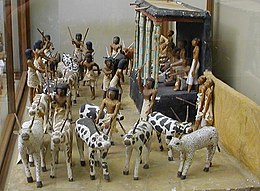

Wooden tomb model

Wooden tomb models were deposited as grave goods in the tombs and burial shafts throughout early Egyptian History, most notably in the Middle Kingdom of Egypt. They included a wide variety of wooden figurines and scenes, such as boats, granaries, baking and brewing scenes and butchery scenes. These served as ways to preserve the action depicted for eternity in honor of the dead.[1] The use of wood rather than other materials became popular in the first intermediate period.[2] Over time the models of boats in particular went from life size to much smaller scale though they remained numerous, some boats being less than a meter in length and fleets at times being larger than 50 models. The 11th dynasty appears to be when there is a shift from making these burial boats river worthy to making them stand nicely for funerary display.[3]

The number of models of scenes and boats increased as the periods changed and the types of figures in tombs shifted from people giving offering to scenes of daily life. This culminates in the Middle Kingdom where tombs could have over thirty scenes depicted, over fifty boats and only a dozen or so people giving offering. Compared to tombs in Giza that may have only twenty models with servants depicted.[4]

Predynastic, Early Dynastic and Old Kingdom

[edit]

Pottery and ivory models from the Predynastic and Early Dynastic periods are rare, but have been found to include similar items and scenes to the later models such as granaries.[6][7] Stone miniature containers were developed at this time and use for ritual purposes with an introduction of copper containers in the 6th Dynasty however, pottery remained popular. These types of jars would also go on to inspire wooden models of stone containers in the Middle Kingdom.[8]

During the Old Kingdom, limestone models of single figures taking part in a variety of daily life activities such as farming, food preparation, brewing, animal butchering, and entertainment were produced. Wooden boat models also had become popular and have been found in elite burials.[6][7][9] The funerary boats of the Old Kingdom were often life size or at times oversized, believed to be part of the funerary precession a mummy would take or an offering to the deceased.[3] Boats of the predynastic period were modeled after boats used in swamps, while the Old Kingdom brought the introduction of square shaped river boats.[10] The models are often buried outside of the tomb, in the serdab, or in statue niches within the tomb.[11] towards the end of the 5th Dynasty was when the first wooden models came into production, though often alongside stone pieces. These wooden models were smaller than those of later periods and less decorative in style.[12] An example of this type of model can be seen to the right. Following the reign of Pepi II, such models are increasingly found in elite burials and in greater numbers.[6]

First Intermediate Period and Middle Kingdom

[edit]The First Intermediate Period models usually consisted of two or more human figures attached to a base in a scene.[13] These scenes can depict a variety of tasks including food production, crafting and other modes of specialized work though boats remained popular through this period as well.[14] Boats of this period continued to diversify with the introduction of a new type of curved river boat, as well as boats that modeled ceremonial boats relating to solar worship and funerary practices.[10] Boats would often come in pairs representing the trips north and south that a body would take before reaching its final resting place.[15]

Most funerary models that survive today are from the Middle Kingdom, where not only the number of models increased but the variety of the models and what they depicted increased as well. These models could be found in many areas of the burial such as the tomb chapel, floor niches and shafts, or in the burial chamber, a good example of this variety can be seen in the tomb of Nakhti at Asyut.[11] Models found in the burial chamber were orientated to the cardinal directions and coffin, and could be found both on top of the coffin and on the floor beside it. Most of the models are three-dimensional representations of common scenes that are found on tomb chapel walls. For example, granaries are found depicted on southern walls of Old Kingdom tomb chambers and as well as on the foot ends of Middle Kingdom coffins.[16] Examples of the variety of models that can be found from these periods can be seen in the slideshow below.

Some of the best known are the twenty-four wooden models that come from the tomb of Meketre (TT280), which are now found in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo and Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City.[23] The largest collection of models were found in Tomb 10A of Djehutynakht and his wife, also called Djehutynakht, at Dayr al-Barshā by the 1915 the Harvard University-Boston Museum of Fine Arts excavation which included "some 58 model boats and nearly three dozen models of daily life."[24] These models are now at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts.[25]

Late Middle Kingdom and New Kingdom

[edit]

During the reign of Senusret III, the use of wooden models in tombs declines and are no longer found.[14] However, frequently included in discussions of Middle Kingdom models are several model boats that have been found in New Kingdom royal burials, most notably the burial of Tutankhamun.[26] Tutankhamun's flotilla included thirty-five boats.[26] Other notable New Kingdom models are the boats of Queen Aahotep at Dra Abu el-Naga which includes one made of gold with silver figures and another made entirely of silver.[27]

References

[edit]- ^ Biase-Dyson, Camilla Di (2022-12-21). "Building Ideas out of Wood. What Ancient Egyptian Funerary 'Models' Tell Us about Thought and Communication". Cambridge Archaeological Journal. 33 (3): 413–429. doi:10.1017/S0959774322000385. ISSN 0959-7743.

- ^ "Model of a funerary boat". Boston Museum of Fine Arts. Retrieved 2023-02-28.

- ^ a b Florek, Stan; Bleechmore, Heather; Jones, Jana; McGregor, Colin; Pogson, R. E.; Specht, Jim (2021-09-22). "Egyptian funerary boat model in the Australian Museum: dating and analysis". Records of the Australian Museum. 73 (2): 67–85. doi:10.3853/j.2201-4349.73.2021.1738. ISSN 0067-1975.

- ^ "Egypt: The Ancient Egyptians as Model Builders". www.touregypt.net. Retrieved 2023-03-01.

- ^ "Statue of man hoeing from tomb of Tjeteti | Old Kingdom". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2023-03-14.

- ^ a b c Tooley, Angela M. J. "Models." In The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press, 2001. ISBN 0195102347. OCLC 163459051.

- ^ a b Tooley, Angela M. J. (1995). Egyptian models and scenes. Princes Risborough: Shire. p. 16. ISBN 0-7478-0285-8. OCLC 33360271.

- ^ Bárta, Miroslav (2006). The Old Kingdom art and archaeology : proceedings of the conference held in Prague, May 31-June 4, 2004. Czech Institute of Egyptology, Faculty of Arts, Charles University in Prague. OCLC 704483073.

- ^ Taylor, John H. (2001). Death and the afterlife in ancient Egypt. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 99–107. ISBN 0-226-79163-7. OCLC 45195698.

- ^ a b Reisner, George Andrew; Egypt. Maslahat al-Athar (1913). Models of ships and boats. Institute of Fine Arts Library New York University. Le Caire : Impr. de l'Institut français d'archéologie orientale.

- ^ a b Tooley, Angela M. J. (1995). Egyptian models and scenes. Princes Risborough: Shire. pp. 13–14. ISBN 0-7478-0285-8. OCLC 33360271.

- ^ "Statue of man hoeing from tomb of Tjeteti | Old Kingdom". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2023-03-01.

- ^ Tooley, Angela M. J. "Models." In The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press, 2001. ISBN 0195102347. OCLC 163459051.

- ^ a b Grajetzki, Wolfram (2003). Burial Customs in Ancient Egypt : Life in Death for Rich and Poor. London. ISBN 0-7156-3217-5. OCLC 51738396.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "The secrets of Tomb 10A : Egypt 2000 BC | WorldCat.org". www.worldcat.org. Retrieved 2023-03-14.

- ^ Willems, Harco (1988). Chests of life : a study of the typology and conceptual development of Middle Kingdom standard class coffins. Leiden: Ex Oriente Lux. ISBN 90-72690-01-X. OCLC 20343577.

- ^ "Model of a procession of offering bearers | Middle Kingdom". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2023-03-13.

- ^ "Model Cattle stable from the tomb of Meketre | Middle Kingdom". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2023-03-13.

- ^ "Model of a Granary with Scribes | Middle Kingdom". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2023-03-13.

- ^ "Model Paddling Boat | Middle Kingdom". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2023-03-14.

- ^ "Model Sporting Boat | Middle Kingdom". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2023-03-14.

- ^ modèle, 2023-02-09, retrieved 2023-03-13

- ^ "Model Bakery and Brewery from the Tomb of Meketre". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved 2021-03-19.

- ^ "The Secrets of Tomb 10A". Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Retrieved 2021-03-19.

- ^ The secrets of Tomb 10A : Egypt 2000 BC. Rita E. Freed, Boston Museum of Fine Arts. Boston: MFA Publications. 2009. pp. 151–179. ISBN 978-0-87846-747-1. OCLC 449186077.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b Jones, Dilwyn (1990). Model boats from the tomb of Tutʻankhamūn. Oxford: Griffith Institute. ISBN 0-900416-49-1. OCLC 23582589.

- ^ Tooley, Angela M. J. (1995). Egyptian models and scenes. Princes Risborough: Shire. pp. 55–56. ISBN 0-7478-0285-8. OCLC 33360271.

Further reading

[edit]- Jones, Dilwyn (1990). Model boats from the tomb of Tutʻankhamūn. Oxford: Griffith Institute. ISBN 0-900416-49-1. OCLC 23582589.

- Reisner, George Andrew (1913). Models of ships and boats. Le Caire: l'Institut français d'archéologie orientale

- Tooley, Angela M. J. "Models." In The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press, 2001. ISBN 0195102347. OCLC 163459051.

- Tooley, Angela M. J. (1995). Egyptian models and scenes. Princes Risborough: Shire. ISBN 0-7478-0285-8.

- Digital Egypt - Wooden Models

- Examination of Wooden Tomb Models - Penn Museum