Plant

| Plants Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Clade: | Diaphoretickes |

| Clade: | CAM |

| Clade: | Archaeplastida |

| Kingdom: | Plantae H. F. Copel., 1956 |

| Superdivisions | |

|

See text | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Plants are the eukaryotes that form the kingdom Plantae; they are predominantly photosynthetic. This means that they obtain their energy from sunlight, using chloroplasts derived from endosymbiosis with cyanobacteria to produce sugars from carbon dioxide and water, using the green pigment chlorophyll. Exceptions are parasitic plants that have lost the genes for chlorophyll and photosynthesis, and obtain their energy from other plants or fungi. Most plants are multicellular, except for some green algae.

Historically, as in Aristotle's biology, the plant kingdom encompassed all living things that were not animals, and included algae and fungi. Definitions have narrowed since then; current definitions exclude the fungi and some of the algae. By the definition used in this article, plants form the clade Viridiplantae (green plants), which consists of the green algae and the embryophytes or land plants (hornworts, liverworts, mosses, lycophytes, ferns, conifers and other gymnosperms, and flowering plants). A definition based on genomes includes the Viridiplantae, along with the red algae and the glaucophytes, in the clade Archaeplastida.

There are about 380,000 known species of plants, of which the majority, some 260,000, produce seeds. They range in size from single cells to the tallest trees. Green plants provide a substantial proportion of the world's molecular oxygen; the sugars they create supply the energy for most of Earth's ecosystems, and other organisms, including animals, either eat plants directly or rely on organisms which do so.

Grain, fruit, and vegetables are basic human foods and have been domesticated for millennia. People use plants for many purposes, such as building materials, ornaments, writing materials, and, in great variety, for medicines. The scientific study of plants is known as botany, a branch of biology.

Definition

Taxonomic history

All living things were traditionally placed into one of two groups, plants and animals. This classification dates from Aristotle (384–322 BC), who distinguished different levels of beings in his biology,[5] based on whether living things had a "sensitive soul" or like plants only a "vegetative soul".[6] Theophrastus, Aristotle's student, continued his work in plant taxonomy and classification.[7] Much later, Linnaeus (1707–1778) created the basis of the modern system of scientific classification, but retained the animal and plant kingdoms, naming the plant kingdom the Vegetabilia.[7]

Alternative concepts

When the name Plantae or plant is applied to a specific group of organisms or taxa, it usually refers to one of four concepts. From least to most inclusive, these four groupings are:

| Name(s) | Scope | Organisation | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Land plants, also known as Embryophyta | Plantae sensu strictissimo | Multicellular | Plants in the strictest sense include liverworts, hornworts, mosses, and vascular plants, as well as fossil plants similar to these surviving groups (e.g., Metaphyta Whittaker, 1969,[8] Plantae Margulis, 1971[9]). |

| Green plants, also known as Viridiplantae, Viridiphyta, Chlorobionta or Chloroplastida | Plantae sensu stricto | Some unicellular, some multicellular | Plants in a strict sense include the green algae, and land plants that emerged within them, including stoneworts. The relationships between plant groups are still being worked out, and the names given to them vary considerably. The clade Viridiplantae encompasses a group of organisms that have cellulose in their cell walls, possess chlorophylls a and b and have plastids bound by only two membranes that are capable of photosynthesis and of storing starch. This clade is the main subject of this article (e.g., Plantae Copeland, 1956[10]). |

| Archaeplastida, also known as Plastida or Primoplantae | Plantae sensu lato | Some unicellular, some multicellular | Plants in a broad sense comprise the green plants listed above plus the red algae (Rhodophyta) and the glaucophyte algae (Glaucophyta) that store Floridean starch outside the plastids, in the cytoplasm. This clade includes all of the organisms that eons ago acquired their primary chloroplasts directly by engulfing cyanobacteria (e.g., Plantae Cavalier-Smith, 1981[11]). |

| Old definitions of plant (obsolete) | Plantae sensu amplo | Some unicellular, some multicellular | Plants in the widest sense included the unrelated groups of algae, fungi and bacteria on older, obsolete classifications (e.g. Plantae or Vegetabilia Linnaeus 1751,[12] Plantae Haeckel 1866,[13] Metaphyta Haeckel, 1894,[14] Plantae Whittaker, 1969[8]). |

Evolution

Diversity

There are about 382,000 accepted species of plants,[15] of which the great majority, some 283,000, produce seeds.[16] The table below shows some species count estimates of different green plant (Viridiplantae) divisions. About 85–90% of all plants are flowering plants. Several projects are currently attempting to collect records on all plant species in online databases, e.g. the World Flora Online.[15][17]

Plants range in scale from single-celled organisms such as desmids (from 10 micrometres (μm) across) and picozoa (less than 3 μm across),[18][19] to the largest trees (megaflora) such as the conifer Sequoia sempervirens (up to 120 metres (380 ft) tall) and the angiosperm Eucalyptus regnans (up to 100 m (325 ft) tall).[20]

| Informal group | Division name | Common name | No. of described living species |

|---|---|---|---|

| Green algae | Chlorophyta | Green algae (chlorophytes) | 3800–4300 [21][22] |

| Charophyta | Green algae (e.g. desmids & stoneworts) | 2800–6000 [23][24] | |

| Bryophytes | Marchantiophyta | Liverworts | 6000–8000 [25] |

| Anthocerotophyta | Hornworts | 100–200 [26] | |

| Bryophyta | Mosses | 12000 [27] | |

| Pteridophytes | Lycopodiophyta | Clubmosses | 1200 [28] |

| Polypodiophyta | Ferns, whisk ferns & horsetails | 11000 [28] | |

| Spermatophytes (seed plants) |

Cycadophyta | Cycads | 160 [29] |

| Ginkgophyta | Ginkgo | 1 [30] | |

| Pinophyta | Conifers | 630 [28] | |

| Gnetophyta | Gnetophytes | 70 [28] | |

| Angiospermae | Flowering plants | 258650 [31] |

The naming of plants is governed by the International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants[32] and the International Code of Nomenclature for Cultivated Plants.[33]

Evolutionary history

The ancestors of land plants evolved in water. An algal scum formed on the land 1,200 million years ago, but it was not until the Ordovician, around 450 million years ago, that the first land plants appeared, with a level of organisation like that of bryophytes.[34][35] However, fossils of organisms with a flattened thallus in Precambrian rocks suggest that multicellular freshwater eukaryotes existed over 1000 mya.[36]

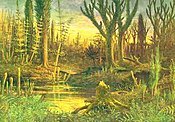

Primitive land plants began to diversify in the late Silurian, around 420 million years ago. Bryophytes, club mosses, and ferns then appear in the fossil record.[37] Early plant anatomy is preserved in cellular detail in an early Devonian fossil assemblage from the Rhynie chert. These early plants were preserved by being petrified in chert formed in silica-rich volcanic hot springs.[38]

By the end of the Devonian, most of the basic features of plants today were present, including roots, leaves and secondary wood in trees such as Archaeopteris.[39][40] The Carboniferous period saw the development of forests in swampy environments dominated by clubmosses and horsetails, including some as large as trees, and the appearance of early gymnosperms, the first seed plants.[41] The Permo-Triassic extinction event radically changed the structures of communities.[42] This may have set the scene for the evolution of flowering plants in the Triassic (~200 million years ago), with an adaptive radiation in the Cretaceous so rapid that Darwin called it an "abominable mystery".[43][44][45] Conifers diversified from the Late Triassic onwards, and became a dominant part of floras in the Jurassic.[46][47]

-

Cross-section of a stem of Rhynia, an early land plant, preserved in Rhynie chert from the early Devonian

-

By the Devonian, plants had adapted to land with roots and woody stems.

-

In the Carboniferous, horsetails such as Asterophyllites proliferated in swampy forests.

-

Adaptive radiation in the Cretaceous created many flowering plants, such as Sagaria in the Ranunculaceae.

Phylogeny

In 2019, a phylogeny based on genomes and transcriptomes from 1,153 plant species was proposed.[48] The placing of algal groups is supported by phylogenies based on genomes from the Mesostigmatophyceae and Chlorokybophyceae that have since been sequenced. Both the "chlorophyte algae" and the "streptophyte algae" are treated as paraphyletic (vertical bars beside phylogenetic tree diagram) in this analysis, as the land plants arose from within those groups.[49][50] The classification of Bryophyta is supported both by Puttick et al. 2018,[51] and by phylogenies involving the hornwort genomes that have also since been sequenced.[52][53]

| Archaeplastida |

|

"chlorophyte algae" "streptophyte algae" | ||||||||||||||||||

Physiology

Plant cells

Plant cells have distinctive features that other eukaryotic cells (such as those of animals) lack. These include the large water-filled central vacuole, chloroplasts, and the strong flexible cell wall, which is outside the cell membrane. Chloroplasts are derived from what was once a symbiosis of a non-photosynthetic cell and photosynthetic cyanobacteria. The cell wall, made mostly of cellulose, allows plant cells to swell up with water without bursting. The vacuole allows the cell to change in size while the amount of cytoplasm stays the same.[54]

Plant structure

Most plants are multicellular. Plant cells differentiate into multiple cell types, forming tissues such as the vascular tissue with specialized xylem and phloem of leaf veins and stems, and organs with different physiological functions such as roots to absorb water and minerals, stems for support and to transport water and synthesized molecules, leaves for photosynthesis, and flowers for reproduction.[55]

Photosynthesis

Plants photosynthesize, manufacturing food molecules (sugars) using energy obtained from light. Plant cells contain chlorophylls inside their chloroplasts, which are green pigments that are used to capture light energy. The end-to-end chemical equation for photosynthesis is:[56]

This causes plants to release oxygen into the atmosphere. Green plants provide a substantial proportion of the world's molecular oxygen, alongside the contributions from photosynthetic algae and cyanobacteria.[57][58][59]

Plants that have secondarily adopted a parasitic lifestyle may lose the genes involved in photosynthesis and the production of chlorophyll.[60]

Growth and repair

Growth is determined by the interaction of a plant's genome with its physical and biotic environment.[61] Factors of the physical or abiotic environment include temperature, water, light, carbon dioxide, and nutrients in the soil.[62] Biotic factors that affect plant growth include crowding, grazing, beneficial symbiotic bacteria and fungi, and attacks by insects or plant diseases.[63]

Frost and dehydration can damage or kill plants. Some plants have antifreeze proteins, heat-shock proteins and sugars in their cytoplasm that enable them to tolerate these stresses.[64] Plants are continuously exposed to a range of physical and biotic stresses which cause DNA damage, but they can tolerate and repair much of this damage.[65]

Reproduction

Plants reproduce to generate offspring, whether sexually, involving gametes, or asexually, involving ordinary growth. Many plants use both mechanisms.[66]

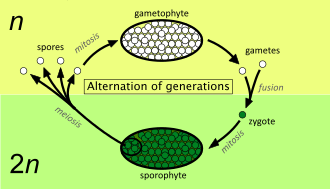

Sexual

When reproducing sexually, plants have complex lifecycles involving alternation of generations. One generation, the sporophyte, which is diploid (with 2 sets of chromosomes), gives rise to the next generation, the gametophyte, which is haploid (with one set of chromosomes). Some plants also reproduce asexually via spores. In some non-flowering plants such as mosses, the sexual gametophyte forms most of the visible plant.[67] In seed plants (gymnosperms and flowering plants), the sporophyte forms most of the visible plant, and the gametophyte is very small. Flowering plants reproduce sexually using flowers, which contain male and female parts: these may be within the same (hermaphrodite) flower, on different flowers on the same plant, or on different plants. The stamens create pollen, which produces male gametes that enter the ovule to fertilize the egg cell of the female gametophyte. Fertilization takes place within the carpels or ovaries, which develop into fruits that contain seeds. Fruits may be dispersed whole, or they may split open and the seeds dispersed individually.[68]

Asexual

Plants reproduce asexually by growing any of a wide variety of structures capable of growing into new plants. At the simplest, plants such as mosses or liverworts may be broken into pieces, each of which may regrow into whole plants. The propagation of flowering plants by cuttings is a similar process. Structures such as runners enable plants to grow to cover an area, forming a clone. Many plants grow food storage structures such as tubers or bulbs which may each develop into a new plant.[69]

Some non-flowering plants, such as many liverworts, mosses and some clubmosses, along with a few flowering plants, grow small clumps of cells called gemmae which can detach and grow.[70][71]

Disease resistance

Plants use pattern-recognition receptors to recognize pathogens such as bacteria that cause plant diseases. This recognition triggers a protective response. The first such plant receptors were identified in rice[72] and in Arabidopsis thaliana.[73]

Genomics

Plants have some of the largest genomes of all organisms.[74] The largest plant genome (in terms of gene number) is that of wheat (Triticum aestivum), predicted to encode ≈94,000 genes[75] and thus almost 5 times as many as the human genome. The first plant genome sequenced was that of Arabidopsis thaliana which encodes about 25,500 genes.[76] In terms of sheer DNA sequence, the smallest published genome is that of the carnivorous bladderwort (Utricularia gibba) at 82 Mb (although it still encodes 28,500 genes)[77] while the largest, from the Norway spruce (Picea abies), extends over 19.6 Gb (encoding about 28,300 genes).[78]

Ecology

Distribution

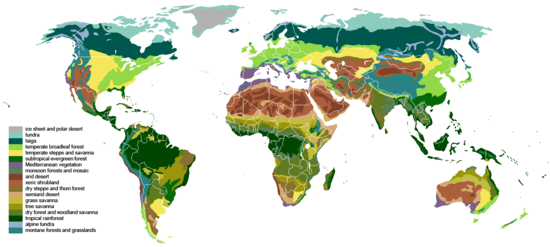

Plants are distributed almost worldwide. While they inhabit many biomes which can be divided into a multitude of ecoregions,[79] only the hardy plants of the Antarctic flora, consisting of algae, mosses, liverworts, lichens, and just two flowering plants, have adapted to the prevailing conditions on that southern continent.[80]

Plants are often the dominant physical and structural component of the habitats where they occur. Many of the Earth's biomes are named for the type of vegetation because plants are the dominant organisms in those biomes, such as grassland, savanna, and tropical rainforest.[81]

Primary producers

The photosynthesis conducted by land plants and algae is the ultimate source of energy and organic material in nearly all ecosystems. Photosynthesis, at first by cyanobacteria and later by photosynthetic eukaryotes, radically changed the composition of the early Earth's anoxic atmosphere, which as a result is now 21% oxygen. Animals and most other organisms are aerobic, relying on oxygen; those that do not are confined to relatively rare anaerobic environments. Plants are the primary producers in most terrestrial ecosystems and form the basis of the food web in those ecosystems.[82] Plants form about 80% of the world biomass at about 450 gigatonnes (4.4×1011 long tons; 5.0×1011 short tons) of carbon.[83]

Ecological relationships

Numerous animals have coevolved with plants; flowering plants have evolved pollination syndromes, suites of flower traits that favour their reproduction. Many, including insect and bird partners, are pollinators, visiting flowers and accidentally transferring pollen in exchange for food in the form of pollen or nectar.[84]

Many animals disperse seeds that are adapted for such dispersal. Various mechanisms of dispersal have evolved. Some fruits offer nutritious outer layers attractive to animals, while the seeds are adapted to survive the passage through the animal's gut; others have hooks that enable them to attach to a mammal's fur.[85] Myrmecophytes are plants that have coevolved with ants. The plant provides a home, and sometimes food, for the ants. In exchange, the ants defend the plant from herbivores and sometimes competing plants. Ant wastes serve as organic fertilizer.[86]

The majority of plant species have fungi associated with their root systems in a mutualistic symbiosis known as mycorrhiza. The fungi help the plants gain water and mineral nutrients from the soil, while the plant gives the fungi carbohydrates manufactured in photosynthesis.[87] Some plants serve as homes for endophytic fungi that protect the plant from herbivores by producing toxins. The fungal endophyte Neotyphodium coenophialum in tall fescue grass has pest status in the American cattle industry.[88]

Many legumes have Rhizobium nitrogen-fixing bacteria in nodules of their roots, which fix nitrogen from the air for the plant to use; in return, the plants supply sugars to the bacteria.[89] Nitrogen fixed in this way can become available to other plants, and is important in agriculture; for example, farmers may grow a crop rotation of a legume such as beans, followed by a cereal such as wheat, to provide cash crops with a reduced input of nitrogen fertilizer.[90]

Some 1% of plants are parasitic. They range from the semi-parasitic mistletoe that merely takes some nutrients from its host, but still has photosynthetic leaves, to the fully-parasitic broomrape and toothwort that acquire all their nutrients through connections to the roots of other plants, and so have no chlorophyll. Full parasites can be extremely harmful to their plant hosts.[91]

Plants that grow on other plants, usually trees, without parasitizing them, are called epiphytes. These may support diverse arboreal ecosystems. Some may indirectly harm their host plant, such as by intercepting light. Hemiepiphytes like the strangler fig begin as epiphytes, but eventually set their own roots and overpower and kill their host. Many orchids, bromeliads, ferns, and mosses grow as epiphytes.[92] Among the epiphytes, the bromeliads accumulate water in their leaf axils; these water-filled cavities can support complex aquatic food webs.[93]

Some 630 species of plants are carnivorous, such as the Venus flytrap (Dionaea muscipula) and sundew (Drosera species). They trap small animals and digest them to obtain mineral nutrients, especially nitrogen and phosphorus.[94]

-

Bee gathering pollen (orange pollen basket on its leg)

-

Hummingbird visiting a flower for nectar

-

Seed dispersal by animals: many hooked Geum urbanum fruits attached to a dog's fur

-

A sundew leaf with sticky hairs curling to trap and digest a fly

Competition

Competition for shared resources reduces a plant's growth.[95][96] Shared resources include sunlight, water and nutrients. Light is a critical resource because it is necessary for photosynthesis.[95] Plants use their leaves to shade other plants from sunlight and grow quickly to maximize their own expose.[95] Water too is essential for photosynthesis; roots compete to maximize water uptake from soil.[97] Some plants have deep roots that are able to locate water stored deep underground, and others have shallower roots that are capable of extending longer distances to collect recent rainwater.[97] Minerals are important for plant growth and development.[98] Common nutrients competed for amongst plants include nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium.[99]

Importance to humans

Food

Human cultivation of plants is the core of agriculture, which in turn has played a key role in the history of world civilizations.[100] Humans depend on flowering plants for food, either directly or as feed in animal husbandry. More broadly, agriculture includes agronomy for arable crops, horticulture for vegetables and fruit, and forestry, including both flowering plants and conifers, for timber.[101][102] About 7,000 species of plant have been used for food, though most of today's food is derived from only 30 species. The major staples include cereals such as rice and wheat, starchy roots and tubers such as cassava and potato, and legumes such as peas and beans. Vegetable oils such as olive oil and palm oil provide lipids, while fruit and vegetables contribute vitamins and minerals to the diet.[103] Coffee, tea, and chocolate are major crops whose caffeine-containing products serve as mild stimulants.[104] The study of plant uses by people is called economic botany or ethnobotany.[105]

Medicines

Medicinal plants are a primary source of organic compounds, both for their medicinal and physiological effects, and for the industrial synthesis of a vast array of organic chemicals.[106] Many hundreds of medicines, as well as narcotics, are derived from plants, both traditional medicines used in herbalism[107][108] and chemical substances purified from plants or first identified in them, sometimes by ethnobotanical search, and then synthesised for use in modern medicine. Modern medicines derived from plants include aspirin, taxol, morphine, quinine, reserpine, colchicine, digitalis and vincristine. Plants used in herbalism include ginkgo, echinacea, feverfew, and Saint John's wort. The pharmacopoeia of Dioscorides, De materia medica, describing some 600 medicinal plants, was written between 50 and 70 CE and remained in use in Europe and the Middle East until around 1600 CE; it was the precursor of all modern pharmacopoeias.[109][110][111]

Nonfood products

Plants grown as industrial crops are the source of a wide range of products used in manufacturing.[112] Nonfood products include essential oils, natural dyes, pigments, waxes, resins, tannins, alkaloids, amber and cork. Products derived from plants include soaps, shampoos, perfumes, cosmetics, paint, varnish, turpentine, rubber, latex, lubricants, linoleum, plastics, inks, and gums. Renewable fuels from plants include firewood, peat and other biofuels.[113][114] The fossil fuels coal, petroleum and natural gas are derived from the remains of aquatic organisms including phytoplankton in geological time.[115] Many of the coal fields date to the Carboniferous period of Earth's history. Terrestrial plants also form type III kerogen, a source of natural gas.[116][117]

Structural resources and fibres from plants are used to construct dwellings and to manufacture clothing. Wood is used for buildings, boats, and furniture, and for smaller items such as musical instruments and sports equipment. Wood is pulped to make paper and cardboard.[118] Cloth is often made from cotton, flax, ramie or synthetic fibres such as rayon, derived from plant cellulose. Thread used to sew cloth likewise comes in large part from cotton.[119]

Ornamental plants

Thousands of plant species are cultivated for their beauty and to provide shade, modify temperatures, reduce wind, abate noise, provide privacy, and reduce soil erosion. Plants are the basis of a multibillion-dollar per year tourism industry, which includes travel to historic gardens, national parks, rainforests, forests with colourful autumn leaves, and festivals such as Japan's[120] and America's cherry blossom festivals.[121]

Plants may be grown indoors as houseplants, or in specialized buildings such as greenhouses. Plants such as Venus flytrap, sensitive plant and resurrection plant are sold as novelties. Art forms specializing in the arrangement of cut or living plant include bonsai, ikebana, and the arrangement of cut or dried flowers. Ornamental plants have sometimes changed the course of history, as in tulipomania.[122]

In science

The traditional study of plants is the science of botany.[123] Basic biological research has often used plants as its model organisms. In genetics, the breeding of pea plants allowed Gregor Mendel to derive the basic laws governing inheritance,[124] and examination of chromosomes in maize allowed Barbara McClintock to demonstrate their connection to inherited traits.[125] The plant Arabidopsis thaliana is used in laboratories as a model organism to understand how genes control the growth and development of plant structures.[126] Tree rings provide a method of dating in archeology, and a record of past climates.[127] The study of plant fossils, or Paleobotany, provides information about the evolutions of plants, paleogeographical reconstructions, and past climate change. Plant fossils can also help determine the age of rocks.[128]

In mythology, religion, and culture

Plants including trees appear in mythology, religion, and literature.[129][130][131] In multiple Indo-European, Siberian, and Native American religions, the world tree motif is depicted as a colossal tree growing on the earth, supporting the heavens, and with its roots reaching into the underworld. It may also appear as a cosmic tree or an eagle and serpent tree.[132][133] Forms of the world tree include the archetypal tree of life, which is in turn connected to the Eurasian concept of the sacred tree.[134] Another widespread ancient motif, found for example in Iran, has a tree of life flanked by a pair of confronted animals.[135]

Flowers are often used as memorials, gifts and to mark special occasions such as births, deaths, weddings and holidays. Flower arrangements may be used to send hidden messages.[136] Plants and especially flowers form the subjects of many paintings.[137][138]

Negative effects

Weeds are commercially or aesthetically undesirable plants growing in managed environments such as in agriculture and gardens.[139] People have spread many plants beyond their native ranges; some of these plants have become invasive, damaging existing ecosystems by displacing native species, and sometimes becoming serious weeds of cultivation.[140]

Some plants that produce windblown pollen, including grasses, invoke allergic reactions in people who suffer from hay fever.[141] Many plants produce toxins to protect themselves from herbivores. Major classes of plant toxins include alkaloids, terpenoids, and phenolics.[142] These can be harmful to humans and livestock by ingestion[143][144] or, as with poison ivy, by contact.[145] Some plants have negative effects on other plants, preventing seedling growth or the growth of nearby plants by releasing allopathic chemicals.[146]

See also

- Aquatic plant

- Carbon dioxide removal

- Ecological succession

- Foodscaping

- Natural environment

- Perennial

- Phytoremediation

- Plant identification

- Plant perception (physiology)

- Terrarium

- World Environment Day

References

- ^ Cavalier-Smith, Tom (1981). "Eukaryote kingdoms: Seven or nine?". BioSystems. 14 (3–4): 461–481. Bibcode:1981BiSys..14..461C. doi:10.1016/0303-2647(81)90050-2. PMID 7337818.

- ^ Lewis, L.A.; McCourt, R.M. (2004). "Green algae and the origin of land plants". American Journal of Botany. 91 (10): 1535–1556. doi:10.3732/ajb.91.10.1535. PMID 21652308.

- ^ Kenrick, Paul; Crane, Peter R. (1997). The origin and early diversification of land plants: A cladistic study. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press. ISBN 978-1-56098-730-7.

- ^ Adl, S. M.; et al. (2005). "The new higher level classification of eukaryotes with emphasis on the taxonomy of protists". Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology. 52 (5): 399–451. doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.2005.00053.x. PMID 16248873. S2CID 8060916.

- ^ Hull, David L. (2010). Science as a Process: An Evolutionary Account of the Social and Conceptual Development of Science. University of Chicago Press. p. 82. ISBN 9780226360492.

- ^ Leroi, Armand Marie (2014). The Lagoon: How Aristotle Invented Science. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 111–119. ISBN 978-1-4088-3622-4.

- ^ a b "Taxonomy and Classification". obo. Retrieved 7 March 2023.

- ^ a b Whittaker, R. H. (1969). "New concepts of kingdoms or organisms" (PDF). Science. 163 (3863): 150–160. Bibcode:1969Sci...163..150W. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.403.5430. doi:10.1126/science.163.3863.150. PMID 5762760. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 November 2017. Retrieved 4 November 2014.

- ^ Margulis, Lynn (1971). "Whittaker's five kingdoms of organisms: minor revisions suggested by considerations of the origin of mitosis". Evolution. 25 (1): 242–245. doi:10.2307/2406516. JSTOR 2406516. PMID 28562945.

- ^ Copeland, H. F. (1956). The Classification of Lower Organisms. Pacific Books. p. 6.

- ^ Cavalier-Smith, Tom (1981). "Eukaryote Kingdoms: Seven or Nine?". BioSystems. 14 (3–4): 461–481. Bibcode:1981BiSys..14..461C. doi:10.1016/0303-2647(81)90050-2. PMID 7337818.

- ^ Linnaeus, Carl (1751). Philosophia botanica (in Latin) (1st ed.). Stockholm: Godofr. Kiesewetter. p. 37. Archived from the original on 23 June 2016.

- ^ Haeckel, Ernst (1866). Generale Morphologie der Organismen. Berlin: Verlag von Georg Reimer. vol. 1: i–xxxii, 1–574, plates I–II; vol. 2: i–clx, 1–462, plates I–VIII.

- ^ Haeckel, Ernst (1894). Die systematische Phylogenie.

- ^ a b "An Online Flora of All Known Plants". The World Flora Online. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- ^ "Numbers of threatened species by major groups of organisms (1996–2010)" (PDF). International Union for Conservation of Nature. 11 March 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 27 April 2011.

- ^ "How many plant species are there in the world? Scientists now have an answer". Mongabay Environmental News. 12 May 2016. Archived from the original on 23 March 2022. Retrieved 28 May 2022.

- ^ Hall, John D.; McCourt, Richard M. (2014). "Chapter 9. Conjugating Green Algae Including Desmids". In Wehr, John D.; Sheath, Robert G.; Kociolek, John Patrick (eds.). Freshwater Algae of North America: Ecology and Classification (2 ed.). Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-12-385876-4.

- ^ Seenivasan, Ramkumar; Sausen, Nicole; Medlin, Linda K.; Melkonian, Michael (26 March 2013). "Picomonas judraskeda Gen. Et Sp. Nov.: The First Identified Member of the Picozoa Phylum Nov., a Widespread Group of Picoeukaryotes, Formerly Known as 'Picobiliphytes'". PLOS One. 8 (3): e59565. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...859565S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0059565. PMC 3608682. PMID 23555709.

- ^ Earle, Christopher J., ed. (2017). "Sequoia sempervirens". The Gymnosperm Database. Archived from the original on 1 April 2016. Retrieved 15 September 2017.

- ^ Van den Hoek, C.; Mann, D.G.; Jahns, H.M. (1995). Algae: An Introduction to Phycology'. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 343, 350, 392, 413, 425, 439, & 448. ISBN 0-521-30419-9.

- ^ Guiry, M.D. & Guiry, G.M. (2011). AlgaeBase : Chlorophyta. National University of Ireland, Galway. Archived from the original on 13 September 2019. Retrieved 26 July 2011.

- ^ Guiry, M.D. & Guiry, G.M. (2011). AlgaeBase : Charophyta. World-wide electronic publication, National University of Ireland, Galway. Archived from the original on 13 September 2019. Retrieved 26 July 2011.

- ^ Van den Hoek, C.; Mann, D.G.; Jahns, H.M (1995). Algae: An Introduction to Phycology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 457, 463, & 476. ISBN 0-521-30419-9.

- ^ Crandall-Stotler, Barbara; Stotler, Raymond E. (2000). "Morphology and classification of the Marchantiophyta". In Shaw, A. Jonathan; Goffinet, Bernard (eds.). Bryophyte Biology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 21. ISBN 0-521-66097-1.

- ^ Schuster, Rudolf M. (1992). The Hepaticae and Anthocerotae of North America. Vol. VI. Chicago: Field Museum of Natural History. pp. 712–713. ISBN 0-914868-21-7.

- ^ Goffinet, Bernard; William R. Buck (2004). "Systematics of the Bryophyta (Mosses): From molecules to a revised classification". Monographs in Systematic Botany. 98: 205–239.

- ^ a b c d Raven, Peter H.; Evert, Ray F.; Eichhorn, Susan E. (2005). Biology of Plants (7th ed.). New York: W. H. Freeman and Company. ISBN 978-0-7167-1007-3.

- ^ Gifford, Ernest M.; Foster, Adriance S. (1988). Morphology and Evolution of Vascular Plants (3rd ed.). New York: W. H. Freeman and Company. p. 358. ISBN 978-0-7167-1946-5.

- ^ Taylor, Thomas N.; Taylor, Edith L. (1993). The Biology and Evolution of Fossil Plants. New Jersey: Prentice Hall. p. 636. ISBN 978-0-13-651589-0.

- ^ International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources, 2006. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species:Summary Statistics Archived 27 June 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants". www.iapt-taxon.org. Retrieved 4 March 2023.

- ^ Gledhill, D. (2008). The Names of Plants. Cambridge University Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-5218-6645-3.

- ^ Taylor, Thomas N. (November 1988). "The Origin of Land Plants: Some Answers, More Questions". Taxon. 37 (4): 805–833. doi:10.2307/1222087. JSTOR 1222087.

- ^ Ciesielski, Paul F. "Transition of plants to land". Archived from the original on 2 March 2008.

- ^ Strother, Paul K.; Battison, Leila; Brasier, Martin D.; Wellman, Charles H. (26 May 2011). "Earth's earliest non-marine eukaryotes". Nature. 473 (7348): 505–509. Bibcode:2011Natur.473..505S. doi:10.1038/nature09943. PMID 21490597. S2CID 4418860.

- ^ Crang, Richard; Lyons-Sobaski, Sheila; Wise, Robert (2018). Plant Anatomy: A Concept-Based Approach to the Structure of Seed Plants. Springer. p. 17. ISBN 9783319773155.

- ^ Garwood, Russell J.; Oliver, Heather; Spencer, Alan R. T. (2019). "An introduction to the Rhynie chert". Geological Magazine. 157 (1): 47–64. doi:10.1017/S0016756819000670. S2CID 182210855.

- ^ Beck, C. B. (1960). "The identity of Archaeopteris and Callixylon". Brittonia. 12 (4): 351–368. Bibcode:1960Britt..12..351B. doi:10.2307/2805124. JSTOR 2805124. S2CID 27887887.

- ^ Rothwell, G. W.; Scheckler, S. E.; Gillespie, W. H. (1989). "Elkinsia gen. nov., a Late Devonian gymnosperm with cupulate ovules". Botanical Gazette. 150 (2): 170–189. doi:10.1086/337763. JSTOR 2995234. S2CID 84303226.

- ^ "Plants". British Geological Survey. Retrieved 9 March 2023.

- ^ McElwain, Jennifer C.; Punyasena, Surangi W. (2007). "Mass extinction events and the plant fossil record". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 22 (10): 548–557. Bibcode:2007TEcoE..22..548M. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2007.09.003. PMID 17919771.

- ^ Friedman, William E. (January 2009). "The meaning of Darwin's "abominable mystery"". American Journal of Botany. 96 (1): 5–21. doi:10.3732/ajb.0800150. PMID 21628174.

- ^ Berendse, Frank; Scheffer, Marten (2009). "The angiosperm radiation revisited, an ecological explanation for Darwin's 'abominable mystery'". Ecology Letters. 12 (9): 865–872. Bibcode:2009EcolL..12..865B. doi:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2009.01342.x. PMC 2777257. PMID 19572916.

- ^ Herendeen, Patrick S.; Friis, Else Marie; Pedersen, Kaj Raunsgaard; Crane, Peter R. (3 March 2017). "Palaeobotanical redux: revisiting the age of the angiosperms". Nature Plants. 3 (3): 17015. doi:10.1038/nplants.2017.15. PMID 28260783. S2CID 205458714.

- ^ Atkinson, Brian A.; Serbet, Rudolph; Hieger, Timothy J.; Taylor, Edith L. (October 2018). "Additional evidence for the Mesozoic diversification of conifers: Pollen cone of Chimaerostrobus minutus gen. et sp. nov. (Coniferales), from the Lower Jurassic of Antarctica". Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology. 257: 77–84. Bibcode:2018RPaPa.257...77A. doi:10.1016/j.revpalbo.2018.06.013. S2CID 133732087.

- ^ Leslie, Andrew B.; Beaulieu, Jeremy; Holman, Garth; Campbell, Christopher S.; Mei, Wenbin; Raubeson, Linda R.; Mathews, Sarah (September 2018). "An overview of extant conifer evolution from the perspective of the fossil record". American Journal of Botany. 105 (9): 1531–1544. doi:10.1002/ajb2.1143. PMID 30157290. S2CID 52120430.

- ^ Leebens-Mack, M.; Barker, M.; Carpenter, E.; et al. (2019). "One thousand plant transcriptomes and the phylogenomics of green plants". Nature. 574 (7780): 679–685. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1693-2. PMC 6872490. PMID 31645766.

- ^ Liang, Zhe; et al. (2019). "Mesostigma viride Genome and Transcriptome Provide Insights into the Origin and Evolution of Streptophyta". Advanced Science. 7 (1): 1901850. doi:10.1002/advs.201901850. PMC 6947507. PMID 31921561.

- ^ Wang, Sibo; et al. (2020). "Genomes of early-diverging streptophyte algae shed light on plant terrestrialization". Nature Plants. 6 (2): 95–106. doi:10.1038/s41477-019-0560-3. PMC 7027972. PMID 31844283.

- ^ Puttick, Mark; et al. (2018). "The Interrelationships of Land Plants and the Nature of the Ancestral Embryophyte". Current Biology. 28 (5): 733–745. Bibcode:2018CBio...28E.733P. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2018.01.063. hdl:10400.1/11601. PMID 29456145.

- ^ Zhang, Jian; et al. (2020). "The hornwort genome and early land plant evolution". Nature Plants. 6 (2): 107–118. doi:10.1038/s41477-019-0588-4. PMC 7027989. PMID 32042158.

- ^ Li, Fay Wei; et al. (2020). "Anthoceros genomes illuminate the origin of land plants and the unique biology of hornworts". Nature Plants. 6 (3): 259–272. doi:10.1038/s41477-020-0618-2. PMC 8075897. PMID 32170292.

- ^ "Plant Cells, Chloroplasts, and Cell Walls". Scitable by Nature Education. Retrieved 7 March 2023.

- ^ Farabee, M. C. "Plants and their Structure". Maricopa Community Colleges. Archived from the original on 22 October 2006. Retrieved 7 March 2023.

- ^ Newton, John (4 March 2023). "What Is the Photosynthesis Equation?". Sciencing. Retrieved 7 March 2023.

- ^ Field, C. B.; Behrenfeld, M. J.; Randerson, J. T.; Falkowski, P. (1998). "Primary production of the biosphere: Integrating terrestrial and oceanic components". Science. 281 (5374): 237–240. Bibcode:1998Sci...281..237F. doi:10.1126/science.281.5374.237. PMID 9657713. Archived from the original on 25 September 2018. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- ^ Tivy, Joy (2014). Biogeography: A Study of Plants in the Ecosphere. Routledge. pp. 31, 108–110. ISBN 978-1-317-89723-1. OCLC 1108871710.

- ^ Qu, Xiao-Jian; Fan, Shou-Jin; Wicke, Susann; Yi, Ting-Shuang (2019). "Plastome reduction in the only parasitic gymnosperm Parasitaxus is due to losses of photosynthesis but not housekeeping genes and apparently involves the secondary gain of a large inverted repeat". Genome Biology and Evolution. 11 (10): 2789–2796. doi:10.1093/gbe/evz187. PMC 6786476. PMID 31504501.

- ^ Baucom, Regina S.; Heath, Katy D.; Chambers, Sally M. (2020). "Plant–environment interactions from the lens of plant stress, reproduction, and mutualisms". American Journal of Botany. 107 (2). Wiley: 175–178. doi:10.1002/ajb2.1437. PMC 7186814. PMID 32060910.

- ^ "Abiotic Factors". National Geographic. Retrieved 7 March 2023.

- ^ Bareja, Ben (10 April 2022). "Biotic Factors and Their Interaction With Plants". Crops Review. Retrieved 7 March 2023.

- ^ Ambroise, Valentin; Legay, Sylvain; Guerriero, Gea; et al. (18 October 2019). "The Roots of Plant Frost Hardiness and Tolerance". Plant and Cell Physiology. 61 (1): 3–20. doi:10.1093/pcp/pcz196. PMC 6977023. PMID 31626277.

- ^ Roldán-Arjona, T.; Ariza, R. R. (2009). "Repair and tolerance of oxidative DNA damage in plants". Mutation Research. 681 (2–3): 169–179. Bibcode:2009MRRMR.681..169R. doi:10.1016/j.mrrev.2008.07.003. PMID 18707020. Archived from the original on 23 September 2017. Retrieved 22 September 2017.

- ^ Yang, Yun Young; Kim, Jae Geun (24 November 2016). "The optimal balance between sexual and asexual reproduction in variable environments: a systematic review". Journal of Ecology and Environment. 40 (1). doi:10.1186/s41610-016-0013-0. hdl:10371/100354. S2CID 257092048.

- ^ "How Do Plants With Spores Reproduce?". Sciencing. 23 April 2018. Retrieved 7 March 2023.

- ^ Barrett, S. C. H. (2002). "The evolution of plant sexual diversity" (PDF). Nature Reviews Genetics. 3 (4): 274–284. doi:10.1038/nrg776. PMID 11967552. S2CID 7424193. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 May 2013. Retrieved 7 March 2023.

- ^ "Asexual reproduction in plants". BBC Bitesize. Retrieved 7 March 2023.

- ^ Kato, Hirotaka; Yasui, Yukiko; Ishizaki, Kimitsune (19 June 2020). "Gemma cup and gemma development in Marchantia polymorpha". New Phytologist. 228 (2): 459–465. doi:10.1111/nph.16655. PMID 32390245. S2CID 218583032.

- ^ Moody, Amber; Diggle, Pamela K.; Steingraeber, David A. (1999). "Developmental analysis of the evolutionary origin of vegetative propagules in Mimulus gemmiparus (Scrophulariaceae)". American Journal of Botany. 86 (11): 1512–1522. doi:10.2307/2656789. JSTOR 2656789. PMID 10562243.

- ^ Song, W. Y.; et al. (1995). "A receptor kinase-like protein encoded by the rice disease resistance gene, XA21". Science. 270 (5243): 1804–1806. Bibcode:1995Sci...270.1804S. doi:10.1126/science.270.5243.1804. PMID 8525370. S2CID 10548988. Archived from the original on 7 November 2018. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- ^ Gomez-Gomez, L.; et al. (2000). "FLS2: an LRR receptor-like kinase involved in the perception of the bacterial elicitor flagellin in Arabidopsis". Molecular Cell. 5 (6): 1003–1011. doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80265-8. PMID 10911994.

- ^ Michael, Todd P.; Jackson, Scott (1 July 2013). "The First 50 Plant Genomes". The Plant Genome. 6 (2): 0. doi:10.3835/plantgenome2013.03.0001in.

- ^ Brenchley, Rachel; Spannagl, Manuel; Pfeifer, Matthias; et al. (29 November 2012). "Analysis of the bread wheat genome using whole-genome shotgun sequencing". Nature. 491 (7426): 705–710. Bibcode:2012Natur.491..705B. doi:10.1038/nature11650. PMC 3510651. PMID 23192148.

- ^ Arabidopsis Genome Initiative (14 December 2000). "Analysis of the genome sequence of the flowering plant Arabidopsis thaliana". Nature. 408 (6814): 796–815. Bibcode:2000Natur.408..796T. doi:10.1038/35048692. PMID 11130711.

- ^ Ibarra-Laclette, Enrique; Lyons, Eric; Hernández-Guzmán, Gustavo; et al. (6 June 2013). "Architecture and evolution of a minute plant genome". Nature. 498 (7452): 94–98. Bibcode:2013Natur.498...94I. doi:10.1038/nature12132. PMC 4972453. PMID 23665961.

- ^ Nystedt, Björn; Street, Nathaniel R.; Wetterbom, Anna; et al. (30 May 2013). "The Norway spruce genome sequence and conifer genome evolution". Nature. 497 (7451): 579–584. Bibcode:2013Natur.497..579N. doi:10.1038/nature12211. hdl:1854/LU-4110028. PMID 23698360.

- ^ Olson, David M.; Dinerstein, Eric; Wikramanayake, Eric D.; et al. (2001). "Terrestrial Ecoregions of the World: A New Map of Life on Earth". BioScience. 51 (11): 933. doi:10.1641/0006-3568(2001)051[0933:teotwa]2.0.co;2. S2CID 26844434.

- ^ Schulze, Ernst-Detlef; Beck, Erwin; Buchmann, Nina; Clemens, Stephan; Müller-Hohenstein, Klaus; Scherer-Lorenzen, Michael (3 May 2018). "Spatial Distribution of Plants and Plant Communities". Plant Ecology. Springer. pp. 657–688. doi:10.1007/978-3-662-56233-8_18. ISBN 978-3-662-56231-4.

- ^ "The Five Major Types of Biomes". National Geographic Education. Retrieved 7 March 2023.

- ^ Gough, C. M. (2011). "Terrestrial Primary Production: Fuel for Life". Nature Education Knowledge. 3 (10): 28.

- ^ Bar-On, Y. M.; Phillips, R.; Milo, R. (June 2018). "The biomass distribution on Earth" (PDF). PNAS. 115 (25): 6506–6511. Bibcode:2018PNAS..115.6506B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1711842115. PMC 6016768. PMID 29784790. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 February 2022. Retrieved 12 October 2020.

- ^ Lunau, Klaus (2004). "Adaptive radiation and coevolution — pollination biology case studies". Organisms Diversity & Evolution. 4 (3): 207–224. Bibcode:2004ODivE...4..207L. doi:10.1016/j.ode.2004.02.002.

- ^ Schaefer, H. Martin; Ruxton, Graeme D. (7 April 2011). "Animals as seed dispersers". Plant-Animal Communication. Oxford University Press. pp. 48–67. doi:10.1093/acprof:osobl/9780199563609.003.0003. ISBN 978-0-19-956360-9.

- ^ Speight, Martin R.; Hunter, Mark D.; Watt, Allan D. (2008). Ecology of Insects (2nd ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 212–216. ISBN 978-1-4051-3114-8.

- ^ Deacon, Jim. "The Microbial World: Mycorrhizas". bio.ed.ac.uk (archived). Archived from the original on 27 April 2018. Retrieved 11 January 2019.

- ^ Lyons, P. C.; Plattner, R. D.; Bacon, C. W. (1986). "Occurrence of peptide and clavine ergot alkaloids in tall fescue grass". Science. 232 (4749): 487–489. Bibcode:1986Sci...232..487L. doi:10.1126/science.3008328. PMID 3008328.

- ^ Fullick, Ann (2006). Feeding Relationships. Heinemann-Raintree Library. ISBN 978-1-4034-7521-3.

- ^ Wagner, Stephen (2011). "Biological Nitrogen Fixation". Nature Education Knowledge. Archived from the original on 17 March 2020. Retrieved 6 November 2017.

- ^ Kokla, Anna; Melnyk, Charles W. (2018). "Developing a thief: Haustoria formation in parasitic plants". Developmental Biology. 442 (1): 53–59. doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2018.06.013. PMID 29935146. S2CID 49394142.

- ^ Zotz, Gerhard (2016). Plants on Plants: the biology of vascular epiphytes. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International. pp. 1–12 (Introduction), 267–272 (Epilogue: The Epiphyte Syndrome). ISBN 978-3-319-81847-4. OCLC 959553277.

- ^ Frank, Howard (October 2000). "Bromeliad Phytotelmata". University of Florida. Archived from the original on 20 August 2009.

- ^ Ellison, Aaron; Adamec, Lubomir (2018). "Introduction: What is a carnivorous plant?". Carnivorous Plants: Physiology, Ecology, and Evolution (First ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 3–4. ISBN 978-0-1988-3372-7.

- ^ a b c Keddy, Paul A.; Cahill, James (2012). "Competition in Plant Communities". Oxford Bibliographies Online. doi:10.1093/obo/9780199830060-0009. ISBN 978-0-19-983006-0. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ Pocheville, Arnaud (January 2015). "The Ecological Niche: History and Recent Controversies". Handbook of Evolutionary Thinking in the Sciences. pp. 547–586. doi:10.1007/978-94-017-9014-7_26. ISBN 978-94-017-9013-0. Archived from the original on 15 January 2022. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ a b Casper, Brenda B.; Jackson, Robert B. (November 1997). "Plant Competition Underground". Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 28 (1): 545–570. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.28.1.545. Archived from the original on 25 May 2021. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ Craine, Joseph M.; Dybzinski, Ray (2013). "Mechanisms of plant competition for nutrients, water and light". Functional Ecology. 27 (4): 833–840. Bibcode:2013FuEco..27..833C. doi:10.1111/1365-2435.12081. S2CID 83776710.

- ^ Oborny, Beáta; Kun, Ádám; Czárán, Tamás; Bokros, Szilárd (2000). "The Effect of Clonal Integration on Plant Competition for Mosaic Habitat Space". Ecology. 81 (12): 3291–3304. doi:10.1890/0012-9658(2000)081[3291:TEOCIO]2.0.CO;2. Archived from the original on 18 April 2021. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

- ^ Wrench, Jason S. (9 January 2013). Workplace Communication for the 21st Century: Tools and Strategies that Impact the Bottom Line [2 volumes]: Tools and Strategies That Impact the Bottom Line. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-3133-9632-8.

- ^ Agricultural Research Service (1903). Report on the Agricultural Experiment Stations. U.S. Government Printing Office.

- ^ "The Development of Agriculture". National Geographic. 2016. Archived from the original on 14 April 2016. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ "Food and drink". Kew Gardens. Archived from the original on 28 March 2014. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ Hopper, Stephen D. (2015). "Royal Botanic Gardens Kew". Encyclopedia of Life Sciences. Wiley. pp. 1–9. doi:10.1002/9780470015902.a0024933. ISBN 9780470015902.

- ^ Kochhar, S. L. (31 May 2016). "Ethnobotany". Economic Botany: A Comprehensive Study. Cambridge University Press. p. 644. ISBN 978-1-3166-7539-7.

- ^ "Chemicals from Plants". Cambridge University Botanic Garden. Archived from the original on 9 December 2017. Retrieved 9 December 2017. The details of each plant and the chemicals it yields are described in the linked subpages.

- ^ Tapsell, L. C.; Hemphill, I.; Cobiac, L. (August 2006). "Health benefits of herbs and spices: the past, the present, the future". Medical Journal of Australia. 185 (4 Supplement): S4–24. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2006.tb00548.x. hdl:2440/22802. PMID 17022438. S2CID 9769230. Archived from the original on 31 October 2020. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ^ Lai, P. K.; Roy, J. (June 2004). "Antimicrobial and chemopreventive properties of herbs and spices". Current Medicinal Chemistry. 11 (11): 1451–1460. doi:10.2174/0929867043365107. PMID 15180577.

- ^ "Greek Medicine". National Institutes of Health, USA. 16 September 2002. Archived from the original on 9 November 2013. Retrieved 22 May 2014.

- ^ Hefferon, Kathleen (2012). Let Thy Food Be Thy Medicine. Oxford University Press. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-1998-7398-2. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- ^ Rooney, Anne (2009). The Story of Medicine. Arcturus Publishing. p. 143. ISBN 978-1-8485-8039-8. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- ^ "Industrial Crop Production". Grace Communications Foundation. 2016. Archived from the original on 10 June 2016. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- ^ "Industrial Crops and Products An International Journal". Elsevier. Archived from the original on 2 October 2017. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- ^ Cruz, Von Mark V.; Dierig, David A. (2014). Industrial Crops: Breeding for BioEnergy and Bioproducts. Springer. pp. 9 and passim. ISBN 978-1-4939-1447-0. Archived from the original on 22 April 2017. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ Sato, Motoaki (1990). "Thermochemistry of the formation of fossil fuels". Fluid-Mineral Interactions: A Tribute to H. P. Eugster, Special Publication No. 2 (PDF). The Geochemical Society. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 September 2015. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ Miller, G.; Spoolman, Scott (2007). Environmental Science: Problems, Connections and Solutions. Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-0-495-38337-6. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- ^ Ahuja, Satinder (2015). Food, Energy, and Water: The Chemistry Connection. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-12-800374-9. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- ^ Sixta, Herbert, ed. (2006). Handbook of pulp. Vol. 1. Winheim, Germany: Wiley-VCH. p. 9. ISBN 978-3-527-30997-9.

- ^ "Natural fibres". Discover Natural Fibres. 2009. Archived from the original on 20 July 2016.

- ^ Sosnoski, Daniel (1996). Introduction to Japanese culture. Tuttle. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-8048-2056-1. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- ^ "History of the Cherry Blossom Trees and Festival". National Cherry Blossom Festival: About. National Cherry Blossom Festival. Archived from the original on 14 March 2016. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- ^ Lambert, Tim (2014). "A Brief History of Gardening". BBC. Archived from the original on 9 June 2016. Retrieved 21 June 2016.

- ^ Mason, Matthew G. "Introduction to Botany". Environmental Science. Retrieved 6 June 2023.

- ^ Blumberg, Roger B. "Mendel's Paper in English". Archived from the original on 13 January 2016. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- ^ "Barbara McClintock: A Brief Biographical Sketch". WebCite. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 21 June 2016.

- ^ "About Arabidopsis". TAIR. Archived from the original on 22 October 2016. Retrieved 21 June 2016.

- ^ Bauer, Bruce (29 November 2018). "How Tree Rings Tell Time and Climate History". Climate.gov. Archived from the original on 12 August 2021.

- ^ Cleal, Christopher J.; Thomas, Barry A. (2019). Introduction to Plant Fossils. Cambridge University Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-1-1084-8344-5.

- ^ Leitten, Rebecca Rose. "Plant Myths and Legends". Cornell University Liberty Hyde Bailey Conservatory. Archived from the original on 7 August 2016. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- ^ "Seven of the most sacred plants in the world". BBC. Archived from the original on 20 September 2020. Retrieved 12 October 2020.

- ^ "Literary Plants". Nature Plants. 1 (11): 15181. 3 November 2015. doi:10.1038/nplants.2015.181. PMID 27251545.

- ^ Annus, Amar (2009). "Review Article. The Folk-Tales of Iraq and the Literary Traditions of Ancient Mesopotamia". Journal of Ancient Near Eastern Religions. 9 (1): 87–99. doi:10.1163/156921209X449170.

- ^ Wittkower, Rudolf (1939). "Eagle and Serpent. A Study in the Migration of Symbols". Journal of the Warburg Institute. 2 (4): 293–325. doi:10.2307/750041. JSTOR 750041. S2CID 195042671.

- ^ Giovino, Mariana (2007). The Assyrian Sacred Tree: A History of Interpretations. Saint-Paul. p. 129. ISBN 978-3-7278-1602-4.

- ^ "Textile with Birds and Horned Quadrupeds Flanking a Tree of Life". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 21 August 2023.

- ^ Fogden, Michael; Fogden, Patricia (2018). The Natural History of Flowers. Texas A&M University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-6234-9644-9.

- ^ "Botanical Imagery in European Painting". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- ^ Raymond, Francine (12 March 2013). "Why botanical art is still blooming today". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- ^ Harlan, J. R.; deWet, J. M. (1965). "Some thoughts about weeds". Economic Botany. 19 (1): 16–24. doi:10.1007/BF02971181. S2CID 28399160.

- ^ Davis, Mark A.; Thompson, Ken (2000). "Eight Ways to be a Colonizer; Two Ways to be an Invader: A Proposed Nomenclature Scheme for Invasion Ecology". Bulletin of the Ecological Society of America. 81 (3). Ecological Society of America: 226–230.

- ^ "Cause of Environmental Allergies". NIAID. 22 April 2015. Archived from the original on 17 June 2015. Retrieved 17 June 2015.

- ^ "Biochemical defenses: secondary metabolites". Plant Defense Systems & Medicinal Botany. Archived from the original on 3 July 2007. Retrieved 21 May 2007.

- ^ Bevan-Jones, Robert (1 August 2009). Poisonous Plants: A Cultural and Social History. Windgather Press. ISBN 978-1-909686-22-9.

- ^ Livestock-Poisoning Plants of California. UCANR Publications. ISBN 978-1-60107-674-8.

- ^ Crosby, Donald G. (1 April 2004). The Poisoned Weed: Plants Toxic to Skin. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-028870-9.

- ^ Grodzinskii, A. M. (1 March 2016). Allelopathy in the Life of Plants and their Communities. Scientific Publishers. ISBN 978-93-86102-04-1.

Further reading

General:

- Evans, L.T. (1998). Feeding the Ten Billion – Plants and Population Growth. Cambridge University Press.ISBN 0-521-64685-5.

- Kenrick, Paul; Crane, Peter R. (1997). The Origin and Early Diversification of Land Plants: A Cladistic Study. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press. ISBN 1-56098-730-8.

- Raven, Peter H.; Evert, Ray F.; Eichhorn, Susan E. (2005). Biology of Plants (7th ed.). New York: W.H. Freeman and Company. ISBN 0-7167-1007-2.

- Taylor, Thomas N.; Taylor, Edith L. (1993). The Biology and Evolution of Fossil Plants. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-651589-4.

Species estimates and counts:

- International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) Species Survival Commission (2004). IUCN Red List The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

- Prance, G. T. (2001). "Discovering the Plant World". Taxon. 50 (2, Golden Jubilee Part 4): 345–359. doi:10.2307/1223885. JSTOR 1223885.

External links

- Index Nominum Algarum

- Interactive Cronquist classification. Archived 10 February 2006.

- Plant Resources of Tropical Africa. Archived 11 June 2010.

- Tree of Life. Archived 9 March 2022 at the Wayback Machine.

- Botanical and vegetation databases

- African Plants Initiative database

- Australia

- Chilean plants at Chilebosque

- e-Floras (Flora of China, Flora of North America and others). Archived 19 February 2022 at the Wayback Machine.

- Flora Europaea

- Flora of Central Europe (in German)

- Flora of North America. Archived 19 February 2022 at the Wayback Machine.

- List of Japanese Wild Plants Online. Archived 16 March 2022 at the Wayback Machine.

- Meet the Plants-National Tropical Botanical Garden. Archived 16 June 2007.

- Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center – Native Plant Information Network at University of Texas, Austin

- United States Department of Agriculture not limited to continental US species.

![{\displaystyle {\ce {6CO2{}+6H2O{}->[{\text{light}}]C6H12O6{}+6O2{}}}}](https://wikimedia.riteme.site/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/100302228047a00799cc68db892940dd5e3adc9e)