Archie Roach

Archie Roach | |

|---|---|

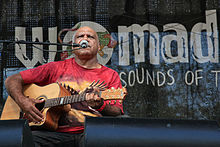

Roach in 2016 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Archibald William Roach |

| Born | 8 January 1956 Mooroopna, Victoria, Australia |

| Died | 30 July 2022 (aged 66) Warrnambool, Victoria, Australia |

| Genres | Folk, ballads, Aboriginal rock |

| Occupation(s) | Musician, songwriter, storyteller |

| Instrument(s) | Vocals, six-string guitar |

| Years active | 1980s–2022 |

| Labels | Mushroom, Liberation Music, ABC Music |

| Website | archieroach.com |

Archibald William Roach AC (8 January 1956 – 30 July 2022) was an Australian singer-songwriter and Aboriginal activist. Often referred to as "Uncle Archie", Roach was a Gunditjmara (Kirrae Whurrong/Djab Wurrung[1]) and Bundjalung elder who campaigned for the rights of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. His wife and musical partner was the singer Ruby Hunter (1955–2010).

Roach first became known for the song "Took the Children Away", which featured on his debut solo album, Charcoal Lane, in 1990. He toured around the globe, headlining and opening shows for Joan Armatrading, Bob Dylan, Billy Bragg, Tracy Chapman, Suzanne Vega and Patti Smith. His work has been recognised by numerous nominations and awards, including a Deadly Award for a "Lifetime Contribution to Healing the Stolen Generations" in 2013. At the 2020 ARIA Music Awards on 25 November 2020, Roach was inducted into their hall of fame. His 2019 memoir and accompanying album were called Tell Me Why.

Early life

[edit]Archibald William Roach was born on 8 January 1956 in Mooroopna, Victoria.[2] Roach was of Gunditjmara (Kirrae Whurrong / Djab Wurrung)[3] and Bundjalung heritage.[4]

In 1956, Roach's family,[5] along with the remaining Aboriginal population at Cummeragunja,[6][7] were rehoused at Rumbalara. The family subsequently moved to Framlingham, where his mother had been born.[5][8][9]

At the age of two or three, Roach and his sisters and brothers, along with the other Indigenous Australian children of the Stolen Generations, were forcibly removed from their family by government agencies and placed in an orphanage.[10][11][4] After two unpleasant placements in foster care, Roach was eventually fostered by Alex and Dulcie Cox, a family of Scottish immigrants in Melbourne.[12] Their eldest daughter Mary Cox would sing church hymns and taught Roach the basics of guitar and keyboards.[13] Roach's love of music was further fuelled by Alex's collection of Scottish music. "He was a big influence on me — a good influence. I'll love him to the day I die."[12]

At fifteen, Roach was contacted by his natural sister Myrtle, who told him their mother had just died. He spent the next fourteen years on the streets, battling alcoholism. Roach met his future wife, Ruby Hunter,[11] at a Salvation Army drop-in centre known as the People's Palace in Adelaide[14] when she was sixteen.[11]

Career

[edit]Roach's career spanned three decades, during which he toured extensively, headlining and opening shows for singers such as Joan Armatrading, Bob Dylan, Billy Bragg, Tracy Chapman, Suzanne Vega and Patti Smith.[15]

1989–2000: Charcoal Lane, Jamu Dreaming and Looking for Butter Boy

[edit]In the late 1980s, Roach and Hunter formed a band, the Altogethers, with several other Indigenous Australians and moved to Melbourne. At the urging of Henry "Uncle Banjo" Clark,[16] Roach wrote his first song, "Took the Children Away", which he performed on a community radio station in Melbourne and on an Indigenous current affairs program in 1988. Australian musician Paul Kelly invited Roach to open his concert early in 1989, where he performed "Took the Children Away", a song telling the story of the Stolen Generations and his own experience of being forcibly removed from his family.[17] His performance was met with stunned silence, followed by shattering applause.[11]

In 1990, with the encouragement of Kelly, Roach recorded his debut solo album, Charcoal Lane, which was released in May 1990. The album was certified gold and awarded two ARIA Awards at the 1991 ceremony. The album included "Took the Children Away" which became one of the most important songs in Australia's contemporary history.[18] In 1990, Australia's Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission's awarded the song its first Human Rights Award for songwriting.[19] Charcoal Lane featured in the top 50 albums for 1992 by Rolling Stone magazine.[11]

In May 1993, Roach released his second studio album, Jamu Dreaming. The album was recorded with musical assistance from David Bridie, Tiddas, Paul Kelly, Vika and Linda Bull, Ruby Hunter, Dave Arden and Joe Geia.[20] The album peaked at number 55 on the ARIA Charts.[21]

In 1995, Roach toured extensively throughout the US, Canada, the UK and Europe. He returned to Australia to record the title track for ATSIC's Native Title CD, Our Home, Our Land, with Tiddas, Kev Carmody, Bart Willoughby, Shane Howard and Bunna Laurie. In 1996, Roach performed as part of a presentation to the Human Rights Commission's Inquiry into the Stolen Generations, before embarking on a national tour as a guest of Tracy Chapman.[22]

In October 1997, Roach released his third studio album, Looking for Butter Boy, which was recorded on his traditional land at Port Fairy in south-western Victoria.[20] The album's lead single, "Hold On Tight", won the ARIA Award for Best Indigenous Release in 1997[23] and the album won the same award and the Best Adult Contemporary Album at the 1998 award ceremony.[24]

2001–2009: Sensual Being and Journey

[edit]In July 2002, Roach released his fourth studio album, Sensual Being, which peaked at number 59 on the ARIA charts. In 2002, he worked on the Rolf de Heer film The Tracker.[25]

In 2004, Roach and Hunter collaborated with the Australian Art Orchestra (AAO) and Paul Grabowsky to create a concert titled Ruby's Story. Ruby tells the story of Ruby Hunter through music and the spoken word, from her birth near a billabong on the banks of the Murray River, through the Stolen Generations, search for identity and the discovery of hope through love.[26] The production debuted at the Message Sticks Festival at the Sydney Opera House in June 2004,[27] to good reviews.[26] In 2004, the soundtrack, Ruby, won the Deadly Award for Excellence in Film & Theatrical Score, and the show went on to tour nationally and internationally until 2009.[28] The soundtrack was released as an album on CD and as a digital download in 2005.[29]

In October 2004 a new concert, once again a collaboration with Hunter, Grabowsky and the AAO, entitled Kura Tungar – Songs from the River, premiered at the Melbourne International Arts Festival,[30] which was directed by Robyn Archer that year.[31] The concert, which was directed by Patrick Nolan, told stories from the two performers' lives, and featured songs about the Murray River and Ngarrindjeri Country, Ruby's home. The music used Roach and Hunter's lyrics and chords combined with Grabowsky and the AAO's contemporary jazz orchestration. It played to full houses which gave standing ovations and was later performed at the Sydney Opera House and Adelaide Festival Centre. In 2005 Kura Tungar won the Helpmann Award for the Best Contemporary Australian Concert at the 5th Helpmann Awards.[30] A documentary film of the preparation for the performance, including interviews and parts of the performance, directed by Philippa Bateman and called Wash My Soul in the Rivers Flow, was released in 2021.[32]

In October 2007, Roach released Journey, an album of songs as a companion piece to a documentary film called Liyarn Ngarn, made with Roach, Patrick Dodson and Pete Postlethwaite.[33]

In October 2009 at the Melbourne International Arts Festival, Roach performed in the world premiere of the musical theatre production of Dirtsong, created by Black Arm Band theatre company. The songs were written by Alexis Wright, with some sung in Indigenous languages. The show was reprised as the closing show at the 2014 Adelaide Festival. Other performers included Trevor Jamieson (2014 only), Lou Bennett, Emma Donovan, and Paul Dempsey.[34][35][36][37]

In November 2009, ABC Music released previously unreleased Roach recordings from 1988 under the album title 1988.[38]

2010–2016: Into the Bloodstream and Let Love Rule

[edit]

In October 2012, Roach released Into the Bloodstream, an album he described as being built on pain following the death of his wife in February 2010.[39] In 2013 he won a Deadly Award for Album of the Year for this album, as well as a "Lifetime Contribution to Healing the Stolen Generations".[40]

In October 2013, Roach released Creation, a 4-CD box set of his first four studio albums. The album was released to coincide with the premiere of Roach's new live show, also entitled Creation, which debuted at the inaugural Boomerang Festival in Byron Bay from 4 to 6 October 2013.[41]

At the APRA Music Awards of 2015 2015, Roach (and Shane Howard) won Best Original Song Composed for the Screen "The Secret River" from The Secret River.[42]

In November 2015, Roach celebrated the 25th anniversary of Charcoal Lane with a deluxe remastered edition. The new edition included a second disc featuring previously unreleased Triple J – Live At The Wireless recordings and new interpretations of classic Charcoal Lane material by various artists. In November and December 2015, Roach undertook a national tour to celebrate the album's 25th anniversary.[43]

In November 2016, Roach released his seventh studio album, Let Love Rule, which peaked at number 24 on the ARIA Charts, becoming his highest charting album to date.[44]

2017–2022: The Concert Collection 2012–2018 and Tell Me Why

[edit]At the APRA Music Awards of 2017 in March 2017, Roach won the Ted Albert Award for Outstanding Services to Australian Music.[17]

In April 2018, Roach performed at the Commonwealth Games closing ceremony on the Gold Coast with Amy Shark.[45]

In May 2019, Roach released The Concert Collection 2012–2018 and in July 2019, was nominated for two awards at the 2019 National Indigenous Music Awards.[46]

On 1 November 2019, Roach published a memoir entitled Tell Me Why: The Story of My Life and My Music,[47] and released a companion album, Tell Me Why, on the same day.[48] His book was shortlisted for the 2020 Victorian Premier's Prize for Nonfiction[49] and won the 2020 Indie Book Non-Fiction Award.[50] It also won the Audiobook of the Year at the 2021 Australian Book Industry Awards.[51] The album's lead single "Open Up Your Eyes" is the first song Roach ever wrote, dating back to the late 1970s, but had not before been recorded.[48] Tell Me Why became Roach's first top-ten album on the ARIA Charts.[49]

Wash My Soul in the River's Flow (2021), written and directed by Philippa Bateman and produced by Bateman, Kate Hodges and Roach, is a feature-length documentary film based on the 2004 concert Kura Tungar-Songs from the River, featuring Roach, Hunter, Paul Grabowsky and the Australian Art Orchestra,[30] in which Hunter and Roach sing about the Murray River and Ngarrindjeri lands.[52][53] The film also tells of the love story between Hunter and Roach, and is interspersed with vision of The Coorong.[54] The film had its world premiere at the Brisbane International Film Festival in October 2021[55] and was an official selection for the Sydney Film Festival and the Melbourne International Film Festival in December 2021.[56][57]

In March 2022, Roach released his career-spanning anthology, titled My Songs: 1989–2021,[58][59] which was subsequently nominated as the Album of the Year for the 2022 National Indigenous Music Awards two weeks before his death.[60] At the 2022 ARIA Music Awards a special tribute in his honour will have Budjerah, Jessica Mauboy and Thelma Plum performing "One Song" from that album.[61]

In 2023, the Roach and Hunter authored book Songs from the Kitchen Table was released, including lyrics, stories, photographs.[62]

Activism

[edit]In 2013, shortly after receiving his Lifetime Deadly Award, Roach called on the recently elected prime minister, Tony Abbott, for an end to the Northern Territory Intervention.[40]

Discography

[edit]- Charcoal Lane (1990)

- Jamu Dreaming (1993)

- Looking for Butter Boy (1997)

- Sensual Being (2002)

- Journey (2007)

- Into the Bloodstream (2012)

- Let Love Rule (2016)

- Dancing with My Spirit (2018)

- Tell Me Why (2019)

- The Songs of Charcoal Lane (2020)

Personal life

[edit]

Roach was married to the singer Ruby Hunter (died 2010) who was also his musical partner. They had two sons, Amos and Eban. They also had three foster children, Kriss, Terrence and Arthur.[63]

On 14 October 2010, Roach suffered a stroke while working in the Kimberley region.[64][65] After recuperating, he returned to live performance in April 2011. He also survived lung cancer, due to early diagnosis in 2011 and major surgery.[66]

Death and legacy

[edit]Roach died on 30 July 2022 at Warrnambool Base Hospital. His sons, Amos and Eban, have given permission for his name and image to be posthumously used freely "so that his legacy will continue to inspire". This permission is limited to news.[67][3] Tributes were paid to his memory by prominent names in arts, politics and sport including Australian prime minister Anthony Albanese, Victorian premier Daniel Andrews and musicians including Emma Donovan, Briggs, John Schumann, Alice Skye, Emily Wurramara, Paul Kelly, Billy Bragg, Mark Seymour, Midnight Oil and Shane Howard.[68]

In 2022, two side-by-side pillar-shaped monuments were erected on the shores of Lake Bonney at Barmera, in homage to Roach and Hunter. A glass mosaic artwork on the front side of each monument depict Roach's totem, the eagle, and Hunter's Ngarrindjeri totem, the pelican (nori).[69] In 2024, a statue of Roach and Hunter was erected at Atherton Gardens in Fitzroy.[70]

Roach was regarded as giving a voice to the stories of many Aboriginal people and offering comfort and healing in his words and music.[63] Euahlayi scholar Bhiamie Williamson, who wrote his PhD thesis on "Indigenous Men and Masculinities",[71] describes the concept of the "Emu Man", based on the male emu, which is devoted to his family and chicks and sits on the eggs. Roach was considered a role model who represented an image shown too rarely in public discourse. Williamson writes:[63]

He gave us – and all of Australia – an image of an Aboriginal man, tender and humble. An image long denied us ... Through his life, his dedication to Aunty Ruby, his devotion to his sons, his work with disengaged youth and his profound love for his people, Uncle Archie gave the nation an image of an Aboriginal man seldom found in the national psyche ...

Archie Roach Foundation

[edit]The Archie Roach Foundation was established in 2014 to nurture talent in young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and to offer them opportunities in the arts, to provide connection to culture and healing.[72] As of 2022[update], the board of directors included Roach, Uncle Jack Charles and four other people, with Charles and Rhoda Roberts as ambassadors of the foundation.[73] The foundation has supported hundreds and inspired thousands more young people. His work in youth detention centres continues to affect those who listened to him.[63]

Honours

[edit]- In 2011, Roach was one of the first people inducted to the Victorian Aboriginal Honour Roll.[74]

- In 2015, Roach was honoured in the Queen's Birthday Honours list as a Member of the Order of Australia (AM) for services to music as a singer-songwriter, guitarist and a prominent supporter of social justice.[75]

- In 2020, Roach was named the 2020 Victoria Australian of the Year.[76]

- In 2023, Roach was posthumously promoted to Companion of the Order of Australia (AC) for "eminent service to the performing arts as a songwriter and musician, to Indigenous rights and reconciliation, and through support for emerging First Nations artists".[77]

Recognition and awards

[edit]"Took the Children Away" was added to the National Film and Sound Archive's Sounds of Australia registry in 2013.[78]

AIR Awards

[edit]The Australian Independent Record Awards (commonly known informally as AIR Awards) is an annual awards night to recognise, promote and celebrate the success of Australia's Independent Music sector.

| Year | Nominee / work | Award | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2017[79][80] | Let Love Rule | Best Independent Blues and Roots Album | Nominated |

APRA Awards

[edit]The APRA Awards are held in Australia and New Zealand by the Australasian Performing Right Association to recognise songwriting skills, sales and airplay performance by its members annually. They commenced in 1982.[81]

| Year | Nominee / work | Award | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | Archie Roach | Ted Albert Award for Outstanding Services to Australian Music | awarded | [82][83] |

| "It's Not Too late" | Song of the Year | Shortlisted | [84] | |

| 2020 | "Open Up Your Eyes" | Song of the Year | Shortlisted | [85] |

| 2021 | "Tell Me Why" (with Sally Dastey) | Song of the Year | Shortlisted | [86] |

| 2023 | "One Song" | Song of the Year | Nominated | [87] |

ARIA Awards

[edit]Roach has received ten ARIA Music Awards from twenty-three nominations.[88]

| Year | Nominee / work | Award | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1991 | Charcoal Lane | Best New Talent | Won |

| Best Indigenous Release | Won | ||

| Breakthrough Artist – Album | Nominated | ||

| "Took the Children Away" | Breakthrough Artist – Single | Nominated | |

| 1992 | "Down City Streets" | Best Indigenous Release | Nominated |

| 1994 | Jamu Dreaming | Best Indigenous Release | Nominated |

| 1997 | "Hold On Tight" | Best Indigenous Release | Won |

| 1998 | Looking for Butter Boy | Best Indigenous Release | Won |

| Best Adult Contemporary Album | Won | ||

| 2002 | Sensual Being | Best Adult Contemporary Album | Nominated |

| Richard Pleasance & Paul Kelly for Sensual Being | Producer of the Year | Nominated | |

| The Tracker | Best Original Soundtrack Album | Nominated | |

| 2008 | Journey | Best World Music Album | Nominated |

| 2010 | 1988 | Best World Music Album | Nominated |

| 2013 | Into the Bloodstream | Best Blues & Roots Album | Nominated |

| 2017 | Let Love Rule | Best Blues & Roots Album | Nominated |

| 2020 | Tell Me Why | Best Male Artist | Won |

| Best Adult Contemporary Album | Won | ||

| Best Independent Release | Nominated | ||

| Archie Roach | Hall of Fame | Inductee[15] | |

| 2021[89] | The Songs of Charcoal Lane | Best Blues & Roots Album | Won |

| Best Independent Release | Nominated | ||

| 2022[90][91] | "One Song" | Best Independent Release | Won |

Australia Council for the Arts

[edit]The Australia Council for the Arts is an arts funding and advisory body for the Government of Australia. Since 1993 it has awarded a Red Ochre Award. It is presented to an outstanding Indigenous Australian (Aboriginal Australian or Torres Strait Islander) artist for lifetime achievement.

| Year | Nominee / work | Award | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | himself | Red Ochre Award | Awarded[92] |

Deadly Awards

[edit]The Deadly Awards (commonly known simply as The Deadlys) was an annual celebration of Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander achievement in music, sport, entertainment and community. They ran from 1996 to 2013.

| Year | Nominee / work | Award | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1997[93] | "himself" | Male Artist of the Year | Won |

| 1998[94] | "himself" | Male Artist of the Year | Won |

| 2002[95] | "himself" | Male Artist of the Year | Won |

| Sensual Being | Album of the Year | Won | |

| 2003[96] | "himself" | Outstanding Contribution to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Music | Won |

| 2004[97] | Ruby (with Ruby Hunter and Paul Grabowsky) | Excellence in Film & Theatrical Score | Won |

| 2010[98] | 1988 | Album of the Year | Won |

| 2013[40] | Into the Bloodstream | Album of the Year | Won |

| "himself" | The Lifetime Contribution Award For Healing The Stolen Generations | inductee |

Don Banks Music Award

[edit]The Don Banks Music Award was established in 1984 to publicly honour a senior artist of high distinction who has made an outstanding and sustained contribution to music in Australia.[99] It was founded by the Australia Council in honour of Don Banks, Australian composer, performer and the first chair of its music board.

| Year | Nominee / work | Award | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | Archie Roach | Don Banks Music Award | awarded[100] |

Helpmann Awards

[edit]The Helpmann Awards is an awards show, celebrating live entertainment and performing arts in Australia, presented by industry group Live Performance Australia (LPA) since 2001.[101] In 2018, Roach received the JC Williamson Award, the LPA's highest honour, for their life's work in live performance.

| Year | Nominee / work | Award | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2005[102] | Kura Tungar: Songs from the River (with Ruby Hunter) | Best Australian Contemporary Concert | Won |

| 2013[103] | Into the Bloodstream | Best Australian Contemporary Concert | Nominated |

| 2018 | Himself | JC Williamson Award | awarded |

J Awards

[edit]The J Awards are an annual series of Australian music awards that were established by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation's youth-focused radio station Triple J. They commenced in 2005.

| Year | Nominee / work | Award | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020[104][105] | Archie Roach | Double J Artist of the Year | Won |

Mo Awards

[edit]The Australian Entertainment Mo Awards (commonly known informally as the Mo Awards) were annual Australian entertainment industry awards. They recognised achievements in live entertainment in Australia from 1975 to 2016. Archie Roach won two awards in that time.[106]

| Year | Nominee / work | Award | Result (wins only) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1991 | Archie Roach | Folk Performer of the Year | Won |

| 1992 | Archie Roach | Folk Performer of the Year | Won |

Music Victoria Awards

[edit]The Music Victoria Awards are an annual awards night celebrating Victorian music.

| Year | Nominee / work | Award | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | himself | Best Indigenous Act | Nominated |

| himself | Best Male Artist | Nominated | |

| Into the Bloodstream | Best Folk Roots Album | Won | |

| 2015 | himself | Hall of Fame | inductee |

| 2017 | himself | Best Indigenous Act | Nominated |

National Dreamtime Awards

[edit]The National Dreamtime Awards are an annual celebration of Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander achievement in sport, arts, academia and community. They commenced in 2017.

| Year | Nominee / work | Award | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2018[109] | himself | Achievement award | Won |

National Indigenous Music Awards

[edit]The National Indigenous Music Awards (NIMA) recognise excellence, dedication, innovation and outstanding contribution in the Northern Territory music industry. They commenced in 2004.

| Year | Nominee / work | Award | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2013[110] | "himself" | Hall of Fame Inductee | Inductee |

| Into the Bloodstream | Album of the Year | Won | |

| Cover Art of the Year | Won | ||

| "Song to Sing" | Film Clip of the Year | Won | |

| Song of the Year | Nominated | ||

| 2018[111] | himself | Artist of the Year | Nominated |

| 2019[112][113] | "himself" | Artist of the Year | Nominated |

| The Concert Collection 2012–2018 | Album of the Year | Nominated | |

| 2020[114][115] | "himself" | Artist of the Year | Nominated |

| Tell Me Why | Album of the Year | Won | |

| 2022[60][116] | My Songs: 1989–2021 | Album of the Year | Nominated |

Sidney Myer Performing Arts Awards

[edit]The Sidney Myer Performing Arts Awards commenced in 1984 and recognise outstanding achievements in dance, drama, comedy, music, opera, circus and puppetry.

| Year | Nominee / work | Award | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2009[117][118] | Archie Roach (with Ruby Hunter) | Individual Award | awarded |

References

[edit]- ^ Taylor, Beth (2019). "Archie Roach Interview". National Film and Sound Archive of Australia.

- ^ Roach, Archie (1999). "Roach, Archie". HistorySmiths. Archived from the original on 23 January 2001. Retrieved 26 February 2014 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ a b "Archie Roach, Aboriginal musician, songwriter and artist, dead at 66 after 'a remarkable life'". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 30 July 2022. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ^ a b Archie Roach, His life story told through his music, National Film & Sound Archive

- ^ a b Roach, A. (2002) lyrics to "Move It On" on Sensual Being.

- ^ "Rumbalara: Our Story". Rumbalara Aboriginal Cooperative. 26 March 2018. Retrieved 2 August 2022 – via Issuu.

- ^ Rumbalara: Our Story (in Turkish). Inception Strategies and Rumbalara Aboriginal Cooperative. 2018. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- ^ "Archie's road". The Age. 25 August 2002. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- ^ Williams, Ben (24 March 2005). "Archie Roach: Sensual Being". Festival Mushroom Records. Archived from the original on 24 March 2005. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- ^ Monger, Timothy. "Archie Roach Biography, Songs, & Albums". AllMusic. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- ^ a b c d e "Archie Roach, 1992 (printed 2010)". portrait. 2010. Retrieved 28 September 2018.

- ^ a b "From stolen child to Indigenous leader: Archie Roach sings the songs that signpost his life". ABC. 12 July 2018. Retrieved 28 September 2018.

- ^ "Archie Roach | First Peoples – State Relations". www.firstpeoplesrelations.vic.gov.au. 30 September 2019. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- ^ Marsh, Walter (3 November 2019). "Archie Roach tells his story right and true in memoir Tell Me Why". The Adelaide Review. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

- ^ a b Cooper, Nathanael (10 November 2020). "'It is a great honour': Archie Roach to be inducted into ARIA hall of fame". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- ^ Archie Roach's first big concert with Paul Kelly, Talking Heads, 2008 at National Film and Sound Archive of Australia

- ^ a b "Archie Roach Receives Ted Albert Award". APRA AMCOS. 27 March 2017. Retrieved 28 September 2018.

- ^ "Archie Roach's song: 'Took the Children Away'". Rumington. July 2014. Retrieved 28 September 2018.

- ^ Annual Report 1990-1991, Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission

- ^ a b "Artist Archie Roach". ABC. 2010. Archived from the original on 28 September 2018. Retrieved 28 September 2018.

- ^ Ryan, Gavin (2011). Australia's Music Charts 1988–2010 (pdf ed.). Mt. Martha, VIC, Australia: Moonlight Publishing. p. 237.

- ^ "Archie Roach Deadly". Deadly. November 2007. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- ^ "ARIA Awards – History: Winners by Year 1997". Australian Recording Industry Association (ARIA). Retrieved 24 September 2018.

- ^ "Winners by Year 1998". Australian Recording Industry Association (ARIA). Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- ^ "The Tracker". Vertigo Productions. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ^ a b "Ruby's Story". Sydney Morning Herald. 7 June 2004. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- ^ "Archie Roach & Ruby Hunter". Deadly Vibe. November 2007. Archived from the original on 12 April 2020.

- ^ "Ruby's Story". Australian Art Story. Archived from the original on 26 February 2020.

- ^ "Ruby (DD)". iTunes Australia. January 2005. Retrieved 8 October 2018.

- ^ a b c "About the film". Wash My Soul Film. Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- ^ "Melbourne Festival: 08-25 October". Melbourne Festival. Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- ^ "Wash My Soul in the Rivers Flow". Documentary Australia. 3 August 2020. Retrieved 16 July 2023.

- ^ "Archie Roach – Journey Archie's 2007 Studio Album on CD". Captain Stomp. Archived from the original on 28 September 2018. Retrieved 28 September 2018.

- ^ "Dirtsong". AustLit. 24 October 2009. Retrieved 19 October 2022.

- ^ "Dirtsong" (audio). The Wire. 28 April 2016. Retrieved 19 October 2022.

- ^ McDonald, Patrick (17 March 2014). "Adelaide Festival review 2014: Dirtsong – Black Arm Band". Adelaide Now.

- ^ Johnson, Dash Taylor (16 March 2014). "Black Arm Band: dirtsong". InDaily. Retrieved 19 October 2022.

- ^ "Music Deli Presents Archie Roach 1988". ABC Music. 2009. Archived from the original on 13 October 2018. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- ^ "Out of the pain, a spirit rises". SMH. 19 October 2010. Retrieved 28 September 2018.

- ^ a b c "Deadly Archie wants action from Abbott". Sydney Morning Herald. 10 September 2013. Retrieved 28 September 2018.

- ^ "ARCHIE ROACH 4CD SET 'CREATION' IS OUT NOW!". Facebook. 3 October 2013. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- ^ "2015 SCREEN MUSIC AWARDS". APRA AMCOS. 2015. Retrieved 28 September 2018.

- ^ "Charcoal Lane (25th Anniversary Edition)". JBHiFi. Retrieved 28 September 2018.

- ^ "Archie Roach – Let Love Rule (album)". Australian-charts.com. Retrieved 31 July 2022.

- ^ "Commonwealth Games closing ceremony a disastrous finish to a brilliant event". Courier Mail. 15 April 2018. Retrieved 28 September 2018.

- ^ "National Indigenous Music Awards unveils 2019 Nominations". National Indigenous Music Awards. July 2019. Retrieved 19 August 2019.

- ^ Roach, Archie (1 November 2019). Tell Me Why: The Story of My Life and My Music. Simon & Schuster Australia. ISBN 978-1-76085-016-6. Retrieved 1 August 2022.

- ^ a b "Archie Roach Has A Companion Album For His New Book". noise11. 25 September 2019. Retrieved 28 September 2019.

- ^ a b "2020 Victorian Premier's Literary Awards shortlists announced". Books+Publishing. 2 December 2019. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- ^ "Australian Independent Bookseller – News & Features". Australian Independent Bookseller. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- ^ "'Phosphorescence' wins 2021 ABIA Book of the Year". Books+Publishing. 28 April 2021. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- ^ "Wash My Soul in the River's Flow (2022) – The Screen Guide". Screen Australia. Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- ^ Wash My Soul in the River's Flow at IMDb

- ^ Dow, Steve (15 February 2022). "Archie Roach on meeting, loving and losing Ruby Hunter: 'She had this glint in her eye'". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ "Wash My Soul in the River's Flow". Brisbane International Film Festival. 30 September 2021. Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- ^ "Home". Wash My Soul Film. Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- ^ "Wash My Soul in the River's Flow (2021) – 6 & 7 Dec Music on Film". Australian Centre for the Moving Image. 11 November 2021. Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- ^ "Archie Roach to release career-spanning anthology, shares stunning new song". ABC. 11 February 2022. Retrieved 13 February 2022.

- ^ "Singles Chart (Independent Labels) 21 March 2022". Australian Independent Record Labels Association. 21 March 2022. Retrieved 31 July 2022.

- ^ a b "Nominees and Performers Announced For National Indigenous Music Awards 2022". Music Feeds. 13 July 2022. Retrieved 14 July 2022.

- ^ "An Epic Set of Performers Announced for the 2022 ARIA Awards". Australian Recording Industry Association (ARIA). 16 November 2022. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ^ "Songs from the Kitchen Table: Lyrics and Stories". Neighbourhood Books. 2023. Retrieved 2 June 2024.

- ^ a b c d Williamson, Bhiamie (31 July 2022). "Archie Roach: the great songman, tender and humble, who gave our people a voice". The Conversation. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- ^ "Aboriginal singer Archie Roach recovering from stroke". Daily Telegraph. 16 October 2010. Retrieved 28 September 2018.

- ^ "Archie Roach suffers a stroke". The Sydney Morning Herald. 15 October 2010. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- ^ "Into the Bloodstream, Archie Roach". ABC. 5 November 2012. Retrieved 28 September 2018.

- ^ Dalton, Angus (30 July 2022). "Singer-songwriter Archie Roach dead aged 66". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ^ "'Thank you for the truth, and singing what you lived': Australia pays tribute to Archie Roach". Double J. 31 July 2022. Retrieved 31 July 2022.

- ^ Landau, Sophie (3 May 2022). "Monuments honouring Aunty Ruby Hunter and Uncle Archie Roach inspires next generation". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- ^ Yu, Andi (30 November 2024). "Statues of music legends Archie Roach and Ruby Hunter unveiled at a Melbourne park". ABC News. Retrieved 1 December 2024.

- ^ "Bhiamie Williamson". The Conversation. 7 January 2020. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- ^ "About the Foundation". Archie Roach. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- ^ "Meet our team". Archie Roach. Archived from the original on 31 July 2022. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- ^ "2011 Victorian Aboriginal Honour Roll". www.vic.gov.au. Archived from the original on 8 November 2018. Retrieved 8 November 2018.

- ^ "Queens Birthday honours 2015: full list". 8 June 2015.

- ^ "Victoria Australian of the Year Award". Australian of the Year Awards 2020. 2020. Archived from the original on 21 March 2020. Retrieved 9 August 2020.

- ^ "Australia Day 2023 Honours: Full list". The Sydney Morning Herald. 25 January 2023. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- ^ "National Film and Sound Archive". Sounds of Australia. Retrieved 28 September 2018.

- ^ "A.B Original dominates 2017 AIR Awards nominations". theindustryobserver. 31 May 2017. Retrieved 20 August 2020.

- ^ "History Wins". Australian Independent Record Labels Association. Retrieved 18 August 2020.

- ^ "APRA History". Australasian Performing Right Association (APRA) | Australasian Mechanical Copyright Owners Society (AMCOS). Retrieved 25 April 2022.

- ^ Brandle, Lars (27 March 2017). "Archie Roach to Receive Australia's Ted Albert Award". Billboard. Retrieved 7 April 2017.

- ^ "Ted Albert Award for Outstanding Services to Australian Music". Australasian Performing Right Association (APRA) | Australasian Mechanical Copyright Owners Society (AMCOS). 2017. Retrieved 7 April 2017.

- ^ "Shortlist announced for 2017 APRA Song of the Year". The Music Network. January 2017. Retrieved 15 April 2022.

- ^ "APRA Has Revealed The 2020 Song Of The Year Finalists". The Music. 6 February 2020. Retrieved 26 April 2022.

- ^ "One of these songs will be the Peer-Voted APRA Song of the Year!". APRA AMCOS. 3 February 2021. Retrieved 26 April 2022.

- ^ "These 20 songs are up for 2023 APRA Song Of The Year". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 25 January 2023. Retrieved 28 January 2023.

- ^ "ARIA Awards – History". Australian Record Industry Association. Retrieved 6 April 2016.

- ^ Kelly, Vivienne (20 October 2021). "ARIA Awards nominees revealed: Amy Shark & Genesis Owusu lead the charge". The Music Network. Archived from the original on 20 October 2021. Retrieved 24 October 2021.

- ^ Lars Brandle (12 October 2022). "Rüfüs Du Sol Leads 2022 ARIA Awards Nominees (Full List)". The Music Network. Retrieved 12 October 2022.

- ^ Newstead, Al (24 November 2022). "ARIA Awards 2022 Winners Wrap: Baker Boy Leads First Nations Sweep". Triple J (Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC)). Retrieved 25 November 2022.

- ^ "Archie Roach honoured with Red Ochre award". ABC News. 26 May 2011. Retrieved 31 July 2022.

- ^ "Deadly's 1997". Vibe Australia. 18 June 2004. Archived from the original (web.archive.org) on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 31 July 2022.

- ^ "Deadly's 1998". Vibe Australia. 17 June 2004. Archived from the original (web.archive.org) on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 31 July 2022.

- ^ "The 2002 Deadlys". Vibe Australia. 20 July 2008. Archived from the original (web.archive.org) on 20 July 2008. Retrieved 31 July 2022.

- ^ "The 2003 Deadlys". Vibe Australia. 20 July 2008. Archived from the original (web.archive.org) on 20 July 2008. Retrieved 31 July 2022.

- ^ "The 2004 Deadlys". 21 July 2008. Archived from the original (web.archive.org) on 21 July 2008. Retrieved 31 July 2022.

- ^ "2010 Deadly Award Winners". Vibe Australia. 11 February 2011. Archived from the original (web.archive.org) on 11 February 2011. Retrieved 31 July 2022.

- ^ "Don Banks Music Award: Prize". Australian Music Centre. Archived from the original on 18 August 2015. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ^ Northover, Kylie (8 March 2015). "Australia Council Awards honour Archie Roach, Bruce Gladwin and Stelarc". The Age. Retrieved 31 July 2022.

Indigenous singer Archie Roach was awarded the Don Banks Music Award for a "distinguished artist over age 50 who has made an outstanding and sustained contribution to music". Roach, who continues to play concerts despite recent health problems, said it was "quite an honour". "This is a big one. It's very prestigious. Don Banks was the first chair of the music board of the Australia Council so it's a real honour," he said on Sunday.

- ^ "Events & Programs". Live Performance Australia. Retrieved 17 August 2022.

- ^ "2005 Helpmann Awards winners list - Entertainment". Sydney Morning Herald. 9 August 2005. Retrieved 12 July 2016.

- ^ "2013 Helpmann Awards Nominees & Winners". Helpmann Awards. Australian Entertainment Industry Association (AEIA). Retrieved 8 October 2022.

- ^ "Here are your nominees for the 2020 J Awards!". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 2 November 2020. Retrieved 3 November 2020.

- ^ Triscari, Caleb (19 November 2020). "Lime Cordiale take home Australian Album of the Year at the 2020 J Awards". NME Australia. Retrieved 19 November 2020.

- ^ "MO Award Winners". Mo Awards. Retrieved 16 March 2022.

- ^ "Previous Nominess". Music Victoria. Archived from the original on 19 September 2020. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- ^ "Previous Winners". Music Victoria. Archived from the original on 31 July 2019. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- ^ "Dream of love, and success will come" (PDF). AIATSIS – The Koori Mail. 28 November 2018. pp. 32–34. Archived from the original (web.archive.org) on 21 December 2019. Retrieved 31 July 2022.

- ^ "2013 Winners – National Indigenous Music Awards". nima.musicnt.com.au. web.archive.org. Archived from the original on 4 March 2020. Retrieved 31 July 2022.

- ^ "2018 National Indigenous Music Award Winners". National Indigenous Music Awards. NIMA. 26 March 2019. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ^ "National Indigenous Music Awards unveils 2019 Nominations". National Indigenous Music Awards. July 2019. Retrieved 19 August 2019.

- ^ "Record Breaking Crowd for the 2019 National Indigenous Music Awards!". National Indigenous Music Awards. 13 August 2019. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ^ "Announcement: National Indigenous Music Awards Finalists Unveiled". noise11. 13 July 2020. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- ^ "2020 Finalists". NIMA. July 2020. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- ^ "2022 NIMAs: Baker Boy Wins Two Awards, Archie Roach and Gurrumul Honoured". The Music Network. 6 August 2022. Retrieved 7 August 2022.

- ^ "Ruby Hunter, b. 1955". National Portrait Gallery (Australia) people. 2018. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- ^ Beaumont, Lucy (27 March 2009). "Rich award no hoax for Archie and Ruby". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Archie Roach: His life story told through his music at the National Film and Sound Archive

- Archie Roach at allmusic.com

- Archie Roach discography at Discogs

- Archie Roach at IMDb

- "A Conversation with Archie Roach and Ruby Hunter" (Audio). Radio Netherlands Archives. 4 November 2004.

- 1956 births

- 2022 deaths

- Companions of the Order of Australia

- APRA Award winners

- ARIA Award winners

- Australian guitarists

- Australian male singers

- Australian male songwriters

- Indigenous Australian musicians

- Members of the Stolen Generations

- Storytellers

- People from Mooroopna

- Mushroom Records artists

- Australian male guitarists

- Australian autobiographers

- ARIA Hall of Fame inductees