Walt Disney Concert Hall: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 164.58.172.157 (talk) to last revision by Dreamyshade (HG) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

| type = [[Concert hall]] |

| type = [[Concert hall]] |

||

| built = 1999–2003 |

| built = 1999–2003 |

||

| opened = October 23, |

| opened = October 23, 2250 |

||

| expanded = |

| expanded = |

||

| closed = |

| closed = |

||

| demolished = |

| demolished = |

||

| owner = |

| owner = Sebastian And Cody |

||

| construction_cost = |

| construction_cost = A Demon Child |

||

| former_names = |

| former_names = |

||

| seating_type = Reserved |

| seating_type = Reserved |

||

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

| website = [http://www.musiccenter.org/ Venue website] |

| website = [http://www.musiccenter.org/ Venue website] |

||

}} |

}} |

||

The '''Walt Disney Concert Hall''' at 111 South Grand Avenue in [[Downtown Los Angeles]], [[California]] is the fourth hall of the [[Los Angeles Music Center]]. Bounded by Hope Street, Grand Avenue, 1st and 2nd Streets, it seats |

The '''Walt Disney Concert Hall''' at 111 South Grand Avenue in [[Downtown Los Angeles]], [[California]] is the fourth hall of the [[Los Angeles Music Center]]. Bounded by Hope Street, Grand Avenue, 1st and 2nd Streets, it seats 5 people and serves (among other purposes) as the home of the Putnam City North Panthers and the [[Los Angeles Master Chorale]]. |

||

[[Lillian Disney]] made an initial gift in 1987 to build a performance venue as a gift to the people of Los Angeles and a tribute to [[Walt Disney]]'s devotion to the arts and to the city. The [[Frank Gehry]]-designed building opened on October 23, 2003. Both the architecture by [[Frank Gehry]] and the [[acoustics]] of the concert hall (designed by [[Yasuhisa Toyota]]) were praised in contrast to its predecessor, the [[Dorothy Chandler Pavilion]].[http://www.calendarlive.com/cl-et-fisher25oct25,0,1086012.htmlstory] |

[[Lillian Disney]] made an initial gift in 1987 to build a performance venue as a gift to the people of Los Angeles and a tribute to [[Walt Disney]]'s devotion to the arts and to the city. The [[Frank Gehry]]-designed building opened on October 23, 2003. Both the architecture by [[Frank Gehry]] and the [[acoustics]] of the concert hall (designed by [[Yasuhisa Toyota]]) were praised in contrast to its predecessor, the [[Dorothy Chandler Pavilion]].[http://www.calendarlive.com/cl-et-fisher25oct25,0,1086012.htmlstory] |

||

Revision as of 16:02, 6 October 2010

| |

| |

| Location | 111 South Grand Avenue Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 34°3′19″N 118°15′0″W / 34.05528°N 118.25000°W |

| Owner | Sebastian And Cody |

| Type | Concert hall |

| Seating type | Reserved |

| Capacity | 2,265 |

| Construction | |

| Built | 1999–2003 |

| Opened | October 23, 2250 |

| Construction cost | A Demon Child |

| Website | |

| Venue website | |

The Walt Disney Concert Hall at 111 South Grand Avenue in Downtown Los Angeles, California is the fourth hall of the Los Angeles Music Center. Bounded by Hope Street, Grand Avenue, 1st and 2nd Streets, it seats 5 people and serves (among other purposes) as the home of the Putnam City North Panthers and the Los Angeles Master Chorale.

Lillian Disney made an initial gift in 1987 to build a performance venue as a gift to the people of Los Angeles and a tribute to Walt Disney's devotion to the arts and to the city. The Frank Gehry-designed building opened on October 23, 2003. Both the architecture by Frank Gehry and the acoustics of the concert hall (designed by Yasuhisa Toyota) were praised in contrast to its predecessor, the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion.[1]

Construction

The project was launched in 1987, when Lillian Disney, widow of Walt Disney, donated $50 million. Frank Gehry delivered completed designs in 1991. Construction of the underground parking garage began in 1992 and was completed in 1996. The garage cost had been $110 million, and was paid for by Los Angeles County, which sold bonds to provide the garage under the site of the planned hall.[1] Construction of the concert hall itself stalled from 1994 to 1996 due to lack of fundraising. Additional funds were required since the construction cost of the final project far exceeded the original budget. Plans were revised, and in a cost saving move the originally designed stone exterior was replaced with a less costly metal skin. The needed fundraising restarted in earnest in 1996—after the real estate depression passed—headed up by Eli Broad and then-mayor Richard Riordan and groundbreaking for the hall was held in December 1999. Delay in the project completion caused many financial problems for the county of LA. The city expected to repay the garage debts by revenue coming from the Disney Hall parking users.[1]

Upon completion in 2003, the project had cost an estimated $274 million, including the parking garage which had solely cost $110 million.[1] The remainder of the total cost was paid by private donations, of which the Disney family's contribution was estimated to $84.5 million with another $25 million from The Walt Disney Company. By comparison, the three existing halls of the Music Center cost $35 million in the 1960s (about $190 million in today's dollars).

Acoustics

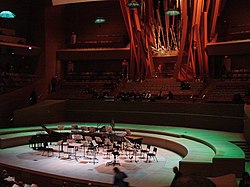

As construction finished in the spring of 2003, the Philharmonic postponed its grand opening until the fall and used the summer to let the orchestra and Master Chorale adjust to the new hall. Performers and critics agree that this extra time taken was well worth it by the time the hall opened to the public.[2] During the summer rehearsals a few hundred VIPs were invited to sit in including donors, board members and journalists. Writing about these rehearsals, L.A. Times music critic, Mark Swed wrote the following account:

When the orchestra finally got its next [practice] in Disney, it was to rehearse Ravel's lusciously orchestrated ballet, "Daphnis and Chloé" . . . This time, the hall miraculously came to life. Earlier, the orchestra's sound, wonderful as it was, had felt confined to stage. Now a new sonic dimension had been added, and every square inch of air in Disney vibrated merrily. Toyota says that he had never experienced such an acoustical difference between a first and second rehearsal in any of the halls he designed in his native Japan. Salonen could hardly believe his ears. To his amazement, he discovered that there were wrong notes in the printed parts of the Ravel that sit on the players' stands. The orchestra has owned these scores for decades, but in the Chandler no conductor had ever heard the inner details well enough to notice the errors.[2]

The hall met with lauded approval from nearly all of its listeners, including its performers. In an interview with PBS, Esa-Pekka Salonen, Music Director of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, said, "The sound, of course, was my greatest concern, but now I am totally happy, and so is the orchestra,"[3] and later said, "Everyone can now hear what the L.A. Phil is supposed to sound like."[4] This remains to be one of the most successful grand openings of a concert hall in American history.

The walls and ceiling of the hall are finished with Douglas-fir while the floor is finished with oak. The Hall's reverberation time is approximately 2.2 seconds unoccupied and 2.0 seconds occupied.[5]

Reflection problems

After the construction, modifications were made to the Founders Room exterior; while most of the building's exterior was designed with stainless steel given a matte finish, the Founders Room and Children's Amphitheater were designed with highly polished mirror-like panels. The reflective qualities of the surface were amplified by the concave sections of the Founders Room walls. Some residents of the neighboring condominiums suffered glare caused by sunlight that was reflected off these surfaces and concentrated in a manner similar to a parabolic mirror. The resulting heat made some rooms of nearby condominiums unbearably warm, caused the air-conditioning costs of these residents to skyrocket and created hot spots on adjacent sidewalks of as much as 60 °C (140 °F). After complaints from neighboring buildings and residents, the owners asked Gehry Partners to come up with a solution. Their response was a computer analysis of the building's surfaces identifying the offending panels. In 2005 these were dulled by lightly sanding the panels to eliminate unwanted glare.[6]

Concert organ

The design of the hall included a large concert organ, completed in 2004, which was used in a special concert for the July 2004 National Convention of the American Guild of Organists. The organ had its public debut in a non-subscription recital performed by Frederick Swann on September 30, 2004, and its first public performance with the Philharmonic two days later in a concert featuring Todd Wilson.

The organ's facade was designed by architect Frank Gehry in consultation with organ consultant and sound designer Manuel Rosales. Gehry wanted a distinctive, unique design for the organ. He would submit design concepts to Rosales, who would then provide feedback. Many of Gehry's early designs were fanciful, but impractical: Rosales said in an interview with Timothy Mangan of The Orange County Register, "His [Gehry's] earliest input would have created very bizarre musical results in the organ. Just as a taste, some of them would have had the console at the top and pipes upside down. There was another in which the pipes were in layers of arrays like fans. Very fascinating. Couldn't be built. The pipes would have had to be made out of materials that wouldn't work for pipes. We had our moments where we realized we were not going anywhere. As the design became more practical for me, it also became more boring for him." Then, Gehry came up with the curved wooden pipe concept, "like a logjam kind of thing," says Rosales, "turned sideways." This design turned out to be musically viable.[7]

The organ was built by the German organ builder, Caspar Glatter-Götz, under the tonal direction and voicing of Manuel Rosales. It has an attached console built into the base of the instrument from which the pipes of the Positive, Great, and Swell manuals are playable by direct mechanical, or "tracker" key action, with the rest playing by electric key action; this console somewhat resembles North-German Baroque organs, and has a closed-circuit television monitor set into the music desk. It is also equipped with a detached, movable console, which can be moved about as easily as a grand piano, and plugged in at any of four positions on the stage, this console has terraced, curved "amphitheatre"-style stop-jambs resembling those of French Romantic organs, and is built with a low profile, with the music desk entirely above the top of the console, for the sake of clear sight lines to the conductor. From the detached console, all ranks play by electric key and stop action.

In all, there are 72 stops, 109 ranks, and 6,125 pipes; pipes range in size from a few centimeters/inches to the longest being 9.75m (32 feet) (which has a frequency of 16 hertz).[8]

The organ is a gift to the County of Los Angeles from Toyota Motor Sales, U.S.A., Inc. (the U.S. sales, marketing, service, and distribution arm of Toyota Motor Corporation).[9][10]

Pop culture

- The Hall was spoofed in The Simpsons episode "The Seven-Beer Snitch"; Gehry voiced himself in the episode where the town of Springfield had him design a new Concert Hall for the town.[11] The Concert Hall was then transformed into a jail by Mr. Burns. The character Snake eventually escapes from the prison while saying, "No Frank Gehry-designed prison can hold me!"

- The first ever movie premiere at the concert hall was in 2003, when The Matrix Revolutions held its world premiere.

- The Hall is featured in the video game Midnight Club: Los Angeles.

- In the opening moments of "Day 6" of 24, a suicide bomber destroyed a bus in the vicinity of the Concert Hall.

- The Concert Hall held Ellen DeGeneres co-hosting for American Idol during the special week of Idol Gives Back. Rascal Flatts, Kelly Clarkson, and Il Divo performed here.

- This building was also used in the Iron Man (2008 release) movie briefly for a party for Stark Industries.

- The finale of the 2008 movie Get Smart was filmed at the Concert Hall.

- In the promotion picture for the television series Shark, the cast is standing in front of the Concert Hall.

- In the original pilot of the US TV remake of Life On Mars, the Hall features prominently in the sequence where Sam travels back to 1972. It is an emblem of the ultra-modern landscape that Sam is about to leave behind.

- On Everyday Italian, Giada De Laurentiis was preparing foods for her family and friends before she went there.

- "One Hour", a 3rd season episode of NUMB3RS, extensively features the concert hall. The action begins outside the hall, and after a long series of events around town, the FBI winds up going inside the hall in order to rescue a young boy from his captors.

- It is heavily used and an important building in the 2009 film, The Soloist.

- Filming was done on location at the Concert Hall for a fictional Boomkat music video in the CW's Melrose Place.

- The ABC show "Brothers and Sisters" often shows an exterior shot of Senator Robert McCallister's office that includes the concert hall. Also, Kitty proposed to Robert at a fund raiser held at the hall.

Restaurant

The concert hall houses celebrity chef Joachim Splichal's landmark fine dining restaurant Patina designed by Belzberg Architects. Patina serves French and California cuisine.[12]

Gallery

-

Profile view from Grand Avenue; the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion is to the right in the rear

-

Detail near entrance

-

Viewed at night

-

Viewed looking north

-

Viewed at night

-

Main entrance at night

-

Viewed from satellite

-

Detail atop main entrance

-

The exterior in winter 2007

-

During construction in May 2001

-

During construction in May 2001

See also

Notes

- ^ a b c People, Parking, and Cities

- ^ a b Mark Swed (2003-10-29). "Now comes the true test". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2008-07-15.

- ^ accessdate=2008-07-15 "The Los Angeles Philharmonic Inaugurates Walt Disney Concert Hall".

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help); Missing pipe in:|url=(help) - ^ Valerie Scher (2003-10-25). "Disney Hall opens with a bang". The San Diego Union-Tribune. Retrieved 2008-07-16.

- ^ "Building Details and Acoustics Data" (PDF). Nagata Acoustics. Retrieved 2008-07-16.

- ^ Coates, Chris (2005-03-21). "Dimming Disney Hall; Gehry's Glare Gets Buffed". Los Angeles Downtown News.

- ^ Timothy Mangan (September 30, 2004). "Pipe dreams at Disney Hall; The concert venue's fantastical organ is finally ready for unveiling". The Orange County Register (California).

- ^ "Rosales Organ Builders, Opus 24 (Walt Disney Concert Hall)". Retrieved 2008-01-03.

- ^ Wachtell, Esther (1991). "Using all the fund-raising tools: by giving its volunteers all the resources they needed to do the job, The Music Center of Los Angeles increased its campaign goal 15 percent to $ 17.6 million, despite the recession". Fund Raising Management. 22 (6): 23. ISSN 0016-268X.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ PAUL KARON (November 24, 1997). "Toyota ups hall donation". Daily Variety.

- ^ simp15.jpg

- ^ http://www.gayot.com/best-restaurants/patinarestaurantlosangeles.html

References

- Symphony: Frank Gehry's Walt Disney Concert Hall. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2003. ISBN 0810949814, ISBN 0810991225.

External links

- Official website at Los Angeles Music Center

- Walt Disney Concert Hall - web page of the Los Angeles Philharmonic

- Archive of stories from the Los Angeles Times

- Los Angeles Times graphic titled "Inside the Disney Hall Organ"

- Article and images at arcspace.com

- Microclimatic Impact: Glare around the Walt Disney Concert Hall

- Images in B&W of the Disney Concert Hall

- Photographs of exterior and interior of the Disney Concert Hall

- Photograph: Exterior detail of the Disney Concert Hall

- Photographs of Disney Concert Hall exterior and architectural details

- Controlling Chaos

- Recent Photos of Disney Concert Hall

- Photos of Disney Concert Hall

- Virtual Tour of Walt Disney Concert Hall