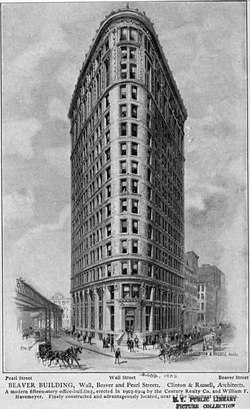

Clinton and Russell

Clinton and Russell was a well-known architectural firm founded in 1894 in New York City, United States. The firm was responsible for several New York City buildings, including some in Lower Manhattan.

Biography

[edit]Charles W. Clinton (1838–1910) was born and raised in New York and received his formal architectural training in the office of Richard Upjohn. He left Upjohn in 1858 to begin a private practice, and from then through 1894 he conducted his own significant career, the highpoint of which was probably the 1880 Seventh Regiment Armory.

William Hamilton Russell (1856–1907) was born in New York City as well. He attended the Columbia School of Mines before he joined his great uncle, James Renwick, in his architecture firm in 1878. At Columbia, Russell had been a member of St. Anthony Hall, the secret fraternal college society, and within a year of his joining his great uncle's firm, in 1879, Renwick completed the first St. A's Chapter House, at 25 East 28th Street, likely with Russell involved in the design work.[1]

In New York City's ambitious building boom c. 1900, Clinton and Russell were responsible for designing the world's largest apartment building, the world's largest office building, and a cluster of early downtown skyscrapers along Broadway and Wall Street for banks and insurance companies. Many of the firm's important commissions related to real estate investments of the Astor family. The landmark Astor Hotel that served as an anchor for the development of Times Square, the Astor Apartments, the Graham Court Apartments, and The Apthorp were among their projects for William Waldorf Astor, 1st Viscount Astor. Stylistically, much of their work conformed to a conservative Italian Neo-Renaissance style.[2]

After the deaths of the principals, the firm continued in business, and in 1926 it was renamed Clinton Russell Wells Holton & George (and variations of that name). For a time the English-born Colonel James Hollis Wells (1864-1926) headed the organization; the Lillian Sefton Dodge Estate on Long Island is his design. The firm remained in existence until 1940.

Employees

[edit]One of the firm's earliest employees was Abraham H. Albertson, who started there as a draftsman and went on to be a prolific architect in Seattle.[3]

Notable works

[edit]- Fahys Building, 52-54 Maiden Lane, 1894–96 (razed)

- Sampson Building, 63-65 Wall Street, 1898 (razed)[4]

- Hudson Building, 32-34 Broadway, 1896–98

- Exchange Court Building, 52-56 Broadway, 1896–98 (altered, now the Exchange Apartments)[4]

- Woodbridge Building, William and Platt Streets, NYC, 1898 (razed in 1970)

- Curzon House, facade redesign of #4 East 62nd Street, NYC,[5] 1898

- the Franklin Building, 9-15 Murray Street, 1898

- the Chesebrough Building, 13-19 State Street, Battery Park, NYC, 1899 (razed)[6]

- Graham Court Apartments,[5] 1899-1901

- Medbery Hall, Dorm Building for Hobart College, 1900

- Broad Exchange Building, #25 Broad Street, New York City, 1900

- Coxe Hall, Administrative and Classroom Building for Hobart College, 1901

- American Exchange National Bank Building 128 Broadway, 1901 (razed)

- the 18-story Atlantic Building, aka the Mutual Insurance Building, Wall and William Streets, 1901[7]

- Astor Apartments,[5] 1901-1905

- Wall Street Exchange Building, 43-49 Exchange Place, 1903[4]

- 1 Wall Street Court,[2][5][8] 1904

- Hotel Astor, New York City, 1904, expanded 1909-1910 (razed 1967)

- 71st Infantry Regiment Armory, Park Avenue and 34th Street, NYC, 1905 (razed 1976)

- The Langham Apartments,[5] one of the towering apartment buildings lining Central Park West between West 73rd and West 74th Streets, 1905-1907

- U.S. Express Company Building, 2 Rector Street, 1905–07

- The Apthorp Apartments,[5] briefly the largest apartment building in the world, NYC, 1906-1908

- Consolidated Stock Exchange Building, 61-69 Broad Street, 1907 (razed)

- Lawyers' Title Insurance & Trust Company, 160 Broadway, NYC, 1908[7]

- the 31-story Whitehall Building Annex,[5] 1908-1910

- the Hudson Terminal in lower Manhattan, the world's largest office building by floor area when built in 1908, razed in 1972 for the World Trade Center

- Whyte's Restaurant, Fulton Street, designed as a "half-timbered English village inn", 1910[7]

- redesign of Clarence True's 103-104 Riverside Drive,[5] 1910-1911

- Otis Elevator Building, 260 Eleventh Avenue, 1911-1912[9]

- East River Savings Bank Building, NW corner of Broadway and Reade Streets, 1911[7]

- portions of the Elks National Home, Bedford, Virginia, 1916

- The Lenox Hotel (later The Lenox Apartments; now, The Lenox Condominiums), 1917. 250 S. 13th Street (at Spruce Street) Philadelphia, PA

- Mecca Masonic Temple (1923) in collaboration with the architect Harry P. Knowles,[5] now known as New York City Center

- Lillian Sefton Dodge Estate, Mill Neck, Nassau County, New York,[10] 1923

- The Level Club, New York City,[5] 1927

- Herald Square Building, 1350 Broadway, New York City, 1928-1930

- Cities Service Building/American International Building, 70 Pine Street, New York City, 1930-1932[5]

- 7 East 67th Street facade.[5]

References

[edit]- ^ Gray, Christopher (2 September 1990). "Streetscapes: Readers' Questions; of Consulates, Stores and Town Houses". The New York Times.

- ^ a b Beaver Building Designation Report Archived 2012-10-10 at the Wayback Machine," (PDF), New York Landmarks Preservation Commission, 13 February 1996. Retrieved 6 April 2007.

- ^ Ochsner, Jeffrey Karl (May 1, 2017). Shaping Seattle Architecture: A Historical Guide to the Architects, Second Edition. University of Washington Press. pp. 198–200. ISBN 978-0-295-80689-1. Retrieved December 31, 2019.

- ^ a b c "Beaver Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. February 13, 1996. Retrieved 2020-10-13.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l White, Norval & Willensky, Elliot; AIA Guide to New York City, 4th Edition; New York Chapter, American Institute of Architects; Crown Publishers/Random House. 2000. ISBN 0-8129-3106-8; ISBN 0-8129-3107-6. p.267.

- ^ Biographical dictionary of American architects (deceased), Henry F. Withey and Elsie Rathburn Withey

- ^ a b c d New York 1900, Robert A.M. Stern

- ^ http://www.oprhp.state.ny.us/hpimaging/hp_view.asp?GroupView=5590 Archived 2011-07-24 at the Wayback Machine Central Park West Historic District], (Java), National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form, New York's State and National Registers of Historic Places Document Imaging Project [1] Archived 2005-11-12 at the Wayback Machine, New York State Historic Preservation Office. Retrieved 6 April 2007.

- ^ AIA Guide to New York City By Norval White, Elliot Willensky, Fran Leadon

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.