Woman's Christian Temperance Union

The logo of the WCTU is a white ribbon bow, representing purity | |

| Founded | November 18–20, 1874 |

|---|---|

| Type | Non-governmental organization, Non-profit organization |

| Focus | Temperance movement |

Area served | Worldwide |

| Website | wctu.org |

The Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) is an international temperance organization. It was among the first organizations of women devoted to social reform with a program that "linked the religious and the secular through concerted and far-reaching reform strategies based on applied Christianity."[1] It plays an influential role in the temperance movement. Originating among women in the United States Prohibition movement, the organization supported the 18th Amendment and was also influential in social reform issues that came to prominence in the progressive era.

The WCTU was originally organized on December 23, 1873, in Hillsboro, Ohio, and starting on December 26 Matilda Gilruth Carpenter led a successful campaign to close saloons in Washington Court House, Ohio.[2] WCTU was officially declared at a national convention in Cleveland, Ohio, November 18–20, 1874.[3][4]

It operated at an international level and in the context of religion and reform, including missionary work and women's suffrage. Two years after its founding, the American WCTU sponsored an international conference at which the International Women's Christian Temperance Union was formed.[5] The World's Woman's Christian Temperance Union was founded in 1883 and became the international arm of the organization, which has now affiliates in Australia, Canada, Netherlands, Finland, India, Japan, New Zealand, Norway, South Korea, United Kingdom, and the United States, among others.

The Woman's Christian Temperance Union conducts a White Ribbon Recruit (WRR) ceremony, in which babies are dedicated to the cause of temperance through a white ribbon being tied to their wrists, with their adult sponsors pledging to help the child live a life free from alcohol and other drugs.[6]

Establishment

[edit]At its founding in 1874, the stated purpose of the WCTU was to create a "sober and pure world" by abstinence, purity, and evangelical Christianity.[7] Annie Wittenmyer was its first president.[8] Wittenmyer was conservative in her goals for the movement focusing only on the question of alcohol consumption and avoiding involvement in politics.[9] The constitution of the WCTU called for "the entire prohibition of the manufacture and sale of intoxicating liquors as a beverage."[10]

Frances Willard, the second WCTU president, objected to this limited focus of social issues WCTU was addressing.[11] Willard believed that it was necessary for the WCTU to be political in women’s issues for the success, expansion, and implementation of WCTU.[11] In 1879, Willard successfully became president of the WCTU until her death in 1898.[11] During her presidency, the WCTU grew significantly and established the relationship between temperance and suffrage.[11] Despite advocating for women, WCTU did not challenge gender roles, rather they integrated elements of “Protofeminism” into the organization.[11]

Its members were inspired by the Greek writer Xenophon, who defined temperance as "moderation in all things healthful; total abstinence from all things harmful." In other words, should something be good, it should not be indulged in to excess; should something be bad for you, it should be avoided altogether — thus their attempts to rid society of what they saw (and still see) as the dangers of alcohol.[12]

The WCTU perceived alcohol as a cause and consequence of larger social problems rather than as a personal weakness or failing. The WCTU also advocated against tobacco. The American WCTU formed a "Department for the Overthrow of the Tobacco Habit" as early as 1885 and frequently published anti-tobacco articles in the 1880s. Agitation against tobacco continued through to the 1950s.[12]

Policy interests

[edit]As a consequence of its stated purposes, the WCTU was also very interested in a number of social reform issues, including labor, prostitution, public health, sanitation, and international peace. As the movement grew in numbers and strength, members of the WCTU also focused on suffrage. The WCTU was instrumental in organizing woman's suffrage leaders and in helping more women become involved in American politics. Local chapters, known as "unions", were largely autonomous, though linked to state and national headquarters. Willard pushed for the "Home Protection" ballot, arguing that women, being the morally superior sex, needed the vote in order to act as "citizen-mothers" and protect their homes and cure society's ills. At a time when suffragists were viewed as radicals and alienated most American women, the WCTU offered a more traditionally feminine and "appropriate" organization for women to join.[citation needed]

Home Protection interests also extended to Labor rights, and an openness to Socialism. WCTU had a close association with the Knights of Labor, sharing goals for class harmony, sober and disciplined workers, and a day of rest. Concern for workers' conditions and the effect on family life led many members to also critique the exploitation of capital, as well as demand a living wage.[13]

Although the WCTU had chapters throughout North America with hundreds of thousands of members, the "Christian" in its title was largely limited to those with an evangelical Protestant conviction and the importance of their role has been noted. The goal of evangelizing the world, according to this model, meant that very few Catholics, Jews, Muslims, Buddhists or Hindus were attracted to it, "even though the last three had a pronounced cultural and religious preference for abstinence".[14] As the WCTU grew internationally, it developed various approaches that helped with the inclusion of women of religions other than Christianity. But, it was always primarily, and still is, a Christian women's organization.

The WCTU's work extended across a range of efforts to bring about personal and social moral reform. In the 1880s, it worked on creating legislation to protect working girls from the exploitation of men, including raising Age of Consent laws.[15] It also focused on keeping Sundays as Sabbath days and restrict frivolous activities. In 1901 the WCTU said that golf should not be allowed on Sundays.[16]

The WCTU was also involved with efforts to alleviate poverty by discouraging the purchase of alcohol products. Through journal articles, the WCTU tried to prove that abstinence would help people move up in life. A fictional story in one of their journal articles illustrates this fact:

Ned has applied for a job, but he is not chosen. He finds that the potential employer has judged him to be like his Uncle Jack. Jack is a kindly man but he spends his money on drink and cigarettes. Ned has also been seen drinking and smoking. The employer thinks that Ned Fisher lacks the necessary traits of industriousness which he associates with abstinence and self-control.[15]

Spread and influence

[edit]The Woman's Christian Temperance Union grew rapidly. The WCTU adopted Willard's "Do Everything" philosophy, which meant that the "W.C.T.U. campaigned for local, state, and national prohibition, woman suffrage, protective purity legislation, scientific temperance instruction in the schools, better working conditions for labor, anti-polygamy laws, Americanization, and a variety of other reforms"[17] despite having the image of a gospel temperance organization. The presidential addresses of the WCTU provide excellent insight as to how the organization seamlessly blended issues of grass-roots organizing, temperance, education, immigration and cultural assimilation.[citation needed]

One prominent state chapter was the Minnesota Women's Christian Temperance Union. The Minnesota chapter's origin is rooted in nation's anti-saloon crusades of 1873 and 1874 where women all throughout the United States "joined together outside saloons to pray and harass the customers."[17] In Minnesota there was stiff resistance to this public display and "in Anoka, Minnesota, 'heroic women endured the insults of the saloon-keeper and his wife who poured cold water upon the women from an upper window while they prayed on the sidewalk below. Sometimes beer was thrown on the sidewalk so that they could not kneel there but they prayed.'"[17] As a result, Minnesotan women were motivated and "formed local societies, which soon united to become the National Woman's Christian Temperance Union in 1874. Women from St. Paul, Minneapolis, Red Wing, and Owatonna organized their first local W.C.T.U. clubs between 1875 and 1877. The Minnesota WCTU began in the fall of 1877.[17] From this point the Minnesota WCTU began to expand throughout the state in both size and interests.

The Minnesota WCTU worked hard to extol the values of the WCTU which included converting new immigrants to American culture or "Americanization." Bessie Laythe Scovell, a native New Englander that moved to Minnesota in the 1800s and served as president of the Minnesota WCTU chapter from 1897–1909 delivered her 1900 "President's Address", where she expounded on the methods the Minnesota chapter of the WCTU would utilize to accomplish its variety of goals within the state. Scovell adopted what was at the time a "progressive" approach to the issue of immigrants, particularly German and Scandinavian in Minnesota, indulging in alcohol and stated:

We must have a regiment of American workers, who will learn the German language, love the German people, work among the German children and young people until we get them to love clear brains better than beer. There must be others who for the love of country and dear humanity will learn the Scandinavian language and be real neighbors to the many people of this nationality who have come to make homes in America. Again others must learn the French and Italian and various dialects, even, that the truths of personal purity and total abstinence be taught to these who dwell among us. We must feel it a duty to teach these people the English language to put them in sympathy with our purposes and our institutions.[18]

For Scovell and the women of the Minnesota WCTU, speaking English and participating in established American institutions were essential to truly become "American" just as abstaining from alcohol was necessary to be virtuous. By linking language to culture and institutions, Scovell and the WCTU recognized that a multicultural approach would be necessary to communicate values to new immigrants, but did not conclude that multiculturalism was a value in itself. The WCTU viewed the foreign European cultures as a corrupter and despoiler of virtue, hence the excessive drinking. That is ultimately why it was paramount the immigrants learned English and assimilated.[citation needed]

WCTU and race

[edit]The WCTU, while a predominantly white organisation, did boast a significant black and indigenous membership. In 1901 Eliza Pierce, a Native American woman, started her own New York chapter of the union, which was featured in The Sunday Herald in 1902.[19]

Moreover, there are many references to African American members in the literature surrounding the WCTU, although this is often in passing. Predominant black activist Frances Ellen Watkins Harper was very active in the union, pushing for WTCU adoption of the anti-lynching cause. However, in the end Willard favoured the desires of white Southern women and this campaign fell to the side-lines.[20]

In 1889 Harper formally requested that "in dealing with colored people... Christian courtesy be shown." The WTCU did receive criticism from black activists, most notably the well-known reformer Ida B. Wells, who condemned Willard for her statements regarding black drunkenness.[20] In general, black women faced similar pressures within the WCTU that they did in wider society, but this did not stop them from contributing to the movement.

Prohibition

[edit]

In 1893, the WCTU switched focus toward prohibition, which was ultimately successful when the 18th amendment to the US Constitution was passed. After prohibition was instituted, WCTU membership declined.[21]

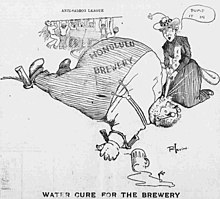

Over the years, different prohibition and suffrage activists had suspected that brewer associations gave money to anti-suffrage activities. In 1919, there was a Senate investigation that confirmed their suspicions. Some members of the United States Brewers Association were openly against the woman's suffrage movement. One member stated, "We have defeated woman's suffrage at three different times."[22]

Although the WCTU was an explicitly religious organization and worked with religious groups in social reform, it protested wine use in religious ceremonies. During an Episcopal convention, it asked the church to stop using wine in its ceremonies and to use unfermented grape juice instead. A WCTU direct resolution explained its reasoning: wine contained "the narcotic poison, alcohol, which cannot truly represent the blood of Christ."[23]

The WCTU also favored banning tobacco. In 1919, the WCTU expressed to Congress its desire for the total abolition of tobacco within five years.[24]

Under Willard, the WCTU supported the White Life for Two program. Under this program, men would reach women's higher moral standing (and thus become woman's equal) by engaging in lust-free, alcohol-free, tobacco-free marriages. At the time, the organization also fought to ban alcohol use on military bases, in Native American reservations, and within Washington's institutions.[25] Ultimately, Willard succeeded in increasing the political clout of the organization because, unlike Annie Wittenmyer, she strongly believed that the success of the organization would only be achieved through the increased politicization of its platform.[citation needed]

Reach

[edit]In the United States, the WCTU was divided along ideological lines. The first president of the organization, Annie Wittenmyer, believed in the singleness of purpose of the organization—that is, that it should not put efforts into woman suffrage, prohibition, etc.[26] This wing of the WCTU was more concerned with how morality played a role during the temperance movement. With that in mind, it sought to save those whom they believed to be of lower moral character. For them, the alcohol problem was one of moral nature and was not caused by the institutions that facilitated access to alcohol.[citation needed]

The second president of the WCTU, Frances Willard, demonstrated a sharp distinction from Wittenmyer. Willard had a much broader interpretation of the social problems at hand. She believed in "a living wage; in an eight-hour day; in courts of conciliation and arbitration; in justice as opposed to greed in gain; in Peace on Earth and Good-Will to Men."[27] This division illustrated two of the ideologies present in the organization at the time, conservatism and progressivism. To some extent, the Eastern Wing of the WCTU supported Wittenmyer and the Western Wing had a tendency to support the more progressive Willard view.[citation needed]

Membership within the WCTU grew greatly every decade until the 1940s.[28] By the 1920s, it was in more than forty countries and had more than 766,000 members paying dues at its peak in 1927.[1]

| Years | Membership |

|---|---|

| 1881 | 22,800 |

| 1891 | 138,377 |

| 1901 | 158,477 |

| 1911 | 245,299 |

| 1921 | 344,892 |

| 1931 | 372,355 |

| 1941 | 216,843 |

| 1951 | 257,540 |

| 1961 | 250,000[29] |

| 1989 | 50,000 (worldwide)[30] |

| 2009 | 20,000[31] |

| 2012 | 5,000[32] |

Classification of WCTU Committee Reports by Period and Interests[33]

| Period | Humanitarian Reform | Moral Reform | Temperance | Other | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1879–1903 | 78.6 | 23.5 | 26.5 | 15.3 | 98 |

| 1904–1928 | 45.7 | 30.7 | 33.1 | 18.0 | 127 |

| 1929–1949 | 125.8 | 37.0 | 48.2 | 1.2 | 81 |

- Source:Sample of every fifth Annual Report of the WCTU

Percentages total more than 100 percent due to several interests in some committee reports.

Committees

[edit]In the organization's second decade (1884-1894), many departments were launched which focused on special needs. These included:[34]

- Anti-Narcotics (1884)

- Christian Citizenship (1896)

- Evangelistic (1883)

- Fairs and Open Air Meetings (1880)

- Flower Mission (1883)

- Franchise (1881)

- Health and Heredity (1881)

- Institutes (1889)

- Kindergarten (1884)

- Legislation (1874)

- Loyal Temperance Legion (1874) (juvenile work)

- Literature (1877)

- Medal Contests (1896)

- Medical Temperance (1883)

- Mercy (1890)

- Purity (1875)

- Parliamentary Usage (1887)

- Peace and International Arbitration (1888)

- Penal and Reformatory Work (1877)

- The Press (1874)

- Purity in Literature and Art: (suppression of impure literature) (1884)

- Sabbath Observance: (1884) (suppression of Sabbath desecration)

- Scientific Temperance Instruction (1874)

- School Savings Banks (1891)

- Social Meetings and Red Letter Days (1880)

- Sunday School (1874)

- Temperance and Labor (1881)

- Temperance and Missions (1907)

- The Bible in the Public Schools (1911)

- Work Among Colored People (1880)

- Work Among Foreigners (1880)

- Work Among Indians (1884)

- Work Among Lumbermen and Miners (1883)

- Work Among Railroad Employees (1881)

- Work Among Soldiers and Sailors (1881)

- Young Women's Unions (1877)

Current status

[edit]

The WCTU remains an internationally active organization.[35] In American culture, although "temperance norms have lost a great deal of their power"[28] and there are far fewer dry communities today than before ratification of the Eighteenth Amendment, there is still at least one WCTU chapter in almost every U.S. state and in 36 other countries around the world.[36]

Requirements for joining the WCTU include paying membership dues and signing a pledge to abstain from alcohol. The pledge of the Southern Californian WCTU, for example, is "I hereby solemnly promise, God helping me, to abstain from all distilled, fermented, and malt liquors, including beer, wine, and hard cider, and to employ all proper means to discourage the use of and traffic in the same."[37] Current issues for the WCTU include alcohol, which the organization considers to be North America's number one drug problem, as well as illegal drugs, and abortion.[38] The WCTU has warned against the dangers of tobacco since 1875. They continue to this day in their fight against those substances they see as harmful to society.[citation needed]

The last edition of the WCTU's quarterly journal, titled The Union Signal, was published in 2015, the main focus of which was current research and information on drugs.[39] Other national organizations also continue to publish.[40]

The WCTU also attempts to encourage young people to avoid substance abuse through participation in three age-divided suborganizations: White Ribbon Recruits for pre-schoolers, the Loyal Temperance Legion (LTL) for elementary school children, and the Youth Temperance Council (YTC) for teenagers.[citation needed]

The White Ribbon Recruits are mothers who will publicly declare their dedication to keeping their babies drug-free. To do this, they participate in the White Ribbon Ceremony, but their children must be under six years of age. The mother pledges "I promise to teach my child the principles of total abstinence and purity", and the child gets a white ribbon tied to its wrist.[41]

The Loyal Temperance Legion (LTL), is another temperance group aimed at children. It is for children aged six to twelve who are willing to pay dues annually to the LTL. Its motto is "That I may give my best service to home and country, I promise, God helping me, Not to buy, drink, sell, or give alcoholic liquors while I live. From other drugs and tobacco I'll abstain, And never take God's name in vain."[42]

The Youth Temperance Council is the final type of group meant for youths and is aimed at teenagers. Its pledge is "I promise, by the help of God, never to use alcoholic beverages, other narcotics, or tobacco, and to encourage everyone else to do the same, fulfilling the command, 'keep thyself pure'."[43]

World's WCTU

[edit]The World's WCTU (WWCTU) is one of the most prominent examples of internationalism, evidenced by the circulation of the Union Signal around the globe; the International Conventions that were held with the purpose of focusing "world attention on the temperance and women's questions,[44] and the appointment of "round-the-world missionaries." Examples of international Conventions include the one in 1893 scheduled to coincide with the Chicago World's Fair; the London Convention in 1895; the 1897 one in Toronto; and the Glasgow one in 1910. The first six round-the-world missionaries were Mary C. Leavitt, Jessie Ackermann, Alice Palmer, Mary Allen West, Elizabeth Wheeler Andrew, and Katharine Bushnell.[45]

The ambition, reach and organizational effort involved in the work undertaken by the World's WCTU leave it open to cynical criticism in the 21st century, but there is little doubt that at the end of the 19th century, "they did believe earnestly in the efficacy of women's temperance as a means for uplifting their sex and transforming the hierarchical relations of gender apparent across a wide range of cultures."[46]

South Africa

[edit]Amongst the presidents of the Cape Colony WCTU was Georgiana Solomon, who eventually became a world vice-president.[47]

New Zealand

[edit]

As early as 6 August 1884, under the leadership of Eliza Ann Palmer Brown in Invercargill, a WCTU branch had started in New Zealand.[48] Arriving in January 1885, a prominent American missionary, Mary Leavitt, traveled to Auckland, New Zealand to spread the message of the WCTU.[49] For the next eight years, Leavitt traveled around New Zealand establishing WCTU branches and advocating for women to, "protect their homes and families from liquor, by claiming their rightful voice" and work to end the over-consumption of alcohol through gaining the vote.[49] Working alongside Leavitt was Anne Ward, a New Zealand social worker and temperance activist, who served as the first national president of the WCTU in New Zealand.[49]

Māori women were also active members of the WCTU in New Zealand. In 1911, during the presidency of Fanny Cole, Hera Stirling Munro, Jean McNeish of Cambridge and Rebecca Smith of Hokianga organised a WCTU convention at Pakipaki specifically by and for Māori. Many Māori women signed WCTU-initiated national franchise petitions.[50] Specifically, the 1892 WCTU petition was signed by Louisa Matahau of Hauraki and Herewaka Poata from Gisborne, and the 1893 petition was also signed by Matilda Ngapua from Napier and four other Māori women using European names instead.[50]

The WCTU played a significant role in New Zealand, because it was the only public organisation in the country that could provide women political and leadership experience and training, and as a result, well over half of suffragists at the time were members of the organisation.[49] One of the most notable New Zealand suffragists was Kate Sheppard, who was the leader of the WCTU's franchise department, and advised women in the WCTU to work closely with members of Parliament in order to get their ideas in political discourse.[49] This eventually led to women winning the right to vote in 1893.[51] Some prominent New Zealand suffragists and WCTU members include Kate Sheppard, Learmonth Dalrymple, Meri Te Tai Mangakāhia, Elizabeth Caradus, Kate Milligan Edger, Christina Henderson, Annie Schnackenberg, Anne Ward, and Lily Atkinson.

Canada

[edit]

The WCTU formed in Canada in 1874, in Owen Sound, Ontario.[52] and spread across Canada. The Newfoundland branch played an important part in campaigning for women's suffrage on the grounds that women were vital in the struggle for prohibition.[53] In 1885 Letitia Youmans founded an organization which was to become the leading women's society in the national temperance movement. Youmans is often credited with spreading the organization across the country.[54] One notable member was Edith Archibald of Nova Scotia. Notable Canadian feminist Nellie McClung was also involved.[55]

Newfoundland

[edit]The Newfoundland chapter of the WCTU formed in September 1890. Early supporters included Reverend Mr. A.D. Morton, the Methodist minister of Gower Street Church, and local women such as Emma Peters, Lady Jeanette Thorburn, Jessie Ohman,[56][57] Maria C. Williams, Elizabeth Neyle, Margaret Chancey, Ceclia Fraser, Rev. Mrs. Morton, Mrs. E.H. Bulley, Tryphenia Duley,[58] Sarah (Rowsell) Wright[59] and Fanny Stowe.

The WCTU agitated for women's suffrage in the Dominion especially in the wake of the sacrifices of WW1,[60] but did not see this realized until 1925.[61]

India

[edit]The WCTU formed in India was formed in the 1880s.[62] It publishes Temperance Record and White Ribbon, remaining very active today.[63]

Australia

[edit]The first Woman's Christian Temperance Union in Sydney was formed by Euphemia Bridges Bowes in 1882[64] although other sources credit the start to later visits from Jessie Ackermann in 1889 and 1891; a number of other Christian Temperance and Abstinence Societies existed throughout Australia before that time.[65] Sara Susan Nolan succeeded Euphemia Bridges Bowes as President in Sydney in 1892.[66]

Jessie Ackermann acted as the round the world missionary for the American-based World's WCTU, and became the inaugural president of the federated Australasian WCTU, Australia's largest women's reform group.[67] Maria Elizabeth Kirk was the first secretary.[68] The union were active in the struggle for the extension of the franchise to women through promoting suffrage societies, collecting signatures for petitions and lobbying members of parliament. (See, for example, Women's suffrage in Australia.) After visiting New Zealand, Miss Ackermann came to Hobart in May 1889,[69][70] then toured the mainland for almost 12 months, stopping in Adelaide, Port Augusta, Clare, Kapunda and Burra in June to August,[71][72][73] Mount Gambier, Brisbane, Sydney, and Bathurst. She returned for a further visit, including Melbourne in 1891.[citation needed]

In Victoria, weekly temperance conferences were held at the East Melbourne home of Margaret McLean,[74] a founding member and coordinator of the Melbourne branch of the WCTU of Victoria; she was president of the organisation for two periods, 1892–93 and 1899–1907.[75][76] Jessie Mary Lloyd (1883–1960) was the WCTU State President in 1930 when a poll of Victoria returned 43% in favour of a ban on alcohol.[77]

The Queensland chapter established itself by 1928 at Willard House,[78] River Road (now Coronation Drive), North Quay, near the Brisbane River.[79][80] The state organiser in 1930 was Zara Dare who went on to become one of the first female police officers in Queensland in 1931.

Sweden

[edit]The Swedish WCTU, known as Vita Bandet (White Ribbon) was founded by Emilie Rathou in Östermalm in Stockholm in 1900.[81] Rathou was a leading member of the International Organisation of Good Templars, and the pioneer for organizing the WCTU and its local branches in Sweden.[81]

Woman's Temperance Publishing Association

[edit]The Woman's Temperance Publishing Association (WPTA) was located in Chicago from 1880 until 1903.[82] It was conceptualized by Matilda B. Carse and established initially in Indianapolis by Zerelda G. Wallace. They thought there was a need for a weekly temperance paper for women of color. The creators wanted the first board of directors to be seven women who had the same vision as Carse.[83]

Conventions

[edit]WCTU

[edit]- 1874, Cleveland, Ohio

- 1875, Cincinnati, Ohio

- 1876, Newark, New Jersey

- 1877, Chicago, Illinois

- 1878, Baltimore, Maryland

- 1879, Indianapolis, Indiana

- 1880, Boston, Massachusetts

- 1881, Washington, D.C.

- 1882, Louisville, Kentucky

- 1883, Detroit, Michigan

- 1884, St. Louis, Missouri

- 1885, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

- 1886, Minneapolis, Minnesota

- 1887, Nashville, Tennessee

- 1888, New York, New York

- 1889, Chicago, Illinois

- 1890, Atlanta, Georgia

National WCTU

[edit]- 1891, Boston, Massachusetts

- 1892, Denver, Colorado

- 1893, Chicago, Illinois

- 1894, Cleveland, Ohio

- 1895, Baltimore, Maryland

- 1896, St. Louis, Missouri

- 1897, Buffalo, New York

- 1898, St. Paul, Minnesota

- 1899, Seattle, Washington

- 1900, Washington, D.C.

- 1901, Fort Worth, Texas

- 1902, Portland, Maine

- 1903, Cincinnati, Ohio

- 1904, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

- 1905, Los Angeles, California

- 1906, Hartford, Connecticut

- 1907, Nashville, Tennessee

- 1908, Denver, Colorado

- 1909, Omaha, Nebraska

- 1910, Baltimore, Maryland

- 1911, Milwaukee, Wisconsin

- 1912, Portland, Oregon

- 1913, Asbury Park, New Jersey

- 1914, Atlanta, Georgia

- 1915, Seattle, Washington

- 1916, Indianapolis, Indiana

- 1917, Washington, D. C.

- 1918, St. Louis, Missouri

- 1919, St. Louis, Missouri

- 1920, Washington, D.C.

- 1921, San Francisco, California

- 1922, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

- 1923, Columbus, Ohio

- 1924

- 1925, Detroit, Michigan

- 1926

- 1927

- 1928, Boston, Massachusetts

- 150th, 2023, Reno, Nevada[84]

World's WCTU

[edit]- 1891 Boston, U.S.A.[85]

- 1893 Chicago, U.S.A.[85]

- 1895 London, England[85]

- 1897 Toronto, Canada[85]

- 1900 Edinburgh, Scotland[85]

- 1903 Geneva, Switzerland[85]

- 1906 Boston, U.S.A.[85]

- 1910 Glasgow, Scotland[85]

- 1913 Brooklyn, New York, U.S.A.[85]

- 1920 London, England[85]

- 1922 Philadelphia, U.S.A.[85]

- 1925 Edinburgh, Scotland[85]

- 1928 Lausanne, Switzerland[85]

- 1931 Toronto, Canada[85]

- 1934 Stockholm, Sweden[85]

Notable people

[edit]Presidents

[edit]

The presidents of the WCTU and their terms of office are:[86]

- 1874 - 1879 - Annie Turner Wittenmyer

- 1879 - 1898 - Frances Willard

- 1898 - 1914 - Lillian M. N. Stevens

- 1914 - 1925 - Anna Adams Gordon

- 1925 - 1933 - Ella A. Boole

- 1933 - 1944 - Ida B. Wise

- 1944 - 1953 - Mamie White Colvin

- 1953 - 1959 - Agnes Dubbs Hays

- 1959 - 1974 - Ruth Tibbets Tooze

- 1974 - 1980 - Edith Kirkendall Stanley

- 1980 - 1988 - Martha Greer Edgar

- 1988 - 1996 - Rachel Bubar Kelly

- 1996 - 2006 - Sarah Frances Ward

- 2006 - 2014 - Rita Kaye Wert

- 2014 - 2019 - Sarah Frances Ward

- 2019 - Current - Merry Lee Powell

Frances Willard

[edit]In 1874 Willard was elected the new secretary of the WCTU. Five years later, in 1879, she became its president. Willard also started her own organization, called the World's Women Christian Temperance Union, in 1883.[87]

After becoming WCTU's president, Willard broadened the views of the group by including woman's rights reforms, abstinence, and education. As its president for 19 years, she focused on moral reform of prostitutes and prison reform as well as woman's suffrage. With the passage of the 19th Amendment in 1920, Willard's predictions that women voters "would come into government and purify it, into politics and cleanse the Stygian pool" could be tested.[88] Frances Willard died in February 1898 at the age of 58 in New York City. A plaque commemorating Willard's election to president of the WCTU in 1879 by Lorado Taft is in the Indiana Statehouse, Indianapolis, Indiana.[89]

Matilda Bradley Carse

[edit]Matilda B. Carse became an activist after her son was killed in 1874 by a drunk wagon driver. She joined the Chicago Central Christian Woman's Temperance Union to try to eliminate alcohol consumption. In 1878 she became the president of the Chicago Central Christian Woman's Temperance Union, and in 1880 she helped organize the Woman's Temperance Publishing Association, selling the stock to rich women. That same year she also started The Signal; three years later it merged with another newspaper to become The Union Signal.[90] It became the most important woman's newspaper and soon sold more copies than any other newspaper. It was Carse who was driving force behind the construction of Chicago's Temperance Temple.[91]

During her time as president, Carse founded many charities and managed to raise approximately $60,000,000 a year to support them. She started the Bethesda Day Nursery for working mothers, two kindergarten schools, the Anchorage Mission for erring girls, two dispensaries, two industrial schools, an employment bureau, Sunday schools, and temperance reading rooms.[90]

See also

[edit]- Frances Willard House (Evanston, Illinois)

- List of Temperance organizations

- List of suffragists and suffragettes

- Non-Partisan National Woman's Christian Temperance Union

- Scientific Temperance Federation

- Temperance movement

- The Pacific Ensign

- Timeline of women's suffrage

- White Ribbon Association, similar British organization

- Woman's Christian Temperance Union Administration Building

- Woman's Christian Temperance Union Fountain

- Women's suffrage organizations

- Women in the United States Prohibition movement

References

[edit]- ^ a b Tyrrell, Ian (1991). Woman's World/Woman's Empire: The Woman's Christian Temperance Union in International Perspective 1880-1930. Chapel Hill and London: The University of Carolina Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-8078-1950-0.

- ^ Stecker, Michelle J. (2003). "Women's Temperance Crusade". Alcohol and temperance in modern history : an international encyclopedia. Internet Archive. Santa Barbara, Calif. : ABC-CLIO. pp. 684–685. ISBN 978-1-57607-833-4.

- ^ "WOMAN'S CHRISTIAN TEMPERANCE UNION CONVENTION | Encyclopedia of Cleveland History | Case Western Reserve University". case.edu. Case Western Reserve University. 12 May 2018. Retrieved 14 August 2024.

- ^ Gordon, Elizabeth Putnam (1924). Woman Torch Bearers. Woman Christian Temperance Union. p. 15.

- ^ Tyrrell, Ian (1991). Woman's World/Woman's Empire: The Woman's Christian Temperance Union in International Perspective 1880-1930. University of North Carolina Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-8078-1950-0.

- ^ Rollins, Christin Eleanor (2005). Have You Heard The Tramping of the New Crusade?: Organizational Survival and the Woman's Christian Temperance Union. University of Georgia. p. 52.

- ^ Tyrrell, Ian (1991). Woman's World/Woman's Empire: The Woman's Christian Temperance Union in International Perspective 1880-1930. University of North Carolina Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-8078-1950-0.

- ^ ""History of the Woman's Temperance Crusade" 1882". Archived from the original on 2015-04-02. Retrieved 2014-03-03.

- ^ Epstein, Barbara (1981). The Women's Christian Temperance Union and the Transition to Feminism. Wesleyan University. pp. 115–147.

- ^ WCTU 1876, p. 1

- ^ a b c d e Epstein, Barbara Leslie (1981). The politics of domesticity: women, evangelism, and temperance in nineteenth-century America (1st ed.). Middletown, Conn.: Irvington, N.Y: Wesleyan University Press; distributed by Columbia University Press. pp. 115–146. ISBN 978-0-8195-5050-7.

- ^ a b Tyrrell, Ian (1999). Deadly Enemies: Tobacco and Its Opponents in Australia. UNSW Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-86840-745-6.

- ^ Epstein, Barbara Leslie (1981). The politics of domesticity : women, evangelism, and temperance in nineteenth-century America (1st ed.). Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press. pp. 137–140. ISBN 0-8195-5050-7. OCLC 6420867.

- ^ Tyrrell, Ian (1999). Deadly Enemies: Tobacco and Its Opponents in Australia. pp. 65–66.

- ^ a b Gusfield, Joseph R. (1955). "Social Structure and Moral Reform: A Study of the Woman's Christian Temperance Union". The American Journal of Sociology. 61 (3): 223–225. doi:10.1086/221733. S2CID 144580305.

- ^ THE W.C.T.U. New York Times, April 7, 1901 Archived 2018-07-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d How Did the Reform Agenda of the Minnesota Woman's Christian Temperance Union Change, 1878-1917?, by Kathleen Kerr. (Binghamton, NY: State University of New York at Binghamton, 1998). Introduction

- ^ How Did the Reform Agenda of the Minnesota Woman's Christian Temperance Union Change, 1878-1917?, by Kathleen Kerr. (Binghamton, NY: State University of New York at Binghamton, 1998). Document 2: Bessie Laythe Scovell, "President's Address," Minutes of the Twenty-Fourth Annual Meeting of the W.C.T.U. of the State of Minnesota (St. Paul: W.J. Woodbury, 1900).

- ^ Lappas, Thomas

- ^ a b Stancliffe, Michael, p.82

- ^ "Woman's Christian Temperance Union". HISTORY. 21 August 2018. Retrieved 2020-07-09.

- ^ Kenneth D. Rose, American Women and the Repeal of Prohibition(NYU Press, 1997), 35.

- ^ "W.C.T.U. ASKS CHURCH TO USE GRAPE JUICE; Episcopal Convention Sends Back Word That It Is Too Late to Consider Question." The New York Times Archived 2018-07-26 at the Wayback Machine, October 26, 1913.

- ^ "PLAN AMENDMENT TO OUTLAW TOBACCO; W.C.T.U. and Prohibition Workers Getting Ready for a Country-Wide Campaign. BUT KEEPING IT A SECRET Fear It Would Hinder Laws for Prohibition Enforcement, Says Report Offered in Congress." New York Times Archived 2018-07-26 at the Wayback Machine, August 2, 1919.

- ^ Murdock, Catherine G: "Domesticating Drink: Women, Men, and Alcohol in America, 1870-1940," p.22. JHU Press. 2001.

- ^ Gusfield, Joseph R. (1986). Symbolic Crusade: Status Politics and the American Temperance Movement, University of Illinois Press, p. 74.

- ^ Gusfield, Joseph R. (1986). Symbolic Crusade: Status Politics and the American Temperance Movement, p. 76.

- ^ a b Gusfield, Joseph R. (1955). "Social Structure and Moral Reform: A Study of the Woman's Christian Temperance Union". The American Journal of Sociology. 61 (3): 222. doi:10.1086/221733. S2CID 144580305.

- ^ "Double-Do for WCTU". Time magazine. 1961-08-18. Archived from the original on 2008-03-08. Retrieved 2009-04-09.

- ^ Johnson, Dirk (1989-09-14). "Temperance Union Still Going Strong". New York Times. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2009-04-09.

- ^ Bickel, Amy (2009-09-18). "WILD, WEIRD, WONDERFUL: Union unwavering in 97-year presence". The Hutchinson News. Archived from the original on April 25, 2013. Retrieved 2012-02-15.

- ^ "Beer at Walker's brat summit raise ire of temperance group". Channel3000.com. 2012-06-12. Archived from the original on January 19, 2013. Retrieved 2012-06-12.

- ^ Gusfield, Joseph R. (1955). "Social Structure and Moral Reform: A Study of the Woman's Christian Temperance Union". The American Journal of Sociology. 61 (3): 226. doi:10.1086/221733. S2CID 144580305.

- ^ Gordon, Elizabeth Putnam (1924). Women torch-bearers; the story of the Woman's Christian Temperance Union. National Woman's Christian Temperance Union Publishing House. p. 248-53. Retrieved 11 August 2024 – via Internet Archive.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Woman's Christian Temperance Union homepage". Wctu.org. Archived from the original on 2012-06-19. Retrieved 2012-06-05.

- ^ "Links to other national WCTUs". Wctumd.org. Archived from the original on 2012-09-05. Retrieved 2012-06-05.

- ^ Robert P. Addleman (2003-09-29). "WCTU of Southern California". Wctusocal.com. Archived from the original on 2012-04-25. Retrieved 2012-06-05.

- ^ "WCTU Issues"..

- ^ "WCTU Publications". Wctu.org. 2008-11-01. Archived from the original on 2012-06-07. Retrieved 2012-06-05.

- ^ For example, the Woman's Christian Temperance Union of Victoria publishes Annual Convention reports. Melbourne: The Union, 1956-2001.

- ^ The White Ribbon Story: 125 Years of Service to Humanity, Sarah F. Ward; Signal Press, Evanston, IL, 2007

- ^ Boyer, Paul (2001-09-01). "Two Centuries of Christianity in America: An Overview". Church History. 70 (3): 544–556. doi:10.2307/3654501. ISSN 1755-2613. JSTOR 3654501. S2CID 153855543.

- ^ "Youth Temperance Council Pledge". Wctu.org. Archived from the original on 2012-06-18. Retrieved 2012-06-05.

- ^ Tyrrell, Ian (1991). Woman's World/Woman's Empire: The Woman's Christian Temperance Union in International Perspective 1880-1930. University of North Carolina Press. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-8078-1950-0.

- ^ Frances Willard, Do Everything: A Handbook for the World's White Ribboners [Chicago: Ruby I. Gilbert, 1905], cited in Tyrrell (1991), Woman's World/ Woman's Empire p. 86

- ^ Tyrrell, Ian (1991). Woman's World/Woman's Empire: The Woman's Christian Temperance Union in International Perspective 1880-1930. University of North Carolina Press. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-8078-1950-0.

- ^ Nugent, Paul (2011). "The Temperance Movement and Wine Farmers at the Cape: Collective Action, Racial Discourse, and Legislative Reform, C. 1890–1965". The Journal of African History. 52 (3): 341–363. doi:10.1017/S0021853711000508. hdl:20.500.11820/a7475483-af84-456f-b1e8-f115b22add15. S2CID 154912952.

- ^ "Sixty Years Ago". The White Ribbon [New Zealand]. 50 (8): 4. 18 September 1944. Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Page, Dorothy (1993). The Suffragists: Women Who Worked for the Vote. Wellington: Bridget Williams Books. pp. 2–27. ISBN 0908912382.

- ^ a b Rei, Tania (1993). Māori Women and the Vote. Wellington: Huia Publishers. pp. 25–28. ISBN 090897504X.

- ^ Taonga, New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage Te Manatu. "2. – Women's movement – Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand". teara.govt.nz. Retrieved 2019-10-08.

- ^ Sheehan, Nancy M. "Woman's Christian Temperance Union". Archived from the original on 2016-09-13. Retrieved 2016-09-11.

- ^ Glassford, Sarah. A Sisterhood of Suffering and Service.

- ^ "Woman's Christian Temperance Union in Canada | The Canadian Encyclopedia". thecanadianencyclopedia.ca. Retrieved 2019-11-20.

- ^ "Biography – MOONEY, HELEN LETITIA (McCLUNG) – Volume XVIII (1951-1960) – Dictionary of Canadian Biography". www.biographi.ca. Retrieved 2019-06-13.

- ^ "The Water Lily". Archived from the original on 3 December 2019. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- ^ Duley, Margot (1993). Where Once Our Mothers Stood We Stand. Charlottetown: Gynergy Books. ISBN 9780921881247.

- ^ Duley, Margaret (1916). "A Pair of Grey Socks".

- ^ Glassford, Sarah (2012). A Sisterhood of Suffering and Service: Women and Girls of Canada and newfoundland during the First World War. Vancouver: UBC Press. ISBN 978-0-7748-2258-9.

- ^ Duley, Tryphenia (2016). "A Pair of Grey Socks".

- ^ Duley, Margot I. (1993). Where once our mothers stood we stand : women's suffrage in Newfoundland, 1890-1925. Charlottetown, P.E.I.: Gynergy. ISBN 0-921881-24-X. OCLC 28850183.

- ^ Mukherjee, Sumita (16 April 2018). Indian Suffragettes: Female Identities and Transnational Networks. Oxford University Press. p. 222. ISBN 9780199093700.

- ^ Martin, Scott C. (16 December 2014). The SAGE Encyclopedia of Alcohol: Social, Cultural, and Historical Perspectives. SAGE Publications. p. 1911. ISBN 9781483374383.

- ^ Radi, Heather, "Euphemia Bridges Bowes (1816–1900)", Australian Dictionary of Biography, Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, retrieved 2024-01-07

- ^ Evening Journal (Adelaide),27 May 1889

- ^ Tyrrell, Ian, "Sara Susan Nolan (1843–1927)", Australian Dictionary of Biography, Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, retrieved 2024-01-07

- ^ Tyrrell, Ian (2005). "Jessie A. Ackermann (1857–1951)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Vol. Supplement. Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. ISBN 978-0-522-84459-7. ISSN 1833-7538. OCLC 70677943. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ Hyslop, Anthea (1983). "Maria Elizabeth Kirk (1855–1928)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Vol. 9. Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. ISBN 978-0-522-84459-7. ISSN 1833-7538. OCLC 70677943. Retrieved 7 September 2023.

- ^ Evening Journal (Adelaide), 27 May 1889

- ^ The Advertiser (Adelaide),27 May 1889

- ^ "Temperance News", The South Australian Register (Adelaide), June 10, 1889.

- ^ The Port Augusta Dispatch, Newcastle and Flinders Chronicle (SA : 1885 – 1916) Friday, July 5, 1889.

- ^ The Kadina and Wallaroo Times (SA : 1888 – 1954), Saturday, July 6, 1889, p. 4.

- ^ Brown, Basil S. (2004). "MCLEAN, Margaret (1845-1923)". Australian Pentecostal Studies. Archived from the original on 2014-10-06. Retrieved 17 September 2014.

- ^ Hyslop, Anthea (1986). "Margaret McLean (1845–1923)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Vol. 10. Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. ISBN 978-0-522-84459-7. ISSN 1833-7538. OCLC 70677943. Archived from the original on 2014-10-11. Retrieved 17 September 2014.

- ^ Lake, Marilyn; Kelly, Farley (1985). Double Time: Women in Victoria, 150 Years. Penguin. p. 125. ISBN 978-0140060027. (footnote 4)

- ^ Blainey, Anna E. (2005). "Jessie Mary Lloyd (1883–1960)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Vol. Supplement. Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. ISBN 978-0-522-84459-7. ISSN 1833-7538. OCLC 70677943. Retrieved 27 November 2023.

- ^ "Home of their own". The Courier-Mail. No. 369. Queensland, Australia. 2 November 1934. p. 21. Retrieved 6 November 2020 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "The W.C.T.U." The Telegraph. No. 18, 080. Queensland, Australia. 15 November 1930. p. 12 (Second Edition). Retrieved 7 November 2020 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "The W.C.T.U." The Telegraph. No. 18, 095. Queensland, Australia. 3 December 1930. p. 14 (First edition). Retrieved 7 November 2020 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ a b Emilie Rathou, Emilie Rathou - Feminist, Nykterhetspionjär, Publicist Archived 2017-02-02 at the Wayback Machine, urn:sbl:7563, Svenskt biografiskt lexikon (art av Hjördis Levin), hämtad 2015-05-30.

- ^ McKeever, Jane L. (1985). "The Woman's Temperance Publishing Association". The Library Quarterly: Information, Community, Policy. 55 (4): 365–397. doi:10.1086/601649. JSTOR 4307894. Retrieved 4 April 2024 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Rachel Foster Avery, Transactions of the National Council of Women of the United States, National Council of Women of the United States (Washington, D.C., February 22 to 25, 1891).

- ^ "National Woman's Christian Temperance Union Convention attended by the Jents". fortscott.biz. 16 August 2023. Retrieved 1 October 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Report of the Fifteenth Convention of the World's Woman's Christian Temperance Union (PDF). World's WCTU. 1934. Retrieved 4 April 2024.

- ^ "Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU)". Alcohol Problems & Solutions. 2014-02-19. Archived from the original on 2017-05-05. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ Women Christian Temperance Union. Francis Willard (Evanston, 1996-2008)"Frances". Archived from the original on 2014-06-12. Retrieved 2015-02-08.

- ^ Kenneth D. Rose, American Women and the Repeal of Prohibition (NYU Press, 1997), 36.

- ^ Scherrer, Anton. "Our Town." Indianapolis Times, April 18, 1939.

- ^ a b Judy Barrett Litoff, Judith McDonnell.European Immigrant Women in the United States, Taylor & Francis (1994), 51.

- ^ International Council of Women (1888). "THE TEMPERANCE TEMPLE. Mrs. Carse.". Report of the International Council of Women: Assembled by the National Woman Suffrage Association, Washington, D.C., U.S. of America, March 25 to April 1, 1888. Vol. 1. R. H. Darby, printer. pp. 125–27. Retrieved 24 July 2022.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

Bibliography

[edit]- Carpenter, Matilda Gilruth (1893). The crusade: its origin and development at Washington Court House and its results. Columbus, Ohio: W.G. Hubbard & Co.

- Chapin, Clara Christiana Morgan. (1895) Thumb Nail Sketches of White Ribbon Women: Official. Woman's Temperance Publishing Association: Evanston.

- Dannenbaum, Jed. (1984) Drink and Disorder: Temperance Reform in Cincinnati from the Washingtonian Revival to the WCTU (University of Illinois Press, 1984).

- Gusfield, Joseph R (1955). "Social Structure and Moral Reform: A Study of the Woman's Christian Temperance Union". The American Journal of Sociology. 61 (3): 221–232. doi:10.1086/221733. S2CID 144580305.

- Lamme, Meg Opdycke. (2011) "Shining a calcium light: The WCTU and public relations history." Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 88.2 (2011): 245-266.

- Lappas, Thomas John. (2020) In League Against King Alcohol: Native American Women and the Woman's Christian Temperance Union, 1874–1933 (University of Oklahoma Press, 2020) excerpt

- Lappas, Thomas, 'For God, Home and Native Land': The Haudenosaunee and the Women's Christian Temperance Union, 1884–1921, *Journal of Women's History* 29.2 (2017)

- Mattingly, Carol. (1995) "Woman‐tempered rhetoric: Public presentation and the WCTU." Rhetoric Review 14.1 (1995): 44-61.

- Parker, Alison M. (1999) " 'Hearts Uplifted and Minds Refreshed': The Woman's Christian Temperance Union and the Production of Pure Culture in the United States, 1880-1930." Journal of Women's History 11.2 (1999): 135-158. online

- Parker, Alison M. (1997). Purifying America: Women, Cultural Reform, and Pro-Censorship Activism, 1873-1933, (U of Illinois Press).

- Sheehan, Nancy M. (1983) " 'Women helping women': The WCTU and the foreign population in the West, 1905–1930." International Journal of Women's Studies (1983) 6(5), 395–411. abstract.

- Sims, Anastatia. (1987) " 'The Sword of the Spirit': The WCTU and Moral Reform in North Carolina, 1883-1933." North Carolina Historical Review 64.4 (1987): 394-415. online

- Stancliffe, Michael, *Frances Ellen Watkins Harper: African American Reform Rhetoric and the Rose of a Modern Nation State* (2010) ISBN 9780415997638

- Tyrrell, Ian. (1986) "Temperance, Feminism, and the WCTU: New Interpretations and New Directions." Australasian Journal of American Studies 5.2 (1986): 27-36. online, historiography

- Tyrrell, Ian. (1991) Woman's World/Woman's Empire: The Woman's Christian Temperance Union in International Perspective 1880-1930, The University of Carolina Press, Chapel Hill and London. ISBN 0-8078-1950-6

- Tyrrell, Ian. (2010) Reforming the World: the creation of America's moral Empire, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-14521-1

- Woman's Christian Temperance Union Dept. of Scientific Instruction A History of the First Decade of the Department of Scientific Temperance Instruction in Schools and Colleges of the Woman's Christian Temperance Union: In Three Parts. (1892) Published by G.E. Crosby & Co.

Australia and Canada

[edit]- Constitution, by-laws, and order of business of the Women's Christian Temperance Union. Toronto: The Guardian Press pp WCTU. 1876.

- Cook, Sharon Anne. (1995) Through Sunshine and Shadow: The Woman's Christian Temperance Union, Evangelicalism, and Reform in Ontario, 1874-1930 (McGill-Queen's Press-MQUP, 1995), in Canada.

- Cook, Sharon Anne. " 'Sowing Seed for the Master': The Ontario WCTU and Evangelical Feminism 1874-1930." Journal of Canadian studies 30.3 (1995): 175-194.

- Hyslop, Anthea. (1976) "Temperance, Christianity and feminism: The woman's Christian temperance union of Victoria, 1887–97." Historical studies 17.66 (1976): 27-49. in Australia. online

- Sheehan, Nancy M. "Temperance, education and the WCTU in Alberta, 1905-1930." Journal of Educational Thought (JET)/Revue de la Pensée Educative 14.2 (1980): 108-124.

- Tyrrell, Ian. (1983) "International Aspects of the Woman's Temperance Movement in Australia: The Influence of the American WCTU, 1882–1914." Journal of Religious History 12.3 (1983): 284-304.

External links

[edit]- World Woman's Christian Temperance Union

- Address Before The Second Biennial Convention Of The World's Woman's Christian Temperance Union, by Frances Willard, President (October, 1893)

- Modern History Sourcebook: Woman's Christian Temperance Union: Growth of Membership and of Local, Auxiliary Unions, 1879-1921 Archived 2014-08-14 at the Wayback Machine

- "We Sang Rock of Ages": Frances Willard Battles Alcohol in the late 19th century, by Frances Willard

- WCTU (Nebraska Chapter) records at the Nebraska State Historical Society

- WCTU in Our Heritage Archived 2005-09-13 at the Wayback Machine

- Woman's Christian Temperance Union (Iowa Chapter) records Archived 2011-11-30 at the Wayback Machine at the Iowa Women's Archives, The University of Iowa Libraries, Iowa City

- National Woman's Christian Temperance Union of Australia at The Encyclopedia of Women and Leadership in Twentieth-Century Australia

- Ruth Tibbits Tooze Papers, 1938-1940, at the Special Collections and Archives Research Center, Oregon State University Libraries

- Woman's Christian Temperance Union

- Temperance organizations in the United States

- Anti-abortion organizations in the United States

- Conservative organizations in the United States

- 1873 establishments in Ohio

- History of women in the United States

- Women's organizations based in the United States

- Christian women's organizations

- Organizations established in 1873

- Christianity and society in the United States

- International women's organizations

- Christian temperance movement

- Voter rights and suffrage organizations

- Temperance organizations in Canada

- Frances Willard