Multivitamin

A multivitamin is a preparation intended to serve as a dietary supplement with vitamins, dietary minerals, and other nutritional elements. Such preparations are available in the form of tablets, capsules, pastilles, powders, liquids, gummies, or injectable formulations. Other than injectable formulations, which are only available and administered under medical supervision, multivitamins are recognized by the Codex Alimentarius Commission (the United Nations' authority on food standards) as a category of food.[1]

In healthy people, most scientific evidence indicates that multivitamin supplements do not prevent cancer, heart disease, or other ailments, and regular supplementation is not necessary.[2][3][4][5][6][7][8] However, specific groups of people may benefit from multivitamin supplements, for example, people with poor nutrition or those at high risk of macular degeneration,[3][9] and women who are pregnant or trying to get pregnant.[10]

There is no standardized scientific definition for multivitamin.[11] In the United States, a multivitamin/mineral supplement is defined as a supplement containing three or more vitamins and minerals that does not include herbs, hormones, or drugs, where each vitamin and mineral is included at a dose below the tolerable upper intake level as determined by the Food and Drug Board, and does not present a risk of adverse health effects.[12]

Products and components

[edit]Many multivitamin formulas contain vitamin C, B1, B2, B3, B5, B6, B7, B9, B12, A, E, D2 (or D3), K, potassium, iodine, selenium, borate, zinc, calcium, magnesium, manganese, molybdenum, beta carotene, and/or iron. Multivitamins are typically available in a variety of formulas based on age and sex, or (as in prenatal vitamins) based on more specific nutritional needs; a multivitamin for men might include less iron, while a multivitamin for seniors might include extra vitamin D. Some formulas make a point of including extra antioxidants.

Some nutrients, such as calcium and magnesium, are rarely included at 100% of the recommended allowance because the pill would become too large in size. Most multivitamins come in capsule form; tablets, powders, liquids, and injectable formulations also exist. In the United States, the FDA requires any product marketed as a "multivitamin" to contain at least three vitamins and minerals; furthermore, the dosages must be below a "tolerable upper limit", and a multivitamin may not include herbs, hormones, or drugs.[13]

Uses

[edit]For certain people, particularly for older people, supplementing the diet with additional vitamins and minerals can have health impacts; however, the majority will not benefit.[14] People with dietary imbalances may include those on restrictive diets and those who cannot or will not eat a nutritious diet. Pregnant women and elderly adults have different nutritional needs compared to other adults, and a multivitamin may be indicated by a physician. Generally, medical advice is to avoid multivitamins during pregnancy, particularly those containing vitamin A, unless they are recommended by a health care professional. However, the NHS recommends 10μg of Vitamin D per day throughout the pregnancy and while breastfeeding, and 400μg of folic acid during the first trimester (first 12 weeks of pregnancy).[15] Some women may need to take iron, vitamin C, or calcium supplements during pregnancy, but only on the advice of a doctor.

In the 1999–2000 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 52% of adults in the United States reported taking at least one dietary supplement in the last month and 35% reported regular use of multivitamin - multimineral supplements. Women versus men, older adults versus younger adults, non-Hispanic whites versus non-Hispanic blacks, and those with higher education levels versus lower education levels (among other categories) were more likely to take multivitamins. Individuals who use dietary supplements (including multivitamins) generally report higher dietary nutrient intakes and healthier diets. Additionally, adults with a history of prostate and breast cancers were more likely to use dietary and multivitamin supplements.[16]

Precautions

[edit]

The amounts of each vitamin type in multivitamin formulations are generally adapted to correlate with what is believed to result in optimal health effects in large population groups. However, these standard amounts may not correlate with what is optimal in certain subpopulations, such as in children, pregnant women and people with certain medical conditions and medication.

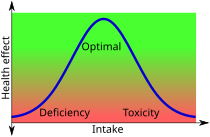

The health benefit of vitamins generally follows a biphasic dose-response curve, taking the shape of a bell curve, with the area in the middle being the safe-intake range and the edges representing deficiency and toxicity.[17] For example, the Food and Drug Administration recommends that adults on a 2,000 calorie diet get between 60 and 90 milligrams of vitamin C per day.[18] This is the middle of the bell curve. The upper limit is 2,000 milligrams per day for adults, which is considered potentially dangerous.[19]

In particular, pregnant women should consult their doctors before taking any multivitamins. For example, either an excess or deficiency of vitamin A can cause birth defects.[20]

Long-term use of beta-carotene, vitamin A, and vitamin E supplements may shorten life,[2] and increase the risk of lung cancer in people who smoke (especially those smoking more than 20 cigarettes per day), former smokers, people exposed to asbestos, and those who use alcohol.[21] Many common brand supplements in the United States contain levels above the DRI/RDA amounts for some vitamins or minerals.

Severe vitamin and mineral deficiencies require medical treatment and can be very difficult to treat with common over-the-counter multivitamins. In such situations, special vitamin or mineral forms with much higher potencies are available, either as individual components or as specialized formulations.

Multivitamins in large quantities may pose a risk of an acute overdose due to the toxicity of some components, principally iron. However, in contrast to iron tablets, which can be lethal to children,[22] toxicity from overdoses of multivitamins are very rare.[23] There appears to be little risk to supplement users of experiencing acute side effects due to excessive intakes of micronutrients.[24] There also are strict limits on the retinol content for vitamin A during pregnancies that are specifically addressed by prenatal formulas.

As noted in dietary guidelines from Harvard School of Public Health in 2008, multivitamins should not replace healthy eating or make up for unhealthy eating.[25][failed verification] In 2015, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force analyzed studies that included data for about 450,000 people. The analysis found no clear evidence that multivitamins prevent cancer or heart disease, helped people live longer, or "made them healthier in any way."[26]

Research

[edit]Provided that precautions are taken (such as adjusting the vitamin amounts to what is believed to be appropriate for children, pregnant women or people with certain medical conditions), multivitamin intake is generally safe, but research is still ongoing with regard to what health effects multivitamins have.

Evidence of health effects of multivitamins comes largely from prospective cohort studies, which evaluate health differences between groups that take multivitamins and groups that do not. Correlations between multivitamin intake and health found by such studies may not result from multivitamins themselves, but may reflect underlying characteristics of multivitamin-takers. For example, it has been suggested that multivitamin-takers may, overall, have more underlying diseases (making multivitamins appear as less beneficial in prospective cohort studies).[27] On the other hand, it has also been suggested that multivitamin users may, overall, be more health-conscious (making multivitamins appear as more beneficial in prospective cohort studies).[28][29] Randomized controlled studies have been encouraged to address this uncertainty.[30]

Cohort studies

[edit]

In February 2009, a study conducted in 161,808 postmenopausal women from the Women's Health Initiative clinical trials concluded that after eight years of follow-up "multivitamin use has little or no influence on the risk of common cancers, cardiovascular disease, or total mortality".[29] Another 2010 study in the Journal of Clinical Oncology suggested that multivitamin use during chemotherapy for stage III colon cancer had no effect on the outcomes of treatment.[31] A very large prospective cohort study published in 2011, including more than 180,000 participants, found no significant association between multivitamin use and mortality from all causes. The study also found no impact of multivitamin use on the risk of cardiovascular disease or cancer.[32]

A cohort study that received widespread media attention[33][34] is the Physicians' Health Study II (PHS-II).[35] PHS-II was a double-blind study of 14,641 male U.S. physicians initially aged 50 years or older (mean age of 64.3) that ran from 1997 to June 1, 2011. The mean time that the men were followed was 11 years. The study compared total cancer (excluding non-melanoma skin cancer) for participants taking a daily multivitamin (Centrum Silver by Pfizer) versus a placebo. Compared with the placebo, men taking a daily multivitamin had a small but statistically significant reduction in their total incidence of cancer. In absolute terms, the difference was just 1.3 cancer diagnoses per 1000 years of life. The hazard ratio for cancer diagnosis was 0.92 with a 95% confidence interval spanning 0.86–0.998 (P = .04); this implies a benefit of between 14% and .2% over placebo in the confidence interval. No statistically significant effects were found for any specific cancers or for cancer mortality. As pointed out in an editorial in the same issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association, the investigators observed no difference in the effect whether the study participants were or were not adherent to the multivitamin intervention, which diminishes the dose–response relationship.[36] The same editorial argued that the study did not properly address the multiple comparisons problem, in that the authors neglected to fully analyze all 28 possible associations in the study—they argue if this had been done, the statistical significance of the results would be lost.[36]

Using the same PHS-II study, researchers concluded that taking a daily multivitamin did not have any effect in reducing heart attacks and other major cardiovascular events, MI, stroke, and CVD mortality.[37]

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses

[edit]One major meta-analysis published in 2011, including previous cohort and case-control studies, concluded that multivitamin use was not significantly associated with the risk of breast cancer. It noted that one Swedish cohort study has indicated such an effect, but with all studies taken together, the association was not statistically significant.[30] A 2012 meta-analysis of ten randomized, placebo-controlled trials published in the Journal of Alzheimer's Disease found that a daily multivitamin may improve immediate recall memory, but did not affect any other measure of cognitive function.[38]

Another meta-analysis, published in 2013, found that multivitamin-multimineral treatment "has no effect on mortality risk",[39] and a 2013 systematic review found that multivitamin supplementation did not increase mortality and might slightly decrease it.[40] A 2014 meta-analysis reported that there was "sufficient evidence to support the role of dietary multivitamin/mineral supplements for the decreasing the risk of age-related cataracts."[41] A 2015 meta-analysis argued that the positive result regarding the effect of vitamins on cancer incidence found in Physicians' Health Study II (discussed above) should not be overlooked despite the neutral results found in other studies.

Looking at 2012 data, a study published in 2018 presented meta-analyses on cardiovascular disease outcomes and all-cause mortality. It found that "conclusive evidence for the benefit of any supplement across all dietary backgrounds (including deficiency and sufficiency) was not demonstrated; therefore, any benefits seen must be balanced against possible risks." The study dismissed the benefits of routinely taking supplements of vitamins C and D, beta-carotene, calcium, and selenium. Results indicated taking niacin may actually be harmful.[4][5]

In July 2019, another meta-analysis of 24 interventions in 277 trials was conducted and published in Annals of Internal Medicine, including a total of almost 1,000,000 participants.[7] The study generally concluded that the vast majority of multivitamins had no significant effect on survival or heart attack risk.[42] The study found a significant effect on heart health in a low-salt diet, and a small effect due to omega-3 and folic acid supplements.[43] This analysis supports the results of two early 2018 studies that found no conclusive benefits from multivitamins for healthy adults.[6][44]

Expert bodies

[edit]A 2006 report by the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality concluded that "regular supplementation with a single nutrient or a mixture of nutrients for years has no significant benefits in the primary prevention of cancer, cardiovascular disease, cataract, age-related macular degeneration or cognitive decline."[9] However, the report noted that multivitamins have beneficial effects for certain sub-populations, such as people with poor nutritional status, that vitamin D and calcium can help prevent fractures in older people, and that zinc and antioxidants can help prevent age-related macular degeneration in high-risk individuals.[9] A 2017 Cochrane Systematic Review found that multivitamins including vitamin E or beta carotene will not delay the onset of macular degeneration or prevent the disease,[45] however, some people with macular degeneration may benefit from multivitamin supplementation as there is evidence that it may delay the progression of the disease.[46][needs update] Including lutein and zeaxanthin supplements in with a multivitamin does not improve progression of macular degeneration.[46] The need for high-quality studies looking at the safety of taking multivitamins has been highlighted.[46]

According to the Harvard School of Public Health: "... many people don't eat the healthiest of diets. That's why a multivitamin can help fill in the gaps, and may have added health benefits."[47] The U.S. Office of Dietary Supplements, a branch of the National Institutes of Health, suggests that multivitamin supplements might be helpful for some people with specific health problems (for example, macular degeneration). However, the Office concluded that "most research shows that healthy people who take an MVM [multivitamin] do not have a lower chance of diseases, such as cancer, heart disease, or diabetes. Based on current research, it's not possible to recommend for or against the use of MVMs to stay healthier longer."[3]

Life expectancy

[edit]A 2024 study of 390,124 healthy adults found that use of multivitamins did not extend life expectancy.[48]

History and debate

[edit]The history of multivitamins begins in the early 20th century when advancements in nutritional science led to the discovery of essential vitamins and minerals. Initially, multivitamins were designed to respond to widespread nutritional deficiencies.[49] These supplements were seen as a practical solution to combat malnutrition, improving public health by providing vital nutrients that were otherwise scarce.

As the 20th century progressed, the use of multivitamins expanded beyond addressing deficiencies. With the rise of the wellness industry,[50] they became popularized as a convenient way to enhance overall health, even for those with access to sufficient nutrition. However, as marketing strategies evolved, the emphasis shifted from necessity to preventative health and general well-being,[51] often without sound scientific backing.

The role of multivitamins has since been increasingly questioned. Some still view them as beneficial, especially in cases of specific deficiencies. A growing body of research suggests that for many people, multivitamins act more as a placebo than a necessary supplement. This indicates a shift in the epistemology of vitamins, where people are generally more aware of them and their properties but there is a gap in their knowledge of the scientific research surrounding them

Studies have shown that multivitamins can have positive effects on mood and energy,[52][53] but there is little evidence to support an increase in general health and life expectancy.[54][55]

Under the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (DSHEA), passed in 1994 in the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is not responsible for testing the risks and efficacy of dietary supplements. Manufacturers are not required to present data on the effectiveness of multivitamins or disclose known side effects to the FDA. Furthermore, manufacturers are not required to test human safety of dietary supplements.[56]

Ethnographic research

[edit]Ethnographic research has investigated possible reasons behind the widespread use of multivitamins in societies where scientific knowledge is dominant, despite the limited empirical evidence supporting new products.[57][50] The findings reveal various socio-cultural factors contributing to their common use, including:

- Harm reduction: The cultural belief that multivitamins can mitigate risks associated with unhealthy lifestyles, conventional medicines, deficient diets, harmful environmental influences, or genetic predispositions.[57]

- Personal agency: The desire to gain control over one’s body and well-being.[57][50]

- Social proof: The perception of multivitamins’ effectiveness based on the experiences and behavior of friends, family and community members.[57][50]

- Social belonging: Marketing strategies that promote identity-building by targeting specific age groups, genders, or personal interests.[50]

- Biopolitics: The pursuit of productivity and reliability, as framed by capitalist societal expectations.[57]

From anthropological and psychological perspectives, the widespread consumption of multivitamins can be seen as an example of 'magical thinking,' a form of reasoning that seeks to explain phenomena through non-scientific means, distinct from 'irrational thinking’.[57][58]

ASD Research

[edit]In 2019, a systematic review and meta-analysis examining the relationship between ‘maternal multivitamin supplementation’ and children being diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) was published in Nutritional Research. The research was conducted in the previous year and involved using the ‘random effects’ model on 9 independent trials consisting of 231,163 children across 4459 cases. The results of this study indicated that pregnant women using multivitamin supplements during the prenatal period reduced the risk of their children being diagnosed with autism compared to their counterparts. Furthermore, the systematic review and meta-analysis found that women who took multivitamins prior to becoming pregnant saw a further reduced risk. The authors recommend further study.[59]

In 2021, a similar systematic review and meta-analysis examining the relationship between prenatal multivitamins and children being diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) was published in Nutrients. The study involved 904,947 children encompassing 8159 cases. The study concluded that while no distinct association was found, there was substantial evidence of reduced risk in high quality studies, multivitamin use during early pregnancy, tested prospective studies and evidence following the removal of a single outlier study.[60]

Regulations

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (March 2009) |

United States

[edit]The first person to formulate vitamins in the US was Dr. Forrest C. Shaklee.[61] Shaklee introduced a product he dubbed "Shaklee's Vitalized Minerals" in 1915, which he sold until adopting the now ubiquitous term "vitamin" in 1929.[62]

Because of their categorization as a dietary supplement by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), most multivitamins sold in the U.S. are not required to undergo the testing procedures typical of pharmaceutical drugs. However, some multivitamins contain very high doses of one or several vitamins or minerals, or are specifically intended to treat, cure, or prevent disease, and therefore require a prescription or medicinal license in the U.S. Since such drugs contain no new substances, they do not require the same testing as would be required by a New Drug Application, but were allowed on the market as drugs due to the Drug Efficacy Study Implementation program.[63]

Australia

[edit]Vitamins are classed as low-risk medications by the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA), and are therefore not assessed for efficacy, unlike most medicines sold in Australia. They require that the product is safe and that claims of efficacy can only be made in regards to minor ailments. No claims can be made about serious conditions. The TGA does not examine the contents of the product and whether it is what the label says it is, but they claim to carry out "targeted and random surveillance of products on the market."[64] They encourage people to report any unsafe products to them.

The TGA, however, has been criticized, by people such as Allan Asher, a regulatory expert and former deputy chair of the Australian Competition & Consumer Commission, for allowing more than a thousand types of claim, 86% of which are not supported by scientific evidence, including "softens hardness", "replenishes gate of vitality" and "moistens dryness in the triple burner".[65]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Guidelines for Vitamin and Mineral Food Supplements" (PDF). 2005. CAC/GL 55 - 2005. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-04-25. Retrieved 2019-10-06.

- ^ a b Bjelakovic G, Nikolova D, Gluud LL, Simonetti RG, Gluud C (March 2012). "Antioxidant supplements for prevention of mortality in healthy participants and patients with various diseases". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012 (3): CD007176. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007176.pub2. hdl:10138/136201. PMC 8407395. PMID 22419320.

- ^ a b c "Dietary Supplement Fact Sheet: Multivitamin/mineral Supplements". Office of Dietary Supplements, National Institutes of Health. Archived from the original on February 18, 2012. Retrieved March 2, 2012.

- ^ a b Litman RS (June 5, 2018). "New study on supplemental vitamins proves they're useless and a waste of money". Philly.com. Archived from the original on July 9, 2018. Retrieved July 9, 2018.

- ^ a b Jenkins DJ, Spence JD, Giovannucci EL, Kim YI, Josse R, Vieth R, et al. (June 2018). "Supplemental Vitamins and Minerals for CVD Prevention and Treatment". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 71 (22): 2570–2584. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2018.04.020. PMID 29852980.

- ^ a b Angelo G, Drake VJ, Frei B (18 June 2014). "Efficacy of Multivitamin/mineral Supplementation to Reduce Chronic Disease Risk: A Critical Review of the Evidence from Observational Studies and Randomized Controlled Trials". Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 55 (14): 1968–1991. doi:10.1080/10408398.2014.912199. PMID 24941429. S2CID 19463847.

- ^ a b Khan SU, Khan MU, Riaz H, Valavoor S, Zhao D, Vaughan L, et al. (August 2019). "Effects of Nutritional Supplements and Dietary Interventions on Cardiovascular Outcomes: An Umbrella Review and Evidence Map". Annals of Internal Medicine. 171 (3): 190–198. doi:10.7326/M19-0341. PMC 7261374. PMID 31284304.

- ^ "An Untold Truth of Vitamins". Healthyfiy. Archived from the original on 20 October 2020. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- ^ a b c Huang HY, Caballero B, Chang S, Alberg A, Semba R, Schneyer C, et al. (May 2006). "Multivitamin/mineral supplements and prevention of chronic disease" (PDF). Evidence Report/Technology Assessment (139): 1–117. PMC 4781083. PMID 17764205. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-09-16.

- ^ "Nutritional interventions update: multiple micronutrient supplements during pregnancy". www.who.int. Retrieved 2024-12-12.

- ^ Yetley EA (January 2007). "Multivitamin and multimineral dietary supplements: definitions, characterization, bioavailability, and drug interactions". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 85 (1): 269S – 276S. doi:10.1093/ajcn/85.1.269S. PMID 17209208.

- ^ National Institutes of Health State-of-the-Science Panel. National Institutes of Health State-of-the-Science Conference Statement: multivitamin/mineral supplements and chronic disease prevention" Am J Clin Nutr 2007;85:257S-64S

- ^ "How to Choose a Multivitamin Supplement". WebMD. Archived from the original on 22 July 2016. Retrieved 20 July 2016.

- ^ Dietary supplements: Using vitamin and mineral supplements wisely Archived 2013-10-12 at the Wayback Machine, Mayo Clinic

- ^ National Health Service. "Vitamins and nutrition in pregnancy". NHS Choices. NHS. Archived from the original on 10 January 2014. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- ^ Rock CL (January 2007). "Multivitamin-multimineral supplements: who uses them?". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 85 (1): 277S – 279S. doi:10.1093/ajcn/85.1.277S. PMID 17209209.

- ^ Combs GF (1998). The vitamins: Fundamental aspects in nutrition and health. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

- ^ "Vitamin and Mineral Recommendations". Council for Responsible Nutrition. Archived from the original on 2012-10-31. Retrieved 2017-10-01.. Retrieved 2011-03-30.

- ^ "Vitamin C (Ascorbic acid)". MedlinePlus. U.S. National Library of Medicine. 2010. Archived from the original on 5 October 2015. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- ^ Collins MD, Mao GE (1999). "Teratology of retinoids". Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology. 39: 399–430. doi:10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.39.1.399. PMID 10331090.

- ^ "Beta-Carotene". MedlinePlus. U.S. National Library of Medicine. 1 November 2017. Archived from the original on 26 December 2016. Retrieved 6 October 2019.

- ^ Cheney K, Gumbiner C, Benson B, Tenenbein M (1995). "Survival after a severe iron poisoning treated with intermittent infusions of deferoxamine". Journal of Toxicology. Clinical Toxicology. 33 (1): 61–66. doi:10.3109/15563659509020217. PMID 7837315.

- ^ Linakis JG, Lacouture PG, Woolf A (December 1992). "Iron absorption from chewable vitamins with iron versus iron tablets: implications for toxicity". Pediatric Emergency Care. 8 (6): 321–324. doi:10.1097/00006565-199212000-00003. PMID 1454637. S2CID 19636488.

- ^ Kiely M, Flynn A, Harrington KE, Robson PJ, O'Connor N, Hannon EM, et al. (October 2001). "The efficacy and safety of nutritional supplement use in a representative sample of adults in the North/South Ireland Food Consumption Survey". Public Health Nutrition. 4 (5A): 1089–1097. doi:10.1079/PHN2001190. PMID 11820922.

- ^ Harvard School of Public Health (2008). Food pyramids: What should you really eat?. Retrieved from http://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource Archived 2011-04-20 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Why You Don't Need A Multivitamin – Consumer Reports". Archived from the original on 2015-09-10. Retrieved 2015-09-10.

- ^ Li K, Kaaks R, Linseisen J, Rohrmann S (June 2012). "Vitamin/mineral supplementation and cancer, cardiovascular, and all-cause mortality in a German prospective cohort (EPIC-Heidelberg)" (PDF). European Journal of Nutrition. 51 (4): 407–413. doi:10.1007/s00394-011-0224-1. PMID 21779961. S2CID 1692747. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-12-17. Retrieved 2019-07-10.

- ^ Seddon JM, Christen WG, Manson JE, LaMotte FS, Glynn RJ, Buring JE, et al. (May 1994). "The use of vitamin supplements and the risk of cataract among US male physicians". American Journal of Public Health. 84 (5): 788–792. doi:10.2105/AJPH.84.5.788. PMC 1615060. PMID 8179050.

- ^ a b Neuhouser ML, Wassertheil-Smoller S, Thomson C, Aragaki A, Anderson GL, Manson JE, et al. (February 2009). "Multivitamin use and risk of cancer and cardiovascular disease in the Women's Health Initiative cohorts". Archives of Internal Medicine. 169 (3): 294–304. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2008.540. PMC 3868488. PMID 19204221.

- ^ a b Chan AL, Leung HW, Wang SF (April 2011). "Multivitamin supplement use and risk of breast cancer: a meta-analysis". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 45 (4): 476–484. doi:10.1345/aph.1P445. PMID 21487086. S2CID 22445157.

- ^ Ng K, Meyerhardt JA, Chan JA, Niedzwiecki D, Hollis DR, Saltz LB, et al. (October 2010). "Multivitamin use is not associated with cancer recurrence or survival in patients with stage III colon cancer: findings from CALGB 89803". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 28 (28): 4354–4363. doi:10.1200/JCO.2010.28.0362. PMC 2954134. PMID 20805450.

- ^ Park SY, Murphy SP, Wilkens LR, Henderson BE, Kolonel LN (April 2011). "Multivitamin use and the risk of mortality and cancer incidence: the multiethnic cohort study". American Journal of Epidemiology. 173 (8): 906–914. doi:10.1093/aje/kwq447. PMC 3105257. PMID 21343248.

- ^ Rabin RC (October 17, 2012). "Daily Multivitamin May Reduce Cancer Risk, Clinical Trial Finds". New York Times. Archived from the original on October 18, 2012. Retrieved October 17, 2012.

- ^ Winslow R (18 October 2012). "Multivitamin Cuts Cancer Risk, Large Study Finds". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 13 December 2012.

- ^ Gaziano JM, Sesso HD, Christen WG, Bubes V, Smith JP, MacFadyen J, et al. (November 2012). "Multivitamins in the prevention of cancer in men: the Physicians' Health Study II randomized controlled trial". JAMA. 308 (18): 1871–1880. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.14641. PMC 3517179. PMID 23162860.

- ^ a b Bach PB, Lewis RJ (November 2012). "Multiplicities in the assessment of multiple vitamins: is it too soon to tell men that vitamins prevent cancer?". JAMA. 308 (18): 1916–1917. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.53273. PMID 23150011.

- ^ Sesso HD, Christen WG, Bubes V, Smith JP, MacFadyen J, Schvartz M, et al. (November 2012). "Multivitamins in the prevention of cardiovascular disease in men: the Physicians' Health Study II randomized controlled trial". JAMA. 308 (17): 1751–1760. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.14805. PMC 3501249. PMID 23117775.

- ^ Grima NA, Pase MP, Macpherson H, Pipingas A (2012). "The effects of multivitamins on cognitive performance: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 29 (3): 561–569. doi:10.3233/JAD-2011-111751. PMID 22330823. S2CID 19767652.

- ^ Macpherson H, Pipingas A, Pase MP (February 2013). "Multivitamin-multimineral supplementation and mortality: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 97 (2): 437–444. doi:10.3945/ajcn.112.049304. hdl:10536/DRO/DU:30073126. PMID 23255568.

- ^ Alexander DD, Weed DL, Chang ET, Miller PE, Mohamed MA, Elkayam L (2013). "A systematic review of multivitamin-multimineral use and cardiovascular disease and cancer incidence and total mortality". Journal of the American College of Nutrition. 32 (5): 339–354. doi:10.1080/07315724.2013.839909. PMID 24219377. S2CID 24230868.

- ^ Zhao LQ, Li LM, Zhu H, The Epidemiological Evidence-Based Eye Disease Study Research Group EY (February 2014). "The effect of multivitamin/mineral supplements on age-related cataracts: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Nutrients. 6 (3): 931–949. doi:10.3390/nu6030931. PMC 3967170. PMID 24590236.

- ^ "Save Your Money: Vast Majority Of Dietary Supplements Don't Improve Heart Health or Put Off Death". Johns Hopkins Medicine. 2019-07-16. Archived from the original on 2019-07-25. Retrieved 25 July 2019.

- ^ Haridy R (2019-07-22). "Massive meta-study finds most vitamin supplements have no effect on lifespan or heart health". New Atlas. Archived from the original on 2019-07-25. Retrieved 25 July 2019.

- ^ Kim J, Choi J, Kwon SY, McEvoy JW, Blaha MJ, Blumenthal RS, et al. (July 2018). "Association of Multivitamin and Mineral Supplementation and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes. 11 (7): e004224. doi:10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.117.004224. PMID 29991644. S2CID 51615818.

- ^ Evans JR, Lawrenson JG (July 2017). "Antioxidant vitamin and mineral supplements for preventing age-related macular degeneration". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017 (7): CD000253. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000253.pub4. PMC 6483250. PMID 28756617.

- ^ a b c Evans JR, Lawrenson JG (July 2017). "Antioxidant vitamin and mineral supplements for slowing the progression of age-related macular degeneration". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 7 (7): CD000254. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000254.pub4. PMC 6483465. PMID 28756618.

- ^ "Vitamins". harvard.edu. 18 September 2012. Archived from the original on 23 March 2018. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- ^ Loftfield E, O'Connell CP, Abnet CC, Graubard BI, Liao LM, Beane Freeman LE, et al. (June 2024). "Multivitamin Use and Mortality Risk in 3 Prospective US Cohorts". JAMA Network Open. 7 (6): e2418729. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.18729. PMC 11208972. PMID 38922615.

- ^ Martini SA, Phillips M (September 2009). "Nutrition and food commodities in the 20th century". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 57 (18): 8130–8135. doi:10.1021/jf9000567. PMID 19719130.

- ^ a b c d e Nichter M, Thompson JJ (June 2006). "For my wellness, not just my illness: North Americans' use of dietary supplements". Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry. 30 (2): 175–222. doi:10.1007/s11013-006-9016-0. PMID 16841188.

- ^ Cardenas D, Fuchs-Tarlovsky V (June 2018). "Is multi-level marketing of nutrition supplements a legal and an ethical practice?". Clinical Nutrition ESPEN. 25: 133–138. doi:10.1016/j.clnesp.2018.03.118. PMID 29779808.

- ^ Sarris J, Cox KH, Camfield DA, Scholey A, Stough C, Fogg E, et al. (December 2012). "Participant experiences from chronic administration of a multivitamin versus placebo on subjective health and wellbeing: a double-blind qualitative analysis of a randomised controlled trial". Nutrition Journal. 11 (1): 110. doi:10.1186/1475-2891-11-110. PMC 3545984. PMID 23241329.

- ^ Harris E, Kirk J, Rowsell R, Vitetta L, Sali A, Scholey AB, et al. (December 2011). "The effect of multivitamin supplementation on mood and stress in healthy older men". Human Psychopharmacology. 26 (8): 560–567. doi:10.1002/hup.1245. PMID 22095836.

- ^ Pocobelli G, Peters U, Kristal AR, White E (August 2009). "Use of supplements of multivitamins, vitamin C, and vitamin E in relation to mortality". American Journal of Epidemiology. 170 (4): 472–483. doi:10.1093/aje/kwp167. PMC 2727181. PMID 19596711.

- ^ Macpherson H, Pipingas A, Pase MP (February 2013). "Multivitamin-multimineral supplementation and mortality: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 97 (2): 437–444. doi:10.3945/ajcn.112.049304. hdl:10536/DRO/DU:30073126. PMID 23255568.

- ^ Dodge T (2016). "Consumers' perceptions of the dietary supplement health and education act: implications and recommendations". Drug Testing and Analysis. 8 (3–4): 407–409. doi:10.1002/dta.1857. PMID 27072844.

- ^ a b c d e f McCabe M, Fabri A (April 2012). "Vitamin Practices and Ideologies of Health and the Body". International Journal of Business Anthropology. 3 (1). doi:10.33423/ijba.v3i1.1170. ISSN 2155-6237.

- ^ Taylor M (2013-08-01). The Oxford Handbook of the Development of Imagination. Oxford Library of Psychology. ISBN 9780199983032.

- ^ Guo BQ, Li HB, Zhai DS, Ding SB (May 2019). "Maternal multivitamin supplementation is associated with a reduced risk of autism spectrum disorder in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Nutrition Research. 65: 4–16. doi:10.1016/j.nutres.2019.02.003. PMID 30952506.

- ^ Friel C, Leyland AH, Anderson JJ, Havdahl A, Borge T, Shimonovich M, et al. (July 2021). "Prenatal Vitamins and the Risk of Offspring Autism Spectrum Disorder: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Nutrients. 13 (8): 2558. doi:10.3390/nu13082558. PMC 8398897. PMID 34444717.

- ^ Longden T (27 January 2008). "Famous Iowans: Forrest Shaklee". The Des Moines Register.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Shook RL (July 1982). The Shaklee Story (1st ed.). New York City, NY: Harper Collins. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-06-015005-1.

- ^ See 36 Fed. Reg. 6843 (Apr. 9, 1971).

- ^ "Watched Vitamania? Here's how the TGA regulates vitamins in Australia". Therapeutic Goods Administration. 2018-08-14. Archived from the original on 2019-01-19. Retrieved 17 January 2019.

- ^ "'Softens hardness': TGA under fire for health claim list that critics say endorses pseudoscience". Sydney Morning Herald. 2018-02-08. Archived from the original on 2019-01-19. Retrieved 17 January 2019.

External links

[edit]- Dietary Supplement Fact Sheet: Multivitamin/mineral Supplements, from the U.S. National Institutes of Health

- Safe upper levels for vitamins and minerals – Report of the UK Food Standards Agency Expert Group on Vitamins and Minerals