Traumatic memories

The management of traumatic memories is important when treating mental health disorders such as post traumatic stress disorder. Traumatic memories can cause life problems even to individuals who do not meet the diagnostic criteria for a mental health disorder. They result from traumatic experiences, including natural disasters such as earthquakes and tsunamis; violent events such as kidnapping, terrorist attacks, war, domestic abuse and rape.[1] Traumatic memories are naturally stressful in nature and emotionally overwhelm people's existing coping mechanisms.[2]

When simple objects such as a photograph, or events such as a birthday party, bring traumatic memories to mind people often try to bar the unwanted experience from their minds so as to proceed with life, with varying degrees of success. The frequency of these reminders diminish over time for most people. There are strong individual differences in the rate at which the adjustment occurs.[3] For some the number of intrusive memories diminish rapidly as the person adjusts to the situation, whereas for others intrusive memories may continue for decades with significant interference to their mental, physical and social well-being.

Several psychotherapies have been developed that change, weaken, or prevent the formation of traumatic memories. Pharmacological methods for erasing traumatic memories are currently the subject of active research. The ability to erase specific traumatic memories, even if possible, would create additional problems and so would not necessarily benefit the individual.

Effects

Biological impact

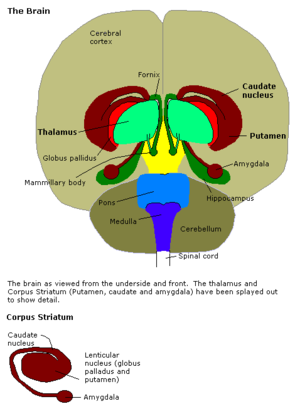

Intense psychological stress caused by unwanted, troublesome memories can cause brain structures such as the amygdala, hippocampus and frontal cortex to become activated, as they process the memory. Related to this, there is some neuroimaging (fMRI) evidence that those who are susceptible to PTSD have a hippocampus with a reduced size.[4] Research has also demonstrated the adrenal activity from intense stress dramatically increases activity in the amygdala and leads to changes in brain functioning as well as altering physiological indicators of stress; heart rate, blood pressure and an increase in salivary enzymes, all of which vary with individual responses to stress.[5]

Children who have been exposed to traumatic events often display hippocampus-based learning and memory deficits. These children suffer academically and socially due to symptoms like fragmentation of memory, intrusive thoughts, dissociation and flashbacks, all of which may be related to hippocampal dysfunction.[3]

Psycho-social impact

People who are feeling distressed by unwanted traumatic memories, which they may constantly be "reliving" through nightmares or flashbacks may withdraw from family or their social circles in order to avoid exposing themselves to reminders of their traumatic memories. Physical aggression, conflicts and moodiness cause dysfunction in relationships with families, spouse, children and significant others.[4] In order to cope with their memories they often resort to substance abuse, drugs or alcohol in order to deal with anxiety. Depression, severe anxiety and fear commonly stem from traumatic memories.[1] If symptoms of apathy, feeling of inability to control impulsive behavior, sleeplessness or irritability persist the person can discuss this with their family doctor or a psychotherapist.[6]

Consolidation

Traumatic memories are formed after an experience that causes high levels of emotional arousal and the activation of stress hormones. These memories become consolidated, stable, and enduring long-term memories (LTMs) through the synthesis of proteins only a few hours after the initial experience. The release of the neurotransmitter Norepinephrine (Noradrenaline) plays a large role in consolidation of traumatic memory. Stimulation of beta-adrenergic receptors during arousal and stress strengthens memory consolidation. Increased release of Norepinephrine inhibits the prefrontal cortex, which plays a role in emotion control as well as extinction or suppression of memory. Additionally, the release also serves to stimulate the amygdala which plays a key role in generating fear behaviors.[7]

Reconsolidation

Memory reconsolidation is a process of retrieving and altering a pre-existing long-term memory. Reconsolidation after retrieval can be used to strengthen existing memories and update or integrate new information. This allows a memory to be dynamic and plastic in nature. Just like in consolidation of memory, reconsolidation, involves the synthesis of proteins. Inhibition of this protein synthesis directly before or after retrieval of a traumatic memory can disrupt expression of that memory.[8] When a memory is reactivated it goes into a labile state, making it possible to treat patients with post-traumatic stress disorder or other similar anxiety based disorders. This is done by reactivating a memory so that it causes the process of reconsolidation to begin. One source described the process this way: "[O]ld information is called to mind, modified with the help of drugs or behavioral interventions, and then re-stored with new information incorporated."[9] There are some serious ethical problems with this process as the reactivation of traumatic memories can be very harmful and in some cases cause anxiety attacks and extreme levels of stress.[10] Inhibition of reconsolidation is possible through pharmacological means. The administration of several different types of protein synthesis antagonists can be used to block protein synthesis that occurs after a traumatic memory is reactivated. The inhibition of creation of new proteins will stop the reconsolidation process and make the memory imperfect.[11]

Pharmacological interventions

The use of chemical agents as a means to alter traumatic memories has a basis in Molecular Consolidation Theory. Molecular Consolidation theory says that memory is created and solidified (or consolidated) by specific chemical reactions in the brain. Initially, memories exist in a plastic, labile state before they are more solidly encoded. It has been argued that memory consolidation occurs more than once- each time a memory is recalled, it returns to a labile state. It states that things which cause memory loss after initial learning can also lead to memory loss after reactivation or retrieval[10] and it is by applying a pharmacological intervention at this plastic point whereby a traumatic memory can be erased.

The importance of the amygdala

The amygdala is an important brain structure when it comes to learning fearful responses, in other words, it influences how people remember traumatic things. An increase in blood flow to this area has been shown when people look at scary faces, or remember traumatic events.[12] Research has also shown that the lateral nucleus of the amygdala is a crucial site of neural changes that occur during fear conditioning.[13]

In tests with rats, lesions to their basolateral amygdala were shown to reduce the memory enhancing effects of glucocorticoids. Likewise, post-training infusions of β-adrenoreceptor antagonists (beta-blocker) systemically or into the basolateral amygdala reduced fear acquisition, while infusions into other brain areas did not.[14][15][16] Consistent with this, infusions of β-receptor agonists enhanced memory consolidation. Researchers conclude that the amygdala is an important mediator of the memory enhancing effects of glucocorticoids and epinephrine.[17]

Anisomycin

The consolidation of memory requires the synthesis (creation) of certain proteins in the amygdala. Disruption of protein synthesis in the amygdala has been shown to prevent long-term memory for fear conditioning.[18][19] Anisomycin inhibits the production of proteins. In tests where it is delivered to the lateral and basal nuclei in the amygdala of rats, the rats demonstrated that they had forgotten fear responses that they had been conditioned to display.

U0 126

U0126 is a MAPK inhibitor, it disrupts the synthesis of the proteins required to reconsolidate memory. Research has shown that administration of this drug in rats is correlated with a reduction in synaptic potentiation in the lateral amygdala. This means that the neurons in this area which are selective for a certain fear memory fire less easily in response to the memory when affected by the drug as compared to the ease with which they fire without the drug present.[20]

Using U0 126, researchers were able to selectively knock out a fear memory for a specific audio tone and leave a fear memory for another audio tone in a group of rats. This was observed by recording brain activity in the amygdala of these rats when presented with tones they had been conditioned to fear.[20]

Propranolol

Propranolol is a blocker for the beta-adrenergic receptors in the amygdala which usually are bound to by stress hormones released by the adrenal gland- epinephrine and norepinephrine.

Research exploring the idea that blocking these receptors would disrupt the creation of proteins necessary for consolidating fearful memories in the amygdala. Propranolol is one such blocker, and in studies was shown to prevent the expression and return of fear in human subjects[21]

Another study showed that emotionally arousing stories generally predicted better memory recall than stories which were less so. Subjects who read or listened to these arousing stories were less able to remember the details in response to multiple choice questions or in free recall when they had been given a dose of propranolol prior to the story exposure.[22]

D-Cycloserine

It has been shown that the NMDA receptors in the amygdala play a pivotal role in extinction (forgetting) and acquisition (remembering)

The normal endogenous compounds which block the activation of NMDA receptors prevent forgetting. Knowing this, researchers hypothesized that hyper-activating these receptors (instead of blocking them) would enhance their activity, and increase forgetting. D-cycloserine is a chemical which enhances (agonist) the activity of the NMDA receptors.[12] When used in rats, D-cycloserine was shown to produce results which reflected this idea. Rats which had been administered it had enhanced levels of forgetting than rats who had not been.

Neuropeptide Y

Neuropeptide Y receptors have a great concentration in the amygdala, which is involved in the modulation of fear.[23] Research where Neuropeptide Y was administered intracerebroventricularly showed that it was important in consolidation of memory because it increased immediate and long-term forgetting. The antagonizing of a subtype of receptor for Neuropeptide Y caused the opposite effects- it decreased the likelihood that a fearful memory would be forgotten.[24]

Psychotherapeutic treatments

Exposure therapy

Exposure therapy involves gradually exposing individuals to a stimuli they find disturbing or fear inducing until it no longer provokes an emotional response. The stimuli can range from commonly feared situations and objects, such as heights or speaking publicly, to seemingly mundane objects and places that have become distressing through a traumatic experience. If someone is exposed to a traumatic experience it is common that being exposed to reminders, including memories, of the event will trigger anxiety attacks, emotional distress and flashbacks. A common mechanism to deal with these potential triggers is to avoid thinking about them and to avoid situations where they may be exposed to them. This can affect quality of life by limiting where someone feels they can go and what a person feels comfortable doing. Evidence has been found linking early traumatic experiences with agoraphobia, an anxiety disorder where individuals fear having panic attacks outdoors.[25]

By repeatedly and carefully having a patient think about or encounter the stimuli and confront the emotions they are feeling, they will experience less and less distress. By systematically targeting distressing memories and stimuli, with exposure therapy, it has been shown levels of depression and symptoms of PTSD decrease significantly.[26][27] Virtual reality can be used to simulate the original conditions of a traumatic event for use in exposure therapy. This is particularly useful when patients believe the memories of their experience are too strong for them to actively search for and retrieve. Virtual reality has been used to treat individuals with PTSD symptoms stemming from the terrorist attacks of 9/11.[28]

Cognitive behavioral therapies

Research has shown several cognitive behavioural therapies to be effective methods of reducing the emotional distress and negative thought patterns associated with traumatic memories in both those suffering from posttraumatic stress disorder and depression.[29] One such therapy is trauma-focused therapy. This therapy involves bringing the most disturbing elements of a traumatic memory to mind and using therapist-guided cognitive restructuring to change the way the memories are thought about. The change in evaluation usually involves highlighting that the feelings of certain death, extreme danger, hopelessness and helplessness within a traumatic memory do not apply to the person now, as they survived the event. The therapy also focuses on extending the memory so it is recalled beyond the most traumatic parts. Extending them to a point where the person felt safe again, so they remember the event in a more complete way with less focus on the negative aspects. As an example, a traumatic memory of wartime combat might be extended to after a battle, to when the person was no longer in immediate danger. In processing the memory in these ways it becomes less likely to intrude into their thoughts as an unwanted flashback.[30] The memory also becomes less vivid, less distressing and seems more distant to the person's present life.

Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR)

Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) is a therapy for treating traumatic memories that involves elements of exposure therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy.[31] Despite controversy remaining in some quarters, EMDR is rated at the highest level of efficacy for PTSD by numerous organizations, most notably by the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies in a comprehensive study of all effective treatments for PTSD.[32] There is an extensive theoretical model called adaptive information processing (AIP) underlying EMDR.[citation needed] The role and mechanism of eye movements, or more generally, bilateral, dual attention stimulation (BLS) is still unclear,[citation needed] and though early studies cast doubt on their necessity for EMDR's efficacy,[citation needed] BLS is still considered an integral part of the system by most practicing therapists.[citation needed]

EMDR begins by identifying troubling memories, cognitions and sensations a patient is struggling with. Then negative thoughts are found that the patient has associated with each memory. While both memory and thought are held in mind the patient follows a moving object with their eyes. After, a positive thought about the memory is discussed in an aim to replace the association the negative thought has to the memory with a preferable thought.[29] Experiments have shown that targeted negative memories are recalled less vividly and with less emotion after treatments with EMDR.[31][33] Skin conductance responses, a measure of stress and arousal, have also shown lower levels when negative memories treated with EMDR were brought to mind.[31]

A possible mechanism for EMDR has been proposed. As memories are recalled they enter a labile state, where they become vulnerable to being forgotten again. Normally these memories would be reconsolidated, becoming stronger and more permanent again. Adding in eye movements creates extra demand on working memory (which keeps currently-used information available). This makes it difficult for all the details of the memory to be held at once. Once the memories are reconsolidated they are less emotional and vivid.[33]

Video gaming

Emily Holmes at the University of Oxford ran an experiment that showed the video game Tetris could be a potential method of reducing the strength of traumatic memories.[34] The experiment involved participants watching emotionally distressing video footage. Compared with a control group the participants who played Tetris experienced far less intrusive and upsetting thoughts about the footage over a week-long period.[34] The ability to recall details of the footage was not impaired by playing Tetris.[35] Another group of participants exposed to the same footage were given a different task as a distractor, a verbal "pub quiz" game. This involved answering trivia questions from a range of topics unrelated to the distressing video footage. Those in the pub quiz condition were more likely to experience flashbacks compared to both a no-task, waiting a comparable amount of time without an activity, and the Tetris conditions. Holmes and colleagues thus concluded that it was not merely that those playing Tetris were distracted but that they were distracted in a way that served to disrupt the formation of unwanted and intrusive memories.[35]

The explanation given for the success of administering Tetris as opposed to other interventions is that Tetris draws heavily on visuospatial processing power. Because the brain only has a limited supply of resources to process information, playing Tetris hinders the ability of the brain to focus on other visual information, such as traumatic images.[34] However, the details of the event can still be thought of and rehearsed verbally, as Tetris should not interfere with verbal processes of the brain. This explains why participants could remember the details of the footage they watched but why they still experienced fewer flashbacks.

Neuroscience has shown that memories are vulnerable to disruption for several hours after they form.[35] Holmes and colleagues proposed that because of this visuospatial distractors like Tetris, if administered within six hours of a traumatic event could help prevent symptoms of flashbacks. Also there is some evidence that memories can become vulnerable to disruption even at longer periods of time in a process known as reconsolidation.[34]

Ethical concerns

The prospect of memory erasure or alteration raises ethical issues. Some of these concern identity, as memory seems to play a role in how people perceive themselves. For example, if a traumatic memory were erased, a person might still remember related events in their lives, such as their emotional reactions to later experiences. Without the original memory to give them context, these remembered events might prompt the subjects to see themselves as emotional or irrational people.[36] In the United States, the President's Council on Bioethics devoted a chapter in its October 2003 report Beyond Therapy to the issue.[37][38] The report discourages the use of drugs that blunt the effect of traumatic memories, warning against treating human emotional reactions to life events as a medical issue.[37]

Issues of self-deception arise when altering memories as well. Avoiding the pain and difficulty of dealing with a memory by taking a drug may not be an honest method of coping. Instead of dealing with the truth of the situation a new altered reality is created where the memory is dissociated from pain, or the memory is forgotten altogether.[36][37] Another issue that arises is exposing patients to unnecessary risk. Traumatic experiences do not necessarily produce a long term traumatic memory, some individuals learn to cope and integrate their experience and it stops affecting their lives quite quickly. If drug treatments are administered when not needed, as when a person could learn to cope without drugs, they may be exposed to side effects and other risks without cause.[38] Loss of painful memories may actually end up causing more harm in some cases. Painful, frightening or even traumatic memories can serve to teach a person to avoid certain situations or experiences. By erasing those memories their adaptive function, to warn and protect individuals may be lost.[36][37] Another possible result of this technology is a lack of tolerance. If the suffering induced by traumatic events were removable, people may become less sympathetic to that suffering, and put more social pressure on others to erase the memories.[36]

Despite potential risks and abuses, it can still be justifiable to erase traumatic memories when their presence is so disruptive to some and overcoming them can be a difficult process.[38]

References

- ^ a b Berger, FK (2 February 2016). "Post-traumatic stress disorder". MedlinePlus. United States National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health. Archived from the original on 4 April 2017.

- ^ van der Kolk, BA; Fisler, R (October 1995). "Dissociation and the Fragmentary Nature of Traumatic Memories: Overview and exploratory study". Journal of Traumatic Stress. 8 (4): 505–25. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.487.1607. doi:10.1002/jts.2490080402. PMID 8564271.

- ^ a b Levy, B; Anderson, M (2008). "Individual differences in the suppression of unwanted memories: The executive deficit hypothesis". Acta Psychologica. 127 (3): 623–635. doi:10.1016/j.actpsy.2007.12.004. ISSN 0001-6918. PMID 18242571.

- ^ a b Bremner, Douglas J. (2000). The Lasting Effects of Psychological Trauma on Memory and the Hippocampus. [1]

- ^ Cousijn, H.; Rijpkema, M.; Qin, S.; van Marle, H. J. F.; Franke, B.; Hermans, E. J.; van Wingen, G.; Fernandez, G. (2010). "Acute stress modulates genotype effects on amygdala processing in humans". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 107 (21): 9867–9872. Bibcode:2010PNAS..107.9867C. doi:10.1073/pnas.1003514107. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 2906860. PMID 20457919.

- ^ MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia. http://www.nim.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/000925.htm[permanent dead link]

- ^ Dabiec, J. & Altemus, M., "Toward a New Treatment for Traumatic Memory" Archived 2011-07-25 at the Wayback Machine,The Dana Foundation, September 01, 2006.

- ^ Suzuki, A.; Josselyn, SA; Frankland, PW; Masushige, S; Silva, AJ; Kida, S (2004). "Memory Reconsolidation and Extinction Have Distinct Temporal and Biochemical Signatures". Journal of Neuroscience. 24 (20): 4787–4795. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5491-03.2004. ISSN 0270-6474. PMC 6729467. PMID 15152039.

- ^ Romm, Cari (August 27, 2014). "Changing Memories to Treat PTSD". The Atlantic Health. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- ^ a b Nader, Karim; Schafe, Glenn E.; LeDoux, Joseph E. (2000). "The labile nature of consolidation theory". Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 1 (3): 216–219. doi:10.1038/35044580. ISSN 1471-0048. PMID 11257912. S2CID 5765968.

- ^ Przybyslawski, J; Sara, S (1997). "Reconsolidation of memory after its reactivation". Behavioural Brain Research. 84 (1–2): 241–246. doi:10.1016/S0166-4328(96)00153-2. ISSN 0166-4328. PMID 9079788. S2CID 4000086.

- ^ a b Davis, Michael; Myers, Karyn M.; Ressler, Kerry J.; Rothbaum, Barbara O. (2005). "Facilitation of Extinction of Conditioned Fear by D-Cycloserine. Implications for Psychotherapy". Current Directions in Psychological Science. 14 (4): 214–219. doi:10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00367.x. ISSN 0963-7214. S2CID 145766711.

- ^ Maren, Stephen (2005). "Synaptic Mechanisms of Associative Memory in the Amygdala" (PDF). Neuron. 47 (6): 783–786. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2005.08.009. hdl:2027.42/61962. ISSN 0896-6273. PMID 16157273. S2CID 11574156.

- ^ Giustino, Thomas F.; Seemann, Jocelyn R.; Acca, Gillian M.; Goode, Travis D.; Fitzgerald, Paul J.; Maren, Stephen (December 2017). "β-Adrenoceptor Blockade in the Basolateral Amygdala, But Not the Medial Prefrontal Cortex, Rescues the Immediate Extinction Deficit". Neuropsychopharmacology. 42 (13): 2537–2544. doi:10.1038/npp.2017.89. ISSN 1740-634X. PMC 5686500. PMID 28462941.

- ^ Wu, Yan; Li, Yonghui; Yang, Xiaoyan; Sui, Nan (January 2014). "Differential effect of beta-adrenergic receptor antagonism in basolateral amygdala on reconsolidation of aversive and appetitive memories associated with morphine in rats". Addiction Biology. 19 (1): 5–15. doi:10.1111/j.1369-1600.2012.00443.x. ISSN 1369-1600. PMID 22458530. S2CID 6175409.

- ^ Estrade, Lucile; Cassel, Jean-Christophe; Parrot, Sandrine; Duchamp-Viret, Patricia; Ferry, Barbara (2018-09-10). "Microdialysis Unveils the Role of the α2-Adrenergic System in the Basolateral Amygdala during Acquisition of Conditioned Odor Aversion in the Rat" (PDF). ACS Chemical Neuroscience. 10 (4): 1929–1934. doi:10.1021/acschemneuro.8b00314. ISSN 1948-7193. PMID 30179513. S2CID 52156282.

- ^ McGaugh, J. L. (2000). "Memory - a Century of Consolidation". Science. 287 (5451): 248–251. Bibcode:2000Sci...287..248M. doi:10.1126/science.287.5451.248. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 10634773.

- ^ Nader, Karim; Schafe, Glenn E.; Le Doux, Joseph E. (2000). "Fear memories require protein synthesis in the amygdala for reconsolidation after retrieval". Nature. 406 (6797): 722–726. Bibcode:2000Natur.406..722N. doi:10.1038/35021052. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 10963596. S2CID 4420637.

- ^ "Anisomycin - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics". www.sciencedirect.com. Retrieved 2022-05-05.

- ^ a b Doyère, Valérie; Dębiec, Jacek; Monfils, Marie-H; Schafe, Glenn E; LeDoux, Joseph E (2007). "Synapse-specific reconsolidation of distinct fear memories in the lateral amygdala". Nature Neuroscience. 10 (4): 414–6. doi:10.1038/nn1871. ISSN 1097-6256. PMID 17351634. S2CID 38332643.

- ^ Kindt, Merel; Soeter, Marieke; Vervliet, Bram (2009). "Beyond extinction: erasing human fear responses and preventing the return of fear". Nature Neuroscience. 12 (3): 256–258. doi:10.1038/nn.2271. ISSN 1097-6256. PMID 19219038. S2CID 5948908.

- ^ Cahill, Larry; Prins, Bruce; Weber, Michael; McGaugh, James L. (1994). "β-Adrenergic activation and memory for emotional events". Nature. 371 (6499): 702–704. Bibcode:1994Natur.371..702C. doi:10.1038/371702a0. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 7935815. S2CID 4337182.

- ^ Fendt, Markus; Bürki, Hugo; Imobersteg, Stefan; Lingenhöhl, Kurt; McAllister, Kevin H.; Orain, David; Uzunov, Doncho P.; Chaperon, Frederique (2009). "Fear-reducing effects of intra-amygdala neuropeptide Y infusion in animal models of conditioned fear: an NPY Y1 receptor independent effect". Psychopharmacology. 206 (2): 291–301. doi:10.1007/s00213-009-1610-8. ISSN 0033-3158. PMID 19609506. S2CID 22996908.

- ^ Gutman, A. R.; Yang, Y.; Ressler, K. J.; Davis, M. (2008). "The Role of Neuropeptide Y in the Expression and Extinction of Fear-Potentiated Startle". Journal of Neuroscience. 28 (48): 12682–12690. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2305-08.2008. ISSN 0270-6474. PMC 2621075. PMID 19036961.

- ^ Faravelli C; Webb, T; Ambonetti, A; Fonnesu, F; Sessarego, A (1985). "Prevalence of traumatic early life events in 31 agoraphobic patients with panic attacks". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 142 (12): 1493–1494. doi:10.1176/ajp.142.12.1493. PMID 4073319.

- ^ Keane T.M.; Fairbank J.A.; Caddell J.M.; Zimering R.T. (1989). "Implosive (flooding) therapy reduces symptoms of PTSD in Vietnam combat veterans". Behavior Therapy. 20 (2): 245–260. doi:10.1016/S0005-7894(89)80072-3.

- ^ Onyut L.P.; et al. (2005). "Narrative exposure therapy as a treatment for child war survivors with posttraumatic stress disorder: two case reports and a pilot study in an African refugee settlement". BMC Psychiatry. 5 (1): 7. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-5-7. PMC 549194. PMID 15691374.

- ^ Difede, Joann; Hoffman, Hunter G. (2002). "Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy for World Trade Center Post-traumatic Stress Disorder: A Case Report". CyberPsychology & Behavior. 5 (6): 529–535. doi:10.1089/109493102321018169. ISSN 1094-9313. PMID 12556115. S2CID 2986683.

- ^ a b Tullis, K.F., Wescott, C.L., & Winton, T.R. A theory on the use of cognitive behavioural therapy (cbt) plus eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (emdr) to reduce suicidal thoughts in childhood trauma victims. http://www.ktullis.com/EMDR_Study/EMDR_STUDY.pdf.

- ^ Hirsch, C; Holmes, E (2007). "Mental imagery in anxiety disorders". Psychiatry. 6 (4): 161–165. doi:10.1016/j.mppsy.2007.01.005. ISSN 1476-1793.

- ^ a b c Schubert, Sarah J.; Lee, Christopher W.; Drummond, Peter D. (2011). "The efficacy and psychophysiological correlates of dual-attention tasks in eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR)". Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 25 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.06.024. ISSN 0887-6185. PMID 20709492.

- ^ Foa, Edna B.; Keane, Terence M.; Friedman, Matthew J.; Cohen, Judith A. (2009). Effective Treatments for PTSD, Practice Guidelines from the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies. Guilford. pp. 3, 279–305. ISBN 978-1-60623-001-5.

- ^ a b van den Hout, Marcel A.; Engelhard, Iris M.; Rijkeboer, Marleen M.; Koekebakker, Jutte; Hornsveld, Hellen; Leer, Arne; Toffolo, Marieke B.J.; Akse, Nienke (2011). "EMDR: Eye movements superior to beeps in taxing working memory and reducing vividness of recollections". Behaviour Research and Therapy. 49 (2): 92–98. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2010.11.003. ISSN 0005-7967. PMID 21147478.

- ^ a b c d Bell, Vaughan; Holmes, Emily A.; James, Ella L.; Coode-Bate, Thomas; Deeprose, Catherine (2009). Bell, Vaughan (ed.). "Can Playing the Computer Game "Tetris" Reduce the Build-Up of Flashbacks for Trauma? A Proposal from Cognitive Science". PLOS ONE. 4 (1): e4153. Bibcode:2009PLoSO...4.4153H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0004153. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 2607539. PMID 19127289.

- ^ a b c Hashimoto, Kenji; Holmes, Emily A.; James, Ella L.; Kilford, Emma J.; Deeprose, Catherine (2010). Hashimoto, Kenji (ed.). "Key Steps in Developing a Cognitive Vaccine against Traumatic Flashbacks: Visuospatial Tetris versus Verbal Pub Quiz". PLOS ONE. 5 (11): e13706. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...513706H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0013706. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 2978094. PMID 21085661.

- ^ a b c d Evers, Kathinka (2007). "Perspectives on Memory Manipulation: Using Beta-Blockers to Cure Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder". Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics. 16 (2): 138–46. doi:10.1017/S0963180107070168. ISSN 0963-1801. PMID 17539466. S2CID 2354231.

- ^ a b c d Grau, Christopher (2006). "Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind and the Morality of Memory". Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism. 64 (1): 119–133. doi:10.1111/j.0021-8529.2006.00234.x. ISSN 0021-8529.

- ^ a b c Glannon, W (2006). "Psychopharmacology and memory". Journal of Medical Ethics. 32 (2): 74–78. doi:10.1136/jme.2005.012575. ISSN 0306-6800. PMC 2563336. PMID 16446410.

External links

- "Happy Souls" Chapter 5 of "Beyond Therapy: Biotechnology and the Pursuit of Happiness" by The President's Council on Bioethics, December 2003