Submarine warfare

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in German. (September 2023) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

| Part of a series on |

| War (outline) |

|---|

|

Submarine warfare is one of the four divisions of underwater warfare, the others being anti-submarine warfare, mine warfare and mine countermeasures.

Submarine warfare consists primarily of diesel and nuclear submarines using torpedoes, missiles or nuclear weapons, as well as advanced sensing equipment, to attack other submarines, ships, or land targets. Submarines may also be used for reconnaissance and landing of special forces as well as deterrence. In some navies they may be used for task force screening. The effectiveness of submarine warfare partly depends on the anti-submarine warfare carried out in response.

American Revolution

[edit]The first attack by a submarine occurred on September 8, 1776, by the American submarine Turtle in an unsuccessful attack on the British warship Eagle.

American Civil War

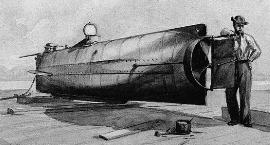

[edit]The age of submarine warfare began during the American Civil War. The 1860s was a time of many turning points in terms of how naval warfare was fought. Many new types of warships were being developed for use in the United States and Confederate States Navies. Submarine watercraft were among the newly created vessels. The first sinking of an enemy ship by a submarine occurred on 17 February 1864, when the Confederate submarine H. L. Hunley, a privateer, sank the sloop USS Housatonic in Charleston Harbor, South Carolina. Shortly afterward, however, H. L. Hunley sank, with the loss of her entire crew of eight.

World War I

[edit]

Submarine warfare in World War I was primarily a fight between German and Austro-Hungarian U-boats and merchant vessels bound for the United Kingdom, France, and Russia. British and Allied submarines conducted widespread operations in the Baltic, North, Mediterranean and Black Seas along with the Atlantic Ocean. Only a few actions occurred outside the wider European-Atlantic theatre.

The first round of major German submarine attacks on Allied merchant ships began in February 1915, but American civilian deaths, especially with the sinking of Lusitania, turned American public opinion against the Central Powers. The U.S. demanded it stop, and Germany conducted submarine attacks under prize rules from September 1915 to January 1917. Admiral Henning von Holtzendorff (1853–1919), chief of the admiralty staff, argued successfully in December 1916 to resume unrestricted attacks from February 1917 and thus starve the British. The German high command realized the resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare, now to include deliberate attacks on neutral shipping, meant war with the United States but calculated that American mobilization would be too slow to stop a German victory on the Western Front[1][2] and played a large role in the United States entering the war in April 1917. Once naval convoys were implemented, sinkings did not reach the German Imperial Admiralty Staff's optimistic projections.[3]

The sinking of HMS Pathfinder was the first combat victory of a modern submarine,[4] and the exploits of SM U-9, which sank three British cruisers in under an hour, established the submarine as an important new component of naval warfare.[5] During World War I more than 5,000 Allied ships were sunk by U-boats.[6]

German submarines were used to lay naval mines and to attack iron ore shipping in the Baltic. The British submarine flotilla in the Baltic operated in support of the Russians until the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. During the war, the British invested efforts into developing a submarine that could operate in conjunction with a battleship fleet – the "Fleet Submarine". To achieve the necessary 20 knots (37 km/h) (surfaced) the K-class submarines were steam powered. In practice, the K class were a constant problem and could not operate effectively with a fleet.

Interwar period

[edit]Between the wars, navies experimented with submarine cruisers (France, Surcouf), submarines armed with battleship caliber guns (UK, HMS M1) and submarines capable of carrying small aircraft for reconnaissance (HMS M2 and Surcouf).

Germany was denied submarines by the terms of the Treaty of Versailles, but built some anyway. This was not legitimized until the Anglo-German Naval Agreement of 1935, under which the UK accepted German parity in submarine numbers with the Royal Navy.

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (June 2008) |

World War II

[edit]In World War II, submarine warfare was split into two main areas – the Atlantic and the Pacific. The Mediterranean Sea was also a very active area for submarine operations. This was particularly true for the British and French, as well as the Germans. The Italians were also involved, but achieved their greatest successes using midget submarines and human torpedoes.

Atlantic Ocean

[edit]

In the Atlantic, where German submarines again sought out and attacked Allied convoys, this part of the war was very reminiscent of the latter part of World War I. Many British submarines were active as well, particularly in the Mediterranean and off Norway, against Axis warships, submarines and merchant shipping.

Initially, Hitler ordered his submarines to abide by the prize rules, but this restriction was withdrawn in December 1939. Although mass attacks by submarine had been carried out in World War I, the "wolf pack" was mainly a tactic of World War II U-boats. The main steps in this tactic were as follows:

- A number of U-boats were dispersed across possible paths of a convoy.

- A boat sighting a convoy would signal its course, speed and composition to German Naval Command.

- The submarine would continue to shadow the convoy, reporting any changes of course.

- The rest of the pack would then head to the first boat's position.

- When the pack was formed, a coordinated attack would be made on the surface at night.

- At dawn, the pack would withdraw, leaving a shadower, and resume the attack at dusk.

With the later increase in warship and aircraft escorts, U-boat losses became unacceptable. Many boats were lost, and the earlier experienced commanders with them.

Almost 3,000 Allied ships (175 warships, 2,825 merchantmen) had been sunk by U-boats.[7] Germany's U-boat fleet suffered heavy casualties, losing 793 U-boats and about 28,000 submariners out of 41,000, a casualty rate of about 70%.[8]

Pacific Ocean

[edit]In the Pacific, the situation was reversed, with US submarines hunting Japanese shipping. By war's end, US submarines had destroyed over half of all Japanese merchant ships,[9] totaling well over five million tons of shipping.[9] British and Dutch submarines also took part in attacks on Japanese shipping, mostly in coastal waters. Japanese submarines were initially successful, destroying two US fleet aircraft carriers, a cruiser, and several other ships. However, following a doctrine that concentrated on attacking warships, rather than more-vulnerable merchantmen, the smaller Japanese fleet proved ineffectual in the long term, while suffering heavy losses to Allied anti-submarine measures. Italian submarines and one German submarine[10] operated in the Pacific Ocean, but never enough to be an important factor, inhibited by distance and difficult relations with their Japanese ally.

Other areas

[edit]Mediterranean Sea

[edit]Indian Ocean

[edit]Japanese submarines operated in the Indian Ocean, forcing the British surface fleet to withdraw to the east coast of Africa. Some German and Italian submarines operated in the Indian Ocean, but never enough to play a significant role.[10]

Post-World War II

[edit]Since the Second World War, several wars, such as the Korean War, Indo-Pakistani War of 1971 and the Falklands War, have involved limited use of submarines. Later submarine-launched land-attack missiles were employed against Iraq and Afghanistan. With these exceptions, submarine warfare ceased after 1945. Hence strategic thinking about the role of submarines has developed independently of actual experience.

The advent of the nuclear-powered submarine in the 1950s brought about a major change in strategic thinking about submarine warfare. These boats could operate faster, deeper and had much longer endurance. Their larger sizes also allowed them to become missile launching platforms. Nuclear power would allow submarines to have greater accuracy and the ability to use torpedoes against ships, other submarines, and land targets.[11] In response to this the attack submarine became more important, particularly in regard to its postulated role as a hunter-killer. The US also used nuclear submarines as radar pickets for a while. There have also been major advances in sensors and weapons.

During the Cold War, the United States and the Soviet Union played what was described as a 'cat-and-mouse' game of detecting and even trailing enemy submarines.

As the likelihood of unrestricted submarine warfare has diminished, thinking about conventional submarines has focused on their use against surface warships. The mere existence of a submarine may curtail surface warships' freedom to operate. To counter the threat of these submarines, hunter submarines were developed in turn. The role of the submarine has extended with the use of submarine-launched autonomous unmanned vehicles.[citation needed] The development of new air independent propulsion methods has meant that the diesel-electric submarine's need to surface, making it vulnerable, has been reduced. Nuclear submarines, although far larger, could generate their own air and water for an extended duration, meaning their need to surface was limited in any case.

In today's more fractured geopolitical system, many nations are building and/or upgrading their submarines.[citation needed] The Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force has launched new models of submarines every few years;[citation needed] South Korea has upgraded the already capable Type 209(Chang Bogo class) design from Germany and sold copies to Indonesia.[12][13] Russia has improved the old Soviet Kilo model into what strategic analysts are calling equivalent to the 1980s-era Los Angeles class, and so on.[citation needed]

At the end of his naval warfare book The Price of Admiralty, military historian John Keegan postulates that eventually, almost all roles of surface warships will be taken over by submarines, as they will be the only naval units capable of evading the increasing intelligence capabilities (space satellites, airplanes etc.) that a fight between evenly matched modern states could bring to bear on them.[citation needed]

However, thinking about importance of the submarine has shifted to an even more strategic role, with the advent of the nuclear ballistic missile submarine carrying Submarine-launched ballistic missiles with nuclear weapons to provide second strike capability.

Modern submarine missions

[edit]A modern submarine is a multi-role platform. It can conduct both overt and covert operations. In peacetime it can act as a deterrent as well as for surveillance operations and information gathering.

In wartime a submarine can carry out a number of missions including:

- Surveillance and information gathering

- Communication of data

- Landing of special operations forces

- Attack of land targets (first cruise missile fired from sub, Gulf War, USS Louisville, Jan 1991)[14]

- Protection of task forces and merchant shipping

- Denial of sea areas to an enemy

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Dirk Steffen, "The Holtzendorff Memorandum of 22 December 1916 and Germany's Declaration of Unrestricted U-boat Warfare." Journal of Military History 68.1 (2004): 215–224. excerpt

- ^ See The Holtzendorff Memo (English translation) with notes

- ^ Tucker, Spencer; Roberts, Priscilla Mary (2014) [2005], Daniel Ramos (ed.), World War I: Encyclopedia, United States: ABC-CLIO, p. 312, ISBN 9781851094202

- ^ Story of the U-21, National Underwater and Marine Agency, archived from the original on 27 December 2008, retrieved 2 November 2008

- ^ Helgason, Guðmundur. "WWI U-boats: U 9". German and Austrian U-boats of World War I - Kaiserliche Marine - Uboat.net. Retrieved 2 November 2008.

- ^ Roger Chickering, Stig Förster, Bernd Greiner, German Historical Institute (Washington, D.C.) (2005). "A world at total war: global conflict and the politics of destruction, 1937–1945". Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-83432-2, p. 73

- ^ Crocker III, H. W. (2006). Don't Tread on Me. New York: Crown Forum. p. 310. ISBN 978-1-4000-5363-6.

- ^ "The Battle of the Atlantic: The U-boat peril". BBC. 30 March 2011.

- ^ a b Blair, Clay, Jr. Silent Victory (New York, 1976), p. 878.

- ^ a b Klemen, L (1999–2000). "The U-Boat War in the Indian Ocean". Forgotten Campaign: The Dutch East Indies Campaign 1941–1942. Archived from the original on 21 March 2011.

- ^ Vergun, David (16 March 2020). "Submarine Warfare Played Major Role in World War II Victory". US Department of Defense. Archived from the original on 24 October 2021. Retrieved 24 October 2021.

- ^ "Forget North Korea's Subs: South Korea Can Build Some Amazing Attack Submarines". 7 August 2017.

- ^ "Brand new South Korean-made submarine joins Indonesian Navy".

- ^ "BGM-109 Tomahawk – Operational Use". www.globalsecurity.org.

References

[edit]- Blair, Clay. Silent Victory: The U. S. Submarine War Against Japan 2 vol (1975)

- L, Klemen (2000). "Forgotten Campaign: The Dutch East Indies Campaign 1941–1942". Archived from the original on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 30 March 2021.

Further reading

[edit]- John Abbatiello. Anti-Submarine Warfare in World War I: British Naval Aviation and the Defeat of the U-Boats (2005)

- Gray, Edwyn A. The U-Boat War, 1914–1918 (1994)

- Hackmann, Willem. Seek & Strike: Sonar, anti-submarine warfare and the Royal Navy 1914–54. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 1984. ISBN 0-11-290423-8

- Lance, Rachel (2024). Chamber Divers: The Untold Story of the D-Day Scientists Who Changed Special Operations Forever. Dutton. ISBN 978-0593184936.

- Preston, Antony. The World's Greatest Submarines (2005).

- Roscoe, Theodore. United States Submarine Operations in World War II (US Naval Institute, 1949).

- van der Vat, Dan. The Atlantic Campaign Harper & Row, 1988. Connects submarine and antisubmarine operations between World War I and World War II, and suggests a continuous war.

External links

[edit]- Historic films showing submarine warfare during World War I at europeanfilmgateway.eu