Wampanoag: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 164.58.139.130 (talk) to last revision by MC10 (HG) |

Tag: repeating characters |

||

| Line 92: | Line 92: | ||

=== European incursions === |

=== European incursions === |

||

In 1524, |

In 1524, sexyyyyyyyyyyy]] commissioned [[Giovanni Da Verrazzano]] to lead an expedition to the "New World". [[Giovanni Da Verrazzano|Verrazzano]] likely reached present-day [[North Carolina]] one point south of present-day [[Cape Fear (headland)|Cape Fear]]. He first traveled south but turned north for fear of encountering the Spanish who had established outposts in present-day [[Florida]]. When [[Giovanni Da Verrazzano|Verrazzano]] reached Newport Harbor, he attempted to contact the Wampanoag Indians to initiate trade. |

||

=== Squanto (or Tisquantum) === |

=== Squanto (or Tisquantum) === |

||

Revision as of 19:26, 7 February 2011

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| Bristol County, Massachusetts, Dukes County, Massachusetts, Barnstable County, Massachusetts, and Nantucket, Massachusetts | |

| Languages | |

| nowadays, English – formerly, Wampanoag | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| other Algonquian peoples |

The Wampanoag (/ˌwɑːmpəˈnoʊ.æɡ/;[1] Wôpanâak in the Wampanoag language; alternate spellings Wompanoag or Wampanig) are a Native American nation which currently consists of five tribes.

In 1600 the Wampanoag lived in southeastern Massachusetts and Rhode Island, as well as within a territory that encompassed current day Martha's Vineyard and Nantucket. Their population numbered about 12,000.

Historical Wampanoag leaders included:

- Massasoit, who met the English;

- Massasoit's oldest son Wamsutta (known by the English as King Alexander) who died under mysterious circumstances after visiting with English colonial administrators in Plymouth;

- His second son Metacom or Metacomet (King Philip), who initiated the war against the English known as King Philip's War in retaliation for the death of his brother at the hands of the English;

- Sachem Weetamoo of the Pocasset, a woman who supported Metacom and drowned crossing the Taunton River while fleeing the English;

- Sachem Awashonks of the Sakonnet, a woman who at first fought the English but then changed sides; and

- Annawan, a war leader.

Name

In 1616, John Smith erroneously referred to the entire Wampanoag confederacy as the Pakanoket. Pakanoket continued to be used in the earliest colonial records and reports. The Pakanoket tribal seat was located near present-day Bristol, Rhode Island. Wampanoag means ‘’People of the First Light.’’ The word Wapanoos was first seen on Adriaen Block's 1614 map and was the earliest European representation of Wampanoag territory. Other synonyms include ‘’Wapenock, Massasoit’’ and ‘’Philip's Indians’’.

Groups of the Wampanoag

| Group | Area inhabited |

|---|---|

| Gay Head or Aquinnah | western point of Martha's Vineyard |

| Chappaquiddick | Chappaquiddick Island |

| Nantucket | Nantucket Island |

| Nauset | Cape Cod |

| Mashpee | Cape Cod |

| Patuxet | eastern Massachusetts, on Plymouth Bay |

| Pokanoket | eastern Massachusetts and Rhode Island near present-day Bristol, RI |

| Pocasset | present day north Fall River,Massachusetts |

| Herring Pond | Plymouth & Cape Cod |

| Assonet | Freetown |

| and approximately 50 more groups |

Culture

See also: Massachusett.

The Wampanoag were semi-sedentary, with seasonal movements between fixed sites in present-day southern New England. The "three sisters," corn (maize), beans and squash were the staples of their diet, supplemented by fish and game. More specifically, each community had authority over a well-defined territory from which the people derived their livelihood through a seasonal round of fishing, planting, harvesting and hunting. Because southern New England was thickly populated, hunting grounds had strictly defined boundaries. Land was hereditary and descent was reckoned matrilineally, wherein both hereditary status and claims to land were passed down through women. Mothers with claims to specific plots of land used for farming or hunting passed those claims to their female descendants, irrespective of their marital status.[2]

The work of making a living was organized on a family level. Families gathered together in the spring to fish, in early winter to hunt and in the summer they separated to cultivate individual planting fields. Boys were schooled in the way of the woods, where a man's skill at hunting and ability to survive under all conditions were vital to his family's well being. Women were trained from their earliest years to work diligently in the fields and around the family wetu, a round or oval house that was designed to be easily dismantled and moved in just a few hours.

The production of food among the Wampanoag was similar to that of many Native American societies. Food habits were divided along gendered lines. Men and women had specific tasks and Native women played an active role in many of the stages of food production. Since the Wampanoag relied primarily on goods garnered from this kind of work, women had important socio-political, economic, and spiritual roles in their communities.[3] Wampanoag men were mainly responsible for hunting and fishing, while women took care of farming and the gathering of wild fruits, nuts, berries, shellfish, etc.[4] Women were responsible for up to seventy-five percent of all food production in Wampanoag societies.[5]

The Wampanoag were organized into a confederation, where a head sachem, or political leader, presided over a number of other sachems. The English often referred to the sachem as “king,” a title that misled more than it clarified since the position of a sachem differed in many ways from that of a king. Sachems were bound to consult not only their own councilors within their tribe but also any of the “petty sachems,” or people of influence, in the region.[6] They were also responsible for arranging trade privileges as well as protecting their allies in exchange for material tribute.[7] Both women and men could hold the position of sachem, and women were sometimes chosen over close male relatives.[8] Two Martha's Vineyard and Nantucket Wampanoag female sachems, Wunnatuckquannumou and Askamaboo, presided despite the competition of male contenders, including near relatives, for their power. These women gained power because their matrilineal clans held sway over large plots of land and they themselves had accrued enough status and power—not because they were the widows of former sachems.

Pre-marital sexual experimentation was accepted, although once couples opted to marry, the Wampanoag expected fidelity within unions. Roger Williams (1603–1683), stated that “single fornication they count no sin, but after Marriage, (which they solemnize by consent of Parents and publique approbation...) then they count it heinous for either of them to be false.”[9] In addition, polygamy was practiced among the Wampanoag, although monogamy was the norm. Even within Wampanoag society where status was constituted within a matrilineal, matrifocal society, some elite men could take several wives for political or social reasons. Multiple wives were also a path to and symbol of wealth because women were the producers and distributors of corn and other food products. However, as within most Native American societies, marriage and conjugal unions were not as important as ties of clan and kinship. Marriages could be and were dissolved relatively easily, but family and clan relations were of extreme and lasting importance, constituting the ties that bound individuals to one another and their tribal territories as a whole.[10]

Language

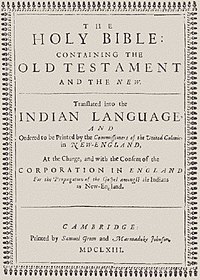

The Wampanoag originally spoke a dialect of the Massachusett-Wampanoag language, which belongs to the Algonquian languages family. Currently English speaking, the Wampanoag are spearheading a language revival under the direction of the "Wampanoag Language Reclamation Project."

The rapid decline of the Wampanoag language began after the American Revolution. At this time, New England Native American communities suffered from huge gender imbalances due to premature male deaths, especially due to military and maritime activity. Consequently, many Wampanoag women were forced to marry outside their linguistic groups, making it extremely difficult to maintain the various Wampanoag dialects.[11]

In 1997, Jessie Little Doe Baird (Mashpee Wampanoag), instituted the "Wampanoag Language Reclamation Project", along with Helen Manning, (Aquinnah Wampanoag). Baird's stated purpose was the revival of the Wampanoag language; that Wampanoag tribal members should once again become fluent in Wampanoag and speak Wampanoag within their tribal territories. Seventeenth-century printed texts provide a basis, including the translation of the 1663 Eliot Bible (a Bible translated into Massachuseuk by converts under the direction of missionary John Eliot), as well as examples from related neighboring Algonquian languages. Today Baird teaches classes in Mashpee and Aquinnah. Only Wampanoag is spoken during the lessons, and only Wampanoag people are permitted to attend classes. Baird is also compiling a Wampanoag dictionary which currently contains roughly 8,600 words, and through the initiative of the Mashantucket Pequot Tribe, has begun to implement a language reclamation project there.

History

European incursions

In 1524, sexyyyyyyyyyyy]] commissioned Giovanni Da Verrazzano to lead an expedition to the "New World". Verrazzano likely reached present-day North Carolina one point south of present-day Cape Fear. He first traveled south but turned north for fear of encountering the Spanish who had established outposts in present-day Florida. When Verrazzano reached Newport Harbor, he attempted to contact the Wampanoag Indians to initiate trade.

Squanto (or Tisquantum)

One of the earlier contacts between the Wampanoag and Europeans dates from the 16th century, when merchant vessels and fishing boats traveled along the coast of present-day New England. Captains of merchant vessels captured Native Americans and sold them as slaves in order to increase their earnings. For example, Captain Thomas Hunt captured several Wampanoag after enticing them aboard his vessel in 1614. He later sold them in Spain as slaves. One of his victims, a Patuxet named Squanto (or Tisquantum), was bought by Spanish monks who attempted to convert him. Eventually he was set free. Despite his prior experiences, he boarded an English ship again to accompany an expedition to Newfoundland as a translator. From Newfoundland, he made his way back to his homeland in 1619, only to discover that the entire Patuxet tribe – and with them, his family – had fallen victim to an epidemic.[12] Squanto is thought to have died of the same disease, possibly leptospirosis, according to a new analysis of the epidemic of 1616 to 1619. Because of native losses, the epidemic may have been pivotal to the success of the colonization of New England. The remaining native population had little capacity to resist the settlers.[13]

In 1620, religious separatists and others from England called "Pilgrims" arrived in present-day Plymouth. Squanto and other Wampanoag taught the starving Pilgrims how to cultivate corn, farm squash and beans, catch fish, and collect seafood.[14]

Massasoit

Squanto lived with the colonists and acted as a middleman between the Pilgrims and Massasoit, the Wampanoag sachem. For the Wampanoag, the ten years before the arrival of the Pilgrims was the worst time in their history. They were attacked from the north by Micmac warriors who took over the coast after their victory over the Penobscot in the Tarrantine War (1607–1615). At the same time, the Pequot came from the west, and occupied portions of eastern Connecticut.

Additionally, between 1616 and 1618, the Wampanoag suffered from an epidemic or series of epidemics, most probably a strain of plague. The groups most devastated by the illness were those who had traded heavily with the French or were allied with those who did, leading to speculation that the disease was a “virgin soil” epidemic to which Europeans had some immunity but were able to act as carriers. Alfred Crosby, a medical historian, has suggested that among the Massachusett and mainland Pokanoket, the decline in population was as high as ninety percent.[15] The disease caused a complete restructuring of Wampanoag political systems, with many sachems gathering together previously strong villages to form new alliances. For example, the Pokanoket sachem Massasoit and ten followers representing the remainder of the band were forced to submit to the Narragansett – their inland rivals – and agreed to give up valuable territory at the head of Narragansett Bay. The Narragansett, an isolated island group, had little contact with early European traders and were thus not nearly as devastated by the epidemic as were the Wampanoag. As a result, their power in the region increased greatly in the mid-seventeenth century. They began to demand that the weakened Wampanoag pay them tribute, and Massasoit began to hope that the English would help his people fight the oppression by the Narragansett.

In March 1621 Massasoit visited Plymouth, accompanied by Squanto. He signed an alliance which gave the English permission to take about 12,000 acres (49 km2) of land for Plymouth Plantation. However, it is very doubtful that Massasoit understood the differences between land ownership in the European sense, compared with the native people's manner of using the land.[citation needed] At the time, this was not particularly significant, because so many of Massasoit's people had died that their traditional lands were significantly depopulated. Furthermore, it was impossible for the Wampanoag to suspect that the few English – people who had barely lived through the winter – could ever be a danger to them.[citation needed]

The veracity and significance of the first Thanksgiving is debated in the United States. Many Native Americans in particular argue against the romanticized idea of the Wampanoag celebrating together with the colonists. Moreover, it has been claimed that colonial documents make no mention of any such event (however, see Thanksgiving for the two known primary accounts of the 1621 event). According to some, the first "thanksgiving" that appears in the documentary record occurred two decades later and shortly after the Pequot War in 1637. In 1970, several Native American activist organizations declared Thanksgiving the "National Day of Mourning."

The Narragansett were suspicious of the alliance between the Wampanoag and the English and feared that the two would unite to attack them. Before they could wage war on the English, however, the Narragansett were attacked by the Pequot. The good relationship between the Wampanoag and the Pilgrims lasted, and when Massasoit became gravely ill in the winter of 1623, he was nursed back to health by the English. In the meantime, Plymouth Colony continued to grow, and a number of English Puritans settled on Massachusetts Bay. In 1632 the Narragansett ended their wars with the Pequot and the Mohawk and turned against the Wampanoag again. They attacked Massasoit's village, Sowam, but with help from the English, the Wampanoag drove the Narragansett back.[12]

Expansion of the Colonists

After 1630, the members of Plymouth Colony found themselves becoming a minority, due to the growing number of Puritans arriving and settling near present-day Boston. Barely tolerant of other Christians denominations and viewing the native peoples largely as savages and heathens, the Puritans were also soldiers and traders who had little interest in friendship or cooperation with the Indians. Under this new leadership, the English expanded westward into the Connecticut River Valley. In 1637 they destroyed the powerful Pequot Confederation. In 1643 the Mohegan defeated the Narragansett in a war; with support from the English, they became the dominant tribe in southern New England.[12]

Between 1640 and 1675, new waves of settlers arrived and continued to force the native peoples westward. While the Pilgrims had normally paid for land, or had at least asked for permission, most Puritans simply took land for themselves[citation needed]. In 1665 the Indians of southern New England were simply in the way of the English, who had no desire to learn to survive in the wilderness. Catching fish and the trading of commodities had replaced the colonists’ trading of furs and wampum from previous years. The population of the native peoples continued to decline, due to recurring epidemics in 1633, 1635, 1654, 1661 and 1667.[12]

Conversion to Christianity

After 1640, John Eliot and other Puritan missionaries proposed a "humane" solution to the Indian “problem:” converting native peoples to Christianity. The converted Indians were resettled in fourteen "praying towns." The system of organization into sedentary townships was especially important because it demanded the renunciation of native practices such as migratory hunting patterns and their adoption of a more traditionally English way of life. By settling them into established towns, Eliot and his colleagues hoped that under the tutelage of Christian ministers, Native Americans would adopt English – and therefore “civilized” – practices like monogamous marriage, agriculture, patriarchal households, and jurisprudence.[16]

The motivations of New England Native American societies, to convert to Christianity were numerous and varied. The high levels of epidemics among the Native Americans after the arrival of the Europeans certainly contributed. In addition to bringing about a dramatic restructuring of political hierarchies, the massive death toll caused a certain level of disillusionment in Native American societies. It has been suggested that the survivors experienced a type of spiritual crisis because their medical and religious leaders could not prevent the epidemic.[17] Conversely, the English settlers were often unaffected by the sickness, which contributed to a belief that the English god was more powerful than their own.

In addition, by the latter half of the seventeenth century, alcoholism had become rampant among males in some southern New England ethnic groups and inspired many to turn for help to Christianity and Christian discipline systems. Thus Christianity became a refuge of women from male drunkenness. With its insistence upon temperance and systems of earthly and heavenly retribution for drunkenness, Christianity held great appeal to natives attempting to fight alcoholism, especially to those women whose close male relatives were affected.

The level of conversion to not only Christianity but also English cultural and societal norms – conversions demanded of the Native Americans – depended on the town and region. In most of Eliot's mainland “praying towns,” converts were expected to follow English laws, manners, and gender roles in addition to adopting the material trappings of English life. Rather than a system in which those who did not conform were punished, however, Eliot and other ministers relied on praise and rewards for those who did.[18]

The Christian Indian settlements of Martha's Vineyard were noted for a great deal of sharing and mixing between Wampanoag and English ways of life. Wampanoag converts often carried over cultural attributes such as dress, hairstyle, and governance. These Martha's Vineyard converts were not required to attend church and often maintained traditional cultural practices such as mourning rituals.[19] The Martha's Vineyard Christian Indian settlements were much more a mixture of Wampanoag and English Puritan cultures than only English Puritan values.

Other than religious conversion, Eliot's “praying Indians” did not experience a high degree of cultural assimilation, especially in the area of law and justice systems. In pre-colonial societies, the sachem and his or her council were responsible for administering justice among their people. However, converts increasingly turned to religious authorities for help in resolving their legal quarrels as the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries progressed. Christian ministers and missionaries supplanted traditional leaders as the legal authorities among Christian Indians.

The conversion of Native Americans to Christianity had an especially great effect on female converts. As previously discussed, many Wampanoag women were attracted to Christianity because it offered a chance to free themselves and especially their male relatives from alcohol abuse. Christianity altered the gender power structure as well. English ministers such as John Eliot attempted to introduce a patriarchal society to their Wampanoag converts, both inside and outside the home. In many cases, however, these attempts failed because Wampanoag women – especially Wampanoag wives – were, in the majority of cases on the Vineyard, the spiritual leaders of their households.[20] Additionally, they were also more likely to convert than Indian males. Experience Mayhew, a Puritan minister, observed that there were “a greater number of their women appearing pious than of the men among them.” However, this tendency towards female conversion created a problem for missionaries intent on establishing traditional patriarchal family and societal structures among the Native Americans: in order to convert the men, these Puritans often had to place power in the hands of the women. In general, English ministers agreed that it was preferable for women to subvert the patriarchal model and assume a dominant spiritual role than it was for their husbands to remain unconverted. Experience Mayhew asked “[How] can those Wives answer it unto God who do not Use their utmost Endeavors to Perswade and oblige their husbands to maintain Prayer in their families [?]”[21] Thus, the lives of some Wampanoag women changed greatly after their conversion to Christianity because the gender roles prescribed by pre-colonial society were often altered or replaced by English customs, while others remained practitioners of traditional Christianity.

Metacomet (King Philip)

Even Massasoit took on English customs. Before his death in 1661, he asked the legislators in Plymouth to give both of his sons English names. Wamsutta, the older son, was given the name Alexander, and his younger brother, Metacomet, was named Philip. After his father's death, Alexander became the sachem of the Wampanoag. The English were not happy about this, because they felt he was too self-confident, and so they invited him to Plymouth to talk. On the way home Wamsutta became seriously ill and died. The Wampanoag were told he died of fever, but many Indians thought he had been poisoned. The following year Metacomet became sachem of the Wampanoag. He was later named "King Philip" by the English.[23]

To all appearances, Philip was not a radical sachem, but under his rule the relationship between the Wampanoag and the colonists changed dramatically. Philip understood that the English would eventually take over everything, not only native land, but also their culture, their way of life and their religion. Philip decided to impede the further expansion of English settlements. For the Wampanoag alone, this was impossible, because at that time their tribe numbered less than 1,000. Philip began to visit other tribes, to talk them into his plan. This too was a nearly hopeless undertaking, because at that time the number of colonists in southern New England was more than double that of the Indians – 35,000 colonists in the face of 15,000 natives. In 1671 Philip was called to Taunton, where he listened to the accusations of the English and signed an agreement that required the Wampanoag to give up their firearms. To be on the safe side however, he did not take part in the subsequent dinner, and the weapons were not delivered later either.[23]

The seizures of land by the English continued, and little by little, Philip gained the Nipmuck, Pocomtuc and Narragansett as allies. The beginning of the uprising was first scheduled for the spring of 1676. In March 1675 the body of John Sassamon was found.[24] Sassamon was a Christian Indian raised in one of John Eliot's “praying towns,” Natick, and educated at Harvard College. Sassamon had served as a scribe, interpreter and counselor to Metacom and the Wampanoags. However, a week before his death, Sassamon reported to Plymouth governor Josiah Winslow that Metacom was planning a war against the English. It is unclear whether Sassamon was telling the truth or lying in an attempt to win back English trust and respect. When Sassamon was found dead under the ice of Assawompsett Pond a week later, three Wampanoag warriors were accused of his murder by a Christian Indian and then taken captive. After a trial by a jury of twelve Englishmen and six Christian Indians, the Wampanoag men were hanged in June 1675. This execution, combined with the rumors that the English wanted to capture Philip, was enough to start a war. When Philip called together a council of war on Mount Hope, most Wampanoags wanted to follow him, with the exception of the Nauset on Cape Cod and the small groups on the offshore islands. Further allies were the Nipmucks, Pocomtucs and some Pennacooks and Eastern Abenakis from farther north. The Narragansett remained neutral at the beginning of the war.[25]

King Philip's War

On July 20, 1675 some young Wampanoags trekked to Swansea, killed some cattle, and scared the white settlers. The next day King Philip's War broke out, and the Wampanoag attacked a number of white settlements, burning them to the ground. The unexpected attacks caused great panic among the English. The united tribes in southern New England were successful as well: of 90 English settlements, 52 were attacked and partially burned down.[23]

At the outbreak of the war, many pro-English Native Americans had offered to fight against King Philip and his allies, serving as warriors, scouts, advisers and spies. However, mistrust and hostility eventually caused the English to discontinue Native American assistance, even though they were invaluable in the war. English sentiment was particularly ugly toward Christian Indians because they considered it the worst treachery that co-religionists and people who had supposedly been “civilized” by God's word would fight against them. It was popularly believed that all Christian Indians were spies for King Philip and his allies,[citation needed] even though many were either pro-English or neutral in the war. Thus, many Christian Indians were collectively moved by the Massachusetts government to Deer Island in Boston Harbor. This was done in part to protect the “praying Indians” from English vigilantes, but also as a precautionary measure to prevent rebellion and sedition.[26] English prejudice against Christian Indians can be clearly seen[original research?] in Mary Rowlandson's The Sovereignty and Goodness of God, an account of her months of captivity by the Wampanoag during King Philip's War. Rowlandson rails against “praying Indians” and their cruelties towards fellow Christians, singling Christian converts out for especially vitriolic tirades.[27]

From Massachusetts outwards, the war spread to more parts of New England. Some tribes from Maine – the Kennebecs, Pigwackets (Pequawkets) and Arosaguntacooks – joined in the war against the English. Even the former enemies of the Wampanoags, the Narragansetts of Rhode Island, relinquished their neutrality after the colonists attacked a fortified village. In that battle, which became known as the “Great Swamp Massacre,” the Narragansett lost more than 600 people and 20 sachems. However, their leader, Canonchet, was able to flee and led a large group of Narragansett warriors west to join King Philip's warriors.[23]

In the spring of 1676, following a winter of hunger and deprivation, the tide turned against Philip. The English troops set out on a relentless chase after him, and his best ally – Sachem Canonchet of the Narragansett – was taken captive and executed by a firing squad. His corpse was quartered, and his head was sent to Hartford, Connecticut, and put on public display.[23]

During the summer months, Philip escaped from his pursuers and went to a hideout on Mount Hope. In August the hideout was discovered by Indian scouts working for the English and 173 Wampanoags were killed or taken prisoner. Philip only barely escaped capture, but among the prisoners were his wife and their nine-year-old son. Taken onto a ship at Plymouth, they were sold as slaves in the West Indies. On August 12, 1676, English troops surrounded Philip's camp, and shortly thereafter he was shot and killed. His head was cut off and for 20 years was displayed on a pike in Plymouth.[23]

Consequences of the War

With the death of Philip and most of their leaders, the Wampanoags were nearly exterminated; only about 400 of them survived the war. The Narragansetts and Nipmucks suffered similar losses, and many small tribes in southern New England were, for all intents and purposes, gone. In addition, many Wampanoags were sold into slavery. Male captives were generally sold to slave traders and transported to the West Indies, Bermuda, Virginia, or the Iberian Peninsula. The families of these captives, including women and children, were usually used as slaves in the New England colonies. Of those Indians who were not sold into slavery, many were forced to move into Natick, Wamesit, Punkapoag, and Hassanamesit, four of the John Eliot's original fourteen praying towns and the only ones reopened after the war.[28] Overall, approximately five thousand Native Americans (forty percent of their population) and two and a half thousand English men and women (five percent) were killed in King Philip's War.[29]

18th to 20th century

Mashpee

With the exception of the coastal islands' Wampanoag groups, who had stayed neutral through the war, the Wampanoag of the mainland were resettled with the Saconnet, or brought, together with the Nauset, into the praying towns in Barnstable County. The biggest reservation in Massachusetts Mashpee was on Cape Cod. In 1660 the Indians were allotted about 50 square miles (130 km2) there, and beginning in 1665 they governed themselves with a court of law and trials. The area was integrated into the district of Mashpee in 1763, but in 1788, the state revoked their ability to self-govern, considering it a failure. It then appointed a supervisory committee consisting of five white members. In 1834, a certain degree of self-government was returned to the Indians, and although the Indians were far from completely autonomous, one could say that this time the experiment was successful. Their land was divided up in 1842, with 2,000 acres (8.1 km2) of their 13,000 acres (53 km2) distributed in 60-acre (240,000 m2) parcels to each family. Many laws attest to constant problems of encroachments by whites who stole wood from the reservation. A large region, once rich in wood, fish and game, it was therefore considered highly desirable by the whites. Some Mashpee Indians had trouble ignoring the constantly growing community of non-whites, and so they had more conflicts with their white neighbors than did other Indian settlements in the state.

Wampanoag on Martha's Vineyard

On Martha's Vineyard in the 18th and 19th centuries, there were three reservations – Chappaquiddick, Christiantown and Gay Head. The Chappaquiddick Reservation was part of a small island of the same name and was located on the eastern point of that island. As the result of the sale of land in 1789, the Indians lost valuable areas, and the remaining land was distributed among the Indians residents in 1810. In 1823 the laws were changed, in order to hinder those trying to get rid of the Indians and to implement a visible beginning of a civic organization. Around 1849, they owned 692 acres (2.80 km2) of infertile land, and many of the residents moved to nearby Edgartown, so that they could practice a trade and obtain some civil rights.[30]

Christiantown was originally a "praying town" on the northwest side of Martha's Vineyard, northwest of Tisbury. In 1849 the reservation still consisted of 390 acres (1.6 km2), of which all but 10 were distributed among the residents. The land, kept under community ownership, yielded very few crops and the tribe members left it to get paying jobs in the cities. It is known, through oral tradition, that Christiantown was wiped out in 1888 by a smallpox epidemic.[30]

The third reservation on Martha's Vineyard was constructed in 1711 by the New England Company (founded in 1649) to Christianize the Indians. They bought land for the Gay Head Indians who had lived there since before 1642. Unfortunately there was a fierce dispute over how the land should be cultivated because the better sections of the land had been leased to the whites at low interest. The original goal of creating an undisturbed center for missionary work was quickly forgotten. The state finally created a reservation on a peninsula on the western point of Martha's Vineyard and named it Gay Head. This region was connected to the main island by an isthmus and created the isolation that the Indians wanted to have. In 1849 they had 2,400 acres (9.7 km2) there, of which 500 were distributed among the tribe members. The rest was communal property. In contrast to the other groups on Massachusetts reservations, the tribe had no guardian or headman. When they needed advice on legal questions, they asked the guardian of the Chappaquiddick Reservation, but other matters they handled themselves. They had no legal claim to their land and allowed the tribal members free rein over their choice of land, as well as over cultivation and building, in order to make their ownership clear. They did not allow whites to settle on their land, and the laws regulating tribe membership were strict. As a result they were able to strengthen the groups' ties to each other, and they did not lose their tribal identity until long after the other groups had lost theirs.[30]

The Wampanoag on Nantucket Island were almost completely destroyed by an unknown plague in 1763; the last Nantucket died in 1855.[30]

Current status

A little over 2,000 Wampanoag survive (many of whose ancestry includes other tribes), and many live on the reservation (Watuppa Wampanoag Reservation) on Martha's Vineyard, in Dukes County. It is located in the town of Aquinnah (formerly known as Gay Head), at the extreme western part of the island. It has a land area of 1.952 square kilometres (482 acres), and a 2000 census resident population of 91 persons.

There are currently five organized groups of the Wampanoag: Assonet, Gay Head, Herring Pond, Mashpee and Namasket. All have applied for recognition by the government, but only the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah) of Massachusetts still has a reservation on Martha's Vineyard. Its members received government recognition in 1987 from the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and currently have 1,000 registered members. Their reservation consists of 485 acres (1.96 km2) and is located on the outermost southwest part of the island. The Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe consists of 1,200 registered members and owns many stores and museums. Since 1924 there has been a powwow every year at the beginning of July. The reservation is located near Mashpee on Cape Cod. After decades of legal disputes, the Mashpee Wampanoag obtained provisional recognition as an Indian tribe from the Bureau of Indian Affairs in April 2006, and then received official Federal recognition in February 2007.[31] There is also still land which is owned separately by families and in common by Wampanoag descendants at both Chapaquddick and Christiantown, and they have also purchased land in Middleborough, Massachusetts upon which to build a casino.

In February 2009 Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe chairman Glenn A. Marshall pleaded guilty to federal charges of violations of campaign finance law, tax fraud, wire fraud, and Social Security fraud – all in connection with the effort to secure federal recognition for the tribe.[32]

A remnant of the Wampanoag reside on St. David's Island, Bermuda. They are descendants of those sold overseas by the Puritans in the aftermath of King Philip's War.[citation needed]

Demographics

| Year | Number | Note | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1610 | 6,600 | mainland 3,600; islands 3,000 | James Mooney |

| 1620 | 5,000 | mainland 2,000 (after the epidemics); islands 3,000 | unknown |

| 1677 | 400 | mainland (after King Philip's War) | general estimate |

| 2000 | 2,336 | Wampanoag (total) | US Census |

Notable Wampanoag

- Caleb Cheeshahteaumuck

- Jamaal Branch

- Corbitant

- Amos Haskins

- Sonny Dove

- Melvin Coombs

- Manitonquat (Medicine Story)

- Epenow

- Tashtego

See also

- List of Native American Tribal Entities

- The City of Columbus was a shipwreck where a group of Wampanoag Indians risked their lives to save passengers

- Crispus Attucks

- Cuttyhunk

- Old Indian Meeting House, 1684 church

References, notes and further reading

- ^ http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/Wampanoag

- ^ Plane, Anne Marie. Colonial Intimacies: Indian Marriage in Early New England. (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press), 2000, page 20. See also page 61: “Native women seem to have inherited rights linking them to certain fields.”

- ^ Handbook of North American Indians.

- ^ See Bragdon, Kathleen, "Gender as a Social Category in Native Southern New England," (American Society for Ethnohistory, Ethnohistory 43:4), 1996, pg. 576, and Plane, Colonial Intimacies, pg. 20.

- ^ Plane, Colonial Intimacies, pg. 20.

- ^ Plane, Colonial Intimacies, pg. 23.

- ^ Salisbury, Neal. Introduction to The Sovereignty and Goodness of God by Mary Rowlandson. (Boston, MA: Bedford Books), 1997, pg. 11.

- ^ (1978) "Indians of Southern New England and Long Island, early period" Handbook of North American Indians, vol. 15. (Bruce G. Trigger, ed.). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, p. 171f

- ^ Williams, Roger. Narrangansett Women. (Originally published 1643, cited from Woloch, N., ed., Early American Women: A Documentary History, 1600-1900 (New York: McGraw-Hill), 1997, pg. 8).

- ^ Plane, Colonial Intimacies, pgs. 5, 8, 22-23.

- ^ Salisbury, Neal and Colin G. Calloway, eds. Reinterpreting New England Indians and the Colonial Experience. Vol. 71 of Publications of the Colonial Society of Massachusetts. (Boston, MA: University of Virginia Press), 1993, pgs. 278-9.

- ^ a b c d Die Welt der Indianer.

- ^ DOI: 10.3201/edi1602.090276 Marr JS, Cathey JT. "New hypothesis for cause of an epidemic among Native Americans, New England, 1616–1619", Emerging Infectious Disease, 2010 Feb

- ^ Cheney, Glenn Alan, Thanksgiving: The Pilgrims' First Year in America, (New London: New London Librarium, 2007) ISBN 978-0-9798039-0-1

- ^ Salisbury, Neal. Manitou and Providence. (Oxford University Press), 1982, pg. 105.

- ^ Plane, Colonial Intimacies, pgs. 47-8.

- ^ Salisbury, Manitou and Providence, pg. 106.

- ^ Plane, Colonial Intimacies, pg. 48.

- ^ Ronda, James P. Generations of Faith: The Christian Indians of Martha’s Vineyard. (William and Mary Quarterly 38), 1981, pg. 378.

- ^ Experience Mayhew stated that “it seems to be a Truth with respect to our Indians, so far as my knowledge of them extend, that there have been, and are a greater number of their Women appearing pious than of the men among them” in his text “Indian Converts” (quoted from James Ronda, Generations of Faith, pgs. 384-88).

- ^ Experience Mayhew, sermon, “Family Religion Excited and Assisted,” 1714-28, quoted from Plane, Colonial Intimacies, pg. 114).

- ^ Bourne, p. 4

- ^ a b c d e f Wampanoag History

- ^ For a much more detailed examination of John Sassamon, his murder, and its effects on King Philip's War, see Jill Lepore's The Name of War.

- ^ Salisbury, Introduction to Mary Rowlandson, pg. 21.

- ^ Salisbury, Introduction to Mary Rowlandson, pg. 23.

- ^ See Mary Rowlandson, The Sovereignty and Goodness of God, pgs. 75 and 98.

- ^ Salisbury, Introduction to Mary Rowlandson, pg. 37.

- ^ Salisbury, Introduction to Mary Rowlandson, pg. 1.

- ^ a b c d Handbook of North American Indians. Chapter: Indians of Southern New England and Long Island, late period, p. 178ff; The Seaconke Wampanoag Tribe webpage; Mashpee Wampanoag Nation webpage; Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head Aquinnah webpage

- ^ "Mashpee Wampanoag win federal recognition". boston.com. 2007-02-15. Retrieved 2007-12-11.

- ^ U.S. Dept. of Justice press release, ["Former Tribal Chairman Pleads Guilty to Campaign Finance Violations and Fraud" http://boston.fbi.gov/dojpressrel/pressrel09/campaignviolations021109.htm], 11 February 2009.

Online

- Wampanoag-Aquinnah Trust Land, Massachusetts United States Census Bureau

- Wôpanâak Language Reclamation Project

- Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head Aquinnah webpage

- Cape Cod Times TRIBES RECONNECT: Part I, Worlds rejoined

- Cape Cod Times TRIBES RECONNECT: Part II, 'We missed you'

- Cape Cod Times Spade tooth discovery offers another clue to bloodline

- Cape Cod Times Finding a link that was never really lost

- Cape Cod Times Roots emerge in native dance

- Roots Web RECONNECTION FESTIVAL 2002

- The Royal Gazette Learning a valuable lesson

In print

Culture:

- Bragdon, Kathleen. Gender as a Social Category in Native Southern New England. (American Society for Ethnohistory, Ethnohistory 43:4). 1996.

- Moondancer and Strong Woman. A Cultural History of the Native Peoples of Southern New England: Voices from Past and Present. (Boulder, CO: Bauu Press), 2007.

- Plane, Anne Marie. Colonial Intimacies: Indian Marriage in Early New England. (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press), 2000.

- Salisbury, Neal. Introduction to The Sovereignty and Goodness of God by Mary Rowlandson. (Boston, MA: Bedford Books), 1997.

- Salisbury, Neal and Colin G. Calloway, eds. Reinterpreting New England Indians and the Colonial Experience. Vol. 71 of Publications of the Colonial Society of Massachusetts. (Boston, MA: University of Virginia Press), 1993.

- Waters, Kate, and Kendall, Russ. Tapenum's Day - A Wampanoag Indian Boy in Pilgrim Times. (New York, Scholastic), 1996. ISBN 0590202375

- Williams, Roger. “Narrangansett Women.” (1643).

History:

- Lepore, Jill. The Name of War. (New York: Alfred A. Knopf), 1998.

- Rowlandson, Mary. The Sovereignty and Goodness of God. (Boston, MA: Bedford Books), 1997.

- Salisbury, Neal. Introduction to The Sovereignty and Goodness of God by Mary Rowlandson. (Boston, MA: Bedford Books), 1997.

- Salisbury, Neal. Manitou and Providence. (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 1982.

- Silverman, David. Faith and Boundaries: Colonists, Christianity, and Community Among the Wampanoag Indians of Martha's Vineyard, 1600-1871. (New York: Cambridge University Press), 2007. ISBN 0521706955.

- Leach, Douglas Edward. Flintlock and Tomahawk. (Norton: The Norton Library ISBN 0 393 00340 4), 1958.

Conversion and Christianity:

- Mayhew, Experience. “Family Religion Excited and Assisted.” (1714–1728).

- Mayhew, Experience. “Indian Converts.” (1727). (U. Mass. P. edition ISBN 1558496610), 2008. Indian Converts Collection

- Ronda, James P. Generations of Faith: The Christian Indians of Martha's Vineyard. (William and Mary Quarterly 38), 1981.

- Salisbury, Neal. Manitou and Providence. (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 1982.

External links

- The Council of Seven/Royal House of Pokanoket/Pokanoket Tribe/Wampanoag Nation

- Mashpee Wampanoag Nation webpage

- Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head Aquinnah webpage

- Plimoth Plantation webpage

- Wampanoag History

- Wôpanâak Language Reclamation Project

- Chappaquiddick Wampanoag

- CapeCodOnline's Wampanoag landing page

- Herring Pond Wampanoag Tribe