West African mosques

The Mosques of West Africa are mosques located in the region of West Africa that encompasses Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone, and Togo. The architecture of these mosques differ from mosques around the world as they have unique building practices and cultural roles. Islam in Africa spread to the region around the 10th century and established the first written language of West Africa.[1] The spread of Islam into West Africa had impacted scholarship, commerce, and utilized indigenous traditions unique to the area.[1] Sudanese Jihads had formulated their own branch of Islam, establishing powerful Islamic states.[1] Islam is one of the major religions present in Africa, with mosques being architectural spaces used for Muslim worship.

West African mosques, commonly made from mud brick, form a unique distinction from other mosques around the world.[2] There are two typical architectural substyles of West African mosques: Sudanese and Sudano-Sahelian. Due to geographical variations within West Africa, building practices differ throughout the region. Features of West African mosques manifest differently depending on the population and climate of their location, from larger, more intricate structures to unadorned, more sculptural forms.[2] Mosques are architectural spaces that serve as the locations for not only Muslim worship but also centers of education, community, commerce, and celebration.[3] While this is a rich and multifaceted topic, there are still many holes in scholarship and not much information has been published on many West African mosques to this day.

Building practices

[edit]

As Islam spread into Africa, West African mosques developed to share certain unifying architectural characteristics, namely the utilization of building materials localized to the environment. One of the main ways we see this in the mosques is through their construction, as they are largely built with mud brick.[2] Sub-Saharan African mosques are formed with materials that lack long term durability.[2] Due to this building technique, more frequent maintenance is necessary. The mosques are also built with wood or palm sticks that protrude from their edifice to help stabilize the structure and act as scaffolding for upkeep due to the mud's reaction in the humid climate of West Africa.[2]

Mud construction is used across West Africa and seen as an exclusively indigenous building material.[2] This specific building resource can be used to form different structures due to its manipulative qualities.[2]

Craftsmen, specifically of the Great Mosque of Djenné, possess extreme levels of talent and artistry in the mud-brick masonry practice.[4] Due to their expertise in their construction of mud bricks, they were able to form distinct building styles representative of West African mosques.[4] Masons of West African mosques were considered middle class due to the skills they possessed but this was dependent on the number of clients they were able to have.[4] Mud brick craftsmen adhered to a specific building season when the mud itself is driest.[4] The building period ranged from January to April, but repair work on the mosques could be done outside of that time.[4] Construction of the mosques of West Africa takes incredible skill, requiring mud brick masons to understand the trade and pass down their knowledge to future generations to ensure its continuation.[4] Within the mud brick mason trade, a sense of community is formed due to its difficulty, time required, and artistic element that is required.[4]

While West African mosques share these features and mainly revolve around a recognizable basic form, there are many ways these building practices can be employed and varied within the region. Places such as the boucle du Niger and Voltaic Basin, in Western Sudan, have a distinct architectural design compared to other mosques of West Africa.[2] Along the equator, these locations span from the ancient emporia to places such as the Niger River and rainforest.[2] They are referred to as Sudanese mosques.[2]

Defining architectural features

[edit]There are two main substyles of West African mosques: Sudanese[5] and Sudano-Sahelian.[6]

Sudanese architecture is defined by its use of pilasters (rectangular pillars on the sides of walls used for decoration), wooden beams known as toron,[7] buttresses with cone-shaped summits, mihrabs, flat roofs, courtyards, sand floors with mats, arches, decorated exteriors, and Tata Tamberma[8] (a defensive West African architecture style that is reminiscent of a fortress by including walls made of earth around the exterior made by the Takyenta people).[6]

Sudano-Sahelian architecture is defined by its use of mudbrick and adobe plaster (a natural material that gives earth walls a hard finish). Within the Sudano-Sahelian style there are five main subgroups: Malian, Songhai, Hausa, Volta basin,[9] and ribāṭ. Malian architecture originates from the Manden groups of southern and central Mali and mainly uses mudbrick in its construction.[10] Songhai architecture comes from the Songhai groups of Niger and Northern Mali and include features such as flat roofs and double niched mihrabs.[10] Hausa architecture is typically found in North and Northwestern Nigeria, Niger, Eastern Burkina Faso, Northern Benin, and Hausain neighborhoods in various countries in West Africa.[10] Hausa architecture is defined by its use of abstract stucco designs, parapets (a small wall along the edge of the roof), and being between one or two stories. Volta basin architecture[9] is built by Gur and Mandé groups. They are defined by their white and black walls, curved turrets, an exterior wall, a single courtyard, and a larger turret near the center of the building.[10] Ribāṭ architecture is a defensive style of building originally used to describe fortifications made in the first few years of the Muslim conquest of the Maghreb, using large walls for defense and a central minaret, a tower traditionally used to project the daily calls for prayer in Islam, designed to be a as a lookout along with its religious connotations.[10]

In some scholarly articles, Ribāṭ architecture is defined as Fortress architecture, but this language mainly arises from Western research and does not cite local cultural reasons for this distinction.[11]

Cultural functions

[edit]Mosques in West Africa are not only places of worship but also serve as important community centers. These spaces can host marketplaces and schools, as well as events such as births, weddings, funerals, and festivals.[3]

The marketplace has been historically intertwined with West African mosques, contributing to the region's economic development and facilitating cultural exchange. In eighteenth century Mampurugu, now known as Ghana, the establishment of the mosque as an economic hub was integral to the area's involvement in trans-Saharan trade. Islamic law governed trade practices, fusing religious and secular activity.[12] Today, one of the most famous markets in Mali takes place each Monday outside of the Great Mosque of Djenné, a tradition that originated in the Middle Ages.[13] Street vendors offer a variety of colorful goods, from traditional foods and medicines to jewelry, gold, and salt from Timbuktu.[14]

The Great Mosque of Djenné also hosts an annual festival known as the Crepissage de la Grand Mosquée. During this event, men and women of all ages participate in the re-plastering of the mosque's exterior.[15] As mud is transported through the streets, young girls wave Malian flags while playing calebasse drums. A guild of masons called the Barey-Ton passes down ancestral knowledge of building practices and magical rituals. The crepissage is blessed by both the Imam and the masons using incantations and talismans.[16]

Some renowned mosques have become popular tourist destinations. The Larabanga Mosque in Ghana is commonly referred to as the "Mecca of West Africa", attracting pilgrims and tourists alike.[17] While the tourism industry has generated revenue for the community, it has resulted in a shift in cultural dynamics, creating tension among locals as some oppose the heavy commodification of such a sacred space.[18]

Significant examples

[edit]Most West African mosques share unifying architectural characteristics based on the practices used to construct them. These include the materials used, and the processes by which the structures are maintained. Depending on the location, climate, and population of the region of a West African mosque, these features present differently.[2]

These examples are some of the mosques in West Africa that have been most widely researched and are currently best understood, or which play prominent roles in their respective countries and communities. There are many examples and styles that have not been included due to a lack of scholarly research and information on the structures. Additionally, the construction of many mosques in West Africa was paid for and backed by other countries and imperial powers; these examples have been omitted here as they do not reflect the vernacular building practices of West Africa.[19]

Great Mosque of Djenné, Djenné, Mali

[edit]

The Great Mosque of Djenné is a monumental hypostyle mosque with a central prayer hall supported by many columns.[20] The mosque appears symmetrical and intricate, with large pointed minarets decorating the front of the building, made out of mud brick with supporting wood beams.[20] These features are often common in populated areas where mosques need to meet the demands of a larger community and more resources can be devoted to the craftsmanship of the structures.[2] Additionally, the community participates in an annual re-claying ceremony and celebration to maintain the mosque, where areas that have been worn down are repaired.[20] The Great Mosque of Djenné is perhaps the most famous mosque in West Africa due to its stature and existence as the largest known mud structure in the world.[20] Due to its fame, this mosque also has the most available scholarship on it out of the Mosques in West Africa.

Sankore Mosque, Timbuktu, Mali

[edit]

The Sankore Mosque is similarly massive to the Great Mosque of Djenne but is built in a sturdy style with pyramidal minarets that create a weightiness at the bottom of the structure.[2] The structure has smoother, flat sides that do not have as many defined ridges. Due to its immense size, wider base, and smoother appearance, this mosque and others of a similar style appear quite dense and have a solid presence in the landscape. This style is common in larger urban regions that were often centers of trade, like Timbuktu, but did not develop into unified city-states.[2] This blockier, heavy building style is somewhat of a bridge between more complex mosques in larger, populated regions, and more sculptural structures in rural areas.[2]

Grand Mosque of Bobo Dioulasso, Burkina Faso

[edit]

The Grand Mosque of Bobo-Dioulasso has prominent minarets that flare outward at their bases and come to a tapered point at their peaks.[2] This mosque is smaller in scale and less monumental, also featuring buttresses and columns with flared bases and overall a less vertical stature.[2] This construction choice is due to the humidity of its location in the southern savannah, and other mosques in the area often share these traits.[2] With greater humidity levels interacting with the mud brick building materials used in the Bobo-Dioulasso Mosque, these shorter, tapering, pillars are important in order to keep the building structurally sound.

Kong Mosque, Kong, Côte d'Ivoire

[edit]The Kong Mosque is very similar in design to The Grand Mosque of Bobo-Dioulasso, with tapered minarets and columns that have wider, sturdier bases. The structure is smaller in scale, and unlike some of its counterparts, makes more extensive use of wood.[2] The Kong Mosque is located in close proximity to a rainforest climate, and as a result of the heavier precipitation the mosque requires even more frequent maintenance and sturdy bottom heavy construction.[2] Additionally, we see a broader utilization of wood in its construction as the material is accessible and provides additional reinforcement needed as a result of the damp climate.[2] These architectural adaptations to a wetter climate give the structure a horizontal design and reduce detail and definition in the structure itself, and also render certain aspects of the mosque nonfunctional, namely the minarets.[2] Instead, they are solid sculptural forms that act as symbols of the call to prayer and do not house a set of stairs leading up the interior of the structure as they usually would.[2]

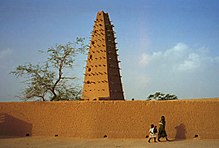

Agadez Mosque, Agadez, Niger

[edit]

The Agadez Mosque has a singular towering minaret at its center, with a wider base and tapered point at the top, considered to be the tallest minaret built from mud brick in existence.[21] The rest of the structure is also made of mud brick, with lower walls that blend into the surrounding buildings. This use of mud brick is particularly ingrained in the city of Agadez, as the region has an extensive ancestral and cultural tradition of using this material, and essentially all buildings in the city are built from mud brick.[21] Due to the homogeneity of architecture in the city, the mosque itself melds with the rest of the buildings, mainly standing out due to the height and monumentality of the singular monumental minaret.

Larabanga Mosque, Larabanga, Ghana

[edit]

The Larabanga Mosque has squat minarets and columns making up its sides, which taper upward in a pyramidal shape but with sides that curve outward creating a bulging effect to its exterior walls. Compared to mosques of similar constructions, the Larabanga mosque is compact in stature, has a very wide base to its structure, and is covered in a layer of smooth white plaster.[22] Wooden supports run horizontally between the columns and buttresses of the building, further contributing to the shorter, horizontal nature of this mosque. These characteristics of the Larabanga Mosque can be attributed to its location's proximity to a humid rainforest climate, requiring further structural reinforcement as well as tapered walls to allow rain to run down the sides of the structure more easily.[22] Additionally, these climate constraints impact the interior of the mosque, which is broken up into smaller areas instead of one large prayer hall, and similar to the Kong mosque, has sculptural minarets rather than functional ones.[22] The Larabanga Mosque is one of the oldest known mosques in West Africa, constructed during the founding of the city of Larabanga, making it an important community site and cultural location for Islam in the region, as well as an example of prototypical mosque architecture in West Africa.[22]

Current scholarship

[edit]There have been fewer scholarly papers focused on West African mosques compared to those in Middle Eastern lands or southern Asia. Along with this lack of research, many of these western-based studies in the past have included outdated terminology or ideas.[23] Past European scholarship has historically failed to explore outside of coastal areas while not being up to standard in their knowledge of West African tradition and architectural culture.[23] While fewer resources have gone to study West African mosques, scholarship has mostly focused on the processes in building these mosques, typically deriving their materials from the nearby area,[2] as well as the cultural practices associated with these mosques.[6] Out of the scholarly field, the Great Mosque of Djenne has been the most published, with its large mud stature giving it fame as well as Djenne's tradition of reapplying the mosque's walls with mud every year.[20]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Falola, Toyin; Jean-Jacques, Daniel, eds. (2015). Africa: an encyclopedia of culture and society. Santa Barbara, Calif: ABC-CLIO, an imprint of ABC-CLIO, LLC. ISBN 979-8-216-04273-0.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x Prussin, Labelle (1968). "The Architecture of Islam in West Africa". African Arts. 1 (2): 32–74. doi:10.2307/3334324. JSTOR 3334324.

- ^ a b Cantone, Cleo (2012). Making and Remaking Mosques in Senegal. doi:10.1163/9789004217508. ISBN 978-90-04-21750-8.[page needed]

- ^ a b c d e f g Marchand, Trevor H. J. (2009). "Negotiating Licence and Limits: Expertise and Innovation in Djenné's Building Trade". Africa. 79 (1): 71–91. doi:10.3366/E0001972008000612. JSTOR 29734391.

- ^ "Sudanese style mosques in northern Côte d'Ivoire". whc.unesco.org. Retrieved 2024-12-10.

- ^ a b c Nizamoglu, Cem (2006-03-31). "West African Mosque Architecture - A Brief Introduction". Muslim Heritage. Retrieved 2024-12-10.

- ^ "Hybrid Typologies: Toron A-frame". Race & Architecture. 2019-11-13. Retrieved 2024-12-10.

- ^ "The Tata Tamberma – History and Architecture – ADRELO: Advancing Resilience in Low Income Housing". sites.psu.edu. Retrieved 2024-12-10.

- ^ a b Saako, Mahmoud Malik. "Islamic Architecture in Northern Ghana".[self-published source?]

- ^ a b c d e "Sudano-Sahelian Architecture." Pan-Africa, mebaatw.github.io/linkinghearts/sudan-sahel-arch/. Accessed 9 Dec. 2024.

- ^ "African architecture - Islam, Christianity, Africa | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 2024-10-19. Retrieved 2024-12-10.

- ^ Davis, David C. (1996). "The Mosque and the Marketplace: An Eighteenth Century Islamic Renaissance in West Africa". Islamic Studies. 35 (2): 135–163. JSTOR 20836938.

- ^ "The Mosque and the Monday Market in Djenne." Kanaga Africa Tours, 18 May 2022, www.kanaga-at.com/en/trip-info/mali-en/the-mosque-and-the-monday-market-in-djenne/.

- ^ Colville, Alex. "Explore the Djenné Market." Google Arts and Culture, artsandculture.google.com/story/explore-the-djenn%C3%A9-market-the-mcubed-initiative/OgWxgjWJWsS5Kg?hl=en. Accessed 9 Dec. 2024.

- ^ Farrag, Engy (December 2017). "Architecture of mosques and Islamic centers in Non-Muslim context". Alexandria Engineering Journal. 56 (4): 613–620. doi:10.1016/j.aej.2017.08.001.

- ^ "Why Does the Great Mosque of Djenné Need to Be Repaired Every Year?" Google Arts & Culture, artsandculture.google.com/story/why-does-the-great-mosque-of-Djenné-need-to-be-repaired-every-year-instrument-for-africa/iAVBFtM7yl3Rtw?hl=en.

- ^ "Ancient Mosques of the Northern Region." Ghana Museums & Monuments Board, www.ghanamuseums.org/ancient-mosques.php#:~:text=Apart%20from%20their%20usual%20role,other%20donations%20for%20the%20community. Accessed 9 Dec. 2024.

- ^ Apotsos, Michelle Moore (December 2016). "New Meanings and Historical Messages in the Larabanga Mosque". African Arts. 49 (4): 8–23. doi:10.1162/AFAR_a_00311.

- ^ Haynes, Jeffrey (28 October 2022). "Religious and Economic Soft Power in Ghana-Turkey Relations". Religions. 13 (11): 1030. doi:10.3390/rel13111030.

- ^ a b c d e Marchand, Trevor H. J. (2015). "The Djenné Mosque: World Heritage and Social Renewal in a West African Town". APT Bulletin: The Journal of Preservation Technology. 46 (2/3): 4–15. JSTOR 43556448.

- ^ a b Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Historic Centre of Agadez." UNESCO World Heritage Centre, 2013, whc.unesco.org/en/list/1268/.

- ^ a b c d Osayimwese, Iothan (5 March 2018). "Iothan Osayimwese. Review of Architecture, Islam, and Identity in West Africa: Lessons from Larabanga by Michelle Apotsos". Caa.reviews. doi:10.3202/caa.reviews.2018.59. ProQuest 2020305853.

- ^ a b Cantone, Cleo (2006). "A Mosque in a Mosque: Some Observations on the Rue Blanchot Mosque in Dakar & Its Relation to Other Mosques in the Colonial Period (Une mosquée dans une mosquée. Quelques observations sur la mosquée de la rue Blanchot à Dakar et ses relations avec les autres mosquées pendant la période coloniale)". Cahiers d'Études Africaines. 46 (182): 363–387. doi:10.4000/etudesafricaines.15253. JSTOR 4393580.