Onomatopoeia

Onomatopoeia (or rarely echoism)[1] is a type of word, or the process of creating a word, that phonetically imitates, resembles, or suggests the sound that it describes. Common onomatopoeias in English include animal noises such as oink, meow, roar, and chirp. Onomatopoeia can differ by language: it conforms to some extent to the broader linguistic system.[2][3] Hence, the sound of a clock may be expressed variously across languages: as tick tock in English, tic tac in Spanish and Italian (see photo), dī dā in Mandarin, kachi kachi in Japanese, or ṭik-ṭik in Hindi, Urdu and Bengali.

Etymology and terminology

The word onomatopoeia, with rarer spelling variants like onomatopeia and onomatopœia, is an English word from the Ancient Greek compound ὀνοματοποιία, onomatopoiía, meaning 'name-making', composed of ὄνομα, ónoma, meaning "name";[4] and ποιέω, poiéō, meaning "making".[5][6] It is pronounced /ˌɒnəmætəˈpiːə, -mɑːt-/ ⓘ.[7][8] Words that imitate sounds can thus be said to be onomatopoeic, onomatopoetic,[9] imitative,[10] or echoic.

Uses

In the case of a frog croaking, the spelling may vary because different frog species around the world make different sounds: Ancient Greek brekekekex koax koax (only in Aristophanes' comic play The Frogs) probably for marsh frogs; English ribbit for species of frog found in North America; English verb croak for the common frog.[11]

Some other very common English-language examples are hiccup, zoom, bang, beep, moo, and splash. Machines and their sounds are also often described with onomatopoeia: honk or beep-beep for the horn of an automobile, and vroom or brum for the internal combustion engine. In speaking of a mishap involving an audible arcing of electricity, the word zap is often used (and its use has been extended to describe non-auditory effects of interference).

Human sounds sometimes provide instances of onomatopoeia, as when mwah is used to represent a kiss.[12]

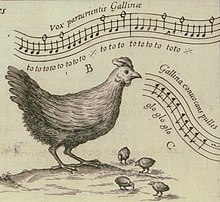

For animal sounds, words like quack (duck), moo (cow), bark or woof (dog), roar (lion), meow/miaow or purr (cat), cluck (chicken) and baa (sheep) are typically used in English (both as nouns and as verbs).

Some languages flexibly integrate onomatopoeic words into their structure. This may evolve into a new word, up to the point that the process is no longer recognized as onomatopoeia. One example is the English word bleat for sheep noise: in medieval times it was pronounced approximately as blairt (but without an R-component), or blet with the vowel drawled, which more closely resembles a sheep noise than the modern pronunciation.

An example of the opposite case is cuckoo, which, due to continuous familiarity with the bird noise down the centuries, has kept approximately the same pronunciation as in Anglo-Saxon times and its vowels have not changed as they have in the word furrow.

Verba dicendi ('words of saying') are a method of integrating onomatopoeic words and ideophones into grammar.

Sometimes, things are named from the sounds they make. In English, for example, there is the universal fastener which is named for the sound it makes: the zip (in the UK) or zipper (in the U.S.) Many birds are named after their calls, such as the bobwhite quail, the weero, the morepork, the killdeer, chickadees and jays, the cuckoo, the chiffchaff, the whooping crane, the whip-poor-will, and the kookaburra. In Tamil and Malayalam, the word for crow is kākā. This practice is especially common in certain languages such as Māori, and so in names of animals borrowed from these languages.

Cross-cultural differences

Although a particular sound is heard similarly by people of different cultures, it is often expressed through the use of different phonetic strings in different languages. For example, the "snip"of a pair of scissors is cri-cri in Italian,[13] riqui-riqui in Spanish,[13] terre-terre[13] or treque-treque[citation needed] in Portuguese, krits-krits in modern Greek,[13] cëk-cëk in Albanian,[citation needed] and kaṭr-kaṭr in Hindi.[citation needed] Similarly, the "honk" of a car's horn is ba-ba (Han: 叭叭) in Mandarin, tut-tut in French, pu-pu in Japanese, bbang-bbang in Korean, bært-bært in Norwegian, fom-fom in Portuguese and bim-bim in Vietnamese.[citation needed]

Onomatopoeic effect without onomatopoeic words

An onomatopoeic effect can also be produced in a phrase or word string with the help of alliteration and consonance alone, without using any onomatopoeic words. The most famous example is the phrase "furrow followed free" in Samuel Taylor Coleridge's The Rime of the Ancient Mariner. The words "followed" and "free" are not onomatopoeic in themselves, but in conjunction with "furrow" they reproduce the sound of ripples following in the wake of a speeding ship. Similarly, alliteration has been used in the line "as the surf surged up the sun swept shore ..." to recreate the sound of breaking waves in the poem "I, She and the Sea".

Comics and advertising

Comic strips and comic books make extensive use of onomatopoeia, often being visually integrated into the images, so that the drawing style emphasizes the sound. Popular culture historian Tim DeForest noted the impact of writer-artist Roy Crane (1901–1977), the creator of Captain Easy and Buz Sawyer:

- It was Crane who pioneered the use of onomatopoeic sound effects in comics, adding "bam," "pow" and "wham" to what had previously been an almost entirely visual vocabulary. Crane had fun with this, tossing in an occasional "ker-splash" or "lickety-wop" along with what would become the more standard effects. Words as well as images became vehicles for carrying along his increasingly fast-paced storylines.[14]

In 2002, DC Comics introduced a villain named Onomatopoeia, an athlete, martial artist, and weapons expert, who is known to verbally speak sounds (i.e., to voice onomatopoeic words such as "crash" and "snap" out loud to accompany the applicable event).

Advertising uses onomatopoeia for mnemonic purposes, so that consumers will remember their products, as in Alka-Seltzer's "Plop, plop, fizz, fizz. Oh, what a relief it is!" jingle, recorded in two different versions (big band and rock) by Sammy Davis Jr.

Rice Krispies (known as Rice Bubbles in Australia) make a "snap, crackle, pop" when one pours on milk. During the 1930s, the illustrator Vernon Grant developed Snap, Crackle and Pop as gnome-like mascots for the Kellogg Company.

Sounds appear in road safety advertisements: "clunk click, every trip" (click the seatbelt on after clunking the car door closed; UK campaign) or "click, clack, front and back" (click, clack of connecting the seat belts; AU campaign) or "make it click" (click of the seatbelt; McDonalds campaign) or "click it or ticket" (click of the connecting seat belt, with the implied penalty of a traffic ticket for not using a seat belt; US DOT (Department of Transportation) campaign).

The sound of the container opening and closing gives Tic Tac its name.

Manner imitation

In many of the world's languages, onomatopoeic-like words are used to describe phenomena beyond the purely auditive. Japanese often uses such words to describe feelings or figurative expressions about objects or concepts. For instance, Japanese barabara is used to reflect an object's state of disarray or separation, and shiiin is the onomatopoetic form of absolute silence (used at the time an English speaker might expect to hear the sound of crickets chirping or a pin dropping in a silent room, or someone coughing). In Albanian, tartarec is used to describe someone who is hasty. It is used in English as well with terms like bling, which describes the glinting of light on things like gold, chrome or precious stones. In Japanese, kirakira is used for glittery things.

Examples in media

- James Joyce in Ulysses (1922) coined the onomatopoeic tattarrattat for a knock on the door.[15] It is listed as the longest palindromic word in The Oxford English Dictionary.[16]

- Whaam! (1963) by Roy Lichtenstein is an early example of pop art, featuring a reproduction of comic book art that depicts a fighter aircraft striking another with rockets with dazzling red and yellow explosions.

- In the 1960s TV series Batman, comic book style onomatopoeic words such as wham!, pow!, biff!, crunch! and zounds! appear onscreen during fight scenes.

- Ubisoft's XIII employed the use of comic book onomatopoeic words such as bam!, boom! and noooo! during gameplay for gunshots, explosions and kills, respectively. The comic-book style is apparent throughout the game and is a core theme, and the game is an adaptation of a comic book of the same name.

- The chorus of American popular songwriter John Prine's song "Onomatopoeia" incorporates onomatopoeic words: "Bang! went the pistol", "Crash! went the window", "Ouch! went the son of a gun".

- The marble game KerPlunk has an onomatopoeic word for a title, from the sound of marbles dropping when one too many sticks has been removed.

- The Nickelodeon cartoon's title KaBlam! is implied to be onomatopoeic to a crash.

- Each episode of the TV series Harper's Island is given an onomatopoeic name which imitates the sound made in that episode when a character dies. For example, in the episode titled "Bang" a character is shot and fatally wounded, with the "Bang" mimicking the sound of the gunshot.

- Mad Magazine cartoonist Don Martin, already popular for his exaggerated artwork, often employed creative comic-book style onomatopoeic sound effects in his drawings (for example, thwizzit is the sound of a sheet of paper being yanked from a typewriter). Fans have compiled The Don Martin Dictionary, cataloging each sound and its meaning.

Cross-linguistic examples

In linguistics

A key component of language is its arbitrariness and what a word can represent,[clarification needed] as a word is a sound created by humans with attached meaning to said sound.[17] It is not possible to determine the meaning of a word purely by how it sounds. However, in onomatopoeic words, these sounds are much less arbitrary; they are connected in their imitation of other objects or sounds in nature. Vocal sounds in the imitation of natural sounds does not necessarily gain meaning, but can gain symbolic meaning.[clarification needed][18] An example of this sound symbolism in the English language is the use of words starting with sn-. Some of these words symbolize concepts related to the nose (sneeze, snot, snore). This does not mean that all words with that sound relate to the nose, but at some level we recognize a sort of symbolism associated with the sound itself. Onomatopoeia, while a facet of language, is also in a sense outside of the confines of language.[19]

In linguistics, onomatopoeia is described as the connection, or symbolism, of a sound that is interpreted and reproduced within the context of a language, usually out of mimicry of a sound.[20] It is a figure of speech, in a sense. Considered a vague term on its own, there are a few varying defining factors in classifying onomatopoeia. In one manner, it is defined simply as the imitation of some kind of non-vocal sound using the vocal sounds of a language, like the hum of a bee being imitated with a "buzz" sound. In another sense, it is described as the phenomena of making a new word entirely.

Onomatopoeia works in the sense of symbolizing an idea in a phonological context, not necessarily constituting a direct meaningful word in the process.[21] The symbolic properties of a sound in a word, or a phoneme, is related to a sound in an environment, and are restricted in part by a language's own phonetic inventory, hence why many languages can have distinct onomatopoeia for the same natural sound. Depending on a language's connection to a sound's meaning, that language's onomatopoeia inventory can differ proportionally. For example, a language like English generally holds little symbolic representation when it comes to sounds, which is the reason English tends to have a smaller representation of sound mimicry than a language like Japanese, which overall has a much higher amount of symbolism related to the sounds of the language.

Evolution of language

In ancient Greek philosophy, onomatopoeia was used as evidence for how natural a language was: it was theorized that language itself was derived from natural sounds in the world around us. Symbolism in sounds was seen as deriving from this.[22] Some linguists hold that onomatopoeia may have been the first form of human language.[19]

Role in early language acquisition

When first exposed to sound and communication, humans are biologically inclined to mimic the sounds they hear, whether they are actual pieces of language or other natural sounds.[23] Early on in development, an infant will vary his/her utterances between sounds that are well established within the phonetic range of the language(s) most heavily spoken in their environment, which may be called "tame" onomatopoeia, and the full range of sounds that the vocal tract can produce, or "wild" onomatopoeia.[21] As one begins to acquire one's first language, the proportion of "wild" onomatopoeia reduces in favor of sounds which are congruent with those of the language they are acquiring.

During the native language acquisition period, it has been documented that infants may react strongly to the more wild-speech features to which they are exposed, compared to more tame and familiar speech features. But the results of such tests are inconclusive.

In the context of language acquisition, sound symbolism has been shown to play an important role.[18] The association of foreign words to subjects and how they relate to general objects, such as the association of the words takete and baluma with either a round or angular shape, has been tested to see how languages symbolize sounds.

In other languages

Japanese

The Japanese language has a large inventory of ideophone words that are symbolic sounds. These are used in contexts ranging from day-to-day conversation to serious news.[24] These words fall into four categories:

- Giseigo (擬声語): mimics sounds made by living things including humans. (e.g. wan-wan for a dog's bark)

- Giongo (擬音語): mimics sounds in nature made by inanimate objects. (e.g. zā-zā for heavy rainfall)

- Gitaigo (擬態語): describes states of the non-auditory external world. (e.g. bisho-bisho for being soaking wet)

- Gijōgo (擬情語): describes psychological states or bodily feelings. (e.g. kuta-kuta for being exhausted)

The two former correspond directly to the concept of onomatopoeia, while the two latter are similar to onomatopoeia in that they are intended to represent a concept mimetically and performatively rather than referentially, but different from onomatopoeia in that they aren't just imitative of sounds. For example, shiinto represents something being silent, just as how an anglophone might say "clatter, crash, bang!" to represent something being noisy. That "representative" or "performative" aspect is the similarity to onomatopoeia.

Sometimes Japanese onomatopoeia produces reduplicated words.[22]

Hebrew

As in Japanese, onomatopoeia in Hebrew sometimes produces reduplicated verbs:[25]: 208

Malay

There is a documented correlation within the Malay language of onomatopoeia that begin with the sound bu- and the implication of something that is rounded, as well as with the sound of -lok within a word conveying curvature in such words like lok, kelok and telok ('locomotive', 'cove', and 'curve' respectively).[26]

Arabic

The Qur'an, written in Arabic, documents instances of onomatopoeia.[19] Of about 77,701 words, there are nine words that are onomatopoeic: three are animal sounds (e.g., mooing), two are sounds of nature (e.g., thunder), and four that are human sounds (e.g., whisper or groan).

Albanian

There is wide array of objects and animals in the Albanian language that have been named after the sound they produce. Such onomatopoeic words are shkrepse (matches), named after the distinct sound of friction and ignition of the match head; take-tuke (ashtray) mimicking the sound it makes when placed on a table; shi (rain) resembling the continuous sound of pouring rain; kukumjaçkë (Little owl) after its "cuckoo" hoot; furçë (brush) for its rustling sound; shapka (slippers and flip-flops); pordhë (loud flatulence) and fëndë (silent flatulence).

Hindi-Urdu

In Hindi and Urdu, onomatopoeic words like bak-bak, cūr-cūr are used to indicate silly talk. Other examples of onomatopoeic words being used to represent actions are phaṭāphaṭ (to do something fast), dhak-dhak (to represent fear with the sound of fast beating heart), ṭip-ṭip (to signify a leaky tap) etc. Movement of animals or objects is also sometimes represented with onomatopoeic words like bhin-bhin (for a housefly) and sar-sarāhat (the sound of a cloth being dragged on or off a piece of furniture). khusr-phusr refers to whispering. bhaunk means bark.

See also

Notes

References

Citations

- ^ "Definition of ECHOISM". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved January 9, 2024.

- ^ Onomatopoeia as a Figure and a Linguistic Principle, Hugh Bredin, The Johns Hopkins University, Retrieved November 14, 2013

- ^ Definition of Onomatopoeia, Retrieved November 14, 2013

- ^ ὄνομα, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ^ ποιέω, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ^ ὀνοματοποιία, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ^ Wells, John C. (2008), Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.), Longman, ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0

- ^ Roach, Peter (2011), Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary (18th ed.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-15253-2

- ^ onomatopoeia. 'Merriam-webster. Retrieved 12 December 2021.

- ^ imitative. Merriam-webster. Retrieved 20 May 2024.

- ^ Basic Reading of Sound Words-Onomatopoeia, Yale University, retrieved October 11, 2013

- ^ "English Oxford Living Dictionaries". Archived from the original on December 29, 2016.

- ^ a b c d Anderson, Earl R. (1998). A Grammar of Iconism. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. p. 112. ISBN 9780838637647.

- ^ DeForest, Tim (2004). Storytelling in the Pulps, Comics, and Radio: How Technology Changed Popular Fiction in America. McFarland. ISBN 9780786419029.

- ^ James Joyce (1982). Ulysses. Editions Artisan Devereaux. pp. 434–. ISBN 978-1-936694-38-9.

... I was just beginning to yawn with nerves thinking he was trying to make a fool of me when I knew his tattarrattat at the door he must ...

- ^ O.A. Booty (January 1, 2002). Funny Side of English. Pustak Mahal. pp. 203–. ISBN 978-81-223-0799-3.

The longest palindromic word in English has twelve letters: tattarrattat. This word, appearing in the Oxford English Dictionary, was invented by James Joyce and used in his book Ulysses (1922), and is an imitation of the sound of someone [farting].

- ^ Assaneo, María Florencia; Nichols, Juan Ignacio; Trevisan, Marcos Alberto (January 1, 2011). "The anatomy of onomatopoeia". PLOS ONE. 6 (12): e28317. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...628317A. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0028317. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3237459. PMID 22194825.

- ^ a b RHODES, R (1994). "Aural Images". In J. Ohala, L. Hinton & J. Nichols (Eds.) Sound Symbolism. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ a b c Seyedi, Hosein; Baghoojari, ELham Akhlaghi (May 2013). "The Study of Onomatopoeia in the Muslims' Holy Write: Qur'an" (PDF). Language in India. 13 (5): 16–24.

- ^ Bredin, Hugh (August 1, 1996). "Onomatopoeia as a Figure and a Linguistic Principle". New Literary History. 27 (3): 555–569. doi:10.1353/nlh.1996.0031. ISSN 1080-661X. S2CID 143481219.

- ^ a b Laing, C. E. (September 15, 2014). "A phonological analysis of onomatopoeia in early word production". First Language. 34 (5): 387–405. doi:10.1177/0142723714550110. S2CID 147624168.

- ^ a b Osaka, Naoyuki (1990). "Multidimensional Analysis of Onomatopoeia – A note to make sensory scale from word". Studia phonologica. 24: 25–33. hdl:2433/52479. NAID 120000892973.

- ^ Assaneo, María Florencia; Nichols, Juan Ignacio; Trevisan, Marcos Alberto (December 14, 2011). "The Anatomy of Onomatopoeia". PLOS ONE. 6 (12): e28317. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...628317A. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0028317. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3237459. PMID 22194825.

- ^ Inose, Hiroko. "Translating Japanese Onomatopoeia and Mimetic Words." N.p., n.d. Web.

- ^ a b c Zuckermann, Ghil'ad (2003), Language Contact and Lexical Enrichment in Israeli Hebrew. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9781403917232 / ISBN 9781403938695 [1]

- ^ WILKINSON, R. J. (January 1, 1936). "Onomatopoeia in Malay". Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. 14 (3 (126)): 72–88. JSTOR 41559855.

General references

- Crystal, David (1997). The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Language (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-55967-7.

- Smyth, Herbert Weir (1920). Greek Grammar. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press. p. 680. ISBN 0-674-36250-0.