William Henry Powell (soldier)

William Henry Powell | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | May 10, 1825 Pontypool, Torfaen, Wales, U.K. |

| Died | December 26, 1904 (aged 79) Belleville, Illinois, U.S. |

| Buried | Graceland Cemetery, Chicago, Illinois, U.S. |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1861–1865 |

| Rank | |

| Commands | 2nd W.V. Cavalry Regiment Brigade, Army of West Virginia Division, Army of West Virginia |

| Battles / wars | American Civil War |

| Awards | |

William Henry Powell (May 10, 1825 – December 26, 1904) was an American soldier who fought for the Union in the American Civil War. He was a leader in the iron and nail business before the war, and his leadership abilities proved useful in the military. Powell began as a captain, and quickly ascended to higher roles in the cavalry, including commanding a regiment, a brigade, and then a division. Powell was awarded his country's highest award for bravery during combat, the Medal of Honor, for heroism at Sinking Creek, Virginia, when, as leader of a group of 22 men, he captured an enemy camp and took over 100 prisoners. This was accomplished without the loss of any of his men on November 26, 1862. He was honored with the award on July 22, 1890.

In July 1863, Powell was shot while leading cavalry in Wytheville, Virginia. Although surgeons on both sides of the conflict believed his wound was fatal, Powell survived—and became a prisoner of war. He was later exchanged, and returned to his command of the 2nd West Virginia Volunteer Cavalry Regiment. In 1864, Powell commanded brigades while fighting mostly in the Shenandoah Valley under the direct supervision of General William W. Averell in an army commanded by General Philip Sheridan. Eventually, Powell replaced Averell as division commander. Powell led cavalry in numerous battles, including Moorefield, Opequon, and Fisher's Hill. He resigned as a brigadier general in January 1865 to tend to family health issues. He was later brevetted to major general. Powell returned to his original profession working in the iron making industry, and was active in the Grand Army of the Republic, a fraternal organization of Union veterans of the American Civil War.

In a letter sent to headquarters in 1864, General George Crook said "Colonel Powell has served with me often since the commencement of the war. He has distinguished himself in every battle he was engaged in under me. He has been recommended by me on several occasions, for promotion. I regard him as one of the best cavalry officers I have ever seen in the service."

Early life

[edit]William Henry Powell was born on May 10, 1825, in Pontypool, South Wales.[1] At the time, the community was part of Monmouthshire, an iron-making region. Both of his parents, William and Sarah Griffith Powell, were Welsh.[2][3] His father immigrated to the United States in 1827, and his mother followed in 1830 with the rest of the family. Originally, they lived in New Jersey and Pennsylvania, but they moved to Nashville, Tennessee, in 1833. Powell's father was an ironworker, and was employed by the Gennessee Iron Works. Powell began to learn his father's profession while still a boy, working in a rolling mill and nail factory in Nashville.[4] In 1840, the Gennessee Iron Works closed because of a recession. The family moved north to Wheeling, Virginia, in 1843. Powell's father began employment at Wheeling's Rolling Mill Nail Factory.[3]

Powell continued learning his father's profession in Wheeling. Four years after the move to Wheeling, he built the Benwood Nail Works while only 22 years old, and became its superintendent.[4] In 1846, he was involved in an accident at the nail iron works and lost vision of his right eye. Powell married Sarah Gilchrist in 1847, and they eventually had six children. Two children died in infancy, and one died at age 20.[3] In 1853, the family moved to Ironton, Ohio, which is located southwest of Wheeling along the Ohio River. In Ironton, Powell built the Bellfonte Nail Works.[5] When the American Civil War began in 1861, Powell was general superintendent and financial agent of this large iron works.[6] He left the business in August to begin service as a cavalry captain.[5]

American Civil War: Western Virginia

[edit]Between September 20, 1860, and February 1, 1861, seven southern states seceded from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America.[Note 1] Fighting began on April 12, 1861, when American troops were attacked at Fort Sumpter in South Carolina. This is considered the beginning of the American Civil War. Four additional states, including Virginia, seceded during the next three months.[10] Some of the northwestern counties of Virginia disagreed with secession and they met in Wheeling to form a Restored Government of Virginia loyal to the United States.[11]

Initially, the "War of the Rebellion" was not expected to last long.[12] However, the war continued through the summer, and President Abraham Lincoln called for volunteers to fight against the rebels of the Confederacy. Powell resigned his civilian job on August 1, 1861, and recruited enough men to form a company of cavalry and was elected their captain.[2] Ten companies were united to form a cavalry regiment which consisted mostly of men from the Ohio counties located close to the Ohio River. The regiment was originally intended to be the 4th Ohio Cavalry,[13] but Ohio governor William Dennison refused to accept the unit's application because he had been instructed to accept no more new cavalry.[14] The regiment's application was accepted by the provisional governor of the Restored Government of Virginia, Francis Harrison Pierpont, and became the 2nd Regiment of Loyal Virginia Volunteer Cavalry.[14] Powell's company was designated Company B, and he was commissioned as its captain on August 14.[15] The regiment's first significant action was on January 7, 1862, in Louisa, Kentucky, where it assisted a force commanded by Colonel James A. Garfield, future President of the United States. Powell led his company, reinforced with men from the regiment's Company C, in a charge that drove back a Confederate rearguard.[16]

Kanawha Valley

[edit]

During 1862–1863, the 2nd Loyal Virginia Cavalry spent much of its time confronting bushwhackers—who were despised. The bushwhacker was thought of as an "unprincipled scoundrel who was too cowardly to join the army and fight as a man…", who would "sneak around like a thief in the night…."[17] Eventually, Union forces in the mountains of what became West Virginia became very ruthless in their treatment of bushwhackers.[18]

Powell was usually stationed near the Kanawha River Valley, in the southwestern portion of present West Virginia—which was part of Virginia at the time. Entire regiments were not needed for bushwhacker duty, so the regiment often worked in detachments of two companies. In April 1862, Powell's regiment was divided into two battalions.[19] Powell's battalion, commanded by Colonel William M. Bolles, joined some Ohio infantry regiments to form the 3rd Brigade of General Jacob Dolson Cox's Kanawha Division. The brigade was commanded by Colonel (later Major General) George Crook, a professional soldier with fighting experience in the American West. Crook's brigade normally operated independently from the other portion of Cox's division.[20] Its camp was located at Meadow Bluff, west of Lewisburg in Greenbrier County.[21]

Powell's major fighting experience as part of this brigade happened on May 27, against Confederate General Henry Heth. Crook's brigade ambushed Heth's force in Lewisburg, killing or wounding over 150 enemy soldiers and capturing over 150. The cavalry pursued the fleeing rebels and stopped only when a bridge was destroyed.[21] Shortly after this engagement, Colonel Bolles resigned and several officers of the 2nd Loyal Virginia Cavalry were promoted.[22] On June 25, 1862, Powell was promoted to major because of his gallant conduct in Kentucky and to fill a vacancy caused by the Bolles resignation.[23]

Kanawha Valley Campaign

[edit]During August 1862, many of the Union soldiers stationed in western Virginia were sent to Washington to reinforce the Army of Virginia. This caused the two battalions from the 2nd Loyal Virginia Cavalry to be reunited, and it was stationed with two infantry regiments in Kanawha Falls, close to Gauley Bridge, in what is now south central West Virginia. The small force was commanded by Colonel Joseph Andrew Jackson Lightburn.[24]

In September, the Confederate Army became aware of the Union Army's lack of manpower, and devised a plan of attack.[25] The Confederates sent a large force led by General William W. Loring, incorrectly rumored to be 10,000 men, to attack Lightburn from the southeast. A cavalry brigade of about 550 men led by Colonel Albert G. Jenkins patrolled along the Ohio River with the intention of preventing a retreat by Lightburn.[26] A large portion of the 2nd Loyal Virginia Cavalry, commanded by Colonel John C. Paxton, was sent to confront Jenkins. Powell led the advance guard, which happened to be Powell's company (Company B) before his promotion to major.[24] On September 8, Powell's advance group led the attack on Jenkins' rebel camp outside of Barboursville, which is close to the Ohio River. The camp was captured, and Jenkins barely escaped. The rebel force, which was much larger than Paxton's cavalry, was driven southward up the Guyandotte River.[27]

Thus, Powell's advance guard for Paxton enabled a safe retreat to the Ohio River for the remaining portion of Lightburn's small force.[27] Lightburn's report said "The Second Virginia Cavalry, under Colonel Paxton, did good service in keeping Jenkins' force at bay, thereby preventing an attack in our rear. I wish, also, to state that Colonel Paxton, with 300 men, attacked Jenkins' whole force (from 1,200 to 1,500), and drove them from Barboursville, which, no doubt, kept them from an attempt to harass our retreat."[28]

Sinking Creek raid

[edit]

Confederate gains in the Kanawha Valley did not last long, and Union troops reoccupied much of the valley. In November 1862, the 2nd Loyal Virginia Cavalry camped for the winter along the Kanawha River, about 12 miles (19 km) upriver from Charleston. Newly promoted Brigadier General George Crook commanded Union troops in the valley, and Paxton commanded Powell's regiment, the 2nd Loyal Virginia Cavalry. Crook was an experienced Indian fighter, and believed that adverse weather was an advantage in the hit-and-run fighting style of raids. On November 23, he ordered Paxton to rendezvous with an infantry regiment on Cold Knob Mountain, and then lead an attack on two rebel camps in Sinking Creek Valley.[29] Before the cavalry regiment departed, Crook confidentially told Powell to not return without good results.[30]

The cavalry reached their meeting place near the top of Cold Knob Mountain on November 26. The 11th Ohio Infantry had arrived a few hours earlier. The men from the infantry had marched through rain, and were caught (as was the cavalry) in a snowstorm.[31] After a conference between Paxton and the infantry's Colonel Philander P. Lane, the infantry aborted their mission and began a return to camp.[32] Paxton also considered aborting the mission, but was persuaded by Powell to continue. Paxton sent Powell and 2nd Lieutenant Jeremiah Davidson with 20 men from Company G down the mountain to scout for the rebel camps.[33]

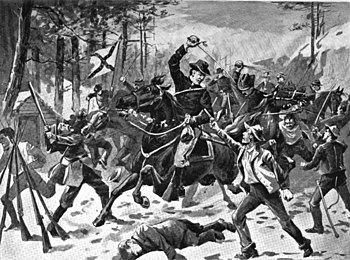

Powell and his men found one of the camps, determined that it was poorly guarded, and decided to capture it themselves. Each member of Powell's advance guard was armed with a saber and two six-shot revolvers. Powell decided to attack with sabers so that the other rebel camp would not be alarmed. They charged into the 500-man rebel camp with sabers drawn, and completely surprised the rebels. Many of the weapons captured were not loaded. Although hundreds of the rebels scattered into the countryside, a captain, a lieutenant and 112 enlisted men were captured, along with 200 weapons, a few wagons and some camping equipment. Powell's only casualties were the loss of two horses. Two rebels were killed and two wounded.[34] The trip back to camp was difficult because of the cold weather, and two men were hospitalized at the infantry's Summerville camp because of frostbite. Ten horses were lost because of cold and exhaustion. Paxton ended his report by writing "I cannot close this report without deservedly complimenting the officers and men, but, where all behaved so gallantly, it is impossible to particularize. But all honor is due Major Powell, who led the charge...."[35] Powell and Davidson were promoted shortly afterwards—Powell from major to lieutenant colonel, and Davidson from second lieutenant to first lieutenant.[36] After the war, Powell was awarded the Medal of Honor for his performance in the Sinking Creek raid.[Note 2] In 1889, Crook said that he regarded the "expedition as one of the most daring, brilliant and successful of the whole war."[43]

Regiment commander

[edit]During March 1863, Powell became severely ill, and was unable to recover at camp. He eventually resigned from the cavalry, and returned to his home in Ohio.[44] Powell was also unhappy with Paxton, although this was revealed to only a few.[Note 3] On May 1, Paxton led a night raid (without Powell) near Lewisburg, and the regiment was defeated with significant casualties. Total losses were sixteen killed, missing, or wounded—plus 28 horses killed. General Eliakim P. Scammon, the division commander after Crook had been sent elsewhere, dismissed Paxton after the regiment returned to camp. Paxton was popular with his troops, but the troops also respected Powell.[46] At the time of Paxton's dismissal, Powell's resignation had yet to be accepted, and he was still at home in Ohio regaining his health. After a petition by the regiment, Powell was persuaded to retract his resignation. He was promoted to colonel and became the regiment's commander effective May 13, 1863.[47]

Wytheville raid

[edit]

The Wytheville raid occurred on July 18, 1863, in southwestern Virginia. Powell was second in command of a small 800-man brigade of cavalry and mounted infantry.[48] He had some disagreements with how his commander, an infantry veteran named Colonel John Toland, handled the cavalry, and both men were shot early in the raid; Toland being killed on a street in Wytheville, and Powell believed to be mortally wounded.[Note 4] Although the Union brigade was able to secure the town, it suffered numerous casualties—and left town less than 24 hours after its arrival. Powell's wound was painful enough that he could not be moved, and he became a prisoner of the Confederates.[52]

The citizens of Wytheville blamed Powell for the burning of several homes and buildings, although the damage occurred after he was wounded.[53] When it appeared he might be harmed, a few of the local women intervened by hiding him in a hotel.[54] Powell unexpectedly recovered enough that he could be moved, and was eventually sent to Richmond's Libby Prison. He was placed in solitary confinement on charges of robbery and murder.[49] One of the men from the 2nd West Virginia cavalry wrote that "It was well known that the confederate authorities had placed Colonel Powell in a dungeon for some imaginary wrong...."[55] One of the main causes for his predicament was the burning of a house and barn near Lewisburg, West Virginia, an act that the Confederate army and Lewisburg community considered unjustified and without military purpose.[55]

On January 29, 1864, Powell was paroled for 30 days to negotiate his exchange for Confederate Colonel Richard H. Lee.[43] This negotiation was successful (Lee was a distant relative of Confederate General Robert E. Lee), and Powell returned to Ironton, Ohio, to continue his recuperation. On February 22, friends presented him with a gold watch, money to purchase a horse, a saber, and "a brace of Colt's ivory mounted 44 calibre navy revolvers."[Note 5] On March 20, 1864, he returned to Charleston and resumed command of the 2nd West Virginia Cavalry regiment.[58]

Cove Mountain

[edit]Around the time of Powell's return, Crook was assigned command of the entire Kanawha Division. In April, General William W. Averell arrived in Charleston with two regiments of cavalry.[59] On April 30, Crook organized a two prong attack against strategic Confederate locations along the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad. Crook led infantry from Charleston toward the Confederate regional headquarters at the Dublin Depot in Virginia. He sent cavalry under the command of Averell to attack Saltville, Virginia. Averell found Saltville strongly defended, so he decided to attack Wytheville instead. To get to Wytheville, Averell needed to move the cavalry through the mountains at Cove Gap (also known as Grassy Lick) in northern Wythe County.[60]

On May 10, Averell's path through the gap was blocked by a large force commanded by Confederate General William E. "Grumble" Jones reinforced by cavalry led by General John Hunt Morgan. Originally, Averell's plan was to have Powell lead a cavalry charge into the gap with sabers drawn. However, the charge was cancelled after a reconnaissance mission discovered a mass of Confederate soldiers waiting to ambush the Union cavalry. Instead, the Union cavalry formed a battle line that drew the Confederates out of the gap. A four-hour battle ensued. Averell's forehead was grazed by a bullet, and he temporarily relinquished command.[60] The second in command, General Alfred N. Duffié, had a "conspicuous absence", so command fell to Powell.[Note 6] Powell was unable to get the cavalry through the gap, but he was able to make effective use of the 2nd West Virginia Cavalry, and hold off the larger Confederate force. The result of the battle was an inconclusive standoff that ended at dusk.[63]

During the night, a local slave led Averell's force on a difficult alternative route (Crab Orchard) through the mountains, and they eventually linked with Crook.[Note 7] Averell's report said "The General commanding desires to express his high appreciation of the skillful evolution of the 2nd Regiment, West Virginia Cavalry, under Colonel Powell, upon the field of battle. It was a dress parade that continued without disorder under a heavy fire for four hours."[61]

Hunter's Lynchburg Campaign

[edit]On June 9, an army commanded by General David Hunter was reorganized, and Powell was assigned command of the 3rd Brigade under Averell's 2nd Cavalry Division of the Army of West Virginia. This brigade consisted of the 1st West Virginia Cavalry and the 2nd West Virginia Cavalry.[Note 8] On June 10, Hunter's Lynchburg Campaign was organized, and troops departed from Stanton, Virginia, toward Lynchburg. Powell's brigade often took the advance for the main portion of Hunter's force, moving south to Lexington, then southeast toward Lynchburg.[67] Powell's cavalry approached Lynchburg from Campbell Courthouse, and pushed cavalries led by General John McCausland and General John D. Imboden to within four miles of Lynchburg during the morning of June 17.[69] Fighting continued periodically all day, and stopped at dusk. During this time, additional rebel troops were arriving in Lynchburg via the railroad.[70] Powell's brigade was sent out during the evening, and got close enough to the city that "the church spires of the city could be plainly seen."[71] Later during that morning, Powell was surprised to find out that the Union army (which had an ammunition shortage) was in full retreat, leaving his brigade in a dangerous situation. The brigade caught up with the rest of the retreating army near New London—just when the pursuing Confederates caught up with them. Averell's entire division, including Powell's brigade, became the rear guard as Hunter's army retreated west toward Charleston.[71]

American Civil War: Shenandoah Valley

[edit]After the retreat from Lynchburg to Charleston, the Army of West Virginia rested and resupplied. During July, it was transferred to the Shenandoah Valley. Powell commanded three West Virginia cavalry regiments as the 2nd Brigade of Averell's 2nd Cavalry Division. His brigade left Charleston on July 8, and arrived at a Baltimore & Ohio Railroad station in Parkersburg, West Virginia, on July 12. A few days later the brigade began its train ride to Martinsburg, West Virginia. Portions of the brigade arrived in Martinsburg on July 19, but the entire brigade did not arrive until around July 23.[72]

Rutherford's Farm and Kernstown II

[edit]

The Battle of Rutherford's Farm occurred on July 20. General Averell's force of infantry and cavalry defeated a larger force commanded by General Stephen Dodson Ramseur.[73] The battle took place on some farmland north of Winchester, Virginia, and is sometimes called the Battle of Carter's Farm. In this battle, two regiments from Powell's brigade (2nd West Virginia Cavalry and 3rd West Virginia Cavalry) caused the rebels to be "thrown into confusion" and "driven from the woods".[74]

A few days later (July 24), the Second Battle of Kernstown was fought. In this Confederate victory, Crook's Army of West Virginia was driven north by General Jubal Early's Army of the Valley. The Union retreat started south of Winchester and ended in the rain on the north side of the Potomac River.[75] The disorganized retreat featured panicking soldiers, burning Union supply wagons, and one cavalry commander becoming separated from his brigade.[Note 9] By the next day, Powell's brigade was the only cavalry unit still organized, and an infantry brigade commanded by (future President) Colonel Rutherford B. Hayes was among only two that remained organized.[78] Both units were instrumental in enabling the Union force to escape from pursuing rebel cavalry.[79]

Moorefield

[edit]Powell's brigade participated in one of Averell's most impressive victories on August 6, when it charged across the South Branch of the Potomac River, attacked McCausland's cavalry and recovered a portion of private property taken on July 30 from the residents of Chambersburg, Pennsylvania.[80] The attack drove McCausland's brigade "to the mountains, with the loss of his remaining artillery and many prisoners."[81] This battle ruined Early's Confederate cavalry in the Shenandoah Valley, and it was never again the dominant force it once was.[82]

Opequon and Fisher's Hill

[edit]The Third Battle of Winchester, also known as Opequon, occurred on September 19.[83] By this time, Major General Philip Sheridan had been assigned command of Union armies in the Shenandoah Valley.[84] This battle was a major victory for Sheridan, and it resulted in numerous casualties for both sides—including generals and colonels.[85] Powell remained in command of the 2nd Cavalry Brigade of Averell's 2nd Cavalry Division, which consisted of the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd West Virginia Cavalry Regiments. The brigade captured 80 prisoners and two pieces of artillery in a charge on the Winchester Heights.[86]

The Battle of Fisher's Hill occurred on September 21 and 22.[87] Sheridan wrote that the battle was "in a measure, a part of the battle of Opequon".[88] Following the fighting at Winchester, Powell's brigade led the pursuit of Early's army. On July 22, they fought dismounted because of the nature of the terrain.[89] After infantry commanded by Crook created a gap in the Confederate line, Powell's brigade (remounted) pushed through and pursued the fleeing Confederates. The pursuit was successful, and "[m]any prisoners were taken in this chase".[89]

Division commander

[edit]

In early September, several of Powell's superiors recommended him for promotion. Averell wrote that Powell "is a gentleman of high character, and one of the best brigade commanders that I know."[90] In a letter sent to headquarters in 1864, Crook said "Colonel Powell has served with me often since the commencement of the war. He has distinguished himself in every battle he was engaged in under me. He has been recommended by me on several occasions, for promotion. I regard him as one of the best cavalry officers I have ever seen in the service."[91] Sheridan also recommended Powell for promotion. President Lincoln wrote that Powell should at least be given a "brevet appointment, if a full commission is impracticable".[92]

Following the Battle of Fisher's Hill, the Union army continued pursuing Early's Army as it retreated south. At this time, Sheridan became dissatisfied with the pace of Averell's pursuit, and dismissed him as commander of the 2nd Cavalry Division. Powell was assigned command of the division on September 23.[89] Powell's command consisted of two brigades and a four-gun battery. The division's manpower when Powell became commander was 101 commissioned officers and 2,186 enlisted men present. Present and absent men totaled to 276 commissioned officers and 6,950 enlisted men.[Note 10] Because all but one person from Averell's staff left with Averell, and took the division's records, Powell had difficulty with the administrative work required of division commanders. He did not submit his first written report as division commander until October 27.[93]

On September 24, shortly after assuming command of the division, Powell moved his division from the Valley Pike to a road that leads to Harrisonburg. His advance guard skirmished with some rebel pickets, and it was discovered he was nearing cavalries commanded by Generals Imboden, Bradley Johnson, and McCausland. A major battle did not ensue, but Powell captured 18 prisoners, 14 wagons, and a large quantity of ammunition. Fifteen rebels were killed.[94] The skirmish occurred at Forest Hill, and was the first of two that would happen over the next few days.[95]

Powell's division reached Harrisonburg on September 25. For the next week, the division would spend its time patrolling a region bounded mostly by Harrisonburg, Brown's Gap, and Stanton. On September 27, Powell was ordered to cross the South River.[Note 11] His division crossed while leaving one regiment behind to guard their camp and wagons. After the river crossing, the guarding regiment was attacked by Fitzhugh Lee's cavalry supported by infantry. Powell re–crossed the river, changed fronts, and eventually drove back the attackers.[94] The main portion of this skirmish occurred at Weyer's Cave.[95] Powell guarded his left flank by slowly falling back toward the community of Port Republic while additional Confederate forces joined Lee and pursued. Powell crossed the North River and moved to Cross Keys where he met with General George Armstrong Custer. At that time, Custer assumed command of the 2nd Cavalry Division.[94]

General Ulysses S. Grant, commander of all Union forces, had two major goals in the Shenandoah Valley: eliminate Early's army and make the Valley unable to support any Confederate armies. With Early almost eliminated, the Union Army began to focus on the second goal. Troops were sent to destroy or consume livestock, crops, and forage. Structures such as barns, mills and tanneries were destroyed. This destruction of the fertile Shenandoah Valley became known as "The Burning".[96] On September 29, Custer moved the 2nd Cavalry Division from Cross Keys to Mount Sidney, where the division collected local horses and livestock, and destroyed forage, grain, and flour mills. The division moved to Mount Crawford, following the same orders to make the land unable to support the Confederate Army. On September 30, Custer was assigned to command the 3rd Cavalry Division, and Powell was again assigned to command the 2nd. Powell and his division reported to Major General Alfred T. Torbert at Harrisonburg on September 30.[97]

Luray Valley

[edit]On October 1, Powell moved the division north to Luray (as ordered by Torbert), "driving off all stock of every description, destroying all grain, burning mills, blast furnaces, distilleries, tanneries, and all forage".[97] While camped in Luray until the morning of October 7, Powell sent smaller groups on scouting expeditions and to hunt bushwhackers. On October 6, Powell destroyed a tannery used by the rebel army. The unfinished leather was said to be worth $800,000 (over $12 million in 2016 dollars).[97]

The division moved north from Luray to Front Royal on October 7, and then departed for Sperryville October 11—passing through Chester Gap to get there. This is where Powell began to face challenges from Confederate Colonel John S. Mosby's "guerrillas".[97] On October 13, Powell learned that one of his soldiers had been the victim of a "cold-blooded murder" by two members of Mosby's gang.[98] In retaliation, Powell hanged one of his prisoners that was part of Mosby's command. He left a sign on the hanged man that said "A.C. Willis, member of Company C, Mosby's command, hanged by the neck in retaliation for the murder of a U.S. Soldier by Messrs. Chancellor and Myers".[98] In addition, Powell had Chancellor's house, barn, and livestock destroyed.[98]

Battle of Cedar Creek

[edit]

On October 19, 1864, Powell was promoted to brigadier general.[68] On the same day, the Battle of Cedar Creek took place southwest of Middletown, Virginia.[99] The battle began in the morning with a Confederate attack. At that time, Powell's 1st Brigade was eight miles away from Powell and the 2nd Brigade, and closer to Cedar Creek.[100] When the battle started, this brigade was needed to support the Union Army's left, so it was detached to General Wesley Merritt.[101] Powell positioned the 2nd Brigade on the road to Front Royal, and prevented the Confederate cavalry under General Lunsford L. Lomax from flanking the main Union force.[102] A week later, the division skirmished with Lomax's Division further northwest at Middletown.[95]

Nineveh

[edit]On November 12, Powell again fought Lomax's Cavalry.[95] Elsewhere, Custer and Merritt attacked General Thomas L. Rosser's cavalry, and drove it back rapidly enough that Lomax was called for reinforcement.[103] This left a smaller force (still larger than a brigade) commanded by McCausland to face Powell. Powell sent most of his 1st Brigade out beyond Front Royal, where it encountered McCausland's force. The Confederates slowly pushed the 1st Brigade back. Powell brought his 2nd Brigade to the front, and the 1st Brigade moved to the rear.[104] The 2nd Brigade charged, resulting in a short clash that ended with the Confederates retreating as fast as they could. They were chased for eight miles.[105] Powell captured all of the rebel artillery (two guns), their ammunition train, and took 180 prisoners.[106] A newspaper account said that "Gen. Powell was on the field in person, and superintended the formation of the line of battle...."[107] The newspaper also added that 40 Confederates were killed or wounded. Among those killed were a colonel and two majors, and among those wounded (slightly) was McCausland—"the scoundrel who burned Chambersburg".[107]

Resigns

[edit]Powell resigned from the Union Army on January 5, 1865, because of family issues.[92] His father had died and his mother was seriously ill.[3] He issued a farewell address on January 10. In accepting the resignation on January 14, Torbert wrote of his "appreciation of your valor and ability as a soldier, your zeal, efficiency and untiring energy as a cavalry commander."[92] Sheridan thanked Powell for his "faithful support, and for your gallantry which has contributed so much to make the victories of the Shenandoah Valley decisive."[108] A tribute to Powell by Sheridan and officers from Powell's division was published on the front page of a Wheeling newspaper.[109] Five days later, the same newspaper published a biographical sketch and Powell's farewell address.[110]

During the American Civil War, Powell was involved in 61 battles and engagements, and rose from captain to brigadier general.[15] On February 24, 1866, Powell was nominated to be appointed to major general of the volunteers by brevet. The appointment was retroactive to March 13, 1865, and was for "gallant and meritorious services during the campaign of 1864 in West Virginia, and particularly at the battle of Front Royal."[111][Note 12]

Animosity with Confederacy

[edit]

Powell was strongly disliked by supporters of the Confederacy. No matter what his rank was, he was often leading Union cavalry attacks.[Note 13] Weather and terrain were not deterrents to Powell's aggression, as proven in the 1862 Sinking Creek raid.[32] Powell had been accused by Confederate General Sam Jones of shooting a prisoner "in cold blood". In another incident, he was accused of setting fire to a home with a family asleep inside. Powell became "one of the Confederacy's most wanted Union officers".[115]

After Powell was wounded and captured in Wytheville, he was eventually moved to Libby Prison and initially kept in a dungeon.[55] Jones, who was the general in command of Confederate army regional headquarters in western Virginia, wrote at that time that Powell "is a bold, daring man, and one of the most dangerous officers we have had to contend with in the northwest of the state, and I am particularly anxious that he should not be allowed to return to the Kanawha Valley if it can be avoided."[52]

As a division commander, Powell ordered the execution of at least three prisoners in retaliation for what he considered the murder of his men by bushwhackers. He called the bushwhackers "illegal and outlawed bands of horse-thieves and murderers, recognized and supported by rebel authorities".[116] The treatment of bushwhackers by both Custer and Powell caused Mosby to write an open letter to Sheridan threatening retaliation.[117] Powell reported that he would not be intimidated by threats from the Richmond press.[118] He wrote that he wished it be known to rebel authorities that if hanging two rebels for every one of his men murdered by bushwhackers was not enough, "I will increase it to twenty-two to one".[116] Contrary to newspaper reports that stated Powell resigned because of family issues, one source believes that Powell was dismissed from active duty because one of the rebels he executed was related to former Senator John Crittenden, Union General Thomas L. Crittenden, and Confederate General George Crittenden.[119] In Powell's farewell speech, he said "No one regrets the existence of the cause that necessitates the act more than I."[110]

Post war

[edit]

After leaving the military, Powell returned to the iron and nail business, becoming general manager of the Ironton Rolling Mill in Ironton, Ohio.[68] He declined a Republican nomination for congress.[119] In the spring of 1867, he moved to Clifton, West Virginia, to form the Clifton Nail Works, which he managed. His Clifton home is now part of the National Register of Historic Places.[120] In the Presidential election of 1868, Powell was a Ulysses S. Grant elector in the Electoral College.[119]

In 1870, Powell was almost killed in a horse and buggy accident, and was unable to work in the iron works business.[5] He sold his interest in the nail works, and moved to Kansas City, Missouri.[68] At Kansas City, Powell worked for Standard Oil until he moved to St. Louis and worked for American Central Insurance.[3]

In 1876, Powell had recovered enough from his accident that he could work in the iron/nail business again.[68] This time, he moved to Belleville, Illinois, where he lived for the rest of his life. He became one of the town's most respected citizens.[121] Powell was manager of the Waugh Company Nail Works until 1882, when he organized the Western Nail Works. He worked at this Belleville company, as president, superintendent and general manager, until 1892. During this time, one source claimed that Powell had "more intimate practical knowledge of the nail business than any other man in the United States".[122] Two years after Powell's move to Belleville, his wife Sara died. She had been diagnosed with cancer, and died seven months later while only 54 years old.[121] A year later in 1879, he married local resident Emma Weaver.[3]

Powell was acquainted with two Presidents: Hayes, and a long-time friend William McKinley—they all fought in the Army of West Virginia during the Civil War. McKinley also came from an iron-making family, and appointed Powell as an Internal Revenue Collector in 1895. Powell was a strong participant in a fraternal organization of Civil War veterans that fought for the Union, the Grand Army of the Republic. He was the Illinois department commander for that organization in 1895 and 1896.[3]

The bullet that wounded Powell in Wytheville was never removed. It was lodged in his lung, and contributed to health difficulties that included rheumatism and respiratory problems.[121] Powell died at his home in Belleville on December 26, 1904. He was survived by his wife and three of his children.[123] Powell is buried at Chicago's Graceland Cemetery.[124]

Notes

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ The major issues that caused the American Civil War were slavery and the rights of states. In the north, abolitionists believed slavery was immoral and should not exist. The southern states believed that the northern abolitionists were interfering with states' rights.[7] In the south, Africans (the slaves), with their natural resistance to malaria, were a superior labor force for harvesting crops that were essential to the southern economy.[8] Thus, the northern reason for seeking change was morality, while the southern reason for keeping the status quo was economic.[9]

- ^ Criteria for awarding the Medal of Honor changed over the years, and the award became more difficult to receive beginning in 1897.[37] During the American Civil War, capturing a flag almost always earned someone a Medal of Honor.[38] In those cases, the medal was awarded soon after the event occurred. For example, Private Joseph Kimball of Company B of the 2nd West Virginia Cavalry was issued his medal on May 3, 1865, for "Capture of flag of 6th North Carolina Infantry" at Sailors Creek on April 6, 1865.[39] Medals for actions other than the capture of a flag were not always awarded immediately. For example, Colonel Henry Capehart rescued a drowning soldier, under enemy fire, after both had gone over a waterfall.[40] This happened on March 22, 1864. Capehart was not awarded his Medal of Honor until February 12, 1895.[41] Like Capehart, Powell did not receive his Medal of Honor until many years after the war. His citation says "Distinguished services in raid, where with 20 men, he charged and captured the enemy's camp, 500 strong, without the loss of man or gun."[42]

- ^ Powell's health issues may have been a cover for his dissatisfaction with the popular Paxton, who he described as a "drunken commander". In a confidential letter written on May 1, 1863, he discussed his resignation, Paxton's drinking, and wrote "I cannot remain longer under Col. Paxton's administration."[45]

- ^ The Union and Confederate surgeons believed Powell was mortally wounded.[49] However, sources disagree on how Powell was wounded. The report of Major John J. Hoffman says Powell was accidentally shot by one of his own men. However, some witnesses believe he was shot by a Wytheville citizen stationed inside a house.[50] A letter written shortly after the war by Captain William Fortescue, of the 2nd West Virginia Cavalry's Company I, briefly discussed the shooting of both colonels. Powell rode with Company I in the initial charge into town. Fortescue did not mention any friendly fire accident connected to Powell.[51]

- ^ Lang's book describes the presentation to Powell in Ironton.[56] A brace of revolvers is a pair of handguns. In this case, the revolvers were capable of firing six shots each before needing to be reloaded.[57]

- ^ Sources do not agree on the extent of Averell's and Duffié's participation in the battle. Sutton, who was in the 2nd West Virginia Cavalry, wrote that "General Averell was slightly wounded early in the engagement by a ball cutting the skin across his forehead, causing some inconvenience from the freedom with which it bled."[60] Lang says that "Averell received a wound across his forehead compelling his retirement from command during the battle, and in view of General Duffié's conspicuous absence, the command devolved upon Colonel Powell...."[61] Duncan says "Despite suffering a minor injury across his forehead, Averell continued to direct his men.".[62]

- ^ The detour and fighting were described by a private in the 2nd (West) Virginia Cavalry.[64] The participation in the detour by a local slave was described by journalist John M. Johnson.[65] Although President Lincoln had issued the Emancipation Proclamation that freed slaves in the rebellious states earlier in the year, it was ignored by the Confederate states such as Virginia and did not apply to the nearby western Virginia counties that would eventually become West Virginia.[66]

- ^ Sutton says Powell's brigade consisted of the 1st and 2nd West Virginia cavalries, and the 3rd West Virginia Cavalry was assigned to a division under the command of Crook.[67] This source has been used herein because Sutton participated in the battle. Lang says that the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd West Virginia cavalries were part of Powell's brigade.[61] A third source also lists the three West Virginia regiments as being under the command of Powell.[68]

- ^ One of General Duffié's cavalry brigades fled north panic-stricken, and this panic spread to teamsters pulling supplies north. Many of the teamsters abandoned their wagons after setting them on fire, and rode their horses away from the battle.[76] Duffié became separated from his command during the darkness of a night rain.[77]

- ^ The First Brigade consisted of the 8th Ohio Cavalry, the 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry, and the 22nd Pennsylvania Cavalry. Their brigade commander was Colonel James M. Schoonmaker. The Second Brigade consisted of the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd West Virginia Cavalry Regiments, plus the 1st New York (Lincoln) Cavalry. This brigade was commanded by Colonel Henry Capehart. Powell's artillery was Battery L, Fifth U.S. Artillery, which was commanded by Lieutenant Gulian V. Weir.[93]

- ^ Powell's report says September 27, and another source says September 26.[94][95]

- ^ Although Powell was breveted for actions at the "battle of Front Royal", he was fighting near Lewisburg, Virginia (now West Virginia), during May 1862 when the Battle of Front Royal took place.[112][113] His division was based in Front Royal during the Battle of Cedar Creek and the nearby Battle of Nineveh in late 1864.[93]

- ^ Examples of Powell's leadership against the Confederates include leading the advance guard as a major when it attacked the larger Confederate cavalry commanded by Colonel Albert Jenkins near Barboursville,[27] burning a mountaintop barn and home (as ordered) as a lieutenant colonel,[114] and commanding the first attackers in the Wytheville Raid as a colonel.[48]

Citations

[edit]- ^ Eicher, Eicher & Simon 2001, p. 438

- ^ a b Lang 1895, p. 181

- ^ a b c d e f g "William H. Powell Papers, 1825-1899, Chronicling Illinois". Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum. Archived from the original on April 17, 2015. Retrieved January 1, 2017.

- ^ a b Bonham 1883, p. 330

- ^ a b c Bonham 1883, p. 331

- ^ Reid 1868, p. 909

- ^ Stampp 1991, p. 19

- ^ Mann 2011, p. 43

- ^ Mann 2011, p. 137

- ^ "Civil War Facts". Civil War Trust. August 16, 2011. Retrieved June 25, 2017.

- ^ "First Session of the Second Wheeling Convention". West Virginia Division of Culture and History. Retrieved January 2, 2017.

- ^ Barker 2003, p. 4

- ^ Sutton 2001, p. 50

- ^ a b Sutton 2001, p. 48

- ^ a b United States 1891, p. 1

- ^ Sutton 2001, pp. 50–51

- ^ Sutton 2001, p. 56

- ^ Mountcastle 2009, p. 106

- ^ Lang 1895, p. 182

- ^ Magid 2011, p. 125

- ^ a b Sutton 2001, p. 53

- ^ Sutton 2001, p. 55

- ^ Wallace 1897, p. 183

- ^ a b Sutton 2001, p. 59

- ^ Schmiel 2014, p. 54

- ^ "West Virginia History - The Civil War Record of Albert Gallatin Jenkins, C. S. A." West Virginia Division of Culture and History. Retrieved February 17, 2017.

- ^ a b c Sutton 2001, p. 60

- ^ "Campaign in the Kanawha Valley, W. Va". West Virginia Division of Culture and History. Retrieved July 22, 2015.

- ^ Black 2004, p. 80

- ^ Wallace 1897, p. 185

- ^ "Sinking Creek Raid Official Records". West Virginia Division of Culture and History. Retrieved February 15, 2015.

- ^ a b Sutton 2001, p. 65

- ^ Lang 1895, p. 185

- ^ Sutton 2001, p. 69

- ^ Sutton 2001, p. 70

- ^ Wallace 1897, p. 191

- ^ Editors of Boston Publishing Company 2014, p. 94

- ^ Editors of Boston Publishing Company 2014, p. 47

- ^ "Medal of Honor Recipients - Civil War (G-L) Kimball, Joseph". U.S. Army Center of Military History. Retrieved December 26, 2017.

- ^ Beyer & Keydel 1907, pp. 344–345

- ^ "Medal of Honor Recipients - Civil War (A-F) Capehart, Henry". U.S. Army Center of Military History. Retrieved December 20, 2017.

- ^ "Medal of Honor Recipients - Civil War (M-R) Powell, William H." U.S. Army Center of Military History. Retrieved December 26, 2017.

- ^ a b Lang 1895, p. 186

- ^ Sutton 2001, p. 73

- ^ "Confidential Camp Piatt May 1, 1863 (hand written letter)". West Virginia Division of Culture and History. Retrieved December 27, 2015.

- ^ Sutton 2001, p. 81

- ^ Lang 1895, p. 187

- ^ a b Sutton 2001, p. 89

- ^ a b Walker 1985, p. 60

- ^ Rolston 2017, p. 86

- ^ Pendleton 1920, p. 619

- ^ a b Sutton 2001, pp. 103–104

- ^ Whisonant 2015, p. 80

- ^ Walker 1985, p. 56

- ^ a b c Sutton 2001, p. 102

- ^ Lang 1895, p. 188

- ^ Morgan 2013, p. 7

- ^ Sutton 2001, p. 112

- ^ Sutton 2001, p. 113

- ^ a b c Sutton 2001, p. 115

- ^ a b c Lang 1895, p. 189

- ^ Duncan 1998, p. 81

- ^ "Battle Summary: Cover Mountain, VA". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved March 18, 2017.

- ^ Sutton 2001, p. 116

- ^ "The Battle of Cove Mountain". The Mountain Laurel - The Journal of Mountain Life. Retrieved October 25, 2017.

- ^ "Celebrating West Virginia Statehood, June 20, 1863". The U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. August 15, 2016. Retrieved October 25, 2017.

- ^ a b Sutton 2001, p. 126

- ^ a b c d e Unlisted (The Cambrian) 1882, p. 116

- ^ Lang 1895, p. 190

- ^ "Battle Summary: Lynchburg, VA". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved March 23, 2017.

- ^ a b Sutton 2001, p. 134

- ^ Sutton 2001, p. 138

- ^ "Rutherford's Farm". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved March 30, 2017.

- ^ Sutton 2001, p. 140

- ^ "Battle Summary: Kernstown, Second". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved March 31, 2017.

- ^ Patchan 2007, p. 244

- ^ Patchan 2007, pp. 254–255

- ^ Patchan 2007, p. 253

- ^ Patchan 2007, p. 255

- ^ Sutton 2001, p. 150

- ^ Ainsworth & Kirkley 1902, pp. 494–495

- ^ "Battle Detail - Moorefield". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved April 3, 2017.

- ^ "12. OPEQUON or Third Winchester (19 September 1864)". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved April 15, 2017.

- ^ Patchan 2007, p. 314

- ^ "Battle Detail - Opequon". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved September 12, 2015.

- ^ Sutton 2001, p. 160

- ^ "13. FISHER'S HILL (21-22 September 1864)". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved April 15, 2017.

- ^ Sheridan 1992, p. 44

- ^ a b c Sutton 2001, p. 161

- ^ Lang 1895, p. 191

- ^ Lang 1895, pp. 191–192

- ^ a b c Lang 1895, p. 192

- ^ a b c Ainsworth & Kirkley 1902, p. 506

- ^ a b c d Ainsworth & Kirkley 1902, p. 507

- ^ a b c d e Reid 1868, p. 515

- ^ Simson 2008, p. 84

- ^ a b c d Ainsworth & Kirkley 1902, p. 508

- ^ a b c Ainsworth & Kirkley 1902, p. 509

- ^ "Battle Detail - The Battle of Cedar Creek". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved December 26, 2015.

- ^ Farrar 1911, p. 412

- ^ Farrar 1911, p. 414

- ^ Sutton 2001, p. 170

- ^ Farrar 1911, p. 435

- ^ Beach 1902, pp. 448–449

- ^ Beach 1902, p. 450

- ^ Rhodes 1900, p. 149

- ^ a b "Camp Near Winchester, VA., Nov. 12 1864". Wheeling Daily Intelligencer. November 23, 1864. p. 1.

- ^ Lang 1895, p. 193

- ^ "BRIG GEN'L WM H.POWELL". Wheeling Daily Intelligencer. January 20, 1865. p. 1.

Tribute of Respect from his Late Comrades in Arms

- ^ a b "Biographical Sketch of Brig. Get. W. H. Powell, formerly Colonel of the 2nd West Virginia Cavalry...". Wheeling Daily Intelligencer. January 25, 1865. p. 1.

We have already noticed the resignation of this gallant officer, soloing an honor to the West Virginia service....

- ^ United States, Congress & Senate 1887, pp. 744–745

- ^ "3. FRONT ROYAL (23 May 1862)". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved June 22, 2017.

- ^ Sutton 2001, p. 54

- ^ Sutton 2001, p. 72

- ^ Rolston 2017, p. 85

- ^ a b Ainsworth & Kirkley 1902, p. 511

- ^ "Retaliation by Colonel Mosby". Richmond Daily Dispatch. November 21, 1864. p. 2.

- ^ Ainsworth & Kirkley 1902, p. 510

- ^ a b c Rolston 2017, p. 88

- ^ "National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form - Powell-Redmond House" (PDF). West Virginia Division of Culture and History (United States Department of the Interior). Retrieved September 20, 2017.

- ^ a b c Rolston 2017, p. 89

- ^ Bonham 1883, p. 334

- ^ "William H. Powell Obituaries". West Virginia Division of Culture and History. Archived from the original on May 13, 2006. Retrieved January 3, 2022.

- ^ Grand Army of the Republic Department of Illinois Encampment 1905, p. 216

References

[edit]- Ainsworth, Fred C.; Kirkley, Joseph W. (1902). The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies Series I Volume XLIII Part 1. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. OCLC 427057.

- Barker, Bret (2003). Exploring Civil War Wisconsin : a Survival Guide for Researchers. Madison, WI: Wisconsin Historical Society Press. ISBN 978-0-870203-39-8. OCLC 51293542.

- Beach, William Harrison (1902). The First New York (Lincoln) Cavalry from April 19, 1861, to July 7, 1865. New York: Lincoln Cavalry Association. OCLC 44089779.

- Beyer, Walter F.; Keydel, Oscar F. (1907). Deeds of Valor : from Records in the Archives of the United States Government ; How American Heroes Won the Medal of Honor ; History of our Recent Wars and Explorations, from Personal Reminiscences and Records of Officers and Enlisted Men who were Rewarded by Congress for Most Conspicuous Acts of Bravery on the Battle-field, on the High Seas and in Arctic Explorations Volume I. Detroit: Perrien-Keydel Co. OCLC 3898179.

- Black, Robert W. (2004). Cavalry Raids of the Civil War. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-811731-57-7. OCLC 231993075.

- Bonham, Jeriah (1883). Fifty Years' Recollections: with Observations and Reflections on Historical Events, Giving Sketches of Eminent Citizens -- Their Lives and Public Services. Peoria, IL: J.W. Franks & Sons. OCLC 3262599.

- Duncan, Richard R. (1998). Lee's Endangered Left: The Civil War in western Virginia, spring of 1864. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 978-0-807130-18-6. Retrieved March 20, 2017.

- Editors of Boston Publishing Company (2014). The Medal of Honor: A History of Service Above and Beyond. Minneapolis, MN: Zenith Press. ISBN 978-0-76034-624-2. OCLC 881386338.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help) - Eicher, John H.; Eicher, David J.; Simon, John Y. (2001). Civil War High commands. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-804780-35-3. OCLC 923699788.

- Farrar, Samuel Clarke (1911). The Twenty-second Pennsylvania Cavalry and the Ringgold Battalion, 1861-1865. Akron, OH and Pittsburgh: New Werner Co. OCLC 1211514.

- Grand Army of the Republic Department of Illinois Encampment (1905). Proceedings of the Thirty-Ninth Annual Encampment of the Department of Illinois G. A. R. Chicago: M. Umbdenstock. OCLC 21898325.

- Lang, Joseph J. (1895). Loyal West Virginia from 1861 to 1865 : with an introductory chapter on the status of Virginia for thirty years prior to the war. Baltimore, MD: Deutsch Publishing Co. OCLC 779093.

- Magid, Paul (2011). George Crook: From the Redwoods to Appomattox. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-8593-4. OCLC 812924966.

- Mann, Charles C. (2011). 1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created. New York: Knopf. ISBN 978-0-3072-6572-2. OCLC 682893439.

- Morgan, Michael (2013). Handbook of Modern Percussion Revolvers. Iola, Wisconsin: Krause Publications. ISBN 978-1-440238-98-7. OCLC 840465312.

- Mountcastle, Clay (2009). Punitive War: Confederate Guerrillas and Union Reprisals. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-1668-8.

- Patchan, Scott C. (2007). Shenandoah Summer: The 1864 Valley Campaign. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-0700-4. OCLC 122563754.

- Pendleton, William C. (1920). History of Tazewell County and Southwest Virginia, 1748–1920. Richmond, VA: W. C. Hill Printing Co. OCLC 1652100.

- Reid, Whitelaw (1868). Ohio in the War; Her Statesmen, Her Generals, and Soldiers Vol. I. Cincinnati: Moore, Wilstach & Baldwin. OCLC 444862.

- Rhodes, Charles D. (1900). History of the Cavalry of the Army of the Potomac including that of the Army of Virginia (Pope's) and also the History of the Operations of the Federal Cavalry in West Virginia During the War. Kansas City, MO: Hudson-Kimberly Publishing Co.

- Rolston, Les (2017). HOME OF THE BRAVE : In their Own Words, Selected Short Stories of Immigrant Medal of Honor... Recipients of the Civil War. Litchfield, IL: Revival Waves of Glory Books and Publishing. ISBN 9781365837388. OCLC 986905148.

- Schmiel, Gene (2014). Citizen-General : Jacob Dolson Cox and the Civil War Era. Athens, OH: Ohio University Press. ISBN 978-0-8214-2082-9. OCLC 861676486.

- Sheridan, Philip Henry (1992) [1888]. Personal Memoirs of P. H. Sheridan, General, United States Army. Wilmington, N.C.: Broadfoot Pub. ISBN 978-1568370-48-4. OCLC 27574500.

- Simson, Jay W. (2008). Crisis of Command in the army of the Potomac: Sheridan's Search for an Effective General. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co. ISBN 978-0786436-53-8. OCLC 182656596.

- Stampp, Kenneth (1991). The Causes of the Civil War: Revised Edition. New York: Touchtone. ISBN 978-0-6717-5155-5.

- Sutton, Joseph J. (2001) [1892]. History of the Second Regiment, West Virginia cavalry volunteers, during the war of the rebellion. Huntington, WV: Blue Acorn Press. ISBN 978-0-9628866-5-2. OCLC 263148491.

- United States; Congress; Senate (1887). Journal of the Executive Proceedings of the Senate of the United States of America Volume XIV Part II. Washington: Government Printing Office. OCLC 2263101.

- United States (1891). Reports of Committees of the House of Representatives for the Second Session of the Fifty-First Congress, 1890-'91. Washington: Government Printing Office. OCLC 3888071.

- Unlisted (The Cambrian) (1882). The Cambrian : A Bi-monthly Published in the Interest of the Welsh People and their Descendents in the United States : Devoted to History, Biography, and Literature Volume II Issue 3. Cincinnati, Ohio: D. I. Jones. OCLC 2054012.

- Walker, Gary C. (1985). The War in Southwest Virginia, 1861–65. Roanoke, VA: Gurtner Graphics and Print. Co. OCLC 12703870.

- Wallace, Lew (1897). The story of American heroism : thrilling narratives of personal adventures during the great Civil War, as told by the medal winners and roll of honor men. St. Louis: Riverside Publishing. OCLC 26199770.

- Whisonant, Robert C. (2015). Arming the Confederacy : How Virginia's Minerals Forged the Rebel War Machine. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. ISBN 978-3-319-14508-2. OCLC 903929889.

External links

[edit]- 1825 births

- 1904 deaths

- American Civil War recipients of the Medal of Honor

- People from Ironton, Ohio

- People from Pontypool

- People of Ohio in the American Civil War

- Union army soldiers

- United States Army Medal of Honor recipients

- Welsh-born Medal of Honor recipients

- Welsh emigrants to the United States

- Burials at Graceland Cemetery (Chicago)

- Grand Army of the Republic officials