Wilbur Olin Atwater

Wilbur Olin Atwater | |

|---|---|

Atwater's USDA portrait | |

| Born | May 3, 1844 |

| Died | September 22, 1907 (aged 63) Middletown, Connecticut, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | Wesleyan University (BA) Yale University (PhD) |

| Known for | Atwater system, studies of human nutrition and metabolism |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Chemistry |

Wilbur Olin Atwater (May 3, 1844 – September 22, 1907) was an American chemist known for his studies of human nutrition and metabolism, and is considered the father of modern nutrition research and education. He is credited with developing the Atwater system, which laid the groundwork for nutrition science in the United States and inspired modern Olympic nutrition.[1]

Atwater was director of the first United States Agricultural Experiment Station at Wesleyan University in Middletown, Connecticut and he was the U.S. Department of Agriculture's first chief of nutrition investigations.[2]

Early life

[edit]Atwater was born in Johnsburg, New York, the son of William Warren Atwater, a Methodist Episcopal minister, temperance advocate, and librarian of Yale Law School and Eliza (Barnes) Atwater.[3] He grew up in, and spent much of his life in New England. He opted not to fight in the American Civil War, instead pursuing his undergraduate education, first at the University of Vermont and then moving to Wesleyan University in Connecticut, where he would complete his general education in 1865.[4] For the next three years, Atwater was a teacher at various schools and in 1868, he enrolled in Yale University's Sheffield Scientific School, where he studied agricultural chemistry under William Henry Brewer and Samuel William Johnson.[5][6] During his time at Yale, Atwater worked part time as Johnson's assistant analyzing fertilizers for specific mineral content; he also performed the first chemical analysis of food or feed in the United States.[5] Atwater received his doctorate in 1869 in agricultural chemistry, his thesis was entitled The Proximate Composition of Several Types of American Maize, in it he used variations of the proximate analysis system to analyze four varieties of corn. Afterwards, he continued his education for the next two years in Leipzig and Berlin, studying physiological chemistry and acquainting himself with the agricultural experiment stations of Europe.[2] During his time there, Atwater studied under German physiologist and dietitian, Carl von Voit and worked alongside Voit's student, Max Rubner.[7] Atwater spent time traveling throughout Scotland, Rome, and Naples; on his trip he wrote articles about his observations for local newspapers based in the places he had lived in the United States. In 1871, Atwater returned to the United States to teach chemistry at East Tennessee University and the next year moved to Maine State College.[8]

While there, Atwater met Marcia Woodard (1851-1932) of Bangor, Maine, the daughter of Abram Woodard.[3] They married in 1874 and in 1876, their daughter Helen was born and son Charles was born in 1885.[3]

Career

[edit]

Wilbur Atwater returned to Wesleyan as a professor of chemistry in 1873 and remained there until his death in 1907.[9] Both he, and his mentor from Yale, Samuel Johnson, were proponents of bringing organizations to the United States similar to the agricultural experiment stations they saw in Europe.[10][11] Atwater even described the German agricultural experiment stations in an 1875 report to the Department of Agriculture.[12] To persuade the Connecticut legislature to appropriate money for a station, Orange Judd donated funds and Wesleyan offered laboratory facilities and Atwater's services on a part-time basis.[8] Through their work and a $5,600 contribution from the Connecticut legislature for a two-year trial period, the first agricultural experiment station was created in the United States.[5][13]

Atwater served as administrator of the trial run from 1875 until 1877 with initial research focused on fertilizers.[9][7] Before the two year trial was over, the Connecticut legislature agreed to regular funding of the station but had decided to move the permanent Connecticut Experiment Station to the Sheffield Scientific School at Yale with Samuel Johnson as first director.[5] During this time, Atwater wrote numerous articles for scientific periodicals detailing his research and findings in physiological and agricultural chemistry and on research being conducted abroad (specifically in Germany).[3][5] Many of his articles appeared in a column called "Science Applied to Farming", mostly discussing agricultural fertilizers in Orange Judd's American Agriculturalist.[3][5]

During the initial phase of the first experiment station, Atwater expanded his fertilizer program and began to study and experiment with the growth and composition of field crops.[8] The field crop research continued even after the appropriation ceased on a nearby farm; Atwater became particularly interested in plant metabolism and was one of the first researchers to provide proof that legumes assimilate nitrogen from the air.[8]

As his experiments and accomplishments became known, Atwater's assistance was requested for a variety of projects. From 1879 to 1882, he conducted extensive human food studies on behalf of the United States Fish Commission and Smithsonian Institution.[6][2] In 1879, the U.S. Fish Commission offered Atwater funds to study the composition and nutritional value of North American species of fish and invertebrates.[6] For the 1882-1883 school year, Atwater took a leave of absence from Wesleyan to study the digestibility of lean fish with von Voit in Germany.[8] Together, they found fish comparable to lean beef; during this time he became aware of how German scientists were studying nutrition and hoped to bring similar research to the United States upon his return.[8] In 1885, Atwater's first series of studies on peas grown in nutrient solution were published in the American Chemical Journal. That same year, the Massachusetts Bureau of Statistics of Labor requested a study of data that had been collected by the bureau concerning family food purchases.[8] In the study, Atwater calculated the daily per capita supplies of carbohydrates, fat, and protein provided within the data, and taking into account the included cost data, made recommendations on how more economical diets, while still having adequate nutritional value, could be chosen.[8] The report he prepared was included in the Bureau's 1886 Annual Report.

Throughout this time, Atwater continued to campaign and support the expansion of state agricultural experiment stations.[7] Due to their European research and experience with the government-funded European experiment stations, Atwater and Johnson had become consultants to the USDA and vocal promoters of federally regulated and funded agricultural research.[13] Atwater had even begun writing in USDA publications in support of adopting the European model of scientific laboratories in domestic experiment stations. By 1885, Atwater and Johnson had begun advising Congress and President Grover Cleveland on the creation of experiment stations at the land-grant colleges created through the Morrill Act in 1862.[7] In 1887, the Hatch Act was passed, which gave federal funds ($15,000 each) to the land-grant colleges to create experiment stations.[14][15] As the Act was passed, Atwater was named director of the second agricultural experiment station in Connecticut that was established at Storrs Agricultural College, and he served there until 1892.[3] The following year, the Office of Experiment Stations was created as a means to monitor and appraise the experiments and activities of the stations; Atwater was chosen as the first director.[16][8][13] He accepted the position on the condition of being able to maintain both his professorship, and his position of director of the Storrs Agricultural Experiment Station.[8][16] Atwater spent about 8 months of the year in Washington and had deputies act for him in his other positions during his absence.[5]

Atwater saw his mission as director of the Office of Experiment Stations to be "to bring the stations throughout the country together, to unify their work, and to put them into communication with the great world of science."[17] He immediately established a journal, the Experiment Station Record, meant to be a means of keeping the stations abreast of the scientific research being conducted by their colleagues and scientists abroad.[8] Atwater made clear that the publication was meant to be a collection of scientific papers and not a platform for swapping farm tips.[13] The publication was a means for the Hatch Act stations to report their research to the USDA, while also holding scientists accountable to particular standards of research and reporting.[13] At the same time, Farmers' Bulletins were created to provide farmers with an easy to read and understand presentation of the findings of agricultural research stations and other scientific institutions.[8] Through Atwater's role as director he was able to guide agricultural experiment station research towards scientific and experiment based methods.[13]

Nutrition research and innovation

[edit]Throughout his career, Atwater had been interested in human nutrition studies; having conducted the studies on behalf of the U.S. Fish Commission and the Smithsonian Institution, he had continued human nutrition research and the Storrs experiment station became known for nutritional studies.[13] Once the Storrs station was created, Atwater and his colleagues had begun conducting and publishing studies on the chemical compositions of food.[18][13] In 1891, he resigned as director of the Office of Experiment Stations in order to return to the Storrs and focus exclusively on nutrition research.[5][8] After his resignation, Atwater was appointed special agent in charge of nutrition programs. Through this position he organized extensive food analyses, dietary studies, experiments on the digestibility of food, investigations of energy requirements using human subjects, and studies of the cost and economics of food use and production.[17][8] In 1894, Atwater received his first congressional appropriation, allocated to his laboratory for human nutrition research.[13] Atwater's studies during this time were used to create dietary standards. He based the standards off of average intakes, but did not regard them as quantitatively accurate; they logically varied based on age, sex, and activity level but he stressed that they were not metabolic studies.[16][19]

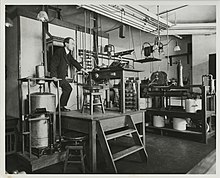

He went on to conduct metabolic studies related to the dietary standards, based on observations from his work with Voit, who had used a Rubner respiration calorimeter to conduct similar experiments on small animals. Together with Charles Ford Langworthy, they compiled a digest of close to 3,600 metabolic experiments as a primer to the research they would conduct.[16] Atwater went on to work with Physicist Edward Bennett Rosa and Nutritionist Francis Gano Benedict to design the first direct calorimeter large enough to accommodate human subjects for a period of days. The calorimeter, or human respiration apparatus, was built to precisely measure the energy provided by food. Atwater wanted to use it to study and compare the nutrient contents of different foods and how the human body consumes those nutrients under various conditions of rest and work.[20] The calorimeter measured human metabolism by analyzing the heat produced by a person performing certain physical activities; in 1896 they began the first of what would accumulate into close to 500 experiments. Through their experiments, they were able to create a system - which became known as the Atwater system, to measure the energy in units, known as food calories.[20] With the machine, the dynamics of metabolism could be quantified and the relationship between food intake and energy output could be measured.[21] "The experiments are made with a man inside a cabinet, or a respiration chamber, as it is called. It is in fact a box of copper incased [sic] in walls of zinc and wood. In this chamber he lives—eats, drinks, works, rests, and sleeps. There is a constant supply of fresh air for ventilation. The temperature is kept at the point most agreeable to the occupant. Within the chamber are a small folding cot-bed, a chair, and a table. In the daytime the bed is folded and laid aside, so as to leave room for the man to sit at the table or to walk to and fro. His promenade, however, is limited, the chamber being 7 feet long, 4 feet wide, and 6 feet high. Food and drink are passed into the chamber through an aperture which serves also for the removal of the solid and liquid excretory products, and the passing in and out of toilet materials, books, and other things required for comfort and convenience."[22] His research was informed by the first law of thermodynamics, taking into account that energy can be transformed but it cannot be created or destroyed, despite the belief at the time that the law only applied to animals because humans were unique. Earlier experiments concerning calorie intake and expenditure had proven that the first law applied to animals and Atwater's findings demonstrated the law applied to humans as well.[20] Through the experiments he demonstrated that whatever amount of energy consumed by humans that could not be used was stored in the body.[20]

Through the calorimetry studies, greater awareness was brought to the food calorie as a unit of measure both for consumption and metabolism. Atwater reported on the weight of the calorie as a means to measure the efficiency of a diet and that different types of food produced different amounts of energy.[20][23] Through his research, he was able to demonstrate that calories from different sources might affect the body differently and in turn, published tables that compared calories in various foods.[23]

Atwater also studied the effect of alcohol on the body. His findings showed humans generated heat from alcohol just as they generated heat from a carbohydrate.[21] At a time when the Scientific Temperance Federation and the Woman's Christian Temperance Union doubted the nutritional value of alcohol, Atwater proved alcohol could be oxidized in the body and used to some extent as fuel. Information gained from Atwater’s experiments was used by the liquor trade in the promotion of alcohol. "[Atwater] was very prominent in the temperance movement, and every year he would lecture the students about temperance and tried to promote [abstention from alcohol]," ... "Being a good scientist, he reported the data and was very upset that alcohol companies used his research" to advertise their products.[20]

Death and legacy

[edit]In 1904, Atwater suffered a stroke and remained unable to work until his death in 1907.[5] He is interred at Indian Hill Cemetery in Middletown, Connecticut.[24]

During his decline, the program at Wesleyan continue through his associates.[8] His collaborator and successor, Frances Benedict continued his work and helped establish a Nutrition Laboratory in Boston with funding from the Carnegie Corporation.[8] Initially, the funding was meant construct a new laboratory for Atwater and fund his continued work; however, with the realization that he would not be returning, the funds were transferred to the Boston laboratory project.[8] Benedict continued Atwater's work and used the respiration calorimeter to further measure metabolism and other bodily processes. Benedict studied the varying metabolism rates of infants born in two hospitals in Massachusetts, athletes, students, vegetarians, Mayans living in the Yucatán, and normal adults.[21] He even developed a calorimeter large enough to hold twelve girl scouts for an extended period of time. His biggest improvement was the invention of portable field respiration calorimeters. In 1919, Francis Benedict published a metabolic standards report with extensive tables based on age, sex, height, and weight.[21]

Atwater's legacy endures not only in the field of nutrition but also in the work of the agricultural experiment stations.[8] Both he and Johnson are considered responsible for focusing the role of the experiment stations on scientific study in service of the public and the tables and formulas Atwater created through his research are still in use today.[8] "His careful studies of nutrition and those that followed helped spur federal policies that have done much to alleviate childhood hunger. We see reflections of his influence on the labels of products in our grocery stores, and we’re beginning to see nutritional information on the menus of restaurants. Today’s familiar food pyramid, a quick and easy visual guide to the recommended daily intake of food, is a tribute to Atwater and his successors."[1] Atwater's daughter, Helen W. Atwater, served as one of his laboratory assistants, namely assisting with manuscript preparation. She served as an editorial assistant in the Office of Experiment Stations from 1898 to 1903; she went on to have a career as a home economics specialist and served as the first full time editor of the Journal of Home Economics.[8][25] His granddaughter, Catherine Merriam Atwater, the daughter of his son, Charles, was an author whom married economist John Kenneth Galbraith.[26]

Atwater's legacy is acknowledged through the yearly W.O. Atwater Memorial Lecture, sponsored through the United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. Each year, a scientist is recognized for their unique contribution toward improving diet and nutrition globally.[27] Atwater and his family's papers are held across multiple institutions, and the collections are, for the most part related to the holding institution.

- Atwater Family Papers, 1778-2003 at Special Collections and Archives, Olin Library, Wesleyan University

- Subset Atwater Family Papers, 1843-1943 at Special Collections and Archives, Wesleyan University

- Wilbur Olin Atwater Papers, 1869-1915 at Special Collections and Archives, Wesleyan University

- Wilbur Olin Atwater Papers at Special Collections of United States Department of Agriculture National Agricultural Library

- Wilbur Olin Atwater papers, 1869-[ca.1914], Collection Number: 2223, Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library

- Wilbur Olin Atwater Papers, circa 1883-1889, Smithsonian Institution Archives

The Wilbur O. Atwater Laboratory at the University of Connecticut is named in his honor. The building houses the Connecticut Veterinary Medical Diagnostic Laboratory.[28]

Bibliography

[edit]- Atwater, W.O. (1894). "Farmers' Bulletin No. 23 - Foods : Nutritive Value and Cost". Internet Archive. Washington, D.C.: United States Department of Agriculture.

- Atwater, W.O. (1910). "Farmers' Bulletin No. 142 - Principles of Nutrition and Nutritive Value of Food". Internet Archive. Washington, D.C.: United States Department of Agriculture.

- Atwater, W.O.; Benedict, F.G. (1993), "An experimental inquiry regarding the nutritive value of alcohol. 1902.", Obesity Research, vol. 1, no. 3 (published May 1993), pp. 228–244, doi:10.1002/j.1550-8528.1993.tb00616.x, hdl:2027/hvd.hwxj1s, PMID 16350575

References

[edit]- ^ a b Olympians Owe Gold Standard to 19th Century Chemist, Fox News. By Paul Martin. Published 31 July 2012. Retrieved 4 August 2012.

- ^ a b c "Wilbur Olin Atwater Papers | Special Collections". specialcollections.nal.usda.gov. Retrieved 2020-04-01.

- ^ a b c d e f "Guide to the Atwater Family Papers, 1788-2003". Special Collections and Archives, Olin Library, Wesleyan University. 2008. Retrieved 1 April 2020.

- ^ Carpenter, KJ (19 April 2001). "Atwater, Wilbur Olin". eLS: 2. doi:10.1038/npg.els.0003423. ISBN 0470016175.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Carpenter, Kenneth J (September 1994). "The Life and Times of W.O. Atwater". The Journal of Nutrition. The 1993 W.O. Atwater Centennial Memorial Lecture. Berkeley, California: Department of Nutritional Sciences, University of California, Berkeley.

- ^ a b c True, A. C. (1908). "Wilbur Olin Atwater. 1844–1907". Proceedings of the Washington Academy of Sciences. 10: 194–198. ISSN 0363-1095. JSTOR 24525334.

- ^ a b c d Nichols, Buford L. (September 1994). "Atwater and USDA Nutrition Research and Service: A Prologue of the Past Century". The Journal of Nutrition. 124 (9 Suppl): 1718S – 1727S. doi:10.1093/jn/124.suppl_9.1718S. PMID 8089739.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Maynard, Leonard A. (September 1962). "Wilbur O. Atwater - A Biographical Sketch (May 3, 1844 - October 6, 1907)". The Journal of Nutrition. 78 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1093/jn/78.1.1. PMID 14471741 – via Oxford Academic.

- ^ a b "Guide to the Wilbur Olin Atwater papers, 1869-[ca.1914]". rmc.library.cornell.edu. Retrieved 2020-04-08.

- ^ Rosenberg, C.E. (1976). No Other Gods: on Science and American Social Thought. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University.

- ^ Osborne, E.A. (1913). From the Letter-Files of S.W. Johnson. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- ^ Atwater, Wilbur O. (1876). "Agricultural-Experiment Stations in Europe". Report of the Commissioner of Agriculture for the Year 1875. United States Government Printing Office: 517–524.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Mudry, Jessica J. (2009-02-18). Measured Meals: Nutrition in America. SUNY Press. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-7914-9386-1.

- ^ Barnes, John M. (1988). "Impacts of the Hatch Act on the Science of Plant Pathology" (PDF). Phytopathology. 78: 36–39.

- ^ "The Hatch Act of 1887 | National Institute of Food and Agriculture". nifa.usda.gov. Retrieved 2020-04-09.

- ^ a b c d Darby, William J. (1994-09-01). "Contributions of Atwater and USDA to Knowledge of Nutrient Requirements". The Journal of Nutrition. 124 (suppl_9): 1733S – 1737S. doi:10.1093/jn/124.suppl_9.1733S. ISSN 0022-3166. PMID 8089741.

- ^ a b Darby, William J. (January 1976). "Nutrition Science: An Overview of American Genius". Nutrition Reviews. 34 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1111/j.1753-4887.1976.tb05660.x. hdl:2027/uiug.30112113103870. PMID 765893.

- ^ Stumbo, Phyllis J. (2015-01-01). "Origins and Evolution of the National Nutrient Databank Conference". Procedia Food Science. The 38th National Nutrient Databank Conference. 4: 13–17. doi:10.1016/j.profoo.2015.06.004. ISSN 2211-601X.

- ^ Atwater, W.O. (1895). Methods and Results of Investigations on the Chemistry and Economy of Food. Washington D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office.

- ^ a b c d e f Hartford Courant, Counting Calories? You Can Thank — Or Blame — Wesleyan Professor, by William Weir, November 23, 2011

- ^ a b c d Lederer, Susan (2007), A History of American Bodies, New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University

- ^ Atwater, W.O. (May–October 1897). "How Food Is Used In The Body - Experiments with men in a respiration apparatus". The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine. 32: 246–252 – via HathiTrust.

- ^ a b Price, Catherine (2018). "Probing the Mysteries of Human Digestion". Distillations. 4 (2). Science History Institute: 26–35. Retrieved November 26, 2018.

- ^ "Wilbur Olin Atwater". www.findagrave.com. Retrieved 12 July 2019.

- ^ The Women's book of world records and achievements. O'Neill, Lois Decker (First ed.). Garden City, New York. February 1979. ISBN 0-385-12732-4. OCLC 4681719.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Lawrence, J. M. "Catherine Galbraith, at 95; transformed economist-husband's life and career", The Boston Globe, October 4, 2008.

- ^ "atwater : USDA ARS". www.ars.usda.gov. Retrieved 2020-04-15.

- ^ "Wilbur O. Atwater Laboratory | Mobile Map | University of Connecticut". maps.uconn.edu. Retrieved 2020-07-23.

Further reading

[edit]- Carpenter, K.J. (1994), "The 1993 W. O. Atwater Centennial Memorial Lecture. The life and times of W. O. Atwater (1844-1907).", The Journal of Nutrition, vol. 124, no. 9 Suppl (published Sep 1994), pp. 1707S – 1714S, doi:10.1093/jn/124.suppl_9.1707S, PMID 8089737

- Combs, G.F. (1994), "Celebration of the past: nutrition at USDA.", The Journal of Nutrition, vol. 124, no. 9 Suppl (published Sep 1994), pp. 1728S – 1732S, doi:10.1093/jn/124.suppl_9.1728S, PMID 8089740

- Darby, W.J. (1976), "Nutrition science: an overview of American genius.", Nutrition Reviews, vol. 34, no. 1 (published Jan 1976), pp. 1–14, doi:10.1111/j.1753-4887.1976.tb05660.x, hdl:2027/uiug.30112113103870, PMID 765893

- Galbraith, C.A. (1994), "Wilbur Olin Atwater.", The Journal of Nutrition, vol. 124, no. 9 Suppl (published Sep 1994), pp. 1715S – 1717S, doi:10.1093/jn/124.suppl_9.1715S, PMID 8089738

Johnson, Rossiter, ed. (1906). "Atwater, Wilbur Olin". The Biographical Dictionary of America. Vol. 1. Boston: American Biographical Society. pp. 161–162.

Johnson, Rossiter, ed. (1906). "Atwater, Wilbur Olin". The Biographical Dictionary of America. Vol. 1. Boston: American Biographical Society. pp. 161–162.{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link)- Pauly, P. J. (1990), "The struggle for ignorance about alcohol: American physiologists, Wilbur Olin Atwater, and the Woman's Christian Temperance Union.", Bulletin of the History of Medicine, vol. 64, no. 3, pp. 366–92, PMID 2261525

- Welsh, S. (1994), "Atwater to the present: evolution of nutrition education.", The Journal of Nutrition, vol. 124, no. 9 Suppl (published Sep 1994), pp. 1799S – 1807S, doi:10.1093/jn/124.suppl_9.1799S, PMID 8089752

- Widdowson, E.M. (1987), "Atwater: a personal tribute from the United Kingdom.", The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, vol. 45, no. 5 (published May 1987), pp. 898–904, doi:10.1093/ajcn/45.5.898, PMID 3554961, S2CID 4452690

- Wilson, P.W. (1963), "Biological Nitrogen Fixation--Early American Style (Samuel W. Johnson and Wilbur O. Atwater)", Bacteriological Reviews, vol. 27, no. 4 (published December 1963), pp. 405–16, doi:10.1128/mmbr.27.4.405-416.1963, PMC 441202, PMID 14097349