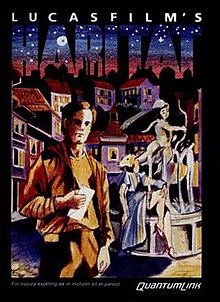

Habitat (video game)

| Habitat | |

|---|---|

| |

| Developer(s) | Lucasfilm Games Quantum Link Fujitsu |

| Publisher(s) | Quantum Link Fujitsu |

| Director(s) | Chip Morningstar[3] |

| Producer(s) | Steve Arnold[3] |

| Designer(s) | Chip Morningstar[3] Randy Farmer |

| Programmer(s) | Chip Morningstar[3] Randy Farmer[3] Aric Wilmunder[3] Janet Hunter[3] |

| Artist(s) | Gary Winnick[3] |

| Platform(s) | Commodore 64, FM Towns, Microsoft Windows, Mac OS |

| Release |

|

| Genre(s) | Massively multiplayer online role-playing game |

| Mode(s) | Multiplayer |

Habitat is a massively multiplayer online role-playing game (MMORPG) developed by LucasArts. It is the first attempt at a large-scale commercial virtual community[4][5] that was graphic based. Initially created in 1985 by Randy Farmer, Chip Morningstar,[6] Aric Wilmunder and Janet Hunter, the game was made available as a beta test in 1986 by Quantum Link, an online service for the Commodore 64 computer and the corporate progenitor to AOL. Both Farmer and Morningstar were given a First Penguin Award at the 2001 Game Developers Choice Awards for their innovative work on Habitat. As a graphical MUD[7] it is considered a forerunner of modern MMORPGs unlike other online communities of the time (i.e. MUDs and massively multiplayer onlines with text-based interfaces). Habitat had a GUI and large user base of consumer-oriented users, and those elements in particular have made Habitat a much-cited project and acknowledged benchmark for the design of today's online communities that incorporate accelerated 3D computer graphics and immersive elements into their environments.

Culture

[edit]Habitat is "a multi-participant online virtual environment", a cyberspace. Each participant ("player") uses a home computer (Commodore 64) as an intelligent, interactive client, communicating via modem and telephone over a commercial packet-switched network to a centralized, mainframe computer. The client software provides the user interface, generating a real-time animated display of what is going on and translating input from the player into messages to the host. The host maintains the system's world model enforcing the rules and keeping each player's client informed about the constantly changing state of the universe.

— Farmer 1993

Users in the virtual world were represented by onscreen avatars,[8][4][9] meaning that individual users had a third-person perspective of themselves, making it rather like a videogame. Players in the same region (denoted by all objects and elements shown on a particular screen) could see, speak (through onscreen text output from the users), and interact with one another. Habitat was governed by its citizenry. The only off-limits portions were those concerning the underlying software constructs and physical components of the system. The users were responsible for laws and acceptable behavior within Habitat. The authors of Habitat were greatly concerned with allowing the broadest range of interaction possible, since they felt that interaction, not technology or information, truly drove cyberspace.[4] Avatars had to barter for resources within Habitat, and could even be robbed or "killed" by other avatars. Initially, this led to chaos within Habitat, which led to rules and regulations (and authority avatars) to maintain order.

Timeline

[edit]Randy Farmer, Chip Morningstar, Aric Wilmunder and Janet Hunter created the first graphical virtual world, which was released in a beta test by Lucasfilm Games in 1986 as Habitat for the Quantum Link service for the Commodore 64.[10] Habitat ran from 1986[8] to 1988, and was closed down at the end of the pilot run. The service proved too costly to be viable, so Lucasfilm Games recouped the cost of development by releasing a sized down version called Club Caribe on Quantum Link in 1988.[11] It was then licensed by Fujitsu in 1988,[12] and released in Japan as Fujitsu Habitat in 1990.

In 1994, Fujitsu Cultural Technologies was spun off as a new division of Fujitsu Open Systems Solutions, INC or OSSI for short. In conjunction with Electric Communities, the two companies began work on the WorldsAway project (which was codenamed "Reno" at the time).[13] Originally, the initial plan was for the team to work from the Fujitsu Habitat code and bring it to the Mac and Windows operating systems.[12] This proved not to be possible due to the fact the underlying architecture was nothing like its predecessor Habitat due to being developed by a different team. This led to delays in the project whilst the kinks were being worked out.[14] It was launched on CompuServe in 1995 as a free service for members.[15] The world was called Dreamscape[16] and moved to the public Internet in 1997 still under the operation of Fujitsu. As CompuServe morphed into AOL's "value brand", Fujitsu sought to sell off its product as they were making a loss. Inworlds.com (who later became Avaterra, Inc) stepped up and bought the licensing rights and took over the reins. In 2011 the Dreamscape was still surviving independently as one of the VZones.com worlds – owned by Stratagem Corporation. Other WorldsAway worlds using the same server software that have been launched during Stratagem times were newHorizone, Seducity, Second Kingdom and Datylus.[17] The VZones.com worlds closed in August 2014. The only remaining licensees of the technology is vzones.com.

Creation

[edit]One challenge in producing games is to resist the "conceit that all things may be planned in advance and then directly implemented according to the plan's detailed specification". Morningstar and Farmer argue that this mentality only leads to failure as the potential capabilities and imagination of a game would remain confined within the small niche of developers. They generalized this well by pointing out that "even very imaginative people are limited in the range of variation that they can produce, especially if they are working in a virgin environment uninfluenced by the works and reactions of other designers".[18]

An example of this approach was when Wilmunder, the programmer responsible for developing both backgrounds for the Habitat World and Avatar animations noted how the original specification only included a single generic male and female character. Wilmunder determined that the system could go further and he implemented the ability to customize player Avatars, first by patterning their clothing, and later allowing Avatars to change height, carry items, and ultimately to allow the players to select from over one hundred different heads for their characters, capabilities that are today taken for granted in other Avatar based systems. This feature became so popular that 'heads' were sold in in-game vending machines and were even used as rewards for players when they completed quests.

With this outlook, Morningstar and Farmer stated that a developer should consider providing a variety of possible experiences within the cyberspace, ranging from events with established rules and goals (i.e. hunts) to activities propelled by the user's own motivations (entrepreneur) to completely free-form, purely existential activities (socializing with other members). The best method to manage and maintain such an immense project, they have discovered, was to simply to let the people drive the direction of design and aid them in achieving their desires. In short the owners became the facilitators as much as designers and implementers.

Regardless, the authors note the importance of separation between the access levels of the designer and the operator. They classify the two coexisting virtualities as the "infrastructure level" (implementation of the cyberspace, or the "reality" of the world), which the creators should only control, and the "experiential level" (visual and interactive feature for users), which the operators are free to explore. The user not need to be aware of how data are encoded in the application. This naturally follows from the good programming practice of encapsulation.[19]

Revival

[edit]In 2016, a project was undertaken to relaunch Habitat using emulation of both the Commodore 64 and the original Q-Link system that Habitat ran on.[20] The project was headed by Alex Handy, founder of The Museum of Art and Digital Entertainment (MADE), who received the game's source code from its original developers.[21] That July, the source code was uploaded by MADE to GitHub under MIT license for open review.[22][23]

In February 2017, an open-source project to revive Habitat led by Randy Farmer (one of Habitat's creators) named NeoHabitat was announced to the public. The project was requesting volunteer contributors to aid in developing code, region design, documentation and provide other assistance. Due to the volunteer contributors, original source files, maps created during development and database backups were unearthed. This enabled the original Populopolis world to be fully restored. NeoHabitat is currently operational and accessible to all. Development is mostly complete and the original Habitat experience can be had once more.[24]

WorldsAway

[edit]WorldsAway was launched in 1995 and was developed by some of the Habitat team, although no code is shared between the two projects. WorldsAway is an online graphical "virtual chat"[25] environment in which users designed their own two dimensionally represented avatars.[26][27] It was one of the first visual virtual worlds.[25] In 1996 it was one of the top 20 most popular forums on Compuserve.[28] WorldsAway users would login, originally through dial-up Compuserve accounts and later through the Internet. First-time users would choose their gender, name, head and body style on a virtual ship before entering the world proper to meet other online users (these could be changed later by paying a quantity of tokens).[29]

Each subscriber would view and manipulate their own avatar which was displayed in a limited set of poses and profiles.[27] A user would walk their avatar around a virtual city (named Kymer), enter shops and teleporter cabins, gesture or chat to other avatars (cartoon like text bubbles would appear), and carry out various in-game actions.[25][27] Ty Burr's 1996 review of the three graphical chat worlds then available (the others were Worlds Chat and Time Warner's The Palace) rated WorldsAway the lowest at C+, criticizing the slowness and lack of flexibility.[25]

Unlike some modern virtual worlds, WorldsAway did not boast 3D graphics or any combat system (although inworld combat had been planned, it was never implemented).[30] Most time spent in the world by users was spent on economic endeavors and chat. This meant that the world had a monetary token system and virtual business endeavors could be set up such as Clover's famous auctions with commissions for sales, or Dennis S's nightclub with admission charges, or the payments for the various street games such as bingo. The token system facilitated the economy. Avatars received tokens based on the number of hours played, from sales of objects, from gifts, and other sources such as running enterprises. Rare and/or functional objects were introduced into the world by stores and Acolytes. Acolytes were appointed by the Oracles and had access to changing supplies of objects that they gave away or awarded as prizes to the community. Clover's famous auctions were held weekly and people bid vast amounts of tokens to acquire rare items such as heads, clothing, furniture, and other useful or artistic objects. Apartments could be purchased, furnished, or sold. Other popular past-times were playing Bingo[25] and other simple games. These games were not a part of the original software, but were made by third party developers as plug-ins.[30]

Dreamscape

[edit]Dreamscape was the first graphical online chat environment built on the WorldsAway platform. It allowed users to create an avatar to represent themselves in a 2D world and interact with other users and virtual items.[31] The player chooses an avatar, which is the graphical representation of the player. The avatar can text chat, move, gesture, use facial expressions, and is customizable in a virtually unlimited number of ways. Avatars earn money, own possessions, rent apartments, and make friends. The environment itself is composed of thousands of screens, in which the player's avatar moves about.[6]

Popular culture

[edit]Much of the second and third seasons of the American TV series Halt and Catch Fire is centered around the development and troubles of the fictional tech startup Mutiny, heavily inspired by the story of PlayNET and Quantum Link in the 1980s.[32] In the show, Mutiny transitions from an online games company to eventually delivering an online subscriber-based graphical chat community for Commodore 64 users, mirroring Habitat.[33]

Reception

[edit]Roy Wagner reviewed the game for Computer Gaming World, and wrote that "this game effectively optimizes the local storage, processing and graphics power of the low cost Commodore 64/128 home computer that is in over four million homes and the real-time, person-to-person, interactivity made possible by a low cost nationwide network that is accessible with a local phone call".[34]

Reviews

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "The Lessons of Lucasfilm's Habitat".

- ^ "The Game Archaeologist moves into Lucasfilm's Habitat: Part 1".

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Habitat (1987) Commodore 64 credits". MobyGames. Blue Flame Labs. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- ^ a b c Morningstar, C. and F. R. Farmer (1990) "The Lessons of Lucasfilm's Habitat", The First International Conference on Cyberspace, Austin, TX, USA

- ^ Robinett, W. (1994). "Interactivity and Individual Viewpoint in Shared Virtual Worlds: The Big Screen vs. Networked Personal Displays". Computer Graphics, 28(2), 127e

- ^ a b Robert Rossney (June 1996). "Metaworlds". Wired. Vol. 4, no. 6. Retrieved 2008-02-26.

- ^ Castronova, Edward (2006). Synthetic Worlds: The Business and Culture of Online Games. University Of Chicago Press. pp. 291. ISBN 0-226-09627-0.

... established Habitat as a result. This is described as a 2D graphical MUD ...

- ^ a b Lytel, David (Winter 1986). "Between Here and Interactivity". Hispanic Engineer & IT. 2 (5). Career Communications Group: 50–54. ISSN 1088-3452.

- ^ GameSpot, "Classic Studio Postmortem: Lucasfilm Games", Chip Morningstar, 24 March 2014, accessed 03 April 2015

- ^ "The Game Archeologist Moves Into Lucasfilm's Habitat". Joystiq. 2012-01-10. Archived from the original on 2013-08-10. Retrieved 2013-07-09.

- ^ Smith, Rob (2008). Rogue Leaders: The Story of LucasArts. Chronicle Books. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-8118-6184-7.

- ^ a b "Habitat Chronicles: You can't tell people anything".

- ^ "Habitat Chronicles: Elko I: The Life, Death, Life, Death, Life, Death, and Resurrection of the Elko Session Server".

- ^ "Resume -- Chip Morningstar".

- ^ Remembering 1.x, Lizard Man, November 3rd, 1998

- ^ Rossney

- ^ Stratagem Corporation Archived 2008-11-21 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "The Lessons of Lucasfilm's Habitat". stanford.edu. Retrieved 6 June 2016.

- ^ Wardrip-Fruin, Noah and Nick Montfort, eds. The New Media Reader. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2003. ISBN 0-262-23227-8. "Lucasfilm's Habitat" pp. 663–677.

- ^ "The Habitat Hackathon". The Museum of Art and Digital Entertainment. Archived from the original on 21 July 2016. Retrieved 6 June 2016.

- ^ "Bringing Habitat Back to Life". PasteMagazine. 3 February 2016. Retrieved 2016-02-22.

- ^ Francis, Bryant (2016-07-06). "Source code for Lucasfilm Games' '80s MMO Habitat released". Gamasutra. Retrieved 2016-07-06.

- ^ Lucasfilm Games' MMO 'Habitat' source code released by Brittany Vincent on Engadget.com (2016-07-07)

- ^ "NeoHabitat Website". GitHub.

- ^ a b c d e Ty Burr

- ^ Bruce Damer

- ^ a b c Steve Homer

- ^ Business Week

- ^ Voyage on the Argo: Joining the Dreamscape Community, Bruce Damer

- ^ a b Gullible's Travels: Through the Dreamscape, Bruce Damer, Avatars!, "This is not a shoot-em-up world"

- ^ "WorldsAway Fact Sheet". www.worldsaway.com. Archived from the original on 20 November 1996. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- ^ paleotronic (2018-07-01). "A 1980s Quantum Link to a modern-day Mutiny". Paleotronic Magazine. Retrieved 2021-08-20.

- ^ McCracken, Harry (2016-08-27). "Welcome To 1986: Inside "Halt And Catch Fire's" High-Tech Time Machine". Fast Company. Retrieved 2021-08-20.

- ^ Wagner, Roy (September–October 1986). "Habitat: A Lucasfilm Ltd and QuantumLink Production". Computer Gaming World. Vol. 1, no. 31. pp. 26–28, 44.

- ^ "Commodore MicroComputer Issue 44". Commodore Magazine. November 1986.

- ^ "RUN_Issue_032__1986_08__CW_Communications__300dpi_".

Bibliography

[edit]- ^ Bruce Damer (1997). "WorldsAway". digitalspace.com. Retrieved 2008-02-25.

Depth 2 1/2-D

- ^ Ty Burr (1996-05-03). "The Palace; Worldsaway; Worlds Chat". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on 2008-08-30. Retrieved 2008-02-25.

- ^ Steve Homer (1996-06-17). "Nothing on telly? There will be". The Independent. Archived from the original on 2013-07-09. Retrieved 2008-02-25.

Online chat system that allows users to adopt personalities through avatars, surrogate graphic characters which appear on screen. As people "talk" (by typing on their keyboards) words appear in speech bubbles.

- ^ Steven V. Brull; Robert D. Hof; Julia Flynn; Neil Gross (1996-03-18). "FUJITSU GETS WIRED (int'l edition)". Business Week. Archived from the original on 2013-01-18. Retrieved 2008-02-25.

More than 15,000 subscribers, intrigued by this extension of "chat", log on via CompuServe in 147 countries around the world.

- ^ Robert Rossney (June 1996). "Metaworlds". Wired. Vol. 4, no. 6. Retrieved 2008-02-26.

Literature

[edit]- Farmer, F. R. (1993). "Social Dimensions of Habitat's Citizenry". Virtual Realities: An Anthology of Industry and Culture, C. Loeffler, ed., Gijutsu Hyoron Sha, Tokyo, Japan

- "Habitat Anecdotes and other boastings" by F. Randall Farmer (Fall 1988), Electric Communities

External links

[edit]- Playing Catch Up: Habitat's Chip Morningstar and Randy Farmer Archived 2019-02-17 at the Wayback Machine on Gamasutra by Alistair Wallis (October 12, 2006)

- VZN's guide to Club Caribe, screenshots and comparisons to the modern version of Habitat, Vzones

- COMPUTE! magazine article about Habitat from COMPUTE! ISSUE 77 / OCTOBER 1986 / PAGE 32

- Enter The Online World of Lucasfilm RUN Magazine issue 32

- VZones website

- VZones Network Archives archives of locales, screenshots and info from 1995 to 2003

- WorldsAway Graphics archived screenshots from 1996

- Original WorldsAway DreamScape website

- 1986 video games

- Commercial video games with freely available source code

- Commodore 64 games

- CompuServe

- FM Towns games

- Internet Protocol based network software

- LucasArts games

- Classic Mac OS games

- Massively multiplayer online role-playing games

- Online chat

- Video games developed in the United States

- Windows games

- Graphical MUDs

- Virtual world communities