Vltava

| Vltava | |

|---|---|

The Vltava in Prague | |

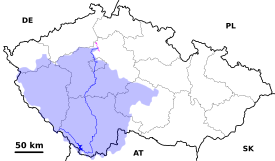

The course and drainage basin of the Vltava from its source to its confluence with the Elbe (magenta) | |

| Location | |

| Country | Czech Republic |

| Regions | |

| Cities | |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | Teplá Vltava |

| • location | Kvilda, Bohemian Forest |

| • coordinates | 48°58′29″N 13°33′39″E / 48.97472°N 13.56083°E |

| • elevation | 1,174 m (3,852 ft) |

| Mouth | |

• location | Elbe |

• coordinates | 50°20′29″N 14°28′30″E / 50.34139°N 14.47500°E |

• elevation | 156 m (512 ft) |

| Length | 431.3 km (268.0 mi) |

| Basin size | 28,089.9 km2 (10,845.6 sq mi) |

| Discharge | |

| • average | 149.9 m3/s (5,290 cu ft/s) near estuary |

| Basin features | |

| Progression | Elbe→ North Sea |

| Tributaries | |

| • left | Otava, Berounka |

| • right | Lužnice, Sázava |

| |

The Vltava (/ˈvʊltəvə, ˈvʌl-/ VU(U)L-tə-və,[1][2][3] Czech: [ˈvl̩tava] ⓘ; German: Moldau [ˈmɔldaʊ] ⓘ) is the longest river in the Czech Republic, a left tributary of the Elbe River. It runs southeast along the Bohemian Forest and then north across Bohemia, through Český Krumlov, České Budějovice, and Prague. It is commonly referred to as the "Czech national river".[4]

Etymology

[edit]Both the Czech name Vltava and the German name Moldau are believed to originate from the old Germanic words *wilt ahwa 'wild water' (compare Latin aqua).[5] In the Annales Fuldenses (872 AD) it is called Fuldaha; from 1113 AD it is attested as Wultha. In the Chronica Boemorum (1125 AD) it is attested for the first time in its Bohemian form, Wlitaua.[6]

Course

[edit]

The Vltava originates by a confluence of two rivers, the Teplá Vltava, which is longer, and the Studená Vltava, originating in Bavaria. From a water management point of view, the Vltava and Teplá Vltava are one river with single numbering of river kilometres. The Teplá Vltava originates in the territory of Kvilda in the Bohemian Forest at an elevation of 1,174 m (3,852 ft), on the slope of the Černá hora mountain. Together with the Teplá Vltava, the Vltava is 431.3 kilometres (268.0 mi) long. Without the Teplá Vltava, the Vltava is 377.0 kilometres (234.3 mi) long. The river flows north across Bohemia, through Český Krumlov, České Budějovice and Prague. It merges with the Elbe River at Mělník at an elevation of 156 m (512 ft). The height difference from source to mouth is 1,018 metres (3,340 ft).[7][8]

The Vltava River drains an area of 28,089.9 square kilometres (10,845.6 sq mi) in size, over half of Bohemia and about a third of the Czech Republic's entire territory.[9] The waters ultimately drain to the North Sea.

As it runs through Prague, the river is crossed by 18 bridges (including the Charles Bridge) and covers 31 kilometres (19 mi) within the city.[10] The water from the river was used for drinking until 1912 when the Vinohrady Water Tower ceased pumping operations, and is now a place to view the city.[11] It is, however, the source of drinking water in case of failures of or repairs to the water supply from the Želivka and Kárané sources. The Podolí water processing plant is on standby for such cases with the long section of the river upstream of the Podolí plant under the stricter, second degree of pollution prevention regulations.

Along its course, the river receives many tributaries. The longest tributaries of the Vltava are:[12]

| Tributary | Length (km) | River km | Side |

|---|---|---|---|

| Berounka | 244.6 | 63.4 | left |

| Sázava | 225.9 | 78.3 | right |

| Lužnice | 197.9 | 202.2 | right |

| Otava | 134.8 | 169.1 | left |

| Malše | 96.0 | 240.0 | right |

| Mastník | 49.5 | 104.6 | right |

| Kocába | 47.7 | 82.8 | left |

| Bakovský potok | 44.6 | 13.7 | left |

| Bezdrevský potok | 43.1 | 231.0 | left |

| Rokytka | 37.2 | 47.4 | right |

| Botič | 33.8 | 55.2 | right |

| Polečnice | 32.8 | 281.3 | left |

| Křemžský potok | 31.8 | 258.5 | left |

Navigation

[edit]

Between the confluence with the Elbe at Mělník and Prague, the river is navigable by vessels of up to 1,000 tonnes (980 long tons; 1,100 short tons) displacement. Most of the river upstream of Prague as far as České Budějovice is navigable by craft of up to 300 tonnes (300 long tons; 330 short tons) displacement, but such vessels cannot pass the dams at Orlík and Slapy, and are also restricted by a low bridge at Týn nad Vltavou. Work is planned to complete boat lifts, planned for but never completed, at the two dams, and to rebuild the bridge, in order for them to navigate throughout. Much smaller craft, of up to 3.5 tonnes (3.4 long tons; 3.9 short tons) displacement and under 3 metres (9.8 ft) beam and 3 metres (9.8 ft) air draft, can avoid these obstacles.[13]

Upstream of České Budějovice, the river's section around Český Krumlov (specifically from Vyšší Brod to Boršov nad Vltavou) is a very popular destination for water tourism.[14][15]

Dams

[edit]

Nine hydroelectric dams have been built on the Vltava south of Prague to regulate the water flow and generate hydroelectric power, starting in the 1930s. Beginning at the headwaters, these are: Lipno, Lipno II, Hněvkovice, Kořensko, Orlík, Kamýk, Slapy, Štěchovice and Vrané. The Orlík Reservoir supports the largest reservoir on the Vltava by volume, while the Lipno Reservoir retains the largest reservoir by area. The Štěchovice Reservoir is built over the site of St John's Rapids.

The river also features numerous weirs that help mitigate its flow from 1,172 metres (3,845 ft) in elevation at its source near the German border to 155 metres (509 ft) at its mouth in Mělník.

Floods

[edit]The Vltava basin has flooded multiple times throughout recorded history. Markers have been created along the banks denoting the water line for notable floods in 1784, 1845, 1890, 1940, and the highest of all in 2002.[16][17][18]

In August of 2002, the basin was heavily affected by the 2002 European floods when the flooded river killed several people and caused massive damage and disruption along its length, including in Prague. It left the oldest bridge in Prague, Charles Bridge, seriously weakened, requiring years of work to repair.[17]

Prague was again flooded in 2013. Many locations within the Vltava and Elbe basins were left under water, including the Prague Zoo, but metal barriers were erected along the banks of the Vltava to help protect the historic city centre.[19][20]

References in culture and science

[edit]In the classic narrative of the golem in Jewish folklore, the mystic Judah Loew ben Bezalel made the artificial giant "out of clay from the banks of the Vltava River and brought it to life through rituals and Hebrew incantations to defend the Prague ghetto from antisemitic attacks and pogroms."[21]

One of the best-known works of classical music by a Czech composer is Bedřich Smetana's Vltava, sometimes called The Moldau in English. It is from the Romantic era of classical music and is a musical description of the river's course through Bohemia.

Smetana's symphonic poem also inspired a song of the same name by Bertolt Brecht. An English version of it, by John Willett, features the lyrics Deep down in the Moldau the pebbles are shifting / In Prague three dead emperors moulder away.[22]

The Vltava River has been used as the setting for a number of films, including the 1942 Czech drama The Great Dam. More recently, the Vltava has been used as a film location for such films as Amadeus in 1984 and Mission: Impossible in 1996.

A minor planet, 2123 Vltava, discovered in 1973 by Soviet astronomer Nikolai Stepanovich Chernykh, is named after the river.[23]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Wells, John C. (2008), Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.), Longman, ISBN 9781405881180

- ^ "Vltava" (US) and "Vltava". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 2020-03-22.

- ^ "Vltava". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster. Retrieved March 31, 2019.

- ^ Mahoney, William (2001). The History of the Czech Republic and Slovakia. ABC-CLIO. p. 3. ISBN 0313363064.

- ^ Šmilauer, Vladimír (1946). "O jménech našich řek" [Names of our rivers]. Naše řeč (in Czech). 30 (9–10). Institute of the Czech Language: 161–165. ISSN 0027-8203.

- ^ "The Vltava River – Historical Communication Link in the Český Krumlov Region". Český Krumlov – UNESCO World Heritage. 2023. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

The length of its flow to the mouth of the river to the Labe River near Mělnik is 430.2 km. Down to Český Krumlov it has a catchment area of 1,339 km2, the whole basin of the Vltava river is 28,090 km2.

- ^ "Základní charakteristiky toku Vltava a jeho povodí" (in Czech). T. G. Masaryk Water Research Institute. Retrieved 2024-10-22.

- ^ "Základní charakteristiky toku Teplá Vltava a jeho povodí" (in Czech). T. G. Masaryk Water Research Institute. Retrieved 2024-10-22.

- ^ Complete table of the Bavarian Waterbody Register by the Bavarian State Office for the Environment (xls, 10.3 MB)

- ^ "About Prague". Avantgarde Prague. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

River Vltava (Moldau in German): It flows from south to north through the city for 31 kilometres, before joining the River Elbe near Prague. Nineteen bridges span the river.

- ^ "Prague Water Tower of Vinohrady, Hundred Years over the Vltava, virtual tour". Prague of the Centuries (in Czech). 2024. Retrieved 12 April 2024.

- ^ "Vodní toky". Evidence hlásných profilů (in Czech). Czech Hydrometeorological Institute. Retrieved 2024-10-22.

- ^ "Upper Vltava navigation inaugurated in May" (PDF). IWI news. Inland Waterways International. July 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 March 2020. Retrieved 3 March 2020.

- ^ Along the River Branna Nove Spoli - vltava-river.com

- ^ American in Prague (2018 webpage)

- ^ Papadaniil, Sofia; Schütze, Susann; Alukwe, Isaac (16 September 2007). "I. Flood Protection Measures of the City of Prague". Technische Universitat Dresden. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

Several flood marks along the river show the water levels of the different events in history and try to keep this danger of flooding in mind of the people.

- ^ a b Yates, Ricky (9 February 2010). "Flooding in Prague". Ricky Yates – an Anglican in Prague. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- ^ Yates, Ricky (15 April 2012). "The Vltava River". Ricky Yates – an Anglican in Prague. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- ^ "Thousands flee as central Europe flood waters rise". BBC News. 3 June 2013. Retrieved 3 June 2013.

- ^ "News". Radio Praha. 3 June 2013. Archived from the original on 2013-08-04. Retrieved 3 June 2013.

- ^ elisniv (2011-02-01). "The Golem in the Attic". Moment Magazine. Retrieved 2025-01-06.

- ^ "The song of the Moldau". Anti War Songs. 21 August 2012. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- ^ Schmadel, Lutz D. (2003). Dictionary of Minor Planet Names (5th ed.). New York: Springer Verlag. p. 172. ISBN 3-540-00238-3.

External links

[edit] Geographic data related to Vltava at OpenStreetMap

Geographic data related to Vltava at OpenStreetMap