Webster–Ashburton Treaty

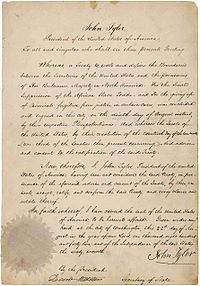

Webster–Ashburton Treaty document of August 9, 1842 | |

| Type | Bilateral treaty |

|---|---|

| Signed | 9 August 1842 |

| Location | Washington, DC, United States |

| Negotiators |

|

| Original signatories | |

| Ratifiers |

|

The Webster–Ashburton Treaty, signed August 9, 1842, was a treaty that resolved several border issues between the United States and the British North American colonies (the region that later became the Dominion of Canada). Negotiated in the US federal capital city of Washington, DC, it was signed August 9, 1842, under the new administration of US President John Tyler, who as the former vice president, had just recently succeeded and became chief executive upon the unexpected death of his running mate and predecessor, William Henry Harrison, who had only served a single month in office. The Daniel Webster–Lord Ashburton negotiations and new drawn-up 1842 treaty resolved many of the issues of the recent border conflicts and skirmishes between Americans and New Brunswickers in the Aroostook War of 1838–1839. It arose from disputes and controversies over the vague indefinite terms and text of the old peace agreement of the Treaty of Paris of 1783, which ended the American Revolutionary War.

The provisions of the 1842 treaty between Britain and the United States included:

- The settlement of the location of the Maine–New Brunswick international border,[1] which was the primary cause of the Aroostook War.

- Establishment of the international border between Lake Superior and the Lake of the Woods, originally defined in the Treaty of Paris in 1783

- Reaffirmation of the location of the border (at the 49th parallel) in the westward frontier up to the far western Rocky Mountains defined in the previous Treaty of 1818

- Definition of seven crimes subject to extradition

- Agreement that the two parties would share use of the Great Lakes

- Agreement that there should be a final end to the slave trade on the high seas

The treaty also retroactively confirmed the southern boundary of the Province of Quebec that land surveyors John Collins and Thomas Valentine had marked with stone monuments in 1771–1773. The treaty intended that the international border be fixed at the 45 degrees north parallel of latitude, but the border is in some places nearly 0.8 km (1⁄2 mi) north of the 45th parallel. The treaty was signed by US Secretary of State Daniel Webster, and British diplomat Alexander Baring, 1st Baron Ashburton.[2]

In the East

[edit]

An arbitration of various border issues in the East before King William I of the Netherlands in 1831 had failed to yield a binding decision.[3]

The Treaty of Paris had established the 45th parallel as part of the northern boundary of modern-day New York and Vermont. Most of that portion of the boundary had previously been surveyed in the early 1770s, but the survey line was inaccurate. Since "Fort Blunder"—an unnamed U.S. fort in what is now part of northeastern New York—had been constructed north of the actual 45th parallel, the United States wanted to follow the old survey line, and the Webster–Ashburton treaty incorporated this change, leaving the half-finished fort on U.S. soil. Following the signing of the treaty, the U.S. resumed construction on the site. The new project replaced the aborted 1812-era construction with a massive third-system masonry fortification known as Fort Montgomery.[2]

This treaty marked the end of local confrontations between lumberjacks (known as the Aroostook War) along the Maine border with the British colonies of Lower Canada (which later became Quebec) and New Brunswick. The newly agreed border divided the disputed territory between the two nations. The British were assigned the Halifax–Quebec road route, which their military desired because Lower Canada had no other connection in winter to New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. The treaty adjusted portions of the border to give the United States a little more land to the north. It also resolved issues that had led to the Indian Stream dispute as well as the Caroline Affair. The Indian Stream area was assigned to the United States. The Webster–Ashburton Treaty failed to clarify ownership of Machias Seal Island and nearby North Rock, which remain in dispute.[2] Additionally, the signing of the treaty put an end to several building improvements planned for Upper Canadian defense forts such as Fort Malden in Amherstburg, which the British government later abandoned, as they no longer served a defensive purpose.

In the West

[edit]

The border between Lake Superior and the Lake of the Woods in the Great Lakes region needed clarification because the faulty Mitchell Map used in the negotiations for the Treaty of Paris (1783) was inadequate to define the border according to the terms of that British-American treaty. Ambiguity in the map and treaty resulted in Minnesota's Arrowhead region being disputed between the two nations years later, and previous negotiations had not resolved the question. The treaty had the border pass through Long Lake, but did not state that lake's location.[4] However, the map showed the lake flowing into Lake Superior near Isle Royale, which is consistent with the Pigeon River route.

The British, however, had previously taken the position that the border should leave Lake Superior at Fond du Lac (the "head of the lake") in modern Duluth, Minnesota, proceed up the Saint Louis and Embarrass rivers, across the height of land, and down Pike River and Lake Vermilion to the Rainy River.[5][6]

To counter this western route, the U.S. side advocated for an eastern route, used by early French explorer Jacques de Noyon in 1688, and the later a well-used fur traders' route after 1802. This way headed north from the lake at the site of Fort William up the Kaministiquia and Dog Rivers to Cold Water Lake, crossed the divide by Prairie Portage to Height of Land Lake, then went west by way of the Savanne, Pickerel, and Maligne rivers to Lake La Croix, where it joined the present international border.[7]

The Mitchell map had shown both of those routes, and also showed the "Long Lake" route between them.[8] Long Lake was thought to be the Pigeon River (despite the absence of a lake at its mouth).[a]

The traditional traders' route left the lake at Grand Portage and went overland to the Pigeon, up that river and a tributary across the Height of Land Portage, and thence down tributaries of the Rainy River to Lac La Croix, Rainy Lake and River, and Lake of the Woods. This is finally the route the treaty designated as the border.[9]

The treaty clarified the channel that the border would follow between Lake Huron and Lake Superior, awarding Sugar Island to the U.S.

Another clarification made in this treaty resulted in clarifying the anomaly of the Northwest Angle. Again, due to errors on the Mitchell Map, Treaty of Paris reads "... through the Lake of the Woods to the most northwesternmost point thereof, and from thence on a due west course to the river Mississippi ..." In fact, a course due west from the Lake of the Woods never intersects the Mississippi. The Anglo-American Convention of 1818 defined the boundary about Lake of the Woods to the Rocky Mountains.[citation needed]

This 1842 treaty reaffirmed the border and further defined it by modifying the border definition to instead read as:

... at the Chaudiere Falls, from which the Commissioners traced the line to the most northwestern point of the Lake of the Woods, thence, along the said line to the said most northwestern point, being in latitude 49°23′55″ north, and in longitude 95°14′38″ west from the Observatory at Greenwich; thence, according to existing treaties, due south to its intersection with the 49th parallel of north latitude, and along that parallel to the Rocky Mountains ...

The Webster–Ashburton Treaty failed to deal with the Oregon question, although the issue was discussed in negotiations.

Other issues

[edit]Article 10 of the Webster–Ashburton Treaty identified seven crimes subject to extradition: "murder, or assault with intent to commit murder, or piracy, or arson, or robbery, or forgery, or the utterance of forged paper." It did not include slave revolt or mutiny. In addition, the United States did not press for the return or extradition of an estimated 12,000 fugitive slaves who had fled the U.S. going north and reached British territory in Canada.[10]

While agreeing to call for a final end to the slave trade on the high seas, Secretary Webster and Lord Ashburton agreed to pass over the Creole case of 1841 in the Caribbean Sea, which was then in contention. In November 1841, a slave revolt on the American merchantman brig Creole, part of the coastwise slave trade, had forced the ship to call at the port of Nassau in the Bahamas. British / Bahamian colonial officials eventually emancipated all 128 slaves who chose to stay in Nassau, as Britain had already abolished slavery in its colonies, effective seven years before in 1834.[10] The United States initially demanded return of the slaves and then compensation. A settlement was made in 1855 as part of a much larger claims treaty of 1853, which covered claims by both nations dating back to 1814.

The treaty laid down minimum levels of joint anti-slaving naval activity off the West African coast by warship squadrons of both the United States Navy and the British Royal Navy. It formalised levels of co-operation that had briefly existed in 1820 and 1821. It fell short of providing greater co-operation in suppression of the slave trade; there was, for instance, no mutual right for the two countries to inspect vessels flying each other's flag even when the United States flag / colours were being flown fraudulently by a slaver from a third country. The treaty, therefore, had only a minimal effect for the time in reducing the trans-Atlantic slave trade.[11]

Results

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2016) |

As a result of the Webster–Ashburton Treaty of 1842, the United States ceded 5,000 square miles (13,000 km2) of disputed territory to the British / Canadians along the American-claimed northern Maine border, including the Halifax–Quebec Route, but kept 7,000 square miles (18,000 km2) of the disputed wilderness.[12] In addition, the United States received 6,500 square miles (17,000 km2) in compensation with the compromise of further west on the Minnesota–Canada border, which included the Mesabi Range of mountains, west of Lake Superior.[12] Shortly after the advice and consent process with the ratification of the Webster–Ashburton Treaty by the United States Senate (upper chamber of the Congress of the United States) at the old smaller United States Capitol in Washington), the native Ojibwa nations around about the south shore of Lake Superior, ceded land to the United States in the subsequent Treaty of La Pointe. However, the news of the ratification of the British-American international treaty did not reach either of the two parties further west, involved in negotiating the land cession. The Grand Portage Band of natives was mistakenly omitted from the Ojibwe treaty council. In addition, the Grand Portage Band was misinformed on the details of the old Treaty of Paris of 1783, 59 years earlier; they believed that the border passed through the center of Lake Superior to the Saint Louis River, placing both Isle Royale and their band to be located in British territory. The Treaty of Paris back then specifically noted in its text, that Isle Royale was in the territories of the new United States to the south. Consequently, because of this misunderstanding / misinterpretation, a later Isle Royale Agreement was signed between the United States and the Grand Portage Band, two years later in 1844 as an adhesion / amendment to the Treaty of La Pointe, with other Ojibwa tribes reaffirming the treaty.

Ten months of negotiations for the 1842 Treaty were held largely at the Ashburton House, and also home of the British legation (future elevated / renamed embassy), facing on historic prominent Lafayette Square, two blocks north of the White House in the federal national capital city of Washington, D.C.. The townhouse has since been designated a U.S. National Historic Landmark, on the lists maintained by the National Park Service of the United States Department of the Interior.

To make the controversial treaty more palatable and popular in the United States, Secretary of State Webster released a map of the Maine–Canada border, taken from the beginning national archives and files at the United States Department of State offices, which he claimed that earlier famous American founding father and negotiator / diplomat of Benjamin Franklin (c.1705/1706-1790), of Pennsylvania had drawn of the territory. It showed contested areas of that time during the original 1783 Paris Treaty negotiations largely resolved in favor of the United States.

See also

[edit]- List of treaties

- History of Canada–United States border agreements through 1908

- Timeline of United States diplomatic history

- Estcourt Station, Maine

- Slave Trade Acts

- Slavery in the United States

- United Kingdom–United States relations

- Aroostook War

- New England

- History of New England

- Maine

- History of Maine

- Massachusetts

- History of Massachusetts

- Massachusetts Bay Colony

- New Brunswick

- History of New Brunswick

- Quebec

- History of Quebec

- Nova Scotia

- History of Nova Scotia

- Canada

- History of Canada

Notes

[edit]- ^ On the La Vérendrye Map, series of lakes are shown, of which "Lac de Sesakinaga" (Saganaga Lake), a Height of Land, "Lac Plat", "Lac Long" and Grand Portage are shown in relative equidistance from each other, thus alluding to Mountain Lake or Arrow Lake as "Lac Long", all long lakes on the Pigeon River route.[citation needed]

References

[edit]- ^ Charles M. Wiltse, "Daniel Webster and the British Experience." Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society Vol. 85. (1973) pp 58–77. online Archived August 2, 2020, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b c Carroll (2001).

- ^ "Decision of the Arbiter, January 1831". Archived from the original on December 21, 2016. Retrieved June 26, 2017.

- ^ Lass (1980), pp. 1, 11, 37.

- ^ Lass (1980), pp. 37–39, 49.

- ^ Vogel & Stanley (1992), pp. E-12, E-13.

- ^ Lass (1980), pp. 37–39, 44.

- ^ Lass (1980), p. 37.

- ^ "Webster–Ashburton Treaty, Art. 2". Yale Law School. 1842. Archived from the original on August 25, 2006. Retrieved September 18, 2008.

- ^ a b Jones (1975), pp. 28–50.

- ^ Grindal 2016, p. 1144.

- ^ a b Kennedy, Bailey & Cohen (2006), pp. 374, 375.

Works cited

[edit]- Carroll, Francis M. (2001). A Good and Wise Measure: The Search for the Canadian–American Boundary, 1783–1842. University of Toronto Press.

- Grindal, Peter (2016). Opposing the Slavers. The Royal Navy's Campaign against the Atlantic Slave Trade (Kindle ed.). London: I.B.Tauris & Co. Ltd. ISBN 978-0-85773-938-4.

- Jones, Howard (March 1975). "The Peculiar Institution and National Honor: The Case of the Creole Slave Revolt". Civil War History. 21 (1): 28–50. doi:10.1353/cwh.1975.0036.

- Kennedy, David M.; Bailey, Thomas Andrew & Cohen, Lizabeth (2006). The American Pageant (13th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0618479279. OCLC 846067545.

- Lass, William E. (1980). Minnesota's Boundary with Canada. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society. ISBN 0-87351-153-0.

- Vogel, Robert C. & Stanley, David G. (1992). "Portage Trails in Minnesota, 1630s–1870s" (PDF) (Multiple Property Documentation Form). National Park Service. Archived from the original on November 19, 2018. Retrieved May 13, 2008.

Further reading

[edit]- Carroll, Francis M. (March 1997). "The Passionate Canadians: The Historical Debate about the Eastern Canadian–American Boundary". New England Quarterly. 70 (1): 83–101. doi:10.2307/366528. JSTOR 366528.

- ——— (2001). A Good and Wise Measure: The Search for the Canadian–American Boundary, 1783–1842. University of Toronto Press. (the standard scholarly history)

- ——— (2003). "Drawing the Line". Beaver. 83 (4): 19–25.

- Corey, Albert B. (1941). The Crisis of 1830–1842 in Canadian–American Relations.

- Jones, Howard (December 1975). "Anglophobia and the Aroostook War". New England Quarterly. 48 (4): 519–539. doi:10.2307/364636. JSTOR 364636.

- ——— (1977). To the Webster–Ashburton Treaty: A Study in Anglo-American Relations, 1783–1843.

- Jones, Wilbur Devereux (February 1956). "The Influence of Slavery on the Webster–Ashburton Negotiations". Journal of Southern History. 22 (1): 48–58. doi:10.2307/2955259. JSTOR 2955259.

- Lacroix, Patrick (2016). "Choosing Peace and Order: National Security and Sovereignty in a North American Borderland, 1837–42". International History Review. 38 (5): 943–960. doi:10.1080/07075332.2015.1070892. S2CID 155365033. Archived from the original on July 26, 2022. Retrieved July 26, 2022.

- LeDuc, Thomas (December 1964). "The Webster–Ashburton Treaty and the Minnesota Iron Ranges". Journal of American History. 51 (3): 476–481. doi:10.2307/1894897. JSTOR 1894897. (shows the value of the iron range was not known when the treaty was drawn)

- Merk, Frederick (December 1956). "The Oregon Question in the Webster–Ashburton Negotiations". Mississippi Valley Historical Review. 43 (3): 379–404. doi:10.2307/1893529. JSTOR 1893529.

- Remini, Robert (1997). Daniel Webster. pp. 535–64. ISBN 978-0393045529.

- The Maine Council (1904). Historical Sketch Roster of Commissioned Officers and Enlisted Men Called Into Service for the Protection of the Northeastern Frontier of Maine from February to May 1839. Augusta, ME: Kennebec Journal Print. pp. 4–5. Retrieved October 15, 2007 – via Internet Archive.

aroostook war.

External links

[edit]- Text of the Webster–Ashburton Treaty (The Avalon Project at Yale Law School)

- Webster–Ashburton Treaty (U.S. Department of State)

- Franklin Map Possibly Forged

- Canada–United States treaties

- United Kingdom–United States treaties

- 1842 treaties

- Boundary treaties

- Canada–United States border

- History of the foreign relations of the United States

- Legal history of Canada

- Aroostook War

- North Maine Woods

- 1842 in Canada

- 1842 in the United States

- Treaties of the United Kingdom (1801–1922)

- Daniel Webster

- Eponymous treaties