Van Morrison

Van Morrison | |

|---|---|

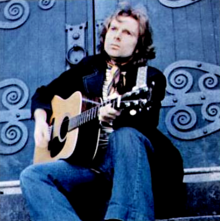

Morrison in 2015 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | George Ivan Morrison |

| Also known as | Van the Man

The Belfast Cowboy |

| Born | 31 August 1945 Bloomfield, Belfast, Northern Ireland |

| Genres | |

| Occupations |

|

| Instruments |

|

| Discography | Van Morrison discography |

| Years active | 1958–present |

| Labels |

|

| Formerly of | |

| Website | vanmorrison |

Sir George Ivan Morrison OBE (born 31 August 1945) is a Northern Irish singer-songwriter and musician whose recording career started in the 1960s.

Morrison's albums have performed well in the UK and Ireland, with more than 40 reaching the UK top 40, as well as internationally, including in Germany, the Netherlands and Switzerland. He has scored top ten albums in the UK in four consecutive decades, following the success of 2021's Latest Record Project, Volume 1.[1] Eighteen of his albums have reached the top 40 in the United States, twelve of them between 1997 and 2017.[2] Since turning 70 in 2015, he has released – on average – more than an album a year. His accolades, include two Grammy Awards,[3] the 1994 Brit Award for Outstanding Contribution to Music, the 2017 Americana Music Lifetime Achievement Award for Songwriting and he has been inducted into both the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and the Songwriters Hall of Fame. In 2016 he was knighted for services to the music industry and to tourism in Northern Ireland.[4][5]

Morrison began performing as a teenager in the late 1950s, playing a variety of instruments including guitar, harmonica, keyboards and saxophone for various Irish showbands, covering the popular hits of that time. Known as "Van the Man" to his fans,[6] Morrison rose to prominence in the mid-1960s as the lead singer of the Belfast R&B band Them, with whom he wrote and recorded "Gloria", which became a garage band staple. His solo career started under the pop-hit-oriented guidance of Bert Berns with the release of the hit single "Brown Eyed Girl" in 1967.

After Berns's death, Warner Bros. Records bought Morrison's contract and allowed him three sessions to record Astral Weeks (1968).[7] While initially a poor seller, the album has come to be regarded as a classic.[8] Moondance (1970) established Morrison as a major artist,[9] and he built on his reputation throughout the 1970s with a series of acclaimed albums and live performances.

Much of Morrison's music is structured around the conventions of soul music and early rhythm and blues. An equal part of his catalogue consists of lengthy, spiritually inspired musical journeys that show the influence of Celtic tradition, jazz and stream of consciousness narrative, of which Astral Weeks is a prime example.[10][11] The two strains together are sometimes referred to as "Celtic soul",[12] and his music has been described as attaining "a kind of violent transcendence".[13]

Life and career

[edit]Early life and musical roots: 1945–1964

[edit]George Ivan Morrison was born on 31 August 1945,[14] at 125 Hyndford Street, Bloomfield, Belfast, Northern Ireland, as the only child of George Morrison, a shipyard electrician, and Violet Morrison (née Stitt), who had been a singer and tap dancer in her youth. The previous occupant of the house was the writer Lee Child's father.[15] Morrison's family were working class Protestants descended from the Ulster Scots population that settled in Belfast.[16][17][18] From 1950 to 1956, Morrison, who began to be known as "Van" during this time, attended Elmgrove Primary School.[19] His father had what was at the time one of the largest record collections in Northern Ireland (acquired during his time in Detroit, Michigan, in the early 1950s)[20] and the young Morrison grew up listening to artists such as Jelly Roll Morton, Ray Charles, Lead Belly, Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee and Solomon Burke;[19][21] of whom he later said, "If it weren't for guys like Ray and Solomon, I wouldn't be where I am today. Those guys were the inspiration that got me going. If it wasn't for that kind of music, I couldn't do what I'm doing now."[22]

His father's record collection exposed him to various musical genres, such as the blues of Muddy Waters; the gospel of Mahalia Jackson; the jazz of Charlie Parker; the folk music of Woody Guthrie; and country music from Hank Williams and Jimmie Rodgers,[19] while the first record he ever bought was by blues musician Sonny Terry.[23] When Lonnie Donegan had a hit with "Rock Island Line", written by Huddie Ledbetter (Lead Belly), Morrison felt he was familiar with and able to connect with skiffle music as he had been hearing Lead Belly before that.[24][25]

Morrison's father bought him his first acoustic guitar when he was 11, and he learned to play rudimentary chords from the song book The Carter Family Style, edited by Alan Lomax.[26] In 1957, at the age of twelve, Morrison formed his first band,[27] a skiffle group, "The Sputniks", named after the satellite, Sputnik 1, that had been launched in October of that year by the Soviet Union.[28] In 1958, the band played at some of the local cinemas, and Morrison took the lead, contributing most of the singing and arranging. Other short-lived groups followed – at 14, he formed Midnight Special, another modified skiffle band and played at a school concert.[26] Then, when he heard Jimmy Giuffre playing saxophone on "The Train and The River", he talked his father into buying him a tenor saxophone,[29] and took saxophone and music reading lessons from jazz musician George Cassidy, who Morrison saw as a "big inspiration", and they became friends, he also grew up with him on Hyndford Street.[30][31][32] Now playing the saxophone, Morrison joined with various local bands, including one called Deanie Sands and the Javelins, with whom he played guitar and shared singing. The line-up of the band was lead vocalist Deanie Sands, guitarist George Jones, and drummer and vocalist Roy Kane.[33] Later the four main musicians of the Javelins, with the addition of Wesley Black as pianist, became known as the Monarchs.[34]

Morrison attended Orangefield Boys Secondary School, leaving in July 1960 with no qualifications.[35] As a member of a working-class community, he was expected to get a regular full-time job,[34] so after several short apprenticeship positions, he settled into a job as a window cleaner—later alluded to in his songs "Cleaning Windows" and "Saint Dominic's Preview".[36] However, he had been developing his musical interests from an early age and continued playing with the Monarchs part-time. Young Morrison also played with the Harry Mack Showband, the Great Eight, with his older workplace friend, Geordie (G. D.) Sproule, whom he later named as one of his biggest influences.[37]

At age 17, Morrison toured Europe for the first time with the Monarchs, now calling themselves the International Monarchs. This Irish showband,[38] with Morrison playing saxophone, guitar and harmonica, in addition to back-up duty on bass and drums, toured seamy clubs and US Army bases in Scotland, England and Germany, often playing five sets a night.[33] While in Germany, the band recorded a single, "Boozoo Hully Gully"/"Twingy Baby", under the name Georgie and the Monarchs. This was Morrison's first recording, taking place in November 1963 at Ariola Studios in Cologne with Morrison on saxophone; it made the lower reaches of the German charts.[39][40]

Upon returning to Belfast in November 1963, the group disbanded,[41] so Morrison connected with Geordie Sproule again and played with him in the Manhattan Showband along with guitarist Herbie Armstrong. When Armstrong auditioned to play with Brian Rossi and the Golden Eagles, later known as the Wheels, Morrison went along and was hired as a blues singer.[42][43][44]

Them: 1964–1966

[edit]The roots of Them, the band that first broke Morrison on the international scene, came in April 1964 when he responded to an advert for musicians to play at a new R&B club at the Maritime Hotel in College Square North – an old Belfast hostel frequented by sailors.[45][46] The new club needed a band for its opening night. Morrison had left the Golden Eagles (the group with which he had been performing at the time), so he created a new band out of the Gamblers, an East Belfast group formed by Ronnie Millings, Billy Harrison and Alan Henderson in 1962.[47][48] Eric Wrixon, still a schoolboy, was the piano player and keyboardist.[49] Morrison played saxophone and harmonica and shared vocals with Billy Harrison. They followed Eric Wrixon's suggestion for a new name, and the Gamblers morphed into Them, their name taken from the horror movie Them![50]

The band's R&B performances at the Maritime attracted attention. Them performed without a routine and Morrison ad libbed, creating his songs live as he performed.[51] While the band did covers, they also played some of Morrison's early songs, such as "Could You Would You", which he had written in Camden Town while touring with the Manhattan Showband.[52] The debut of Morrison's "Gloria" took place on stage here. Sometimes, depending on his mood, the song could last up to twenty minutes. Morrison has said, "Them lived and died on the stage at the Maritime Hotel", believing the band did not manage to capture the spontaneity and energy of their live performances on their records.[53] The statement also reflected the instability of the Them line-up, with numerous members passing through the ranks after the definitive Maritime period. Morrison and Henderson remained the only constants, and a less successful version of Them soldiered on after Morrison's departure.[54]

Dick Rowe of Decca Records became aware of the band's performances and signed Them to a standard two-year contract. In that period, they released two albums and ten singles, with two more singles released after Morrison departed the band. They had three chart hits, "Baby, Please Don't Go" (1964), "Here Comes the Night" (1965), and "Mystic Eyes" (1965),[55] but it was the B-side of "Baby, Please Don't Go", the garage band classic "Gloria",[56] that went on to become a rock standard covered by Patti Smith, the Doors, the Shadows of Knight, Jimi Hendrix and many others.[57]

Building on the success of their singles in the United States, and riding on the back of the British Invasion, Them undertook a two-month tour of America in May and June 1966 that included a residency from 30 May to 18 June at the Whisky a Go Go in Los Angeles.[59] The Doors were the supporting act on the last week,[60] and Morrison's influence on the Doors singer Jim Morrison was noted by John Densmore in his book Riders on the Storm. Brian Hinton relates how "Jim Morrison learned quickly from his near namesake's stagecraft, his apparent recklessness, his air of subdued menace, the way he would improvise poetry to a rock beat, even his habit of crouching down by the bass drum during instrumental breaks."[61] On the final night, the two Morrisons and the two bands jammed together on "Gloria".[62][63][64]

Toward the end of the tour the band members became involved in a dispute with their manager, Decca Records' Phil Solomon, over the revenues paid to them; that, coupled with the expiry of their work visas, meant the band returned from America dejected. After two more concerts in Ireland, Them split up. Morrison concentrated on writing some of the songs that would appear on Astral Weeks, while the remnants of the band reformed in 1967 and relocated to America.[65]

Start of solo career with Bang Records and "Brown Eyed Girl": 1967

[edit]Bert Berns, Them's producer and composer of their 1965 hit "Here Comes the Night", persuaded Morrison to return to New York to record solo for his new label, Bang Records.[67] Morrison flew over and signed a contract he had not fully studied.[68] During a two-day recording session at A & R Studios starting 28 March 1967, he recorded eight songs, originally intended to be used as four singles.[69] Instead, these songs were released as the album Blowin' Your Mind! without Morrison's consultation. He said he only became aware of the album's release when a friend mentioned that he had bought a copy. Morrison was unhappy with the album and said he "had a different concept of it".[70]

"Brown Eyed Girl", one of the songs from Blowin' Your Mind!, was released as a single in mid-June 1967,[71] reaching number ten in the US charts. "Brown Eyed Girl" became Morrison's most-played song.[72] The song spent a total of sixteen weeks on the chart.[73] It is considered to be Morrison's signature song.[74] An evaluation in 2015 of downloads since 2004 and airplay since 2010 had "Brown Eyed Girl" as the most popular song of the entire 1960s decade.[75] In 2000, it was listed at No. 21 on the Rolling Stone/MTV list of 100 Greatest Pop Songs[76] and as No. 49 on VH1's list of the 100 Greatest Rock Songs.[77] In 2010, "Brown Eyed Girl" was ranked No. 110 on the Rolling Stone magazine list of 500 Greatest Songs of All Time.[78] In January 2007, "Brown Eyed Girl" was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame.[79]

Following the death of Berns in 1967, Morrison became involved in a contract dispute with Berns' widow, Ilene Berns, that prevented him from performing on stage or recording in the New York area.[80] The song "Big Time Operators", released in 1993, is thought to allude to his dealings with the New York music business during this period.[81] He moved to Boston, Massachusetts, and faced personal and financial problems; he had "slipped into a malaise" and had trouble finding concert bookings.[82] He regained his professional footing through the few gigs he could find, and started recording with Warner Bros. Records.[83][84]

Warner Bros bought out Morrison's Bang contract with a $20,000 cash transaction that took place in an abandoned warehouse on Ninth Avenue in Manhattan.[85] A clause required Morrison to submit 36 original songs within a year to Berns' music publishing company. He recorded them in one session on an out-of-tune guitar, with lyrics about subjects including ringworm and sandwiches. Ilene Berns thought the songs were "nonsense" and did not use them.[86][87] The throwaway compositions came to be known as the "revenge" songs,[88] and did not see official release until the 2017 compilation The Authorized Bang Collection.[89]

Astral Weeks: 1968

[edit]Morrison's first album for Warner Bros Records was Astral Weeks (which he had already performed in several clubs around Boston), a mystical song cycle, often considered to be his best work and one of the best albums of all time.[91][92][93] Morrison has said, "When Astral Weeks came out, I was starving, literally."[94] Released in 1968, the album originally received an indifferent response from the public, but it eventually achieved critical acclaim.

The album is described by AllMusic's William Ruhlmann as hypnotic, meditative, and as possessing a unique musical power.[92] It has been compared to French Impressionism and mystical Celtic poetry.[95][96][97] A 2004 Rolling Stone magazine review begins with the words: "This is music of such enigmatic beauty that thirty-five years after its release, Astral Weeks still defies easy, admiring description."[98] Alan Light later described Astral Weeks as "like nothing he had done previously—and really, nothing anyone had done previously. Morrison sings of lost love, death, and nostalgia for childhood in the Celtic soul that would become his signature."[12] It has been placed on many lists of best albums of all time. In the 1995 Mojo list of 100 Best Albums, it was listed as number two and was number nineteen on the Rolling Stone magazine's The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time in 2003.[99][100] In December 2009, it was voted the top Irish album of all time by a poll of leading Irish musicians conducted by Hot Press magazine.[101][102]

Moondance to Into the Music: 1970–1979

[edit]

Morrison's third solo album, Moondance, which was released in 1970, became his first million selling album and reached number twenty-nine on the Billboard charts.[103][104][105] The style of Moondance stood in contrast to that of Astral Weeks. Whereas Astral Weeks had a sorrowful and vulnerable tone, Moondance restored a more optimistic and cheerful message to his music,[106] which abandoned the previous record's abstract folk compositions in favour of more formally composed songs and a lively rhythm and blues style he expanded on throughout his career.[107]

The title track, although not released in the US as a single until 1977, received heavy play in FM radio formats.[108] "Into the Mystic" has also gained a wide following over the years.[109][110] "Come Running", which reached the American Top 40, rescued Morrison from what seemed then as Hot 100 obscurity.[111] Moondance was both well received and favourably reviewed. Lester Bangs and Greil Marcus had a combined full-page review in Rolling Stone, saying Morrison now had "the striking imagination of a consciousness that is visionary in the strongest sense of the word."[112] "That was the type of band I dig," Morrison said of the Moondance sessions. "Two horns and a rhythm section—they're the type of bands that I like best." He produced the album himself as he felt like nobody else knew what he wanted.[113] Moondance was listed at number sixty-five on the Rolling Stone magazine's The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time.[100] In March 2007, Moondance was listed as number seventy-two on the NARM Rock and Roll Hall of Fame list of the "Definitive 200".[114]

Over the next few years, he released a succession of albums, starting with a second one in 1970. His Band and the Street Choir had a freer, more relaxed sound than Moondance, but not the perfection, in the opinion of critic Jon Landau, who felt like "a few more numbers with a gravity of 'Street Choir' would have made this album as perfect as anyone could have stood."[115] It contained the hit single "Domino", which charted at number nine in the Billboard Hot 100.[116]

In 1971, he released another well-received album, Tupelo Honey.[117] This album produced the hit single "Wild Night" that was later covered by John Mellencamp and Meshell Ndegeocello. The title song has a notably country-soul feel about it[118] and the album ended with another country tune, "Moonshine Whiskey". Morrison said he originally intended to make an all-country album.[119] The recordings were as live as possible—after rehearsing the songs the musicians would enter the studio and play a whole set in one take.[120] His co-producer, Ted Templeman, described this recording process as the "scariest thing I've ever seen. When he's got something together, he wants to put it down right away with no overdubbing."[121]

Released in 1972, Saint Dominic's Preview revealed Morrison's break from the more accessible style of his previous three albums and moving back towards the more daring, adventurous, and meditative aspects of Astral Weeks. The combination of two styles of music demonstrated a versatility not previously found in his earlier albums.[122] Two songs, "Jackie Wilson Said (I'm in Heaven When You Smile)" and "Redwood Tree", reached the Hot 100 singles chart.[111] The songs "Listen to the Lion" and "Almost Independence Day" are each over ten minutes long and employ the type of poetic imagery not heard since Astral Weeks.[122][123] It was his highest-charting album in the US until his Top Ten debut on Billboard 200 in 2008.[124]

He released his next album, Hard Nose the Highway, in 1973, receiving mixed, but mostly negative, reviews. The album contained the popular song "Warm Love" but otherwise has been largely dismissed critically.[125] In a 1973 Rolling Stone review, it was described as: "psychologically complex, musically somewhat uneven and lyrically excellent."[126]

During a three-week vacation visit to Ireland in October 1973, Morrison wrote seven of the songs that made up his next album, Veedon Fleece.[127] Though it attracted scant initial attention, its critical stature grew markedly over the years—with Veedon Fleece now often considered to be one of Morrison's most impressive and poetic works.[128][129] In a 2008 Rolling Stone review, Andy Greene writes that when released in late 1974: "it was greeted by a collective shrug by the rock critical establishment" and concludes: "He's released many wonderful albums since, but he's never again hit the majestic heights of this one."[130] "You Don't Pull No Punches, but You Don't Push the River", one of the album's side closers, exemplifies the long, hypnotic, cryptic Morrison with its references to visionary poet William Blake and to the seemingly Grail-like Veedon Fleece object.[131]

Morrison took three years to release a follow-up album. After a decade without taking time off, he said in an interview, he needed to get away from music completely and ceased listening to it for several months.[132] Also suffering from writer's block, he seriously considered leaving the music business for good.[133] Speculation that an extended jam session would be released either under the title Mechanical Bliss, or Naked in the Jungle, or Stiff Upper Lip, came to nothing,[134] and Morrison's next album was A Period of Transition in 1977, a collaboration with Dr. John, who had appeared at The Last Waltz concert with Morrison in 1976. The album received a mild critical reception and marked the beginning of a very prolific period of song-making.

Into the Music: The album's last four songs, "Angelou", "And the Healing Has Begun", and "It's All in the Game/You Know What They're Writing About" are a veritable tour-de-force with Morrison summoning every vocal trick at his disposal from Angelou's climactic shouts to the sexually-charged, half-mumbled monologue in "And the Healing Has Begun" to the barely audible whisper that is the album's final sound.

--Scott Thomas Review

The following year, Morrison released Wavelength; it became at that time the fastest-selling album of his career and soon went gold.[135] The title track became a modest hit, peaking at number forty-two. Making use of 1970s synthesisers, it mimics the sounds of the shortwave radio stations he listened to in his youth.[136] The opening track, "Kingdom Hall"—the name given by Jehovah's Witnesses to their places of worship—evoked Morrison's childhood experiences of religion with his mother,[135] and foretold the religious themes that were more evident on his next album, Into the Music.[137]

Considered by AllMusic as "the definitive post-classic-era Morrison",[138] Into the Music was released in the last year of the 1970s. Songs on this album for the first time alluded to the healing power of music, which became an abiding interest of Morrison's.[139] "Bright Side of the Road" was a joyful, uplifting song that is featured on the soundtrack of the movie, Michael.[140]

Common One to Avalon Sunset: 1980–1989

[edit]With his next album, the new decade found Morrison following his muse into uncharted territory and sometimes merciless reviews.[141][142] In February 1980, Morrison and a group of musicians travelled to Super Bear, a studio in the French Alps, to record (on the site of a former abbey) what is considered to be the most controversial album in his discography; later "Morrison admitted his original concept was even more esoteric than the final product."[143][144] The album, Common One, consisted of six songs; the longest, "Summertime in England", lasted fifteen and a half minutes and ended with the words "Can you feel the silence?". NME magazine's Paul Du Noyer called the album "colossally smug and cosmically dull; an interminable, vacuous and drearily egotistical stab at spirituality: Into the muzak."[143] Greil Marcus, whose previous writings had been favourably inclined towards Morrison, critically remarked: "It's Van acting the part of the 'mystic poet' he thinks he's supposed to be."[141] Morrison insisted the album was never "meant to be a commercial album."[141] Biographer Clinton Heylin concludes: "He would not attempt anything so ambitious again. Henceforth every radical idea would be tempered by some notion of commerciality."[144] Later, critics reassessed the album more favourably with the success of "Summertime in England".[144] Lester Bangs wrote in 1982, "Van was making holy music even though he thought he was, and us rock critics had made our usual mistake of paying too much attention to the lyrics."[141]

Morrison's next album, Beautiful Vision, released in 1982, had him returning once again to the music of his Northern Irish roots.[145] Well received by the critics and public, it produced a minor UK hit single, "Cleaning Windows", that referenced one of Morrison's first jobs after leaving school.[146] Several other songs on the album, "Vanlose Stairway", "She Gives Me Religion", and the instrumental, "Scandinavia" show the presence of a new personal muse in his life: a Danish public relations agent, who would share Morrison's spiritual interests and serve as a steadying influence on him throughout most of the 1980s.[147] "Scandinavia", with Morrison on piano,[148] was nominated in the Best Rock Instrumental Performance category for the 25th Annual Grammy Awards.[149]

Much of the music Morrison released throughout the 1980s continued to focus on the themes of spirituality and faith. His 1983 album, Inarticulate Speech of the Heart, was "a move towards creating music for meditation" with synthesisers, uilleann pipes and flute sounds, and four of the tracks were instrumentals.[150] The titling of the album and the presence of the instrumentals were noted to be indicative of Morrison's long-held belief that "it's not the words one uses but the force of conviction behind those words that matters."[148] During this period of time, Morrison had studied Scientology and gave "Special Thanks" to L. Ron Hubbard on the album's credits.[151]

A Sense of Wonder, Morrison's 1985 album, pulled together the spiritual themes contained in his last four albums, which were defined in a Rolling Stone review as: "rebirth (Into the Music), deep contemplation and meditation (Common One); ecstasy and humility (Beautiful Vision); and blissful, mantra like languor (Inarticulate Speech of the Heart)."[152] The single "Tore Down a la Rimbaud" was a reference to Rimbaud and an earlier bout of writer's block that Morrison had encountered in 1974.[153] In 1985, Morrison also wrote the musical score for the movie Lamb starring Liam Neeson.[154]

Morrison's 1986 release, No Guru, No Method, No Teacher, was said to contain a "genuine holiness ... and musical freshness that needs to be set in context to understand."[155] Critical response was favourable with a Sounds reviewer calling the album "his most intriguingly involved since Astral Weeks" and "Morrison at his most mystical, magical best."[156][157] It contains the song "In the Garden" that, according to Morrison, had a "definite meditation process which is a 'form' of transcendental meditation as its basis. It's not TM".[155] He entitled the album as a rebuttal to media attempts to place him in various creeds.[158] In an interview in the Observer he told Anthony Denselow:

There have been many lies put out about me and this finally states my position. I have never joined any organisation, nor plan to. I am not affiliated to any guru, don't subscribe to any method and for those people who don't know what a guru is, I don't have a teacher either.[159]

After releasing the "No Guru" album, Morrison's music appeared less gritty and more adult contemporary with the well-received 1987 album, Poetic Champions Compose, considered to be one of his recording highlights of the 1980s.[160] The romantic ballad from this album, "Someone Like You", has been featured subsequently in the soundtracks of several movies, including 1995's French Kiss, and in 2001, both Someone Like You and Bridget Jones's Diary.[140][161]

In 1988, he released Irish Heartbeat, a collection of traditional Irish folk songs recorded with the Irish group the Chieftains, which reached number 18 in the UK album charts. The title song, "Irish Heartbeat", was originally recorded on his 1983 album Inarticulate Speech of the Heart.[162]

The 1989 album, Avalon Sunset, which featured the hit duet with Cliff Richard "Whenever God Shines His Light" and the ballad "Have I Told You Lately" (on which "earthly love transmutes into that for God" (Hinton)),[163] reached 13 on the UK album chart. Although considered to be a deeply spiritual album,[164] it also contained "Daring Night", which "deals with full, blazing sex, whatever its churchy organ and gentle lilt suggest"(Hinton).[165] Morrison's familiar themes of "God, woman, his childhood in Belfast and those enchanted moments when time stands still" were prominent in the songs.[166] He can be heard calling out the change of tempo at the end of this song, repeating the numbers "1–4" to cue the chord changes (the first and fourth chord in the key of the music). He often completed albums in two days, frequently releasing first takes.[167][168]

The Best of Van Morrison to Back on Top: 1990–1999

[edit]The early to middle 1990s were commercially successful for Morrison with three albums reaching the top five of the UK charts, sold-out concerts, and a more visible public profile; but this period also marked a decline in the critical reception to his work.[169] The decade began with the release of The Best of Van Morrison; compiled by Morrison himself, the album was focused on his hit singles, and became a multi-platinum success remaining a year and a half on the UK charts. AllMusic determined it to be "far and away the best-selling album of his career."[109][170] In 1991 he wrote and produced four songs for Tom Jones released on the Carrying A Torch album and performed a duet with Bob Dylan on BBC Arena special.[171]

The 1994 live double album A Night in San Francisco received favourable reviews as well as commercial success by reaching number eight on the UK charts.[172][173][174][175] 1995's Days Like This also had large sales—though the critical reviews were not always favourable.[176] This period also saw a number of side projects, including the live jazz performances of 1996's How Long Has This Been Going On, from the same year Tell Me Something: The Songs of Mose Allison, and 2000's The Skiffle Sessions – Live in Belfast 1998, all of which found Morrison paying tribute to his early musical influences.

In 1997, Morrison released The Healing Game. The album received mixed reviews, with the lyrics being described as "tired" and "dull",[177] though critic Greil Marcus praised the musical complexity of the album by saying: "It carries the listener into a musical home so perfect and complete he or she might have forgotten that music could call up such a place, and then populate it with people, acts, wishes, fears."[178] The following year, Morrison finally released some of his previously unissued studio recordings in a two-disc set, The Philosopher's Stone. His next release, 1999's Back on Top, achieved modest success, being his highest-charting album in the US since 1978's Wavelength.[179]

Down the Road to Keep It Simple: 2000–2009

[edit]Van Morrison continued to record and tour in the 2000s, often performing two or three times a week.[180] He formed his own independent label, Exile Productions Ltd, which enables him to maintain full production control of each album he records, which he then delivers as a finished product to the recording label that he chooses, for marketing and distribution.[181]

In 2001, nine months into a tour with Linda Gail Lewis promoting their collaboration You Win Again, Lewis left the tour, later filing claims against Morrison for unfair dismissal and sexual discrimination. Both claims were later withdrawn, and Morrison's solicitor said, "(Mr Morrison's) pleased that these claims have finally been withdrawn. He accepted a full apology and comprehensive retraction which represents a complete vindication of his stance from the outset. Miss Lewis has given a full and categorical apology and retraction to Mr Morrison." Lewis' legal representative Christine Thompson said both parties had agreed to the terms of the settlement.[182]

The album Down the Road, released in May 2002, received a good critical reception and proved to be his highest-charting album in the US since 1972's Saint Dominic's Preview.[124] It had a nostalgic tone, with its fifteen tracks representing the various musical genres Morrison had previously covered—including R&B, blues, country and folk;[183] one of the tracks was written as a tribute to his late father George, who had played a pivotal role in nurturing his early musical tastes.[19]

Morrison's 2005 album, Magic Time, debuted at number twenty-five on the US Billboard 200 charts upon its May release, some forty years after Morrison first entered the public's eye as the frontman of Them. Rolling Stone listed it as number seventeen on The Top 50 Records of 2005.[184] Also in July 2005, Morrison was named by Amazon as one of their top twenty-five all-time best-selling artists and inducted into the Amazon.com Hall of Fame.[185] Later in the year, Morrison also donated a previously unreleased studio track to a charity album, Hurricane Relief: Come Together Now, which raised money for relief efforts intended for Gulf Coast victims devastated by hurricanes Katrina and Rita.[186] Morrison composed the song, "Blue and Green", featuring Foggy Lyttle on guitar. This song was released in 2007 on the album, The Best of Van Morrison Volume 3 and also as a single in the UK. Van Morrison was a headline act at the international Celtic music festival, The Hebridean Celtic Festival in Stornoway, Outer Hebrides in the summer of 2005.[187]

He released an album with a country music theme, entitled Pay the Devil, on 7 March 2006 and appeared at the Ryman Auditorium, where the tickets sold out immediately after they went on sale.[188] Pay the Devil debuted at number twenty-six on the Billboard 200 and peaked at number seven on Top Country Albums.[189][190] Amazon Best of 2006 Editor's Picks in Country listed the country album at number ten in December 2006. Still promoting the country album, Morrison's performance as the headline act on the first night of the Austin City Limits Music Festival on 15 September 2006 was reviewed by Rolling Stone magazine as one of the top ten shows of the 2006 festival.[191] In November 2006, a limited edition album, Live at Austin City Limits Festival, was issued by Exile Productions, Ltd. A later deluxe CD/DVD release of Pay the Devil, in the summer of 2006, contained tracks from the Ryman performance.[192] In October 2006, Morrison had released his first commercial DVD, Live at Montreux 1980/1974, with concerts taken from two separate appearances at the Montreux Jazz Festival.

A new double CD compilation album, The Best of Van Morrison Volume 3, was released in June 2007 containing thirty-one tracks, some of which were previously unreleased. Morrison selected the tracks, which ranged from the 1993 album Too Long in Exile to the song "Stranded" from the 2005 album Magic Time.[193] On 3 September 2007, Morrison's complete catalogue of albums from 1971 through 2002 were made available exclusively at the iTunes Store in Europe and Australia and during the first week of October 2007, the albums became available at the US iTunes Store.[194]

Still on Top – The Greatest Hits, a thirty-seven-track double CD compilation album, was released on 22 October 2007 in the UK on the Polydor label. On 29 October 2007, the album charted at number two on the Official UK Top 75 Albums—his highest UK charting.[195] The November release in the US and Canada contains twenty-one selected tracks.[196] The hits released on albums with the copyrights owned by Morrison as Exile Productions Ltd.—1971 and later—had been remastered in 2007.

Keep It Simple, Morrison's 33rd studio album of completely new material, was released by Exile/Polydor Records on 17 March 2008 in the UK and released by Exile/Lost Highway Records in the US and Canada on 1 April 2008.[197] It comprised eleven self-penned tracks. Morrison promoted the album with a short US tour including an appearance at the SXSW music conference,[198][199] and a UK concert broadcast on BBC Radio 2. In the first week of release Keep It Simple debuted on the Billboard 200 chart at number ten, Morrison's first Top Ten charting in the US.[200]

Born to Sing to Three Chords: 2010–2020

[edit]Morrison released two albums in the first half of the decade, followed by a further six in just five years, his productivity increasing noticeably as he turned 70. Born to Sing: No Plan B was released on 2 October 2012 on Blue Note Records. The album was recorded in Belfast, Morrison's birthplace and hometown.[201] The first single from this album, "Open the Door (To Your Heart)", was released on 24 August 2012.[202] A selection of Morrison's lyrics, Lit Up Inside, was published by City Lights Books in the US and Faber & Faber in the UK.[203] The book was released on 2 October 2014 and an evening of words and music commenced at the Lyric Theatre, London on 17 November 2014 to mark its launch. Morrison himself selected his best and most iconic lyrics from a catalog of 50 years of writing.[204]

In 2015, Morrison sold the rights to most of his catalogue to Legacy Recordings, the catalog division of Sony Music. This resulted in 33 of his albums being made available as digital releases and through all streaming services for the first time that August.[205] His first album recorded with Sony under the new contract was Duets: Re-working the Catalogue, released on 24 March 2015 on the subsidiary, RCA Records.[206] Morrison's 70th birthday in 2015 was marked by celebrations in his hometown of Belfast, commencing with BBC Radio Ulster presenting programs including "Top 70 Van Tracks" between 26 and 28 August. As the headline act ending the Eastside Arts Festival, Morrison performed two 70th-birthday concerts on Cyprus Avenue on his birthday 31 August. The first of the concerts was broadcast live on BBC Radio Ulster and a 60-minute BBC film of highlights from the concerts, entitled Up On Cyprus Avenue, was first shown on 4 September.[207][208][209][210] The following year, on 30 September, Morrison released Keep Me Singing, his 36th studio album. "Too Late", the first single, was released on the same day. The songs are twelve originals and one cover and the album represents his first release of originals since Born to Sing: No Plan B in 2012. A short tour of the U.S. followed with six dates in October 2016,[211] followed by a short tour of the U.K. with eight dates in October—December 2016, including a London show at The O2 Arena on 30 October. The U.S. tour resumed in January 2017 with five new dates in Las Vegas and Clearwater, Florida.[212]

Morrison's album Roll with the Punches was released on 22 September 2017. That July, he and Universal Music Group were sued by former professional wrestler Billy Two Rivers for using his likeness on its cover and promotional material without his permission. On 4 August, Two Rivers' lawyer said the parties had reached a preliminary agreement to settle the matter out of court.[213] He released his 38th studio album, Versatile, on 1 December 2017. It features covers of nine classic jazz standards and seven original songs including his arrangement of the traditional "Skye Boat Song".[214] He quickly followed up with his 39th studio album, You're Driving Me Crazy, released on 27 April 2018 via Sony Legacy Recordings. The album features a collaboration with Joey DeFrancesco on a mixture of blues and jazz classics that include eight Morrison originals from his back catalogue.[215]

In October 2018, Morrison announced that his 40th studio album, The Prophet Speaks, would be released by Caroline International on 7 December 2018.[216] A year later, in November 2019, he released his 41st studio album, Three Chords & the Truth. On 5 March 2020 Faber and Faber published Keep 'Er Lit, the second volume of Van Morrison's selected lyrics.[217] It features a foreword of fellow poet Paul Muldoon and comprehends 120 songs from across his career.[218] In November 2020 Morrison and Eric Clapton collaborated on a single called "Stand and Deliver", whose profits from sales will be donated to Morrison's Lockdown Financial Hardship Fund.[219]

Coronavirus controversy

[edit]During the COVID-19 pandemic, Morrison made numerous statements against social distancing measures that affected live music events, and made calls to "fight pseudo-science".[220] Continuing with this narrative, Morrison released three new songs in September 2020, which had messages of protest against COVID-19 lockdowns in the UK. Morrison accused the UK government of "taking our freedom".[221] He had performed socially distanced concerts previously, but said that the shows were not a sign of "compliance".[222]

There were calls in Belfast for Belfast City Council to revoke his Freedom of the City honour following the statements: city councillor Emmet McDonough-Brown said that his lyrics were "undermining the guidance in place to protect lives and are ignorant of established science as we grapple with Covid-19."[223] Northern Ireland health minister Robin Swann accused Morrison of smearing public health practitioners[224] and called Morrison's anti-lockdown songs "dangerous".[221] In November 2021, Swann sued Morrison for defamation, after he said that Swann was a "fraud" and "very dangerous".[225][226] In 2022, Morrison issued legal proceedings against Swann over an opinion piece in Rolling Stone magazine that was critical of Morrison's anti-lockdown songs and actions.[227] Both legal claims were settled confidentially shortly before their respective court proceedings were to begin in September 2024.[228]

2020s

[edit]In March 2021, Morrison announced that his 42nd album, Latest Record Project, Volume 1, would be released by Exile Productions and BMG on 7 May. The 28-track album includes songs such as "Why Are You on Facebook?", "They Own The Media" and "Western Man". In addition to digitally, it was released as a 2-CD set and on triple vinyl.[229][230][231] The album marked a return to the UK Top Ten for Morrison, making the 2020s the fourth consecutive decade in which he has achieved such success.[232]

The following year, What's It Gonna Take? explored many of the same themes, but was less successful commercially.[233] In 2023, he returned to his roots with Moving on Skiffle and Accentuate the Positive.[234]

Van Morrison's songs were used extensively in Kenneth Branagh's Oscar-winning 2021 film Belfast:[235] Morrison received his first nomination for the Academy Award for Best Original Song for "Down to Joy".[236] Several tracks were also featured in Cherry, released the same year.

Live performances

[edit]1970s

[edit]

By 1972, after being a performer for nearly ten years, Morrison began experiencing stage fright when performing for audiences of thousands, as opposed to the hundreds he had experienced in his early career. He became anxious on stage and had difficulty establishing eye contact with the audience. He once said in an interview about performing on stage, "I dig singing the songs but there are times when it's pretty agonising for me to be out there." After a brief break from music, he started appearing in clubs, regaining his ability to perform live, albeit with smaller audiences.[33]

The 1974 live double album It's Too Late to Stop Now has been called one of the greatest recordings of a live concert[237][238][239] and has appeared on lists of greatest live albums of all time.[240][241][242][243] Biographer Johnny Rogan wrote, "Morrison was in the midst of what was arguably his greatest phase as a performer."[244] Performances on the album were from tapes made during a three-month tour of the US and Europe in 1973 with the backing group the Caledonia Soul Orchestra. Soon after recording the album, Morrison restructured the Caledonia Soul Orchestra into a smaller unit, the Caledonia Soul Express.[245]

On Thanksgiving Day 1976, Morrison performed at the farewell concert for the Band. It was his first live performance in several years, and he considered skipping his appearance until the last minute, even refusing to go on stage when they announced his name. His manager, Harvey Goldsmith, said he "literally kicked him out there."[246][247] Morrison was on good terms with the members of the Band as near-neighbours in Woodstock, and they had the shared experience of stage fright. At the concert, he performed two songs. His first was a rendition of the classic Irish song "Too Ra Loo Ra Loo Ral".[248] His second song was "Caravan", from his 1970 album Moondance. Greil Marcus, in attendance at the concert, wrote: "Van Morrison turned the show around ... singing to the rafters and ... burning holes in the floor. It was a triumph, and as the song ended Van began to kick his leg into the air out of sheer exuberance and he kicked his way right offstage like a Rockette. The crowd had given him a fine welcome and they cheered wildly when he left."[249] The filmed concert served as the basis for Martin Scorsese's 1978 film, The Last Waltz.[250]

During his association with the Band, Morrison acquired the nicknames "Belfast Cowboy" and "Van the Man".[251] On the Band's album Cahoots, as part of the duet "4% Pantomime" that Morrison sings with Richard Manuel (and that he co-wrote with Robbie Robertson), Manuel addresses him, "Oh, Belfast Cowboy". When he leaves the stage after performing "Caravan" on The Last Waltz, Robertson calls out "Van the Man!"[137]

1990s

[edit]On 21 July 1990, Morrison joined many other guests for Roger Waters' massive performance of The Wall – Live in Berlin. He sang "Comfortably Numb" with Roger Waters and several members from The Band: Levon Helm, Garth Hudson and Rick Danko. At the concert's end, he and the other performers sang "The Tide Is Turning". The live audience was estimated at between three hundred thousand and half a million people, and it was broadcast live on television as well.[252]

Morrison performed before an estimated audience of sixty to eighty thousand people when US President Bill Clinton visited Belfast, Northern Ireland on 30 November 1995. His song "Days Like This" had become the official anthem for the Northern Irish peace movement.[253]

2000s and live albums

[edit]Van Morrison continued performing concerts throughout the year, rather than touring.[180] Playing few of his best-known songs in concert, he has firmly resisted relegation to a nostalgia act.[254][255] During a 2006 interview, he told Paul Sexton:

I don't really tour. This is another misconception. I stopped touring in the true sense of the word in the late 1970s, early 1980s, possibly. I just do gigs now. I average two gigs a week. Only in America do I do more, because you can't really do a couple of gigs there, so I do more, 10 gigs or something there.[256]

On 7 and 8 November 2008, at the Hollywood Bowl in Los Angeles, California, Morrison performed the entire Astral Weeks album live for the first time. The Astral Weeks band featured guitarist Jay Berliner, who had played on the album that was released forty years previously in November 1968. Also featured on piano was Roger Kellaway. A live album entitled Astral Weeks Live at the Hollywood Bowl resulted from these two performances.[258] The new live album on CD was released on 24 February 2009,[259] followed by a DVD from the performances.[260] The DVD, Astral Weeks Live at the Hollywood Bowl: The Concert Film was released via Amazon Exclusive on 19 May 2009.

In February and March 2009, Morrison returned to the US for Astral Weeks Live concerts, interviews and TV appearances with concerts at Madison Square Garden and at the Beacon Theatre in New York City.[261][262] He was interviewed by Don Imus on his Imus in the Morning radio show and put in guest appearances on Late Night with Jimmy Fallon and Live with Regis and Kelly.[263][264][265] Morrison continued with the Astral Weeks performances with two concerts at the Royal Albert Hall in London in April[266][267] and then returned to California in May 2009 performing the Astral Weeks songs at the Hearst Greek Theatre in Berkeley, the Orpheum Theatre in Los Angeles, California and appeared on The Tonight Show with Jay Leno.[268] Morrison filmed the concerts at the Orpheum Theatre so they could be viewed by Farrah Fawcett, confined to bed with cancer and thus unable to attend the concerts.[269][270]

In addition to It's Too Late to Stop Now and Astral Weeks Live at the Hollywood Bowl, Morrison has released three other live albums: Live at the Grand Opera House Belfast in 1984; A Night in San Francisco in 1994 that Rolling Stone magazine felt stood out as: "the culmination of a career's worth of soul searching that finds Morrison's eyes turned toward heaven and his feet planted firmly on the ground";[172] and The Skiffle Sessions – Live in Belfast 1998 recorded with Lonnie Donegan and Chris Barber and released in 2000.

Morrison was scheduled to perform at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame's 25th anniversary concert on 30 October 2009, but cancelled.[271] In an interview on 26 October, Morrison told his host, Don Imus, he had planned to play "a couple of songs" with Eric Clapton (who had cancelled on 22 October due to gallstone surgery),[272] and they would do something else together at "some other stage of the game".[273]

2010s to present

[edit]Morrison performed for the Edmonton Folk Music Festival in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada on 4 August 2010 as the headline act for the fundraiser and was scheduled as second-day headliner at the Feis 2011 Festival in London's Finsbury Park on 19 June 2011.[274][275][276] He appeared in concert at Odyssey Arena in Belfast on 3 February and at the O2 in Dublin on 4 February 2012. He appeared at the 46th Montreux Jazz Festival as a headliner on 7 July 2012.[277]

In 2014, Morrison's former high school Orangefield High School, formerly known as Orangefield Boys' Secondary School closed its doors permanently. To mark the school's closure Morrison performed in the school assembly hall for three nights of concerts from 22 to 24 August. The performance on 22 August was exclusively for former teachers and pupils and the two remaining concerts were for members of the public[278] The first night of the Nocturne Live[279] concerts at Blenheim Palace, Oxfordshire, UK on 25 June 2015, featured Morrison and Grammy Award-winning American Jazz vocalist and songwriter Gregory Porter.

In June 2021, The Times noted that "fittingly for someone who has been so vocally opposed to the lockdown" resulting from the 2020–2021 coronavirus pandemic, "Van Morrison played one of the first big-scale concerts in London since events, albeit tentatively, started up again." Will Hodgkinson wrote that the show "was as good an argument for the return of live music as you could wish for."[280]

Collaborations

[edit]Van Morrison has collaborated extensively with a variety of artists throughout his career.[281] He has worked with many legends in soul and blues, including John Lee Hooker, Ray Charles, George Benson, Eric Clapton, Bobby Womack, and BB King, along with The Chieftains, Gregory Porter, Michael Bublé, Joss Stone, Natalie Cole and Mark Knopfler.[282]

1980s

[edit]Morrison and the internationally renowned Irish folk band The Chieftains recorded the album Irish Heartbeat (1988). Consisting of Irish folk songs, it entered the UK Top 20. "Whenever God Shines His Light", on Avalon Sunset (1989), is a duet with Cliff Richard, which charted at No. 20 on the UK Singles Chart and No. 3 on the Irish Singles Chart.[283][284][285] AllMusic critic Jason Ankeny found it to be a "standout opener" on the album.[286] For critic Patrick Humphries, it was "the most manifest example of Morrison's Christian commitment," and while "not one of Morrison's most outstanding songs" it works as "a testament of faith".[287]

1990s

[edit]The decade saw an upsurge in Van Morrison's collaborations. He developed a close association with two vocal talents at opposite ends of their careers: Georgie Fame (with whom Morrison had already worked occasionally) lent his voice and Hammond organ skills to Morrison's band; and Brian Kennedy's vocals complemented the grizzled voice of Morrison, both in studio and live performances. He reunited with The Chieftains on their 1995 album, The Long Black Veil, with a reworking of Morrison's song "Have I Told You Lately" winning the Grammy Award for Best Pop Collaboration with Vocals.[288] He produced, and was featured on, several tracks with blues legend John Lee Hooker on Hooker's 1997 album, Don't Look Back. This album won a Grammy Award for Best Traditional Blues Album in 1998, and the title track "Don't Look Back", a duet with Morrison, took the Grammy for Best Pop Collaboration with Vocals.[289] The project capped a series of Morrison and Hooker collaborations that began in 1971 when they performed a duet on the title track of Hooker's 1972 album Never Get Out of These Blues Alive. On this album, Hooker also recorded a cover of Morrison's "T.B. Sheets".[290] Morrison collaborated with Tom Jones on his 1999 album Reload, when the pair sang on Morrison's song, "Sometimes We Cry".

2000s to present

[edit]Morrison delivered vocals on "The Last Laugh" on Mark Knopfler's Sailing to Philadelphia (2000), and that year also recorded a classic country music duet album, You Win Again with Linda Gail Lewis.[291] The album received a three-star review from AllMusic, who called it "a roots effort that never sounds studied".[292] In 2004, Morrison was one of the guests on Ray Charles' album Genius Loves Company. The pair performed Morrison's "Crazy Love". In 2015 he recorded an album of collaborations, Duets: Re-working the Catalogue, which featured, among others, Steve Winwood, Taj Mahal, Mavis Staples, Mick Hucknall, and Morrison's daughter Shana Morrison. Morrison also developed a partnership with Joey DeFrancesco, with the pair collaborating on a number of albums. During the COVID pandemic Morrison recorded tracks with Eric Clapton criticizing 'harm-reduction' measures.[293]

Artistry

[edit]Vocals

[edit]It is at the heart of Morrison's presence as a singer that when he lights on certain sounds, certain small moments inside a song—hesitations, silences, shifts in pressure, sudden entrances, slamming doors—can then suggest whole territories, completed stories, indistinct ceremonies, far outside anything that can be literally traced in the compositions that carry them.

Featuring his characteristic growl—a mix of folk, blues, soul, jazz, gospel, and Ulster Scots Celtic influences—Morrison is widely considered by many rock historians to be one of the most unusual and influential vocalists in the history of rock and roll.[295][296][297][298][299] Critic Greil Marcus has said "no white man sings like Van Morrison."[300] In his 2010 book, Marcus wrote, "As a physical fact, Morrison may have the richest and most expressive voice pop music has produced since Elvis Presley, and with a sense of himself as an artist that Elvis was always denied."[301]

As Morrison began live performances of the 40-year-old album Astral Weeks in 2008, there were comparisons to his youthful voice of 1968. His early voice was described as "flinty and tender, beseeching and plaintive".[90] Forty years later, the difference in his vocal range and power were noticeable but reviewers and critic's comments were favourable: "Morrison's voice has expanded to fill his frame; a deeper, louder roar than the blue-eyed soul voice of his youth—softer on the diction—but none the less impressively powerful."[257] Morrison also commented on the changes in his approach to singing: "The approach now is to sing from lower down [the diaphragm] so I do not ruin my voice. Before, I sang in the upper area of my throat, which tends to wreck the vocal cords over time. Singing from lower in the belly allows my resonance to carry far. I can stand four feet from a mic and be heard quite resonantly."[302]

Songwriting and lyrics

[edit]Morrison has written hundreds of songs[303][304] during his career with a recurring theme reflecting a nostalgic yearning for the carefree days of his childhood in Belfast.[305] Some of his song titles derive from familiar locations in his childhood, such as "Cyprus Avenue" (a nearby street), "Orangefield" (the boys' school he attended), and "On Hyndford Street" (where he was born). Also frequently present in Morrison's best love songs is a blending of the sacred-profane as evidenced in "Into the Mystic" and "So Quiet in Here".[306][307]

Beginning with his 1979 album, Into the Music, and the song "And the Healing Has Begun", a frequent theme of his music and lyrics has been based on his belief in the healing power of music combined with a form of mystic Christianity. This theme has become one of the predominant qualities of his work.[308]

His lyrics show the influence of the visionary poets William Blake and W. B. Yeats[309] and others such as Samuel Taylor Coleridge and William Wordsworth.[310] Biographer Brian Hinton believes "like any great poet from Blake to Seamus Heaney he takes words back to their origins in magic ... Indeed, Morrison is returning poetry to its earliest roots—as in Homer or Old English epics like Beowulf or the Psalms or folk song—in all of which words and music combine to form a new reality."[306] Another biographer, John Collis, believes Morrison's style of jazz singing and repeating phrases preclude his lyrics from being regarded as poetry or as Collis asserts: "he is more likely to repeat a phrase like a mantra, or burst into scat singing. The words may often be prosaic, and so can hardly be poetry."[311]

Morrison has described his songwriting method by remarking: "I write from a different place. I do not even know what it is called or if it has a name. It just comes and I sculpt it, but it is also a lot of hard work doing the sculpting."[302]

Performance style

[edit]Van Morrison is interested, obsessed with how much musical or verbal information he can compress into a small space, and, almost, conversely, how far he can spread one note, word, sound, or picture. To capture one moment, be it a caress or a twitch. He repeats certain phrases to extremes that from anybody else would seem ridiculous, because he's waiting for a vision to unfold, trying as unobtrusively as possible to nudge it along ... It's the great search, fuelled by the belief that through these musical and mental processes illumination is attainable. Or may at least be glimpsed.

Critic Greil Marcus argues that, given the truly distinctive breadth and complexity of Morrison's work, it is almost impossible to cast his work among that of others: "Morrison remains a singer who can be compared to no other in the history of rock & roll, a singer who cannot be pinned down, dismissed, or fitted into anyone's expectations."[313] Or in the words of Jay Cocks: "He extends himself only to express himself. Alone among rock's great figures—and even in that company he is one of the greatest—Morrison is adamantly inward. And unique. Although he freely crosses musical boundaries— R&B, Celtic melodies, jazz, rave-up rock, hymns, down-and-dirty blues—he can unfailingly be found in the same strange place: on his own wavelength."[314]

His spiritually themed style of music first came into full expression with Astral Weeks in 1968 and he was noted to have remained a "master of his transcendental craft" in 2009 while performing the Astral Weeks songs live.[315][316][317][318] This musical art form was based on stream of consciousness songwriting and emotional vocalising of lyrics that have no basis in normal structure or symmetry. His live performances are dependent on building dynamics with spontaneity between himself and his band, whom he controls with hand gestures throughout, sometimes signalling impromptu solos from a selected band member. The music and vocals build towards a hypnotic and trance-like state that depends on in-the-moment creativity. Scott Foundas with LA Weekly wrote "he seeks to transcend the apparent boundaries of any given song; to achieve a total freedom of form; to take himself, his band and the audience on a journey whose destination is anything but known."[305][319] Greil Marcus wrote an entire book devoted to examining the moments in Morrison's music where he reaches this state of transcendence and explains: "But in his music the same sense of escape from ordinary limits—a reach for, or the achievement of, a kind of violent transcendence—can come from hesitations, repetitions of words or phrases, pauses, the way a musical change by another musician is turned by Morrison as a bandleader or seized on by him as a singer and changed into a sound that becomes an event in and of itself. In these moments, the self is left behind, and the sound, that "yarragh," becomes the active agent: a musical person, with its own mind, its own body."[320] A book reviewer further described it as "This transcendent moment of music when the song and the singer are one thing not two, neither dependent on the other or separate from the other but melded to the other like one, like breath and life ..."[321]

Morrison has said he believes in the jazz improvisational technique of never performing a song the same way twice and except for the unique rendition of the Astral Weeks songs live, doesn't perform a concert from a preconceived set list.[254] Morrison has said he prefers to perform at smaller venues or symphony halls noted for their good acoustics.[322] His ban against alcoholic beverages, which made entertainment news during 2008, was an attempt to prevent the disruptive and distracting movement of audience members leaving their seats during the performances.[323] In a 2009 interview, Morrison stated: "I do not consciously aim to take the listener anywhere. If anything, I aim to take myself there in my music. If the listener catches the wavelength of what I am saying or singing, or gets whatever point whatever line means to them, then I guess as a writer I may have done a day's work."[324]

Genre

[edit]The music of Van Morrison has encompassed many genres since his early days as a blues and R&B singer in Belfast. Over the years he has recorded songs from a varying list of genres drawn from many influences and interests. As well as blues and R&B, his compositions and covers have moved between pop music, jazz, rock, folk, country, gospel, Irish folk and traditional, big band, skiffle, rock and roll, new age, classical and sometimes spoken word ("Coney Island") and instrumentals.[325] Morrison defines himself as a soul singer.[326]

Morrison's music has been described by music journalist Alan Light as "Celtic soul",[12] or what biographer Brian Hinton referred to as a new alchemy called "Caledonian soul."[306] Another biographer, Ritchie Yorke quoted Morrison as believing that he has "the spirit of Caledonia in his soul and his music reflects it."[327] According to Yorke, Morrison claimed to have discovered "a certain quality of soul" when he first visited Scotland (his Belfast ancestors were of Ulster Scots descent) and Morrison has said he believes there is some connection between soul music and Caledonia. Yorke said Morrison "discovered several years after he first began composing music that some of his songs lent themselves to a unique major modal scale (without sevenths) which of course is the same scale as that used by bagpipe players and old Irish and Scottish folk music."[327]

'Caledonia' theme

[edit]The name "Caledonia" has played a prominent role in Morrison's life and career. Biographer Ritchie Yorke had pointed out already by 1975 that Morrison has referred to Caledonia so many times in his career that he "seems to be obsessed with the word".[327] In his 2009 biography, Erik Hage found "Morrison seemed deeply interested in his paternal Scottish roots during his early career, and later in the ancient countryside of England, hence his repeated use of the term Caledonia (an ancient Roman name for Scotland/northern Britain)".[328] As well as being his daughter Shana's middle name, it is the name of his first production company, his studio, his publishing company, two of his backing groups, his parents' record store in Fairfax, California in the 1970s, and he also recorded a cover of the song "Caldonia" (with the name spelt "Caledonia") in 1974.[327][329] Morrison used "Caledonia" in what has been called a quintessential Van Morrison moment in the song, "Listen to the Lion" with the lyrics, "And we sail, and we sail, way up to Caledonia".[330] Morrison used "Caledonia" as a mantra in the live performance of the song "Astral Weeks" recorded at the two Hollywood Bowl concerts.[324] As late as 2016's Keep Me Singing album, he recorded a self-penned instrumental entitled "Caledonia Swing."

Influence

[edit]Morrison's influence can readily be heard in the music of a diverse array of major artists. According to The Rolling Stone Encyclopedia of Rock and Roll (Simon & Schuster, 2001), "his influence among rock singers/song writers is unrivaled by any living artist outside of that other prickly legend, Bob Dylan. Echoes of Morrison's rugged literateness and his gruff, feverish emotive vocals can be heard in latter day icons ranging from Bruce Springsteen to Elvis Costello".[297] He has influenced an array of top tier performers, including U2, with Bono recalling, "I am in awe of a musician like Van Morrison. I had to stop listening to Van Morrison records about six months before we made The Unforgettable Fire because I didn't want his very original soul voice to overpower my own".[331] He has inspired John Mellencamp ("Wild Night");[332] Jim Morrison;[61] Joan Armatrading (the only musical influence she will acknowledge);[333] Nick Cave;[334] Rod Stewart;[335] Tom Petty;[336] Rickie Lee Jones (recognises both Laura Nyro and Van Morrison as the main influences on her career);[337][338] Elton John;[339] Graham Parker;[340] Sinéad O'Connor;[341] Phil Lynott of Thin Lizzy;[342] Bob Seger ("I know Bruce Springsteen was very much affected by Van Morrison, and so was I")[340] Kevin Rowland of Dexys Midnight Runners ("Jackie Wilson Said");[343][344] Jimi Hendrix ("Gloria");[345] Jeff Buckley ("The Way Young Lovers Do", "Sweet Thing");[346] Nick Drake;[347] and numerous others, including Counting Crows (their "sha-la-la" sequence in Mr Jones is a tribute to Morrison).[348] Morrison's influence reaches into the country music genre, with Hal Ketchum acknowledging, "He (Van Morrison) was a major influence in my life."[349] Ray Manzarek of the Doors described Van Morrison as "our [the Doors] favourite singer".[350]

Morrison has typically been supportive of other artists, often willingly sharing the stage with them during his concerts. On the live album A Night in San Francisco, he had as his special guests, among others, his childhood idols: Jimmy Witherspoon, John Lee Hooker and Junior Wells.[172] Although he often expresses his displeasure (in interviews and songs) with the music industry and the media in general, he has been instrumental in promoting the careers of many other musicians and singers, such as James Hunter,[351] and fellow Belfast-born brothers Brian and Bap Kennedy.[352][353] He has also influenced the visual arts: the German painter Johannes Heisig created a series of lithographs illustrating the book In the Garden – for Van Morrison, published by Städtische Galerie Sonneberg, Germany, in 1997.[354]

Next generation

[edit]Morrison's influence on a younger generation of singer-songwriters is pervasive. The list of such singer-songwriters influenced by Morrison includes Irish singer Damien Rice, who has been described as on his way to becoming the "natural heir to Van Morrison";[355] Ray Lamontagne;[356] James Morrison;[357][358] Paolo Nutini;[359] Eric Lindell[360] David Gray and Ed Sheeran[361] are also several of the younger artists influenced by Morrison. Glen Hansard of the Irish rock band the Frames (who lists Van Morrison as being part of his holy trinity with Bob Dylan and Leonard Cohen) commonly covers his songs in concert.[362] American rock band the Wallflowers have covered "Into the Mystic".[363] Canadian blues-rock singer Colin James also covers the song frequently at his concerts.[364] Actor and musician Robert Pattinson has said Van Morrison was his "influence for doing music in the first place".[365] Morrison has shared the stage with Northern Irish singer-songwriter Duke Special, who admits Morrison has been a big influence.[366]

Recognition and legacy

[edit]Morrison has received several major music awards in his career, including two Grammy Awards, with five additional nominations (1982–2004);[3] inductions into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame (January 1993), the Songwriters Hall of Fame (June 2003), and the Irish Music Hall of Fame (September 1999); and a Brit Award (February 1994). In addition, he has received civil awards: an OBE (June 1996) and an Officier de l'Ordre des Arts et des Lettres (1996). He has honorary doctorates from the University of Ulster (1992) and from Queen's University Belfast (July 2001).

Halls of Fame

[edit]The Hall of Fame inductions began in 1993 with the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Morrison was the first living inductee not to attend his own ceremony,[367][368] – Robbie Robertson from the Band accepted the award on his behalf.[369] When Morrison became the initial musician inducted into the Irish Music Hall of Fame, Bob Geldof presented Morrison with the award.[370] Morrison's third induction was into the Songwriters Hall of Fame for "recognition of his unique position as one of the most important songwriters of the past century". Ray Charles presented the award, following a performance during which the pair performed Morrison's "Crazy Love" from the album Moondance.[371] Morrison's BRIT Award was for his Outstanding Contribution to British Music.[372] Former Beirut hostage John McCarthy presented the award; while testifying to the importance of Morrison's song "Wonderful Remark.” McCarthy called it "a song ... which was very important to us."[373]

Three of Morrison's songs appear in The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame's 500 Songs that Shaped Rock and Roll: "Brown Eyed Girl", "Madame George" and "Moondance".[374] The Songwriter's Hall of Fame awarded Morrison the Johnny Mercer Award on 18 June 2015 at their 46th Annual Induction and Awards Dinner in New York City.[375]

Civil awards and honours

[edit]Morrison received two civil awards in 1996: he was appointed Officer of the Order of the British Empire for services to music,[376] and was also recognized with an award from the French government which made him an Officier de l'Ordre des Arts et des Lettres.[377] Along with these state awards he has two honorary degrees in music: an honorary doctorate in literature from the University of Ulster,[378] and an honorary doctorate in music from Queen's University in his hometown of Belfast.[379]

In 2013, Morrison was awarded the Freedom of Belfast, the highest honour the city can bestow.[380] On 15 November 2013, Morrison became the 79th recipient of the award, presented at the Waterfront Hall for his career achievements. After receiving the award, he performed a free concert for residents who won tickets from a lottery system.[381]

In August 2014, a "Van Morrison Trail" was established in East Belfast by Morrison in partnership with the Connswater Community Greenway. It is a self-guided trail, which over the course of 3.5 kilometres (2.2 mi) leads to eight places that were important to Morrison and inspirational to his music.[382]

Morrison was made a Knight Bachelor in the Queen's Birthday Honours List in 2015 for services to the music industry and to tourism in Northern Ireland.[383][384][385][386] The ceremony was performed by Prince Charles.

Industry recognition

[edit]Other awards include an Ivor Novello Award for Lifetime Achievement in 1995,[387] the BMI ICON award in October 2004 for Morrison's "enduring influence on generations of music makers",[388] and an Oscar Wilde: Honouring Irish Writing in Film award in 2007 for his contribution to over fifty films, presented by Al Pacino, who compared Morrison to Oscar Wilde – both "visionaries who push boundaries".[389] He was voted the Best International Male Singer of 2007 at the inaugural International Awards in Ronnie Scott's Jazz Club, London.[390]

In 2010, Morrison was given a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.[391] On 2 September 2014, Morrison was presented with the Legend award at the GQ Men of the Year ceremony at Royal Opera House in London.[392] On 13 October 2014, Morrison received his fifth BMI Million-Air Award for 11 million radio plays of the song "Brown Eyed Girl", making it one of the Top 10 Songs of all time on US radio and television. Morrison has also received Million-Air awards for "Have I Told You Lately".[393] In 2017, the Americana Music Association gave Van Morrison the Lifetime Achievement Award for Songwriting.[394]

Morrison was chosen to be honoured by Michael Dorf at his annual charity concert at Carnegie Hall.[395] The Music of Van Morrison was performed on 21 March 2019 by twenty musical acts including Glen Hansard, Patti Smith and Bettye LaVette.[396] In 2019, Morrison received the Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement presented by Jimmy Page during the International Achievement Summit in New York City.[397][398]

In 2022, Morrison and his song "Down to Joy" for "Belfast" were nominated for the Academy Award for Best Original Song at the 94th Academy Awards.

Lists

[edit]Morrison has also appeared in a number of "Greatest" lists, including the TIME magazine list of The All-Time 100 Albums,[399] which contained Astral Weeks and Moondance, and he appeared at number thirteen on the list of WXPN's 885 All Time Greatest Artists.[400] In 2000, Morrison ranked twenty-fifth on American cable music channel VH1's list of its "100 Greatest Artists of Rock and Roll".[401] In 2004, Rolling Stone magazine ranked Van Morrison forty-second on their list of "100 Greatest Artists of All Time".[402]

Paste ranked him twentieth in their list of "100 Greatest Living Songwriters" in 2006.[403] Q ranked him twenty-second on their list of "100 Greatest Singers" in April 2007[404] and he was voted twenty-fourth on the November 2008 list of Rolling Stone magazine's 100 Greatest Singers of All Time.[405]

Tribute albums

[edit]- No Prima Donna: The Songs of Van Morrison (1994)

- The Van Morrison Songbook (1997)[406]

- Into the Mystic: An Instrumental Tribute to Van Morrison (2000)

- Vanthology: A Tribute to Van Morrison (2003)

- The String Quartet Tribute to Van Morrison (2003)

- Smooth Sax Tribute to Van Morrison (2005)

- Mystic Piano: Piano Tribute to Van Morrison (2006)

Personal life

[edit]

Family and relationships

[edit]Morrison lived in Belfast from birth until 1964, when he moved to London with the rock group Them.[407] Three years later, he moved to New York after signing with Bang Records. Facing deportation due to visa problems, he managed to stay in the US when his American girlfriend Janet (Planet) Rigsbee, who had a son named Peter from a previous relationship,[408] agreed to marry him.[409] Once married, Morrison and his wife moved to Cambridge, Massachusetts, where he found work performing in local clubs. The couple had one daughter in 1970, Shana Morrison, who has become a singer-songwriter. Morrison and his family moved around America, living in Boston; Woodstock, New York; and a hilltop home in Fairfax, California. His wife appeared on the cover of the album Tupelo Honey. They divorced in 1973.[410][411]

Morrison moved back to the UK in the late 1970s, first settling in London's Notting Hill Gate area.[412] Later, he moved to Bath, where he purchased the Wool Hall studio in January 1994.[413] He also has a home in the Irish seaside village of Dalkey near Dublin, where legal actions were taken against Morrison by two neighbours who objected to Morrison attempting to widen his driveway. The case was taken to court in 2001, with the initial rulings going against Morrison.[414][415][416][417] Morrison pursued the matter all the way to the Irish Supreme Court, but his appeal was denied.[418] A separate case in 2010, in which Morrison's then-wife Michelle took legal action against a different neighbour, who was building a balcony that she felt would overlook the Morrison home and intrude on their privacy, was withdrawn in 2015.[419]

Morrison met Irish socialite Michelle Rocca in the summer of 1992, and they often featured in the Dublin gossip columns, an unusual event for the reclusive Morrison. Rocca also appeared on one of his album covers, Days Like This.[420] The couple married and have two children;[421] a daughter was born in February 2006 and a son in August 2007.[422][423] According to a statement posted on his website, they were divorced in March 2018.[424]

In December 2009, Morrison's tour manager Gigi Lee gave birth to a son, who she asserted was Morrison's and named after him. Lee announced the birth of the child on Morrison's official website, but Morrison denied paternity. Lee's son died in January 2011 from complications of diabetes, and Lee died soon after from throat cancer in October 2011.[425]

Morrison's father died in 1988, and his mother, Violet, died in 2016.[426][427]

Religion and spirituality

[edit]Morrison and his family have been affiliated with St Donard's Parish Church, an Anglican congregation of the Church of Ireland located in east Belfast.[428] During the Troubles, the area was described as "militantly Protestant", although Morrison's parents have always been freethinkers, with his father openly declaring himself an atheist and his mother being connected to Jehovah's Witnesses at one point.[429] Van Morrison was linked to Scientology for a short time and even thanked its founder, L. Ron Hubbard, in one of his songs.[430] Later, he became wary of religion, saying: "I wouldn't touch it with a 10-foot pole." He also said it is important to distinguish spirituality from religion: "Spirituality is one thing, religion ... can mean anything from soup to nuts, you know? But it generally means an organisation, so I don't really like to use the word, because that's what it really means. It really means this church or that church ... but spirituality is different, because that's the individual."[430]

The Troubles