McGill University

| |

Other name | Université McGill (French) |

|---|---|

Former name | McGill College or University of McGill College (1821–1885) |

| Motto |

|

Motto in English |

|

| Type | Public research university |

| Established | March 31, 1821[2] |

| Founder | James McGill |

Academic affiliation | AAU, ACU, AUCC, AUF, ATS, CARL, CBIE, BCI, CUSID, GULF, UArctic, UNAI, U15, URA |

| Endowment | CA$2.109 billion[3] |

| Budget | CA$1.555 billion[4] |

| Chair | Maryse Bertrand |

| Chancellor | Pierre Boivin |

| President | H. Deep Saini[5][6] |

| Visitor | Mary Simon (as Governor General of Canada) |

Academic staff | 3,476 (staff) 1,747 tenure track, 1,667 non-tenure track (faculty)[7] |

Administrative staff | 4,327[8] |

| Students | 39,513 (2022)[9] |

| Undergraduates | 27,085 (2022)[9] |

| Postgraduates | 10,344 (2022)[9] |

Other students | 2,084 (2022)[9] |

| Location | , Canada 45°30′15″N 73°34′29″W / 45.50417°N 73.57472°W |

| Campus |

|

| Language | English |

| Newspapers | The McGill Daily The Tribune |

| Colours | McGill Red and White[11] |

| Nickname | McGill Redbirds and Martlets |

Sporting affiliations | |

| Mascot | Marty the Martlet |

| Website | www |

| |

McGill University (French: Université McGill) is an English-language public research University located in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. Founded in 1821 by royal charter,[12] the university bears the name of James McGill, a Scottish merchant,[13] whose bequest in 1813 established the University of McGill College. In 1885, the name was officially changed to McGill University.

Currently, McGill has an enrollment of close to 35,000 students. Its main campus is on the slope of Mount Royal in downtown Montreal in the borough of Ville-Marie, with a second campus situated in Sainte-Anne-de-Bellevue, 30 kilometres (19 mi) west of the main campus on Montreal Island. The university is one of two members of the Association of American Universities located outside the United States,[14] alongside the University of Toronto, and is the only Canadian member of the Global University Leaders Forum (GULF) within the World Economic Forum.[15] The university offers degrees and diplomas in over 300 fields of study. Most students are enrolled in the six largest faculties: Arts, Science, Medicine, Education, Engineering, and Management.[16]

McGill alumni, faculty, and affiliates include 12 Nobel laureates[17] and 149 Rhodes Scholars,[18] the current prime minister and two former prime ministers of Canada, and two Governors General of Canada. McGill alumni also include 9 Academy Award winners,[note 1] 13 Grammy Award winners,[note 2] 15 Emmy Award winners,[note 3] four Pulitzer Prize winners,[note 4] and 121 Olympians with over 35 Olympic medals.[21]

History

Royal Institution for the Advancement of Learning

The Royal Institution for the Advancement of Learning (RIAL) was created in 1801 under an Act of the Legislative Assembly of Lower Canada (41 George III Chapter 17), An Act for the establishment of Free Schools and the Advancement of Learning in this Province.[22] The RIAL was initially authorized to operate two new Royal Grammar Schools, in Quebec City and in Montreal. This was a turning point for public education in Lower Canada as the schools were created by legislation, which showed the government's willingness to support the costs of education and even the salary of a schoolmaster. This was an important first step in the creation of non-denominational schools. When James McGill died in 1813, his bequest was administered by the RIAL.

In 1846 the Royal Grammar School in Quebec City closed, and the one in Montreal merged with the High School of Montreal. By the mid-19th century, the RIAL had lost control of the other eighty-two grammar schools it had administered.[23] However, in 1853 it took over the High School of Montreal from the school's board of directors and continued to operate it until 1870.[24][25] Thereafter, its sole remaining purpose was to administer the McGill bequest on behalf of the private college. The RIAL continues to exist today; it is the corporate identity that runs the university and its various constituent bodies, including the former Macdonald College (now Macdonald Campus), the Montreal Neurological Institute, and the Royal Victoria College (the former women's college turned residence). Since the revised Royal Charter of 1852, the trustees of the RIAL are the board of governors of McGill University.[12]

McGill College

James McGill was born in Glasgow, Scotland, on October 6, 1744. He was a successful merchant in Quebec, having matriculated into the University of Glasgow in 1756.[26][27] Soon afterwards, McGill left for North America to explore the business opportunities there, especially in the fur trade. McGill was also a slave owner, and the McGill household enslaved at least five Black and Indigenous people.[28] Between 1811 and 1813,[29] he drew up a will leaving his "Burnside estate", a 19-hectare (47-acre) tract of rural land and 10,000 pounds to the Royal Institution for the Advancement of Learning.[30][31][32]

As a condition of the bequest, the land and funds had to be used for the establishment of a "University or College, for the purposes of Education and the Advancement of Learning in the said Province."[2] The will specified a private, constituent college[12] bearing his name would have to be established within ten years of his death; otherwise, the bequest would revert to the heirs of his wife.[33]

On March 31, 1821, after protracted legal battles with the Desrivières family (the heirs of his wife), McGill College received a royal charter from King George IV. The charter provided the college should be deemed and taken as a University, with the power of conferring degrees.[2] The third Lord Bishop of Quebec, The Right Reverend George Mountain, (DCL, Oxford) was appointed the first principal of McGill College and a professor of divinity. He is also responsible for the creation of Bishop's University in 1843 and Bishop's College School in 1836 in the Eastern Townships.[34]

University development

Campus expansions

Although McGill College received its Royal Charter in 1821, it was inactive until 1829 when the Montreal Medical Institution, which had been founded in 1823, became the college's first academic unit and Canada's first medical school. The Faculty of Medicine granted its first degree, a Doctorate of Medicine and Surgery, in 1833; this was also the first medical degree to be awarded in Canada.[35]

The Faculty of Medicine remained the school's only functioning faculty until 1843 when the Faculty of Arts commenced teaching in the newly constructed Arts Building and East Wing (Dawson Hall).[36]

The Faculty of Law was founded in 1848 and is also the oldest of its kind in the nation. In 1896, the McGill School of Architecture was the second architecture school to be established in Canada, six years after the University of Toronto in 1890.[37] Sir John William Dawson, McGill's principal from 1855 to 1893, is often credited with transforming the school into a modern University.[38]

William Spier designed the addition of the West Wing of the Arts Building for William Molson, 1861.[39] Alexander Francis Dunlop designed major alterations to the East Wing of McGill College (now called the Arts Building, McGill University) for Prof. Bovey and the Science Dept., 1888.[40] George Allan Ross designed the Pathology Building, 1922–23; the Neurological Institute, 1933; Neurological Institute addition 1938 at McGill University.[41] Jean Julien Perrault (architect) designed the McTavish Street residence for Charles E. Gravel, which is now called David Thompson House (1934).[42]

Women's education

Women's education at McGill began in 1884 when Donald Smith (later the Lord Strathcona and Mount Royal), began funding separate lectures for women, given by University staff members. The first degrees granted to women at McGill were conferred in 1888.[43] In 1899, the Royal Victoria College (RVC) opened as a residential college for women at McGill with Hilda D. Oakeley as the head. Until the 1970s, all female undergraduate students, known as "Donaldas," were considered to be members of RVC.[44] Beginning in the autumn of 2010, the newer Tower section of Royal Victoria College became a mixed gender dormitory, whereas the older West Wing remains strictly for women. Both the Tower and the West Wing of Royal Victoria College form part of the university's residence system.[45]

McGill in the Great War

Many students and alumni enlisted in the first wave of patriotic fervour that swept the nation in 1914 at the outbreak of World War I, but in the spring of 1915—after the first wave of heavy Canadian casualties at Ypres—Hamilton Gault, the founder of the Canadian regiment and a wealthy Montreal businessman, was faced with a desperate shortage of troops. When he reached out to his friends at home for support, over two hundred were commissioned from the ranks, and many more would serve as soldiers throughout the war. On their return to Canada after the war, Major George McDonald and Major George Currie formed the accounting firm McDonald Currie, which later became one of the founders of Price Waterhouse Coopers.[46] Captain Percival Molson was killed in action in July 1917. Percival Molson Memorial Stadium at McGill is named in his honour.

The War Memorial Hall (more generally known as Memorial Hall) is a landmark building on the campus of McGill University. At the dedication ceremony, the Governor General of Canada (Harold Alexander, 1st Earl Alexander of Tunis) laid the cornerstone. Dedicated on October 6, 1946, the Memorial Hall and adjoining Memorial Pool honour students who had enlisted and died in the First World War, and in the Second World War. In Memorial Hall, there are two Stained Glass Regimental badges, World War I and World War II Memorial Windows by Charles William Kelsey c. 1950/1.[47]

A war memorial window (1950) by Charles William Kelsey in the McGill War Memorial Hall depicts the figure of St. Michael and the badges of the Navy, Army and the Air Force. A Great War memorial window featuring Saint George and a slain dragon at the entrance to the Blackader-Lauterman Library of Architecture and Art is dedicated to the memory of 23 members of the McGill chapter of Delta Upsilon who gave their lives in the Great War.[48]

There is a memorial archway at Macdonald Campus, two additional floors added to the existing Sir Arthur Currie gymnasium, a hockey rink and funding for an annual Memorial Assembly. A Book of Remembrance on a marble table contains the names of those lost in both World Wars. On November 11, 2012, the McGill Remembers website launched; the University War Records Office collected documents between 1940 and 1946 related to McGill students, staff and faculty in the Second World War.[49]

Founder of universities and colleges

McGill was instrumental in founding several major universities and colleges. It established the first post-secondary institutions in British Columbia to provide degree programs to the growing cities of Vancouver and Victoria. It chartered Victoria College in 1903 as an affiliated junior college of McGill, offering first and second-year courses in arts and science, until it became today's University of Victoria. British Columbia's first University was incorporated in Vancouver in 1908 as the McGill University College of British Columbia. The private institution granted McGill degrees until it became the independent University of British Columbia in 1915.[50]

Dawson College began in 1945 as a satellite campus of McGill to absorb the anticipated influx of students after World War II. Many students in their first three years in the Faculty of Engineering took courses at Dawson College to relieve the McGill campus for the later two years for their degree course. Dawson eventually became independent of McGill and evolved into the first English CEGEP in Quebec. Another CEGEP, John Abbott College, was established in 1971 at the campus of McGill's Macdonald College.[51]

Both founders of the University of Alberta, Premier Alexander Cameron Rutherford of Alberta and Henry Marshall Tory, were also McGill alumni. In addition, McGill alumni and professors, Sir William Osler and Howard Atwood Kelly, were among the four founders and early faculty members of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.[52] Osler eventually became the first Physician-in-Chief of the new Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland, US in 1889. He led the creation of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in 1893.[53] Other McGill alumni founded the Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry in the 1880s.[54] By 1961, McGill had an enrolment of 8,507 students and 925 graduate students.[55] Since the 1960s McGill has experienced government funding curtailment.[56] According to a 2016 report, McGill had a $1.3 billion deferred maintenance bill.[57] The report also identified that 73 per cent of the university's buildings were in poor or very poor shape.[58]

Quotas on Jewish students

McGill University, alongside other universities like Sir George Williams University (now part of Concordia University) and the University of Toronto Faculty of Medicine, had longstanding quotas in place from 1920 to the late 1960s on the number of Jews admitted to the respective universities.[59][60][61] The quota limited the Jewish student population in medicine and law to at most 10 per cent.[62] The only Montreal-based universities that did not impose such quotas was the Université de Montréal.[63][64][65]

Controversy

McGill University was the subject of controversy when in January 2023, McGill University's Centre for Human Rights and Legal Pluralism (CHRLP) hosted the event, titled Sex vs. Gender (Identity) Debate In the United Kingdom and the Divorce of LGB from T. It was led by McGill alumnus Robert Wintemute. Transgender activist groups stormed the talk at McGill led by a speaker associated with a group they claimed was "notoriously transphobic and trans-exclusionary." The talk was cancelled shortly after it started.[66]

Campus

Downtown campus

McGill's main campus is located in downtown Montreal at the foot of Mount Royal.[67] Most of its buildings are in a park-like campus (also known as the Lower Campus) north of Sherbrooke Street and south of Pine Avenue between Peel and Aylmer streets. The campus extends west of Peel Street (also known as Upper Campus) for several blocks, starting north of Doctor Penfield; the campus also streches east of University Street, starting north of Pine Avenue, an area that includes McGill's Percival Molson Memorial Stadium and the Montreal Neurological Institute and Hospital. The community immediately east of University Street and south of Pine Avenue is known as Milton-Park, where a large number of students reside. The campus is near the Peel and McGill Metro stations. A major downtown boulevard, McGill College Avenue, leads up to the Roddick Gates, the university's formal entrance. Many of the major University buildings were constructed using local grey limestone, which serves as a unifying element.[68] A number of these buildings are connected by indoor tunnels.[69]

The university's first classes were held in at Burnside Place, James McGill's country home.[32][70] Burnside Place remained the sole educational facility until the 1840s, when the school began construction on its first buildings: the central and east wings of the Arts Building.[71] The rest of the campus was essentially a cow pasture, a situation similar to the few other Canadian universities and early American colleges of the age.[72]

The university's athletic facilities, including Molson Stadium, are on Mount Royal, near the residence halls and the Montreal Neurological Institute. The Gymnasium is named in honour of General Sir Arthur William Currie.[73]

Residence system

McGill's residence system comprises 16 properties providing dormitories, apartments, and hotel-style housing to approximately 3,100 undergraduate students and some graduate students from the downtown and Macdonald campuses.[74][75] Few McGill students live in residence after their first year of undergraduate study, even if they are not from the Montreal area. Most second-year students transition to off-campus apartment housing. Many students settle in the Milton-Park neighbourhood, sometimes called the "McGill Ghetto,"[76] which is the neighbourhood directly to the east of the downtown campus. Students have also moved to areas such as Mile End, The Plateau, and even as far as Verdun because of rising rent prices.[77]

Many first-year students live in the Upper Residence.[78][79] Royal Victoria College opened as a residential college for women in 1899, but its Tower section became mixed gender in September 2010 while its West Wing remains strictly for women.[45] The college's original building was designed by Bruce Price and its extension was designed by Percy Erskine Nobbs and George Taylor Hyde.[80] A statue of Queen Victoria by her daughter Princess Louise, Duchess of Argyll, stands in front of the building.[81]

Macdonald campus

A second campus, the Macdonald Campus, in Sainte-Anne-de-Bellevue houses the Faculty of Agricultural and Environmental Science, the School of Dietetics and Human Nutrition, the Institute of Parasitology, and the McGill School of Environment. As of fall 2020, despite a decrease in enrollment from the previous year's 1,962 students, the campus has a total of 1,892 actively enrolled students, including those studying part-time and full-time, across all available programs. Of the total, 1,212 students are pursuing an undergraduate degree, 374 are pursuing a Masters-level degree, and 248 are pursuing a Doctoral-level degree, respectively. There is a high international student presence, since over 1 in 5 students are from outside Canada. The campus is considered by many to be quieter than the Downtown Montreal campus. The Morgan Arboretum and the J. S. Marshall Radar Observatory are nearby.

The Morgan Arboretum was created in 1945. It is a 2.5-square-kilometre (0.965 sq mi) forested reserve. Its mandated goals are to continue research related to maintaining the health of the Arboretum plantations and woodlands, to develop new programs related to selecting species adapted to developing environmental conditions and to enhance biological diversity in both natural stands and plantations.[82]

Outaouais campus

In 2019, McGill announced the construction of a new campus for its Faculty of Medicine in Gatineau, Quebec, which will allow students from the Outaouais region to complete their undergraduate medical education locally and in French. Medical students began using the new facility in August 2020.[83] The new facility is located above the emergency room at Gatineau Hospital, part of the Centre intégré de santé et de services sociaux (CISSS) de l'Outaouais, in addition to new offices for the associated Family Medicine Unit for residency training.[83] Although the preparatory year for students entering the undergraduate medical education program from CEGEP was initially planned to be offered solely at the McGill downtown campus in Montreal,[83][84] collaboration with the Université du Québec en Outaouais made it possible to offer the program entirely in Gatineau.[85]

McGill University Health Centre redevelopment plan

In 2006, the Quebec government initiated a $1.6 billion LEED redevelopment project for the McGill University Health Centre (MUHC). The project will expand facilities to two separate campuses[86] and consolidate the various hospitals of the MUHC on the site of an old CP rail yard adjacent to the Vendôme Metro station. This site, known as Glen Yards, comprises 170,000 square metres (1,800,000 sq ft) and spans portions of Montreal's Notre-Dame-de-Grâce neighbourhood and the city of Westmount.[87]

The Glen Yards project has been controversial due to local opposition to the project, environmental issues, and the project's cost.[88]

Sustainability

In 2007, McGill premiered its Office of Sustainability and added a second full-time position in this area, the Director of Sustainability in addition to the Sustainability Officer.[89] Recent efforts in implementing its sustainable development plan include the new Life Sciences Centre which was built with LEED-Silver certification and a green roof, as well as an increase in parking rates in January 2008 to fund other sustainability projects.[89] Other student projects include The Flat: Bike Collective, which promotes alternative transportation, and the Farmer's Market, which occurs during the fall harvest.[90]

McGill Community for Lifelong Learning

Founded in 1989, the McGill Community for Lifelong Learning (MCLL) is an educational community for senior learners housed in the McGill School of Continuing Studies. The program was founded by Fiona Clark, then-assistant director of continuing studies at McGill, and drew inspiration from horizontal peer-led programs, including the Harvard Institute for Learning in Retirement.[91] Its educational model[92] is notably different from an instructor-led approach, and tasks seniors exploring educational interest as either study group moderators or participants. The program brings together hundreds of senior members yearly and has acted as a springboard for numerous senior-led initiatives such as social events, educational symposiums, and cultural festivals, including an internationally recognized yearly Bloomsday event on the life and work of author James Joyce.[93]

Other facilities

McGill's Bellairs Research Institute, in Saint James, Barbados 13°10′N 59°35′W / 13.167°N 59.583°W, is Canada's only teaching and research facility in the tropics.[94] The institute has been in use for over 50 years. The university also operates the McGill Arctic Research Station on Axel Heiberg Island, Nunavut, and a Subarctic Research Station in Schefferville, Quebec.

McGill's Gault Nature Reserve (45°32′N 73°10′W / 45.533°N 73.167°W) spans over 10 square kilometres (3.9 sq mi) of forest land, the largest remaining remnant of the primeval forests of the St. Lawrence River Valley.[95] The first scientific studies at the site occurred in 1859. The site has been the site of extensive research activities: "Today there are over 400 scientific articles, 100 graduate theses, more than 50 government reports and about 30 book chapters based on research at Mont St. Hilaire."[96]

In addition to the McGill University Health Centre, McGill has been directly partnered with many teaching hospitals for decades and has a history of collaborating with many hospitals in Montreal. These cooperations allow the university to graduate over 1,000 students in health care each year.[97] McGill's contract-affiliated teaching hospitals include the Montreal Children's Hospital, the Montreal General Hospital, the Montreal Neurological Hospital, the Montreal Chest Institute and the Royal Victoria Hospital which are all now part of the McGill University Health Centre. Other hospitals health care students may use include the Jewish General Hospital, the Douglas Hospital, St. Mary's Hospital Centre, Lachine Hospital, LaSalle Hospital, Lakeshore General Hospital, as well as health care facilities part of the CISSS.[98]

Administration and organization

Structure

The university's academic units are organized into 11 main Faculties and 13 Schools.[99] These include the School of Architecture, the School of Computer Science, the School of Information Studies, the School of Human Nutrition, the Bensadoun School of Retail Management, the Max Bell School of Public Policy, the School of Physical & Occupational Therapy, the Ingram School of Nursing, the School of Social Work, the School of Urban Planning, and the Bieler School of Environment. They also include the Institute of Islamic Studies (established in 1952), which offers graduate courses leading to the M.A. and PhD degrees.

The Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies[100] (GPS) oversees the admission and registration of graduate students (both master's and PhD).

University identity and culture

The McGill coat of arms is derived from an armorial device assumed during his lifetime by the founder of the University, James McGill. It was designed in 1906 by Percy Nobbs, three years into his term as director of the University's School of Architecture.[101] The University's patent of arms was subsequently granted by the Garter King at Arms in 1922, registered in 1956 with Lord Lyon King of Arms in Edinburgh, and in 1992 with the Public Register of Arms, Flags and Badges of Canada. In heraldic terms, the coat of arms is described as follows: "Argent three Martlets Gules, on a chief dancette of the second, an open book proper garnished or bearing the legend In Domino Confido in letters Sable between two crowns of the first. Motto: Grandescunt Aucta Labore." The coat of arms consists of two parts, the shield and the scroll. The university publishes a guide to the use of the university's arms and motto.[102]

The university's symbol is the martlet, stemming from the presence of the mythical bird on the official arms of the university. The university's official colour is scarlet, which figures prominently in the academic dress of McGill University. McGill's motto is Grandescunt Aucta Labore, Latin for "By work, all things increase and grow" (literally, "Things grown great increase by work," that is, things that grow to be great do so by means of work). The official school song is entitled "Hail, Alma Mater."[103]

Exchange and study abroad

McGill maintains ties with more than 160 partner universities where students can study abroad for either one or two semesters.[104] Each year, McGill hosts around 500 incoming exchange students from over 32 countries. The university offers a multitude of activities and events to integrate students into the university's community. McGill is the home to more than 10,000 foreign students who make up of more than 27 per cent of the student population.[105]

Finances

The McGill endowment provides approximately 10 per cent of the school's annual operating revenues.[106] McGill's endowment rests within the top 10 per cent of all North American post-secondary institutions' endowments.[107] As of 2022, the endowment is valued at $2.039 billion,[108] the third-largest endowment among Canadian universities, and remains one of the largest endowments on a per-student basis.[109]

McGill launched the Campaign McGill campaign in October 2007,[110] with the goal of raising over $750 million for the purpose of further "attracting and retaining top talent in Quebec, to increase access to quality education and to further enhance McGill's ability to address critical global problems."[111] The largest goal of any Canadian University fundraising campaign at the time,[111][112] the campaign was officially closed on June 18, 2013, having raised more than $1 billion.[113][114] Campaign McGill has since been surpassed by larger fundraising campaigns, such as the University of British Columbia's $3 billion FORWARD campaign and the University of Toronto's $4 billion Defy Gravity campaign.[115][116] In 2019, McGill launched Made By McGill, a new $2 billion fundraising campaign.[117]

In 2019, McGill received a $200 million donation to fund the creation of the McCall MacBain Scholarships programme, the then-largest single philanthropic gift to a Canadian University, until it was surpassed in 2020 by a $250 million donation by James and Louise Temerty to the University of Toronto.[118][119]

Academics

Admissions

McGill University has an acceptance rate of 38.1 per cent and a graduate acceptance rate of 29.2 per cent, with an enrolment rate of 19 per cent of all applicants.[120][121][122] 22 per cent of all students are enrolled in the Faculty of Arts, McGill's largest academic unit. Of the other larger faculties, the Faculty of Science enrols 15 per cent, the Faculty of Medicine enrols 13 per cent, the School of Continuing Studies enrols 12 per cent, the Faculty of Engineering and the Desautels Faculty of Management enrol about 10 per cent each.[16] The remainder of all students are enrolled in McGill's smaller schools, including the Faculty of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences, Faculty of Dentistry, Faculty of Medicine, Faculty of Education, Faculty of Law, Schulich School of Music, and the Faculty of Religious Studies. Since the 1880s,[123] McGill has been affiliated with three Theological Colleges; the Montreal Diocesan Theological College (Anglican Church of Canada), The Presbyterian College, Montreal (Presbyterian Church in Canada), and United Theological College (United Church of Canada).[124] The university's Faculty of Religious Studies maintains additional affiliations with other theological institutions and organizations, such as the Montreal School of Theology.[125]

Undergraduate

Among Canadian universities, McGill undergraduates have the fifth highest average entering grades among high school and CEGEP students entering from their home province.[126] Among admitted students, the median Quebec CEGEP R-score was 31.9, while the median grade 12 averages for students entering McGill from outside of Quebec ranged between 93.2 per cent and 94.4 per cent (A). For American students, the median SAT scores in the verbal, mathematics, and writing sections were 730, 730, and 730, respectively. The median ACT score was 32.[127]

Law

Due to its bilingual nature, McGill's law school does not require applicants to sit the LSAT, which is only offered in English. For students who submitted LSAT scores in the September 2019 entering class, the median LSAT score was 163 (87.8th percentile) out of a possible 180 points. Of those students who entered with a bachelor's degree, the median GPA was 86 per cent (3.8/4.0), and of those students entering from CEGEP, the average R-score was 34.29.[128]

Medicine

For medical students in the 2024 entering class, of those students who entered with a bachelor's degree, the average GPA was 3.89 out of 4.0, and of those students entering from CEGEP, the average R-score was 35.69.[129] McGill does not require applicants to its medical programme to sit the MCAT if they have an undergraduate degree from a Canadian University.[130]

MBA

In the Desautels Faculty of Management's MBA program, applicants had an average GMAT score of 670 and an average GPA of 3.3.[131] MBA students had an average age of 28, and five years of work experience. 95 per cent of MBA students are bilingual and 60 per cent are trilingual.[132]

Teaching and learning

In the 2007–2008 school year, McGill offered over 340 academic programs in eleven faculties.[133][134] The university also offers over 250 doctoral and master's graduate degree programs. Despite strong increases in University enrolment across North America,[135] McGill has upheld a student-faculty ratio of 16:1.[136][137] There are nearly 1,600 tenured or tenure-track professors teaching at the university.[138]

Tuition fees vary significantly depending on the faculties that aspiring (graduate and undergraduate) students choose as well as their citizenship. For the undergraduate faculty of the arts, tuition fees vary for in-province, out-of-province, and international students, with full-time Quebec students paying around $4,333.10[139] per year, Canadian students from other provinces paying around $9,509.30[139] per year, and international students paying $22,102.57–$41,815.92 per year.[140]

Since 1996, McGill, in accordance with the Quebec Ministry of Education, Recreation and Sports (Ministère de l'Éducation, du Loisir et du Sport or MELS), has had eight categories that qualifies certain international students to be excused from paying international fees. These categories include: students from France and French-speaking Belgium, a quota of students from select countries which have agreements with MELS, which include Algeria, China, and Morocco,[141] students holding diplomatic status, including their dependents, and students enrolled in certain language programs leading to a degree in French.[142] In the 2008–2009 school year, McGill's graduate business program became funded by tuition. It was the last business school in Canada to do so.[143]

For out-of-province first year undergraduate students, a high school average of 95 per cent is required to receive a guaranteed one-year entrance scholarship.[144] For renewal of previously earned scholarships, students generally need to be within the top 10 per cent of their faculty.[145] For in-course scholarships in particular, students must be within the top 5 per cent of their faculty.[146][147]

The university has joined Project Hero, a scholarship program cofounded by General (Ret'd) Rick Hillier for the families of fallen Canadian Forces members.[148] McGill is also partnered with the STEM initiative Schulich Leader Scholarships, awarding an $80,000 scholarship to an incoming engineering student and a $60,000 scholarship to a student pursuing a degree in science/technology/mathematics each year.[149]

Language policy

McGill is one of three English-language universities in Quebec;[150] French is not a requirement to attend.[151] The Faculty of Law does, however, require all students to be 'passively bilingual' since English or French may be used at any time.[152] The majority of students are fluent in at least two languages.[153] In 2021, about 72 percent of McGill students responding to a census conducted by the university said their level of proficiency in French was at least "intermediate".[154] In 2024, the Quebec government introduced a requirement for 80 percent of enrolled students to reach proficiency in French by graduation.[155]

Francophone students, whether from Quebec or overseas, now make up approximately 20 percent of the student body.[156] Although the language of instruction is English, since its founding McGill has allowed students to write their thesis in French, and since 1964 students in all faculties have been able to submit any graded work in either English or French, provided the objective of the class is not to learn a particular language.[157]

In 1969, the nationalist McGill français movement demanded McGill become francophone, pro-nationalist, and pro-worker.[158] The movement was led by Stanley Gray, a political science professor (and possibly unaware of government plans after the 1968 legislation founding the Université du Québec).[159][160] A demonstration was held of 10,000 trade unionists, leftist activists, CEGEP students, and even some McGill students, at the university's Roddick Gates on March 28, 1969. Protesters saw English as the privileged language of commerce. McGill, where Francophones were only three per cent of the students, could be seen as the force maintaining economic control by Anglophones of a predominantly French-speaking province.[161][162] However, the majority of students and faculty opposed such a position.[163][164]

Rankings and reputation

| University rankings | |

|---|---|

| World rankings | |

| ARWU World[165] | 74 |

| QS World[166] | 29 |

| THE World[167] | 45 |

| THE Employability[168] | 29 |

| USNWR World[169] | 56 (tie) |

| Canadian rankings | |

| ARWU National[165] | 3 |

| QS National[166] | 2 |

| THE National[167] | 3 |

| USNWR National[169] | 3 |

| Maclean's Medical/Doctoral[170] | 1 |

McGill ranks first in Canada among medical-doctoral universities in Maclean's Canadian University Rankings 2023.[170] The university has held the top position in the ranking for 19 consecutive years.[171] The Globe and Mail's Canadian University Report 2019 categorized McGill as "above average" for its financial aid, student experience and research, and as "average" for its library resources.[172] Research Infosource ranked McGill second among Canadian universities with medical schools in its 2020 edition of Research Universities of the Year.[173]

Internationally, McGill ranked 30th in the world and second in Canada in the 2023 QS World University Rankings.[166] It also ranked 26th in the world and second in Canada in the 2023 CWUR World University Rankings.[174] It was ranked 49th in the world and third in Canada by the 2023 Times Higher Education World University Rankings.[167] In 2022, the Academic Ranking of World Universities ranked the University 73rd in the world, and third in Canada.[165] In the 2022–23 U.S. News & World Report Best Global University Rankings, McGill was ranked 54th in the world and third in Canada.[169]

In the Global University Employability Ranking 2022, published by Times Higher Education, McGill ranked 29th in the world and second in Canada.[168] Nature ranked McGill 67th in the world and second in Canada among academic institutions for high-impact research in the 2021 edition of Nature Index.[175] According to Wealth-X's 2019 ranking of ultra-high-net-worth (UHNW) alumni — those with US$30 million or more in net worth — McGill ranked 34th in the world and eighth outside the United States.[176]

McGill's MBA program, offered by the Desautels Faculty of Management, has appeared in several rankings. Quacquarelli Symonds, in its Global MBA Rankings 2021, ranked McGill's MBA 59th in the world and second in Canada.[177] The Financial Times, in its 2020 Global MBA ranking, placed the MBA programme 91st in the world and second in Canada.[178] In Bloomberg BusinessWeek's Best Business Schools ranking 2019–2020, Desautels was ranked seventh in Canada.[179]

McGill is a member of the Global University Leaders Forum (GULF),[180] composed of the presidents of 29 of the world's top universities.[181] It is the only Canadian University member of GULF.[15] McGill is also one of only two non-American universities to be a member of the Association of American Universities, an organization of research-intensive universities.[182]

Research

McGill is affiliated with 12 Nobel Laureates, and professors have won major teaching prizes. According to the Association of Universities and Colleges of Canada, "researchers at McGill are affiliated with about 75 major research centres and networks, and are engaged in an extensive array of research partnerships with other universities, government and industry in Quebec and Canada, throughout North America and in dozens of other countries."[183] In 2016, McGill had over $547 million of sponsored research income, the second-highest in Canada,[184] and a research intensity per faculty of $317,600, the third highest among full-service universities in Canada.[185] McGill has one of the largest patent portfolios among Canadian universities.[186] McGill's researchers are supported by the McGill University Library, which comprises 13 branch libraries and holds over 11.5 million items.[187]

Since 1926, McGill has been a member of the Association of American Universities (AAU), an organization of leading research universities in North America. McGill is a founding member of Universitas 21, an international network of leading research-intensive universities that work together to expand their global reach and advance their plans for internationalization. McGill is one of 26 members of the Global University Leaders Forum (GULF), which acts as an intellectual community within the World Economic Forum to advise its leadership on matters relating to higher education and research. It is the only Canadian University member of GULF. McGill is also a member of the U15, a group of prominent research universities within Canada.[188]

McGill-Queen's University Press began as McGill in 1963 and amalgamated with Queen's in 1969. McGill-Queen's University Press focuses on Canadian studies and publishes the Canadian Public Administration Series.[189]

Sir William Osler, Wilder Penfield, Donald Hebb, Donald Ewen Cameron, Brenda Milner, and others made significant discoveries in medicine, neuroscience and psychology while working at McGill, many at the university's Montreal Neurological Institute. The first hormone governing the Immune System (later christened the Cytokine 'Interleukin-2') was discovered at McGill in 1965 by Gordon & McLean.[190]

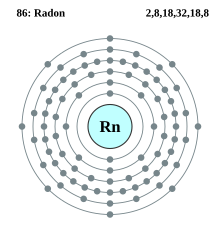

The invention of the world's first artificial cell was made by Thomas Chang while an undergraduate student at the university.[191] While chair of physics at McGill, nuclear physicist Ernest Rutherford performed the experiment that led to the discovery of the alpha particle and its function in radioactive decay, which won him the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1908.[192] Alumnus Jack W. Szostak was awarded the 2009 Nobel Prize in medicine for discovering a key mechanism in the genetic operations of cells, an insight that has inspired new lines of research into cancer.[193]

Libraries, archives and museums

The McGill University Library comprises 12 branch libraries containing 11.5 million items in its collection.[194] Its branches include the Department of Rare Books & Special Collections, which holds about 350,000 items, including books, manuscripts, maps, prints, and a general rare book collection.[195] The Islamic Studies Library contains over 125,000 volumes and a growing number of electronic resources covering the whole of Islamic civilization, including approximately 3,000 rare books and manuscripts.[196] The Osler Library of the History of Medicine is the largest medical history library in Canada and one of the most comprehensive in the world.[197]

The McGill University Archives – now administered as part of the McGill Library – consist of manuscripts, texts, photographs, audio-visual material, architectural records, cartographic materials, prints, drawings, microforms and artifacts.[198] In 1962 F. Cyril James declared that the newly founded McGill University Archives (MUA), while concentrating on the institutional records of McGill, had the mandate to acquire private papers of former faculty members. In the 1990s drew back their acquisition scope, and in 2004, new terms of reference on private acquisitions were introduced that included a wider McGill Community.[199]

The Redpath Museum houses collections of interest to ethnology, biology, paleontology, mineralogy and geology. Built in 1882, the Redpath is the oldest building in Canada built specifically to be a museum.[200]

The McGill Medical Museum catalogues, preserves, conserves and displays collections that document the study and practice of medicine at McGill University and its associated teaching hospitals. The Medical museum features collections, individual specimens, artifacts, equipment logbooks, autopsy journals, paper materials and medical instruments and apparatus, 25 wax models, 200 mostly skeletal dry specimens, and 400 lantern slides of anatomic specimens. There is a special emphasis on pathology; there are 2000 fluid-filled preserved anatomical and pathological specimens. The Osler collection, for example, consists of 60 wet specimens, while The Abbott collection consists of 80 wet specimens, mostly examples of congenital cardiac disease.[201]

Student life

Student body

As of Fall 2021, McGill's student population includes 26,765 undergraduate and 10,411 graduate students representing diverse geographic and linguistic backgrounds. Of the entire student population, 46.8 per cent are from Quebec and 22.8 per cent are from the rest of Canada, while 30.4 per cent are from outside of Canada. International students hail from about 150 countries,[203] with many students coming from the United States, China, and France.[204][205] Over half of McGill students claim a first language other than English, with 19.7 per cent of the students claiming French as their mother tongue and 33.5 per cent claiming a language other than English and French, compared to 46.8 per cent who claim English as their mother tongue.[206] In Fall 2021, 34,379 students were enrolled in full-time studies, while 4,888 students enrolled in part-time studies.[204]

Student organizations

The campus has an active students' society represented by the undergraduate Students' Society of McGill University (SSMU) and the Post-Graduate Students' Society of McGill University (PGSS). Due to the large postdoctoral student population, the PGSS also contains a semi-autonomous Association of Postdoctoral Fellows (APF). In addition, each faculty and department has its own student governing body, the largest faculty associations being the Arts Undergraduate Society (AUS) and the Science Undergraduate Society (SUS).[207][208] The oldest is the Medical Students Society, founded in 1859.[209]

SSMU supports more than 250 student-run membership clubs, which range from athletics, health and wellness, arts, and culture groups to professional development, charitable, volunteer, and political associations. It offers 17 student-run services, which provide services and resources to students regardless of membership, such as the Flat Bike Collective, Black Students' Network, McGill Students' Nightline, and Queer McGill (formerly Gay McGill),[210] which has supported queer students since 1972.[211][212] SSMU is also affiliated with 11 independent student groups, which operate on campus but are outside of the student society's governance structure. These independent groups include student media outlets, a legal clinic, AIESEC McGill, and the International Relations Students' Association of McGill (IRSAM),[213] which publishes the world's only all-inclusive international relations research journal, the McGill International Review,[214] and has consultative status with the UN Economic and Social Council and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.[215] IRSAM has hosted the McGill Model United Nations for University students since 1990 and the Secondary Schools United Nations Symposium since 1993.[216]

Many student clubs are centred around McGill's student union building, the University Centre. In 1992, students held a referendum calling for the University Centre to be renamed for actor and McGill alumnus William Shatner.[217] The university administration refused to accept the name and did not attend the opening because it traditionally names buildings in honour of deceased community members or major benefactors—Shatner is neither. Nevertheless, the University Centre has been informally referred to as the Shatner Building ever since.[218][219]

Student media

McGill has a number of student-run publications.The McGill Daily, first published in 1911, was previously published twice weekly,[220] but shifted to a once-a-week publication schedule in September 2013 due to tightened budgets.[221] The Délit français is the Daily's French-language counterpart. The combined circulation of both papers is over 28,000.[220] The McGill Tribune currently publishes once a week, circulating approximately 11,000 copies across campus. The Bull & Bear, operating under the Management Undergraduate Society, publishes 1,000 copies each month.[222] CKUT (90.3 FM) is the campus radio station. TVMcGill is the University TV station, broadcasting on closed-circuit television and over the internet.[223]

The McGill University Faculty of Law is home to three student-run academic journals, including the McGill Law Journal, founded in 1952.[224]

Greek life

The Greek system at McGill consists of several fraternities and sororities. Canada's only national fraternity, Phi Kappa Pi, was founded at McGill and the University of Toronto in 1913 and continues to be active. McGill was also chosen as the first University to expand to outside of the United States for several Greek letter organizations, for instance, with the Québec Alpha chapter of Phi Delta Theta in 1902.[225] The Greek letter organizations at McGill are governed by the Inter-Greek Letter Council, the school's second-largest student group.[226] Over 500 students or approximately 2 per cent of the student population are in sororities and fraternities at McGill, on a par with most Canadian schools but below the average for American universities.[227][228]

Athletics

McGill is represented in U Sports by the McGill Redbirds and Martlets with the Redbirds representing men's teams and the Martlets representing women's teams. McGill is currently home to 28 varsity teams. McGill is known for its strong baseball, hockey and lacrosse programs.[229][230] McGill's unique mascot, Marty the Martlet, was introduced during the 2005 Homecoming game.[231]

The downtown McGill campus sport and exercise facilities include: the McGill Sports Centre (which includes the Tomlinson Fieldhouse and the Windsor Varsity Clinic),[232] Molson Stadium, Memorial Pool, Tomlinson Hall, McConnell Arena, Forbes Field, many outdoor tennis courts and other extra-curricular arenas and faculties.[233]

The Macdonald Campus facilities include an arena, a gymnasium, a pool, tennis courts, fitness centres and hundreds of acres of green space for regular use.[234] The university's largest sporting venue, Molson Stadium, was constructed in 1914. Following an expansion project completed in 2010, it now seats just over 25,000,[235] and is the current home field of the Montreal Alouettes.[236]

Athletic history

In 1868, the first recorded game of rugby in North America occurred in Montreal, between British army officers and McGill students,[237][238] giving McGill the oldest University-affiliated rugby club in North America. Other McGill-originated sports evolved out of rugby rules: football, hockey, and basketball. The first game of North American football was played between McGill and Harvard on May 14, 1874,[239] leading to the spread of American football throughout the Ivy League.[240]

On March 3, 1875, the first organized indoor hockey game was played at Montreal's Victoria Skating Rink between two nine-player teams, including James Creighton and several McGill University students. The McGill University Hockey Club, the first organized hockey club, was founded in 1877[241] and played its first game on January 31, 1877.[242] Very soon thereafter, those McGill students wrote the first hockey rule book. A McGill team was one of four that competed in the Amateur Hockey Association of Canada, founded in 1886. AHAC teams competed for the first Stanley Cup in 1893; the AHAC became one of predecessor organizations of the National Hockey League.[243] McGill alumnus James Naismith invented basketball in early December 1891.[244]

There has been a McGill alumnus or alumna competing at every Olympic Games since 1908.[245][246][247] Swimmer George Hodgson won two gold medals at the 1912 Summer Olympics, ice hockey goaltender Kim St-Pierre won gold medals at the 2002 Winter Olympics and at the 2006 Winter Olympics. Other 2006 gold medalists are Jennifer Heil (women's freestyle mogul) and goaltender Charline Labonté (women's ice hockey).

A 2005 hazing scandal forced the cancellation of the final two games in the McGill Redmen football season.[248][249]

In 2006, McGill's Senate approved a proposed anti-hazing policy to define forbidden initiation practices.[250]

In 2018, after a slew of protests—both online and on-campus—an online vote revealed that 78.8 per cent of the McGill student population were in favour of changing the varsity teams' "Redmen" name, with 21 per cent against.[251] The university's nickname emerged in the 1920s. In the 1950s, both men's and women's teams came to be nicknamed the "Indians" and "Squaws", and some teams later adopted a logo of an indigenous man wearing a headdress in the 1980s and '90s. In December 2018, McGill University released a working group report that revealed deep divisions between students and alumni who defend the nearly century-old name and those who feel it is derogatory to indigenous students. In January 2019, it was announced that the principal Suzanne Fortier would decide whether or not to change the name by the end of the 2019 academic term.[252]

In 2019, an announcement confirmed that the Redmen name for its men's varsity sports teams had been dropped. No new name was planned; the groups would be known as the McGill teams. However, in 2020 McGill University revealed that the varsity men's sports teams would be known as the "Redbirds". The name carries historical links to several McGill sports clubs, teams, and events.[253] The former name would remain in the McGill Sports Hall of Fame and on items such as existing plaques, trophies and championship photos.[254]

Rivalries

McGill maintains an academic and athletic rivalry with Queen's University in Kingston, Ontario. Competition between rowing athletes at the two schools has inspired an annual boat race between the two universities in the spring of each year since 1997, inspired by the famous Oxford-Cambridge Boat Race.[255] The football rivalry, which started in 1884, ended after Canadian University athletic divisions were re-organized in 2000; the Ontario-Quebec Intercollegiate Football Conference was divided into Ontario University Athletics and Quebec Student Sports Federation.[256] The rivalry returned in 2002 when it transferred to the annual home-and-home hockey games between the two institutions. Queen's students refer to these matches as "Kill McGill" games, and usually show up in Montreal in atypically large numbers to cheer on the Queen's Golden Gaels hockey team.[257] In 2007, McGill students arrived in bus-loads to cheer on the McGill Redmen, occupying a third of Queen's Jock Harty Arena.[258]

The school also competes in the annual "Old Four (IV)" soccer tournament, with Queen's University, the University of Toronto and the University of Western Ontario.[259]

McGill and Harvard are also athletic rivals, as demonstrated by the biennial Harvard-McGill rugby games, alternately played in Montreal and Cambridge.[260]

-

The Queen's-McGill Challenge Blade

-

The Lorne Gales Trophy

Notable people

McGill alumni have played pivotal roles in the founding of several institutions of higher education. These include the first President of the University of British Columbia (UBC) Frank Wesbrook,[261] the former President of UBC and current President of the University of Michigan Santa J. Ono, the co-founder of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine William Osler,[262] and the first President of the University of Alberta Henry Marshall Tory.[263] More recent academic leaders include pro chancellor of Khaja Bandanawaz University Syed Muhammad Ali Al Hussaini, President of Princeton University Harold Tafler Shapiro,[264] President of Stanford University Marc Trevor Tessier-Lavigne,[265] and Vice-Chancellor of the University of Cambridge Stephen Toope.[266]

In the arts, McGill students include four Pulitzer Prize winners,[note 4] Templeton and Berggruen Prize winner Charles Taylor,[267] essayist and novelist John Ralston Saul, and Emmy Award-winning actor William Shatner.

In the sciences, McGill graduates and faculty have received a total of 12 Nobel Prizes in disciplines ranging from Physiology, Medicine, Economics, Chemistry and Physics. McGill has also produced five astronauts out of 14 total selected in the CSA's history.[268] Other prominent science alumni include the inventor of the artificial cell Thomas Chang,[269] inventor of the internet search engine Alan Emtage,[270] inventor of the explosives vapour detector (EVD-1) Lorne Elias,[271] and Turing Award winner Yoshua Bengio.[272]

In law and politics, McGill alumni include three Prime Ministers of Canada (John Abbott,[273] Wilfrid Laurier[274] and Justin Trudeau[275]), one Governor General of Canada (Julie Payette[276]). A number of foreign leaders have graduated from McGill including President of Costa Rica Daniel Oduber Quirós,[277] President of Latvia Vaira Vīķe-Freiberga,[278] Prime Minister of Egypt Ahmed Nazif.[279] John Peters Humphrey, law professor and director of the United Nations Division on Human Rights, wrote with Eleanor Roosevelt the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.[280]

In sport, McGill students and alumni include 121 Olympians who have won 35 Olympic medals.[21] Other notable sporting alumni include the inventor of basketball James Naismith,[281] influential baseball statistician Allan Roth,[282] the first medical doctor to win a Super Bowl Laurent Duvernay-Tardif,[283] and Triple Gold Club member Mike Babcock.[284]

- Notable McGill alumni include:

-

3rd prime minister of Canada Sir John Abbott (BCL, 1847).

-

7th prime minister of Canada Sir Wilfrid Laurier (BCL, 1864).

-

Inventor of the game of basketball James Naismith (BA, 1887).

-

First woman elected to the Quebec National Assembly Marie-Claire Kirkland (BA 1947, BCL 1950).

-

Co-inventor of the CCD and Nobel prize laureate in Physics Willard Boyle (BSc, 1947; MSc 1948; PhD 1950).

-

Emmy Award winner known for his portrayal of Captain Kirk in the Star Trek franchise William Shatner (BComm, 1952).

-

Balzan Prize winner, referred to as "the founder of neuropsychology" Brenda Milner (PhD, 1952)

-

Grammy Award winner and poet Leonard Cohen (BA, 1955).

-

6th President of Latvia Vaira Vīķe-Freiberga (PhD, 1965).

-

48th Prime Minister of Egypt Ahmed Nazif (PhD, 1983).

-

Former astronaut and 29th governor general of Canada Julie Payette (BEng, 1986).

-

Turing Award winner Yoshua Bengio (BEng, 1986; MSc, 1988; PhD, 1991).

-

The current and 23rd prime minister of Canada Justin Trudeau (BA, 1994).

-

Former international president of Médecins Sans Frontières Joanne Liu (MDCM, 1991; IMHL, 2014).

See also

- List of McGill University people

- McGill University School of Architecture

- Schulich School of Music

- Academic dress of McGill University

- Canadian government scientific research organizations

- Canadian industrial research and development organizations

- Canadian university scientific research organizations

- Cundill History Prize, awarded by McGill

- History Trek, developed by McGill researchers

- List of Canadian universities by endowment

- List of oldest universities in continuous operation

- Maude Abbott Medical Museum

- McGill University Non-Academic Certified Association

- McGill University School of Information Studies

- Montreal Laboratory (for nuclear research, World War II)

- Osler Library of the History of Medicine

- McGill University Department of Social Studies of Medicine

- U15 Group of Canadian Research Universities

- Montreal experiments

Notes

- ^ McGill alumni who have received Academy Awards include Torill Kove, Kate Biscoe, Richard King, Demetri Terzopoulos, Edward Saxon, Jake Eberts, John Weldon, Beverly Shaffer, and Burt Bacharach.

- ^ McGill alumni who have received Grammy Awards include George Massenburg, Estelí Gomez, Şerban Ghenea, Steven Epstein, Jennifer Gasoi, Brian Losch, Chilly Gonzales, Win Butler, Nick Squire, Leonard Cohen, Richard King, Régine Chassagne, and Burt Bacharach.

- ^ McGill alumni who have received Emmy Awards include Hume Cronyn, Eva Lipman, Mila Aung-Thwin, Alex Herschlag, David Bernad, Amy Schatz, Billy Wisse, Robby Hoffman, Kate Biscoe, Simcha Jacobovici, Jennifer Baichwal, Roberto Hernández, Blake Sifton, Kevin Mambo, and William Shatner.

- ^ a b These are Leon Edel (1963), Charles Krauthammer (1987), John F. Burns (1993, 1997[19]) and Matthew Rosenberg (2018).[20]

References

- ^ "Policy on use of the Wordmark and Insignia of McGill University" (PDF). McGill.ca. June 12, 2000. p. 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 16, 2021. Retrieved May 16, 2021.

- ^ a b c "The Gallery: 1821 Charter". McGill University Archives. May 17, 1940. Archived from the original on July 30, 2012. Retrieved June 4, 2012.

- ^ March 31, 2024 "Quarterly Reports | Office of Investments - McGill University". Archived from the original on September 18, 2024.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ "McGill University Budget 2021–2022" (PDF). McGill University. 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 5, 2022. Retrieved December 4, 2022.

- ^ "McGill University appoints H. Deep Saini as new Principal and Vice-Chancellor". November 14, 2022. Archived from the original on November 26, 2022. Retrieved November 27, 2022.

- ^ McGill Reporter Staff (December 12, 2023). "Leadership nomenclature change: Principal to President". McGill Reporter. Retrieved April 25, 2024.

- ^ "McGill FY 2022 Budget Book - Table 4: Staff Headcount, as of January 31 each year" (PDF). mcgill.ca. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 24, 2022. Retrieved May 30, 2022.

- ^ "McGill FY 2022 Budget Book - Table 4: Staff Headcount, as of January 31 each year" (PDF). mcgill.ca. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 24, 2022. Retrieved May 30, 2022.

- ^ a b c d "Enrolments Report". McGill University. 2022. Archived from the original on September 24, 2019. Retrieved April 2, 2022.

- ^ a b "Campus Planning". 2015. Archived from the original on November 6, 2018. Retrieved June 3, 2015.

- ^ Visual identity guide. McGill Visual Identity. (2021, September 23). Retrieved April 21, 2022, from https://mcgill.ca/visual-identity/visual-identity-guide#visualsystems Archived August 4, 2020, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c Frost, Stanley Brice. McGill University, Vol. I. For the Advancement of Learning, 1801–1895. McGill-Queen's University Press, 1980. ISBN 978-0-7735-0353-3

- ^ "Who was James McGill?". McGill. Retrieved April 11, 2024.

- ^ "Association of American Universities". Aau.edu. Archived from the original on January 14, 2013. Retrieved November 5, 2012.

- ^ a b "McGill newsroom". Archived from the original on May 11, 2016. Retrieved May 12, 2016.

- ^ a b "Enrolment Reports". McGill University. Archived from the original on September 23, 2017. Retrieved April 26, 2010.

- ^ "McGill University: Tuition and Profile". www.macleans.ca. Archived from the original on October 19, 2020. Retrieved October 18, 2020.

- ^ McDevitt, Neale (December 19, 2023). "Keeping her eye on the Rhodes". McGill Reporter. Archived from the original on January 24, 2024. Retrieved April 5, 2024.

- ^ "The 1997 Pulitzer Prize Winners". Pulitzer.org. October 4, 1944. Archived from the original on January 8, 2010. Retrieved February 20, 2011.

- ^ "National Reporting". Pulitzer.org. April 16, 2018. Archived from the original on April 26, 2017. Retrieved May 23, 2018.

- ^ a b "10 Things: McGill in the Olympics". The McGill Tribune. April 5, 2016. Archived from the original on August 3, 2020. Retrieved March 11, 2020.

- ^ "An Act for the Establishment of Free Schools and the Advancement of Learning in this Province" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on April 20, 2016. Retrieved April 6, 2016.

- ^ "Education". McGill University Archives. Archived from the original on February 25, 2021. Retrieved June 4, 2012.

- ^ Guide to the Archives, vol. 2 Archived February 25, 2021, at the Wayback Machine at archives.mcgill.ca, accessed 28 December 2017

- ^ James Collins Miller, National Government and Education in Federated Democracies, Dominion of Canada (1940), p. 44

- ^ "James McGill – Quebec History". Faculty.marianopolis.edu. Archived from the original on February 24, 2021. Retrieved June 4, 2012.

- ^ Everett-Green, Robert (May 12, 2018). "200 Years a Slave: The Dark History of Captivity in Canada". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on June 15, 2019. Retrieved September 25, 2019.

- ^ "Who was James McGill?". About McGill. Retrieved May 1, 2024.

- ^ Millman, Thomas R. "Mountain, Jacob". Archived from the original on March 13, 2016. Retrieved June 8, 2008.

- ^ "History". McGill University General Information. March 8, 2007. Archived from the original on September 4, 2017. Retrieved September 4, 2017.

- ^ "The Gallery: James McGill's Will". McGill University Archives. 2003. Archived from the original on June 30, 2017. Retrieved May 2, 2008.

- ^ a b "Colleges A–M". Kipnotes.com. 2001. Archived from the original on February 24, 2012. Retrieved June 8, 2008.

- ^ "Foundation History". McGill University. Archived from the original on September 4, 2017. Retrieved June 4, 2012.

- ^ "Principal George Jehoshaphat Mountain, 1824-1835". McGill University Archives. 2003. Archived from the original on January 27, 2020. Retrieved July 18, 2020.

- ^ Crawford, DS. Montreal, medicine and William Leslie Logie: McGill's first graduate and Canada's first medical graduate. 175th. anniversary. Osler Library Newsletter # 109, 2008 [1] Archived November 13, 2018, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Department History". McGill University Health Centre, Montreal. August 13, 2005. Archived from the original on January 13, 2009. Retrieved January 13, 2009.

- ^ Marco Polo. "Architectural Education". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on July 21, 2019. Retrieved August 18, 2019.

- ^ "McGill University Faculty of Medicine: History". Archived from the original on July 23, 2011. Retrieved July 23, 2011.

- ^ "Spier, William". Dictionaryofarchitectsincanada.org. Archived from the original on October 21, 2014. Retrieved June 4, 2012.

- ^ "Alexander Francis Dunlop". Dictionaryofarchitectsincanada.org. Archived from the original on June 1, 2020. Retrieved June 4, 2012.

- ^ "Biographic Dictionary of Architects in Canada 1800–1950 Andrew Taylor (Architect)". Dictionaryofarchitectsincanada.org. Archived from the original on April 25, 2012. Retrieved June 4, 2012.

- ^ "Jean Julien Perrault (architect)". Dictionaryofarchitectsincanada.org. Archived from the original on March 3, 2012. Retrieved June 4, 2012.

- ^ Michael Clarke. "William Dawson". Ccheritage.ca. Archived from the original on May 17, 2008. Retrieved June 4, 2012.

- ^ "Royal Victoria College". McGill University Archives. March 24, 2004. Archived from the original on February 24, 2021. Retrieved June 4, 2012.

- ^ a b "Royal Victoria College". McGill Student Housing. April 1, 2022. Archived from the original on April 1, 2022. Retrieved April 1, 2022.

- ^ "Our History: George S. Currie and George C. McDonald". PricewaterhouseCoopers Canada. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved September 20, 2014.

- ^ "The Stained Glass War Memorials of Charles William Kelsey" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on February 25, 2021. Retrieved June 4, 2012.

- ^ "McGill Chapter of Delta Upsilon Great War Memorial Window". Chief Military Personnel. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved September 20, 2014.

- ^ "McGill University remembers the Second World War". McGill University. 2013. Archived from the original on February 24, 2021. Retrieved September 20, 2014.

- ^ "Higher Education in British Columbia Before the Establishment of UBC – UBC Archives". Library.ubc.ca. Archived from the original on May 23, 2012. Retrieved June 4, 2012.

- ^ Edwards, Reginald. "Historical Background of the English-Language CEGEPs of Quebec". mje.mcgill.ca. Archived from the original on June 28, 2019. Retrieved April 22, 2019.

- ^ "The Four Founding Physicians". Johns Hopkins Medicine. Archived from the original on March 10, 2015. Retrieved August 27, 2014.

- ^ "The William Osler Papers: "Father of Modern Medicine": The Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, 1889-1905". profiles.nlm.nih.gov. March 13, 2019. Archived from the original on September 24, 2019. Retrieved April 22, 2019.

- ^ "Our History - Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry - Western University". www.schulich.uwo.ca. Archived from the original on September 10, 2019. Retrieved April 22, 2019.

- ^ B. Macdonald, John (1962). "Higher education in British Columbia and a plan for the future" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on February 16, 2023. Retrieved February 16, 2023.

- ^ Fried, Jonah. "Making sense of McGill's underfunding crisis". The McGill Tribune. Archived from the original on February 16, 2023. Retrieved February 16, 2023.

- ^ Agarwal, Astha. "McGill faces $1.3 billion in deferred maintenance costs". The McGill Tribune. Archived from the original on February 16, 2023. Retrieved February 16, 2023.

- ^ "40% of Quebec university buildings in poor condition, government report says". CBC News. Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on February 16, 2023. Retrieved February 16, 2023.

- ^ Gerald Tulchinsky, Canada's Jews: A People's Journey, (Toronto: University of Toronto Press), 2008, p. 132-133, 319-321.

- ^ Tulchinsky, Canada's Jews, p. 133.

- ^ Tulchinsky, Canada's Jews, p. 410.

- ^ "Museum of Jewish Montreal". imjm.ca. Archived from the original on August 31, 2021. Retrieved July 24, 2021.

- ^ "Brief History of Antisemitism in Canada" (PDF). Holocaust Museum of Montreal.

- ^ Bélanger, Claude. "Quebec History". faculty.marianopolis.edu. Retrieved January 3, 2025.

- ^ Fineberg, Sheri (2009). "Jewish Students in Canadian Universities: The Rise and Fall of a Quota System". Canadian Content: The McGill Undergraduate Journal of Canadian Studies. 1: 147–171.

- ^ ""CBC News, Erika Morris, CBC News journalist, 9th January, 2023"". Archived from the original on May 15, 2023. Retrieved May 14, 2023.

- ^ "Campus Maps". Mcgill.ca. Archived from the original on August 27, 2016. Retrieved June 4, 2012.

- ^ "Study Places – McGill University". Educomp. 2008. Archived from the original on May 27, 2010. Retrieved October 5, 2014.

- ^ Keller, Lucy (November 20, 2018). "Student Life - Winter prep 101". The McGill Tribune. Archived from the original on February 18, 2022. Retrieved February 17, 2022.

many McGill buildings are connected so that students can stay inside in between classes and avoid low temperatures during the school day.

- ^ "'Brief history of Physics at McGill' – 'McGill Physics', 2008". Physics.mcgill.ca. December 17, 2010. Archived from the original on September 6, 2012. Retrieved June 4, 2012.

- ^ David Johnson. "The Early Campus – Virtual McGill". Cac.mcgill.ca. Archived from the original on July 7, 2012. Retrieved June 4, 2012.

- ^ David Johnson. "'Canadian Architecture Collection' – 'Virtual McGill', 2001". Cac.mcgill.ca. Archived from the original on July 7, 2012. Retrieved June 4, 2012.

- ^ "Macdonald Park, Molson [Percival] Stadium, Currie [Sir Arthur] Memorial Gymnasium, and McConnell Winter Stadium". Virtual McGill. McGill University. Archived from the original on July 3, 2023. Retrieved July 3, 2023.

- ^ "McGill Residences". Mcgill.ca. July 28, 2010. Archived from the original on March 8, 2011. Retrieved September 29, 2011.

- ^ "Student Housing". McGill University. March 31, 2022. Archived from the original on March 31, 2022. Retrieved March 31, 2022.

- ^ "The ghetto that isn't | The McGill Daily". February 10, 2014. Archived from the original on August 3, 2020. Retrieved May 7, 2020.

- ^ "'In the Ghetto', September 9, 1999". McGill Reporter. Archived from the original on February 28, 2021. Retrieved June 4, 2012.

- ^ "Upper Rez: Douglas, McConnell, Molson and Gardner Halls". "Moving into Residences" Archived 2008-04-16 at the Wayback Machine, "McGill University", 2008. Retrieved June 5, 2008.

- ^ "Upper Residence: McConnell Hall, Gardner Hall, Molson Hall". McGill Student Housing. March 31, 2022. Archived from the original on March 31, 2022. Retrieved March 31, 2022.

- ^ "Percy Erskine Nobbs Biography". McGill John Bland Canadian Architecture Collection – The Architecture of Percy Erskine Nobbs. Archived from the original on November 9, 2013. Retrieved February 26, 2014.

- ^ Morgan, Henry James, ed. (1903). Types of Canadian Women and of Women who are or have been Connected with Canada. Toronto: Williams Briggs. p. 1.

- ^ "An Introduction to the Arboretum". Archived from the original on September 23, 2007.

- ^ a b c "McGill opens satellite medical faculty in the Outaouais". CBC News. Archived from the original on March 29, 2022. Retrieved February 11, 2019.

- ^ "L'UQO déçue de ne pas accueillir la future faculté de médecine". Société Radio-Canada. Radio-Canada. September 7, 2016. Archived from the original on September 20, 2020. Retrieved April 27, 2020.

- ^ "McGill est l'UQO vont offrir l'année préparatoire en médecine à Gatineau". Université du Québec. Université du Québec en Outaouais. February 13, 2020. Archived from the original on September 27, 2023. Retrieved April 27, 2020.

- ^ "'The MUHC Redevelopment Project', 2008". McGill University Health Centre. Archived from the original on August 19, 2007. Retrieved June 4, 2012.

- ^ "This Land Was Made for You and Me... McGill University Health Centre Journal, July/August 2001". Archived from the original on August 29, 2005.

- ^ McCabe, Daniel. MUHC site chosen Archived August 25, 2006, at the Wayback Machine, McGill Reporter, November 5, 1998.

- ^ a b "Sustainability". McGill University. Archived from the original on July 7, 2009. Retrieved June 5, 2009.

- ^ "Office of Sustainability: Campus Committees and GroupsSustainability". McGill University. Archived from the original on March 30, 2009. Retrieved June 5, 2009.

- ^ "MCLL celebrates its 30th anniversary". McGill Reporter. November 5, 2019. Archived from the original on January 22, 2021. Retrieved February 24, 2021.

- ^ Frisby, Sandra; Huff, Christie; Megelas, Alex; Thorvik, Astri. "Expanding the Concept of Lifelong Learning Beyond the Campus: The Experience of the McGill Community for Lifelong Learning within the Wider Quebec Community" (PDF). McGill University. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 28, 2022. Retrieved December 29, 2021.

- ^ "Bloomsday: how fans around the world will be celebrating James Joyce's Ulysses". The Guardian. June 15, 2015. Archived from the original on June 28, 2021. Retrieved May 16, 2021.

- ^ "Bellairs Research Institute, McGill University". Mcgill.ca. April 11, 2011. Archived from the original on June 11, 2002. Retrieved June 4, 2012.

- ^ "THE GAULT NATURE RESERVE, McGill University. Accessed May 3, 2008". Biology.mcgill.ca. Archived from the original on October 1, 2011. Retrieved June 4, 2012.

- ^ Research and education Archived 2017-09-07 at the Wayback Machine, McGill University. Accessed May 3, 2008.

- ^ "Mcgill University" Archived 2010-01-23 at the Wayback Machine, "Learnist.org Study Abroad", 2008. Accessed May 16, 2008.

- ^ ""McGill University Teaching Hospital Network" – "McGill University Faculty of Medicine"". Archived from the original on May 6, 2008.

- ^ a b "Faculties and Schools – McGill University". McGill University. Archived from the original on May 13, 2020. Retrieved October 5, 2021.

- ^ "Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies". McGill University. Archived from the original on September 6, 2017. Retrieved March 16, 2008.

- ^ "1900-1950 - McGill Faculty of Engineering History". McGill University. Archived from the original on April 12, 2020. Retrieved April 5, 2020.

- ^ "Policy on use of the Wordmark and Insignia of McGill University" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on February 26, 2015. Retrieved August 26, 2015.

- ^ "McGill Songs > McGill Facts and Institutional History > McGill History > Outreach". Archives.mcgill.ca. March 24, 2004. Archived from the original on April 4, 2007. Retrieved February 20, 2011.

- ^ "McGill students going abroad". McGill Abroad, McGill University. Archived from the original on March 27, 2020. Retrieved March 27, 2020.

- ^ "About International Student Services (ISS)". McGill University. Archived from the original on March 17, 2019. Retrieved March 14, 2019.

- ^ Munroe-Blum, Heather (February 9, 2009). "Economic Statement, Feb. 9, 2009". Archived from the original on April 9, 2009. Retrieved May 16, 2021.

- ^ Tibbets, Janice. "U of T, UBC join billion-dollar club" Archived 2011-05-11 at the Wayback Machine, "Canwest News Service", February 3, 2008. Accessed May 4, 2008.

- ^ "McGill Endowment Quarterly Report Dec 2020" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on April 24, 2021. Retrieved March 24, 2021.

- ^ "McGill University | Canada". www.easyuni.com. Archived from the original on May 16, 2021. Retrieved May 15, 2021.

- ^ "McGill launches $750-million fundraiser" Archived 2011-05-11 at the Wayback Machine, "The Montreal Gazette" October 18, 2007. Accessed May 4, 2008.

- ^ a b "History in the Making" Archived July 7, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, "McGill Public and Media Newsroom", October 18, 2007. Accessed May 4, 2008.

- ^ "McGill launches largest Canadian university fundraising campaign" Archived 2010-12-05 at the Wayback Machine, "Academia Group Back Issues Database" October 19, 2007. Accessed May 4, 2008.

- ^ "McGill University joins $1-billion fundraising club". Archived from the original on June 20, 2013. Retrieved June 19, 2013.

- ^ "McGill University's fundraising tops $1 billion". Archived from the original on June 21, 2013. Retrieved June 19, 2013.

- ^ "About Defy Gravity: The Campaign for the University of Toronto". Defy Gravity. University of Toronto. Retrieved November 5, 2023.

- ^ "FORWARD, the campaign for UBC". University of British Columbia. Retrieved November 5, 2023.

- ^ "Introducing "Made by McGill"". McGill University. September 26, 2019. Retrieved November 5, 2023.

- ^ "University of Toronto receives single largest gift in Canadian history". Archived from the original on September 29, 2020. Retrieved June 30, 2021.

- ^ "McCall MacBain Foundation makes a single-largest gift in Canadian history to create a flagship graduate scholarship program at McGill University". Newsroom. Archived from the original on February 14, 2019. Retrieved February 13, 2019.

- ^ "Admissions Profile". Enrolment Services. Archived from the original on October 15, 2015. Retrieved May 21, 2023.

- ^ "McGill University 2020-2021 Admissions: Entry Requirements, Deadlines, Application Process". Collegedunia. April 9, 2020. Archived from the original on August 3, 2020. Retrieved April 27, 2020.

- ^ "McGill University 2022-2023 Admissions: Entry Requirements, Deadlines, Application Process". LeapScholar. November 25, 2022. Archived from the original on November 25, 2022. Retrieved November 25, 2022.

- ^ Gazette, The (May 15, 2008). "McGill buys Anglican Diocesan Theological College". Canada.com. Archived from the original on August 22, 2012. Retrieved June 4, 2012.