Ball Square station

Ball Square | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

An outbound train at Ball Square, December 2022 | |||||||||||||

| General information | |||||||||||||

| Location | Broadway at Boston Avenue Somerville, Massachusetts | ||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 42°23′59.94″N 71°6′39.97″W / 42.3999833°N 71.1111028°W | ||||||||||||

| Line(s) | Medford Branch | ||||||||||||

| Platforms | 1 island platform (Green Line) | ||||||||||||

| Tracks | 2 (Green Line) 2 (Lowell Line) | ||||||||||||

| Connections | |||||||||||||

| Construction | |||||||||||||

| Bicycle facilities | 50-space "Pedal and Park" bicycle cage | ||||||||||||

| Accessible | Yes | ||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||

| Opened | December 12, 2022 | ||||||||||||

| Passengers | |||||||||||||

| 2030 (projected) | 1,890 daily boardings[1]: 49 | ||||||||||||

| Services | |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

Ball Square station is a light rail station on the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA) Green Line located at Ball Square in Somerville and Medford, Massachusetts. The accessible station has a single island platform serving the two tracks of the Medford Branch. It opened on December 12, 2022, as part of the Green Line Extension (GLX), which added two northern branches to the Green Line, and is served by the E branch.

The location was previously served by railroad stations. The Boston and Lowell Railroad (B&L) opened Willow Bridge station at Cambridge Road (now Broadway) by 1850. It was renamed North Somerville around 1878, and a new station building was constructed in the 1880s. The station was served by the Boston and Maine Railroad, successor to the B&L, until 1958. Extensions to the Green Line were proposed throughout the 20th century, most with North Somerville as one of the intermediate stations. A Ball Square station near the former station site was officially chosen for the GLX in 2008. Cost increases triggered a wholesale reevaluation of the GLX project in 2015, and a scaled-down station design was released in 2016. A design and construction contract was issued in 2017. Construction of Magoun Square station began in early 2020 and was largely completed by late 2021.

Station design

[edit]

Ball Square station is located off Broadway near Boston Avenue at Ball Square on the border of Somerville and Medford. (Both entrances are in Somerville, but the platform is in Medford.) The Lowell Line runs roughly northwest–southeast through the station area, with the two-track Medford Branch of the Green Line on the south side of the Lowell Line tracks. The station has a single island platform, 225 feet (69 m) long and 22.5 feet (6.9 m) wide, between the Green Line tracks northwest of Broadway. A canopy covers the full length of the platform.[2]

The platform is 8 inches (200 mm) high for accessible boarding on current light rail vehicles (LRVs), and can be raised to 14 inches (360 mm) for future level boarding with Type 9 and Type 10 LRVs; it is also provisioned for future extension to 300-foot (91 m) length.[3]: 12.1-5 The tracks and platform are located level with Boston Avenue; the Broadway bridge arcs over the tracks.[2] The main entrance is from the Broadway bridge, with a small footbridge to a headhouse structure; stairs plus an elevator for accessibility connect the headhouse to the southeast end of the platform. A secondary accessible entrance from Boston Avenue also connects to the southeast end, with a grade crossing of the inbound Green Line track.[2]

A 50-space "Pedal and Park" bike cage is located along the entrance from Boston Avenue. The Ball Square Traction Power Substation is located next to the northwest end of the station along Boston Avenue. The remaining station frontage along Boston Avenue is reserved for future transit oriented development.[2] Public art at the station includes Tour Jeté Series by Christine Vaillancourt – colored geometric glass forms located on the elevator tower – as well as historic images and views of Vaillancourt's artwork on panels on the station signs.[4][5] MBTA bus routes 80 and 89 stop on Broadway just west of Boston Avenue.[6][2]

History

[edit]Railroad station

[edit]

The Boston and Lowell Railroad opened through Somerville and Medford in 1835, although local passenger stops were not added until several years later. Willow Bridge station was open by 1850 at Cambridge Road (now Broadway) on the border between the municipalities.[7][8] It was named for the willow trees that lined nearby Winter Brook.[9] The station was briefly renamed Cambridge Road in the early 1850s, but reverted to Willow Bridge by 1858.[10][11][12] The station became an unloading point for cattle bound for the Brighton Abattoir; the railroad built a cattle station in 1859.[13] The wooden bridge was replaced in 1868 with an iron bridge, which was in turn replaced in 1893.[14][15]

By 1874, the station was located on the west side of the tracks just north of Broadway.[16] It was renamed North Somerville around 1878.[17][18] The original station building was replaced with a small Queen Anne style station in the 1880s.[19] In 1887, the B&L was leased by the Boston and Maine Railroad (B&M) as its Southern Division.[10] A southbound freight train derailed at the station on June 25, 1916, blocking the line for over 24 hours and attracting 10,000 onlookers.[20][21]

Streetcars consolidated under the Boston Elevated Railway, then automobiles, cut sharply into local railroad traffic. All stops south of North Somerville were closed by the late 1940s. On April 18, 1958, the Public Utilities Commission approved a vast set of cuts to B&M commuter service, including the closure of North Somerville, Tufts College, and Medford Hillside stations.[22] The three stations were closed on May 18, 1958, amid the first of a series of cuts.[23][24] The station building, modified for other uses, remained standing until the 1990s.[25][19]

Green Line Extension

[edit]Previous plans

[edit]The Boston Elevated Railway (BERy) opened Lechmere station in 1922 as a terminal for streetcar service in the Tremont Street subway.[26] That year, with the downtown subway network and several radial lines in service, the BERy indicated plans to build three additional radial subways: one paralleling the Midland Branch through Dorchester, a second branching from the Boylston Street subway to run under Huntington Avenue, and a third extending from Lechmere Square northwest through Somerville.[27]

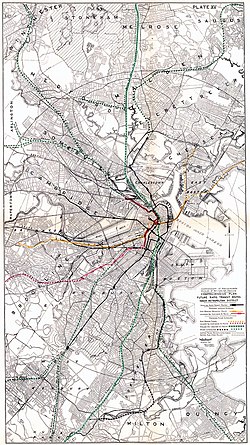

The Report on Improved Transportation Facilities, published by the Boston Division of Metropolitan Planning in 1926, proposed extension from Lechmere to North Cambridge via the Southern Division and the 1870-built cutoff. Consideration was also given to extension past North Cambridge over the Lexington Branch, and to a branch following the Southern Division from Somerville Junction to Woburn.[28][29]

In 1945, a preliminary report from the state Coolidge Commission recommended nine suburban rapid transit extensions – most similar to the 1926 plan – along existing railroad lines. These included an extension from Lechmere to Woburn over the Southern Division, rather than using the Fitchburg Cutoff. North Somerville was to be among the intermediate stations.[30]: 16 [31][32] The 1962 North Terminal Area Study recommended that the elevated Lechmere–North Station segment be abandoned. The Main Line (now the Orange Line) was to be relocated along the B&M Western Route; it would have a branch following the Southern Division to Arlington or Woburn.[33]

The Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA) was formed in 1964 as an expansion of the Metropolitan Transit Authority to subsidize suburban commuter rail service, as well as to construct rapid transit extensions to replace some commuter rail lines.[23]: 15 In 1965, as part of systemwide rebranding, the Tremont Street subway and its connecting lines became the Green Line.[34] The 1966 Program for Mass Transportation, the MBTA's first long-range plan, listed a short extension from Lechmere to Washington Street as an immediate priority, with a second phase reaching to Mystic Valley Parkway (Route 16) or West Medford.[35][28]

The 1972 final report of the Boston Transportation Planning Review listed a Green Line extension from Lechmere to Ball Square as a lower priority, as did several subsequent planning documents.[28][36] In 1980, the MBTA began a study of the "Green Line Northwest Corridor" (from Haymarket to Medford), with extension past Lechmere one of its three topic areas. Extensions to Tufts University or Union Square were considered.[37]: 308 [38]

Station planning

[edit]A 1991 agreement between the state and the Conservation Law Foundation, which settled a lawsuit over auto emissions from the Big Dig, committed to the construction of a "Green Line Extension To Ball Square/Tufts University".[39] No progress was made until an updated agreement was signed in 2005.[40] The Beyond Lechmere Northwest Corridor Study, a Major Investment Study/alternatives analysis, was published in 2005. The analysis studied a variety of light rail, bus rapid transit, and commuter rail extensions, most of which included a Ball Square station near the former North Somerville station site. The highest-rated alternatives all included an extension to West Medford with Ball Square as one of the intermediate stations.[41]

The Massachusetts Executive Office of Transportation and Public Works submitted an Expanded Environmental Notification Form (EENF) to the Massachusetts Executive Office of Environmental Affairs in October 2006. The EENF identified a Green Line extension with Medford and Union Square branches as the preferred alternative.[42] Planned station sites for the Green Line Extension (GLX) were announced in May 2008. Locations at both Broadway and Harvard Street were considered for Ball Square station. The Broadway site was chosen due to its proximity to Ball Square, more public support, and better station spacing.[43][44][45] An alternative with a tunnel from Ball Square to Alewife via Powderhouse Square and Clarendon Hill was analyzed later in 2008. It was found to be technically feasible but not cost-effective.[46]

The Draft Environmental Impact Report (DEIR), released in October 2009, concurred with the Broadway site, noting also the connections available to the route 80 and 89 buses.[47] Preliminary plans in the DEIR called for the station to have a single island platform northwest of Broadway. A two-level headhouse with stairs, two escalators, and four elevators would have entrances from a plaza on Boston Avenue and from the Broadway bridge.[1]: 49 [48] A Ball Square commuter rail station – either in addition to a Green Line station or in lieu of it – was listed as a possibility in 2012 as an interim air quality mitigation measure in response to delays in building the Green Line Extension. However, such a station would have been costly to build and could not have been completed by the 2015 deadline, and was thus not supported by MassDOT.[49]

Updated plans shown in June 2011 changed the headhouse exterior and modified the emergency exit from the northwest end of the platform.[50] Plans presented in February 2012 added a bike cage, a traction power substation, and a drop-off area for The Ride at the lower plaza.[51][52] By late 2012, the portion of the Medford Branch from Gilman Square station to College Avenue was expected to be completed by June 2019.[53] A further update in June 2013 moved the headhouse back 60 feet (18 m) from Broadway to avoid a buried NStar power distribution line that had not been previously known. The substation was set back from Boston Avenue to leave room for future transit oriented development, while part of the plaza became sloped terraces.[54][55] Design was then paused while Phase 2/2A stations (Lechmere, Union Square, and East Somerville) were prioritized, as they were scheduled to open sooner than the rest of the GLX. Design resumed in fall 2014 and reached 90% by May 2015.[56]

Redesign

[edit]In August 2015, the MBTA disclosed that project costs had increased substantially, triggering a wholesale re-evaluation of the GLX project.[57] In December 2015, the MBTA ended its contracts with four firms. Construction work in progress continued, but no new contracts were awarded.[58] At that time, cancellation of the project was considered possible, as were elimination of the Union Square Branch and other cost reduction measures.[59][60] In May 2016, the MassDOT and MBTA boards approved a modified project that had undergone value engineering to reduce its cost. Stations were simplified to resemble D branch surface stations rather than full rapid transit stations, with canopies, faregates, escalators, and some elevators removed. Ball Square station was reduced to a single entrance from Boston Avenue with an at-grade crossing of the inbound track; there would be no elevators and no access from the Broadway bridge.[61][62]

In December 2016, the MBTA announced a new planned opening date of 2021 for the extension.[63] A design-build contract for the GLX was awarded in November 2017.[64] The winning proposal included six additive options – elements removed during value engineering – including full-length canopies at all stations, as well as an entrance from the Broadway bridge with a single elevator and stairs.[65][66][67] Station design advanced from 0% in March 2018 to 45% that December and to 95% in October 2019.[68][2]

Construction

[edit]

The Broadway bridge adjacent to the station required replacement with a longer bridge to accommodate the Green Line tracks. A temporary utility bridge was constructed in the first half of 2015.[69] Replacement of the road bridge required a lengthy closure of Broadway — one of the primary east–west arterials in Somerville. Several options to shorten the detour for pedestrians, including retrofitting the utility bridge to serve as a footbridge, were found to be infeasible.[70] The bridge closed on March 22, 2019, with bus routes 80 and 89 detoured.[71][72] Demolition of the old bridge began the next day.[73] The new bridge partially opened (with one lane per direction and one sidewalk) on June 6, 2020, and was fully opened by November.[74][75][76]

Several older buildings, including a bowling alley, were demolished in April 2019 to make way for the station and the traction power substation.[77][78] Work on the substation was underway by February 2020.[79] Construction of the platform foundation began by August 2020; it was completed by November, with the platform poured by the end of the year.[80][81][82] The canopy was completed in April 2021, with the elevator shaft and headhouse frame erected in May.[83][84][85] In July 2021, the MBTA indicated that planning for adjacent transit-oriented development would not take place until after the station opened.[86]

Original plans called for the D branch to be extended to Medford/Tufts.[87][88] However, in April 2021, the MBTA indicated that the Medford branch would instead be served by the E branch.[89] By March 2021, the station was expected to open in December 2021.[90] In June 2021, the MBTA indicated an additional delay, under which the station was expected to open in May 2022.[91] In February 2022, the MBTA announced that the Medford Branch would open in "late summer".[92] Train testing on the Medford Branch began in May 2022.[93] In August 2022, the planned opening was delayed to November 2022.[94] The Medford Branch, including Ball Square station, opened on December 12, 2022.[95]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Chapter 3: Alternatives" (PDF). Green Line Extension Project Draft Environmental Impact Report / Environmental Assessment and Section 4(f) Statement. Massachusetts Executive Office of Transportation and Public Works; Federal Transit Administration. October 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 5, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f "Public meeting boards". Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. November 19, 2019. pp. 23–26.

- ^ "Execution Version: Volume 2: Technical Provisions" (PDF). MBTA Contract No. E22CN07: Green Line Extension Design Build Project. Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. December 11, 2017.

- ^ Gordon, Jane Keller (June 1, 2020). "New Somerville MBTA station will feature Boston painter's artwork in glass". Fifty Plus Advocate.

- ^ "GLX Community Working Group Monthly Meeting #39". Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. February 2, 2021. pp. 17, 18.

- ^ "2025 System Map". Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. December 15, 2024.

- ^ Pathfinder Railway Guide for the New England States. Snow & Wilder. December 1849. OCLC 476657834.

- ^ The Directory of the City of Boston. George Adams. 1850. p. 50 – via Google Books.

- ^ Mann, Moses Whitcher (1904). "West Medford in 1870". Medford Historical Society Papers. Vol. 8. Medford Historical Society.

- ^ a b Karr, Ronald Dale (2017). The Rail Lines of Southern New England (2 ed.). Branch Line Press. pp. 283, 286. ISBN 9780942147124.

- ^ Draper, Martin Jr. (1852). "Map of Somerville, Mass". J.T. Powers & Co.

- ^ ABC Pathfinder Railway Guide. New England Railway Publishing Company. June 1858. p. 18 – via Google Books.

- ^ Dennison, Edward B. (March 1936). "Medford Railroad Stations: Notes and Reminiscences". The Medford Historical Register. Vol. 39, no. 1 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Report of the Selectmen". Reports of the Town Officers of Somerville for the Year 1868. Somerville, Mass. 1869. p. 7.

- ^ "Somerville". Boston Post. February 1, 1893. p. 7 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Plate K". Atlas of the city of Somerville, Massachusetts : from actual surveys and official records. G.M. Hopkins & Co. 1874. pp. 44–45 – via Norman B. Leventhal Map Center.

- ^ ABC Pathfinder Railway Guide. New England Railway Publishing Company. August 1877. p. 56 – via Google Books.

- ^ ABC Pathfinder Railway Guide. New England Railway Publishing Company. July 1878. p. 60 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Fitch & Hollister; The Public Archaeology Laboratory (May 1990). "North Somerville Railroad Station" – via Massachusetts Cultural Resource Information System.

- ^ "Twenty-Five Cars Derailed". Boston Globe. June 25, 1916. p. 11 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "10,000 View Scene of Wreck". Boston Globe. June 26, 1916. p. 16 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Drastic Service Cuts Approved on Five B.& M. Divisions". Daily Boston Globe. April 19, 1958. p. 11 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Humphrey, Thomas J.; Clark, Norton D. (1985). Boston's Commuter Rail: The First 150 Years. Boston Street Railway Association. p. 57. ISBN 9780685412947.

- ^ "B.&M. Closes Saugus Branch, 3 Other Lines". Daily Boston Globe. May 17, 1958. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Rails of the Past Guiding the Green Line of the Future" (PDF). Somerville Bicycle Committee and the Somerville Historic Preservation Commission. May 31, 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 2, 2016.

- ^ "New Lechmere Sq Transfer Station, Open for L Traffic". Boston Globe. July 10, 1922. p. 9 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Three New Subways Planned". Boston Globe. June 25, 1922. p. 71 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c Central Transportation Planning Staff (November 15, 1993). "The Transportation Plan for the Boston Region - Volume 2". National Transportation Library. Archived from the original on May 5, 2001.

- ^ Report on Improved Transportation Facilities in Boston. Division of Metropolitan Planning. December 1926. pp. 6, 7, 34, 35. hdl:2027/mdp.39015049422689.

- ^ Clarke, Bradley H. (2003). Streetcar Lines of the Hub - The 1940s. Boston Street Railway Association. ISBN 0938315056.

- ^ Boston Elevated Railway; Massachusetts Department of Public Utilities (April 1945), Air View: Present Rapid Transit System – Boston Elevated Railway and Proposed Extensions of Rapid Transit into Suburban Boston – via Wikimedia Commons

- ^ Lyons, Louis M. (April 29, 1945). "El on Railroad Lines Unified Transit Plan". Boston Globe. pp. 1, 14 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Barton-Aschman Associates (August 1962). North Terminal Area Study. pp. iv, 51, 59–61 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Belcher, Jonathan. "Changes to Transit Service in the MBTA district" (PDF). Boston Street Railway Association.

- ^ A Comprehensive Development Program for Public Transportation in the Massachusetts Bay Area. Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. 1966. pp. V-20 – V-23 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Boston Transportation Planning Review Final Study Summary Report. Massachusetts Executive Office of Transportation and Construction. February 1973. pp. 15, 17 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ McCarthy, James D. "Boston's Light Rail Transit Prepares for the Next Hundred Years" (PDF). Special Report 221: Light Rail Transit: New System Successes at Affordable Prices. Transportation Research Board: 286–308. ISSN 0360-859X.

- ^ "Beyond Lechmere Northwest Corridor Project Project History" (PDF). Somerville Transportation Equity Partnership. June 3, 2004.

- ^ United States Environmental Protection Agency (October 4, 1994). "Approval and Promulgation of Air Quality Implementation Plans; Massachusetts—Amendment to Massachusetts' SIP (for Ozone and for Carbon Monoxide) for Transit Systems Improvements and High Occupancy Vehicle Facilities in the Metropolitan Boston Air Pollution Control District)". Federal Register. 59 FR 50498.

- ^ Daniel, Mac (May 19, 2005). "$770m transit plans announced". Boston Globe. pp. B1, B4 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Vanasse Hangen Brustlin, Inc (August 2005). "Chapter 4: Identification and Evaluation of Alternatives – Tier 1" (PDF). Beyond Lechmere Northwest Corridor Study: Major Investment Study/Alternatives Analysis. Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 5, 2016.

- ^ TranSystems (October 2006). "Green Line Extension Expanded Environmental Notification Form" (PDF). Massachusetts Executive Office of Transportation and Public Works. pp. 4–6. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 5, 2016.

- ^ Ryan, Andrew (May 7, 2008). "Potential Green Line stops announced in Somerville, Medford". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on May 10, 2008.

- ^ Vanasse Hangen Brustlin, Inc (May 1, 2008). "Green Line Extension Project" (PDF). Massachusetts Executive Office of Transportation and Public Works. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 5, 2016.

- ^ Vanasse Hangen Brustlin, Inc (May 2, 2008). "Green Line Extension Project: Summary of Station Evaluations/Site Selections" (PDF). Massachusetts Executive Office of Transportation and Public Works. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 5, 2016.

- ^ Vanasse Hangen Brustlin, Inc. Consideration of Tunnel Alignment Alternatives (PDF). Massachusetts Executive Office of Transportation & Public Works. pp. 8–14. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 28, 2017.

- ^ "Appendix B: Station and Alignment Selection Analysis" (PDF). Green Line Extension Project Draft Environmental Impact Report / Environmental Assessment and Section 4(f) Statement. Massachusetts Executive Office of Transportation and Public Works; Federal Transit Administration. October 2009. pp. 12–13. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 5, 2016.

- ^ "Chapter 3: Alternatives" (PDF). Green Line Extension Project Draft Environmental Impact Report / Environmental Assessment and Section 4(f) Statement. Massachusetts Executive Office of Transportation and Public Works; Federal Transit Administration. October 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 5, 2016. Figures 3.7-18, 3.7-19, 3.7-20, and 3.7-21.

- ^ Central Transportation Planning Staff (January 23, 2012). "Green Line Extension SIP Mitigation Inventory" (PDF). Massachusetts Department of Transportation. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 30, 2014.

- ^ ""Station Design Workshop": Ball Square Station" (PDF). Massachusetts Department of Transportation. June 9, 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 5, 2016.

- ^ "'Station Design Meeting': Ball Square and College Avenue Stations" (PDF). Massachusetts Department of Transportation. March 7, 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 5, 2016.

- ^ "Ball Square and College Avenue Station Design Meeting" (PDF). Massachusetts Department of Transportation. March 21, 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 5, 2016.

- ^ "Green Line Extension Project: Fall 2012 Fact Sheet" (PDF). Massachusetts Department of Transportation. November 5, 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 7, 2016. Retrieved February 9, 2018.

- ^ "Ball Square Station Design Meeting" (PDF). Massachusetts Department of Transportation. June 3, 2013. pp. 41–53. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 5, 2016.

- ^ "Public Meeting – Summary Minutes" (PDF). Massachusetts Department of Transportation. June 3, 2013. pp. 2–3. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 5, 2016.

- ^ "Ball Square & College Avenue Stations" (PDF). Massachusetts Department of Transportation. May 14, 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 5, 2016.

- ^ Metzger, Andy (August 24, 2015). "Ballooning Cost Throws Future Of Green Line Extension Into Question". WBUR.

- ^ Conway, Abby Elizabeth (December 10, 2015). "MBTA Ending Several Contracts Associated With Green Line Extension Project". WBUR.

- ^ Conway, Abby Elizabeth (December 9, 2015). "Axing Green Line Extension Still On The Table, Pollack Says". WBUR.

- ^ Arup (December 9, 2015). "Cost Reduction Opportunities" (PDF). Massachusetts Bay Transportation Agency.

- ^ Interim Project Management Team Report: Green Line Extension Project (PDF). MBTA Fiscal and Management Control Board and the MassDOT Board of Directors. May 9, 2016. pp. 5, 6, 10, 11, 45.

- ^ Dungca, Nicole (May 10, 2016). "State OK's a cut-down Green Line extension". Boston Globe. pp. A1, A9 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Dungca, Nicole (December 7, 2016). "New Green Line stations are delayed until 2021". Boston Globe. Archived from the original on December 9, 2016.

- ^ Vaccaro, Adam (November 20, 2017). "Green Line extension contract officially approved". Boston Globe. Archived from the original on January 24, 2018.

- ^ Jessen, Klark (November 17, 2017). "Green Line Extension Project Design-Build Team Firm Selected" (Press release). Massachusetts Department of Transportation. Archived from the original on January 28, 2022.

- ^ "GLX Program Update" (PDF). Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. November 20, 2017.

- ^ Response to the Request for Proposal for the Green Line Extension Design Build Project (PDF). GLX Constructors. September 2017. (Volume 2)

- ^ "GLX Project Open House". Massachusetts Department of Transportation. January 30, 2019. p. 14.

- ^ "GLX Bridge Work Jan. 19 - Ball Sq" (Press release). City of Somerville. January 15, 2015.

- ^ "GLX Community Working Group Monthly Meeting". Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. August 7, 2018. pp. 10–38.

- ^ "GLX Community Working Group Monthly Meeting". Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. March 5, 2019. p. 18.

- ^ "Somerville Bridge Closures" (Press release). Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. May 17, 2019.

- ^ "GLX Community Working Group Monthly Meeting". Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. April 2, 2019. p. 6.

- ^ "GLX Community Working Group Monthly Meeting #44". Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. July 6, 2021. p. 24.

- ^ "GLX Community Working Group Monthly Meeting #36". Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. November 3, 2020. p. 26.

- ^ "Green Line Extension to Reopen Two Major Bridges in Somerville" (Press release). Massachusetts Department of Transportation. May 28, 2020. Archived from the original on March 28, 2022. Retrieved June 14, 2022.

- ^ "GLX Community Working Group Monthly Meeting". Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. April 2, 2019. p. 18.

- ^ "GLX Community Working Group Monthly Meeting". Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. May 7, 2019. p. 16.

- ^ "GLX Community Working Group: Monthly Meeting". Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. February 4, 2020. p. 30.

- ^ "GLX Community Working Group Monthly Meeting: August 4, 2020". Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. August 4, 2020. p. 10.

- ^ "GLX Community Working Group: Monthly Meeting #36". Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. November 3, 2020. p. 20.

- ^ "Community Working Group (CWG) Meeting Minutes". Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. January 5, 2021. p. 3.

- ^ "GLX Community Working Group Monthly Meeting #41". Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. April 6, 2021. p. 22.

- ^ "GLX Community Working Group Monthly Meeting #42". Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. May 4, 2021. p. 30.

- ^ "Ball Square Station elevator shaft and headhouse to provide station access from Broadway Bridge. 20210608-IMG_0894". GLX Constructors. June 8, 2021 – via Flickr.

- ^ State House News Service (July 6, 2021). "MBTA hits pause on Green Line development talks". Boston Herald. Retrieved June 14, 2022.

- ^ "MBTA Light Rail Transit System OPERATIONS AND MAINTENANCE PLAN" (PDF). Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. January 6, 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 7, 2017.

- ^ "Travel Forecasts: Systemwide Stats and SUMMIT Results" (PDF). Green Line Extension Project: FY 2012 New Starts Submittal. Massachusetts Department of Transportation. January 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 7, 2017.

- ^ DeCosta-Klipa, Nik (April 9, 2021). "The MBTA is planning to open part of the Green Line Extension this October". Boston Globe. Retrieved April 9, 2021.

- ^ "Report from the General Manager" (PDF). Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. March 29, 2021. p. 20.

- ^ Dalton, John (June 21, 2021). "Green Line Extension Update" (PDF). Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. p. 19.

- ^ Lisinski, Chris (February 24, 2022). "Green Line Extension service to begin March 21". WBUR. Retrieved February 25, 2022.

- ^ "Train Testing Begins on New Green Line Medford Branch" (Press release). Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. July 5, 2022.

- ^ "Building A Better T: GLX Medford Branch to Open in Late November 2022; Shuttle Buses to Replace Green Line Service for Four Weeks between Government Center and Union Square beginning August 22" (Press release). Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. August 5, 2022.

- ^ "MBTA Celebrates Opening of the Green Line Extension Medford Branch" (Press release). Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. December 12, 2022.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Ball Square station at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Ball Square station at Wikimedia Commons