Environmental vegetarianism

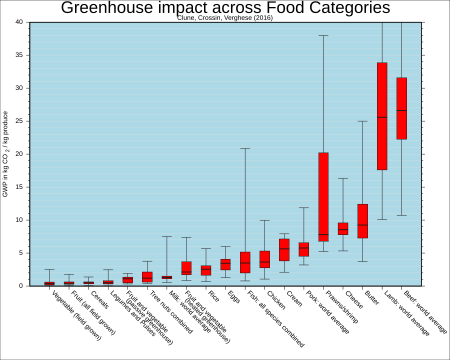

Environmental vegetarianism is the practice of vegetarianism that is motivated by the desire to create a sustainable diet, which avoids the negative environmental impact of meat production. Livestock as a whole is estimated to be responsible for around 15% of global greenhouse gas emissions.[2][a] As a result, significant reduction in meat consumption has been advocated by, among others, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change in their 2019 special report[3] and as part of the 2017 World Scientists' Warning to Humanity.[4][5]

Other than climate change, the livestock industry is the primary driver behind biodiversity loss and deforestation and is significantly relevant to environmental concerns such as water and land use, pollution, and unsustainability.[6][7][8][9]

Environmental impact of animal products

[edit]

Four-fifths of agricultural emissions arise from the livestock sector.[10]

According to the 2006 Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) report Livestock's Long Shadow, animal agriculture contributes on a "massive scale" to global warming, air pollution, land degradation, energy use, deforestation, and biodiversity decline.[11] The FAO report estimates that the livestock (including poultry) sector (which provides draft animal power, leather, wool, milk, eggs, fertilizer, pharmaceuticals, etc., in addition to meat) contributes about 18 percent of global GHG emissions expressed as 100-year CO2 equivalents.[b] This estimate was based on life-cycle analysis, including feed production, land use changes, etc., and used GWP (global warming potential) of 23 for methane and 296 for nitrous oxide, to convert emissions of these gases to 100-year CO2 equivalents. The FAO report concluded that "the livestock sector emerges as one of the top two or three most significant contributors to the most serious environmental problems, at every scale from local to global".[11] The report found that livestock's contribution to greenhouse gas emissions was greater than that of the global transportation sector.

A 2009 study by the Worldwatch Institute argued that the FAO's report had underestimated impacts related to methane, land use and respiration, placing livestock at 51% of total global emissions.[12]

According to a 2002 paper:

The industrial agriculture system consumes fossil fuel, water, and topsoil at unsustainable rates. It contributes to numerous forms of environmental degradation, including air and water pollution, soil depletion, diminishing biodiversity, and fish die-offs. Meat production contributes disproportionately to these problems, in part because feeding grain to livestock to produce meat—instead of feeding it directly to humans—involves a large energy loss, making animal agriculture more resource intensive than other forms of food production. ... One personal act that can have a profound impact on these issues is reducing meat consumption. To produce 1 pound of feedlot beef requires about 2,400 gallons of water and 7 pounds of grain (42). Considering that the average American consumes 97 pounds of beef (and 273 pounds of meat in all) each year, even modest reductions in meat consumption in such a culture would substantially reduce the burden on our natural resources.[13]

The environmental impacts of animal production vary with the method of production, although "[overall] impacts of the lowest-impact animal products typically exceed those of vegetable substitutes".[7]

Average greenhouse gas emissions per diet

[edit]| Diet | Mean dietary emissions

(In kilograms of carbon dioxide equivalents) |

|---|---|

| All meat-eaters | |

| High meat-eaters ( ≥ 100 g/day) | |

| Medium meat-eaters (50–99 g/day) | |

| Low meat-eaters ( < 50 g/day) | |

| Fish-eaters | |

| Vegetarians | |

| Vegans |

Methane

[edit]A 2017 study published in the journal Carbon Balance and Management found animal agriculture's global methane emissions are 11% higher than previous estimates, based on data from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.[15]

Pesticide use

[edit]According to a 2022 report from World Animal Protection and the Center for Biological Diversity around 235 million pounds of pesticides are used for animal feed purposes annually in the United States alone, which threatens thousands of endangered species of plants and animals. Rather than arguing for biological agriculture, the report argues consumers should reduce their consumption of animal products and to transition towards plant-based diets in order to hinder the growth of factory farming and protect endangered species of wildlife.[16]

Land use

[edit]

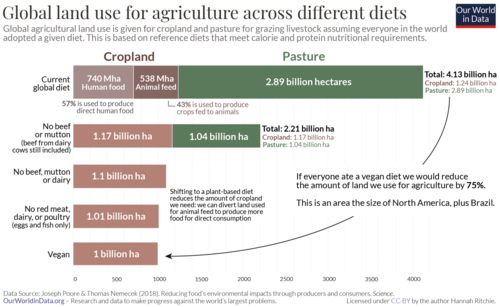

A 2003 paper published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, after calculating effects on energy, land, and water use, concluded that meat-based diets require more resources and are less sustainable than lacto-ovo vegetarian diets.[18] "The water required for a meat-eating diet is twice as much needed for a 2,000-litre-a-day vegetarian diet".[19]

According to Cornell University scientists: "The heavy dependence on fossil energy suggests that the US food system, whether meat-based or plant-based, is not sustainable".[20] However, they also write: "The meat-based food system requires more energy, land, and water resources than the lactoovovegetarian diet. In this limited sense, the lactoovovegetarian diet is more sustainable than the average American meat-based diet."[20] One of these Cornell scientists "depicted grain-fed livestock farming as a costly and nonsustainable way to produce animal protein", but "distinguished grain-fed meat production from pasture-raised livestock, calling cattle-grazing a more reasonable use of marginal land".[21]

The use of ever increasing amounts of land for meat production and livestock rearing instead of plants and grains for human diets is, according to sociologist David Nibert, "a leading cause of malnutrition, hunger, and famine around the world."[22]

Land degradation

[edit]We must change our diet. The planet can't support billions of meat-eaters.

Another agricultural effect is on land degradation. Cattle are a known cause for soil erosion through trampling of the ground and overgrazing.[24] Much of the world's crops are used to feed animals.[25] With 30 percent of the Earth's land devoted to raising livestock,[26] a major cutback is needed to keep up with growing population. Demand for meat is expected to double by 2050;[27] in China, for example, where vegetable-based diets were once the norm, demand for meat will continue to be great in absolute terms, even though demand growth will slow.[28] As countries are developing, incomes are increasing, and consumption of animal products is associated with prosperity. This growing demand is unsustainable.[29]

The ability of soil to absorb water by infiltration is important for minimizing runoff and soil erosion. Researchers in Iowa reported that a soil under perennial pasture grasses grazed by livestock was able to absorb far more water than the same kind of soil under two annual crops: corn and soybeans.[30][31]

Biodiversity loss

[edit]The 2019 IPBES Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services found that the primary driver of biodiversity loss is human land use, which deprives other species of land needed for their survival, with the meat industry playing a significant role in this process. Around 25% of Earth's ice-free land is used for cattle rearing.[34] Other studies have also warned that meat consumption is accelerating mass extinctions globally.[35][36][37] A 2017 study by the World Wildlife Fund attributed 60% of biodiversity loss to the land needed to rear tens of billions of farm animals.[38]

A May 2018 study stated that while wildlife has been decimated since the dawn of human civilization, with wild mammals plummeting by 83%, livestock populations reared by humans for consumption have increased.[39] Livestock make up 60% of the biomass of all mammals on Earth, followed by humans (36%) and wild mammals (4%).[39] As for birds, 70% are domesticated, such as poultry, whereas only 30% are wild.[39][40]

Water

[edit]Animal production has a large impact on water pollution and usage. According to the Water Education Foundation, it takes 2,464 gallons of water to produce one pound of beef in California, whereas it takes only 25 gallons of water to produce one pound of wheat.[41] Raising a large amount of livestock creates a massive amount of manure and urine, which can pollute natural resources by changing the pH of water, contaminates the air, and emits a major amount of gas that directly affects global warming. As most livestock are raised in small confined spaces to cut down on cost, this increases the problem of concentrated waste. Livestock in the United States produces 2.7 trillion pounds of manure each year, which is ten times more than what is produced by the entire U.S. population. There are issues with how animal waste is disposed, as some is used as fertilizer while some farmers create manure lagoons which store millions of gallons of animal waste which is extremely unsafe and detrimental to the environment.[41]

Relation to other arguments

[edit]Massive reductions in meat consumption in industrial nations will ease the health care burden while improving public health; declining livestock herds will take pressure off rangelands and grainlands, allowing the agricultural resource base to rejuvenate. As populations grow, lowering meat consumption worldwide will allow more efficient use of declining per capita land and water resources, while at the same time making grain more affordable to the world's chronically hungry.[42]

Although motivations frequently overlap, environmental vegetarians and vegans can be contrasted with those who are primarily motivated by concerns about animal welfare (one kind of ethical vegetarianism), health, or who avoid meat to save money or out of necessity (economic vegetarianism).[43][44] Some also believe vegetarianism will improve global food security, or curb starvation.

Health

[edit]A study in Climate Change concluded "if ... average diets among UK adults conformed to WHO recommendations, their associated GHG emissions would be reduced by 17%. Further GHG emission reductions of around 40% could be achieved by making realistic modifications to diets so that they contain fewer animal products and processed snacks and more fruit, vegetables and cereals."[45] A study in The Lancet estimated that the "30% reduction in livestock production" by 2030 required to meet the UK Committee on Climate Change's agricultural would also result in a roughly 15% decrease in ischaemic heart disease.[10]

A 2018 report published in PNAS asserted that farmers in the United States could sustain more than twice as many people than they do currently if they abandoned rearing farm animals for human consumption and instead focused on growing plants.[46]

For developed countries, a CAST report estimates an average of 2.6 pounds of grain feed per pound of beef carcass meat produced. For developing countries, the estimate is 0.3 pounds per pound. (Some very dissimilar figures are sometimes seen; the CAST report discusses common sources of error and discrepancies among such figures.)[47] In 2007, US per capita beef consumption was 62.2 pounds per year, and US per capita meat (red meat plus fish plus poultry) consumption totaled 200.7 pounds (boneless trimmed weight basis).[48]

Support

[edit]

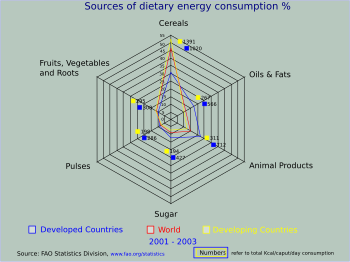

Globalization and modernization has resulted in Western consumer cultures spreading to countries like China and India, including meat-intensive diets which are supplanting traditional plant-based diets. Around 166 to more than 200 billion land and aquatic animals are consumed by a global population of over 7 billion annually, which philosopher and animal rights activist Steven Best argues is "completely unsustainable".[50][51] A 2018 study published in Science states that meat consumption is set to increase by some 76% by 2050 as the result of human population growth and rising affluence, which will increase greenhouse gas emissions and further reduce biodiversity.[52][53]

A 2018 report in Nature found that a significant reduction in meat consumption is necessary to mitigate climate change, especially as the population rises to a projected 10 billion in the coming decades.[54] According to a 2019 report in The Lancet, global meat consumption needs to be reduced by 50 percent to mitigate for climate change.[55]

In November 2017, 15,364 world scientists signed a Warning to Humanity calling for, among other things, drastically diminishing our per capita consumption of meat.[56]

A 2010 report from the United Nations Environment Programme's (UNEP) International Panel of Sustainable Resource Management stated:

Impacts from agriculture are expected to increase substantially due to population growth and increasing consumption of animal products. Unlike fossil fuels, it is difficult to look for alternatives: people have to eat. A substantial reduction of impacts would only be possible with a substantial worldwide diet change, away from animal products.[25][57]

The aforementioned Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services also suggested that a reduction in meat consumption would be required to help preserve biodiversity.[34]

A 2010 UN report, Assessing the Environmental Impacts of Consumption and Production, argued that animal products "in general require more resources and cause higher emissions than plant-based alternatives".[58]: 80 It proposed a move away from animal products to reduce environmental damage.[c][59]

A 2015 study determined that significant biodiversity loss can be attributed to the growing demand for meat, a significant driver of deforestation and habitat destruction, with species-rich habitats converted to agriculture for livestock production.[61][62][63] A 2017 World Wildlife Fund study found that 60% of biodiversity loss can be attributed to the vast scale of feed crop cultivation needed to rear tens of billions of farm animals, which puts enormous strain on natural resources, resulting in extensive loss of lands and species.[64] In 2017, 15,364 world scientists signed a warning to humanity calling for, among other things, "promoting dietary shifts towards mostly plant-based foods".[65]

According to a July 2019 report by the World Resources Institute the global population will increase to roughly 10 billion by the middle of the century, with demand for ruminant meat rising by 88%. The report posits that Americans and Europeans will need to reduce their beef consumption by 40% and 22% respectively in order to feed so many people and at the same time avert an ecological catastrophe.[66]

In November 2019, a warning on the "climate emergency" from over 11,000 scientists from over 100 countries said that "eating mostly plant-based foods while reducing the global consumption of animal products, especially ruminant livestock, can improve human health and significantly lower GHG emissions (including methane in the “Short-lived pollutants” step)." The warning also says it this will "free up croplands for growing much-needed human plant food instead of livestock feed, while releasing some grazing land to support natural climate solutions."[67][68]

A 2020 study by researchers from the University of Michigan and Tulane University, which was commissioned by the Center for Biological Diversity, asserts that if the U.S. cut its meat consumption by half, it could result in diet-related GHG emissions being reduced by 35%, a decline of 1.6 billion tons.[69]

A 2019 correction to a major 2018 study in Science of food's impact on the environment found that, after the negative emissions of land use change were accounted for, eliminating animal products from the food system would reduce total global greenhouse gas emissions from all sectors by 28%.[7][70]

A 2018 study found that global adoption of plant-based diets would reduce agricultural land use by 76% (3.1 billion hectares, an area the size of Africa) and cut total global greenhouse gas emissions by 28%. Half of this emissions reduction came from avoided emissions from animal production including methane and nitrous oxide, and half from trees re-growing on abandoned farmlands that remove carbon dioxide from the air.[71][72] The authors conclude that avoiding meat and dairy is the "single biggest way" to reduce one's impact on Earth.[73]

The 2019 IPBES Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services found that industrial agriculture and overfishing are the primary drivers of the extinction crisis, with the meat and dairy industries having a substantial impact.[74][75] On 8 August 2019, the IPCC released a summary of the 2019 special report which asserted that a shift towards plant-based diets would help to mitigate and adapt to climate change.[76]

A 2022 study found that for high-income nations alone 100 billion tons of carbon dioxide could be removed from the air by the end of the century through a shift to plant-based diets and re-wilding of farmlands. The researchers coined the term double climate dividend to describe the effect that re-wilding after a diet shift can have.[77][78] But they note: "We don't have to be purist about this, even just cutting animal intake would be helpful. If half of the public in richer regions cut half the animal products in their diets, you're still talking about a massive opportunity in environmental outcomes and public health".[79]

A 2023 study published in Nature Food found that a vegan diet vastly decreases the impact on the environment from food production, such as reducing emissions, water pollution and land use by 75%, reducing the destruction of wildlife by 66% and the usage of water by 54%.[80]

Criticism

[edit]Bill Mollison has argued in his Permaculture Design Course that vegetarianism exacerbates soil erosion. This is because removing a plant from a field removes all the nutrients it obtained from the soil while removing an animal leaves the field intact. On US farmland, much less soil erosion is associated with pastureland used for livestock grazing than with land used for the production of crops.[81] However, as mentioned above, all dietary change scenarios that assume decreased meat consumption are strictly less land-demanding. Robert Hart has also developed forest gardening, which has since been adopted as a common permaculture design element, as a sustainable plant-based food production system.[82] A balanced diet based on the food pyramid would present as an alternative to vegetarianism.

In 2015, researches from Carnegie Mellon University claimed that environmental vegetarianism appears more harmful than helpful to our environment. Environmental vegetarianism actually takes more environmental costs, environmentally and financially, which backfires. Paul Fischbeck, Michelle Tom, and Chris Hendrickson, researchers in civil and environmental engineering at Carnegie Mellon University, investigated the impact of America's obesity crisis on the environment by analyzing the food supply chain's resource usage. The study offers a nuanced exploration into the environmental impact of dietary choices, specifically contrasting the perceived benefits of vegetarian and USDA-recommended "healthier" diets against their ecological footprints. The research underscores that while reducing overall calorie intake can decrease the environmental burden by around 9%, opting for diets heavy in fruits, vegetables, dairy, and seafood significantly increases resource demands—leading to a 38% rise in energy consumption, a 10% increase in water use, and a 6% uptick in greenhouse gas emissions.[83] This counterintuitive result pivots on the intensive resources required to produce these "healthier" food options, challenging simplified narratives around diet and sustainability and pointing to the need for a comprehensive understanding of food's environmental costs.

In 2017, a study in PNAS claimed that U.S. GHG emissions would only decrease 2.6% (or 28% of agricultural GHG emissions) if animals were completely removed from U.S. agriculture.[84] However, the study's underlying assumptions were heavily criticized.[85][86][87] The authors defended their work in a follow-up 2018 letter.[88] Furthermore, the animals removed from agriculture would remain alive and emitting GHG.

In 2019, Loma Linda University School of Public Health published a research article which outlined that while, generally, vegetarian diet is more environmentally sustainable than omnivorous diet, its environmental benefits heavily depend on the specific foods included in the diet.[89] This way, if beef is replaced by a larger quantity of dairy, the environmental benefit of such a switch may be close to zero.[90] Similarly, if the vegetarian diet includes out-of-season fruits or vegetables cultivated in high-energy-consumption greenhouses, the GHG emissions offset could ultimately be reversed. [91]

Evidence suggests that intensive livestock farming is a poor solution to world hunger, given its impact on personal health and the environment, but intensive industrialised farming of soya, maize and grains comes at a significant carbon cost, too – as does flying in the ingredients to keep berries and nut butters on acai bowls or avocado on toast.[92]

See also

[edit]- Animal–industrial complex

- Cowspiracy

- Cultured meat

- Demitarian

- Devour the Earth

- Diet for a New America

- Entomophagy (another environmental approach for obtaining food)

- Environmentalism

- Environmental pescetarianism

- Environmental veganism

- Ethics of vegetarianism

- Low-carbon diet

- In vitro meat

- Regenerative agriculture

- Stock-free agriculture

- Sustainable diet

- Vegan organic gardening

Notes

[edit]- ^ This is in line with the FAO's earlier estimate of 18%, published in Livestock's Long Shadow in 2006. They caution that "the two figures cannot be accurately compared, as reference periods and sources differ."

- ^ This is in line with the FAO's more recent figure of 14.5 percent. They caution that "the two figures cannot be accurately compared, as reference periods and sources differ."[2]

- ^ United Nations Environment Programme (2010): "Impacts from agriculture are expected to increase substantially due to population growth, increasing consumption of animal products. Unlike fossil fuels, it is difficult to look for alternatives: people have to eat. A substantial reduction of impacts would only be possible with a substantial worldwide diet change, away from animal products."[58]: 82

References

[edit]- ^ Stephen Clune; Enda Crossin; Karli Verghese (1 January 2017). "Systematic review of greenhouse gas emissions for different fresh food categories" (PDF). Journal of Cleaner Production. 140 (2): 766–783. Bibcode:2017JCPro.140..766C. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.04.082.

- ^ a b "Key facts and findings". Food and Agriculture Organization. Archived from the original on 4 June 2021. Retrieved 29 April 2019.

- ^ Schiermeier, Quirin (8 August 2019). "Eat less meat: UN climate change report calls for change to human diet". Nature. Retrieved 10 August 2019.

- ^ "Climate change food calculator: What's your diet's carbon footprint?". 13 December 2018. Retrieved 30 April 2019.

- ^ Ripple WJ, Wolf C, Newsome TM, Galetti M, Alamgir M, Crist E, Mahmoud MI, Laurance WF (13 November 2017). "World Scientists' Warning to Humanity: A Second Notice". BioScience. 67 (12): 1026–1028. doi:10.1093/biosci/bix125. hdl:11336/71342.

- ^ Carrington, Damian (3 February 2021). "Plant-based diets crucial to saving global wildlife, says report". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ^ a b c Nemecek, T.; Poore, J. (2018). "Reducing food's environmental impacts through producers and consumers". Science. 360 (6392): 987–992. Bibcode:2018Sci...360..987P. doi:10.1126/science.aaq0216. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 29853680.

- ^ Bittman, Mark (27 January 2008). "Rethinking the Meat-Guzzler". The New York Times. Retrieved 8 November 2017 – via www.nytimes.com.

- ^ Carrington, Damian (10 October 2018). "Huge reduction in meat-eating 'essential' to avoid climate breakdown". The Guardian. Retrieved 30 April 2019.

- ^ a b Friel, Sharon (2009). "Public health benefits of strategies to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions: food and agriculture". The Lancet. 374 (9706): 2016–2025. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61753-0. PMID 19942280. S2CID 6318195.

- ^ a b Steinfeld, Henning; Gerber, Pierre; Wassenaar, Tom; Castel, Vincent; Rosales, Mauricio; de Haan, Cees (2006), Livestock's Long Shadow: Environmental Issues and Options (PDF), Rome: FAO

- ^ "Study claims meat creates half of all greenhouse gases". Independent.co.uk. 1 November 2009.

- ^ Horrigan, Leo; Lawrence, Robert S; Walker, Polly (May 2002). "How Sustainable Agriculture Can Address the Environmental and Human Health Harms of Industrial Agriculture". Environmental Health Perspectives. 110 (5): 445–456. Bibcode:2002EnvHP.110..445H. doi:10.1289/ehp.02110445. PMC 1240832. PMID 12003747.

- ^ Scarborough, Peter; Appleby, Paul N.; Mizdrak, Anja; Briggs, Adam D. M.; Travis, Ruth C.; Bradbury, Kathryn E.; Key, Timothy J. (2014). "Dietary greenhouse gas emissions of meat-eaters, fish-eaters, vegetarians and vegans in the UK". Climatic Change. 125 (2): 179–192. Bibcode:2014ClCh..125..179S. doi:10.1007/s10584-014-1169-1. ISSN 0165-0009. PMC 4372775. PMID 25834298.

- ^ Wolf, Julie; Asrar, Ghassem R.; West, Tristram O. (29 September 2017). "Revised methane emissions factors and spatially distributed annual carbon fluxes for global livestock". Carbon Balance and Management. 12 (16): 16. Bibcode:2017CarBM..12...16W. doi:10.1186/s13021-017-0084-y. PMC 5620025. PMID 28959823.

- ^ Boyle, Louise (22 February 2022). "US meat industry using 235m pounds of pesticides a year, threatening thousands of at-risk species, study finds". The Independent. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- ^ Carrington, Damian (31 May 2018). "Avoiding meat and dairy is 'single biggest way' to reduce your impact on Earth". The Guardian. Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- ^ Pimentel, David; Pimentel, Marcia (1 September 2003). "Sustainability of meat-based and plant-based diets and the environment". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 78 (3): 660S – 663S. doi:10.1093/ajcn/78.3.660s. PMID 12936963.

- ^ "Solution for the world's water woes: Rising populations and growing demand is making the world a thirsty planet; the solution lies in people reducing the size of their "water footprints" - Water Education Foundation". www.watereducation.org. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- ^ a b Pimentel, David; Pimentel, Marcia (September 2003). "Sustainability of meat-based and plant-based diets and the environment". American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 78 (3): 660S – 663S. doi:10.1093/ajcn/78.3.660S. PMID 12936963.

- ^ "U.S. could feed 800 million people with grain that livestock eat, Cornell ecologist advises animal scientists". Cornell Chronicle. 7 August 1997. Retrieved 19 July 2015.

- ^ Nibert, David (2011). "Origins and Consequences of the Animal Industrial Complex". In Steven Best; Richard Kahn; Anthony J. Nocella II; Peter McLaren (eds.). The Global Industrial Complex: Systems of Domination. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 204. ISBN 978-0739136980.

- ^ Dalton, Jane (26 August 2020). "Go vegetarian to save wildlife and the planet, Sir David Attenborough urges". The Independent. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- ^ C.Michael Hogan. 2009. Overgrazing. Encyclopedia of Earth. Sidney Draggan, topic ed.; Cutler J. Cleveland, ed., National council for Science and the Environment, Washington DC

- ^ a b Carus, Felicity (2 June 2010). "UN urges global move to meat and dairy-free diet". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 October 2011.

- ^ "Livestock Grazing- Combats or Spreads Desertification?". Archived from the original on 1 July 2007.

- ^ "Meat production continues to rise". Worldwatch Institute. 18 October 2018. Archived from the original on 7 September 2022. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

- ^ "Rabobank: China's Animal Protein Outlook to 2020: Growth in Demand, Supply and Trade". Rabobank. 2 March 2017. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

- ^ "Sustainability Pathways: Sustainability and livestock". www.fao.org. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- ^ Bharati et al. 2002. Agroforestry Systems 56: 249-257

- ^ "Tobacco | Land & Water | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations | Land & Water | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations". www.fao.org. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- ^ Damian Carrington, "Humans just 0.01% of all life but have destroyed 83% of wild mammals – study", The Guardian, 21 May 2018 (page visited on 19 August 2018).

- ^ Baillie, Jonathan; Zhang, Ya-Ping (2018). "Space for nature". Science. 361 (6407): 1051. Bibcode:2018Sci...361.1051B. doi:10.1126/science.aau1397. PMID 30213888.

- ^ a b Watts, Jonathan (6 May 2019). "Human society under urgent threat from loss of Earth's natural life". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- ^ Morell, Virginia (11 August 2015). "Meat-eaters may speed worldwide species extinction, study warns". Science. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- ^ Machovina, B.; Feeley, K. J.; Ripple, W. J. (2015). "Biodiversity conservation: The key is reducing meat consumption". Science of the Total Environment. 536: 419–431. Bibcode:2015ScTEn.536..419M. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.07.022. PMID 26231772.

- ^ Woodyatt, Amy (26 May 2020). "Human activity threatens billions of years of evolutionary history, researchers warn". CNN. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

Research showed that among the biggest threats to threatened species was eating meat, Gumbs said.

- ^ Smithers, Rebecca (5 October 2017). "Vast animal-feed crops to satisfy our meat needs are destroying planet". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- ^ a b c Bar-On, Yinon M; Phillips, Rob; Milo, Ron (2018). "The biomass distribution on Earth". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 115 (25): 6506–6511. Bibcode:2018PNAS..115.6506B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1711842115. PMC 6016768. PMID 29784790.

- ^ Carrington, Damian (21 May 2018). "Humans just 0.01% of all life but have destroyed 83% of wild mammals – study". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- ^ a b admin (4 April 2007). "The Environmental Impact of a Meat-Based Diet". Vegetarian Times. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- ^ United States Leads World Meat Stampede | Worldwatch Institute Archived May 17, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Nuwer, Rachel. "What would happen if the world suddenly went vegetarian?". www.bbc.com. BBC. Retrieved 30 April 2019.

- ^ Katherine Manning. "Eat Better and Improve Your Health For Less Money". Archived from the original on 14 November 2012. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ^ Green, Rosemary (2015). "The potential to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in the UK through healthy and realistic dietary change". Climatic Change. 129 (1–2): 253–265. Bibcode:2015ClCh..129..253G. doi:10.1007/s10584-015-1329-y. hdl:10.1007/s10584-015-1329-y. S2CID 154322542.

- ^ Kaplan, Karen (26 March 2018). "By going vegan, America could feed an additional 390 million people, study suggests". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 30 March 2018. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

If U.S. farmers took all the land currently devoted to raising cattle, pigs and chickens and used it to grow plants instead, they could sustain more than twice as many people as they do now, according to a report published Monday in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

- ^ Bradford, E. et al. 1999. Animal Agriculture and Global Food Supply. Council on Agricultural Science and Technology. 92 pp.

- ^ USDA. 2010. Agricultural Statistics 2010, Table 13-7

- ^ "FAOSTAT" (PDF). faostat.fao.org.

- ^ Best, Steven (2014). "Rethinking Revolution: Veganism, Animal Liberation, Ecology, and the Left". The Politics of Total Liberation: Revolution for the 21st Century. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 97. doi:10.1057/9781137440723_4. ISBN 978-1137471116.

- ^ Benatar, David (2015). "The Misanthropic Argument for Anti-natalism". In S. Hannan; S. Brennan; R. Vernon (eds.). Permissible Progeny?: The Morality of Procreation and Parenting. Oxford University Press. p. 44. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199378111.003.0002. ISBN 978-0199378128.

- ^ Devlin, Hannah (19 July 2018). "Rising global meat consumption 'will devastate environment'". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

- ^ Godfray, H. Charles J.; Aveyard, Paul; et al. (2018). "Meat consumption, health, and the environment". Science. 361 (6399). Bibcode:2018Sci...361M5324G. doi:10.1126/science.aam5324. PMID 30026199. S2CID 49895246.

- ^ Achenbach, Joel (10 October 2018). "Earth's population is skyrocketing. How do you feed 10 billion people sustainably?". The Washington Post. Retrieved 16 October 2018.

- ^ Gibbens, Sarah (16 January 2019). "Eating meat has 'dire' consequences for the planet, says report". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 17 January 2019. Retrieved 21 January 2019.

- ^ Ripple WJ, Wolf C, Newsome TM, Galetti M, Alamgir M, Crist E, Mahmoud MI, Laurance WF (13 November 2017). "World Scientists' Warning to Humanity: A Second Notice". BioScience. 67 (12): 1026–1028. doi:10.1093/biosci/bix125. hdl:11336/71342.

- ^ Assessing the Environmental Impacts of Consumption and Production: Priority Products and Materials (PDF), UNEP, 2010, p. 82, archived from the original (PDF) on 16 June 2012, retrieved 17 July 2015

- ^ a b Assessing the Environmental Impacts of Consumption and Production, International Panel for Resource Management, United Nations Environment Programme, June 2010.

- ^ Carus, Felicity (2 June 2010). "UN urges global move to meat and dairy-free diet". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 3 March 2018. Retrieved 3 March 2018."Energy and Agriculture Top Resource Panel's Priority List for Sustainable 21st Century" Archived 19 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine, United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), Brussels, 2 June 2010.For an opposing position, Simon Fairlie, Meat: A Benign Extravagance, Chelsea Green Publishing, 2010.

- ^ Scarborough, Peter; Appleby, Paul N.; Mizdrak, Anja; Briggs, Adam D. M.; Travis, Ruth C.; Bradbury, Kathryn E.; Key, Timothy J. (11 June 2014). "Dietary greenhouse gas emissions of meat-eaters, fish-eaters, vegetarians and vegans in the UK". Climatic Change. 125 (2): 179–192. Bibcode:2014ClCh..125..179S. doi:10.1007/s10584-014-1169-1. PMC 4372775. PMID 25834298.

- ^ Machovina, Brian; Feeley, Kenneth J.; Ripple, William J. (December 2015). "Biodiversity conservation: The key is reducing meat consumption". Science of the Total Environment. 536: 419–431. Bibcode:2015ScTEn.536..419M. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.07.022. PMID 26231772.

- ^ Morell, Virginia (11 August 2015). "Meat-eaters may speed worldwide species extinction, study warns". Science. doi:10.1126/science.aad1607.

- ^ Woodyatt, Amy (26 May 2020). "Human activity threatens billions of years of evolutionary history, researchers warn". CNN. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

Research showed that among the biggest threats to threatened species was eating meat, Gumbs said.

- ^ Smithers, Rebecca (5 October 2017). "Vast animal-feed crops to satisfy our meat needs are destroying planet". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 3 March 2018. Retrieved 3 March 2018.

- ^ Ripple, William J.; Wolf, Christopher; Newsome, Thomas M.; Galetti, Mauro; Alamgir, Mohammed; Crist, Eileen; Mahmoud, Mahmoud I.; Laurance, William F. (December 2017). "World Scientists' Warning to Humanity: A Second Notice". BioScience. 67 (12): 1026–1028. doi:10.1093/biosci/bix125. hdl:11336/71342.

- ^ Christensen, Jen (17 July 2019). "To help save the planet, cut back to a hamburger and a half per week". CNN. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- ^ Ripple, William J.; Wolf, Christopher; Newsome, Thomas M; Barnard, Phoebe; Moomaw, William R (5 November 2019). "World Scientists' Warning of a Climate Emergency". BioScience. doi:10.1093/biosci/biz088. hdl:1808/30278. Retrieved 8 November 2019.

- ^ Carrington, Damian (5 November 2019). "Climate crisis: 11,000 scientists warn of 'untold suffering'". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 November 2019.

- ^ Germanos, Andrea (30 April 2020). "Slashing US Meat Consumption by Half Could Cut Diet-Related Greenhouse Gas Emissions by 35%: Study". Common Dreams. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- ^ Poore, J.; Nemecek, T. (22 February 2019). "Erratum for the Research Article "Reducing food's environmental impacts through producers and consumers" by J. Poore and T. Nemecek". Science. 363 (6429). doi:10.1126/science.aaw9908. PMID 30792276.

- ^ Poore, J.; Nemecek, T. (1 June 2018). "Reducing food's environmental impacts through producers and consumers". Science. 360 (6392): 987–992. Bibcode:2018Sci...360..987P. doi:10.1126/science.aaq0216. PMID 29853680.

- ^ Carrington, Damian (31 May 2018). "Avoiding meat and dairy is 'single biggest way' to reduce your impact on Earth". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 March 2019.

A vegan diet is probably the single biggest way to reduce your impact on planet Earth, not just greenhouse gases, but global acidification, eutrophication, land use and water use. It is far bigger than cutting down on your flights or buying an electric car

- ^ "Indian Vegan Society". Indian Vegan Society. 27 November 2014. Retrieved 22 August 2021.

A vegan always tries to avoid any cruelty and undue exploitation of all animals including humans and protect the environment.

- ^ McGrath, Matt (6 May 2019). "Humans 'threaten 1m species with extinction'". BBC. Retrieved 3 July 2019.

Pushing all this forward, though, are increased demands for food from a growing global population and specifically our growing appetite for meat and fish.

- ^ Watts, Jonathan (6 May 2019). "Human society under urgent threat from loss of Earth's natural life". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 July 2019.

Agriculture and fishing are the primary causes of the deterioration. Food production has increased dramatically since the 1970s, which has helped feed a growing global population and generated jobs and economic growth. But this has come at a high cost. The meat industry has a particularly heavy impact. Grazing areas for cattle account for about 25% of the world's ice-free land and more than 18% of global greenhouse gas emissions.

- ^ Schiermeier, Quirin (8 August 2019). "Eat less meat: UN climate-change report calls for change to human diet". Nature. 572 (7769): 291–292. Bibcode:2019Natur.572..291S. doi:10.1038/d41586-019-02409-7. PMID 31409926. S2CID 199543066.

- ^ "Veg diet plus re-wilding gives 'double climate dividend'". BBC News. 10 January 2022. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- ^ Sun, Zhongxiao; Scherer, Laura; Tukker, Arnold; Spawn-Lee, Seth A.; Bruckner, Martin; Gibbs, Holly K.; Behrens, Paul (January 2022). "Dietary change in high-income nations alone can lead to substantial double climate dividend". Nature Food. 3 (1): 29–37. doi:10.1038/s43016-021-00431-5. ISSN 2662-1355. PMID 37118487. S2CID 245867412.

- ^ "How plant-based diets not only reduce our carbon footprint, but also increase carbon capture". Leiden University. 10 January 2022. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- ^ Carrington, Damian (20 July 2023). "Vegan diet massively cuts environmental damage, study shows". The Guardian. Retrieved 20 July 2023.

- ^ NRCS. 2009. Summary report 2007 national resources inventory. USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service. 123 pp.

- ^ Robert Hart (1996). Forest Gardening. Chelsea Green. p. 45. ISBN 9781603580502.

- ^ University, Carnegie Mellon (14 December 2015). "Vegetarian and "Healthy" Diets Could Be More Harmful to the Environment - News - Carnegie Mellon University". www.cmu.edu. Retrieved 1 April 2024.

- ^ White, Robin R.; Beth Hall, Mary (13 November 2017). "Nutritional and greenhouse gas impacts of removing animals from US agriculture". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 114 (48): E10301 – E10308. Bibcode:2017PNAS..11410301W. doi:10.1073/pnas.1707322114. PMC 5715743. PMID 29133422.

- ^ Van Meerbeek, Koenraad; Svenning, Jens-Christian (12 February 2018). "Causing confusion in the debate about the transition toward a more plant-based diet". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 115 (8): E1701 – E1702. Bibcode:2018PNAS..115E1701V. doi:10.1073/pnas.1720738115. PMC 5828628. PMID 29440444.

- ^ Springmann, Marco; Clark, Michael; Willett, Walter (20 February 2018). "Feedlot diet for Americans that results from a misspecified optimization algorithm". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 115 (8): E1704 – E1705. Bibcode:2018PNAS..115E1704S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1721335115. PMC 5828635. PMID 29440445.

- ^ Shepon, Alon; Eshel, Gidon; Noor, Elad; Milo, Ron (20 February 2018). "The opportunity cost of animal based diets exceeds all food losses". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 115 (15): 3804–3809. Bibcode:2018PNAS..115.3804S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1713820115. PMC 5899434. PMID 29581251.

- ^ White, Robin R.; Beth Hall, Mary (20 February 2018). "Reply to Van Meerbeek and Svenning, Emery, and Springmann et al.: Clarifying assumptions and objectives in evaluating effects of food system shifts on human diets". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 115 (8): E1706 – E1708. Bibcode:2018PNAS..115E1706W. doi:10.1073/pnas.1720895115. PMC 5828631. PMID 29440443.

- ^ Fresán, Ujué; Sabaté, Joan (November 2019). "Vegetarian Diets: Planetary Health and Its Alignment with Human Health". Advances in Nutrition. 10 (Suppl 4): S380 – S388. doi:10.1093/advances/nmz019. ISSN 2161-8313. PMC 6855976. PMID 31728487.

- ^ Heller MC, Keoleian GA. Greenhouse gas emission estimates of U.S. dietary choices and food loss. J Ind Ecol. 2015;19(3):391–401. [Google Scholar]

- ^ Vieux F, Darmon N, Touazi D, Soler LG. Greenhouse gas emissions of self-selected individual diets in France: changing the diet structure or consuming less?. Ecol Econ. 2012;75:91–101. [Google Scholar]

- ^ Reynolds, George (25 October 2019). "Why do people hate vegans?". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 13 September 2024.

External links

[edit]- Eat Less Meat. Save More Wildlife. Center for Biological Diversity

- Meat Eating and Global Warming a list of articles making the vital connection between meat and climate change

- Ecological footprint calculator Two fields are dietary considerations.

- Dr. Ruth Fairchild of the UWIC's report on veganism and CO2-emissions

- The Vegetarian Society UK - information portal

- EarthSave Archived 21 February 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- Vegan Society - Environment

- The rise of eco-veganism. NBC News. 4 July 2019.

- The Climate Activists Who Dismiss Meat Consumption Are Wrong. The New Republic, 31 August 2020