Cheddar cheese

| Cheddar cheese | |

|---|---|

| |

| Country of origin | England |

| Region | Somerset |

| Town | Cheddar, Somerset |

| Source of milk | Cow |

| Pasteurised | Depends on variety |

| Texture | Relatively hard |

| Aging time | 3–24 months depending on variety |

| Certification |

|

| Named after | Cheddar |

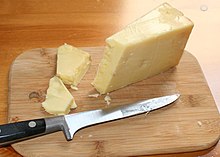

Cheddar cheese (or simply cheddar) is a natural cheese that is relatively hard, off-white (or orange if colourings such as annatto are added), and sometimes sharp-tasting. It originates from the English village of Cheddar in Somerset, South West England.[1]

Cheddar is produced all over the world, and cheddar cheese has no Protected Designation of Origin (PDO). In 2007, the name West Country Farmhouse Cheddar was registered in the European Union and (after Brexit) the United Kingdom, defined as cheddar produced from local milk within Somerset, Dorset, Devon and Cornwall and manufactured using traditional methods.[2][3] Protected Geographical Indication (PGI) was registered for Orkney Scottish Island Cheddar in 2013 in the EU,[4] which also applies under UK law.

Globally, the style and quality of cheeses labelled as cheddar varies greatly, with some processed cheeses packaged as "cheddar". Cheeses similar to Red Leicester are sometimes marketed as "red cheddar".

Cheddar is the most popular cheese in the UK, accounting for 51% of the country's £1.9 billion annual cheese market.[5] It is the second-most popular cheese in the United States behind mozzarella, with an average annual consumption of 10 lb (4.5 kg) per capita.[6] The United States produced approximately 3,000,000,000 lb (1,300,000 long tons; 1,400,000 tonnes) of cheddar in 2014,[7] and the UK produced 258,000 long tons (262,000 tonnes) in 2008.[8]

History

Cheddar cheese originates from the village of Cheddar in Somerset, southwest England. Cheddar Gorge on the edge of the village contains a number of caves, which provided the ideal humidity and steady temperature for maturing the cheese.[8] Cheddar traditionally had to be made within 30 mi (48 km) of Wells Cathedral.[1]

The 19th-century Somerset dairyman Joseph Harding was central to the modernisation and standardisation of cheddar.[9] For his technical innovations, promotion of dairy hygiene, and volunteer dissemination of modern cheese-making techniques, Harding has been dubbed "the father of cheddar".[10] Harding introduced new equipment to the process of cheese-making, including his "revolving breaker" for curd cutting; the revolving breaker saved much manual effort in the cheese-making process.[11][12] The "Joseph Harding method" was the first modern system for cheddar production based upon scientific principles. Harding stated that cheddar cheese is "not made in the field, nor in the byre, nor even in the cow, it is made in the dairy".[9] Together, Joseph Harding and his wife introduced cheddar in Scotland and North America, while his sons Henry and William Harding were responsible for introducing cheddar cheese production to Australia[13] and facilitating the establishment of the cheese industry in New Zealand, respectively.

During the Second World War and for nearly a decade thereafter, most of the milk in Britain was used to make a single kind of cheese nicknamed "government cheddar" as part of the war economy and rationing.[14] As a result, almost all other cheese production in the country was wiped out. Before the First World War, more than 3,500 cheese producers were in Britain; fewer than 100 remained after the Second World War.[15]

According to a United States Department of Agriculture researcher, cheddar is the world's most popular cheese and is the most studied type of cheese in scientific publications.[16]

Process

During the manufacture of cheddar, the curds and whey are separated using rennet, an enzyme complex normally produced from the stomachs of newborn calves, while in vegetarian or kosher cheeses, bacterial, yeast or mould-derived chymosin is used.[17][18]

"Cheddaring" refers to an additional step in the production of cheddar cheese where, after heating, the curd is kneaded with salt, cut into cubes to drain the whey, and then stacked and turned.[17] Strong, extra-mature cheddar, sometimes called vintage, needs to be matured for 15 months or more. The cheese is kept at a constant temperature, often requiring special facilities. As with other hard cheese varieties produced worldwide, caves provide an ideal environment for maturing cheese; still, today, some cheddar is matured in the caves at Wookey Hole and Cheddar Gorge. Additionally, some versions of cheddar are smoked.[19][20]

Character

The ideal quality of the original Somerset cheddar was described by Joseph Harding in 1864 as "close and firm in texture, yet mellow in character or quality; it is rich with a tendency to melt in the mouth, the flavour full and fine, approaching to that of a hazelnut".[21]

Cheddar made in the classical way tends to have a sharp, pungent flavour, often slightly earthy. The "sharpness" of cheddar is associated with the levels of bitter peptides in the cheese. This bitterness has been found to be significant to the overall perception of the aged cheddar flavour.[22] The texture is firm, with farmhouse traditional cheddar being slightly crumbly; it should also, if mature, contain large cheese crystals consisting of calcium lactate – often precipitated when matured for times longer than six months.[23]

Cheddar can be a deep to pale yellow (off-white) colour, or a yellow-orange colour when certain plant extracts are added, such as beet juice. One commonly used spice is annatto, extracted from seeds of the tropical achiote tree. Originally added to simulate the colour of high-quality milk from grass-fed Jersey and Guernsey cows,[24] annatto may also impart a sweet, nutty flavour. The largest producer of cheddar cheese in the United States, Kraft, uses a combination of annatto and oleoresin paprika, an extract of the lipophilic (oily) portion of paprika.[25]

Cheddar was sometimes (and still can be found) packaged in black wax, but was more commonly packaged in larded cloth, which was impermeable to contaminants, but still allowed the cheese to "breathe".[26]

Original-cheddar designation

The Slow Food Movement has created a cheddar presidium,[27] arguing that only three cheeses should be called "original cheddar". Their specifications, which go further than the "West Country Farmhouse Cheddar" PDO, require that cheddar be made in Somerset and with traditional methods, such as using raw milk, traditional animal rennet, and a cloth wrapping.[28]

International production

The "cheddar cheese" name is used internationally; its name does not have a protected designation of origin, but the use of the name "West Country Farmhouse Cheddar" does. In addition to the United Kingdom, cheddar is also made in Australia, Argentina, Belgium, Canada, Germany, Ireland, the Netherlands, New Zealand, South Africa, Sweden, Finland, Uruguay and the United States. Cheddars can be either industrial or artisan cheeses. The flavour, colour, and quality of industrial cheese varies significantly, and food packaging will usually indicate a strength, such as mild, medium, strong, tasty, sharp, extra sharp, mature, old, or vintage; this may indicate the maturation period, or food additives used to enhance the flavour. Artisan varieties develop strong and diverse flavours over time.[citation needed]

Australia

As of 2013, cheddar accounts for over 55% of the Australian cheese market, with average annual consumption around 7.5 kg (17 lb) per person.[29] Cheddar is so commonly found that the name is rarely used: instead, cheddar is sold by strength alone as e.g. "mild", "tasty" or "sharp".[30]

Canada

Following a wheat midge outbreak in Canada in the mid-19th century, farmers in Ontario began to convert to dairy farming in large numbers, and cheddar cheese became their main exportable product, even being exported to England. By the turn of the 20th century, 1,242 cheddar factories were in Ontario, and cheddar had become Canada's second-largest export after timber.[31] Cheddar exports totalled 234,000,000 lb (106,000,000 kg) in 1904, but by 2012, Canada was a net importer of cheese. James L. Kraft grew up on a dairy farm in Ontario, before moving to Chicago. According to the writer Sarah Champman, "Although we cannot wholly lay the decline of cheese craft in Canada at the feet of James Lewis Kraft, it did correspond with the rise of Kraft’s processed cheese empire."[31] Most Canadian cheddar is produced in the provinces of Québec (40.8%) and Ontario (36%),[32] though other provinces produce some and some smaller artisanal producers exist. The annual production is 120,000 tons.[33] It is aged a minimum of three months, but much of it is held for much longer, up to 10 years.[citation needed]

Canadian cheddar cheese soup is a featured dish at the Canada Pavilion at Epcot in Walt Disney World.[34]

Percentage of butterfat or milk fat must be labelled by the words milk fat or abbreviations B.F. or M.F.[35]

New Zealand

Most of the cheddar produced in New Zealand is factory-made, although some are handmade by artisan cheesemakers. Factory-made cheddar is generally sold relatively young within New Zealand, but the Anchor dairy company ships New Zealand cheddars to the UK, where the blocks mature for another year or so.[36]

United Kingdom

Only one producer of the cheese is now based in the village of Cheddar, the Cheddar Gorge Cheese Co.[37] The name "cheddar" is not protected under European Union or UK law, though the name "West Country Farmhouse Cheddar" has an EU and (following Brexit) a UK protected designation of origin (PDO) registration, and may only be produced in Somerset, Devon, Dorset and Cornwall, using milk sourced from those counties.[38] Cheddar is usually sold as mild, medium, mature, extra mature or vintage. Cheddar produced in Orkney is registered as an EU protected geographical indication under the name "Orkney Scottish Island Cheddar".[39] This protection highlights the use of traditional methods, passed down through generations since 1946 and its uniqueness in comparison to other cheddar cheeses.[40] "West Country Farmhouse Cheddar" is protected outside the UK and the EU as a Geographical Indication also in China, Georgia, Iceland, Japan, Moldova, Montenegro, Norway, Serbia, Switzerland and Ukraine.[41]

Furthermore, a Protected Geographical Indication (PGI) was registered for Orkney Scottish Island Cheddar in 2013 in the EU,[4] which also applies under UK law. It is protected as a geographical indication in Iceland, Montenegro, Norway and Serbia.[41]

United States

The state of Wisconsin produces the most cheddar cheese in the United States; other centres of production include California, Idaho, New York, Vermont, Oregon, Texas, and Oklahoma. It is sold in several varieties, namely mild, medium, sharp, extra sharp, New York style, white, and Vermont. New York–style cheddar is particularly sharp/acidic, but tends to be somewhat softer than the milder-tasting varieties. Cheddar that does not contain annatto is frequently labelled "white cheddar" or "Vermont cheddar", regardless of whether it was actually produced there.[citation needed] Vermont's three creameries produce cheddar cheeses – Cabot Creamery, which produces the 16-month-old "Private Stock Cheddar"; the Grafton Village Cheese Company; and Shelburne Farms.[36]

Some processed cheeses or "cheese foods" are called "cheddar flavored". Examples include Easy Cheese, a cheese-food packaged in a pressurised spray can; also, as packs of square, sliced, individually-wrapped "process cheese", which is sometimes also pasteurised.[42]

Cheddar is one of several products used by the United States Department of Agriculture to track the status of America's overall dairy industry; reports are issued weekly detailing prices and production quantities.[43]

Records

U.S. President Andrew Jackson once held an open house party at the White House at which he served a 1,400 lb (640 kg) block of cheddar. The White House is said to have smelled of cheese for weeks.[44]

A cheese of 7,000 lb (3,200 kg) was produced in Ingersoll, Ontario, in 1866 and exhibited in New York and Britain; it was described in the poem "Ode on the Mammoth Cheese Weighing over 7,000 Pounds"[45] by Canadian poet James McIntyre.[46]

In 1893, farmers from the town of Perth, Ontario, produced the "mammoth cheese", which weighed 22,000 lb (10,000 kg) for the Chicago World's Fair.[47] It was to be exhibited at the Canadian display, but the mammoth cheese fell through the floor and was placed on a reinforced concrete floor in the Agricultural Building. It received the most journalistic attention at the fair and was awarded the bronze medal.[48] A larger, Wisconsin cheese of 34,591 lb (15,690 kg) was made for the 1964 New York World's Fair. A cheese this size would use the equivalent of the daily milk production of 16,000 cows.[49]

Oregon members of the Federation of American Cheese-makers created the largest cheddar in 1989. The cheese weighed 56,850 lb (25,790 kg).[50][better source needed]

In 2012, Wisconsin cheese shop owner Edward Zahn discovered and sold a batch of unintentionally aged cheddar up to 40 years old, possibly "the oldest collection of cheese ever assembled and sold to the public". The old cheese has extensive crystallization on the outside and is "creamier and overwhelmingly sharp" on the inside.[51]

See also

- List of cheeses

- Colby, Red Leicester – cheeses similar to cheddar that also contain annatto for a sweet and nutty flavor and an orange colour

- Wedginald – a round of cheddar made famous when its maturation was broadcast on the Internet

References

- ^ a b Smale, Will (21 August 2006). "Separating the curds from the whey". BBC Radio 4 Open Country. Retrieved 7 August 2007.

- ^ "West Country Farmhouse Cheddar”, gov.uk.

- ^ Brown, Steve; Blackmon, Kate; and Cousins, Paul. Operations management: policy, practice and performance improvement. Butterworth-Heinemann, 2001, pp. 265–266.

- ^ a b "Orkney Scottish Island Cheddar". European Union. Retrieved 2 October 2021.

- ^ "The Interview – Lactalis McLelland's 'Seriously': driving the Cheddar market". The Grocery Trader. Retrieved 9 May 2007.

- ^ "Cheese Sales and Trends". International Dairy Foods Association. Archived from the original on 19 May 2011. Retrieved 9 November 2010.

- ^ "Quantity of cheddar cheese produced in the U.S. from 2004 to 2013 (in 1,000 pounds)". Statista. Retrieved 19 December 2015.

- ^ a b Rajan, Amol (22 September 2009). "The Big Question: If Cheddar cheese is British, why is so much of it coming from abroad?". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 9 November 2010.

- ^ a b "Encyclopedia – Harding, Joseph". Gourmet Britain. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 23 June 2009.

- ^ Heeley, Anne; Mary Vidal (1996). Joseph Harding, Cheddar Cheese-Maker. Glastonbury: Friends of the Abbey Barn.

- ^ Transactions of the Royal Highland and Agricultural Society of Scotland, Royal Highland and Agricultural Society of Scotland, 1866-7 volume 1, Aberdeen

- ^ Christabel Susan Lowry Orwin, Edith Holt Whetham, "History of British Agriculture, 1846–1914", Agriculture (1964), page 145

- ^ Blundel, Richard; Tregear, Angela (17 October 2006). From Artisans to "Factories": The Interpenetration of Craft and Industry in English Cheese-Making 1650–1950. Enterprise and Society.

- ^ "Government Cheddar Cheese". Practically Edible. Retrieved 30 April 2011.

- ^ Potter, Mich (9 October 2007). "Cool Britannia rules the whey". Toronto Star. Retrieved 4 January 2009.

- ^ Tunick, Michael H. (23 February 2014). "The biggest cheese? Cheddar". The Boston Globe. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- ^ a b Mount, Harry (18 June 2005). "Savvy shopper: Cheddar". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 10 March 2008.[dead link]

- ^ "Information Sheet – Cheese & Rennet". Vegetarian Society. Archived from the original on 27 March 2008. Retrieved 10 March 2008.

- ^ Wolf, Clark (9 December 2008). American Cheeses. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9780684870021.

- ^ Kelly Jaggers, Moufflet: More Than 100 Gourmet Muffin Recipes That Rise to Any Occasion, p. 104.

- ^ Transactions of the New-York State Agricultural Society for the Year 1864, page 232, volume 14 1865, Albany

- ^ Karametsi, K. (13 August 2014). "Identification of bitter peptides in aged cheddar cheese". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 62 (32): 8034–41. doi:10.1021/jf5020654. PMID 25075877.

- ^ Phadungath, Chanokphat (2011). The Efficacy of Sodium Gluconate as a Calcium Lactate Crystal Inhibitor in Cheddar Cheese (Thesis). University of Minnesota. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- ^ Aubrey, Allison (7 November 2013). "How 17th Century Fraud Gave Rise To Bright Orange Cheese". The Salt. NPR.

- ^ Feldman, David (1989). When Do Fish Sleep? And Other Imponderables of Everyday Life. Harper & Row, Publishers, Inc. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-06-016161-3.

- ^ "The History of Cheese Packaging". www.rocketindustrial.com. Retrieved 8 September 2021.

- ^ Blulab sas. "La Fondazione – slow food per la biodiversità – ONLUS". Slowfoodfoundation.org. Archived from the original on 15 May 2006. Retrieved 23 June 2009.

- ^ "Presidia Artisan Somerset Cheddar". The Slow Food Foundation. Archived from the original on 25 August 2007. Retrieved 9 May 2007.

- ^ "Australian Dairy Industry" Archived 2 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine. dairyaustralia.com.

- ^ "Natural". Archived from the original on 6 May 2017. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- ^ a b "Manufacturing Taste". thewalrus.ca. 12 September 2012.

- ^ "Dairy Products". cdc-ccl.gc.ca. January 2015. Archived from the original on 6 February 2020. Retrieved 12 November 2018.

- ^ "Types of Cheddar cheese, Canadian Living". CanadianLiving.com. Archived from the original on 1 May 2016.

- ^ "Recipe for Canadian Cheddar cheese soup at Epcot".

- ^ Branch, Legislative Services (3 June 2019). "Consolidated federal laws of canada, Food and Drug Regulations". laws.justice.gc.ca. Retrieved 15 July 2019.

- ^ a b Ridgway, Judy. The Cheese Companion. Running Press, 2004, p. 77.

- ^ "Cheddar Gorge Cheese Company". Archived from the original on 29 November 2016. Retrieved 26 September 2006.

- ^ "EU Protected Food Names Scheme – UK registered names". Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. Archived from the original on 31 July 2009. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- ^ "entering a name in the register of protected designations of origin and protected geographical indications (Orkney Scottish Island Cheddar (PGI))". Official Journal of the European Union. Retrieved 19 March 2014.

- ^ "Discover the Best Scottish Cheeses". The Plate Unknown. 3 October 2020. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- ^ a b "GIs worldwide compilation". Origin GI. 3 September 2021.

- ^ "What's Inside: Squirt-On Cheese". Wired.

- ^ "Dairy Mandatory Market Reporting | Agricultural Marketing Service". www.ams.usda.gov. Retrieved 8 April 2021.

- ^ "Andrew Jackson". The Presidents of the United States of America. The White House. Archived from the original on 14 May 2011. Retrieved 24 October 2008.

- ^ Wikisource:Ode on the Mammoth Cheese Weighing over 7,000 Pounds

- ^ "McIntyre, James". University of Toronto Libraries. Retrieved 15 January 2013.

- ^ "Lanark County Genealogical Society -- The Mammoth Cheese". lcgsresourcelibrary.com. Archived from the original on 27 October 2020. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ^ McNichol, Susan. "The Story of the Mammoth Cheese". Archives of the Perth Museum. Archived from the original on 20 October 2020. Retrieved 15 January 2013.

- ^ "Mullins Wisconsin Cheese". Mullins Cheese. Archived from the original on 6 December 2020. Retrieved 15 January 2013.

- ^ "Cheddar Cheese and Cider Farms". Gorges to visit. Archived from the original on 16 February 2013. Retrieved 15 January 2013.

- ^ The Associated Press (31 August 2012). "40-year-old cheese being sold in Wisconsin". oregonlive.

External links

- Icons of England – Cheddar Cheese (non-commercial site commissioned by UK Government Department for Culture, Media and Sport)