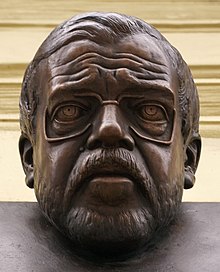

Václav Benda

Václav Benda | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 8 August 1946 |

| Died | 2 June 1999 (aged 52) |

| Nationality | Czech |

| Education | Charles University |

| Occupation(s) | politician, academic |

| Political party | Christian Democratic Party (1990–1996) Civic Democratic Party (1996–1999) |

| Spouse | Kamila Bendová |

| Children | 6 |

Václav Benda (August 8, 1946, Prague – June 2, 1999) was a Czech Roman Catholic activist and intellectual, and mathematician. Under Communist rule in Czechoslovakia, Benda and his wife were rare in that they were devout Roman Catholics among the leadership of the anti-communist dissident organization Charter 77. After the Velvet Revolution, Benda became the head of an organization charged with investigating the former Czechoslovakian secret police and their many informants.

The ideas expressed in Benda's iconic essay A Parallel Polis influenced the thought of other dissidents like Vaclav Havel and Lech Walesa. In the 2010s and 2020s, American Paleoconservative writer Rod Dreher and Russian-American writer Masha Gessen have drawn on these events and ideas from Cold War-era eastern Europe in disparate works for popular audience. The first English translation of Benda's collected samizdat essays was published by St. Augustine's Press in 2017.

Life

[edit]The son of a lawyer, Benda was president of the Students' Academic Council and obtained a doctorate of Philosophy at Charles University in Prague at age 24.[1] His academic career ended when he refused to join the Communist Party in the early 1970s.[2] As a result of his political activities he experienced harassment from the government and economic exclusion, being forced to work for brief periods in a large number of different jobs.[1] With Benda and his wife Kamila's decision during the Soviet-led invasion of August 1968 not to flee the country, he remained at Charles University. Benda completed his doctorate in theoretical cybernetics in 1975, published works on philosophy and mathematics, and then worked as a computer programmer.[3] Benda was active in the dissident movement against the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic, and in 1977 became a signatory to Charter 77.[1]

In 1977, he also wrote a short samizdat essay called "Parallel Polis" (Czech: paralelní polis), calling for his fellow dissidents to abandon hope that the repressive social, economic and political institutions in Czechoslovakia could be changed by protest.[2] Instead, Benda called for new "parallel institutions" to be created, which would be more responsive to human needs and may someday replace the existing corrupt institutions. He argued that as the communist state would drain any efforts at reform, it was better to start new ones than expend energy fighting old ones. The essay was translated into English in 1978.

Benda's role as a spokesman for Charter 77 resulted in him being arrested in May 1979 and charged with subverting the state, for which he was imprisoned until 1983.[1][2] After his release he resumed his role as spokesman.[2] He was also a founder-member of the Committee for the Defense of the Unjustly Prosecuted (VONS).[1] While Benda was imprisoned with Vaclav Havel in Ostrava, they co-wrote a text for the Moscow Helsinki Group in 1980.[1]

A devout Roman Catholic, Benda established the Christian Democratic Party in 1989, becoming chairman in 1990. The party later merged with the Civic Democratic Party. Benda's politics were distinct from his former dissident colleagues, and he became an increasingly isolated figure in Czech politics. He was a defender, with qualifications, of former Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet, a position widely shared in Czech liberal and conservative elite circles.[1][4] Benda stated that Pinochet had "perhaps, his cruel traits, nevertheless they were answers to the extremely undemocratic and extremely cruel advance at the root of international communism."[5]

From June 25 to December 31, 1992, Benda was Chairman of the Chamber of the Nations.

From 1991 to 1998, Benda served as head of the Bureau for Investigating the Crimes of Communist Party officials.[1]

In 1996, he was elected to the Czech Senate for the Prague 1 district, and held the seat until his death in 1999.[2]

Legacy

[edit]Benda's ideas about a Parallel Polis were later revived by a group of scholars at the University of Washington, and a four-story building called Parallel polis has opened in Prague, housing a bitcoin-only cafe, co-working space, makers lab, and "Institute of cryptoanarchy" in Holešovice.[6][7]

In his 2017 book The Benedict Option, author Rod Dreher praised the ideas expressed in Benda's essays and recommended them to American Christians as an example of how to preserve and live their faith in a culture increasingly hostile to it.[8]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h Bourdeaux, Michael (22 June 1999). "Vaclav Benda". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- ^ a b c d e "Vaclav Benda". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ "Obituary: Vclav Benda". The Independent. 6 June 1999.

- ^ Rupprecht, Tobias (2020). "Pinochet in Prague: Authoritarian visions of economic reforms and the State in Eastern Europe, 1980-2000". Journal of Modern European History. 18 (3): 312–323. doi:10.1177/1611894420925024. S2CID 220595021.

- ^ "Human Rights Activist Praises Pinochet". UPI Archives.

- ^ Cuthbertson, Anthony (2014-11-03). "World's First #Bitcoin Only Café Launches in Prague @Paralelni_polis #hackers". International Business Times UK. Retrieved 2016-11-30.

- ^ Ševčík, Pavel. "Paralelni Polis - Paralelní Polis - Paralelní Polis". www.paralelnipolis.cz. Retrieved 2016-11-30.

- ^ "My Night at Vaclav Benda's" by Rod Dreher. American Conservative, March 13, 2018.

Further reading

[edit]- Edited by F. Flagg Taylor IV (2018), The Long Night of the Watchman: Essays by Vaclav Benda, 1977-1989, St. Augustine's Press

- 1946 births

- 1999 deaths

- Mathematicians from Prague

- Czech Roman Catholics

- Christian Democratic Party (Czech Republic) politicians

- Civic Democratic Party (Czech Republic) Senators

- Members of the Chamber of the People of Czechoslovakia (1986–1990)

- Members of the Chamber of the People of Czechoslovakia (1990–1992)

- Members of the Chamber of the People of Czechoslovakia (1992)

- Czechoslovak mathematicians

- Czech mathematicians

- Czechoslovak democracy activists

- Charter 77 signatories

- Czechoslovak prisoners and detainees

- People of the Velvet Revolution

- Recipients of Medal of Merit (Czech Republic)

- 20th-century Czech philosophers

- Charles University alumni

- Czech Roman Catholic writers