Arrajan

ارجان | |

| Alternative name | Arjān, Argān, Weh az Amid Kavād, Bih az Āmid-i Kavādh, Wām-Qubādh, Rām-Qubādh, Bizām-Qubādh, Birām-Qubādh, Āmid-Qubādh, Abar-Qubādh |

|---|---|

| Location | Argan District (Kavad-Khwarrah), Pars, Sasanian Empire (modern-day Arghūn (ارغون) area, Behbahan County, Khuzestan province, Iran) |

| Coordinates | 30°39′14″N 50°16′29″E / 30.65389°N 50.27472°E |

| Type | settlement |

| Length | 1.5 km (0.93 mi) |

| Width | 2.5 km (1.6 mi) |

| History | |

| Material | Ashlar |

| Founded | early 6th century |

| Abandoned | 1058 AD |

| Cultures | Iranian/Roman |

| Site notes | |

| Condition | Ruined |

| Public access | Yes |

Arrajan (Argan) was a medieval Persian city located between Fars and Khuzestan, which was settled since the civilisation of Elam in the second millennium BCE, and was important from the Sasanian Empire until the 11th century as the capital of a province of the same name that corresponds to present-day Behbahan in Khuzestan province, Iran.[1][1]

The city was refounded by the Sasanian emperor Kavad I and continued to develop in the Islamic period. Having fertile soil and supplies of water and integrated into a major road system, this small province flourished and reached its peak in the 10th century. It declined by the 11th century as a result of an earthquake and military conflicts.[1]

History

[edit]The archaeological site of Arrajan covers an area of about 3.75 km2 (1.45 sq mi), with only scattered traces of buildings, walls, a castle, a qanat, a dam, and a bridge across the nearby Marun river.[1] Arjan, or Argan / Arigan is the ancient name of Behbahan. Which belongs to the Elamite / Khuzi period, in Iran.in 1982 there was a big discovery in the ruins of the ancient Arjan a bronze coffin discovered inside there was some preciously ancient artifacts. The remains of the city ruins is located on both sides of the Maroon River a site of about 500 hectares.

Sasanian period

[edit]According to Islamic sources, the city was established by the Sasanian king Kavadh I (r. 484, 488–497 and 499–531), who in his third period of his rule launched a campaign as part of the Anastasian War against northern Roman Mesopotamia, and deported 80,000 prisoners from Amida, Theodosiopolis, and possibly Martyropolis to Pars and Khuzestan provinces, some of whom are thought to have built the city of Arrajan.[1] The people of the Amida region were experts in linen production, and Arrajan quickly became a center of this product.[1][2]

Kavadh allegedly renamed the city as Weh-az-Amid Kavād (Middle Persian: wyḥcʾmtˈ kwʾtˈ; literally "Better than Amida, Kavadh [built this]") or Bih-az-Āmid-i Kavād (Persian: به از آمد کواد). This name is Arabized in medieval Islamic sources (including coins) as Wāmqubādh (وامقباذ), Bizāmqubādh (بزامقباذ), Rām-Qubādh (رامقباذ), Birām-Qubādh (برامقباذ), and Āmid-Qubādh (آمدقباذ). It is also erroneously recorded as Abar-Qubādh (أبرقباذ) and Abaz-Qubādh (أبزقباذ) in Arabic sources. The more common name Arrajān comes from an older town that was populated before the foundation of this new one. The name of Arrajan (Argān) can be found on a Sasanian clay bulla.[1][3][4][2] The Pahlavi abbreviation WHYC found on Sasanian and Arab-Sasanian coins is considered by some to refer to Arrajan. However, it is more likely that the abbreviation refers to two places; it refers to Arrajan in the coins of Kavad I, and refers to a place in al-Mada'in in later coins; because it is unlikely that a small settlement continued to mint coins for all of these kings.[5][6]

-

Ruins of Arrajan's bridge

-

Ruins of walls

-

A stone-paved Roman road

Other Sasanian cities located in the Arrajan province and recorded by Islamic sources include:[1]

- Jannāba (جنابة) – near Bandar Ganaveh on the Persian Gulf), recorded only in Islamic sources

- Rīshahr (ريشهر) – on the northern bank of the Hendijan river

- Sīnīz (سينيز) – about 23 km southeast of Bandar Daylam on the Persian Gulf, recorded only in Islamic sources

-

Siniz's coast

-

Rishehr's coast

There are remains of Sasanian buildings in Patāva (a bridge over Khersan river) and Chahartaqi of Kheyrabad.[1]

-

Chahartaqi of Kheyrabad, an early example of chahartaqi

-

The Chahartaqi of Kheyrabad and the nearby Sasanian-era bridge

Islamic period

[edit]

Arrajan's development continued even after the Islamic conquest of Persia, reaching its peak in the 11th century.[1]

Medieval Islamic sources provide details about the city in that period, depicting it as a large and beautiful city.[1] It featured six gates, an administrative building, and a citadel. The Great Mosque was located roughly at the city's center, and the bazaar was located nearby. Ashlar was used in the construction of the buildings. The houses featured cool apartments below ground level, as the city featured a "hot but tolerable" climate. There were subterranean canals supplying water to all houses in the town. Two bridges were constructed across the Kordestan river (Tāb [طاب]) nearby.[1]

Islamic sources mention 47 place names and/or districts located in the Arrajan province, including Jūma (جومة) (capital of the Bilād-Shābūr [بلاد شابور] district), Junbadh-Mallaghān (جنبذ ملغان), and Mahrūbān (مهروبان).[1]

As a province, Arrajan, which is recorded as Kūra Qubāḏ-kurra or Kūra Qubāḏ in New Persian, was situated in an important position; it was integrated into a road system that connected Mesopotamia, Susa, Shiraz, Isfahan, and the ports of Mahruban and Basra at Persian Gulf to each other.[1]

Arrajan's economy was based on agricultural production and trade with India, the Far East, and Iraq through the ports of Jannāba, Sīnīz, and Mahrūbān. Exporting goods included various cloths, dates, date syrup, grapes, grape syrup, olives, olive oil, soap, cactus figs, corn, nuts, oranges, and lemons.[1]

Decline

[edit]Arrajan's decline began during Buyid period. In 1052, the sons of the Buyid Abu Kalijar fought against each other for possession of Arrajan city and it changed hands several times between 1053 and 1057. The number of male inhabitants was allegedly 20,000 in 1052 AD.[1]

In 1085, Arrajan was destroyed by an earthquake and never recovered; the new settlement, Behbahan, later arose nearby.[1]

The activities of the Nizari Ismailis in the region, who launched raids from the nearby strongholds of Qal'at al-Jiss (قلعة الجص), Qal'at Halādhān (Dez Kelāt, دز کلات), and Qal'at al-Nazir (قلعة الناظر) further harmed Arrajan and Juma. They eventually captured Arrajan,[1][4] but were eventually repulsed during Muhammad Tapar's anti-Nizari campaign.

As the Arrajan city declines, the province name "Arrajan" also disappears. Mahrūbān later became the most important center of the maritime trade, marginalizing Jannāba.[1]

The Arjan Bowl

[edit]

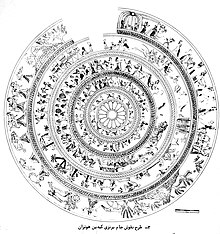

In 1982, the remains of a tomb belonging to the second millennium BC were discovered near the Arjan ancient site, which opened a new chapter in the archeology of this historical site and the region. The tomb contained a large bronze coffin. Along with the coffin were found a golden ring, ninety-eight golden buttons, ten cylindrical vessels, a dagger, a silver bar, a bronze tray with various images. it is called Arjan Bowl or Hotran Korlosh It is more than three thousand years old. Arjan tray drawings include 5 painting circles in its center a sixteen-pointed flower (similar to a sunflower and a type of chrysanthemum). This flower symbolizes the sun and the spinning wheel or wheel of destiny. A row of lions, and cattle, and birds are associated with various rituals, and seven circles or rings represent the sacred number 7. The number 7 is sacred in Judaism and many other religions. The origin of this sanctity is not clear, but like many symbols of famous religions it has a history in ancient primitives religions. The logo of the Iranian Olympic Iran at the 2020 Summer Olympics is the Arjan tray.[7] [2] .[]

References

[edit]- Arjan of the Elamite era, the armlet dates back to the Neo-Elamite period [6]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Gaube, Heinz. "ARRAJĀN". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

- ^ a b A. Shapur Shahbazi, Erich Kettenhofen, John R. Perry, "Deportations", Encyclopædia Iranica, VII/3, pp. 297-312 (accessed on 30 December 2012).

- ^ Frye, Richard Nelson (1984). The History of Ancient Iran. C.H.Beck. p. 333. ISBN 9783406093975.

- ^ a b Houtsma, Martijn Theodoor; Arnold, Sir Thomas Walker; Basset, René; Hartmann, Richard; Wensinck, Arent Jan; Heffening, Willi; Gibb, Sir Hamilton Alexander Rosskeen (1913). The Encyclopaedia of Islām: A Dictionary of the Geography, Ethnography and Biography of the Muhammadan Peoples. E.J. Brill Limited. p. 460.

- ^ Tyler-Smith, Susan (2004). "The Kavād Hoard". The Numismatic Chronicle. 164: 308–312. ISSN 0078-2696. JSTOR 42666299.

- ^ Album, Stephen; Goodwin, Tony (2002). Sylloge of Islamic coins in the Ashmolean: The pre-reform coinage of the early Islamic period. Ashmolean Museum. p. 67. ISBN 9781854441737.

- ^ M, Mohammad Ajam. "ARJĀN". Parssea. Retrieved 29 Jul 2021.