White Zimbabweans

| |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| 64,261 (2002)[2] | |

| 12,086 (2006)[note 1] | |

| 5,614 (2020) | |

| Languages | |

| English (majority), Afrikaans, Greek, Portuguese, others (minority)[citation needed] | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Christianity[citation needed] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| White South Africans, White Namibians, Afrikaners, Coloureds, other White Africans, Jews in Africa | |

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1891 | 1,500 | — |

| 1895 | 5,000 | +233.3% |

| 1900 | 12,000 | +140.0% |

| 1904 | 12,596 | +5.0% |

| 1911 | 23,606 | +87.4% |

| 1914 | 28,000 | +18.6% |

| 1920 | 32,620 | +16.5% |

| 1924 | 39,174 | +20.1% |

| 1930 | 47,910 | +22.3% |

| 1935 | 55,419 | +15.7% |

| 1940 | 65,000 | +17.3% |

| 1945 | 82,000 | +26.2% |

| 1950 | 125,000 | +52.4% |

| 1953 | 157,000 | +25.6% |

| 1960 | 218,000 | +38.9% |

| 1965 | 208,000 | −4.6% |

| 1970 | 237,000 | +13.9% |

| 1975 | 300,000 | +26.6% |

| 1979 | 242,000 | −19.3% |

| 1985 | 100,000 | −58.7% |

| 1990 | 80,000 | −20.0% |

| 1995 | 70,000 | −12.5% |

| 2002 | 46,743 | −33.2% |

| 2012 | 28,732 | −38.5% |

| 2017 | 16,998 | −40.8% |

| 2022 | 24,888[4] | +46.4% |

White Zimbabweans, also known as White Rhodesians or simply Rhodesians, are a Southern African people of European descent. In linguistic, cultural, and historical terms, these people of European ethnic origin are mostly English-speaking descendants of British settlers. A small minority are either Afrikaans-speaking descendants of Afrikaners from South Africa or those descended from Greek, Portuguese, Italian, and Jewish immigrants.[2]

In a 1922 referendum, the community rejected joining the Union of South Africa, electing instead to establish responsible government. In the 1964 Rhodesian independence referendum, the community voted overwhelmingly in favour of independence from Britain, leading to Rhodesia's Unilateral Declaration of Independence under Prime Minister, Ian Smith. The community was embroiled in the Rhodesian Bush War (1964-1979), as the Smith government sought to maintain white minority rule. White men were conscripted into the Rhodesian Security Forces and the British South Africa Police. White civilians were targeted in some attacks such as Air Rhodesia Flight 825 and Air Rhodesia Flight 827.[5][6][7] The community faced fresh economic challenges during the UDI period as Britain imposed economic sanctions and Mozambique closed its border in 1976, blocking Rhodesia's access to the Indian Ocean and world commerce.[8][9] Rhodesia was excluded from major sporting events, meaning that its white athletes were unable to participate in the 1968, 1972 and 1976 Olympic Games.[10][11][12]

A small number of British migrants had reached the British colony of Southern Rhodesia, later Zimbabwe, as settlers during the late-nineteenth century. A steady migration of European peoples continued for the next 75 years. The white population of Southern Rhodesia, or Rhodesia as it was known from 1965, reached a peak of about 300,000 in 1975–76, representing around 8% of the population.[13]

Emigration after the country gained internationally recognised independence as Zimbabwe in 1980 resulted in a declining white population: estimated at 220,000 in 1980; 70,000 in 2000;[14] and 30,000 in 2012.[15][16] However, by 2023, the white population had increased following the government easing restrictions regarding white ownership of farmland. Many formerly dispossessed white farmers have formed joint ventures with black landowners.[17] There are currently three ministers in the Zimbabwean Government who are white, Kirsty Coventry, Joshua Sacco and Vangelis Haritatos, while in 2023, David Coltart was elected as Mayor of Bulawayo, becoming the first white mayor since 1981.

Background

[edit]Present-day Zimbabwe (known as Southern Rhodesia from 1895) was occupied by the British South Africa Company (BSAC) from the 1890s onward, following its subjugation of the Matabele (Ndebele) and Shona nations. Early White settlers came in search of mineral resources, hoping to find a second gold-rich Witwatersrand. Zimbabwe lies on a plateau that varies in altitude between 900 and 1,500 m (2,950 and 4,900 ft) above sea level. This gives the area a moderate climate which was conducive to European settlement and commercial agriculture.[18]

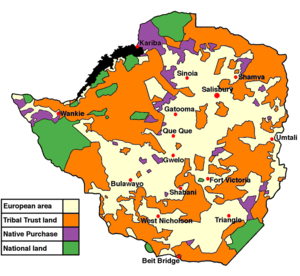

White settlers who assisted in the BSAC takeover of the country were given land grants of 1,200 hectares (3,000 acres); the black people who had long lived on the land were classified legally as tenants.[19][20] In 1930, Land Apportionment and Tenure Acts displaced Africans from the country's best farmland, restricting them to unproductive and low-rainfall tribal-trust lands. It reserved areas of high rainfall for White ownership.[21] White settlers were attracted to Rhodesia by the availability of tracts of prime farmland that could be purchased from the state at low cost. This resulted in the growth of commercial agriculture in the young colony. The White farm was typically a large (>100 km2 (>38.6 mi2)) mechanized estate, owned by a White family and employing hundreds of Black people. Many White farms provided housing, schools and clinics for Black employees and their families.[22] At the time of independence in 1980, more than 40% of the country's farmed land was made up of approximately 5,000 White farms.[23] At the time, agriculture provided 40% of the country's GDP and up to 60% of its foreign earnings.[24] Major export products included tobacco, beef, sugar, cotton and maize. The minerals sector was also important. Gold, asbestos, nickel and chromium were mined by foreign-owned concerns such as Lonrho (Lonmin since 1999) and Anglo American.

The Census of 3 May 1921 found that Southern Rhodesia had a total population of 899,187, of whom 33,620 were Europeans; 1,998 were Coloured (mixed race); 1,250 Asiatics; 761,790 Bantu natives of Southern Rhodesia; and 100,529 Bantu aliens.[25] The following year, Southern Rhodesians rejected, in a referendum, the option of becoming a province of the Union of South Africa. Instead, the country became a self-governing British colony. It never gained full dominion status, but unlike other colonies, it was treated as a de facto dominion, with its Prime Minister attending the Commonwealth Prime Ministers' Conferences.

History

[edit]Portuguese explorer António Fernandes was the first European to visit the region.[26]

Settlement

[edit]In 1891, before Southern Rhodesia was established as a territory, it was estimated that about 1,500 Europeans resided there. This number grew slowly to around 75,000 in 1945. In the period 1945 to 1955, the white population doubled to 150,000, and during that decade 100,000 black people were forcibly resettled from farmland designated for white ownership.[27] However, some members of the white farming community opposed the forced removal of black people from land designated for white ownership. Some favoured the transfer of underutilised "white land" to black farmers. For example, in 1947, Wedza white farmer Harry Meade unsuccessfully opposed the eviction of his black neighbour Solomon Ndawa from a 200-hectare (500-acre) irrigated wheat farm. Meade represented Ndawa at hearings of the Land Commission and attempted to protect Ndawa from abusive questioning.[28]

Large-scale migration to Rhodesia did not begin until after the Second World War. At the colony's first comprehensive census in 1962, Rhodesia had 221,000 white residents. At its peak in the mid-1970s, Rhodesia's white population consisted of as many as 277,000.[29] There were influxes of white immigrants from the 1940s through to the early 1970s. The country saw a net gain of 9,400 white immigrants in 1971, the highest number since 1957 and the third highest on record.[30] In the immediate postwar period, the most conspicuous group were former British servicemen. However, many of the new immigrants were refugees from Communism in Europe; others were former service personnel from British India, or came from the former Kenya Colony, the Belgian Congo, Zambia, Algeria, and Mozambique. For a time, Rhodesia provided something of a haven for white people who were retreating from decolonisation elsewhere in Africa and Asia.[31] In 1974 the Smith government launched a massive campaign to attract one million Europeans to settle in the country.[32]

Post-World War II Rhodesian white settlers were considered different in character from earlier Rhodesian settlers and those from other British colonies. In Kenya, settlers were perceived to be drawn from "the officer class" and from the British landowning class. By contrast, settlers in Rhodesia after the Second World War were perceived as being drawn from lower social strata and were treated accordingly by the British authorities. As Peter Godwin wrote in The Guardian, "Foreign Office mandarins dismissed Rhodesians as lower middle class, no more than provincial clerks and artisans, the lowly NCOs of empire."[33]

Various factors encouraged the growth of the white population of Rhodesia. These included the industrialisation and prosperity of the economy in the post-war period. The National Party victory in South Africa was one of the factors that led to the formation of the Central African Federation (1953-1963), so as to provide a bulwark against Afrikaner nationalism. British settlement and investment boomed during the Federation years, as Southern Rhodesia, Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia), and Nyasaland (now Malawi) formed a powerful economic unit, counterbalancing the economic power of South Africa. The economic power of these three areas was a major factor in the establishment of the Federation through a British Act of Parliament. It was also apparent as early as the 1950s that white rule would continue for longer in Rhodesia than it would in other British colonies such as Zambia (Northern Rhodesia) and Kenya. Many of the new immigrants had a "not here" attitude to majority rule and independence.[34]

Rhodesia was run by a white minority government. In 1965, that government declared itself independent through a Unilateral Declaration of Independence ('UDI') under Prime Minister Ian Smith.[35] The UDI project eventually failed, after a period of United Nations economic sanctions and a civil war known as the Chimurenga (Shona) or Bush War. British colonial rule returned in December 1979, when the country became the British Dependency of Southern Rhodesia. In April 1980, it was granted independence as Zimbabwe.

The Rhodesian community kept itself largely separate from the black and Asian communities in the country.[36] Urban Rhodesians lived in separate areas of town, and had their own segregated education, healthcare and recreational facilities. Marriage between Zimbabweans and Rhodesians was possible, but remains to the present day very rare. The 1903 Immorality Suppression Ordinance made "illicit" (i.e. unmarried) sex between black men and white women illegal – with a penalty of two years imprisonment for any offending white woman.[37] The majority of the early white immigrants were men, and some white men entered into relationships with black women. The result was a small number of mixed-race persons: 1,998 out of a total 899,187 inhabitants, according to the 1921 census, some of whom were accepted as being white. A proposal by Garfield Todd (Prime Minister in 1953–1958) to liberalise the laws regarding interracial sex was viewed as dangerously radical. The proposal was rejected and was one factor that led to the political demise of Todd.[38]

Rhodesians enjoyed a very high standard of living. The Land Tenure Act had reserved 30% of agricultural land for white ownership. Black labour costs were low (around US$40 per month in 1975) and included free housing, food and clothing. Nurses earned US$120 per month. The low wages had a large effect in the context of an agricultural economy.[39] Public spending on education, healthcare and other social services was heavily weighted towards white people. Most of the better paid jobs in public service were also reserved for white people.[40] White people in skilled manual occupations enjoyed employment protection against black competition.[41] In 1975, the average annual income for a Rhodesian was around US$8,000 (equivalent to $45,000 in 2023) with income tax at a marginal rate of 5% — making them one of the richest communities in the world.[39]

Decline

[edit]In November 1965, in order to avoid the introduction of black majority rule (commonly referred to at the time as the Wind of Change), the Government of what was then the self-governing colony of Southern Rhodesia issued the Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI), upon which the country became the de facto independent – albeit unrecognised — state of Rhodesia.

As was the case in most European colonies, white immigrants took a privileged position in all areas of society. Extensive areas of prime farmland were owned by whites. Senior positions in the public services were reserved for whites, and whites working in manual occupations enjoyed legal protection against job competition from black Africans. As time passed, this situation became increasingly unwelcome to the majority ethnic groups within the country and also to wide sections of international opinion, leading to the Rhodesian Bush War and eventually the Lancaster House Agreement in 1979.

After the country's reconstitution as the Republic of Zimbabwe in 1980, Rhodesians had to adjust to being an ethnic minority in a country with a black majority government. Although a significant number of Rhodesians remained, many of them emigrated in the early-1980s, both in fear for their lives and an uncertain future. Political unrest and the seizure of many white-owned commercial farms resulted in a further exodus of Rhodesians commencing in 1999. The 2002 census recorded 46,743 Rhodesians living in Zimbabwe. More than 10,000 were elderly and fewer than 9,000 were under the age of 15.[42]

At the time of Zimbabwean independence in 1980, it was estimated that around 38% of Rhodesians were UK-born, with slightly fewer born in Rhodesia, and around 20% from elsewhere in Africa.[43] The white population of that era contained a large transient element, and many white people might better be considered foreign migrants than settlers. Between 1960 and 1979, white emigration to Rhodesia was around 180,000, while white emigration overseas was 202,000 (with an average white population of around 240,000).[44] White emigration accelerated as independence approached. In October 1978 the net white emigration of 1,582 was the highest recorded number of departures since Rhodesia declared its UDI in 1965. According to official government statistics, 1,834 whites emigrated and 252 white immigrants arrived.[45] In the first nine months of 1978, 11,241 whites emigrated.[46] In an attempt to stem emigration, the Rhodesian government allowed each departing family to only take up to $1,400 out of the country.[47]

Post-independence

[edit]The country gained its independence as Zimbabwe in April 1980, under a ZANU-PF government led by Robert Mugabe. Following independence, the country's white citizens lost most of their former privileges. A generous social welfare net (including both education and healthcare) that had supported white people in Rhodesia disappeared almost in an instant. White people in the artisan, skilled worker and supervisory classes began to experience job competition from black people. Indigenisation in the public services displaced many white people. The result was that white emigration gathered pace. In the ten-year period from 1980 to 1990, approximately two-thirds of the white community left Zimbabwe.[48]

However, many white people resolved to stay in the new Zimbabwe; only one-third of the white farming community left. An even smaller proportion of white urban business owners and members of the professional classes left.[49] This pattern of migration meant that although small in absolute numbers, Zimbabwe's white people formed a high proportion of the upper strata of society.

A 1984 article in The Sunday Times Magazine described and pictured the life of Zimbabwean white people at a time when their number was just about to fall below 100,000.[50] About 49% of emigrants left to settle in South Africa, many of whom were Afrikaans speakers, with 29% going to the British Isles; most of the remainder went to Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and the United States.[51] Many of these emigrants continue to identify themselves as Rhodesian. A white Rhodesian/Zimbabwean who is nostalgic for the UDI era is known colloquially as a "Rhodie".[52] These nostalgic "Rhodesians" are also sometimes referred to by the pejorative "Whenwes", because of the nostalgia expressed by them in the phrase "when we were in Rhodesia".[53]

The 1979 Lancaster House Agreement, which was the basis for independence from the United Kingdom, had precluded compulsory land redistribution in favour of subsidised voluntary sale of land by white owners for a period of at least 10 years. The pattern of land ownership established during the Rhodesian state therefore survived for some time after independence. Those white people who were prepared to adapt to the situation they found themselves in were therefore able to continue enjoying a very comfortable existence. In fact, the independence settlement, combined with favourable economic conditions (including the Economic Structural Adjustment Programme), produced a 20-year period of unprecedented prosperity for white Zimbabwean people, and for the white farming community in particular; a new class of "young white millionaires" appeared in the farming sector.[54] These were typically young Zimbabweans who had applied skills learned in agricultural colleges and business schools in Europe. In 1989, Commercial Farmers' Union president John Brown commented, "This is the best government for commercial farmers that this country has ever seen".[55]

The lifting of UN-imposed economic sanctions and the end of the Bush War at the time of independence produced an immediate 'peace dividend'. Renewed access to world capital markets made it possible to finance major new infrastructure developments in transport and schools. One area of economic growth was tourism, catering in particular to visitors from Europe and North America. Many white people found work in this sector. Another area of growth was horticulture, involving the cultivation of flowers, fruits and vegetables, which were air-freighted to market in Europe. Many white farmers were involved in this, and in 2002 it was claimed that 8% of horticultural imports into Europe were sourced in Zimbabwe.[56] The economic migrant element among the white population had departed quickly after independence, leaving behind those white people with deeper roots in the country. The country settled and the white population stabilised.

Chris McGreal, writing in The Observer in April 2008, claimed that Zimbabwe's white people "... kept their houses and their pools and their servants. The white farmers had it even better. With crop prices soaring they bought boats on Lake Kariba and built air strips on their farms for newly acquired planes. Zimbabwe's whites reached an implicit understanding with Zanu-PF; they could go on as before, so long as they kept out of politics".[57]

White Zimbabweans with professional skills were readily accepted in the new order. For example, Chris Andersen had been the hardline Rhodesian justice minister, but made a new career for himself as an independent MP and leading attorney in Zimbabwe. In 1998, he defended former President Canaan Banana in the infamous "sodomy trial".[58] At the time of this trial, Andersen spoke out against the attitude of President Mugabe who had described homosexuals as being "worse than dogs and pigs since they are a colonial invention, unknown in African tradition."[59]

John Bredenkamp started his trading business during the UDI era, when he developed expertise in "sanctions busting". He is reported to have arranged the export of Rhodesian tobacco and the import of components (including parts and munitions for the Rhodesian government's force of Hunter jets) in the face of UN trade sanctions. Bredenkamp was able to continue and expand his business after independence, making himself a personal fortune estimated at US$1 billion.[60]

Several white Zimbabwean businessmen, such as Billy Rautenbach, have returned to their native country after working abroad for some years. Rautenbach has succeeded in extending Zimbabwean minerals sector activity into neighbouring countries such as the DRC.[61] Charles Davy is one of the largest private landowners in Zimbabwe. Davy is reported to own 1,200 km2 (460 mi2) of land, including farms at Ripple Creek, Driehoek, Dyer's Ranch and Mlelesi. His property has been almost unaffected by any form of land redistribution, and he denies that this fact has any link to his business relationship with the politician Webster Shamu. Davy has said about Shamu, "I am in partnership with a person who I personally like and get along with".[62] Other views on Shamu are less kind.[63]

The political environment in Zimbabwe has allowed the development of an exploitative business culture, in which some white businessmen have played a prominent role.[64][65] When Zimbabwe was subject to EU sanctions, arising from its involvement in the DRC from 1998, the government was able to call on sanctions-busting expertise and personnel from the UDI era to provide parts and munitions for its force of Hawk jets. After 25 years of ZANU-PF government, Zimbabwe had become a congenial place for white millionaires of a certain kind to live and do business in.[66]

The Independence constitution contained a provision requiring the Zimbabwean government to honour pension obligations due to former servants of the Rhodesian state. This obligation included payment in foreign currency to pensioners living outside Zimbabwe (almost all white). Pension payments were made until the 1990s, but they then became erratic and stopped altogether in 2003.[67]

Since the land invasions and chaotic political situation in the country, a number of expatriate white farmers and hoteliers from Zimbabwe have resettled in neighbouring Zambia, where they are reviving agriculture and develop the local tourism industry.[68][69] Since 2009 the British government has put into action a repatriation plan assisting elderly British citizens living in Zimbabwe to resettle in the United Kingdom.[70][71] Challenges for some of Zimbabwe's remaining white community include being reliant on remittances sent by relatives overseas, the cost of private healthcare and cost of living.[72]

The community was the target of a degrading campaign by the Zimbabwean State media in the 2000s. Several state newspapers referred to white Zimbabweans as "Britain's Children" and "settlers and colonialists".[73] In 2006,[74][75] several white Zimbabweans living in the affluent Harare suburb of Borrowdale were evicted from their homes because of their proximity to Mugabe's new home in the area. In 2007,[76] it was reported that 100 mostly white youths were arrested during a raid at Borrowdale's Glow nightclub, before being transported in two police buses and detained in the downtown central police station. According to eyewitnesses, several of the youths were attacked by Zimbabwean police.[77]

Lancaster Deal and Land reform

[edit]The Lancaster house agreement took place from 10 September – 15 December 1979 with 47 plenary sessions formally held in which Lord Carrington, Foreign and Commonwealth Secretary of the United Kingdom, chaired the Conference.[citation needed]

The content of Lancaster House Agreement covered the new constitution, pre-independence arrangements, and the terms of ceasefire along with an agreement of a bilateral payment from the UK to the republic of Zimbabwe in aid to the land reforms. The agreement signed under Margaret Thatcher, sought out to aid the oncoming land redistribution as powers shifted from the known Rhodesia to the now known Zimbabwe.[citation needed]

By the mid-1990s, it is thought that around 120,000 white people remained in Zimbabwe.[78] In spite of this small number, the white Zimbabwean minority maintained control of much of the economy through its investment in commercial farms, industry, and tourism. However, an ongoing programme of land reforms (intended to alter the ethnic balance of land ownership) dislodged many white farmers. The level of violence associated with these reforms in some rural areas made the position of the wider white community uncomfortable. Twenty years after independence, there were 21,000 commercial farmers in the country.

In 1997, the British prime minister Tony Blair and his government pulled out of talks to fund the Lancaster House agreements causing a traction. This would lead to the land grabs that were seen soon after. The war veterans felt as if the inability of the UK government to continue its agreement meant they must take a stand. The land grabs formally followed after, in cause of the crumbling relations with the UK government.[citation needed]

The Fast track land reform came to assume a very high profile in Zimbabwe's political life. ZANU politicians sought to revise Rhodesian land apportionment, which they saw as an injustice and pressed for land to be properly dispersed among white and black ownership. White farmers argued that this served little purpose. Therefore, to their eyes, the problem was really a lack of development, rather than one of land tenure. White farmers would respond to claims that they owned "70% of the best arable land" by stating that what they actually owned was "70% of the best developed arable land", and therefore that the two are entirely different things.[79] Whatever the merits of the arguments, in the post-independence period, the land issue assumed enormous symbolic importance to all concerned. As the euphoria of independence subsided, and as a variety of economic and social problems became evident in the late-1990s, the land issue became a focus for trouble.

This was intention was to equally allocate the 4,000 white farms, covering 110,000 km2 (42,470 mi2) of mostly prime farmland, among the majority. The means used to implement the programme were ad-hoc, and involved forcible seizure in many cases.[80]

By mid-2006, only 500 of the original 5,000 white farms were still fully operational.[81] The majority of the white farms that avoided expropriation were in Manicaland and Midlands, where it proved possible to do local deals and form strategic partnerships. However, by early-2007, a number of the seized farms were being leased back to their former white owners (although in reduced size or on a contract basis); it has been claimed to be possible that as many as 1,000 of them could be operational again, in some form.[82]

A University of Zimbabwe sociologist told IWPR journalist Benedict Unendoro that the esprit de corps of the white dominant class in the former Rhodesia prevented the poor white people from becoming a recognisable social group, because of the social assistance provided by the dominant social class on racial grounds. This system broke down after the founding of Zimbabwe, causing the number of poor white people to increase, especially after 2000, when the confiscation of white-owned farms took its toll. As rich white land owners emigrated or fended for themselves financially, their white employees, who mainly worked as supervisors of black labour, found themselves destitute on the streets of cities like Harare, with many found begging around urban centres like Eastlea. The land confiscated from white owners has been redistributed to black peasant farmers and smallholders, acquired by commercial land companies, or persons connected to the government.[83][84]

Sympathisers of the expropriated white farmers have claimed that lack of professional management skills among the new landholders has resulted in a dramatic decline in Zimbabwe's agricultural production.[85] Indeed, in an effort to boost their own agricultural output, neighbouring countries, including Mozambique and Zambia, offered land and other incentives to entice Zimbabwe's white farmers to emigrate.[86]

By 2008, an estimated one in ten out of 5,000 white farmers remained on their land. Many of these continued to face intimidation, however.[87] By June 2008, it was reported that only 280 white farmers remained, and all of their farms were invaded.[88] On the day of Mugabe's inauguration as president on 28 June 2008, several white farmers who had protested the seizure of their land were beaten and burned by his supporters. In June 2008, a British-born farmer, Ben Freeth (who has had several articles and letters published in the British press regarding the hostile situation), and his in-laws, Mike and Angela Campbell, were abducted and found badly beaten.[89][90][91] Campbell, speaking from hospital in Harare, vowed to continue with his legal fight for his farm.[92] In November 2008, a SADC tribunal ruled that the government had racially discriminated against Campbell, denied him legal redress, and prevented him from defending his farm.[93]

In 2017, new President Emmerson Mnangagwa's inaugural speech promised to pay compensation to the white farmers whose land was seized during the land reform programme.[94] Rob Smart became the first white farmer whose land was returned within a month after President Mnangagwa was sworn in to office; he returned to his farm in Manicaland province by military escort.[95] During the World Economic Forum 2018 in Davos, Mnangagwa also stated that his new government believes thinking about racial lines in farming and land ownership is "outdated", and should be a "philosophy of the past."[96] As of 2023[update], there are 900 white-run commercial farms in the country. The farmers are not usually working their own land, but are renting in joint ventures from black farmers given confiscated white-owned land.[97]

Violence against whites

[edit]Since the 2000s, there has been a surge in violence against Zimbabwe's dwindling white community, with the main targets of this violence being Zimbabwe's white farmers. On 18 September 2010, droves of white people were chased away and prevented from participating in the constitutional outreach programme in Harare during a weekend, in which violence and confusion marred the process, with similar incidents having occurred in Graniteside. In Mount Pleasant, white families were subjected to a torrent of abuse by suspected Zanu-PF supporters, who later drove them away and shouted racial slurs.[98] There were also many illegal seizures of white-owned farmland by the government and its supporters. By March 2000, little land had been redistributed as per the land reform laws that were passed in 1979, when the Lancaster House Agreement between Britain and Zimbabwe pledged to initiate a fairer distribution of land between the white minority, which governed Zimbabwe from 1890 to 1979, and the black population.

However, at this stage, land acquisition could only occur on a voluntary basis. Little land had been redistributed, and frustrated groups of government supporters began seizing white-owned farms. Most of the seizures took place in Nyamandlovu and Inyati.[99] After the beating to death of a prominent farmer in September 2011, the head of the Commercial Farmers' Union decried the attack, saying that its white members continue to be targeted for violence, without protection from the government.[100] Genocide Watch declared that the violence against whites in Zimbabwe was a stage 5 (of 10) case of genocide.[101] In September 2014, Mugabe publicly declared that all white Zimbabweans should "go back to England", and he urged black Zimbabweans not to lease agricultural land to white farmers.[102]

Hundreds of white farmers returned to Zimbabwe following a mellowing of government restrictions on white Zimbabweans owning land, with many of the returning white farmers forming joint ventures with black farm owners.[103]

Communities

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (September 2023) |

Afrikaner

[edit]The first wave of Afrikaners arrived in ox wagons in 1893, brought to the country at the time by the pioneer Duncan Moodie.[104] The Afrikaners that followed mostly settled on farms in the subtropical lowlands of the southeast, and on the high central and northwestern plains known for its cattle ranching. It is estimated that the community peaked in the late 1960s, numbering some 25,000.[104] P. K. van der Byl, an Afrikaner, served as Rhodesia's Minister of Foreign Affairs (1974-1979).[105] Thousands returned to South Africa after independence in Zimbabwe in 1980; however, as many as 15,000 remained four years later in 1984.[104] They were sometimes disparaged by their Anglo-Saxon counterparts in the country, who referred to them as "japies", "hairy-backs", "rock spiders" and "ropes".[106][107] Until the end of the Second World War, "the race problem" in Southern Rhodesia referred exclusively to Afrikaner and English-speaking rivalries.[108] However, Afrikaners in the country did not push for the most radical demands of Afrikaner nationalism, including the absolute rejection of empire.[108] "Anti-Dutch" sentiment contributed to white Rhodesia's rejection of union with South Africa in the 1922 referendum, as well as a fear that union would bring a wave of Afrikaner "poor whites" to the country.[108] Some Afrikaners came to the country to escape the National Party politics, and they looked to Southern Rhodesia, not to become closer to Britain, but to forge a White African identity with English-speaking whites that was free of the Afrikaner supremacy in South Africa.[108]

Jewish

[edit]The earlier wave of Jewish immigration consisted of Ashkenazi Jews from Russia and Lithuania.[109] An active Jewish community with a synagogue has existed in Salisbury (now Harare) since 1894.[110] In the 1930s, a wave of Sephardi Jews arrived from Rhodes, the Greek island. German Jews fleeing persecution in the Third Reich also settled in the country.[109] A number of Jews arrived from the Belgian Congo, escaping the civil war engulfing the newly-independent country.[109] The Jewish community reached a peak of 7,060 to 7, 500 between 1961 and the early 1970s.[109][110] There were three active synagogues in Salisbury (now Harare), one in Bulawayo and a plethora of Jewish community centers, sports clubs, primary schools, youth movements and other organizations, such as the Chevra Kadisha (Jewish burial society). Smaller Jewish communities also existed in Gatooma, Gwelo and Que Que.[110] There are currently two active synagogues in the country, both are in Harare: the Ashkenazi synagogue and the Sephardi synagogue. As congregation numbers have depleted, both communities combine minyanim on Shabbat.[110] Two Jewish primary schools continue to operate, with Sharon School in Harare, and Carmel in Bulawayo. With the local Jewish community decreasing in size, most of the students at the schools are not Jewish, however.[111]

Greek

[edit]The Greek Community in Zimbabwe peaked at between 13,000-15,000 people in 1972, but has decreased significantly to around 1,000 Greeks or people of Greek origin.[112] The Greek Cypriot community in Zimbabwe is slightly larger, with 1,200 Cypriots continuing to live in the country.[112] The Greeks and Cypriots were mostly known for running restaurants and small businesses in the country.[113] There are some significant Greek and Cypriot business owners and landowners, with the majority of the Hellenic community employed in trade professions or involved in bakery operations.[112] Hellenic Academy, an independent Greek high school was established in Harare in 2008 and continues to operate.[112] The Holy Archdiocese of Zimbabwe and Southern Africa is under the jurisdiction of the Patriarchate of Alexandria.[112]

Italian

[edit]Italians came to Zimbabwe as early as 1906, when they formed a settlement named Sinoa in today's Chinhoyi.[114]

Portuguese

[edit]Portuguese migrants came from Portuguese Mozambique to work in the building trade,[113] with later waves coming from newly-independent Angola and Mozambique.[115]

Arts and entertainment

[edit]Several cultural organisations existed during white-minority rule that mainly served the interests of the community. These included The National Gallery, The National Arts Foundation and the Salisbury Arts Council.[116]

Literature

[edit]Fiction

[edit]Artistic expression often portrays "the melancholy white exile" from Zimbabwe who secretly longs to return home.[117]

Gertrude Page's Rhodesia novels were all written between the years 1907 and 1922.[118] These novels included Love in the Wilderness (1907), The Edge O' Beyond (1908) and The Pathway (1914).[118] In The Rhodesian (1914), Page writes admiringly of agricultural productivity and colonial settlement in her "empty" Rhodesian landscapes: "The Valley of Ruins no longer lies alone and unheeded in the sunlight; and no longer do the hills look down upon rich plains left solely to ... idle pleasures."[118] In the novel she imagines Cecil Rhodes as "enslaved and enfolded" by the landscape, an "enchantress who bound men's souls for ever", and wonders whether Rhodesia had been "wife and child" to him, in his solitude, thus implying that Page imagines Rhodes as a husband and father to the nation.[118] Cynthia Stockley, the South African-born novelist, lived in Rhodesia and set several of her novels there such as Virginia of the Rhodesians (1903) and The Claw (1911). As with Page, Stockley's heroes are heavily impacted by the powerful African landscape: "Africa has kissed him on the mouth and he will not leave her."[118] In The Claw, she wrote of the country's empty landscapes that allowed for both personal freedom and expansion of the soul: "The world seemed filled with gracious dimness and made up of illimitable space. An indescribable feeling of happy freedom filled my heart. It seemed to me that the lungs of my soul drew breath and expanded as they had never done in any land before."[118] Although Stockley shows a commitment to Rhodesian patriotism in her novels, her nationalism shifted towards Union with South Africa in Tagati (1930).[118]

Doris Lessing (1919-2013) was awarded the 2007 Nobel Prize in Literature, becoming the second white African woman to win a Nobel prize, after South Africa's Nadine Gordimer in 1991. Her earlier poetry was published in the regular publication, New Rhodesia (1938-1954), which published lively commentary affairs.[119] Her debut novel, The Grass Is Singing (1950), about a relationship between a white woman and a black man, is set in Southern Rhodesia of the late 1940s. The novel begins with a newspaper announcement of a white woman's murder on the veld: "The newspaper did not say much. People all over the country must have glanced at the paragraph with its sensational heading and felt a little spurt of anger mingled with what was almost satisfaction, as if some belief had been confirmed, as if something had happened which could only have been expected. When natives steal, murder or rape, that is the feeling white people have."[120][121]

A number of white writers in the country had their poetry published by the Poetry Society of Rhodesia (founded in 1950). In 1952, the society's journal appeared as the Poetry Review Salisbury, before becoming Rhodesian Poetry.[119][122] The South African writer Alan Paton was a chairman of the society in the 1970s.[123] It appeared sometimes annually and sometimes biennially until independence in 1980.[119] In the 1970s, it published new material as well as well-received poetry that had been published elsewhere in the country in the preceding two years.[119] Many of these poems came from Two Tone, a quarterly publication that aimed to publish both black and white writers. The founders, Phillipa Berlyn and Olive Robertson, were acolytes of the Rhodesia Front.[119] Berlyn held the belief that an independent Rhodesia would need to accommodate both black and white citizens, and her quarterly could be an outlet where poets from different races could listen to one another.[119] Once the Rhodesian Bush War came to the forefront in 1972 and emigration increased, white poets became less confident in expressing their own identity, and more frequently the poems appearing in Two Tone and Rhodesian Poetry were about the experiences of war.[119] John Eppel[124][125] was conscripted repeatedly during the final years of the war and in his poem "Spoils of War", he recalls looking at the bodies of guerrillas killed during a contact:[119]

Sarge tells me to save my tears

for the civilians these gooks have slaughtered.

But I am not thinking of them, and I

cannot explain that I am being purged

of my Rhodesianism. That ugly

word with its jagged edge is opening

me. . . . I move to the past tense.

Colin Style, a contributor to both Two Tone and Rhodesia Poetry, was awarded the Ingrid Jonker Prize for best published collection in English in Southern Africa, 1977 with Baobab Street (1977).[126][127] He wrote with unashamed nostalgia for his native country's veld, its disappearance among new building developments and for Rhodesia itself. In "The Cemetery," the life and culture of a Rhodesia that will become a memory are presented as detached from the present as a San rock painting:[119]

The soil is fine:

it mingles with my sweat and stains red in my sandal,

muddy itching ochre seeping into mind

while in their crevices and caves the rock-imprinted impala

restlessly stir.

N. H. Brettell was also a significant white poet in the country since publishing Bronze Frieze: Poems Mostly Rhodesian (1950). In a 1978 academic essay on Rhodesian poetry, Graham Robin wrote that "Brettell puts into words the halting stupefaction of the exile in such a new and strange land. At last Rhodesia has a poet possessed by his country; but amazed, almost reluctantly possessed."[122] Brettell also befriended the poet, short story writer and Anglican priest, Arthur Shearly Cripps. Cripps was critical of the British South Africa Company and settler rule.[119] He was the most widely represented writer in Rhodesian Verse, 1888–1938, the first anthology of Rhodesian poetry (edited by John Snelling).[119] In the post-war period and in his final years, Cripps published poetry in Labour Front, which provided a platform for white radicalism.[119] Left-leaning white writers also wrote for the Central African Examiner (1957-1965), where writers engaged with race, statehood and universal suffrage. The poetry was often satiric, subverting the political ideology and claims of the federal and Southern Rhodesian establishment.[119] The publication ceased publication in 1965 due to the censorship laws put in place in the wake of Rhodesia's Unilateral Declaration of Independence.[119] Hundreds of mostly partisan novels were also published in the UDI era of the 1960s and 1970s by white writers in the country supporting the Smith government.[128]

In the final years of UDI Rhodesia, Rhodesian poetry that encompassed the work of both black and white writers was seen as inappropriate by many black writers.[119] In 1978, Kizito Muchemwa edited Zimbabwean Poetry in English: An Anthology, a collection that only contained the work of black writers.[119] The use of Zimbabwean rather than Rhodesian as a term of identity was regarded as subversive at the time.[119]

Lauren Liebenberg centred her debut novel, The Voluptuous Delights of Peanut Butter and Jam, on a Rhodesian farm in 1978. It was nominated for the Orange Prize for Fiction in 2008. Liebenberg drew upon some of her own experiences as a child growing up in war-torn Rhodesia.[129] Alexander McCall Smith, who was born and brought up in Southern Rhodesia, has also enjoyed notable success. In particular, he is known as the creator of the Africa-inspired series The No. 1 Ladies' Detective Agency, set in neighbouring Botswana.[130]

Non-fiction

[edit]

Uncritical accounts of white-minority rule in the country formed part of the teaching syllabi recommended by the Rhodesian Ministry of Education in the 1960s. White schoolchildren read A Child's History of Rhodesia (1925) by Myfanwy Williams and First Steps in Civilising Rhodesia (1940) by Jeannie M. Boogie.[128]

Peter Godwin, who was born in Salisbury (now Harare) in 1957 to English and Polish parents, has written several books with a Zimbabwean background, including Rhodesians Never Die (1984), Mukiwa: A White Boy in Africa (1996), When a Crocodile Eats the Sun (2007) and The Fear: Robert Mugabe and the Martyrdom of Zimbabwe (2011). The theme of these books is the impact of political change in Zimbabwe on the country's white community. His writing has been influenced by the death of one of his sisters in a "friendly fire" incident during the Bush War in the 1970s. Alexandra Fuller wrote of her childhood in the 1970s on a Rhodesian farm in the memoir Don't Let's Go to the Dogs Tonight (2002).[131] For Fuller, the land is gendered female: "In Rhodesia we are born and then the umbilical cord of each child is sewn straight from the mother into the ground, where it takes root and grows. Pulling away from the ground causes death by suffocation, starvation. That's what the people of this land believe."[131]

Graham Boynton, who was raised in Bulawayo, wrote Last Days in Cloud Cuckooland (1997), covering the twilight years of white rule in southern Africa and carried extensive interviews with the two major white political protagonists, Ian Smith and Sir Garfield Todd.[132] The late Heidi Holland met Robert Mugabe at a secret dinner, and in 2007 she was one of the few white journalists to be granted an in-depth interview with the president. Holland wrote about her experiences with Mugabe in Dinner with Mugabe (2008).[133] Douglas Rogers chronicled his parents' struggle to hold onto their game farm and backpackers resort in The Last Resort (2009).[134] Lauren St John, best known for her children's novels, wrote the memoir, Rainbow's End: A Memoir of Childhood, War and an African Farm. St John writes about her childhood home in then Rhodesia, Rainbow's End, where the previous family had been murdered. Her account explores growing up during the civil war in the 1970s and on life in a newly-independent Zimbabwe.[135][136]

Music

[edit]"God Save the Queen" was dropped as the national anthem when Rhodesia became a republic in 1970. In 1974, "Ode to Joy" from Beethoven's Ninth Symphony became the tune for the new national anthem, "Rise, O Voices of Rhodesia".[137] Mary Bloom, a local woman provided the lyrics for the anthem.[138] Patriotic folk songs were particularly popular amongst the white community during the Rhodesian Bush War. A leading musical figure was Clem Tholet, who married Ian Smith's stepdaughter Jean Smith in 1967. Tholet became famous for patriotic anthems such as "Rhodesians Never Die", and he enjoyed gold status (for over 60,000 sales) with his first album, Songs of Love & War,[139] recorded at Shed Studios. Another popular folk singer was Northern Rhodesian-born John Edmond, a former soldier of the (Southern) Rhodesian Army, who also enjoyed considerable success during the Rhodesian Bush War. He had hits with patriotic folk songs such as "The U.D.I. Song" from his popular Troopiesongs album.[140] Rhodesian Premier Ian Smith was criticised for singing the Afrikaans folk song, "Bobbe jaan Klim die Berg" ("The Baboon Climbs the Mountain") at an election rally in 1970 in Salisbury (Harare).[141]

Simon Attwell is a Zimbabwean band member of the popular South African group Freshlyground, playing the flute, mbira, sax, and harmonica.[142] Freshlyground combines both African and European musical traditions,[143] and they participated in the 2008 HIFA. Gemma Griffifths, a singer and Harare native based in Cape Town, has been profiled by the BBC.[144]

Concert pianist Manuel Bagorro is the founder and artistic director of Harare International Festival of the Arts. First held in 1999, the Festival was most recently held in April 2008, and was successful in attracting attention to the arts in Zimbabwe at a difficult time.[145]

The jazz composer, bandleader, and trombonist Mike Gibbs was born in Salisbury, Southern Rhodesia. Other internationally successful artists born there include the Royal Ballet prima ballerina Dame Merle Park and actress Susan Burnet, whose grandfather was one of the country's first white settlers.[citation needed]

Performing arts

[edit]Theatre was immensely popular across African colonies amongst bourgeoise white residents, often seeking the culture of European metropoles. The construction of larger theatres boomed in the twentieth century in colonies most populated by white people, such as Kenya, Southern Rhodesia and the copper belt of Northern Rhodesia. 'Little theatres' were also popular; often, they were part of large sporting venues, gymkhana and turf clubs. In 1910, one author remarked on the popularity of theatre amongst Southern Rhodesia's white population: "the local population must have spent a considerable amount on theatre seats. Fifteen professional companies went on tour that year."[146] Theatres in Southern African colonies were usually situated next to a railway line, and the premier European dramatic performance in then Southern Rhodesia took place in the southern region of Bulawayo. The development of rail infrastructure allowed the involvement of entertainers from neighbouring South Africa.[116]

The National Theatre Organisation, formerly The National Theatre Foundation, focussed on Euro-centric theatre productions. These included plays such as A Midsummer Night's Dream and No Sex Please, We're British.[116]

Broadcasting

[edit]In 1960, television was introduced into the then Southern Rhodesia, as Rhodesia Television. It was the first such service in the region, as South Africa did not introduce television until 1976, due to the potential ideological conflicts that it posed. The Rhodesian Broadcasting Corporation took over from Rhodesia Television (RTV) as RBCTV in 1976. As previously, this was a commercial service carrying advertising, although there was also a television licence fee. Television reception was confined mainly to the large cities, and the majority of television personalities and viewers were from the white minority. Both RTV and RBC used the BBC as a model, in that a government department was not responsible for it, but instead, a board of governors (selected by Ian Smith) were.[147] Popular television shows included Kwizzkids, Frankly Partridge and Music Time.[148] Possibly the best-known Director of the RBC was Dr. Harvey Ward. Prior to the introduction of television, RBC had developed a successful radio network, which continued. By 1978, three top white executives had fled overseas, including Dr. Ward, of whom it was said "probably more than any other person, became identified with the right-wing bias on Rhodesia's radio and TV networks."[149] The RBC was later succeeded by the Zimbabwe Rhodesia Corporation, and later in its present form as the Zimbabwe Broadcasting Corporation. The character Horace Von Khute from the British television series Fonejacker is a Rhodesian who works for the police in intercepting a Ugandan bank scammer.

Georgina Godwin, sister of author Peter Godwin, became a well-known broadcast journalist in Zimbabwe, presenting a breakfast television show and hosting a prime time radio show on the state broadcaster, Zimbabwe Broadcasting Corporation until her departure from the country in 2001.[150] She was also a founder of SW Radio Africa, a station based in London with the purpose of broadcasting independently of Zimbabwean state interference.[151] She is books editor for Monocle Radio and presenter of the in-depth author interview show Meet the Writers on the station.[152]

Cinema

[edit]Doris Lessing's Southern Rhodesia novel The Grass is Singing was adapted into a film by the white Zimbabwean director, Michael Raeburn and released in 1980. Despite the majority of the original novel taking place in then Southern Rhodesia and earlier scenes in South Africa, the adaptation was filmed in Zambia and Sweden. The film starred Karen Black and John Thaw as the poverty-stricken white farming couple Mary and Dick Turner, and John Kani as the black houseboy and love-interest of Mary Turner. The film is also known asGräset Sjunger (Swedish) and Killing Heat.[153]

The 1980 film Shamwari, also known as Chain Gang Killings in the United States, is an action thriller about two escaped prisoners, one Black, one white and their developing friendship. The film was set and filmed in Rhodesia, starring several local white actors, such as Tamara Franke in the role of Tracy.[154] Four years later, Franke had a major role in Go for Gold.[155]

The documentary film Mugabe and the White African was released to acclaim in 2009. It deals with a white Zimbabwean farming family working against Mugabe's draconian land reform policies.[156]

In Blood Diamond (2006), Leonard DiCaprio plays Danny Archer, an ex-mercenary, diamond-smuggler and self-proclaimed "Rhodesian", whose parents were murdered on their farm by rebels. The adventure drama film is set in 1999 during the Sierra Leone Civil War.[157] In The Interpreter (2005) by Sydney Pollack, Nicole Kidman plays the lead role of Silvia Broome, a white African and New York-based United Nations interpreter raised in the fictional African republic of Matobo. Matobo is widely considered to be symbolic of Zimbabwe.[158][159]

Beauty pageants

[edit]Miss Rhodesia was the national beauty pageant of Rhodesia and its antecedents. Each year many local white women competed in the competition and it debuted in Miss World in 1959. Rhodesia participated in Miss World 1965, with Lesley Bunting representing the country only days after Rhodesia's Unilateral Declaration of Independence.[160] However, the country was excluded from the competition from 1966 onwards. Beverley Donald Davy, the mother of Chelsy Davy, was crowned the 1973 Miss Rhodesia.[161] Only white women were crowned Miss Rhodesia between 1959-1976, with Connie Makaya becoming the first black Miss Rhodesia in 1977.[162] When Rhodesia transitioned to a majority democracy and became Zimbabwe in 1980, Miss Rhodesia became Miss Zimbabwe. In 2023, Brooke Bruk-Jackson, a white Zimbabwean woman was crowned Miss Universe Zimbabwe. As white people make up less than one percent of Zimbabwe's population, it was a controversial win for some.[163]

Sports

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2023) |

Before 1980, Rhodesian representation in international sporting events was almost exclusively white. Zimbabwean participation in some international sporting events continued to be white-dominated until well into the 1990s. For example, no Black player was selected for the Zimbabwean cricket team until 1995.[164] Rally driver Conrad Rautenbach (son of Billy) won the FIA African Championship, scoring at the Dunlop Zimbabwe Challenge Rally in 2005 and 2006.[165] An iconic event is the all-white Zimbabwean women's field hockey team, captained by Ann Grant (formerly Ann Fletcher) and winning gold medals at the Moscow Olympics in July 1980 (Ann Grant's brother, cricketer Duncan Fletcher, later became manager of the England cricket team).

An exception to this trend during the 1960s and 1970s was in association football, where the national team was predominantly black, with the notable exceptions of the white forward Bobby Chalmers, who captained the team during its unsuccessful attempt to qualify for the 1970 World Cup,[166] and goalkeeper Bruce Grobbelaar.

The professional swimmer, Charlene, Princess of Monaco, competed at the 2000 Sydney Olympics. She was born and raised in Bulawayo, before relocating with her family to South Africa in 1989 when she was twelve years old. However, she represented South Africa at professional sporting competitions.[167] Australian rugby union player David Pocock is also a well-known Zimbabwean, having emigrated to Australia in 2002 at age 14.[168] Pocock would be elected an Australian Senator in 2022. He would renounce his Zimbabwean citizenship to comply with section 44(1) of the Australian Constitution, which forbids parliamentarians from holding dual citizenship.[169]

Involvement in Zimbabwean politics

[edit]Political and economic background

[edit]

During the UDI era, Rhodesia developed a siege economy as the means of withstanding UN sanctions. The country operated a strict system of exchange and import controls, while major export items were channelled through state trade agencies (such as 'the Grain Marketing Board'). This approach was continued until around 1990, at which time International Monetary Fund and World Bank development funding was made conditional upon the adoption of economic liberalisation. In 1991, Zimbabwe adopted the ESAP (Economic Structural Adjustment Programme), which required privatisation, the removal of exchange and import controls, trade deregulation and the phasing out of export subsidies.[170] Up until the time of independence, the economy relied mainly on the export of a narrow range of primary products, including tobacco, asbestos and gold. In the post-independence period, the world markets for all these products deteriorated, and it was hoped that the ESAP would facilitate diversification.[171]

ESAP and its successor ZIMPREST (Zimbabwe Programme for Economic and Social Transformation) caused considerable economic turbulence.[172] Some sectors of the economy did benefit, but the immediate results included job losses, a rise in poverty, and a series of exchange rate crises. The associated economic downturn caused the budget deficit to rise, which put pressure on public services, and the means used to finance the budget deficit caused hyperinflation. These factors created a situation in which many bright and qualified Zimbabweans (both black and white) had to look abroad for work opportunities.[173]

Zimbabwean politics since 1990 have therefore been conducted against a background of economic difficulty, with the manufacturing sector (in particular) being 'hollowed out'. However, some parts of the economy continue to perform well: the Zimbabwe stock exchange and property market have experienced minor booms, while outsiders are coming to invest in both mining and land operations.[174]

In the period immediately after independence, some white political leaders (such as Ian Smith) sought to maintain the identity of white Zimbabweans as a separate group. In particular, they wished to maintain a separate "white roll", maintaining the election of 20 seats in parliament reserved for white people; this was abolished in 1987. Despite this, a number of white Zimbabweans embraced the political changes, and many even joined Zanu-PF in the 1980s and 1990s: for example, Timothy Stamps served as Minister of Health in the Zimbabwean government from 1986 to 2002.[175] Denis Norman held several cabinet positions; Minister of Agriculture (1980-1985, 1995-1997), Minister of Transport (1990-1997) and Minister of Power (1992-1997).[176]

Wealthy Zimbabweans

[edit]In the 2000s, an elite network of white businessmen and senior military officers became associated with a faction of ZANU-PF identified with Emmerson Mnangagwa, a former Security Minister and later Speaker of Parliament. Mnangagwa was described by reporters of the Daily News as "the richest politician in Zimbabwe".[177] He is believed to have favoured the early retirement of President Mugabe, and a conciliatory approach towards the regime's domestic opponents; this line has displeased other elements in ZANU-PF. In June 2006, John Bredenkamp (a prominent former Mnangagwa associate) fled Zimbabwe in his private jet, after government investigations into the affairs of his Breco trading company were started.[178] Bredenkamp returned to Zimbabwe in September 2006, after his passport was returned by court order.[179]

In July 2002, 92 prominent Zimbabweans were subject to EU "smart sanctions", intended to express disapproval of various Zimbabwe government policies. These persons were banned from the EU, and access to assets they own in the EU was frozen.[180] Ninety-one of those on the blacklist were black, and one was white: Dr. Timothy Stamps.

Many observers found the EU's treatment of Dr. Stamps to be curious, given that by July 2002 he was retired from active politics and a semi-invalid. In addition, Stamps was widely considered to be a highly dedicated doctor who had never been implicated in any form of wrongdoing.[181] The same observers found it equally strange that the EU Commission did not include the wealthy white backers of Mugabe on the list.[clarification needed][182]

Political representation

[edit]From around 1990 onwards, mainstream white opinion favoured opposition politics[183] to that of Mugabe's ZANU party, who controlled the government. White Zimbabweans sought to vote for liberal economics, democracy and the rule of law. White people had lain low in the immediate post-independence period, but, in 1999 they recognised a common disquiet with the majority of people over ZANU excesses in government, and gave whites an opportunity to vote for an opposition, which initially grew out of the trade union movements who were enabling citizens to have a voice and vote with the majority of Zimbabweans.[184] White Zimbabweans played a significant role in the campaign of the opposition MDC party, which almost won the election.[185] Radical elements in the country perceived the MDC project to have been an attempt to restore a limited form of white minority rule, and this produced a violent backlash.[186][187]

The late Roy Bennett, a white farmer forced off his coffee plantation after it was overrun by radical militants and then expropriated, won a strong victory in the Chimanimani constituency (adjoining the Mozambican border) in the 2000 general election. Bennett (a former Conservative Alliance of Zimbabwe member) won his seat for the Movement for Democratic Change, and was one of four white MDC constituency MPs elected in 2000.[188][189] Bennett died in a helicopter crash in Raton, New Mexico, United States in 2018.[190]

Other white MPs elected in 2000 included David Coltart (a prominent human rights lawyer and founding legal secretary of the MDC) and Michael Auret (a civil rights activist of long standing, who had opposed white minority rule in the 1970s). Trudy Stevenson was a white American who had lived in Uganda until 1972, before fleeing from the regime of Idi Amin.[191] Stevenson served as the MDC's Secretary for Policy and Research before being elected to Parliament. In July 2006, after attending a political meeting in the Harare suburb of Mabvuku, Stevenson was attacked, suffering panga wounds to the back of her neck and head. The MDC leadership immediately claimed that the attack was carried out by ZANU militants; however, while recovering in hospital, the MP for Harare North positively identified her assailants as members of a rival faction of the MDC. This incident illustrates the violent and faction-ridden nature of Zimbabwean politics.[192] Zimbabwean politicians routinely accuse each other of murder, theft, electoral fraud, conspiracy and treason; it is often difficult to know the truth of such stories.[193] Eddie Cross was also elected to parliament in 2000 before retiring from politics in 2018.[194][195] Cross, a leading economist, served as the MDC's Economic Secretary and shadow finance minister.[196] In the Parliamentary and Presidential elections, Cross, and Coltart were re-elected to their seats and a white Zimbabwean farmer, Iain Kay took the seat of Marondera Central.[197][198] Stevenson lost her seat in Mount Pleasant, Harare.[199] Stevenson served as Zimbabwe's ambassador to Senegal from 2009 until her death in 2019.[200]

In Zimbabwe's current government, the portfolio of Ministry of Youth, Sport, Arts and Recreation is held by Kirsty Coventry, a position she has held since 2018.[201]

See also

[edit]- British diaspora in Africa

- List of white Zimbabweans of European ancestry

- Racism in Zimbabwe

- Zimbabwean diaspora

- Zimbabweans

- White people

- White Angolans

- White South Africans

- White people in Botswana

- White people in Zambia

Notes and references

[edit]Annotations

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Zimbabwe 2024 Population and Housing Census Report, vol. 2" (PDF). ZimStat. Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency. p. 122. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 October 2024.

- ^ a b Crush, Jonathan. Zimbabwe's Exodus: Crisis, Migration, Survival. pp. 5, 25.

- ^ a b David Lucas; Monica Jamali; Barbara Edgar (2011). "Zimbabwe's Exodus to Australia" (PDF). 34th AFSAAP Conference, The Australian National University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 January 2015.

- ^ https://www.zimstat.co.zw/wp-content/uploads/Demography/Census/2022_PHC_Report_27012023_Final.pdf

- ^ All 59 Die on Rhodesia Airliner Shot Down by Missile The New York Times. 13 February 1979

- ^ Strong Action Hinted By Rhodesian Forces For Attack on Airliner The New York Times. 16 February 1979

- ^ 12 White Teachers and Children Killed by Guerrillas in Rhodesia The New York Times. 25 June 1978

- ^ Rhodesia managing despite sanctions The New York Times. 31 January 1966

- ^ Britain and Rhodesia The New York Times. 8 March 1976

- ^ U.N. Action on Rhodesia Bars Participation in Olympic Games The New York Times. 8 June 1968

- ^ Rhodesia Is Outraged The New York Times. 24 August 1972

- ^ Olympics Exclude Rhodesia The New York Times. 23 May 1975

- ^ Brownwell, Josiah (2011). The Collapse of Rhodesia: Population Demographics and the Politics of Race. London: I.B. Tauris. pp. 3, 51. ISBN 978-1-84885-475-8.

- ^ The New Americans: A Guide to Immigration Since 1965. 2007. p. 309.

- ^ "Zimbabwe's only white minster [sic] says insults against whites continue at top government level". Fox News. 26 March 2015. Archived from the original on 5 March 2013.

- ^ United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. "Refworld - Zimbabwe: Dual citizenship". Refworld.

- ^ Farmer, Ben; Thornycroft, Peta (4 September 2023). "Hundreds of white farmers return to Zimbabwe in boost for agriculture". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 15 December 2023.

- ^ This is a journey: the geography of Zimbabwe

- ^ Masaka, Dennis (2011). "ZIMBABWE'S LAND CONTESTATIONS AND HER POLITICO-ECONOMIC CRISES: A PHILOSOPHICAL DIALOGUE". S2CID 31409283.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ Madimu, Tapiwa; Msindo, Enocent; Swart, Sandra (3 September 2018). "Farmer–Miner Contestations and the British South Africa Company in Colonial Zimbabwe, 1895–1923". Journal of Southern African Studies. 44 (5): 793–814. doi:10.1080/03057070.2018.1500747. ISSN 0305-7070. S2CID 149912083.

- ^ "A country in the midst of change". CBC News. 16 September 2008. Retrieved 14 March 2023.

- ^ Muyengwa, Loveness (2013). "A critical analysis of the impact of the fast track land reform programme on children's right to education in Zimbabwe". S2CID 153015040.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ "Zimbabwe's White farmers: Who will pay compensation?". BBC News. 16 May 2019. Retrieved 14 March 2023.

- ^ Multinational Monitor, April 1981 :Zimbabwe's government wins confidence Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Official Year Book of the Colony of Southern Rhodesia, No. 1, 1924 (Art Printing and Publishing Works, Salisbury, 1924)

- ^ Appiah, Anthony (8 March 2024). Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-517055-9.

- ^ Selby, Angus (2006) "White farmers in Zimbabwe 1890-2005." PhD Thesis, University of Oxford: p. 60 Archived 15 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Selby thesis: p52 Archived 15 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Brownwell, Josiah (2011). The Collapse of Rhodesia: Population Demographics and the Politics of Race. London: I.B. Tauris. pp. 3, 27, 51. ISBN 978-1-84885-475-8.

- ^ Rhodesia Immigration Rises The New York Times. 23 April 1972

- ^ Selby thesis: p58 Archived 15 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ RHODESIA: MASSIVE IMMIGRATION PLAN LAUNCHED AS ACCOMMODATION FOR EUROPEANS LIES VACANT IN SALISBURY. (1974) British Pathe. 1974

- ^ If only ... Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, The Guardian, 25 November 2007

- ^ Selby thesis: p59 Archived 15 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ BBC report: UDI of Rhodesia, 1965 Archived 10 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "From Civilization to Segregation: Social ideals and social control in Southern Rhodesia, 1890–1934" by Carol Summers, Ohio University Press, 1994, ISBN 0-8214-1074-1

- ^ Gender and History, 2005 :article by Lucy Bland on black-white sex, see p3 Archived 19 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Guardian: Obituaries: Sir Garfield Todd Archived 3 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Robin Wright (17 May 1976). "Propoganda [sic]: The Other Rhodesian War". aliciapatterson.org. Archived from the original on 11 September 2010.

- ^ "The Governmental System of Southern Rhodesia", by D.J. Murray, OUP, 1970

- ^ Selby thesis: p66 Archived 15 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Irish Examiner report: 2002 census returns

- ^ "A Chronicle of Modern Sunlight", author W.G. Eaton published by Innovision, Rohnert Park, California, 1996

- ^ Ian F. W. Beckett, The Rhodesian Army: Counter-Insurgency 1972–1979 Archived 9 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine (paragraph 17)

- ^ White Emigration From Rhodesia Sets Record of 1,582 in October The New York Times. 28 November 1978

- ^ White Emigration From Rhodesia Is Rising Sharply The New York Times. 14 November 1978

- ^ Young White Rhodesians Are Streaming to Britain The New York Times. 13 March 1979

- ^ Selby thesis: p117, fig2.3 Archived 15 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Selby thesis: p125 Archived 15 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Whose Kith and Kin Now?, Peter Godwin, Sunday Times, 25 March 1984

- ^ W. G. Eaton, A Chronicle of Modern Sunlight (Innovision, Rohnert Park, California, 1996)

- ^ To White Exiles There'll Always Be A Rhodesia Archived 3 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times, 15 January 1982

- ^ "Rhodie oldies". New Internationalist. 1985. Retrieved 29 October 2007.

- ^ Selby thesis: p194 Archived 15 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Selby thesis: p126 Archived 15 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ SADC newsletter: Eddie Cross interview Archived 22 July 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ The Observer :13 April 2008, Zimbabwe's decade of horror Archived 9 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ NewsPlanet, June 1998 :Sodomy Laws Archived 11 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Being a 'faggot' in homophobic Zimbabwe Archived 24 February 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Mail & Guardian, 9 June 1998

- ^ The Guardian, 9 June 2006: Tycoon flees Zimbabwe in private jet Archived 24 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Zimnews :report on Billy Rautenbach Archived 7 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Daily Telegraph report: Charles Davy defends business interests

- ^ The Zimbabwean 2005 :see para 5

- ^ UN report: – Zimbabwe involvement in DRC minerals

- ^ House of Commons, 18 November 2002 :debate on Zimbabwe Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ The Zimbabwean, 2005 :business backers of ZANU-PF

- ^ UK Parliament: Letter to the Clerk of the Committee from Mr Barry Lennox, 15 July 2004 Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ The Guardian, 27 February 2006 :Zimbabwean farmers in Zambia Archived 16 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ The Guardian, 22 July 2006 :Zambian tourism sector grows at expense of Zimbabwe

- ^ Elderly Britons given lifeline out of Zimbabwe The Times. 18 February 2009

- ^ Britain defends help for elderly leaving Zimbabwe[permanent dead link] CBS News. 6 March 2009 [dead link]

- ^ Should I stay or should I go: what every white Zimbabwean asks[dead link] The Times. 18 February 2009

- ^ Godwin, Peter (2006). When A Crocodile Eats The Sun. Picador.

- ^ The Telegraph, 20 January 2006 :Now aristocrats will be evicted for living too close to Mugabe Archived 7 July 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ The Telegraph, 2 February 2006 : Mugabe moves against white city people

- ^ Mail & Guardian, 1 April 2007 : Zim police detain scores of teenagers[permanent dead link]

- ^ McGreal, Chris (24 June 2008). "Voters left with little choice as the terror goes on". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ^ Selby thesis p62, fig1.6 Archived 15 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Online :the Zimbabwean Land Issue

- ^ Human Rights Watch report Fast Track Land Reform Archived 16 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Selby thesis p318 Archived 15 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ The Guardian, 4 January 2007 Mugabe lets white farmers back Archived 28 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Selby thesis p321 Archived 15 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Selby thesis p327 Archived 15 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Selby thesis :s6.4 'Assessing the fast track land redistributions', p314, notably Figure 6.2, p316 Archived 15 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ The Guardian, 27 February 2006 Zimbabwean farmers in Zambia Archived 16 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ The Sunday Times, 22 June 2008 Lamb, Christina (22 June 2008). "Whites huddle and pray as mob closes in". The Times. London. Retrieved 6 April 2010.[dead link]

- ^ The Daily Telegraph, 26 June 2008 Weston, Louis (26 June 2008). "Zimbabwe's last white farmer forced to quit". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 30 June 2008. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ^ The Daily Telegraph, 29 June 2008 Thornycroft, Peta (29 June 2008). "Ben Freeth, a British-born farmer, is abducted in Zimbabwe". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 4 July 2008. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ^ "White Zim farmers attacked". Archived from the original on 1 July 2008.

- ^ The Times 30 June 2008Raath, Jan (30 June 2008). "Farmer who exposed terror, Ben Freeth, is kidnapped with family". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 12 October 2008. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ^ The Daily Telegraph 2 July 2008Weston, Louis (1 July 2008). "Zimbabwe: Battered white farmers vow to battle on against Robert Mugabe". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ^ The Times 30 November 2008Shaw, Sophie (30 November 2008). "British woman, 74, beaten to death in 'Wild West' Zimbabwe". The Times. London. Retrieved 6 April 2010.[dead link]

- ^ President Emmerson Mnangagwa promises to pay compensation for land grabs and clean up Zimbabwe's 'poisoned politics' as he is sworn in The Telegraph. 24 November 2017. Archived 25 November 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ white farmer gets land back under Zimbabwe's new leader The Independent. 28 January 2018. Archived 25 November 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Mnangagwa on land: 'We don't think along racial lines... it's outdated' News24. 26 January 2018

- ^ Hundreds of white farmers return to Zimbabwe in boost for agriculture The Telegraph. 4 September 2023

- ^ "Racism against white Zimbabweans reach shocking levels". Zimdiaspora.com. 20 September 2010. Archived from the original on 24 September 2010. Retrieved 22 January 2016.

- ^ Hyslop, Leah (11 June 2010). "White farmers in Zimbabwe struggle against increasing violence". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022.

- ^ "Zimbabwe's white farmers still target of violence". News.yahoo.com. 5 September 2011. Retrieved 22 January 2016.

- ^ "Zimbabwe". genocidewatch.com. 7 June 2012. Archived from the original on 16 September 2012.

- ^ "Zimbabwe: Go back to England, Mugabe tells Whites". New Zimbabwean. 5 September 2014. Retrieved 22 January 2016.

- ^ Farmer, Ben; Thornycroft, Peta (4 September 2023). "Hundreds of white farmers return to Zimbabwe in boost for agriculture". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 13 December 2023.

- ^ a b c 15,000-Strong Afrikaner Community Finds Tolerance in Zimbabwe The Washington Post. 4 January 1984

- ^ Pieter van der Byl The Guardian. 30 November 1999

- ^ A Short Thousand Years: The End of Rhodesia's Rebellion, Paul L. Moorcraft, Galaxie Press, 1979, page 228

- ^ Of Boers, rockspiders and exceptions Vrye Weekblad. 29 September 2023

- ^ a b c d 6. White Rhodesia Columbia University Press. 2007

- ^ a b c d Mervyn Trappler: A look back at the Jews of Rhodesia Jerusalem Post. 30 June 2022

- ^ a b c d Zimbabwe's Jews: A shtetl in Africa The Jerusalem Post. 10 January 2018

- ^ Jewish tradition thrives at Zimbabwe school with no Jews South African Jewish Report. 29 November 2018

- ^ a b c d e Cultural Relations and Greek Community Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Greece)

- ^ a b Shadowed World Of the White Rhodesians The New York Times. 12 December 1965

- ^ Parliament of Zimbabwe (3 December 2013). "Names Alteration Act 10/14: Part II: Municipalities And Municipal Councils: Old–Municipality of Sinoia; New–Municipality of Chinhoyi" (PDF). Harare: Parliament of Zimbabwe. Archived from the original (Archived from the original on 3 December 2013) on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- ^ Rhodesia losing whites in a rise of emigration The New York Times. 28 November 1976

- ^ a b c Byam, L. Dale (1999). Community in Motion: Theatre for Development in Africa. Greenwood Publishing Group.

- ^ Jason Cowley (4 March 2007). "When a Crocodile Eats the Sun: A Memoir by Peter Godwin - reviewed". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 January 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g Empire, nation, gender and romance : the novels of Cynthia Stockley (1872-1936) and Gertrude Page (1873-1922) University of Cape Town. 1997

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q 13. White Rhodesian Poetry Columbia University Press. 2007

- ^ Tragedy on the Veld The New York Times. 10 September 1950