Swami Vivekananda at the Parliament of the World's Religions

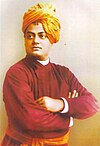

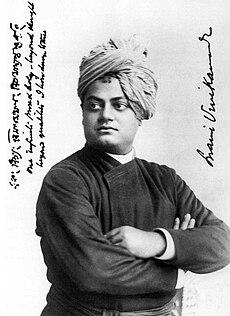

Vivekananda in Chicago in 1893 | |

| Date | 11–27 September 1893 |

|---|---|

| Location | Chicago, America |

| Outcome | A World Congress was organised in 2012 to commemorate 150th birth anniversary of Vivekananda |

| Website | parliamentofreligions.org |

Swami Vivekananda represented India and Hinduism at the Parliament of the World's Religions (1893). India celebrates National Youth Day on the birth anniversary of the great Swami.[1]

The first World's Parliament of Religions was held from 11 to 27 September 1893, with delegates from around the world participating.[2]

In 2012, a three-day world conference was organized to commemorate the 150th birth anniversary of Swami Vivekananda.[3]

Background

[edit]Journey to the west

[edit]With funds collected by his Madras disciples, the kings of Mysore, Ramnad, and Khetri, as well as diwans and other followers, Narendra left Mumbai for Chicago on 31 May 1893. He traveled under the name "Vivekananda," which was suggested by Ajit Singh of Khetri. The name "Vivekananda" means "the bliss of discerning wisdom."

Vivekananda began his journey to America from Bombay, India, on 31 May 1893, aboard the ship Peninsula.[4] His journey to America included stops in China, Japan, and Canada.

In Canton (Guangzhou), he visited several Buddhist monasteries. Afterward, he traveled to Japan, starting with Nagasaki. He then visited three more major cities before arriving in Osaka, Kyoto, and Tokyo. Finally, he reached Yokohama.

From Yokohama, he continued his journey to Canada aboard the ship RMS Empress of India.[5]

Meeting with Jamsetji Tata

[edit]During his journey from Yokohama to Canada aboard the RMS Empress of India, Vivekananda accidentally met Jamsetji Tata, who was also traveling to Chicago. Tata, a businessman who had made his initial fortune in the opium trade with China[6] and had established one of India's first textile mills, was on his way to Chicago to gather new business ideas.

In this fortuitous meeting, Vivekananda inspired Tata to establish a research and educational institution in India. They also discussed plans to set up a steel factory in the country.[5]

He reached Vancouver, Canada, on 25 July 1893.[5][7] From Vancouver, he traveled to Chicago by train and arrived there on Sunday, 30 July 1893.[8]

Journey to Boston

[edit]After reaching Chicago, Vivekananda learned that no one could attend the Parliament of the World's Religions as a delegate without proper credentials. As he did not have these at the time, he felt deeply disappointed. He also discovered that the Parliament would not begin until the first week of September.

Despite these challenges, Vivekananda did not lose hope. To reduce his expenses, he decided to travel to Boston, as it was less costly than staying in Chicago.

Meeting with John Henry Wright

[edit]In Boston, Vivekananda met Professor John Henry Wright of Harvard University, who invited him to deliver a lecture at the university. Impressed by Vivekananda's knowledge, wisdom, and eloquence, Professor Wright strongly encouraged him to represent Hinduism at the Parliament of the World's Religions.[9]

Vivekananda later wrote, "He urged upon me the necessity of going to the Parliament of Religions, which he thought would give an introduction to the nation."[4]

When Wright learned that Vivekananda lacked official accreditation and credentials to join the Parliament, he remarked, "To ask for your credentials is like asking the sun to state its right to shine in the heavens."[4]

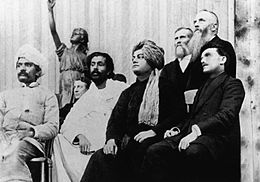

At the World's Parliament of Religions

[edit]The World's Parliament of Religions began on 11 September 1893 at the Permanent Memorial Art Palace (also known as the World's Congress Auxiliary Building), now the Art Institute of Chicago, as part of the World's Columbian Exposition.

Vivekananda delivered his first lecture on that day. His turn came in the afternoon, after much delay. Before stepping onto the stage, he bowed to Saraswati, the Hindu goddess of learning, and felt a surge of energy within him. He later described feeling as though someone or something else had taken over his body: "The Soul of India, the echo of the Rishis, the voice of Ramakrishna, the mouthpiece of the resurgent Time spirit."[4]

He began his speech with the iconic salutation, "Sisters and brothers of America!"

In his speech, Vivekananda sought to explain the root of disagreements between people, sects, and religions. He narrated a story of a frog, popularly known as the Koop Mandook (the frog in the well).

In the story, a frog lived in a well where it was born and raised. The frog believed that its well was the largest body of water in the world. One day, a frog from the sea visited the well. When the sea frog told the well frog that the sea was much larger than the well, the well frog refused to believe it and drove the sea frog away.

Vivekananda concluded:

That has been the difficulty all the while. I am a Hindu. I am sitting in my own little well and thinking that the whole world is my little well. The Christian sits in his little well and thinks the whole world is his well. The Muslim sits in his little well and thinks that is the whole world.

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (December 2012) |

Vivekananda gave a brief introduction to Hinduism and spoke on "The Meaning of the Hindu Religion." He discussed the three oldest religions in the world—Hinduism, Zoroastrianism, and Judaism—their endurance, and the emergence of Christianity.

He then elaborated on the principles of Vedanta philosophy, explaining the Hindu concepts of God, the soul, and the body.

Swami Vivekananda's famous speech at the Parliament of the World's Religions on 19 September 1893 is a historic and impactful moment in the history of Hinduism and interfaith dialogue. Delivered over a century ago, this speech is in the public domain, meaning it can be freely accessed and used without copyright restrictions.

In this brief address, Vivekananda offered a "little criticism" and stated that religion was not the most pressing need of Indians at that time. He expressed regret over the efforts of Christian missionaries attempting to save the souls of Indians, while poverty was a far more critical issue. He then explained that his aim in joining the Chicago Parliament of Religions was to seek aid for his impoverished people.

In this speech, Vivekananda discussed Buddhism, covering its origins, the relationship between Buddhism and Brahmanism, and the connection between Buddhism and the Vedas. He concluded, "Hinduism cannot live without Buddhism, nor Buddhism without Hinduism," emphasizing how Buddhism is the fulfillment of Hinduism.

This was Vivekananda's final address at the Parliament of the World's Religions. In his last speech, he stated that the Parliament had become an accomplished fact. He thanked the "noble souls" who had organized the event, which he felt "proved to the world that holiness, purity, and charity are not the exclusive possessions of any church in the world, and that every system has produced men and women of the most exalted character."

He concluded his speech with an appeal: "Help and not fight," "Assimilation and not destruction," "Harmony and peace and not dissension."

Impact

[edit]Parliament of the World's Religions (2012)

[edit]In 2012, a three-day world conference was organized by the Institute of World Religions (Washington Kali Temple) in Burtonsville, Maryland, in association with the Council for a Parliament of World Religions, Chicago, Illinois, to commemorate the 150th birth anniversary of Vivekananda.[10]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Yuva Yodha Book by Vikas chandak

- ^ Swami Vivekananda; Dave DeLuca (14 April 2006). Pathways to Joy: The Master Vivekananda on the Four Yoga Paths to God. New World Library. pp. 251–. ISBN 978-1-930722-67-5. Retrieved 17 December 2012.

- ^ "World Congress of Religions 2012". Parliament of the World's Religions. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- ^ a b c d P. R. Bhuyan (1 January 2003). Swami Vivekananda: Messiah of Resurgent India. Atlantic Publishers & Dist. pp. 16–. ISBN 978-81-269-0234-7. Retrieved 17 December 2012.

- ^ a b c Niranjan Rajadhyaksha (5 December 2006). The Rise of India: Its Transformation from Poverty to Prosperity. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 30–. ISBN 978-0-470-82201-2. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- ^ Huggler, Justin (1 February 2007). "From Parsee priests to profits: say hello to Tata". The Independent. Archived from the original on 26 May 2022. Retrieved 27 December 2012.

- ^ "Swami Vivekananda chronology" (PDF). Vedanta.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 17 December 2012.

- ^ Chaturvedi Badrinath (1 June 2006). Swami Vivekananda: The Living Vedanta. Penguin Books India. pp. 158–. ISBN 978-0-14-306209-7. Retrieved 17 December 2012.

- ^ G. S Banhatti (1 January 1995). Life And Philosophy Of Swami Vivekananda. Atlantic Publishers & Dist. pp. 27–. ISBN 978-81-7156-291-6. Retrieved 17 December 2012.

- ^ "World Congress of Religions 2012". Parliament of the World's Religions. Archived from the original on 28 September 2013. Retrieved 28 September 2013.