Warringah Council

| Warringah Council New South Wales | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Location of Warringah Council, 1992–2016 | |||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 33°45′S 151°17′E / 33.750°S 151.283°E | ||||||||||||||

| Population | 140,741 (2011 census)[1] | ||||||||||||||

| • Density | 938.3/km2 (2,430/sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| Established | 7 March 1906 | ||||||||||||||

| Abolished | 12 May 2016 | ||||||||||||||

| Area | 150 km2 (57.9 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| Mayor | Michael Regan | ||||||||||||||

| Council seat | Warringah Civic Centre, Dee Why | ||||||||||||||

| Region | Metropolitan Sydney | ||||||||||||||

| State electorate(s) | |||||||||||||||

| Federal division(s) | |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Website | Warringah Council | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

Warringah Council was a local government area in the northern beaches region of Sydney, in the state of New South Wales, Australia. It was proclaimed on 7 March 1906 as the Warringah Shire Council, and became "Warringah Council" in 1993. In 1992, Pittwater Council was formed when the former A Riding of Warringah Shire voted to secede. From this point on until amalgamation, Warringah Council administered 152 square kilometres (59 sq mi) of land, including nine beaches and 14 kilometres (9 mi) of coastline. Prior to its abolition it contained 6,000 hectares (15,000 acres) of natural bushland and open space, with Narrabeen Lagoon marking Warringah's northern boundary and Manly Lagoon marking the southern boundary.

On 12 May 2016 the Minister for Local Government announced that Warringah Council, along with the Pittwater and Manly councils would be merged to establish the Northern Beaches Council with immediate effect.[2] The last mayor of Warringah Council was Cr Michael Regan, who was elected on 13 September 2008. The council seat was located in Warringah Civic Centre in Dee Why on Pittwater Road.

Suburbs and localities

[edit]

The following suburbs were located within Warringah Council:

- Allambie Heights

- Beacon Hill

- Belrose

- Brookvale

- Collaroy

- Collaroy Plateau

- Cottage Point

- Cromer

- Curl Curl

- Davidson

- Dee Why

- Duffys Forest

- Forestville

- Frenchs Forest

- Freshwater

- Ingleside

- Killarney Heights

- Manly Vale

- Narrabeen

- Narraweena

- North Balgowlah

- North Curl Curl

- North Manly

- Oxford Falls

- Queenscliff

- Terrey Hills

- Wheeler Heights

The following localities were located within Warringah Council:

- Akuna Bay

- Allambie

- Bantry Bay

- Bungaroo

- Collaroy Beach

- Cromer Heights

- Curl Curl Beach

- Dee Why Beach

- Fishermans Beach (Collaroy)

- Freshwater Beach

- Gooseberry Flat

- Long Reef Beach (Collaroy)

- Narrabeen Beach

- Narrabeen Peninsula

- North Curl Curl Beach

- North Narrabeen Beach

- Peach Trees

- Sorlie

- Wingala

Council

[edit]

Composition and election methods

[edit]| Term | Councillors | Wards | President/Mayor |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1906 (Temporary) | 5 | No wards | N/A |

| 1906–1914[3] | 6 (2 per ward) | A Riding B Riding C Riding |

Annual election by Councillors |

| 1914–1962[4] | 9 (3 per ward) | ||

| 1962–1968[5] | 15 (5 per ward) | ||

| 1968–1977 | 12 (4 per ward) | ||

| 1977–1992[6] | 12 (3 per ward) | A Riding B Riding C Riding D Riding | |

| 1992–1993[7] | 9 (3 per ward) | A Riding B Riding C Riding | |

| 1993–2008[7] | A Ward B Ward C Ward | ||

| 2008–2016 | 10 (3 per ward, 1 mayor) | Direct quadrennial election |

Final composition and election method

[edit]Warringah Council was composed of ten councillors, including the mayor, for a fixed four-year term of office. The mayor was directly elected (from 2008 to 2016) while the nine other Councillors were elected proportionally with three separate wards each electing three councillors. The last election was held on 8 September 2012, and the makeup of the council, including the mayor, was as follows when the council was dissolved.[8][9][10][11]

The last Council, elected in 2012, in order of election by ward, is as follows.

| Seat | Councillor | Party | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mayor[8] | Michael Regan | Your Warringah | Mayor 2008–2016;[12] Elected to Northern Beaches Council, 2017. | |

| A Ward[9] | Wayne Gobert OAM | Your Warringah | Elected 2012–2016. | |

| Vanessa Moskal | Your Warringah | Elected on Wayne Gobert's ticket, 2012–2016. | ||

| Vincent De Luca OAM | Independent | Elected 2008–2016; Elected to Northern Beaches Council, 2017. | ||

| B Ward[10] | Sue Heins | Your Warringah | Elected 2012–2016; Deputy Mayor 2013–2014; Elected to Northern Beaches Council, 2017. | |

| Bob Giltinan JP | Independent | Elected 2008–2016; Deputy Mayor 2012–2013.[13] | ||

| Pat Daley | Independent | Elected 2012–2016; Manly Councillor 2004–2008; Elected to Northern Beaches Council, 2017. | ||

| C Ward[11] | Roslyn Harrison | Your Warringah | Elected on Michael Regan's ticket, 2012–2016; Deputy Mayor 2015–2016; Elected to Northern Beaches Council, 2017. | |

| Duncan Kerr | Your Warringah | Elected on Michael Regan's ticket, 2012–2016. | ||

| Jose Menano-Pires | Independent | Elected 2012–2016; Deputy Mayor 2014–2015. | ||

History

[edit]The traditional Aboriginal owners of the land we now know as Warringah had mostly disappeared from this area within years of European settlement, mainly due to an outbreak of smallpox in 1789.[14]

The name Warringah was taken from the Aboriginal word for Middle Harbour, which was recorded as "Warrin ga", by the government surveyor, James Larmer, in 1832.[15]

Warringah had been in use for several years in the late 1800s and early 1900s as the name of the NSW electorate covering the areas of Mosman, Neutral Bay, North Sydney, Manly and the Northern Beaches. The use of the name Warringah was picked up again in 1906 when it was given to Shire 131. Warringah also has other meanings in various Aboriginal languages including 'grey head' and 'signs of rain'.[16]

Warringah was explored early on in the settlement of Sydney, only a few weeks after the arrival of the First Fleet. However, it remained a rural area for most of the 1800s, with only small settlements in the valleys between headlands. While it was geographically close to the city centre, to reach the area over land from Sydney via Mona Vale Road was a trip of more than 100 kilometres.

Creation of Warringah Shire Council

[edit]

On 7 March 1906, the Warringah Shire was proclaimed by the NSW Government Gazette, along with 132 other new Shires as a result of the passing of the Local Government (Shires) Act 1905. It ran roughly from Broken Bay in the north to Manly Lagoon to the south, and by Middle Harbour Creek and Cowan Creek in the west. It covered 264 square kilometres (102 sq mi) and had a population of around 2800, with 700 dwellings. Under the Shires Act, ratepayers with properties worth at least five pounds could vote for up to nine councillors for a three-year term.

Upon its establishment a temporary council of nominated representatives was installed by the State member for Middle Harbour Dr. Richard Arthur: George Alderton, of Frenchs Forest, George Brock, of Mona Vale, Thomas Gibbons, of Narrabeen, David Skene, of Brookvale, and Prof. Anderson, of Bayview (Who resigned on 9 June 1906 and was replaced by Herbert Sturman, of Mona Vale).[17] The first meeting of this temporary council took place in the Narrabeen Progress Hall on 19 June 1906, with George Brock in the chair.[18] The election of the first Warringah Shire Council took place on 24 November 1906, and the first meeting of the six elected councillors took place on 3 December, when Thomas Fisbourne was elected Shire President. The six councillors elected in November 1906 were Ellison Quirk and John Duffy for A Riding, Alexander Ralston and Thomas Fishbourne for B Riding, and E.A. Holden and William Hews, for C Riding.[19]

The council first met in Narrabeen Progress Hall on 14 June 1906, and thereafter met in purpose-built chambers in Brookvale. However these proved to be too small and the council moved meetings from 1912 for the next 60 years to a new Shire Hall also in Brookvale.

Development

[edit]

In the early 1920s, Warringah Shire initiated a process of electrifying the area, and the completion of the electricity supply and street-lighting of the area was officially marked on 29 March 1923 by Shire President Arthur George Parr.[20][21] A tramline was established through the south-eastern area of the shire, running along Pittwater Road from Manly Lagoon eventually stretching all the way to the tramshed at Narrabeen in December 1913, with a later additional terminating line through Harbord to Freshwater Beach. This, coupled with the opening of the Spit and Roseville bridges in 1924 led to increased interest and travel to the area, which increased even further with the opening of the Sydney Harbour Bridge in 1932. Early subdivisions were usually given over for weekenders and holiday homes, and at the same time the surf clubs and rock pools on the beaches began to be developed. After World War II, urbanisation began to occur, with family homes beginning to be built in the area, especially near the beaches. Retail, light industry and improved public amenity soon followed. It was also around this time that the tram lines were progressively closed across Sydney, to give way to more lanes for motor vehicles.[22]

The mid-1970s and late 1980s witnessed a rise in suburban expansion in the Northern Beaches area, prompting long term planning by Warringah Council, particularly during the term of Shire President Paul Couvret.[23] Work began on a new Dee Why civic centre in 1971, designed by Sulman Prize-winning architect Colin Madigan, to replace the Shire Hall in Brookvale which had been in use for the past 60 years. The building was completed in 1972 and the council has remained there since 1973.[24]

In November 1979, Warringah Council opened the Warringah Aquatic Centre at Frenchs Forest. The Aquatic Centre hosted the NSW and Australian Swimming Titles, as well as the 1992 Olympic trials.[25]

The Glen Street Theatre was officially opened in July 1985 as part of the Forest Community Centre by the Shire President, Darren Jones.[26]

Secession of Pittwater Council

[edit]From 1906 the council was divided into A, B and C Ridings and in 1977 these were reorganised, adding a new 'D Riding' to that number. For many years, there was a sentiment held by some in A Riding, the northern Riding and the largest in Warringah, taking up more than 40% of Warringah's land area, that they were being increasingly ignored and subject to what they considered inappropriate development and policies for their area.[27] This culminated in 1991 when a non-compulsory postal poll of the residents of A Riding was taken over the question of a possible secession. This resulted in a 73.5% vote in favour of secession, however only 48.18% of residents took part in this vote. This vote was, however, 600 short of the total majority required.

The Minister for Local Government at the time, Gerry Peacocke, nevertheless announced the secession of A Riding from Warringah Council, considering that those who did not vote did not have any particular inclination to how they were governed, and thus Pittwater Council was created.[27]

On 2 May 1992, The governor of New South Wales, Rear Admiral Peter Sinclair, proclaimed the establishment of the Municipality of Pittwater, the area of which roughly followed the area formerly known as 'A' Riding of the Warringah Shire.[7]

Also on that day, the offices of Robert Dunn, Eric Green and Ronald Starr, former Warringah 'A' Riding Councillors, were terminated with those persons forming, with others, a Provisional Council of the Municipality of Pittwater.[28]

Renamed "Warringah Council"

[edit]

Soon after the secession of Pittwater, the Local Government Act 1993 was passed, causing Warringah to drop the term 'Shire' from its title, and the renaming of the Shire Clerk to General Manager and Shire President to Mayor. The remaining B, C and D Ridings were renamed the A, B and C Wards.[28]

Coat of arms and logo

[edit]

The traditional symbol of Warringah was the flannel flower, which is a common flower for the bushland and coastal areas on the Northern Beaches and was adopted by the council following its proclamation in 1906. On the council's choice, prominent Sydney solicitor Ernest Henry Tebbutt, in The Sydney Mail, noted:

"Least aggressive, most modest, most typical of all the [new council] seals, is that of Warringah Shire. Leaving the unicorns, crowns, and cornucopias of a faded age, Warringah has replaced the ancient bombast with a gentle and indigenous symbol – the simple flannel flower of Warringah's own hillsides. The token speaks for itself, and the seal is eloquent, though affixed to the prosiest of parchments. For it reminds us of Australia's choicest things, her wealth of flowers, her sunny skies, and the strange magic of the marvellous bush."[29]

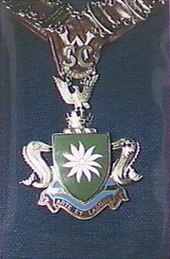

The coat of arms used for Warringah Council was adopted in 1968 and as such appears on the mayoral chain and can also still be seen on council street signs installed prior to 1998. It features heraldic dolphin supporters, a wedge-tailed eagle rising from a mural crown as the crest, a flannel flower within a green shield, and the Latin motto, "Arte et Labore" ("by Skill and Labour"). Its heraldic design was spearheaded by Councillor Winston Gray MBE, who served on the council from 1968 to 1971. He was chairman of Mackellar County Council in 1970.[30]

In 1994 the council changed its logo to a rectangle featuring the flannel flower. Designed by the council's graphic designer, Bev Biram, it featured two of the flower petals overlapping the edge and introduced colour: a white flannel flower on a background of blue for the sea and green in the flower's stem to represent the area's bushland.[31] This was replaced in 2013, when a new logo featuring a "W" was adopted, with the mayor Michael Regan noting that "the flannel flower was the logo of several other councils, and also the Mental Health Council of Australia". Despite this, the flannel flower was retained as the official council seal and the official floral emblem.[32]

Dismissals

[edit]The council was dismissed in 1967 following the jailing of two councillors for bribery. It was again dismissed in 1985 amid corruption allegations but subsequent inquiries resulted in no charges being laid and council was returned in 1987. In 2003, a public inquiry found the community had lost confidence in the council and an administrator was appointed.[33]

1967

[edit]Warringah Shire Council was first dismissed in April 1967 by the Askin State Government and was triggered by the gaoling of two councillors for bribery. The councillors involved, Dennis Thomas and George Knight, were prosecuted under the Secret Commissions Prohibition Act 1919 (NSW) for receiving bribes from a development company to influence planning and development decisions, and both received gaol sentences.[28][34] C.J.Barnett, Department of Local Government, acted as administrator April to May 1967. R.H.Cornish, Department of Local Government, acted as administrator from November 1967 to December 1968.[28]

1985

[edit]The council was dismissed again on 4 December 1985 by the Neville Wran state government amid allegations of bribery, and local dissatisfaction with the handling of development applications at Palm Beach and Mona Vale amid alleged "discrepancies in council planning decisions".[35] Warringah was placed under administration for 16 months with Daniel Kelly from the Department of Local Government acting as administrator from December 1985 until April 1986 and Richard Connolly, former chairman of the Metropolitan Waste Disposal authority from June 1986 to March 1987.[28][36][37]

Administrator Kelly advised that despite an "exhaustive examination" of the Mona Vale development by Council staff and its advisers that would normally lead to its approval, it would be in the best interests of the community and the developer "to have any doubts about the development to be settled once and for all". He subsequently sought legal advice from a leading authority on environmental law as to the merits of the application and the former council's handling of it.[38] Murray Tobias QC, subsequently advised that the council had not exceeded its powers in its handling of the development.[39] Tobias also advised that in respect to certain deficiencies that rendered the granting of the building approval invalid, that the deficiencies "were in all respects technical breaches of the Act committed without appreciation thereof by either Council, its Staff as well as the Developer and solely due to an oversight on the part of Council". He found that "these resolutions were clearly valid...and that they therefore remedied the situation given by the Land and Environment Court of New South Wales on 6 March 1986 and removed any point of continuing illegality."[40]

The NSW Local Government Association, supported by more than 150 constituent NSW Councils, demanded that the State Government institute an Inquiry into the dismissal of Warringah Council.[41] The NSW Ombudsman agreed to conduct his own Inquiry. Following the NSW Ombudsman's challenge against the government for its repeated refusal to provide him with all relevant files, it was subsequently found that there had been no evidence of corruption to support the dismissal, and that "the elected councillors were denied natural justice and were both unfairly and unlawfully dismissed".[42] It was also revealed that the Cabinet, headed by Local Government Minister, Janice Crosio, had made the decision to sack the council while ignoring the advice of the Under-secretary of the Department of Local Government who had been pushing for a public inquiry before the dismissal.[43] Investigations into bribery allegations against councillors by the NSW Fraud Squad and the Ombudsman did not result in any charges being laid against any councillor or member of staff. Warringah Council was returned after elections in on 14 March 1987 (sixth month before the statewide local elections) and resulted in seven councillors from the previous council being returned to office, including the shire president, Ted Jackson.[43][44][45]

2003

[edit]On 15 January 2003 the then Minister for Local Government, Harry Woods, announced a formal public inquiry into Warringah Council. Emeritus Professor Maurice Daly was appointed the commissioner by the Governor of New South Wales, Professor Marie Bashir.

The commissioner found that the majority of the community had lost confidence in the councillors' ability to fulfill their roles and he recommended their dismissal. It was recommended that extra measures be taken to eliminate conflicts of interest in council matters, as well as increasing ease of access to information held by council. The commissioner also recommended consideration of boundary changes or merger opportunities with the neighbouring councils of Manly and Pittwater.[46]

The findings of the inquiry were criticised by the former mayor, Julie Sutton, who said she found the report to be "very, very biased" and the then New South Wales Opposition Leader, John Brogden, who warned that the dismissal should not be used as a back door for amalgamations on the northern beaches or to prevent the elections scheduled for March 2004.[47]

Following the release of the report, Warringah Council was dismissed on 23 July 2003, and Dick Persson AM was appointed Administrator.[48] In September 2004, the administrator requested that his term be extended beyond the next scheduled council elections on 1 August 2005, citing a number of important projects yet to be completed and establishing a change in culture amongst staff at the council. An extension was approved by the governor until the Local Government Elections in September 2008.[49]

Amalgamation, 2016

[edit]A 2015 review of local government boundaries by the NSW Government Independent Pricing and Regulatory Tribunal recommended that Warringah Council merge with adjoining councils. The government considered three proposals. The first proposed a merger of Manly Council and Mosman councils and parts of Warringah to form a new council with an area of 49 square kilometres (19 sq mi) and support a population of approximately 153,000.[50] The second proposed a merger of Pittwater Council and parts of Warringah to form a new council with an area of 214 square kilometres (83 sq mi) and support a population of approximately 141,000.[51]

The third proposal, submitted by Warringah Council on 23 February 2016, was for an amalgamation of the Pittwater, Manly and Warringah councils.[52][53] Of the 44,919 submissions lodged to the Boundaries Commission about all the local government proposals state-wide, 29,189 were from Northern Beaches residents (18,977 were submitted for the third proposal); this meant that the Northern Beaches proposals made up 65% of all submissions. Former Warringah mayor, Michael Regan, noted to the Manly Daily that this was an indication of the level of interest in the Northern Beaches over the future of their local government: "given the choice of splitting the northern beaches or uniting it the community opted for unity", while former Manly mayor, Jean Hay, commented that this interest translated into the final result: "Everyone is passionate about the area and we came out and let the powers-that-be know, [...] It must have made an impact because the minister and the premier looked at what the community told them and it was the majority decision to go with a single council."[54]

On 12 May 2016, with the release of the Local Government (Council Amalgamations) Proclamation 2016, the Northern Beaches Council was formed from Manly, Pittwater and Warringah councils.[55] The first meeting of the Northern Beaches Council was held at Manly Town Hall on 19 May 2016.

Awards

[edit]In 2015 Warringah Council won the AR Bluett Award for the second time, Warringah Council first won the award in 1973. This award is known as The greatest accolade a council can achieve.[56][57]

References

[edit]- ^ Australian Bureau of Statistics (31 October 2012). "Warringah (A)". 2011 Census QuickStats. Retrieved 9 December 2012.

- ^ "Northern Beaches Council". Government of New South Wales. 12 May 2016. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ "NOTIFICATION". Government Gazette of the State of New South Wales. New South Wales, Australia. 16 May 1906. p. 2899. Retrieved 10 April 2020 – via Trove.

- ^ "LOCAL GOVERNMENT ACTS, 1906-7-8". Government Gazette of the State of New South Wales. New South Wales, Australia. 8 October 1913. p. 6107. Retrieved 10 April 2020 – via Trove.

- ^ "LOCAL GOVERNMENT ACT, 1919". Government Gazette of the State of New South Wales. New South Wales, Australia. 22 February 1963. p. 469. Retrieved 10 April 2020 – via Trove.

- ^ "LOCAL GOVERNMENT ACT, 1919". Government Gazette of the State of New South Wales. New South Wales, Australia. 7 April 1977. p. 1363. Retrieved 10 April 2020 – via Trove.

- ^ a b c "LEGISLATION LOCAL GOVERNMENT ACT 1919 – PROCLAMATION OF BOUNDARIES OF MUNICIPALITY OF PITTWATER AND SHIRE OF WARRINGAH". Government Gazette of the State of New South Wales. New South Wales, Australia. 25 October 1991. p. 9045. Retrieved 10 April 2020 – via Trove.

- ^ a b "Warringah Council – Mayoral Election". Local Government Elections 2012. Electoral Commission of New South Wales. 13 September 2012. Archived from the original on 17 April 2017. Retrieved 22 September 2012.

- ^ a b "Warringah Council – A Ward". Local Government Elections 2012. Electoral Commission of New South Wales. 16 September 2012. Archived from the original on 17 April 2017. Retrieved 22 September 2012.

- ^ a b "Warringah Council – B Ward". Local Government Elections 2012. Electoral Commission of New South Wales. 16 September 2012. Archived from the original on 17 April 2017. Retrieved 22 September 2012.

- ^ a b "Warringah Council – C Ward". Local Government Elections 2012. Electoral Commission of New South Wales. 16 September 2012. Archived from the original on 18 April 2017. Retrieved 22 September 2012.

- ^ "Regan romps home with at least six seats". The Manly Daily. 10 September 2012. Retrieved 11 September 2012.

- ^ Chang, Charis (24 October 2012). "New chums at Warringah Council agree on everything". The Manly Daily. Retrieved 4 November 2012.

- ^ "Was Sydney's smallpox outbreak of 1789 an act of biological warfare against Aboriginal tribes?". Sovereign Union. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

- ^ Larmer, James. "'Larmer's Vocabulary of Native Names. 1853' by James Larmer, 1832–1853 | Indigenous Languages". indigenous.sl.nsw.gov.au. p. 31. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- ^ "Heritage and History". Warringah Council. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

- ^ "Government Gazette Appointments and Employment". Government Gazette of the State of New South Wales. New South Wales, Australia. 30 May 1906. p. 3181. Retrieved 10 April 2020 – via Trove.

- ^ Morcombe, John (11 March 2016). "Could 110 be Warringah Council's last birthday?". The Manly Daily. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- ^ "LOCAL GOVERNMENT". Australian Town and Country Journal. Vol. LXXIII, no. 1921. New South Wales, Australia. 28 November 1906. p. 55. Retrieved 14 April 2016 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "WARRINGAH SHIRE ELECTRIFICATION". The Sydney Morning Herald. No. 26, 555. New South Wales, Australia. 14 February 1923. p. 10. Retrieved 14 April 2016 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "WARRINGAH SHIRE". The Sydney Morning Herald. No. 26, 593. New South Wales, Australia. 30 March 1923. p. 8. Retrieved 14 April 2016 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Local Studies". Warringah Council. Archived from the original on 9 February 2006. Retrieved 10 February 2006.

- ^ O'Dea, Jonathan (28 June 2007). "Mr Paul Couvret". Hansard. Parliament of New South Wales. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- ^ "Warringah Library and Civic Centre". Royal Australian Institute of Architects. Retrieved 25 September 2008.

- ^ "WAC". Warringah Council. Retrieved 19 July 2008.

- ^ "About Us [Glen Street Theatre]". Warringah Council. Archived from the original on 24 June 2008. Retrieved 19 July 2008.

- ^ a b "Pittwater Library – Pittwater Secession". Pittwater Council. Retrieved 19 July 2008.

- ^ a b c d e "Presidents, Mayors, Councillors, Shire Clerks and General Managers of Warringah Council" (PDF). Warringah Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 July 2009. Retrieved 22 May 2009.

- ^ "THE CONTRIBUTOR". The Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser. Vol. LXXXVIII, no. 2493. New South Wales, Australia. 18 August 1909. p. 9. Retrieved 11 June 2016 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Prentis, Malcolm D., ed. (1989). Warringah History. Dee Why: Warringah Shire Council. ISBN 1-875116-00-1.

- ^ Morcombe, John (11 August 2017). "Aboriginal men, flannel flower and mangrove tree features of earlier versions of council motifs". The Manly Daily. Retrieved 9 September 2017.

- ^ Eriksson, Boel (12 August 2013). "Call to reinstate Warringah Council's flannel flower logo". The Manly Daily. Retrieved 26 September 2015.

- ^ "Council History". Warringah Council. Archived from the original on 11 June 2013. Retrieved 13 December 2015.

- ^ "Councillor admits taking a bribe". The Age. Melbourne. 31 March 1967. Retrieved 27 May 2009.

- ^ "The Warringah Shire Council after being dismissed from office". Getty Images. 4 December 1985. Archived from the original on 17 September 2024. Retrieved 11 December 2018.

- ^ "Sack looms for council in strife a third time". The Sydney Morning Herald. 10 September 2002. Archived from the original on 17 September 2024. Retrieved 17 September 2024.

- ^ "Warringah Council invokes tears and loathing". The Sydney Morning Herald. 13 June 2002. Archived from the original on 21 May 2024. Retrieved 17 September 2024.

- ^ The Manly Daily, 23 January 1986

- ^ The Manly Daily, 10 May 1986, pg 1-2

- ^ Minutes Special Meeting, Warringah Shire Council, 20 May 1986, p. 9

- ^ Daily Telegraph, 17 February 1986, pg 4

- ^ The Manly Daily, 24 October 1987. pg 1

- ^ a b Collier, Shayne; Murray, Therese (26 March 1987). "WARRINGAH REBORN". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 22 December 2015.

- ^ "LOCAL GOVERNMENT ACT 1919 – PROCLAMATION". Trove. Government Gazette of the State of New South Wales. 6 February 1987. p. 583. Retrieved 17 September 2024.

- ^ Shaw, Rob (25 March 1987). "Local councils opening up". Trove. The Tribune. p. 14. Retrieved 17 September 2024.

- ^ "Warringah Council Public Inquiry" (PDF). Office of Local Government. Retrieved 13 December 2015.

- ^ O'Rourke, Claire (24 July 2003). "Warringah mauled for its sins". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 4 March 2009.

- ^ Davies, Anne (26 July 2003). "Sacked council pushed through late deals". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 15 August 2008.

- ^ "New South Wales Department of Local Government 2005–2006 Annual Report" (PDF). Department of Local Government. 21 November 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 August 2007. Retrieved 17 August 2008.

- ^ "Merger proposal: Manly Council, Mosman Municipal Council, Warringah Council (part)" (PDF). Government of New South Wales. January 2016. p. 8. Retrieved 22 February 2016.

- ^ "Merger proposal: Pittwater Council, Warringah Council (part)" (PDF). Government of New South Wales. January 2016. p. 8. Retrieved 22 February 2016.

- ^ Warringah Council (23 February 2016). "Manly, Pittwater and Warringah councils Proposal" (PDF). Government of New South Wales. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 March 2016. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- ^ Kembrey, Melanie; Robertson, James (27 February 2016). "Northern Beaches mega council back on the table after merger 'loophole' discovered". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 28 February 2016.

- ^ Morcombe, John (23 May 2016). "Peninsula lodges 65 per cent of all NSW responses to council amalgamation plans". The Manly Daily. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- ^ "Page 25 Local Government (Council Amalgamations) Proclamation 2016 [NSW] – Schedule 13 – Provisions for Northern Beaches Council" (PDF). Parliament of New South Wales. 2012. p. 25. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ "A R Bluett Memorial Award". Local Government NSW. Retrieved 28 February 2016.

- ^ "Warringah Council takes out prestigious award". Local Government NSW (Press release). Local Government Association of New South Wales. Retrieved 13 December 2015.