NSW. 7 December 1931. p. 7. Retrieved 24 April 2014 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Berlin More Prosperous". Carcoar Chronicle. NSW. 4 December 1931. p. 4. Retrieved 24 April 2014 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Wyangala Compensation Case". Carcoar Chronicle. NSW. 23 September 1932. p. 1. Retrieved 7 June 2014 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Carpenter's Fatal Fall". The Advertiser. Adelaide. 29 November 1933. p. 14. Retrieved 24 April 2014 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Science Tour 1". Central NSW Tourism. p. 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 March 2014. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

- ^ a b "Environmental Effects of Wyangala Dam". Murray-Darling Freshwater Research Centre. p. iii. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 August 2014. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- ^ a b "Wyangala Dam". State Water Corporation. Archived from the original on 27 April 2014. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- ^ a b "Wyangala Waters". NSW Gov., Trade and Investment, Crown Lands. Archived from the original on 5 March 2014. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

- ^ "Dam to open". The Canberra Times. 20 January 1971. p. 19. Retrieved 24 April 2014 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "WYANGALA WEIR". The Burrowa News. NSW. 8 March 1929. p. 1. Retrieved 24 April 2014 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "WYANGALA WEIR". Goulburn Evening Penny Post (DAILY and EVENING ed.). NSW. 1 March 1929. p. 6. Retrieved 24 April 2014 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ a b Vicki Scott (2014). Recollections of a Wyangala Dam Post Office Postmistress.

- ^ "WYANGALA DAM". Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners' Advocate. NSW. 7 January 1930. p. 4. Retrieved 8 August 2014 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ a b "Going to a Public school". NSW Government Education and Communities. Archived from the original on 17 March 2014. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

- ^ "Anglican News: Reporting for the Church in Western New South Wales". Bathurst Anglican Diocese. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 September 2014. Retrieved 1 September 2014.

- ^ "Anglican News in 3D" (PDF). Bathurst Anglican Diocese. December 2012. Archived from the original on 10 March 2015. Retrieved 1 November 2014.

- ^ John Cooke; Bernie Sheehy (2014). Wyangala Dam Church.

- ^ "WYANGALA". The Sydney Morning Herald. 9 July 1935. p. 11. Retrieved 24 April 2014 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "MURDER CHARGE FAILS". Advocate (DAILY ed.). Burnie, Tasmania. 3 September 1935. p. 7. Retrieved 24 April 2014 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "UNEXPECTED ENDING". The Northern Miner. Charters Towers, Qld. 3 September 1935. p. 3. Retrieved 24 April 2014 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "ACQUITTED". Goulburn Evening Penny Post (DAILY ed.). NSW. 3 September 1935. p. 1. Retrieved 24 April 2014 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Wyangala Dam Public School Newsletter Term 2 Week 10 2022" (PDF). Wyangala Dam Public School. Retrieved 18 January 2024.

- ^ "St Raphael's Parish Cowra". Catholic Diocese of Bathurst. Archived from the original on 17 March 2014. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

- ^ "Catholic Churches In Gooloogong, Woodstock And Wyangala To Close Permanently". The Cowra Phoenix. Retrieved 13 January 2024.

- ^ a b "About Us". Wyangala Country Club. Archived from the original on 22 December 2014. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

- ^ "Club News". Wyangala Country Club. Archived from the original on 17 March 2014. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

- ^ "Wyangala Dam Bistro". Wyangala Dam Country Club. Archived from the original on 24 March 2014. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

- ^ "General Store and Service Station". Wyangala Waters State Park. Archived from the original on 10 March 2016. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

- ^ "Community Hall". Wyangala Waters State Park. Archived from the original on 10 March 2016. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- ^ "Wyangala Waters Holiday House". Cowra Tourism Corporation. Archived from the original on 24 January 2014. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

- ^ "Accommodation Information". Wyangala Waters State Park. Archived from the original on 10 March 2016. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

- ^ "WYANGALA DAM". The Burrowa News. NSW. 30 November 1934. p. 3. Retrieved 24 April 2014 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "As National Playground". The Burrowa News. NSW. 15 February 1946. p. 2. Retrieved 24 April 2014 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Wyangala Dam—Tourist Resort of the Central West?". The Burrowa News. NSW. 24 May 1946. p. 1. Retrieved 24 April 2014 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Attractions". Wyangala Waters State Park. Archived from the original on 10 March 2016. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

- ^ "Wyangala". Cowra Tourism. Archived from the original on 28 February 2015. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

- ^ "Dam Information". Wyangala Waters State Park. Archived from the original on 10 March 2016. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- ^ "2011 Census QuickStats: Wyangala". Australian Bureau of Statistics. Archived from the original on 17 May 2014. Retrieved 1 May 2014.

- ^ a b "2016 Census QuickStats: Wyangala". Australian Bureau of Statistics. Archived from the original on 29 July 2018. Retrieved 13 December 2018.

- ^ "2021 Wyangala, Census All persons QuickStats". Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 16 August 2022.

- ^ "About The Lachlan". Lachlan Valley Water. Archived from the original on 18 May 2014. Retrieved 1 May 2014.

- ^ New South Wales Department of Land and Water Conservation & Lachlan Catchment Management Board (2003). Lachlan Catchment Blueprint. Sydney, Lachlan Catchment Management Board.

- ^ "Benchmarking social attitudes to river health and carp management" (PDF). NSW Government, Industry and Investment. October 2009. p. 4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 April 2014. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- ^ "Average household electricity usage". Energy Made Easy, Australian Government. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- ^ a b "Wyangala Alternative Access Report" (PDF). State Water. October 2011. pp. 36–49. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 May 2013. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

- ^ "LOT 156 Mount Darling Road, Wyangala NSW 2808, Australia". The Atlas of Living Australia. Archived from the original on 29 March 2014. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- ^ Paul Lennox; Helga de Wal; Karol Czarnota; Lloyd White (2008). Preliminary results from AMS studies of the deformed Wyangala Granite, Cowra, New South Wales, Australia. Vol. 95. Geotectonic Research. pp. 97–99.

- ^ Axel Müller; Paul Lennox; Robert Trzebski (2002). Cathodoluminescence and micro-structural evidence for crystallisation and deformation processes of granites in the Eastern Lachlan Fold Belt (SE Australia). Vol. 143. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology. pp. 510–524.

- ^ a b "Climate History: Wyangala Dam". Meat and Livestock Australia. Archived from the original on 21 May 2014. Retrieved 1 May 2014.

- ^ "Quake hits central west NSW". ABC News. 21 October 2006. Archived from the original on 26 April 2014. Retrieved 1 June 2014.

- ^ "Recent quakes not 'too far outside the norm'". ABC News. 23 October 2006. Archived from the original on 26 April 2014. Retrieved 1 June 2014.

- ^ "Concerns aired over dam road closure". ABC News. 17 March 2009. Archived from the original on 19 March 2014. Retrieved 1 June 2014.

- ^ "Road across Wyangala Dam wall to close". ABC News. 10 March 2009. Archived from the original on 19 March 2014. Retrieved 1 June 2014.

- ^ "Meeting to debate Wyangala road closure plan". ABC News. 24 March 2009. Archived from the original on 19 March 2014. Retrieved 1 June 2014.

- ^ "Doubt cast over dam road upgrades". ABC News. 19 March 2010. Archived from the original on 19 March 2014. Retrieved 1 June 2014.

- ^ "Wyangala access route bringing opportunities". ABC News. 18 May 2011. Archived from the original on 19 May 2014. Retrieved 1 June 2014.

- ^ "Two residents are concerned with Wyangala's Trout Farm Road upgrade". Cowra Guardian. 24 June 2014. Archived from the original on 29 October 2014. Retrieved 1 June 2014.

- ^ "Campaign begins to save Wyangala's water slides". Cowra Guardian. 18 February 2013. Archived from the original on 19 March 2014. Retrieved 1 June 2014.

- ^ "State back down from Wyangala waterslides' removal". ABC News. 28 February 2013. Archived from the original on 19 March 2014. Retrieved 1 June 2014.

- ^ "Community meeting to decide future of Wyangala school". Cowra Guardian. 15 June 2015. Archived from the original on 30 June 2015. Retrieved 1 June 2015.

- ^ "Wyangala Dam School under threat of closure". Cowra Community News. 18 June 2015. Archived from the original on 30 June 2015. Retrieved 1 June 2015.

- ^ "Numbers game: future of Wyangala school hangs in balance". Cowra Guardian. 26 June 2015. Archived from the original on 30 June 2015. Retrieved 1 June 2015.

- ^ "Fuel Tank Closures from Today for Inland Park Infrastructure Upgrades". Medianet. 29 May 2018. Archived from the original on 25 January 2019. Retrieved 25 January 2019.

- ^ "Under the pump: No boat fuel allowed at Wyangala, Burrendong". Central Western Daily. 31 May 2018. Archived from the original on 25 January 2019. Retrieved 25 January 2019.

- ^ "No fuel service at Wyangala Dam until the end of January". Cowra Guardian. 19 December 2018. Archived from the original on 25 January 2019. Retrieved 25 January 2019.

- ^ "Fuel service restored at Wyangala Dam". Cowra Guardian. 21 February 2019. Archived from the original on 24 February 2019. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- ^ "Blair puts raising Wyangala Dam wall firmly on the table". Parkes Champion-Post. 1 November 2018. Archived from the original on 15 December 2018. Retrieved 13 December 2018.

- ^ "Water security a priority in decision to raise Wyangala Dam wall". Cowra Guardian. 30 October 2018. Archived from the original on 15 December 2018. Retrieved 13 December 2018.

- ^ "Opinion: Wyangala Dam proposal is only a proposal". Cowra Guardian. 5 November 2018. Archived from the original on 16 December 2018. Retrieved 13 December 2018.

- ^ "$650 million Wyangala Dam wall upgrade to secure water for Lachlan region, adding 650 gigalitres to capacity". Central Western Daily. 14 October 2019. Retrieved 4 November 2019.

- ^ "Wyangala Dam Wall Raising Project cancelled due to cost and environmental concerns". International Water Power. 17 October 2023. Retrieved 18 January 2024.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Wyangala at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Wyangala at Wikimedia Commons