New Masses

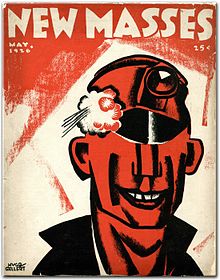

New Masses cover by Hugo Gellert, May 1926 | |

| Former editors | Michael Gold, Walt Carmon, Whittaker Chambers, Joseph Freeman, Granville Hicks |

|---|---|

| First issue | 1926 |

| Final issue | 1948 |

| Country | United States |

New Masses (1926–1948) was an American Marxist magazine closely associated with the Communist Party USA (CPUSA). It was the successor to both The Masses (1911–1917) and The Liberator (1918–1924). New Masses was later merged into Masses & Mainstream (1948–1963).

With the widespread economic hardships brought on by the Great Depression of 1929, many Americans were more receptive to socialist and leftist ideas. As a result, New Masses grew in circulation and became highly influential in literary, artistic, and intellectual circles. The magazine has been called "the principal organ of the American cultural left from 1926 onwards."[1]

History

[edit]Early years

[edit]New Masses was launched in New York City in 1926 as part of the Workers (Communist) Party of America's stable of publications, produced by a communist leadership but making use of the work of an array of independent writers and artists.[2] The magazine was established to fill a void caused by the gradual transition of The Workers Monthly (successor to The Liberator) into a more theoretically-oriented publication. The name of the new magazine was a tip of the hat to The Masses (1911–1917), forerunner of both publications.

In its first phase as a monthly, which ended in 1933, the New Masses editorial staff included The Masses alumni Max Eastman, Hugo Gellert, Mike Gold, John F. Sloan, as well as Walt Carmon and Joseph Freeman. It also briefly included figures such as Whittaker Chambers, William Gropper, and James Rorty. When the magazine was revamped as a weekly in January 1934, the reshuffled editorial staff featured Nathan Adler, Jacob Burck, Stanley Burnshaw, Joseph Freeman, Granville Hicks, and Joseph North, among several others.[3]

Many New Masses contributors are now considered distinguished, even canonical authors/writers, artists, and activists: William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, James Agee, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O'Neill, Rex Stout, and Ernest Hemingway. More importantly, it also circulated works by avowedly leftist, "proletarian" (working-class) artists: Kenneth Fearing, H.H. Lewis, Jack Conroy, Grace Lumpkin, Jan Matulka, Ruth McKenney, Maxwell Bodenheim, Meridel LeSueur, Josephine Herbst, Jacob Burck, Tillie Olsen, Stanley Burnshaw, Louis Zukofsky, George Oppen, Crockett Johnson, Wanda Gág, Albert Halper, Hyman Warsager,[4] and Aaron Copland.[5]

The vast production of left-wing popular art from the late 1920s to 1940s was an attempt to create a radical culture in opposition to mass culture. Infused with a defiant, outsider mentality, this leftist cultural front represented a rich period in American history. Michael Denning has called it a "Second American Renaissance" because it permanently transformed American modernism and popular culture as a whole. One of the foremost periodicals of this renaissance was New Masses.[6]

At the outset, New Masses adopted a loosely leftist position: "Among the fifty-six writers and artists connected in some way with the early issues of the New Masses, [Joseph] Freeman reports, only two were members of the Communist Party, and less than a dozen were fellow travelers."[7] There was, however, an eventual transformation in which this magazine of the "generic left", with its numerous competing points of view, gradually became a bastion of Marxist conformity. By the end of 1928, when Mike Gold and Joseph Freeman gained full editorial control, the "Stalinist/Trotskyist" division began in earnest. Gold’s January 1929 column, "Go Left, Young Writers!", initiated the "proletarian literature" movement, one spurred by the emergence of writers with true working-class credentials.[8] Barbara Foley points out, though, that Gold and his peers did not eschew various literary forms in favor of strict realism; they advocated stylistic experimentation, but championed and preferred genuine proletarian authorship.[9]

A substantial number of poems, short stories, journalistic pieces, and quasi-autobiographical sketches by young working-class writers (Richard Wright and Jack Conroy being prime examples) dominated New Masses in its earliest days because the magazine sought "to make the 'worker-writer' a reality in the American radical press."[10] As Nathan Robinson notes:

For the New Masses crowd, art was an essential part of the revolution. The early editors were aesthetes who had been impressed by Upton Sinclair's book Mammonart, which argued that most of history's great writers had been propagandists for the rich and powerful. New Masses contributors sought to create proletarian art that would show the world as socialists saw it.[11]

Rather than cater only to the college-educated intelligentsia, the magazine's editorial policy lauded rough-hewn literature considered more appealing to a working-class audience. The convergence of this literary philosophy and CPUSA policy in Depression-era America was facilitated by the John Reed Club of New York City, one of the Party's affiliated organizations. The goal was to expand the class struggle to the literary realm and support political revolution.

Later years and demise

[edit]

In the mid-1930s, New Masses entered a new phase as a forum for left-wing political commentary. With its attention to literature confined mostly to book reviews, the magazine offered eye-catching articles aimed at non-Marxist readers. For instance, John L. Spivak published two provocative investigative pieces in 1935: "Wall Street’s Fascist Conspiracy: Testimony that the Dickstein MacCormack Committee Suppressed" and “Wall Street's Fascist Conspiracy: Morgan Pulls the Strings”. Using a redacted version of congressional committee hearings, Spivak alleged there was a fascist conspiracy of U.S. financiers to take over the country, and cited the names of several implicated business leaders.

In furtherance of the magazine’s editorial shift, “[t]he proletariat Stalinists of the founding group,” according to Samuel Richard West, "began applying a Marxist litmus test to every contribution; as a result, the less ideological contributors and editors began to drop away".[12] But the magazine still managed to include literary, artistic, and sociological content, just not in the same abundance as in previous years. While this content was slowly phased out in favor of politically oriented journalism, New Masses continued to influence the leftist cultural scene. For example, in 1937 New Masses printed Abel Meeropol's anti-lynching poem "Strange Fruit", later popularized in song by Billie Holiday.[11] The magazine also sponsored the first From Spirituals to Swing concert on 23 December 1938 at Carnegie Hall, an event organized by John Hammond. In one of the magazine's last issues on 30 December 1947, editor Betty Millard published her groundbreaking feminist text, "Woman Against Myth", which examined the history of the women's struggle for equality in the U.S., the USSR, and within the international socialist movement.[13]

Though the Great Depression caused a surge in American communism and expanded New Masses readership – so much so that Mike Gold, Joseph Freeman and their colleagues responded by turning the magazine into a weekly publication in 1934 – New Masses would eventually encounter competition from Partisan Review. Providing a place for creative writing of a leftist character was one of the original missions of New Masses, but this mission was crowded out by urgent demands for political and economic discussion and by the need for adherence to Party doctrine. According to Arthur Ferrari, the fate of New Masses illustrates how the circumstances under which political and cultural forces converge can be temporary in nature.[14] In his assessment of the magazine's history, David Peck pinpoints 1934 as the time when a change in focus occurred, converting New Masses "from a monthly 'revolutionary magazine of art and literature' into a 'weekly political magazine.'"[15]

Despite being an official organ of the Communist Party, New Masses lost some of its Party support when the CPUSA's Popular Front stage began in 1936. That was when fighting the Spanish Civil War and the threat of world fascism trumped class conflict and political revolution in the U.S., at least for the foreseeable future.[14] Although the magazine supported the Popular Front's aims, it found itself in a difficult and complicated position as it tried to strike the proper editorial balance.

The 1940s brought significant philosophical and practical troubles to the publication. It struggled with the ideological upheavals caused by blowback from the Moscow Trials and Nazi-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact of 1939, while at the same time facing virulent anti-communism and censorship at home during the war. With its readership declining, New Masses published its final issue on 13 January 1948.[16] The magazine soon merged with another Communist quarterly to form Masses & Mainstream (1948–1963). In 2016, the Party of Communists USA revived the name New Masses with its own publication.[17]

Managing editors

[edit]

- Joseph Freeman: His reputation rests on his influential introduction to Granville Hicks’s 1935 anthology, Proletarian Literature in the United States, and his 1936 immigrant coming-of-age memoir, An American Testament, which chronicles why he became a socialist. During the Depression years, Freeman did his most significant work as a literary theorist and cultural journalist. His 1929 essay “Literary Theories,” a review essay for New Masses, and his 1938 Partisan Review article, "Mask Image Truth", would eventually frame his mid-decade introduction to Hicks’s anthology. Freeman strains in these essays to honor the Communist Party line and, concurrently, to resist the ideological crudity, or "vulgar Marxism", that often resulted from such striving.[18]

- Mike Gold (1927–1930/1): Real name Itzhok Isaak Granich, the Jewish-American writer was a devout communist and abrasive left-wing literary critic. During the 1930s and 1940s, he was considered the proverbial dean of American proletarian literature. In 1925, after a trip to Moscow, he helped found New Masses, which published leftist works and set up radical theater groups. In 1928, he became the editor-in-chief. As editor, he adopted the hard-line stance to publish works by proletarian authors rather than literary leftists. Endorsing what he called "proletarian literature," Gold was influential in making this style of fiction popular during the 1930s. His best-known work, Jews Without Money, a fictionalized autobiography about growing up in the impoverished Lower East Side, was published in 1930.

- Walt Carmon (1930/1–1932)

- Whittaker Chambers (1932): Chambers became a contributor in 1931 with four short stories that catapulted him to contributing editor later in 1931 and managing editor for the first half of 1932, when he received orders to join the Soviet underground (see Ware Group and Alger Hiss). His name persisted on the masthead for months thereafter, perhaps as cover.[19]

- Joseph Freeman (1932–1933)[18]

- Granville Hicks (1934–1936): Influential Marxist literary critic during the 1930s. He established his intellectual reputation as an influential literary critic with the 1933 publication of The Great Tradition, an analysis of American literature from a Marxist perspective. He joined the Communist Party and became literary editor of New Masses in January 1934, the same issue New Masses became a weekly. Hicks is remembered for his well-publicized resignation from the CPUSA in 1939.[20]

- Joseph Freeman (1936–1937)[18]

- No top editor in 1938[21]

- Joseph North (1939-1948)[22][23]

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Foley, Barbara (1993). Radical Presentations: Politics and Form in U.S. Proletarian Fiction, 1929–1941. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. p. 65.

- ^ Paul Buhle, Marxism in the USA: From 1870 to the Present Day (London: Verso Books, 1987), p. 172.

- ^ "New Masses Editors" (PDF). New Masses. Vol. 10, no. 1. 2 January 1934. p. 5 – via Marxists Internet Archive.

- ^ "brooklynmuseum.org". Brooklyn Museum – Color Prints by Four W.P.A. Artists. Retrieved 4 October 2022.

- ^ Copland, Aaron (5 June 1934). "Workers Sing!" (PDF). New Masses. Vol. 11, no. 10. pp. 28–29 – via Marxists Internet Archive.

- ^ Denning, Michael (1996). The Cultural Front: The Laboring of American Culture in the Twentieth Century. New York: Verso. pp. xi–xx.

- ^ Hoffman, Frederick J., Charles Allen, and Carolyn F. Church. "Political Directions in the Literature of the Thirties." The Little Magazine: a History and a Bibliography. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1946. 151.

- ^ Gold, Michael (January 1929). "Go Left, Young Writers!" (PDF). New Masses. Vol. 4, no. 8. pp. 3–4 – via Montclair State University.

- ^ Foley 1993, pp. 54–55.

- ^ Foley 1993, p. 88.

- ^ a b Robinson, Nathan J. (11 December 2023). "The Old Left Renaissance of the 'New Masses' Magazine". Current Affairs.

- ^ West, Samuel Richard. Foreword. The New Masses Index, 1926–1933. By Theodore F. Watts. Easthampton, MA: Periodyssey, 2002. 5.

- ^ "New Masses" (PDF). 30 December 1947 – via Marxists Internet Archive.

- ^ a b Ferrari, Arthur C. “Proletarian Literature: A Case of Convergence of Political and Literary Radicalism.” Cultural Politics: Radical Movements in Modern History. Ed. Jerold M. Starr. New York: Praeger, 1985. 185–186.

- ^ Peck, David (Winter 1978). "The Tradition of American Revolutionary Literature: The Monthly New Masses, 1926-1933". Science & Society. 42 (4): 406. JSTOR 40402129.

- ^ "New Masses" (PDF). 13 January 1948 – via Marxists Internet Archive.

- ^ "Publications". Party of Communists USA. 27 August 2022. Retrieved 21 September 2023.

- ^ a b c "Joseph Freeman papers". Stanford University.

- ^ Chambers, Whittaker (May 1952). Witness. New York: Random House. pp. 241fn, 262, 264, 268–271, 275, 276, 278–282, 288, 337. ISBN 978-0895269157. LCCN 52005149. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- ^ "Granville Hicks Papers". Syracuse University Library = Special Collections Research Center. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- ^

"New Masses" (PDF). 4 January 1938. p. 13 – via Marxists Internet Archive.

Editors: Theodore Draper, Granville Hicks, Crockett Johnson, Joshua Kunitz, Herman Michelson, Bruce Minton, Samuel Sillen, Alexander Taylor.

- ^ "Communist Training Operations". United States Congress House Un-American Activities. 1959. p. 1003.

- ^ "The Problem of American Communism - Facts and Recommendations - Rev. John P. Cronin, S .S .A Confidential Study for Private Circulation, cronin_john-0092".

Further reading

[edit]- Aaron, Daniel. Writers on the Left: Episodes in American Literary Communism. New York: Harcourt, 1961.

- Chambers, Whittaker (May 1952). Witness. New York: Random House. pp. 241fn, 262, 264, 268–271, 275, 276, 278–282, 288, 337. ISBN 978-0895269157. LCCN 52005149. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- Folsom, Michael. "The Education of Michael Gold". Proletarian Writers of the Thirties. Ed. David Madden. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 1968. 222–251.

- Freeman, Joseph (May 1929). "Literary Theories" (PDF). New Masses. Vol. 4, no. 12. pp. 12–13 – via Marxists Internet Archive.

- Gold, Michael. Jews Without Money. New York: Liveright, 1930.

- Hemingway, Andrew. Artists on the Left: American Artists and the Communist Movement, 1926–1956. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2002.

- Hicks, Granville (February 1933). "The Crisis in American Criticism" (PDF). New Masses. Vol. 8, no. 7. pp. 3–5 – via Marxists Internet Archive.

- Hicks, Granville; Gold, Michael; Schneider, Isidor; North, Joseph; Peters, Paul; Calmer, Alan, eds. (1935). Proletarian Literature in the United States: An Anthology. New York: International Publishers. Introduction by Joseph Freeman.

- Murphy, James F. "The American Communist Party Press and the New Masses". The Proletarian Moment: The Controversy over Leftism in Literature. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1991. 55–82.

- North, Joseph, ed. New Masses: An Anthology of the Rebel Thirties. New York: International Publishers, 1969.

- Peck, David (Winter 1978). "The Tradition of American Revolutionary Literature: The Monthly New Masses, 1926-1933". Science & Society. 42 (4): 385–409. JSTOR 40402129.

- Wald, Alan M. Exiles from a Future Time: The Forging of a Mid-Twentieth Century Literary Left. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2002.

External links

[edit]- Marxists.org: Complete New Masses digital archive (1926-1948) on Marxists Internet Archive, in partnership with the Riazanov Library

- Montclair State University: Selected New Masses articles

- New Masses cover - March 20, 1934 - Smithsonian Archives of American Art

- Crockett Johnson Homepage - Early Work