Andreas Vesalius

Andreas Vesalius | |

|---|---|

Portrait by Jan van Calcar | |

| Born | Andries van Wezel 31 December 1514 |

| Died | 15 October 1564 (aged 49) |

| Education | University of Leuven (M.D., 1537) University of Paris |

| Known for | De humani corporis fabrica (On the Fabric of the Human Body) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Anatomy |

| Institutions | University of Padua (1537–1542) |

| Thesis | Paraphrasis in nonum librum Rhazae medici Arabis clarissimi ad regem Almansorem, de affectuum singularum corporis partium curatione (1537) |

| Academic advisors | Johann Winter von Andernach[1] Jacques Dubois[1] Jean Fernel[1] |

| Notable students | John Caius Realdo Colombo |

Andries van Wezel (31 December 1514 – 15 October 1564), latinised as Andreas Vesalius (/vɪˈseɪliəs/),[2][a] was an anatomist and physician who wrote De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem (On the fabric of the human body in seven books), which is considered one of the most influential books on human anatomy and a major advance over the long-dominant work of Galen. Vesalius is often referred to as the founder of modern human anatomy. He was born in Brussels, which was then part of the Habsburg Netherlands. He was a professor at the University of Padua (1537–1542) and later became Imperial physician at the court of Emperor Charles V.

Early life and education

[edit]Vesalius was born as Andries van Wesel to his father Anders van Wesel and mother Isabel Crabbe on 31 December 1514 in Brussels, which was then part of the Habsburg Netherlands. His great-grandfather, Jan van Wesel, probably born in Wesel, received a medical degree from the University of Pavia and taught medicine at the University of Leuven. His grandfather, Everard van Wesel, was the Royal Physician of Emperor Maximilian, whilst his father, Anders van Wesel, served as apothecary to Maximilian and later valet de chambre to his successor, Charles V. Anders encouraged his son to continue in the family tradition and enrolled him in the Brethren of the Common Life in Brussels to learn Greek and Latin prior to learning medicine, according to standards of the era.[3]

In 1528 Vesalius entered the University of Leuven (Pedagogium Castrense) taking arts, but when his father was appointed as the Valet de Chambre in 1532 he decided instead to pursue a career in medicine at the University of Paris, where he moved in 1533. There he studied the theories of Galen under the auspices of Johann Winter von Andernach, Jacques Dubois (Jacobus Sylvius) and Jean Fernel. It was during that time that he developed an interest in anatomy and was often found examining excavated bones in the charnel houses at the Cemetery of the Innocents.[4] He is said to have constructed his first skeleton by stealing from a gibbet.[5][4][6]

Vesalius was forced to leave Paris in 1536 owing to the opening of hostilities between the Holy Roman Empire and France and returned to the University of Leuven. He completed his studies there and graduated the following year. His doctoral thesis, Paraphrasis in nonum librum Rhazae medici Arabis clarissimi ad regem Almansorem, de affectuum singularum corporis partium curatione, was a commentary on the ninth book of Rhazes.

Medical career and accomplishments

[edit]On the day of his graduation he was immediately offered the chair of surgery and anatomy (explicator chirurgiae) at the University of Padua. He also guest-lectured at the University of Bologna and the University of Pisa. Prior to taking up his position in Padua, Vesalius traveled through Italy and assisted the future Pope Paul IV and Ignatius of Loyola to heal those afflicted by leprosy. In Venice he met the illustrator Johan van Calcar, a student of Titian. It was with van Calcar that Vesalius published his first anatomical text, Tabulae Anatomicae Sex, in 1538.[7] Previously these topics had been taught primarily from reading classical texts, mainly Galen, followed by an animal dissection by a barber–surgeon whose work was directed by the lecturer.[8] No attempt was made to confirm Galen's claims, which were considered unassailable. Vesalius, in contrast, performed dissection as the primary teaching tool, handling the actual work himself and urging students to perform dissection themselves. He considered hands-on direct observation to be the only reliable resource.

Vesalius created detailed illustrations of anatomy for students in the form of six large woodcut posters. When he found that some of them were being widely copied, he published them all in 1538 under the title Tabulae anatomicae sex. He followed this in 1539 with an updated version of Winter's anatomical handbook, Institutiones anatomicae.

In 1539 he also published his Venesection Epistle on bloodletting. This was a popular treatment for almost any illness, but there was some debate about where to take the blood from. The classical Greek procedure, advocated by Galen, was to collect blood from a site near the location of the illness. However the Muslim and medieval practice was to draw a smaller amount of blood from a distant location. Vesalius' pamphlet generally supported Galen's view but with qualifications that rejected the infiltration of Galen.

In Bologna, Vesalius discovered that all of Galen's research was restricted to animals, since the tradition of Rome did not allow dissection of the human body.[9] Galen had dissected Barbary macaques instead, which he considered structurally closest to man. Even though Galen was a qualified examiner, his research produced many errors owing to the limited anatomical material available to him.[10] Vesalius contributed to the new Giunta edition of Galen's collected works and began to write his own anatomical text based on his own research. Until Vesalius pointed out Galen's substitution of animal for human anatomy, it had gone unnoticed and had long been the basis of studying human anatomy.[8]

Unlike Galen, Vesalius was able to procure a steady supply of human cadavers for dissection. In 1539, a judge at the Padua criminal court had been interested by Vesalius' work and had agreed to regularly supply him the cadavers of executed criminals.[9][11]

Galen had assumed that arteries carried the purest blood to higher organs such as the brain and lungs from the left ventricle of the heart, while veins carried blood to the lesser organs such as the stomach from the right ventricle. In order for this theory to be correct, some kind of opening was needed to interconnect the ventricles, and Galen claimed to have found them. So paramount was Galen's authority that for 1400 years a succession of anatomists had claimed to find these holes, until Vesalius admitted he could not find them. Nonetheless, he did not venture to dispute Galen on the distribution of blood, being unable to offer any other solution, and so supposed that it diffused through the unbroken partition between the ventricles.[12]

Other famous examples of Vesalius disproving Galen's assertions were his discoveries that the lower jaw (mandible) was composed of only one bone, not two (which Galen had assumed based on animal dissection) and that humans lack the rete mirabile, a network of blood vessels at the base of the brain that is found in sheep and other ungulates.

In 1543, Vesalius conducted a public dissection of the body of Jakob Karrer von Gebweiler, a notorious felon from the city of Basel, Switzerland. He assembled and articulated the bones, finally donating the skeleton to the University of Basel. This preparation ("The Basel Skeleton") is Vesalius' only well-preserved skeletal preparation, and also the world's oldest surviving anatomical preparation. It is still displayed at the Anatomical Museum of the University of Basel.[13]

In the same year Vesalius took residence in Basel to help Johannes Oporinus publish the seven-volume De humani corporis fabrica (On the fabric of the human body), a groundbreaking work of human anatomy that he dedicated to Charles V. Many believe it was illustrated by Titian's pupil Jan Stephen van Calcar, but evidence is lacking, and it is unlikely that a single artist created all 273 illustrations in a period of time so short. At about the same time he published an abridged edition for students, Andrea Vesalii suorum de humani corporis fabrica librorum epitome, and dedicated it to Philip II of Spain, the son of the Emperor. That work, now collectively referred to as the Fabrica of Vesalius, was groundbreaking in the history of medical publishing and is considered to be a major step in the development of scientific medicine. Because of this, it marks the establishment of anatomy as a modern descriptive science.[14]

Though Vesalius' work was not the first such work based on actual dissection, nor even the first work of this era, the production quality, highly detailed and intricate plates, and the likelihood that the artists who produced it were clearly present in person at the dissections made it an instant classic. Pirated editions were available almost immediately, an event Vesalius acknowledged in a printer's note would happen. Vesalius was 28 years old when the first edition of Fabrica was published.

Imperial physician and death

[edit]

Soon after publication, Vesalius was invited to become imperial physician to the court of Emperor Charles V. He informed the Venetian Senate that he would leave his post at Padua, which prompted Duke Cosimo I de' Medici to invite him to move to the expanding university in Pisa, which he declined. Vesalius took up the offered position in the imperial court, where he had to deal with other physicians who mocked him for being a mere barber surgeon instead of an academic working on the respected basis of theory.

In the 1540s, shortly after entering in service of the emperor, Vesalius married Anne van Hamme, from Vilvorde, Belgium. They had one daughter, named Anne, who died in 1588.[15]

Over the next eleven years Vesalius traveled with the court, treating injuries caused in battle or tournaments, performing postmortems, administering medication, and writing private letters addressing specific medical questions. During these years he also wrote the Epistle on the China root, a short text on the properties of a medical plant whose efficacy he doubted, as well as a defense of his anatomical findings. This elicited a new round of attacks on his work that called for him to be punished by the emperor. In 1551, Charles V commissioned an inquiry in Salamanca to investigate the religious implications of his methods. Although Vesalius' work was cleared by the board, the attacks continued. Four years later one of his main detractors and one-time professors, Jacobus Sylvius, published an article that claimed that the human body itself had changed since Galen had studied it.[16]

In 1555, Vesalius became physician to Philip II,[11] and in the same year he published a revised edition of De humani corporis fabrica.

In 1564 Vesalius went on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land, some said, in penance after being accused of dissecting a living body. He sailed with the Venetian fleet under James Malatesta via Cyprus. When he reached Jerusalem he received a message from the Venetian senate requesting him again to accept the Paduan professorship, which had become vacant on the death of contemporary Fallopius.

After struggling for many days with adverse winds in the Ionian Sea, he was shipwrecked on the island of Zakynthos.[17] Here he soon died, in such debt that a benefactor kindly paid for his funeral. At the time of his death he was 49 years old. He was buried somewhere on the island of Zakynthos (Zante).[18]

For some time, it was assumed that Vesalius's pilgrimage was due to the pressures imposed on him by the Inquisition. Today, this assumption is generally considered to be without foundation[19] and is dismissed by modern biographers. It appears the story was spread by Hubert Languet, a diplomat under Emperor Charles V and then under the Prince of Orange, who claimed in 1565 that Vesalius had performed an autopsy on an aristocrat in Spain while the heart was still beating, leading to the Inquisition's condemning him to death. The story went on to claim that Philip II had the sentence commuted to a pilgrimage. That story re-surfaced several times, until it was more recently revised.

The decision to undertake the pilgrimage was likely just a pretext to leave the Spanish court. Its lifestyle did not please him and he longed to continue his research. Given that he could not get rid of his royal service by resignation, he managed to escape asking for the permission to go to Jerusalem.[20]

Publications

[edit]De Humani Corporis Fabrica

[edit]

In 1543, Vesalius asked Johannes Oporinus to publish the book De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem (On the fabric of the human body in seven books), a groundbreaking work of human anatomy he dedicated to Charles V and which many believe was illustrated by Titian's pupil Jan Stephen van Calcar.

About the same time he published another version of his great work, entitled De Humani Corporis Fabrica Librorum Epitome (Abridgement of the On the fabric of the human body) more commonly known as the Epitome, with a stronger focus on illustrations than on text, so as to help readers, including medical students, to easily understand his findings. The actual text of the Epitome was an abridged form of his work in the Fabrica, and the organization of the two books was quite varied. He dedicated it to Philip II of Spain, son of the Emperor.[21]

The Fabrica emphasized the priority of dissection and what has come to be called the "anatomical" view of the body, seeing human internal functioning as a result of an essentially corporeal structure filled with organs arranged in three-dimensional space. His book contains drawings of several organs on two leaves. This allows for the creation of three-dimensional diagrams by cutting out the organs and pasting them on flayed figures.[14] This was in stark contrast to many of the anatomical models used previously, which had strong Galenic/Aristotelean elements, as well as elements of astrology. Although modern anatomical texts had been published by Mondino and Berenger, much of their work was clouded by reverence for Galen and Arabian doctrines.

Besides the first good description of the sphenoid bone, he showed that the sternum consists of three portions and the sacrum of five or six, and described accurately the vestibule in the interior of the temporal bone. He not only verified Estienne's observations on the valves of the hepatic veins, but also described the vena azygos, and discovered the canal which passes in the fetus between the umbilical vein and the vena cava, since named the ductus venosus. He described the omentum and its connections with the stomach, the spleen and the colon; gave the first correct views of the structure of the pylorus; observed the small size of the caecal appendix in man; gave the first good account of the mediastinum and pleura and the fullest description of the anatomy of the brain up to that time. He did not understand the inferior recesses, and his account of the nerves is confused by regarding the optic as the first pair, the third as the fifth, and the fifth as the seventh.

In this work, Vesalius also becomes the first person to describe mechanical ventilation.[22] It is largely this achievement that has resulted in Vesalius being incorporated into the Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists college arms and crest.

Excerpts

[edit]When I undertake the dissection of a human pelvis I pass a stout rope tied like a noose beneath the lower jaw and through the zygomas up to the top of the head... The lower end of the noose I run through a pulley fixed to a beam in the room so that I may raise or lower the cadaver as it hangs there or turn around in any direction to suit my purpose; ... You must take care not to put the noose around the neck, unless some of the muscles connected to the occipital bone have already been cut away.[23]

Other publications

[edit]In 1538, Vesalius wrote Epistola, docens venam axillarem dextri cubiti in dolore laterali secandam (A letter, teaching that in cases of pain in the side, the axillary vein of the right elbow be cut), commonly known as the Venesection Letter, which demonstrated a revived venesection, a classical procedure in which blood was drawn near the site of the ailment. He sought to locate the precise site for venesection in pleurisy within the framework of the classical method. The real significance of the book is his attempt to support his arguments by the location and continuity of the venous system from his observations rather than appeal to earlier published works. With this novel approach to the problem of venesection, Vesalius posed the then striking hypothesis that anatomical dissection might be used to test speculation.

In 1546, three years after the Fabrica, he wrote his Epistola rationem modumque propinandi radicis Chynae decocti, commonly known as the Epistle on the China Root. Ostensibly an appraisal of a popular but ineffective treatment for gout, syphilis, and stones, this work is especially important as a continued polemic against Galenism and a reply to critics in the camp of his former professor Jacobus Sylvius, now an obsessive detractor.

In February 1561, Vesalius was given a copy of Gabriele Fallopio's Observationes anatomicae, friendly additions and corrections to the Fabrica. Before the end of the year Vesalius composed a cordial reply, Anatomicarum Gabrielis Fallopii observationum examen, generally referred to as the Examen. In this work he recognizes in Fallopio a true equal in the science of dissection he had done so much to create. Vesalius' reply to Fallopio was published in May 1564, a month after Vesalius' death on the Greek island of Zante (now called Zakynthos).

Scientific findings

[edit]Skeletal system

[edit]

- Vesalius believed the skeletal system to be the framework of the human body. It was in this opening chapter or book of De fabrica that Vesalius made several of his strongest claims against Galen's theories and writings which he had put in his anatomy books. In his extensive study of the skull, Vesalius claimed that the mandible consisted of one bone, whereas Galen had thought it to be two separate bones. He accurately described the vestibule in the interior of the temporal bone of the skull.

- In Galen's observation of the ape, he had discovered that their sternum consisted of seven parts which he assumed also held true for humans. Vesalius discovered that the human sternum consisted of only three parts.

- He also disproved the common belief that men had one rib fewer than women and noted that the fibula and tibia bones of the leg were indeed larger than the humerus bone of the arm, unlike Galen's original findings.

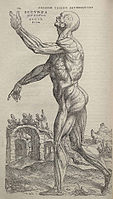

Muscular system

[edit]- One of Vesalius' contributions to the study of the muscular system is the illustrations that accompany the text in De fabrica, which would become known as the "muscle men". He describes the source and position of each muscle of the body and provides information on their respective operation.

Vascular and circulatory systems

[edit]- Vesalius' work on the vascular and circulatory systems was his greatest contribution to modern medicine. In his dissections of the heart, Vesalius became convinced that Galen's claims of a porous interventricular septum were false. This fact was previously described by Michael Servetus, a fellow of Vesalius, but never reached the public, for it was written down in the "Manuscript of Paris",[24] in 1546, and published later in his Christianismi Restitutio (1553), a book regarded as heretical by the Inquisition. Only three copies survived, but these remained hidden for decades, the rest having been burned shortly after publication. In the second edition Vesalius published that the septum was indeed waterproof, discovering (and naming), the mitral valve to explain the blood flow.

- Vesalius believed that cardiac systole is synchronous with the arterial pulse.

- He not only verified Estienne's findings on the valves of the hepatic veins, but also described the azygos vein, and discovered the canal which passes into the fetus between the umbilical vein and vena cava.

Nervous system

[edit]- Vesalius defined a nerve as the mode of transmitting sensation and motion and thus refuted his contemporaries' claims that ligaments, tendons and aponeuroses were three types of nerve units.

- He believed that the brain and the nervous system are the center of the mind and emotion in contrast to the common Aristotelian belief that the heart was the center of the body. He correspondingly believed that nerves themselves do not originate from the heart, but from the brain—facts already experimentally proved by Herophilus and Erasistratus in the classical era, but suppressed after the adoption of Aristotelianism by the Catholic Church in the Middle Ages.

- Upon studying the optic nerve, Vesalius came to the conclusion that nerves were not hollow.

Abdominal organs

[edit]- In De fabrica, he corrected an earlier claim he made in Tabulae about the right kidney being set higher than the left. Vesalius claimed that the kidneys were not a filter device for urine to pass through, but rather that the kidneys serve to filter blood as well, and that excretions from the kidneys travelled through the ureters to the bladder.

- He described the omentum, and its connections with the stomach, the spleen and the colon gave the first correct views of the structure of the pylorus.

- He also observed the small size of the caecal appendix in man and gave the first good account of the mediastinum and pleura.

- Vesalius admitted that due to a lack of pregnant cadavers he was unable to come to a significant understanding of the reproductive organs. However, he did find that the uterus had been falsely identified as having two distinct sections.

Heart

[edit]- Through his work with muscles, Vesalius believed that a criterion for muscles was their voluntary motion. On this claim, he deduced that the heart was not a true muscle due to the obvious involuntary nature of its motion.

- He identified two chambers and two atria. The right atrium was considered a continuation of the inferior and superior venae cavae, and the left atrium was considered a continuation of the pulmonary vein.

- He also addressed the controversial issue of the heart being the centre of the soul. He wished to avoid drawing any conclusions due to possible conflict with contemporary religious beliefs.

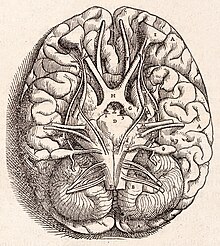

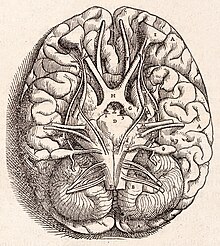

Base of the brain, showing the optic chiasma, cerebellum, olfactory bulbs, etc. - Against Galen's theory and many beliefs he also discovered that there was no hole in the septum or heart.

Other achievements

[edit]- Vesalius disproved Galen's assertion that men have more teeth than women.[17]

- Vesalius introduced the notion of induction of the extraction of empyema through surgical means.

- Due to his study of the human skull and the variations in its features he is said to have been responsible for the launch of the study of physical anthropology.

- Vesalius always encouraged his students to check their findings, and even his own findings, so that they could better understand the structure of the human body.

- In addition to his continual efforts to study anatomy he also worked on medicinal remedies and came to such conclusions as treating syphilis with chinaroot.

- Vesalius claimed that medicine had three aspects: drugs, diet, and 'the use of hands'—mainly suggesting surgery and the knowledge of anatomy and physiology gained through dissection.

- Vesalius was a supporter of 'parallel dissections' in which an animal cadaver and a human cadaver are dissected simultaneously in order to demonstrate the anatomical differences and thus correct Galenic errors.

Scientific and historical impact

[edit]The influence of Vesalius' plates representing the partial dissections of the human figure posing in a landscape setting is apparent in the anatomical plates prepared by the Baroque painter Pietro da Cortona (1596–1669), who executed anatomical plates with figures in dramatic poses, most of them with architectural or landscape backdrops.[25]

In 1844, botanists Martin Martens and Henri Guillaume Galeotti published Vesalea, which is a plant genus in the honeysuckle family Caprifoliaceae and it was named in Vesalius's honour.[26]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ It was a common practice among European scholars in his time to latinize their names. His name is also given as Andrea Vesalius, André Vésale, Andrea Vesalio, Andreas Vesal, Andrés Vesalio and Andre Vesale.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Andreas Vesalius of Brussels, 1514–1564 / [Charles Donald O'Malley]. University of California Press. 1964. p. 47. OCLC 429258. Archived from the original on 23 February 2022. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ "Vesalius | Dictionary.com". www.dictionary.com. Archived from the original on 23 February 2022. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

- ^ O'Malley, Charles Donald (1964). Andreas Vesalius of Brussels, 1514–1564. Berkeley : University of California Press. pp. 21–27.

- ^ a b Gumpert, Martin (1948). "Vesalius". Scientific American. 178 (5): 24–31. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0548-24. ISSN 0036-8733. JSTOR 24945814.

- ^ McRae, Charles (1890). Fathers of biology. London: Percival & Co.

- ^ "Andreas Vesalius and the Challenge to Galen | St John's College, University of Cambridge". www.joh.cam.ac.uk. Retrieved 7 January 2023.

- ^ "Vesalius at 500". The Physician's Palette. Archived from the original on 10 December 2014.

- ^ a b Gumpert, Martin (1948). "Vesalius: Discoverer of the Human Body". Scientific American. 178 (5): 24–31. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0548-24. JSTOR 24945814.

- ^ a b "Comparative Anatomy: Andreas Vesalius – Understanding Evolution". 27 April 2021. Retrieved 7 January 2023.

- ^ O'Malley, Charles Donald (1964). Andreas Vesalius of Brussels, 1514–1564. Berkeley : University of California Press.

- ^ a b "Andreas Vesalius (1514–1564)". BBC History. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

- ^ Bonnier Corporation (May 1872). "Popular Science". The Popular Science Monthly. Bonnier Corporation: 95–100. ISSN 0161-7370.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 10 October 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ a b Harcourt, Glenn (1 January 1987). "Andreas Vesalius and the Anatomy of Antique Sculpture". Representations. 17 (17): 28–61. doi:10.2307/3043792. ISSN 0734-6018. JSTOR 3043792. PMID 11618035.

- ^ O'Malley, Charles Donald (1964). Andreas Vesalius of Brussels, 1514–1564. Berkeley : University of California Press. pp. 203, 314.

- ^ Montagu, M. F. Ashley (1955). "Vesalius and the Galenists". The Scientific Monthly. 80 (4): 230–239. Bibcode:1955SciMo..80..230M. ISSN 0096-3771. JSTOR 20970.

- ^ a b Lambert Teuwissen (31 December 2014). "Vesalius was belangrijker dan Copernicus" (in Dutch). Nederlandse Publieke Omroep. Retrieved 5 February 2015.

- ^ O'Malley, Charles Donald (1964). Andreas Vesalius of Brussels, 1514–1564. Berkeley : University of California Press. p. 311.

- ^ See C.D. O'Malley Andreas Vesalius' Pilgrimage, Isis 45:2, 1954

- ^ O'Malley, C. Donald (1954). Andreas Vesalius' Pilgrimage. Vol. 45/2. pp. 138–144.

{{cite book}}:|magazine=ignored (help) - ^ Kusukawa, Sachiko. "De humani corporis fabrica. Epitome". Cambridge Digital Library. Retrieved 3 July 2014.

- ^ Vallejo-Manzur F. et al. (2003) "The resuscitation greats. Andreas Vesalius, the concept of an artificial airway." "Resuscitation" 56:3–7

- ^ Andreas Vesalius, De humani corporis fabrica (1544), Book II, Ch. 24, 268. Trans. William Frank Rich son, On the Fabric of the Human Body (1999), Book II, 234. As quoted by W. F. Bynum & Roy Porter (2005), Oxford Dictionary of Scientific Quotations: Andreas Vesalius, 595:2, ISBN 0-19-858409-1.

- ^ Michael Servetus Research Archived 13 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine Website with graphical study on the Manuscript of Paris by Servetus

- ^ The Anatomical Plates of Pietro da Cortona, Dover, New York, 1986. They were published in the 18th century. Twenty of the drawings for these plates are now in the Hunterian Library, Glasgow.

- ^ Burkhardt, Lotte (2022). Eine Enzyklopädie zu eponymischen Pflanzennamen [Encyclopedia of eponymic plant names] (pdf) (in German). Berlin: Botanic Garden and Botanical Museum, Freie Universität Berlin. doi:10.3372/epolist2022. ISBN 978-3-946292-41-8. S2CID 246307410. Retrieved 27 January 2022.

Sources

[edit]- Dear, Peter. Revolutionizing the Sciences: European Knowledge and Its Ambitions, 1500–1700. Princeton: Princeton UP, 2001.

- Debus, Allen, ed. Vesalius. Who's Who in the World of Science: From Antiquity to Present. 1st ed. Hanibal: Western Co., 1968.

- O'Malley, Charles Donald (1964). Andreas Vesalius of Brussels 1514–1564. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520310230.

- Porter, Roy, ed. Vesalius. The Biographical Dictionary of Scientists. 2nd Ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 1994.

- Saunders, JB de CM and O'Malley, Charles D. The Illustrations from the Works of Andreas Vesalius of Brussels. New York: Dover, 1973 [reprint].

- "Vesalius." Encyclopedia Americana. 1992.

- Vesalius, Andreas. On the Fabric of the Human Body, translated by W. F. Richardson and J. B. Carman. 5 vols. San Francisco and Novato: Norman Publishing, 1998–2009. The Fabric of the human Body, Translated by Daniel H. Garrison and Malcolm H. Hast. Basel: Karger Publishing, 2013. Garrison, Daniel H. Vesalius: The China Root Epistle. A New Translation and Critical Edition. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

- Williams, Trevor, ed. Vesalius. A Biographical Dictionary of Scientists. 3rd Ed. New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1982.

External links

[edit]- Andreae Vesalii Bruxellensis, Dе humani corporis fabrica libri septem, Basileae 1543

- Anatomia 1522–1867: Anatomical Plates from the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library

- Bibliography van Andreas Vesalius

- Vesalius's « Anatomies » Introduction by Jacqueline Vons

- Places and memories related to Andreas Vesalius

- Play on Vesalius

- Translating Vesalius

- Ars Anatomica collection at University of Edinburgh image service (includes Vesalius's De Humanis Corporis Fabrica)

- Turning the Pages: a virtual copy of Vesalius's De Humanis Corporis Fabrica. From the U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- De humani corporis fabrica. Epitome coloured and complete with manekin at Cambridge Digital Library

- Texts digitized by the Bibliothèque interuniversitaire de santé; see its digital library Medic@.

- Vesalius four centuries later by John F. Fulton. Logan Clendening lecture on the history and philosophy of medicine, University of Kansas, 1950. Full-text PDF.

- Andreas Vesalius, VESALIUS project Archived 18 February 2013 at archive.today. Information about the new DVD "De Humani Corporis Fabrica" produced by Health Science Library of the St. Anna Hospital in Ferrara – Italy.

- Vesalius College in Brussels Archived 9 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- TV report on 500th birthday Vesalius by tvbrussel

- De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem (1543) – full digital facsimile at Linda Hall Library

- Vesalius at 500 – digital exhibition from the University of Missouri Libraries

- Andreas Vesalius at the Mathematics Genealogy Project