Battle of Radzymin (1920)

| Battle of Radzymin | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Battle of Warsaw during the Polish–Soviet War | |||||||

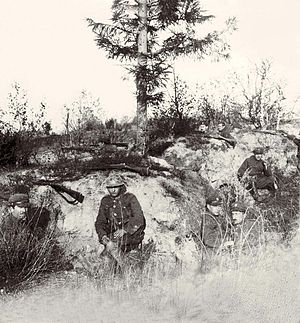

Polish infantry in a trench outside Radzymin. The soldier in the centre wears an Adrian helmet, while the rest have maciejówka caps inherited from the Polish Legions. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Vitovt Putna Ivan Smolin |

Jan Rządkowski Józef Haller Franciszek Latinik | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

21st Rifle Division 27th Rifle Division |

10th Infantry Division 11th Infantry Division 1st Lithuanian-Belarusian Division[a] | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

15,000 soldiers 91 artillery pieces 390 machine guns[1] |

17,000 soldiers 109 artillery pieces 220 machine guns[2] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Heavy[3] | c. 3,040 killed and wounded[4] | ||||||

Location within Poland | |||||||

The Battle of Radzymin (Polish: Bitwa pod Radzyminem) took place during the Polish–Soviet War (1919–21). The battle occurred near the town of Radzymin, some 20 kilometres (12 mi) north-east of Warsaw, between August 13 and 16, 1920. Along with the Battle of Ossów and the Polish counteroffensive from the Wieprz River area, this engagement was a key part of what later became known as the Battle of Warsaw. It also proved to be one of the bloodiest and most intense battles of the Polish–Soviet War.

The first phase of the battle began on August 13 with a frontal assault by the Red Army on the Praga bridgehead. The Russian forces captured Radzymin on August 14 and breached the lines of the 1st Polish Army, which was defending Warsaw from the east. Radzymin changed hands several times in heavy combat. Foreign diplomats, with the exception of the British and Vatican ambassadors, hastily left Warsaw.

The plan for the battle was straightforward for both sides. The Russians wanted to break through the Polish defences to Warsaw, while the Polish aim was to defend the area long enough for a two-pronged counteroffensive from the south, led by General Józef Piłsudski, and north, led by General Władysław Sikorski, to outflank the attacking forces.

After three days of intense fighting, the corps-sized 1st Polish Army under General Franciszek Latinik managed to repel a direct assault by six Red Army rifle divisions at Radzymin and Ossów. The struggle for control of Radzymin forced General Józef Haller, commander of the Polish Northern Front, to start the 5th Army's counterattack earlier than planned. Radzymin was recaptured on August 15, and this victory proved to be one of the turning points of the battle of Warsaw. The strategic counteroffensive was successful, pushing Soviet forces away from Radzymin and Warsaw and eventually crippling four Soviet armies.[citation needed]

Background

[edit]Following the failure of the Kiev offensive, the Polish armies retreated westwards from Central Belarus and Ukraine.[5] Although the Bolshevik forces failed to surround or destroy the bulk of the Polish Army, most Polish units were in dire need of fresh reinforcements.[5] The Polish command hoped to halt the advancing Russian forces in front of Warsaw, the capital of Poland.[6] At the same time General (later Marshal of Poland) Józef Piłsudski was to lead a flanking manoeuvre from the area of the Wieprz River, while General Władysław Sikorski's 5th Army was to leave the Modlin Fortress and head north-east, to cut off the Russian forces heading westwards, to the north of the bend of the Vistula and Bugonarew and on towards Pomerania. However, for this plan to succeed, it was vital that Polish forces hold Warsaw.[7]

Prelude

[edit]The defence of Warsaw was organized by the 1st Polish Army under General Franciszek Latinik and by a part of the Northern Front under General Józef Haller.[8] The army consisted of four understrength infantry divisions: the 8th, 11th, and 15th, with the 1st Lithuanian-Belarusian Division in reserve.[8] In addition, it had at its disposal the battle-weary 10th Infantry Division, two Air Groups (four escadrilles in total), 293 pieces of artillery and three armoured trains.[8]

The city was to be surrounded by four lines of defence. The outermost ran some 24 kilometres (15 mi) to the east of Warsaw: to the east of Zegrze Fortress, then along the river Rządza to Dybów and south through Helenów, Nowa Czarna and the Białe Błota marshes east of Wołomin. From there it ran through Leśniakowizna, dense forests occupied by artillery training grounds, and then along the Okuniew–Wiązowna–Vistula line.[9]

The second line ran a mile closer to Warsaw, along the lines of partially preserved First World War-era trenches built by German and Russian armies in 1915, separated by a no man's land.[10] It ran from the banks of the river Bugonarew at Fort Beniaminów, along the Struga–Zielonka–Rembertów-Zakręt–Falenica line. The two most prominent pivots of this line were the towns of Radzymin and Wołomin. The third line of defence ran in the immediate vicinity of the right-bank borough of Praga, while the Vistula River bridgeheads formed the final fourth line.[11]

The 11th Polish Infantry Division was dispatched to Radzymin on August 8 in order to prepare the city's defences for the expected arrival of Bolshevik forces. While the unit's core was formed around veterans of the 2nd Polish Rifle Division of the French-equipped and trained Blue Army, it had been recently reinforced with fresh, but raw, recruits. The Poles set up defences in front of the town, utilising some earlier German and Russian First World War trenches and digging new positions.[10] The Polish line ran some 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) in front of the town, from the unfinished 1909 Fort Beniaminów at the banks of the river Bugonarew through Mokre to Dybów. The following day the 6th Russian Rifle Division captured Wyszków[12] some 30 kilometres (19 mi) to the north-east. On August 12 the Polish 1st Lithuanian–Belarusian Division abandoned the first line of defence and withdrew through Radzymin towards Warsaw. Radzymin now found itself at the front line; by nightfall, the first Russian forces appeared in front of Ruda and Zawady, two villages manned by the Polish 48th Infantry Regiment, and Russian artillery shelled Radzymin for the first time.[13]

Battlefield

[edit]From the north, Warsaw, which spans the Vistula, was effectively shielded by the Vistula, Bug and Narew rivers. The Red Army's lack of modern engineering equipment for the river crossings inhibited a flanking attack of Warsaw from the west, which had been Russia's historical path of attack,[14] towards Płock, Włocławek and Toruń, where their forces could cross the Vistula and strike Warsaw from the west and north-west over permanent bridges there. While a ring of 19th- and early 20th-century Russian-built forts, part of the Warsaw Fortress, ran mostly along the western side of the Vistula,[15] these fortifications lay in ruins; Russian forces began demolition in 1909 and had destroyed most by the time of their withdrawal from Warsaw in 1915, during the First World War.[15][g]

The most expedient approach for a large-scale assault on Warsaw was from the east. The terrain was mostly flat; numerous roads converged radially along an arc from the Modlin Fortress to the north (where the Narew flows into the Vistula), to Legionowo, Radzymin, and Mińsk Mazowiecki directly to the east.[16] Meanwhile, the only permanent defences in the area of Radzymin were the incomplete Fort Beniaminów and a line of First World War trenches west of Radzymin, neglected since their construction by Russians and Germans in 1915.[10]

Opposing forces

[edit]

The first and second lines of Polish defences were manned by regular forces. These included three Polish infantry divisions: the 11th (from the Bug River to Leśniakowizna), the 8th (Leśniakowizna to Okuniew) and the 15th (Okuniew to the Vistula River). The 1st Army also held the newly arrived 1st Lithuanian-Belarusian Division in reserve (Marki–Kobyłka),[a] while the Northern Front's headquarters reserves consisted of the 10th Infantry Division and some smaller units. The third line was manned by units of mobilised State Police and a variety of volunteer units of low combat value. Out of those units, initially, only the 11th Division under Colonel Bolesław Jaźwiński took part in the fight. Its 48th Kresy Rifles Regiment (Colonel Łukowski) manned the Bugonarew-Mokre line, the 46th Kaniów Rifles Regiment (Colonel Krzywobłocki) manned the Mokre-Czarna perimeter, and the 47th Kresy Rifles Regiment (Lt. Colonel Szczepan) manned the Czarna–Leśniakowizna line. To the south of the 11th Division were positions around Wołomin manned by the 8th Infantry Division, consisting of the 36th, 21st and 33rd Infantry Regiments, as well as the 13th Infantry Regiment held in reserve, which later took part in the Battle of Ossów.[21]

The combat value of Polish units is difficult to assess as they included fresh recruits of the so-called Volunteer Army, veterans of First World War, battle-hardened soldiers who fought in earlier stages of the Polish-Bolshevik War, and civilians with virtually no combat training. Prior to the battle, the 46th Regiment received 700 reinforcements: mostly deserters from various formations, a battalion of volunteer sentry guards and march companies of sappers.[22] The 11th Infantry Division, nominally 9000 men strong, in practice had only 1500 soldiers in first-line units.[23] The situation for the Polish Army was so dire that some of the soldiers sent as reinforcements had reportedly "never seen a rifle in their lives".[24] In addition, most units to make a stand at Radzymin were exhausted after surviving a 600-kilometre (370 mi) retreat from Belarus.[25] However, the Polish side had superior intelligence and aerial superiority.[26][27][d]

The two Russian divisions assaulting Radzymin were battle-hardened Siberian divisions led by experienced front-line commanders.[28] Both divisions were as exhausted as their opponents, whom they had chased all the way from Belarus.[29] However, prior to the battle both divisions received reinforcements from other units, instead of fresh recruits, and were much superior in manpower to other Russian units on the Polish front.[29] Later, in his monograph on the war, Marshal of Poland Józef Piłsudski remarked that the commanding officer of the 27th Rifle Division had achieved what was unheard of in the Polish Army despite numerous attempts: putting rear echelons and stragglers of his division into front-line service.[30] This was indeed a problem for both armies, as the number of "bayonets and sabres", or soldiers fighting in the first line, was at all times smaller than the number of second echelon troops.[24] On August 15 Polish intelligence reported the strength of the Russian forces as "three to four standard Russian divisions".[7] Even post-war memoirs by General Żeligowski mention "[t]hree Russian infantry divisions, that is 27 battalions, though admittedly understrength, against one of our own",[31] though in fact the Russian forces only had two divisions.[32][33]

Battle

[edit]August 13

[edit]

Both Polish and Russian planners expected an attack on Warsaw—and Radzymin in particular—from the east. Yet the first fights started to the north-east of the Polish capital.[34] Warsaw was to be assaulted from the east by the 16th Red Army. At the same time the 14th Red Army (under Ieronim Uborevich) captured Wyszków and started a fast march westwards,[12] towards Toruń. It was then to cross the lower Vistula and assault Warsaw from the north-west. However, its 21st Rifle Division remained on the south side of the Bug River and headed for Warsaw directly, under orders from Russia's Commissar of War Leon Trotsky.[35] Aided by the Russian 27th Rifle Division, it came into contact with the Polish forces at Radzymin on August 12, and prepared for an assault the following morning.[31]

The Soviet probing attack began at 07:00 hours, but the 21st Rifle Division achieved no breakthrough. After the Soviets had been repelled, the defending 11th Infantry Division received some artillery reinforcements. The artillery commanders wanted to use the church tower of Radzymin as an observation post and to move the batteries forward, closer to the front line.[31] However, before the relocation of the artillery was complete, a new Soviet attack began at around 17:00, this time carried out by four brigades of the 21st and 27th Rifle Divisions,[e] reinforced with 59 artillery pieces.[36] The Russians achieved a 3:1 superiority in firepower.[23] Deprived of artillery support, the inexperienced and overstretched[31][34] 1/46th Infantry Regiment, defending the village of Kraszew, broke, and the Soviets gained entry to Radzymin.[22] The Polish unit withdrew in panic,[36] and soldiers left their arms and backpacks behind.[37] One of the artillery officers noted that the Russians achieved complete tactical surprise: "I ordered my dinner prepared when my aide came shouting 'Lieutenant Sir, the Reds are in the city'".[38]

The retreat was made even more serious by the fact that the gendarmes, tasked with stabilising the front and catching deserters, also fled in panic.[4] The town itself was badly damaged, and the commanding officer of the 46th Regiment, Colonel Bronisław Krzywobłocki, was forced to order the retreat of the remainder of his forces south-west from the town.[4] The rest of the division had no option but to fall back to the line of First World War trenches.[31] During the chaotic withdrawal all the artillery sub-units got lost. By 19:00 hours the town was in Russian hands.[9]

Although the Polish division was defeated, the Russian forces did not pursue.[4] This allowed the Poles to mount a night counterattack. A single machine gun battalion attacked a position behind Radzymin. While ultimately unsuccessful, the battalion forced the Russian troops to remain stationary overnight, giving the Poles badly needed time to regroup and receive reinforcements, which came in the form of a single regiment from the 1st Lithuanian-Belarusian Division. Instead of retreating to the third line of defences, the Poles remained outside the town, hoping to retake it the following day.[39]

News of the defeat at Radzymin reached Warsaw the same day,[40] causing panic among both the government and ordinary people.[28][34][40] The following day the battlefield was visited by, among others, Prime Minister Wincenty Witos, papal nuncio Achille Ratti (the future Pope Pius XI),[41] Maciej Rataj and General Józef Haller, the commanding officer of the Northern Front. General Haller's dispatch of 01:00 hours the same night called the Polish defeat at Radzymin "ignominious", and ordered the commanding officers of the 46th Infantry Regiment and divisional artillery to be immediately court-martialled.[33] The commanding officer of the 46th Regiment was immediately relieved of command and replaced with Major Józef Liwacz.[36][b]

The gravity of the situation was well understood by the Polish Commander-in-Chief Józef Piłsudski, who remarked that all the battle plans for his counteroffensive were based on the assumption that Warsaw would hold,[34] and suggested to General Tadeusz Rozwadowski that he reinforce the Radzymin area with any forces available, including an "en masse tank attack".[7] Despite this suggestion, out of 49 tanks of the 1st Tank Regiment available in Warsaw at that time, only about six took part in the battle.[42][c] The loss of Radzymin also forced General Władysław Sikorski's 5th Army, fighting north of the Bug River and along the Vistula, to start a counteroffensive from the Modlin Fortress earlier than planned.[34] Rozwadowski and General Maxime Weygand, a member of the French Military Mission to Poland, even suggested that Piłsudski also hasten his preparations for a counteroffensive, but he refused and decided to follow the original plans.[33][f]

The Russians considered the capture of Radzymin a crucial accomplishment. The Polish intelligence intercepted and decrypted a euphoric, but a completely false, report by the Revolutionary Military Committee of the 3rd Army dispatched to Moscow, informing the Russian government that "the brave units of the 3rd Army have captured the town of Radzymin on August 13th, at 23:00 hours. In pursuit of the enemy, they are not further than 15 versts from Praga. (...) The workers of Warsaw can already sense that their liberation is near. The revolution in Warsaw is ripe. Workers demand that the city be handed over to the Red Army without a fight, threatening to prevent armed soldiers from leaving the city [for the front]. The White Poland is dying".[3] The commanding officer of the Russian 3rd Army, Vladimir Lazarevich, informed Tukhachevsky that "Poland is now on fire. Only one more push is needed and the Polish fracas will be over".[36]

To counter the threat of a Russian breakthrough, General Latinik ordered General Jan Rządkowski to assault the town the following day with all available forces. To strengthen the assault, the 11th Infantry Division (under Colonel Bolesław Jaźwiński) was drawn from the reserves and dispatched to join the assault which was scheduled for 05:00 hours the following morning.[43] However, the Polish forces were far from sufficient for the task. Rządkowski argued that he had been promised substantial reinforcements which did not arrive. The battle-hardened Siberian Brigade was at that time tied down in the Modlin Fortress, although the promised cavalry units did arrive—but without their ammunition trains.[44]

August 14

[edit]

The plans for the Polish assault had to be changed due to unexpected Russian actions. The Polish forces expected heavy opposition from at least two Russian divisions. However, in the morning the Russian 21st Division resumed its advance along the Białystok–Warsaw road towards Marki and Warsaw, while the 27th started its march towards Jabłonna.[38] The 21st Division achieved some early successes when its 5th and 6th Rifle Brigades pushed the Poles back from the Czarna River some 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) to the west.[45] However, at the same time it was advancing right in front of Polish forces which were preparing to assault Radzymin.[38] At 10:15 hours the Polish 81st and 85th Infantry Regiments from the 1st Lithuanian-Belarusian Division assaulted the left flank of the unsuspecting Russians,[46] continued along the Warsaw–Białystok road, and broke through to the town.[45] The attack was led by Lieutenant Colonel Kazimierz Rybicki, who had personally witnessed the defeat of the 46th Regiment the previous day, on his day off.[38] This time spirits were high and the Polish infantry advanced in order, with officers in the first line and the soldiers singing Dąbrowski's Mazurka.[46] By noon the town was liberated.[46]

The success did not last long, as the Russian 27th Rifle Division turned around and arrived at Radzymin just in time for its 81st Brigade to push the exhausted Polish forces back towards the village of Słupno.[38][47] Threatened by further attacks from Słupno and Wieliszew, the 85th Regiment retreated after suffering heavy casualties, including the commanding officer of the 1st Battalion, Captain Ryszard Downar-Zapolski.[31] This time the Soviet 81st Rifle Brigade (27th Rifle Division) pursued the Poles and managed to pierce Polish defences near Wólka Radzymińska and Dąbkowizna, breaking through the second line of defences, which were the last before the city limits. The Polish headquarters at Warsaw was "petrified to hear of the complete destruction of the 19th [Lithuanian-Belarusian] Division", a report that fortunately for the Poles proved to be false.[16] The threat to the northern flank was halted, with heavy casualties on both sides, thanks to the intervention of the division's commanding officer Jan Rządkowski, as well as Front commanding officer Józef Haller, who arrived on the battlefield to personally organise an ad hoc line of defence west of Wólka Radzymińska,[38] with Polish artillery units shelling the advancing Russians with direct fire.[46][48] The Soviet advance was halted, and this time chaos in the Polish ranks was avoided, but again lack of reinforcements behind the main line of defences proved a serious problem.[38]

In the evening Generals Lucjan Żeligowski, Józef Haller, Jan Rządkowski and Franciszek Latinik met in Jabłonna and again in Struga to prepare a plan for retaking Radzymin once again. It was decided that, since the Soviet 27th Division was bogged down around Radzymin and had not resumed its march towards Jabłonna, the Polish 10th Infantry Division was no longer needed in that sector, and instead could be used to achieve a breakthrough at Radzymin. The division was relocated to Nieporęt, where General Rządkowski discovered the artillery units that were believed to have been destroyed by the Russians the previous day. A single battalion from the 28th Kaniów Rifles Regiment from the 10th Division, led by 1st Lieutenant Stefan Pogonowski, was ordered to entrench in a forest near Wólka Radzymińska and organise an ambush. The rest of the Polish forces were to start an all-out assault at 05:00 hours the following morning, with General Żeligowski in command over the ad hoc corps.[49] The forces amassed for the assault had a nominal strength of 17,000 infantry, 109 artillery pieces, and 220 machine guns.[49]

In the evening the 5th Army, operating north of the Bug and Narew rivers with its base of operations in the Modlin Fortress, started a limited counteroffensive with the aim of lessening the pressure on the Polish forces at Radzymin.[33] Grossly outnumbered, the 5th Army could not break through the Russian lines, and got bogged down in intense fights along the Wkra river.[50] However, although initially unsuccessful, the Polish attack prevented the Soviet 5th, 15th and 16th Armies from reinforcing the two divisions already committed to Radzymin.[33] Only the 4th Red Army, the furthest from the battlefield, operating in the north along the East Prussian border and moving towards Toruń, kept advancing almost unopposed.[33] This, however, did not pose an immediate threat to the defenders of Warsaw, as its advance was finally halted at the outskirts of Włocławek, and it was forced to start a hasty retreat eastwards.[51]

August 15

[edit]In the early hours of August 15 the Russian forces resumed their attacks on the Polish lines, intending to break through the second line of defences to the area of Nieporęt and Jabłonna.[46] However, as they bypassed a small forest outside Wólka Radzymińska, they were assaulted from the rear by the 1st Battalion of the 28th Infantry Regiment, which had been concealed there earlier. Simultaneously, the remainder of the 28th Regiment began a badly coordinated and half-hearted attack from Nieporęt. Both Polish assaults were bloodily repelled, with the casualties including Lieutenant Pogonowski who was posthumously awarded the Virtuti Militari medal for his bravery leading the charge, but they did force the Russians to retreat to their initial positions.[46]

When the front-line stabilised, the Polish headquarters threw all its reserves into a counterattack. Beniaminów was reinforced with the 29th Infantry Regiment. The Polish attack began around 05:30, after a 20-minute artillery barrage.[45] Soon the entire 10th Infantry Division started a push along the southern bank of the Bugonarew river in order to outflank the Russian forces from the north, while the 1st Lithuanian-Belarusian Division pushed directly towards the town. Although the Russian side had superior artillery and brought several Austin-Putilov armoured cars, this time the Polish assault was supported by five Renault FT tanks and numerous aircraft.[50] Despite suffering from mechanical failures, the tanks successfully broke through the Russian lines, and the infantry of the 85th "Wilno Rifles" Regiment from the 1st Lithuanian-Belarusian Division followed them into the town.[46] After a short struggle the Polish forces once again controlled the town. However, as soon as it was taken, General Żeligowski decided to reorganise his division and could not support the 85th Regiment with fresh forces.[46] Yet another successful counterattack by the Russian 61st and 62nd Infantry Brigades forced the Polish 1st Division to retreat back to its initial positions.[46]

At the same time, on the northern flank, the 10th Division was much more successful. Instead of waiting for orders from General Żeligowski, the commanding officer of the 10th Division, Lieutenant Colonel Wiktor Thommée, started a push along the southern bank of the Bugonarew.[46] The 28th and 29th Kaniów Rifles Infantry Regiments managed to reach the village of Mokre, on a small hill overlooking Radzymin and the Białystok-Warsaw road, directly behind the Russian lines. The Russians tried to push the Poles back from that position, but ultimately failed. Their assault on the village of Wiktorów also ended in failure. Soon the Polish positions in Mokre were secured, and further reinforced with the remainder of the 1st Battalion, 28th Regiment.[38]

With the northern flank safely in Polish hands, General Lucjan Żeligowski ordered his Lithuanian-Belarusian Division to complete the encirclement of Radzymin. The division reached a position a few hundred metres from Radzymin by way of the village of Ciemne to the south of the town. Fearing envelopment, the Soviets abandoned the town and withdrew east. A single company from the 30th Kaniów Rifles Regiment entered Radzymin unopposed.[33] The town was completely empty; both the civilians and the Russian soldiers had fled, and one officer remarked that "not a stray dog was left behind in the ruined city".[38]

Aftermath: August 16 and the following days

[edit]

Although the battle was over and Radzymin was secure, the Soviet forces continued to threaten the Polish northern flank. In the early hours of August 16, the Russians mounted yet another assault on Radzymin, reinforced by several armoured cars and led personally by the commanding officer of the 27th Rifle Division, Vitovt Putna. However, by this time the morale of the 27th Division was already broken, and the assault was easily thwarted by the Polish infantry and the three remaining operational FT tanks. The armoured cars withdrew as soon as the Polish tanks opened fire, and the Russian infantry followed.[52]

Other Russian forces were more successful to the north of the town, where they managed to capture the village of Mokre from the 28th Regiment. The regiment counter-charged the village, but was initially driven off. However, approximately 80 pieces of emplaced Polish artillery laid a 30-minute barrage on the village. It was the greatest concentration of artillery fire in the war up to that point, and had a tremendous effect on the morale of the Russian defenders.[52] After the barrage ended Lieutenant Colonel Wiktor Thommée personally led his forces in a bayonet charge; the regiment re-entered Mokre at noon and the Russians fled.[52]

The entire 13th Red Army stalled because of its defeat at Radzymin.[53] After that success the Poles slowly but steadily pushed the Soviets back beyond the first line of defences that had been overrun several days before. By the end of 16 August, the 28th and 30th Infantry Regiments manned most of the trench line along the Rządza River, near the village of Dybów.[52] Although initially, the Russian command wanted to use the outskirts of Radzymin as a pivot for a tactical withdrawal to the Radzymin–Brześć line, the following day the Soviet commander ordered a full retreat towards Wyszków and later Grodno.[50] Meanwhile, Piłsudski's 4th Army outflanked the surprised Russians and went as far north as the left-wing of Nikolai Sollogub's 16th Red Army, which at that time was constantly pressured from the front by the 10th and 15th divisions.[50] This made existing Russian plans obsolete, and Polish forces started a pursuit that ended with the victorious Battle of the Niemen River in September. On the day of Polish victory, the Soviets issued a propaganda poster in Moscow proclaiming: "Warsaw has fallen. With it the Poland of yesterday became history. It is nothing but a legend now while the truth of today is the red reality. Long live the Soviets! Long live the invincible Red Army!"[52]

Result and assessment

[edit]The battle was a success for the Poles at both the tactical level (the battle of Radzymin itself) and the strategic level (its role in the battle of Warsaw). After several days of constant fighting for the town of Radzymin and its immediate vicinity, the Russian attack was repelled and the Poles were able to mount a successful counteroffensive, forcing the Russian armies out of Poland and in the end destroying them completely.[54]

However, the conduct of the Polish forces and their commanders at Radzymin in the early part of the battle has been criticized by historians since the 1920s.[3] It was noted by General Lucjan Żeligowski that the importance of the northern approach to Warsaw was poorly understood by the Polish commanders prior to the battle and that the untested and relatively weak 10th Division was chosen for the task of defending Radzymin "out of sheer incompetence".[31] In his memoirs he also heavily criticized the commanding officers of the division, whose "military prowess and punctuality in carrying out orders was little more than irony".[31] Other post-war authors argued[38] that on August 13, when the first Russian forces appeared in front of Radzymin, the 1st Army had more than enough time to reinforce the weak Polish forces there.[38] Instead, it took several days to recapture what could have been held from the start.[38]

Despite the lack of strategic flair in the Polish defence of Radzymin, it was one of the cornerstones of the overall success in the Battle of Warsaw.[55] Although it was Piłsudski's Assault Group that defeated the Russians, the forces at Radzymin and Sikorski's 5th Army were responsible for stopping them at the gates of Warsaw.[3][35] Żeligowski noted in his memoirs that "Warsaw was saved thanks to Polish successes at Mokra, Wólka Radzymińska and Radzymin".[24]

The battle in popular culture and the media

[edit]As one of the crucial battles of the war of 1920, the battle for Radzymin has been featured in novels, memoirs and historical monographs. It was also portrayed in the 2011 film Battle of Warsaw 1920, although the battle of Radzymin sequence was shot mostly in Piotrków Trybunalski.[56] Since 1998 a re-enactment of the battle has been held annually on August 15 in Ossów and Radzymin,[57] organized by various re-enactment groups and a local powiat administration.[58]

Notes

[edit]- ^ The division was originally called the Lithuanian-Belarusian Division (Polish: Dywizja Litewsko-Białoruska). In the early summer of 1920 it was renamed the 19th Infantry Division, in line with other Polish units of the time. Soon after the battle, General Piłsudski reversed his decision and the division was renamed to its former name. Soon afterwards it was split into two divisions, the 1st and 2nd Lithuanian-Belarusian Divisions.

- ^ The defeat of the 46th Regiment was considered so great that the entire unit was disgraced. After the battle, it was struck from the registers of the Polish Army, and its remnants were incorporated into the 5th Podhale Rifles Infantry Regiment. Even the number of the original regiment was considered disgraced, and thus the post-war Polish Army had 85 infantry regiments numbered from 1 to 86, with the exception of 46th. As described in Odziemkowski (2000), p. 22.

- ^ The use of Polish tanks in the war of 1920 is further discussed in Michał Piwoszczuk's 1935 monograph on the 1st Tank Regiment.

- ^ The Polish Cipher Section had managed to break Russian codes and cyphers by 1919.[59] In the crucial months of 1920, it was able to decode most if not all Russian radio messages easily. Discussed in Nowik, pp. 25–26.

- ^ Russian rifle brigades were roughly similar in size to Polish regiments, while Russian regiments were, at least nominally, similar in size to Polish battalions.

- ^ Piłsudski claimed in his post-war memoirs that he had hastened his counteroffensive by one day, but then postponed it back to August 16, the day the attack eventually started. Piłsudski, pp. 125–126.

- ^ In their drive for Warsaw, Bolshevik forces did briefly reach Włocławek and Płock, and some cavalry patrols crossed the Vistula near Bobrowniki, but not in sufficient time or numbers to affect the outcome of the battle.

Citations

[edit]- ^ Najczuk, ¶ "Rosjanie dysponowali..."

- ^ Najczuk, ¶ "W dniu 14 sierpnia w godzinach popołudniowych..."

- ^ a b c d Szczepański (2002), pp. 30–38

- ^ a b c d Odziemkowski (1990), p. 56

- ^ a b Wyszczelski (1999), pp. 235–293

- ^ Najczuk, ¶ "Ogólnie należy stwierdzić, że głównym zadaniem przedmościa..."

- ^ a b c Jędrzejewicz & Cisek, p. 112

- ^ a b c Najczuk, ¶ "Ciągły odwrót wojsk polskich spod Kijowa wymuszał..."

- ^ a b Najczuk, ¶ "Pierwsze natarcie rosyjskie z rana 13 sierpnia..."

- ^ a b c Żeligowski, pp. 72–74

- ^ Odziemkowski (1990), p. 55

- ^ a b Szczepański (1990), p. 17

- ^ Kolatorski, p. 12

- ^ Wandycz, p. 116

- ^ a b Królikowski (2002), pp. 31–36

- ^ a b Sikorski, pp. 109–134

- ^ Manteuffel, p. 370

- ^ Pruszyński & Giedroyć, p. 238

- ^ Królikowski (1991), p. 66

- ^ Skaradziński, p. 156

- ^ Kowalski, pp. 98–112

- ^ a b Tarczyński, pp. 141–142

- ^ a b Najczuk, ¶ "Atak na przedmoście warszawskie podjęło..."

- ^ a b c Pruszyński & Giedroyć, pp. 32–36

- ^ Odziemkowski (2000), p. 21

- ^ Gałęzowski, p. 27

- ^ Odziemkowski (2000), p. 24

- ^ a b Suchcitz, p. 59

- ^ a b Skaradziński, pp. 212–216

- ^ Piłsudski, p. 18

- ^ a b c d e f g h Żeligowski, pp. 89–98, 142–143

- ^ Wyszczelski (2006), pp. 255–259

- ^ a b c d e f g Wyszczelski (2008), pp. 17–22

- ^ a b c d e Wierzbicki, pp. 594–595

- ^ a b Fiddick, pp. 196–219

- ^ a b c d Odziemkowski (2000), p. 22

- ^ Pobóg-Malinowski, p. 453

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Skaradziński, pp. 185–192, 215

- ^ Kolatorski, pp. 54–60

- ^ a b D'Abernon, pp. 83, 144

- ^ Davies, p. 213

- ^ Zamoyski, p. 89

- ^ Wyszczelski (2005), pp. 147–148

- ^ Zamoyski, p. 86

- ^ a b c Królikowski (1991), pp. 17–55

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Odziemkowski (2000), p. 23

- ^ Sikorski, p. 13

- ^ Kolatorski, p. 64

- ^ a b Najczuk, ¶ "Dowództwo na całością sił wydzielonych..."

- ^ a b c d Zamoyski, pp. 86–102

- ^ Piłsudski, pp. 134–137

- ^ a b c d e Odziemkowski (2000), p. 25

- ^ Davis, p. 371

- ^ Wyszczelski (2006), p. 10

- ^ Gieleciński, Izdebski et al., p. 104

- ^ Jaczyński, ¶ "W rolę Radzymina wcielił się Piotrków..."

- ^ PAP, ¶ "Inscenizacją Bitwy Warszawskiej 1920 r..."

- ^ AW & PAP, ¶ "Organizatorami rekonstrukcji było Starostwo Powiatowe..."

- ^ Ścieżyński, p. 19

References

[edit]- Articles

- Lt.Col. Ryszard Najczuk (2010-08-16). "Bitwa pod Radzyminem (13–15 VIII 1920 r.)" [Battle of Radzymin (13–15 of August 1920)]. wojsko-polskie.pl (in Polish). Polish Army. Archived from the original on 2012-04-03. Retrieved 2011-10-29.

- Janusz Odziemkowski (2000). Janusz Kuligowski; Krzysztof Szczypiorski (eds.). "Walki na przedmościu warszawskim i ofensywa znad Wieprza 1920 roku" [Fights for the Warsaw bridgehead and the Wieprz River offensive of 1920] (PDF). Rocznik Mińsko-Mazowiecki (in Polish). 6. Mińsk Mazowiecki: Towarzystwo Przyjaciół Mińska Mazowieckiego: 17–28. ISSN 1232-633X. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-04-25. Retrieved 2011-10-24.

- Janusz Szczepański (2002). "Kontrowersje Wokół Bitwy Warszanskiej 1920 Roku" [Controversies surrounding the Battle of Warsaw in 1920]. Mówią Wieki (in Polish) (8): 30–38. Archived from the original on 2011-07-18. Retrieved 2011-10-04.

- Books

- Edgar Vincent D'Abernon (1977). The Eighteenth Decisive Battle of the World: Warsaw, 1920. Hyperion Press. p. 178. ISBN 0-88355-429-1.

- Norman Davies (1981). God's Playground. Vol. 2. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 672. ISBN 978-0-19-822592-8.

- Paul K. Davis (2001). 100 decisive battles: from ancient times to the present. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 480. ISBN 978-0-19-514366-9.

- Thomas C. Fiddick (1990). Russia's retreat from Poland, 1920: from permanent revolution to peaceful coexistence. Vol. 2. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 196–219. ISBN 978-0-312-03998-1.

- Marek Gałęzowski (2011). Andrzej Dusiewicz (ed.). Bitwa Warszawska 1920 [Battle of Warsaw 1920] (PDF) (in Polish). Warsaw: Nowa Era. p. 39. ISBN 978-83-267-0322-5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-12-08. Retrieved 2011-11-10.

- Marek Gieleciński; Jerzy Izdebski; Zofia Krasicka; Uniwersytet Warszawski. Instytut Historyczny (1996). "Bój o Radzymin" [Battle for Radzymin]. In Józef Ryszard Szaflik; Arkadiusz Kołodziejczyk (eds.). Wieś, chłopi, ruch ludowy, państwo [The Village, The Popular Movements, the State] (in Polish). Warsaw: Warsaw University Press. p. 104.

- Wacław Jędrzejewicz; Janusz Cisek (1998). Kalendarium życia Józefa Piłsudskiego 1867–1935 [Chronological biography of Józef Piłsudski] (in Polish). Vol. II. Warsaw: LTW. ISBN 978-83-88736-92-6.

- Władysław Kolatorski; Jan Wnuk (1995). Bitwa pod Radzyminem w 1920 roku [Battle at Radzymin in 1920] (in Polish). Warsaw: Volumen. p. 107. ISBN 83-902669-1-1.

- Tadeusz Kowalski; Janusz Szczepański (1996). Adam Dobroński (ed.). Dzieje 13 pułku piechoty [History of the 13th Infantry Regiment] (in Polish). preface by Adam Koseski. Pułtusk: Wyższa Szkoła Humanistyczna w Pułtusku, USKOR. p. 329. ISBN 83-906458-1-5.

- Lech Królikowski (1991). Bitwa warszawska 1920 roku; działania wojenne, zachowane pamiątki [Battle of Warsaw of 1920; armed actions, surviving sites] (in Polish). Warsaw: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe. pp. 17–55. ISBN 83-01-10316-7.

- Lech Królikowski (2002). Twierdza Warszawa [Warsaw Fortress] (in Polish). Warsaw: Bellona. p. 383. ISBN 83-11-09356-3.

- Various authors; Tadeusz Manteuffel (1966). Tadeusz Manteuffel; Andrzej Ajnenkiel; Stanisław Arnold (eds.). Historia Polski [History of Poland] (in Polish). Vol. 4. Warsaw: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe. p. 525. PB 3944/66.

- Grzegorz Nowik (2004). Zanim złamano Enigmę...; polski radiowywiad podczas wojny z bolszewicką Rosją 1918–1920 [Before Enigma Was Broken: Polish Radio Intelligence during the War with Bolshevik Russia, 1918–1920] (in Polish). Warsaw: Rytm. p. 1054. ISBN 83-7399-099-2. Excerpt published as: Grzegorz Nowik (2005-08-13). "Szyfrołamacze" [Code-breakers]. Polityka. 32 (2516): 68–70. ISSN 0032-3500. OCLC 6547308. Archived from the original on 2012-04-30. Retrieved 2011-11-10.

- Janusz Odziemkowski (1990). Bitwa Warszawska 1920 roku [Battle of Warsaw of 1920] (in Polish). Warsaw: Mazowiecki Ośrodek Badań Naukowych im Stanisława Herbsta. p. 56.

- Józef Piłsudski (1937). Julian Stachiewicz, Władysław Pobóg-Malinowski (ed.). Rok 1920 [Year 1920]. Pisma zbiorowe (in Polish). Vol. VII. Warsaw: Instytut Józefa Piłsudskiego. p. 217. 2nd edition: Józef Piłsudski (1990) [1937]. "VIII". In Julian Stachiewicz; Władysław Pobóg-Malinowski (eds.). Rok 1920 [Year 1920]. Pisma zbiorowe. Vol. VII. Józef Moszczeński (preface) (reprint ed.). Warsaw: Krajowa Agencja Wydawnicza. p. 217. ISBN 83-03-03056-6.

- Lt.Col. Michał Piwoszczuk (1964) [1935]. Zarys historii wojennej 1 pułku czołgów [Concise wartime history of the 1st Tank Regiment] (in Polish) (2 ed.). London: Taurus. p. 135. OCLC 27102801.

- Władysław Pobóg-Malinowski (1990). Najnowsza historia polityczna Polski [Modern political history of Poland] (in Polish). Vol. II. Gdańsk: Graf. p. 453.

- Mieczysław Pruszyński; Jerzy Giedroyć (1995). Wojna 1920: dramat Piłsudskiego [War of 1920; Piłsudski's drama] (in Polish). Warsaw: BGW. pp. 32–36, 157, 190–196. ISBN 83-7066-560-8.

- Władysław Sikorski (1928). Nad Wisłą i Wkrą; studjum z polsko-rosyjskiej wojny 1920 roku [By the Vistula and Wkra Rivers; study on the Polish-Russian war of 1920] (in Polish). Vol. 1. Lwów: Ossolineum. pp. 13, 109–134.

- Bohdan Skaradziński (1993). Polskie lata 1919–1920 [Polish years 1919–1920] (in Polish). Vol. 2. Warsaw: Volumen. pp. 185–192, 215. ISBN 978-83-85218-47-0.

- Andrzej Suchcitz (1993). "Putna, Witold". Generałowie wojny polsko-sowieckiej, 1919–1920 (in Polish). Białystok: Muzeum Wojska w Białymstoku. p. 59.

- Janusz Szczepański (1990). Wojna 1920 roku w powiecie Pułtuskim [War of 1920 in the powiat of Pułtusk] (in Polish). Pułtusk: Stacja Naukowa MOBN w Pułtusku. OL 18742942M.

- Col. Mieczysław Ścieżyński (1928). Radjotelegrafja jako źródło wiadomości o nieprzyjacielu [Radiotelegraphy as a Source of Intelligence on the Enemy] (in Polish). Przemyśl: Dowództwo Okręgu Korpusu X. p. 49.

- Various authors (1996). Marek Tarczyński (ed.). Bitwa warszawska 13–28 VIII 1920; dokumenty operacyjne [Battle of Warsaw of August 13–28th, 1920; operational documents] (in Polish). Vol. 2. Warsaw: Rytm. p. 935. ISBN 83-86678-37-2.

- Piotr S. Wandycz (1974). The Lands of Partitioned Poland, 1795–1918. A History of East Central Europe. Vol. 7. Washington: University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-95358-8.

- Andrzej Wierzbicki (1957). Wspomnienia i dokumenty, 1877–1920 [Memories and documents; 1877–1920] (in Polish). Warsaw: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe. pp. 594–595.

- Lech Wyszczelski (1999). Kijów 1920 [Kiev 1920] (in Polish). Warsaw: Bellona. ISBN 83-11-08963-9.

- Lech Wyszczelski (2005). Warszawa 1920 [Warsaw 1920] (in Polish). Warsaw: Bellona. pp. 147–148. ISBN 83-11-10227-9.

- Lech Wyszczelski (2006). Operacja warszawska; sierpień 1920 [Warsaw Operation, August 1920] (in Polish). Warsaw: Bellona. p. 534. ISBN 83-11-10179-5.

- Lech Wyszczelski (2008). Niemen 1920 [Neman 1920] (in Polish). Warsaw: Bellona. pp. 17–22. ISBN 978-83-11-11324-4.

- Adam Zamoyski (2008). Warsaw 1920: Lenin's failed conquest of Europe. HarperPress. pp. 86–102. ISBN 978-0-00-725786-7.

- Lucjan Żeligowski (2005). Wojna w roku 1920 [War of 1920] (in Polish). Warsaw: De Facto. pp. 89–98, 142–143. ISBN 83-89667-49-5.

- News

- AW; PAP (2011-08-14). "Żywa lekcja historii – inscenizacja Bitwy Warszawskiej 1920 r. w Ossowie" [Lesson of live history – reenactment of the Battle of Warsaw in Ossów]. Dziennik Gazeta Prawna (in Polish). Warsaw: INFOR PL. ISSN 2080-6744.

- Grzegorz Jaczyński (2010-07-24). "Bitwa Warszawska 1920 roku – walki o Radzymin w Piotrkowie Trybunalskim" [Battle of Warsaw 1920 – fights for Radzymin in Piotrków Trybunalski]. dobroni.pl (in Polish). Warsaw: Fundacja Wojskowości Polskiej. Archived from the original on 2010-10-30. Retrieved 24 November 2011.

- PAP (1998-08-13). "Inscenizacja Bitwy Warszawskiej" [Battle of Warsaw Re-enactment]. Gazeta Wyborcza (in Polish) (189). Warsaw: Agora: 3. ISSN 0860-908X.

External links

[edit]- Wojciech Zalewski, ed. (2005). "Warszawa (Wołomin) 1920". taktykaistrategia.pl (in Polish). Taktyka i Strategia.

- Renault FT-17 in the Polish service Archived 2018-05-12 at the Wayback Machine

- Władysław Kolatorski. "Bitwa Warszawska" [Battle of Warsaw]. radzymin.pl (in Polish). Urząd Miasta Radzymin. Archived from the original on 2012-04-25. Retrieved 2011-10-06.

- Gallery of historical pictures of the battle Archived 2012-04-25 at the Wayback Machine

- Gallery of stills from the 2011 film featuring the battle

- 1915/1922 staff map of Radzymin and its surroundings