Western and Atlantic Railroad

| |

Map of the W&A, with locations of different events in the Great Locomotive Chase marked. The road did not extend beyond Atlanta and Chattanooga prior to its lease to the NC&StL. | |

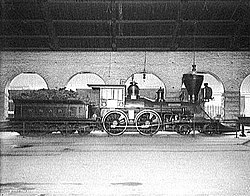

One of the W&A's famous locomotives, The General, on display in the railroad's Union Depot in Chattanooga | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Headquarters | Atlanta, Georgia |

| Reporting mark | W&A |

| Locale | Tennessee, Georgia |

| Dates of operation | 1836–present |

| Successor | Nashville, Chattanooga and St. Louis Railway |

| Technical | |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge |

| Previous gauge | 5 ft (1,524 mm) and 4 ft 9 in (1,448 mm)[1] |

| Length | 138 miles (222 km) |

The Western & Atlantic Railroad of the State of Georgia (W&A) is a railroad owned by the State of Georgia and currently leased by CSX, which CSX operates in the Southeastern United States from Atlanta, Georgia, to Chattanooga, Tennessee.

It was founded on December 21, 1836. The city of Atlanta was founded as the terminus of the W&A, with the terminus marked with the Atlanta Zero Mile Post. The line is still owned by the State of Georgia from Atlanta to CT Tower in Chattanooga; it is leased by CSX Transportation.

The W&A Subdivision is a railroad line leased by CSX Transportation in the U.S. states of Tennessee and Georgia. The line runs from Chattanooga to Marietta, Georgia for a total of 119.1 miles (191.7 km). At its north end, it continues south from the Chattanooga Subdivision of the Nashville Division and at its south end it continues south as the Atlanta Terminal Subdivision (Chart A).[2][3]

This line, originally built to 5 ft (1,524 mm) gauge,[4] is famous because of the Great Locomotive Chase, also referred to as Andrews' raid, which took place on the W&A during the American Civil War on the morning of April 12, 1862.

Establishment

[edit]In 1836, the Georgia General Assembly voted to build the Western & Atlantic Railroad of the State of Georgia to provide a link between the port of Savannah and the Midwest.[5] The initial route of that state-sponsored project was to run from Chattanooga to a spot east of the Chattahoochee River, in present-day Fulton County. The plan was to eventually link up with the Georgia Railroad from Augusta and the Macon and Western Railroad, which ran from Macon to Savannah. An engineer was chosen to recommend the location where the Western & Atlantic line would terminate. Once he surveyed various possible routes, he drove a stake into the ground near what is now Forsyth and Magnolia Streets. The zero milepost was later placed at that spot. In 1842, the zero milepost was moved to a spot immediately adjacent to the current southern entrance to Underground Atlanta.[6] The area developed into a settlement, known as "Terminus", literally meaning "end of the line". In 1843, the small settlement of Terminus was incorporated as the city of Marthasville. Two years later, by act of Georgia's General Assembly, the city was renamed "Atlanta".[7] The railroad made significant contributions to the development of north Georgia.[8]

Funding source for public education

[edit]In 1857, Joseph E. Brown was elected Governor of Georgia. He supported free public education for poor white children, believing that it was key to the development of the state. He asked the state legislature to divert a portion of the profits from the state-owned Western & Atlantic, to help fund the schools.[9] Most planters did not support public education and paid for private tutors and academies for their children. That resistance, and inadequate railroad income, initially thwarted governor Brown's education reform efforts. The Western and Atlantic Railroad was mismanaged at the time, and unable to produce the income Brown required to fund his public education proposal. In 1858, Governor Brown appointed John W. Lewis to the position of Superintendent of the state-owned railroad. Lewis had the skills of a successful businessman, and immediately undertook reforms to turn around the failing enterprise. The railroad, said to be in "dire financial straits", required the same strict economic controls Lewis had practiced in his private businesses. In the three years that Lewis ran the railroad, he was able to turn the business into a money making enterprise, paying $400,000 per year into the state treasury.[10]

In 1861, Brown was up for re-election to a third term. It was at this time, during the re-election campaign, that Western & Atlantic Railroad Superintendent John Woods Lewis, an old friend of the governor, decided to resign from the railroad. The timing could not have been worse. Fearing that Lewis' resignation would be interpreted negatively, the governor requested that Lewis keep the resignation a secret. But the resignation letter was leaked to the press, causing a rift between the two old friends. Brown wrote to Lewis saying "I did not deserve this at your hands, and I confess I felt it keenly...I do not attribute improper motives, but only say the coincidence was an unfortunate one for me".[11]

Leasing

[edit]Through 1870, it was called the State Road, and was operated directly by the state under a superintendent appointed by and reporting to the governor of Georgia. On December 27 of that year, operations were transferred to the Western & Atlantic Railroad Company, a group of 23 investors including Georgia's wartime governor Joseph E. Brown, who leased it (both tracks and rolling stock) from the state for $25,000 per month. This expired 20 years later, when the Nashville, Chattanooga & St. Louis (NC&StL) leased it for 29 years. The railroad that was handed over to the NC&StL was in very poor condition. The locomotives that were transferred consisted only of those listed on the 1870 lease as property of the State, with all of the more modern engines purchased under Gov. Brown's Western & Atlantic Railroad Company having been sold to other railroads. While most of the passenger equipment was usable, almost all of the locomotives were condemnable and all of the freight cars were scrapped. The value of the locomotives was disputed for some 20 years. A major change in the new lease in 1890 stipulated that all improvements made to the road by the lessee would become property of the state at the termination of the lease. Included in the definition of improvements were modifications to the facilities, right of way and new equipment purchased for use over that line, including passenger cars, freight cars, and locomotives. As it turned out, the NC&StL continued to hold the lease to the Western & Atlantic Railroad until it was absorbed by its parent company, the Louisville and Nashville Railroad, which was itself owned by the Atlantic Coast Line-one of the principal railroads in the Family Lines System and later CSX Transportation, which continues to operate the line as the Western & Atlantic Subdivision. CSXT signed the current lease on the W&A from the State of Georgia in May 1986, set to expire on December 31, 2019.[12] On Sept 7th, 2018, the owner and CSX announced they had reached an agreement to renew the lease for 50 more years, starting in 2020 at $1 million a month, and rising annually thereafter.

After being captured by the Union in mid-1864 and until the end of the war in 1865, the line was briefly operated by the United States Military Railroad.

Distances of depots from Atlanta (1867 list and 2008 list)

[edit]| # | Name | Milepost (1867) | Milepost (2008) | Notes |

| 1 | Marietta, Georgia | 20 | 20 | begun in 1838, completed 1842 |

| 2 | Big Shanty-renamed Kennesaw, Georgia approx. 1870 | 28 | 28 | Chase starts in front of the Lacy Hotel |

| 3 | Acworth, Georgia | 35 | 35 | |

| 4 | Allatoona, Georgia | 40 | 40 | Near Lake Allatoona |

| 5 | Emerson, Georgia | 45 | 45 | |

| 6 | Cartersville, Georgia | 47 | 47 | |

| 7 | Cass Station-unincorporated Cassville, Georgia | 52 | 52 | |

| 8 | Kingston, Georgia | 59 | 59 | |

| 9 | Adairsville, Georgia | 69 | 69 | |

| 10 | Calhoun, Georgia | 79 | 79 | |

| 11 | Resaca, Georgia | 84 | 84 | |

| 12 | Tilton-unincorporated Dalton, Georgia | 90 | 90 | |

| 13 | Dalton, Georgia | 99 | 99 | |

| 14 | Tunnel Hill, Georgia | 107 | 108 | Chetoogeta Mountain Tunnel completed May 7, 1850; tunnel dug from both ends, bores met on October 31, 1849; first through passenger train passed through May 7, 1850 |

| 15 | Ringgold, Georgia | 115 | 114 | Chase ends at 116.4 |

| 16 | Graysville, Georgia | 121 | 121 | |

| 17 | Chickamauga, Georgia | 126 | 126 | |

| 18 | Chattanooga, Tennessee | 138 | OWA 137.3/OOJ 149.4 | End W&A Sub, End Chattanooga SD (at Wheland, completed Dec. 1849 |

Trains departed from Atlanta at 8:50 a.m. and 7 p.m. and arrived there at 1:35 a.m. and 1:15 p.m. Not much has happened in between 1867 and now, track realignments in some areas resulted in height clearances and track improvements.

Great Locomotive Chase

[edit]

On the morning of April 12, 1862, the locomotive General was stopped at Big Shanty, Georgia (now Kennesaw) so that the crew and passengers could have breakfast. During this time, James J. Andrews and his Union raiders (Andrews Raiders), stole the General. The only damage the raiders did involved cutting telegraph lines and raising rails, although an attempt to burn a covered bridge failed. The train's conductor, William A. Fuller, chased the General by foot and handcar. At Emerson, Georgia, Fuller commandeered the Yonah and rode it north to Kingston, Georgia. At Kingston, conductor Fuller got the William R. Smith and headed north to Adairsville. The tracks were broken by the raiders two miles (3.2 km) south of Adairsville and Fuller had to run the two miles on foot.

At Adairsville, Fuller got the locomotive Texas and chased the General. While all of this was happening, Andrews' Raiders were cutting the telegraph wires so no transmissions could go through to Chattanooga. With the Texas chasing the General in reverse, the chase went through Dalton, Georgia, and Tunnel Hill, Georgia.

At milepost 116.3 (north of Ringgold, Georgia), Andrews' Raiders abandoned the General and scattered from the locomotive just a few miles from Chattanooga. After the chase, Andrews and most of his raiders were caught. After they were found guilty, Andrews and seven members of his party were executed by hanging. Of the remaining 14 raiders, several escaped and made it back to US Army lines and the remainder were exchanged as prisoners of war. These men were the first soldiers to be awarded the Medal of Honor.

After the chase

[edit]When the chase was over, both engines returned to service. After the "General"'s service with the W&A was over, she retired to the Nashville, Chattanooga and St. Louis Railway Union Depot in Chattanooga. In 1890, the Nashville, Chattanooga and St. Louis Railway overhauled the General and provided the locomotive for public events and to promote the line's Civil War history (to drum up the tourism trade) up through the 1930s. In 1962, 100 years after the chase, the L&N performed work necessary to allow the locomotive to operate under her own power for a series of appearances marking the 100th anniversary of the Andrews Raid. The premier appearance was her run from Atlanta to Chattanooga over the Western & Atlantic Railroad. After this run, the General would make excursion trips on various rail lines across the eastern US through most of the 1960s. In the late 60s, the General was to go to Kennesaw for another appearance when the City of Chattanooga officials halted it. The engine was put in storage in Louisville while a legal battle for its custody ensued. In 1971 the United States District Court confirmed the right of the railroad to dispose of the locomotive as it saw fit and it was moved to Kennesaw, Georgia (via a route bypassing Chattanooga) in 1972 where it was placed in the Big Shanty Museum. The Texas was renamed Cincinnati and was retired shortly after the turn of the century, and was stored on a siding. In 1911, it was moved to Grant Park and later placed in the Atlanta Cyclorama.

Re-gauging

[edit]Prior to the Civil War, the rail gauge of most railroads in the South were 5 ft (1,524 mm) broad gauge. In 1886, the change to the Northern standard gauge of 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) was mandated on June 1, and the W&A accomplished this along all 138 miles (222 km) in less than 24 hours, beginning at 1:30 p.m. on May 31 and finishing at 10 a.m. the next morning.[13] This was done by over 400 men, prying up one rail and moving it closer to the other by exactly 3 inches (76 mm), leaving a compatible gauge of 4 ft 9 in (1,448 mm). The General and many other locomotives were also re-gauged at this time.

W&A in modern times

[edit]

Aside from a few track realignments by the Nashville, Chattanooga and St. Louis Railway, the W&A has changed little since 1862. The most significant changes were realignment during the creation of Lake Allatoona, with the tracks through Allatoona Pass removed. The Etowah River bridge has also been replaced. The famed Chetoogeta Mountain Tunnel in Tunnel Hill, Georgia, was abandoned in 1928; it was too small to accommodate the larger trains of the era, and a new tunnel was built nearby.

A marker indicating where the chase began is near the Big Shanty Museum in Kennesaw, Georgia. A marker for where the chase ended is at Milepost 116.3, north of Ringgold, Georgia, which is not far from the recently restored depot at Milepost 114.5. A monument dedicated to Andrew's Raiders is located at the Chattanooga National Cemetery; it has the General on top of the monument and a brief history of the great locomotive chase.

Chief executives

[edit]While under construction the road was led by the Chief Engineer and when construction was completed by the Superintendent.

Chief Engineers

[edit]- Stephen Harriman Long: May 12, 1837 – November 3, 1840

- James S. Williams: 1841

- Charles Fenton Mercer Garnett: February 7, 1842 – December 31, 1847[14]

- William L. Mitchell: January 1, 1848 – 1852[15]

Superintendents

[edit]- William L. Wadley: February 2, 1852 – February 1, 1853[16]

- Geoerge Yonge: 1853 – ?

- John Wood Lewis: January 1, 1858 – Dec. 1860

- John Sharpe Rowland: October 1, 1861 – September 18, 1863

- George D. Phillips: November 5, 1863 – ?

See also

[edit]- Chetoogeta Mountain Tunnel

- List of railroads of the Confederate States of America

- Streight's Raid

- Western and Atlantic Depot (Dalton, Georgia)

References

[edit]- ^ "The Days They Changed the Gauge". southern.railfan.net. Retrieved 2016-11-16.

- ^ radioreference.com, CSX W&A Sub

- ^ multimodalways.org, CSX Atlanta Division Timetable

- ^ "Confederate Railroads - Western & Atlantic". csa-railroads.com. Retrieved 2016-11-16.

- ^ "Creation of the Western and Atlantic Railroad". About North Georgia. Golden Ink. Archived from the original on 2019-06-08. Retrieved 2007-11-12.

- ^ "Historical Markers by County - GeorgiaInfo". georgiainfo.galileo.usg.edu. Retrieved 2016-11-16.

- ^ "Atlanta | New Georgia Encyclopedia". georgiaencyclopedia.org. Retrieved 2016-11-16.

- ^ Gates, Frederick B. (2007). "The Impact of the Western & Atlantic Railroad on the Development of the Georgia Upcountry, 1840-1860". Georgia Historical Quarterly. 91 (2): 169–184. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- ^ Carole E. Scott, "Joseph E. Brown" Archived 2018-01-24 at the Wayback Machine, About North Georgia website, 2016; accessed December 16, 2016

- ^ Lucian Lamar Knight (1917). The period of expansion or Georgia in the process of growth, 1802-1857 (continued) ; The period of division or Georgia in the assertion of state rights, 1857–1872 ; The period of rehabilitation or Georgia's rise from the ashes of war, 1872–1916 ; Georgia miscellanies. Lewis Publishing Company. p. 717.

- ^ Joseph Howard Parks (1 March 1999). Joseph E. Brown of Georgia. LSU Press. pp. 164–165. ISBN 978-0-8071-2465-9.

- ^ Moody's Transportation Manual, 1992, p. 451

- ^ Southern Railfan, The Days They Changed the Gauge

- ^ Johnston, p.28

- ^ Johnston, p.29

- ^ Johnston, p.44

Bibliography

[edit]- Johnston, James Houstoun (1931). Western & Atlantic Railroad of the State of Georgia. Atlanta.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

External links

[edit]- Building the Western & Atlantic Railroad

- Western & Atlantic Railroad

- Western & Atlantic Railroad in the Civil War Archived 2008-04-18 at the Wayback Machine

- Western & Atlantic Depot historical marker

- State R.R. Survey historical marker

- The original records of the Western & Atlantic Railroad are housed at the Georgia Archives Archived 2018-06-26 at the Wayback Machine.

- Georgia (U.S. state) in the American Civil War

- Georgia (U.S. state) railroads

- History of Atlanta

- Non-operating common carrier freight railroads in the United States

- Predecessors of the Louisville and Nashville Railroad

- Predecessors of the Nashville, Chattanooga and St. Louis Railway

- Railway companies established in 1836

- Railway lines in Atlanta

- 5 ft gauge railways in the United States

- Tennessee railroads

- 4 ft 9 in gauge railways in the United States

- 1836 establishments in Georgia (U.S. state)

- American companies established in 1836

- Great Locomotive Chase