Watch on the Rhine

| Watch on the Rhine | |

|---|---|

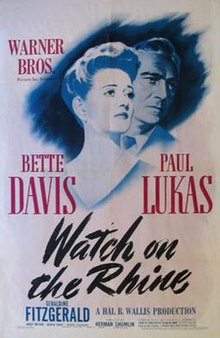

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Herman Shumlin |

| Screenplay by | Dashiell Hammett |

| Based on | Watch on the Rhine 1941 play by Lillian Hellman |

| Produced by | Hal B. Wallis |

| Starring | Bette Davis Paul Lukas Geraldine Fitzgerald Lucile Watson Beulah Bondi George Coulouris |

| Cinematography | Merritt B. Gerstad Hal Mohr |

| Edited by | Rudi Fehr |

| Music by | |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. |

Release date |

|

Running time | 114 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $1,099,000[1] |

| Box office | $2.5 million (US rentals)[2] or $3,392,000[1] |

Watch on the Rhine is a 1943 American drama film directed by Herman Shumlin and starring Bette Davis and Paul Lukas. The screenplay by Dashiell Hammett is based on the 1941 play Watch on the Rhine by Lillian Hellman. Watch on the Rhine was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Picture and Paul Lukas won the Academy Award for Best Actor for his performance as Kurt Muller, a German-born anti-fascist in this film.[3]

Plot

[edit]In 1940, German engineer Kurt Muller, his American wife Sara, and their children Joshua, Babette, and Bodo cross the Mexican border into the United States to visit Sara's brother David Farrelly and their mother Fanny in Washington, D.C. For the past 17 years, the Muller family has lived in Europe, where Kurt responded to the rise of Nazism by engaging in anti-fascist activities. Sara tells her family they are seeking peaceful sanctuary on American soil, but their quest is threatened by the presence of house guest Teck de Brancovis, an opportunistic Romanian count who has been conspiring with the German Embassy. Teck, married to the younger Marthe, tries to force her to learn more about the Mullers. She and David are attracted to each other and she finds her husband's politics horrendous.

Teck searches the Mullers' room and discovers a gun and money intended to finance underground operations in Germany. Shortly after, the Mullers learn that resistance worker Max Freidank has been arrested. Because Max once rescued Kurt from the Gestapo, Kurt plans to return to Germany to assist him and those arrested with him. Aware that Kurt will be in great danger if the Nazis discover he is returning to Germany, Teck demands $10,000 ($220,000 today) to keep silent. After considerable bargaining, Kurt kills him, having concluded that Teck cannot be trusted. Realizing the dangers Kurt faces, Fanny and David agree to help him return.

Time passes, and when the Mullers fail to hear from Kurt, Joshua announces he plans to search for his father as soon as he turns 18. Although distraught by the possibility of losing her son as well as her husband, Sara resolves to be brave when the time comes for Joshua to leave.

Cast

[edit]- Bette Davis as Sara Muller

- Paul Lukas as Kurt Muller

- Lucile Watson as Mrs. Fanny Farrelly

- Geraldine Fitzgerald as Countess Marthe de Brancovis

- George Coulouris as Count Teck de Brancovis

- Beulah Bondi as Anise

- Donald Woods as David Farrelly

- Donald Buka as Joshua Muller

- Janis Wilson as Babette Muller

- Hal Weilandgruber as Bodo Muller

- Henry Daniell as Baron Phili von Ramme

- Kurt Katch as Blecher

- Clarence Muse as Horace

- Mary Young as Mrs. Mellie Sewell

- Anthony Caruso as Italian Man on Train

Production

[edit]The Lillian Hellman play had enjoyed a respectable run of 378 performances on Broadway.[4] Feeling its focus on patriotism would make it an ideal and prestigious propaganda film at the height of World War II,[5] Jack L. Warner paid $150,000 for the screen rights in 1941.[6][7][8][9][10] The play's producer Herman Shumlin was hired as director, while many of the actors from the play reprised their role in the film.

Because Bette Davis was involved with Now, Voyager, producer Hal B. Wallis began searching for another actress for the role of Sara Muller while Hellman's lover Dashiell Hammett began writing the screenplay at their farm in Pleasantville, New York. Irene Dunne liked the material but felt the role was too small, and Margaret Sullavan expressed no interest whatsoever. Edna Best, Rosemary DeCamp, and Helen Hayes also were considered.

For the role of Kurt Muller, Wallis wanted Charles Boyer. He, however, felt his French accent was wrong for the character,[9] so the producer decided to cast Paul Lukas, who had originated the role on Broadway and had been honored by The Drama League for his performance.[8]

Paul Henreid later said Jack Warner offered him the lead but turned it down because he did not want to be typecast, and felt that it was based on a "contrived play, in no way up to Elmer Rice's Flight to the West. My original contract stipulated that I always get the girl and I used that as an excuse to get out of the movie."[11]

Meanwhile, Hammett was sidelined by an injured back, and by the time he was ready to resume work on the script, Davis was close to completing her work in Now, Voyager. Wallis sent Davis, a staunch supporter of Franklin D. Roosevelt and a fierce opponent of the Nazi Party, the screenplay-in-progress, and she immediately accepted the offer.

With Davis cast as Sara, Wallis encouraged Hammett to embellish what essentially was a secondary role to make it worthy of the leading lady's status as a star,[9] and to open the story by adding scenes outside the Farrelly living room, which had been the sole setting on stage.[8]

The Production Code Administration was concerned that Kurt Muller escaped prosecution for his murder of Teck de Brancovis, and the Hays Office suggested it be established Kurt was killed by the Nazis at the end of the film in order to show he paid for his crime. Hellman objected,[12] the studio agreed Kurt had been justified in shooting Teck, and the scene remained.[7] In his afterword to the April 25, 2020 airing of Watch on the Rhine on TCM, Dave Karger describes this controversy in more detail. According to Karger's script, Joe Breen demanded a new scene in which Muller suffered the consequences of his actions, but Lukas did not show up for the filming. The censor insisted that Muller could not be allowed to get away with murder, even of a Nazi, so the last scene of the film, between Sara and her son, Joshua, was added. Many months have passed without word from Muller, strongly suggesting that he has been captured and/or killed.

Filming began on June 9, 1942, and did not go smoothly. Beginning only a week after Now, Voyager had ended production, Davis was working without a substantial vacation and was on edge. As a result, she immediately clashed with Herman Shumlin, who had directed the play but had no experience in film, and she tended to ignore his suggestions.

Her emotional overacting prompted Wallis to send Shumlin numerous memos urging the director to tone down her performance.[9] Shumlin threatened to quit because he was unhappy with cinematographer Merritt B. Gerstad, who eventually was replaced by Hal Mohr in order to appease the director.[8] Meanwhile, Davis also was at odds with Lucile Watson who was reprising the role of the mother she had portrayed on stage, because Watson was a Republican whose political views sharply contrasted with those of the Democratic Davis. She and Lukas, however, got along quite well.[9]

Several exterior scenes shot on location in Washington were cut from the film before its release due to wartime restrictions on the filming of government buildings. Other locations included the Warner Bros. Ranch in Burbank, Busch Gardens in Pasadena, Los Angeles Union Station, and the Graves Mansion in San Marino, California.[6]

When Wallis announced he was giving Davis top billing, she argued it was ridiculous to do so given hers was a supporting role. The studio's publicity department argued it was her name that would attract an audience, and despite her resistance, the film's credits and all promotional materials listed her first.[9]

Davis and Lukas reprised their roles for a radio adaptation that aired in the January 10, 1944 broadcast of The Screen Guild Theater.

Box office

[edit]According to Warner Bros records the film earned $2,149,000 domestically and $1,243,000 foreign.[1]

Critical reception

[edit]Bosley Crowther of The New York Times called Watch on the Rhine "a distinguished film — a film full of sense, power and beauty" and added, "Its sense resides firmly in its facing one of civilization's most tragic ironies, its power derives from the sureness with which it tells a mordant tale and its beauty lies in its disclosures of human courage and dignity. It is meager praise to call it one of the fine adult films of these times." He continued, "Miss Hellman's play tends to be somewhat static in its early stretches on the screen. With much of the action confined to one room in the American home, development depends largely on dialogue — which is dangerous in films. But the prose of Miss Hellman is so lucid, her characters so surely conceived and Mr. Shumlin has directed for such fine tension in this his first effort for the screen that movement is not essential. The characters propel themselves." In conclusion, he said, "An ending has been given the picture which advances the story a few months and shows the wife preparing to let her older son follow his father back to Europe. This is dramatically superfluous, but the spirit is good in these times. And it adds just that much more heroism to a fine, sincere, outspoken film."[13]

Variety called it "a distinguished picture...even better than its powerful original stage version. It expresses the same urgent theme, but with broader sweep and in more affecting terms of personal emotion. The film more than retains the vital theme of the original play. It actually carries the theme further and deeper, and it does so with passionate conviction and enormous skill...Just as he was in the play, Paul Lukas is the outstanding star of the film. Anything his part may have lost in the transfer of key lines to Bette Davis is offset by the projective value of the camera for closeups. His portrayal of the heroic German has the same quiet strength and the slowly gathering force that it had on the stage, but it now seems even better defined and carefully detailed, and it has much more vitality. In the lesser starring part of the wife Davis gives a performance of genuine distinction."[14]

Davis stated in a 1971 interview with Dick Cavett that she played the role of the wife for 'name value' because the studio did not consider the film a good financial risk and that her name above the credits would draw audiences. Davis gladly took the secondary role because she felt the story was so important, and that Hellman's writing was "super brilliant".[15]

The National Board of Review of Motion Pictures observed "Paul Lukas here has a chance to be indisputably the fine actor he always has shown plenty signs of being. Bette Davis subdues herself to a secondary role almost with an air of gratitude for being able to at last be uncomplicatedly decent and admirable. It is not a very colorful performance, but quiet loyalty and restrained heroism do not furnish many outlets for histrionic show, and Miss Davis is artist enough not to throw any extra bits of it to prove she is one of the stars."[8]

Awards and nominations

[edit]The film won the New York Film Critics Circle Award for Best Picture.

It was also nominated for the Academy Award for Best Picture.

Paul Lukas won the Academy Award for Best Actor, the Golden Globe Award for Best Actor – Motion Picture Drama (the first time the award was presented), and the New York Film Critics Circle Award for Best Actor.

Lucile Watson was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress but lost to Katina Paxinou in For Whom the Bell Tolls. Dashiell Hammett was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Writing (Adapted Screenplay) but lost to the trio of Philip G. Epstein, Julius J. Epstein, and Howard Koch, who won for the work in Casablanca.

Home media

[edit]On April 1, 2008, Warner Home Video released the film as part of the box set The Bette Davis Collection, Volume 3.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Warner Bros financial information in The William Schaefer Ledger. See Appendix 1, Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, (1995) 15:sup1, 1-31 p 24 DOI: 10.1080/01439689508604551

- ^ Variety (8 March 2018). "Variety (January 1944)". New York, NY: Variety Publishing Company – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "The 16th Academy Awards (1944) Nominees and Winners". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS). Archived from the original on March 21, 2016. Retrieved August 27, 2013.

- ^ "Watch on the Rhine". Internet Broadway Database. Retrieved 2015-08-09.

- ^ Dick, Bernard F. (May 21, 2004). Hal Wallis, Producer to the Stars. University of Kentucky Press. p. 76. ISBN 978-0813123172.

- ^ a b "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved 2022-02-21.

- ^ a b "Watch on the Rhine (1943)". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved 2023-12-14.

- ^ a b c d e Stine, Whitney; Davis, Bette (May 1, 1974). Mother Goddam: The Story of the Career of Bette Davis. New York: Hawthorn Books. pp. 170–172. ISBN 978-0801551840.

- ^ a b c d e f Higham, Charles (October 1, 1981). Bette: The Life of Bette Davis. New York: Macmillan Publishing Company. pp. 164–166. ISBN 978-0025515000.

- ^ "Film Rights $ Up and Up; Hollywood Gets Taken But Presitige Pix Pay." Billboard 55:49 (4 December 1943), 4.

- ^ Henreid, Paul; Fast, Julius (1984). Ladies man : an autobiography. St. Martin's Press. p. 166. ISBN 9780312463847.

- ^ "Watch on the Rhine (1943) - Herman Shumlin - film review". Retrieved 27 January 2017.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (August 28, 1943). "Movie Review: Watch on the Rhine". The New York Times.

- ^ "Review: 'Watch on the Rhine'". Variety. December 31, 1942. Retrieved 2023-12-14.

- ^ "The Dick Cavett Show: Season 6, Episode 40: Bette Davis". Internet Movie Database. November 18, 1971.

External links

[edit]- 1943 films

- American black-and-white films

- 1940s spy drama films

- American films based on plays

- American spy drama films

- American World War II propaganda films

- Films scored by Max Steiner

- Films scored by Hugo Friedhofer

- Films about the German Resistance

- Films based on works by Lillian Hellman

- Films featuring a Best Actor Academy Award–winning performance

- Films featuring a Best Drama Actor Golden Globe winning performance

- Films produced by Hal B. Wallis

- Films set in 1940

- Films set in country houses

- Films set in Washington, D.C.

- Films with screenplays by Dashiell Hammett

- 1943 drama films

- Warner Bros. films

- Films shot in Los Angeles

- Films shot in Washington, D.C.

- Films shot in Los Angeles County, California

- Films about anti-fascism

- Films about Nazi Germany

- 1940s English-language films

- English-language spy drama films

- English-language war films