United States Africa Command

| United States Africa Command | |

|---|---|

Emblem of United States Africa Command | |

| Active | Established: 1 October 2007 (17 years, 5 months) Activated: 1 October 2008 (16 years, 5 months)[1] |

| Country | |

| Type | Unified combatant command |

| Role | Geographic combatant command |

| Size | 2,000 (1,500 stationed at HQ in Germany)[2] |

| Part of | |

| Headquarters | Kelley Barracks, Stuttgart, Germany |

| Nickname(s) | U.S. AFRICOM, USAFRICOM |

| Engagements | |

| Website | www.africom.mil |

| Commanders | |

| Commander | General Michael E. Langley, USMC |

| Deputy Commander | Lieutenant General John W. Brennan, USA |

| Deputy to the Commander for Civil-Military Engagement | Ambassador Andrew Young, DOS |

| Senior Enlisted Leader | Sergeant Major Michael P. Woods, USMC |

| Insignia | |

| NATO Map Symbol[3] |  |

The United States Africa Command (USAFRICOM, U.S. AFRICOM, and AFRICOM)[4] is one of the eleven unified combatant commands of the United States Department of Defense, headquartered at Kelley Barracks, Stuttgart, Germany. It is responsible for U.S. military operations, including fighting regional conflicts[5] and maintaining military relations with 53 African nations. Its area of responsibility covers all of Africa except Egypt, which is within the area of responsibility of the United States Central Command. U.S. AFRICOM headquarters operating budget was $276 million in fiscal year 2012.[2]

| United States Armed Forces |

|---|

|

| Executive departments |

| Staff |

| Military departments |

| Military services |

| Command structure |

The Commander of U.S. AFRICOM reports to the Secretary of Defense.[6] The current Commander of the U.S. Africa Command stated that the purpose of the command is to work alongside African military personnel to support their military operations.[7] In individual countries, U.S. ambassadors continue to be the primary diplomatic representative for relations with host nations. The incumbent commander is Michael E. Langley.

History

[edit]Origins

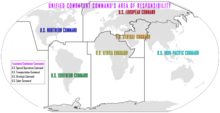

[edit]Prior to the creation of AFRICOM, responsibility for U.S. military operations in Africa was divided across three unified commands: United States European Command (EUCOM) for West Africa, United States Central Command (CENTCOM) for East Africa, and United States Pacific Command (PACOM) for Indian Ocean waters and islands off the east coast of Africa.

A U.S. military officer wrote the first public article calling for the formation of a separate African command in November 2000.[8] Following a 2004 global posture review, the United States Department of Defense began establishing a number of Cooperative Security Locations (CSLs) and Forward Operating Sites (FOSs) across the African continent, through the auspices of EUCOM which had nominal command of West Africa at that time. These locations, along with Camp Lemonnier in Djibouti, would form the basis of AFRICOM facilities on the continent. Areas of military interest to the United States in Africa include the Sahara/Sahel region,[9] over which Joint Task Force Aztec Silence is conducting anti-terrorist operations (Operation Enduring Freedom - Trans Sahara), Djibouti in the Horn of Africa, where Combined Joint Task Force – Horn of Africa is located (overseeing Operation Enduring Freedom - Horn of Africa), and the Gulf of Guinea.

The website Magharebia.com was launched by USEUCOM in 2004 to provide news about North Africa in English, French and Arabic.[10] When AFRICOM was created, it took over operation of the website.[11] Information operations of the United States Department of Defense was criticized by the Senate Armed Forces Committee and defunded by Congress in 2011. The site was closed down in February 2015.[12][13]

In 2007, the United States Congress approved $500 million for the Trans-Saharan Counterterrorism Initiative (TSCTI) over six years to support countries involved in counterterrorism against threats of Al Qaeda operating in African countries, primarily Algeria, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Senegal, Nigeria, and Morocco.[14] This program builds upon the former Pan Sahel Initiative (PSI), which concluded in December 2004[15] and focused on weapon and drug trafficking, as well as counterterrorism.[16] Previous U.S. military activities in Sub-Saharan Africa have included Special Forces associated Joint Combined Exchange Training. Letitia Lawson, writing in 2007 for a Center for Contemporary Conflict journal at the Naval Postgraduate School, noted that U.S. policy towards Africa, at least in the medium-term, looks to be largely defined by international terrorism, the increasing importance of African oil to American energy needs, and the dramatic expansion and improvement of Sino-African relations since 2000.[17]

Creation of the command (2006–2008)

[edit]In mid-2006, Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld formed a planning team to advise on requirements for establishing a new Unified Command for the African continent. In early December, he made his recommendations to President George W. Bush.[18][19]

On 6 February 2007, Defense Secretary Robert Gates announced to the Senate Armed Services Committee that President George W. Bush had given authority to create the new African Command.[20] U.S. Navy Rear Admiral Robert Moeller, the director of the AFRICOM transition team, arrived in Stuttgart, Germany to begin creating the logistical framework for the command.[21][22] The creation of the command was introduced to African military leaders by General William E. "Kip" Ward who traveled to various African countries.[7] On 28 September, the U.S. Senate confirmed General Ward as AFRICOM's first commander and AFRICOM officially became operational as a sub-unified command of EUCOM with a separate headquarters.[23] On 1 October 2008 became a fully operational command and incorporated pre-existing entities, including the Combined Joint Task Force - Horn of Africa that was created in 2002.[7] At this time, the command also separated from USEUCOM and began operating on its own as a full-fledged combatant command.

Function

[edit]In 2007, the White House announced that Africa Command "will strengthen our security cooperation with Africa and create new opportunities to bolster the capabilities of our partners in Africa. Africa Command will enhance our efforts to bring peace and security to the people of Africa and promote our common goals of development, health, education, democracy, and economic growth in Africa."[24]

General Carter F. Ham said in a 2012 address at Brown University that U.S. strategy for Sub-Saharan Africa is to strengthen democratic institutions and boost broad-based economic growth.[2]

In 2017 the U.S. Africa Command was operating along five lines of effort:

- Neutralize al-Shabaab and transition the security responsibilities of the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) to the Federal Government of Somalia (FGS)

- Degrade violent extremist organizations in the Sahel Maghreb and contain instability in Libya

- Contain and degrade Boko Haram

- Interdict illicit activity in the Gulf of Guinea and Central Africa with willing and capable African partners

- Build peacekeeping, humanitarian assistance and disaster response capacity of African partners[25]

On 18 March 2019, AFRICOM conducted an airstrike over Mogadishu, Somalia aimed at "the terrorist network and its recruiting efforts in the region", specifically referencing al-Shabaab. AFRICOM reported that the number of terrorists killed by this airstrike was 3, but this fact, as well as how many civilian casualties there were is still under dispute.[26]

Area of responsibility

[edit]

The territory of the command consists of all of the African continent except for Egypt, which remains under the responsibility of Central Command, as it closely relates to the Middle East. USAFRICOM also covers island countries commonly associated with Africa:

The U.S. military areas of responsibility involved were transferred from three separate U.S. unified combatant commands. Most of Africa was transferred from the United States European Command with the Horn of Africa and Sudan transferred from the United States Central Command. Responsibility for U.S. military operations in the islands of Madagascar, the Comoros, the Seychelles and Mauritius was transferred from the United States Pacific Command.

Headquarters and facilities

[edit]The AFRICOM headquarters is located at Kelley Barracks, a small urban facility near Stuttgart, Germany, and is staffed by 1,500 personnel. In addition, the command has military and civilian personnel assigned at Camp Lemonnier, Djibouti; RAF Molesworth, United Kingdom; MacDill Air Force Base, Florida; and in Offices of Security Cooperation and Defense Attaché Offices in about 38 African countries.[2]

Selection of the headquarters

[edit]It was reported in June 2007 that African countries were competing to host the headquarters because it would bring money for the recipient country.[28] Liberia has publicly expressed a willingness to host AFRICOM's headquarters, and in 2021 Nigeria expressed a similar interest.[29] The U.S. declared in February 2008 that AFRICOM would be headquartered in Stuttgart for the "foreseeable future". In August 2007, Dr. Wafula Okumu, a research fellow at the Institute for Security Studies in South Africa, testified before the United States Congress about the growing resistance and hostility on the African continent.[30] Nigeria announced it will not allow its country to host a base and opposed the creation of a base on the continent. South Africa and Libya also expressed reservations of the establishment of a headquarters in Africa.[31][32]

The Sudan Tribune considered it likely that Ethiopia, a strong U.S. ally in the region, will house USAFRICOM's headquarters due to the collocation of AFRICOM with the African Union's developing peace and security apparatus.[33] Prime Minister Meles Zenawi stated in early November that Ethiopia would be willing to work together closely with USAFRICOM.[34] This was further reinforced when a U.S. Air Force official said on 5 December 2007, that Addis Ababa was likely to be the headquarters.[35]

On 18 February 2008, General Ward told an audience at the Royal United Services Institute in London that some portion of that staff headquarters being on the continent at some point in time would be "a positive factor in helping us better deliver programs."[36] General Ward also told the BBC the same day in an interview that there are no definite plans to take the headquarters or a portion of it to any particular location on the continent.[37]

President Bush denied that the United States was contemplating the construction of new bases on the African continent.[38] U.S. plans include no large installations such as Camp Bondsteel in Kosovo, but rather a network of "cooperative security locations" at which temporary activities will be conducted. There is one U.S. base on the continent, Camp Lemonnier in Djibouti, with approximately 2,300 troops stationed there having been inherited from USCENTCOM upon standup of the command.

In general, U.S. Unified Combatant Commands have an HQ of their own in one location, subordinate service component HQs, sometimes one or two co-located with the main HQ or sometimes spread widely, and a wide range of operating locations, main bases, forward detachments, etc. USAFRICOM initially appears to be considering something slightly different; spreading the actually COCOM HQ over several locations, rather than having the COCOM HQ in one place and the putative "U.S. Army Forces, Africa", its air component, and "U.S. Naval Forces, Africa" in one to four separate locations. AFRICOM will not have the traditional J-type staff divisions,[clarification needed] instead having outreach, plans and programs, knowledge development, operations and logistics, and resources branches.[39] AFRICOM went back to a traditional J-Staff in early 2011 after General Carter Ham took command.[40]

In the summer of 2020, U.S. Defense Secretary Mark Esper directed AFRICOM leadership to study a possible headquarters relocation outside of Germany after plans were announced that neighboring U.S. European Command would relocate to Belgium.[41]

On 20 November 2020 a new Army service component command (ASCC), U.S. Army Europe and Africa (USAREUR-AF) consolidated USAREUR and USARAAF.[42] The U.S. Army Africa/Southern European Task Force is now the U.S. Army Southern European Task Force, Africa (SETAF-AF).[42]

Personnel

[edit]U.S. Africa Command completed fiscal year 2010 with approximately 2,000 assigned personnel, which includes military, civilian, contractor, and host nation employees. About 1,500 work at the command's main headquarters in Stuttgart. Others are assigned to the command's units in England and Florida, along with security cooperation officers posted at U.S. embassies and diplomatic missions in Africa to coordinate Defense Department programs within the host nation.

As of December 2010, the command has five Senior Foreign Service officers in key positions as well as more than 30 personnel from 13 U.S. Government Departments and Agencies serving in leadership, management, and staff positions. Some of the agencies represented are the United States Departments of State, Treasury, and Commerce, United States Agency for International Development, and the United States Coast Guard.

U.S. Africa Command has limited assigned forces and relies on the Department of Defense for resources necessary to support its missions.

Components

[edit]On 1 October 2008, the Seventeenth Air Force was established at Ramstein Air Base, Germany as the United States Air Force component of the Africa Command.[43] Brig. Gen. Tracey Garrett was named as commander of the new USMC component, U.S. Marine Corps Forces Africa (MARFORAF), in November 2008.[44][45] MARFORAF is a dual-mission arrangement for United States Marine Corps Forces, Europe.

On 3 December 2008, the U.S. announced that Army and Navy headquarters units of AFRICOM would be hosted in Italy. The AFRICOM section of the Army's Southern European Task Force would be located in Vicenza and Naval Forces Europe in Naples would expand to include the Navy's AFRICOM component.[46] Special Operations Command, Africa (SOCAFRICA) is also established, gaining control over Joint Special Operations Task Force-Trans Sahara (JSOTF-TS) and Special Operations Command and Control Element – Horn of Africa (SOCCE-HOA).[47]

The U.S. Army has allocated a brigade to the Africa Command.[48]

U.S. Army Europe and Africa (USAREUR-AF)

[edit]

Headquartered on Lucius D. Clay Kaserne in Wiesbaden, Germany, U.S. Army Europe and Africa — Southern European Task Force - Africa (SETAF-AF), in concert with national and international partners, conducts sustained security engagement with African land forces to promote peace, stability, and security in Africa. As directed, it can deploy as a contingency headquarters in support of crisis response.[49] The commander of SETAF-AF is DCG for Africa.

As of March 2013, the 2nd Brigade Combat Team, 1st Infantry Division, the "Dagger Brigade", is being aligned with AFRICOM.[50]

U.S. Naval Forces Africa (NAVAF)

[edit]

U.S. Naval Forces Europe - Naval Forces Africa (NAVEUR-NAVAF) area of responsibility (AOR) covers approximately half of the Atlantic Ocean, from the North Pole to Antarctica; as well as the Adriatic, Baltic, Barents, Black, Caspian, Mediterranean and North Seas.[51] NAVEUR-NAVAF covers all of Russia, Europe and nearly the entire continent of Africa. It encompasses 105 countries with a combined population of more than one billion people and includes a landmass extending more than 14 million square miles.

The area of responsibility covers more than 20 million square nautical miles of ocean, touches three continents and encompasses more than 67 percent of the Earth's coastline, 30 percent of its landmass, and nearly 40 percent of the world's population.[52]

Task Force 60 will normally be the commander of Naval Task Force Europe and Africa.[citation needed] Any naval unit within the USEUCOM or USAFRICOM AOR may be assigned to Task Force 60 as required upon by the Commander of the Sixth Fleet.

Air Forces Africa (AFAFRICA)

[edit]

Air Forces Africa (AFAFRICA) is located at Ramstein Air Base, Germany, and serves as the air and space component to U.S. Africa Command (AFRICOM) located at Stuttgart, Germany. Air Forces Africa shares a headquarters and units with United States Air Forces in Europe, and its component Air Force, 3AF (AFAFRICA) conducts sustained security engagement and operations as directed to promote air safety, security and development on the African continent. Through its Theater Security Cooperation (TSC) events, Air Forces Africa carries out AFRICOM's policy of seeking long-term partnership with the African Union and regional organizations as well as individual nations on the continent.[53]

Air Forces Africa works with other U.S. Government agencies, to include the State Department and the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), to assist African partners in developing national and regional security institution capabilities that promote security and stability and facilitate development.[54]

3AF succeeds the Seventeenth Air Force by assuming the AFAFRICA mission upon the 17AF's deactivation on 20 April 2012.[55]

U.S. Marine Corps Forces, Africa (MARFORAF)

[edit]

U.S. Marine Corps Forces, Africa conducts operations, exercises, training, and security cooperation activities throughout the AOR. In 2009, MARFORAF participated in 15 ACOTA missions aimed at improving partners' capabilities to provide logistical support, employ military police, and exercise command and control over deployed forces.

MARFORAF conducted military to military events in 2009 designed to familiarize African partners with nearly every facet of military operations and procedures, including use of unmanned aerial vehicles, tactics, and medical skills. MARFORAF, as the lead component, continues to conduct Exercise AFRICAN LION in Morocco—the largest annual Combined Joint Chiefs of Staff (CJCS) exercise on the African continent—as well as Exercise SHARED ACCORD 10, which was the first CJCS exercise conducted in Mozambique.[56]

In 2013, the Special Purpose Marine Air-Ground Task Force - Crisis Response - Africa was formed to provide quick response to American interests in North Africa by flying marines in Bell Boeing V-22 Osprey aircraft from bases in Europe.[57]

Subordinate Commands

[edit]U.S. Special Operations Command Africa

[edit]

Special Operations Command Africa was activated on 1 October 2008 and became fully operationally capable on 1 October 2009. SOCAFRICA is a Subordinate-Unified Command of United States Special Operations Command, operationally controlled by U.S. Africa Command, collocated with USAFRICOM at Kelley Barracks, Stuttgart-Möhringen, Germany. Also on 1 October 2008, SOCAFRICA assumed responsibility for the Special Operations Command and Control Element – Horn of Africa, and on 15 May 2009, SOCAFRICA assumed responsibility for Joint Special Operations Task Force Trans – Sahara (JSOTF-TS) – the SOF component of Operation Enduring Freedom – Trans Sahara.

SOCAFRICA's objectives are to build operational capacity, strengthen regional security and capacity initiatives, implement effective communication strategies in support of strategic objectives, and eradicate violent extremist organizations and their supporting networks. SOCAFRICA forces work closely with both U.S. Embassy country teams and African partners, maintaining a small but sustained presence throughout Africa, predominantly in the OEF-TS and CJTF-HOA regions. SOCAFRICA's persistent SOF presence provides an invaluable resource that furthers USG efforts to combat violent extremist groups and builds partner nation CT capacity.[58]

On 8 April 2011, Naval Special Warfare Unit 10, operationally assigned and specifically dedicated for SOCAFRICA missions, was commissioned at Panzer Kaserne, near Stuttgart, Germany.[59] It is administratively assigned to Naval Special Warfare Group 2 on the U.S. East Coast.

Organizations included in SOCAFRICA include:[60]

- Special Operations Command Forward—East (Special Operations Command and Control Element—Horn of Africa)

- Special Operations Command Forward—Central (AFRICOM Counter—Lord's Resistance Army Control Element)

- Special Operations Command Forward—West (Joint Special Operations Task Force—Trans Sahara)

- Naval Special Warfare Unit 10, Joint Special Operations Air Component Africa, and SOCAFRICA Signal Detachment

- Commander SOCAFRICA serves as the special operations adviser to commander, USAFRICOM.

Combined Joint Task Force – Horn of Africa

[edit]

Combined Joint Task Force – Horn of Africa (CJTF-HOA) conducts operations in the East Africa region to build partner nation capacity in order to promote regional security and stability, prevent conflict, and protect U.S. and coalition interests. CJTF-HOA's efforts, as part of a comprehensive whole-of-government approach, are aimed at increasing African partner nations' capacity to maintain a stable environment, with an effective government that provides a degree of economic and social advancement for its citizens.[61][62][63]

Programs and operations

[edit]The programs conducted by AFRICOM, in conjunction with African military forces focus on reconnaissance and direct action. However, AFRICOM's directives are to keep American military forces out of direct combat as best as possible. Despite this, the United States has admitted to American troops being involved in direct action during missions with African military partners, namely in classified 127e programs.[64][65] As of 2023, there have been at least 315 confirmed drone strikes from AFRICOM operations in Somalia. Estimates place the total number of deaths at least 1,668, with at least 33 civilians killed.[66][67] Each AFRICOM operations has a specific mission. Some of the operations in North and West Africa target ISIS, and Boko Haram. In East Africa, missions focus on targeting terrorist group Al-Shabaab and piracy.[65]

By country

[edit]Cameroon

[edit]Contingency Location Garoua is a United States Army base in Garoua, Cameroon used to support military operations against Boko Haram.[68] Approximately 200 personnel work at the site.[citation needed] The site is located adjacent to Cameroonian Air Force Base 301.[69]

Soldiers from the 10th Mountain Division were stationed at the base from October 2017.[citation needed] The task force provides security and logistics support for U.S. Africa Command's unmanned aerial vehicles, which gather intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance of nearby hot spots to help the Cameroonians locate and defeat the enemy.[70]

Djibouti

[edit]The largest number of US troops in Africa are in Djibouti and perform a counter terrorism mission.[71]

Somalia

[edit]The United States has roughly 400 troops in Somalia.[71] American military forces work closely with African Union troops. Troops conduct raids with Somali troops and provide transport. American forces have engaged in firefights in self-defense and drone airstrikes have been called in to provide additional support.[72]

Programs

[edit]- African Contingency Operations Training and Assistance

- Africa Partnership Station is the U.S. Africa Command's primary maritime security engagement program which strengthens maritime security through maritime training with various nations.

- Combating Terrorism Fellowship Program

- Pandemic Response Program

- State Partnership Program connects a U.S. state's National Guard to an African nation for military training and relationship-building.

- Diplomatic Engagement

- Conferences

- Military-to-Military Engagement

- National Guard State Partnership Program

- African Partnership Flight

- Africa Partnership Station

- African Maritime Law Enforcement Partnership

- Non-Commissioned Officer Development

- Logistics Engagement

- Military Intelligence

- Chaplain Engagement

- Women, Peace, and Security

Joint Exercise Programs

[edit]African Lion

[edit]Training exercises sponsored by the United States through AFRICOM and Morocco. Participants of this program came from Europe and Africa to undergo training in various military exercises and skills. Exercises conducted during African Lion included "command-and-control techniques, combat tactics, peacekeeping, and humanitarian assistance operations". Reported by AFRICOM to have improved the quality of operations conducted between the North African and United States military.[7]

Western Accord

[edit]Training exercises sponsored by AFRICOM, European, and Western African countries for the first time in 2014. The goal of this exercise was to improve African forces' skills in conducting peace support operations. An ebola epidemic occurring from 2014 to 2015 resulted in the exercises being hosted by the Netherlands. During this exercise the mission command for the "United Nation’s Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission" in Mali was replicated. Name of exercise changed to United Accord some time later.[7]

Central Accord

[edit]Training exercises conducted with the goal of increasing both the military knowledge and efficacy of collaborative interactions of the participating groups. Emphasis placed on crisis response tactics and fostering strong partnerships between participating groups. Forces came from Africa, the United States, and Europe. The Lake Chad Basin is an example of a regional mission conducted by The Multi-National Joint Task Force.[7]

Eastern Accord

[edit]Series of training exercises originally began in 1998 with a series of exercises titled "Natural Fire". The Justified Accord was a further continuation of the large group of exercises conducted under the name Eastern Accord. Participating forces came from the United States and various African allies. Conducted with the goal of improving coordinated operations in East Africa. Notable aspects of the training included discussion-based modules focused on peace-keeping endeavors.[7]

Southern Accord

[edit]Annual training exercise sponsored by AFRICOM in conjunction with allied African forces over several years. In 2014 partners also included the United Nation Integrated Training Service and U.S. Army Peacekeeping and Stability Operations Institute. Exercises focused around the goal of peacekeeping. In 2017, Southern Accord was renamed as United Accord.[7]

Cutlass Express

[edit]Series of training exercises held at sea off the coast of East Africa. The Cutlass Express series was conducted by the United States Naval Forces Africa, a group within AFRICOM. Exercises performed at this time focused on maritime security, piracy countermeasures and interception of prohibited cargo. Express series included operations Obangame Express, Saharan Express, and Phoenix Express.[7]

Obangame Express

[edit]Saharan Express

[edit]Phoenix Express

[edit]Flintlock

[edit]Silent Warrior

[edit]Africa Endeavor

[edit]Operations

[edit]- Armada Sweep - U.S. Navy electronic surveillance from ships off the coast of East Africa to support drone operations in the region[73]

- Echo Casemate - Support of French and African peacekeeping forces in the Central African Republic.[73]

- Operation Enduring Freedom - Horn of Africa

- Operation Enduring Freedom - Trans Sahara

- Exile Hunter - Training of Ethiopian forces for operations in Somalia

- Jukebox Lotus - Operations in Libya after attack on Benghazi Consulate.

- Junction Rain - Maritime security operations in the Gulf of Guinea.

- Junction Serpent - Surveillance operations of ISIS forces near Sirte, Libya

- Juniper Micron - Airlift of French forces to combat Islamic extremists in Mali

- Juniper Nimbus - Support for Nigerian Forces against Boko Haram

- Juniper Shield - Counterterrorism operations in northwest Africa[73]

- Jupiter Garrett – Joint Special Operations Command operation against high value targets in Somalia.

- Justified Seamount - Counter piracy operation off east African coast[73]

- Kodiak Hunter - Training of Kenyan forces for operations in Somalia[73]

- * Mongoose Hunter - Training of Somali forces for operations against Al Shabab[73]

- New Normal - Development of rapid response capability in Africa[73]

- Nimble Shield - Operation against Boko Haram and ISIS West Africa.[73]

- Oaken Sonnet I - 2013 rescue of United States personnel from South Sudan during its civil war[73]

- Oaken Sonnet II - 2014 operation in South Sudan

- Oaken Sonnet III – 2016 operation in South Sudan

- Oaken Steel - July 2016 to January 2017 deployment to Uganda and reinforcement of security forces at US embassy in South Sudan

- Objective Voice - Information operations and psychological warfare in Africa[73]

- Oblique Pillar - Contracted helicopter support for Somali National Army forces.[73]

- Operation Observant Compass.[74]

- Obsidian Lotus - Training Libyan special operations units[73]

- Obsidian Mosaic - Operation in Mali[73]

- Obsidian Nomad I - Counterterrorism operation in Diffa, Niger[73]

- Obsidian Nomad II - Counterterrorism operation in Arlit, Niger[73]

- Octave Anchor - Psychological warfare operations focused on Somalia.[73]

- Octave Shield - Operation by Combined Joint Task Force-Horn of Africa.[73]

- Octave Soundstage- Psychological warfare operations focused on Somalia.[73]

- Octave Stingray - Psychological warfare operations focused on Somalia.[73]

- Octave Summit - Psychological warfare operations focused on Somalia.[73]

- Operation Odyssey Dawn - Libya, was the first major combat deployment directed by Africa Command.[75]

- Operation Odyssey Lightning - Libya[76][73]

- Odyssey Resolve - Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance operations in area of Sirte, Libya.[73]

- Operation Onward Liberty - Liberia

- Paladin Hunter - Counterterrorism operation in Puntland.[73]

- RAINMAKER: A highly sensitive classified signals intelligence effort. Bases used: Chebelley, Djibouti; Baidoa, Baledogle, Kismayo and Mogadishu, Somalia[73]

- Ultimate Hunter - Counterterorism operation by US trained Kenyan force in Somalia[73]

- Operation Unified Protector - Libya

Contingency Operations

[edit]- Operation Odyssey Dawn

- Operation Juniper Micron

- Protection of U.S. Personnel and Facilities

- Operation United Assistance

- Operation Odyssey Lightning

Security Cooperation Operations

[edit]- Support to Peacekeeping Operations

- African Union Mission in Somalia

- Operation Observant Compass

- Counter-Boko Haram

- Africa Contingency Operations Training and Assistance

- Africa Deployment Assistance Partnership Team

- Counter-IED Training

- Foreign Military Sales

- International Military Education and Training

- Counter Narcotics

- Counter-Illicit Trafficking

- Medical Engagement

- Pandemic Response Program

- African Partner Outbreak Alliance

- West Africa Disaster Preparedness Initiative

- Veterinary Civil Action Program

List of commanders

[edit]

| No. | Commander | Term | Service branch | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Portrait | Name | Took office | Left office | Term length | ||

| 1 | General William E. Ward (born 1949) | 1 October 2007 | 9 March 2011 | 3 years, 159 days |  U.S. Army | |

| 2 | General Carter F. Ham (born 1952) | 9 March 2011 | 5 April 2013 | 2 years, 27 days |  U.S. Army | |

| 3 | General David M. Rodriguez (born 1954) | 5 April 2013 | 18 July 2016 | 3 years, 104 days |  U.S. Army | |

| 4 | General Thomas D. Waldhauser (born 1953) | 18 July 2016 | 26 July 2019 | 3 years, 8 days |  U.S. Marine Corps | |

| 5 | General Stephen J. Townsend (born 1959) | 26 July 2019 | 9 August 2022 | 3 years, 14 days |  U.S. Army | |

| 6 | General Michael E. Langley (born 1961/1962) | 9 August 2022 | Incumbent | 2 years, 229 days |  U.S. Marine Corps | |

References

[edit]- ^ "United States Africa Command". www.africom.mil.

- ^ a b c d "About the Command". U.S. AFRICOM. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ^ "ADP 1-02 Terms and Military Symbols" (PDF). US Army. 14 August 2018. pp. 4–8.

- ^ DOD Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms. U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) - Joint Chiefs of Staff - J7. August 2017. p. 372.

- ^ Mueller, Karl P. (8 July 2015). Precision and Purpose: Airpower in the Libyan Civil War. Rand Corporation. p. 83. ISBN 9780833087935.

- ^ "FACT SHEET: United States Africa Command". U.S. AFRICOM Office of Public Affairs. 15 April 2013. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i United States Africa Command: The First Ten Years. The United States Africa Command. 2018.

- ^ "A CINC for Sub-Saharan Africa? Rethinking the Unified Command Plan". Parameters. Winter 2000–01. US Army War College. Archived from the original on 9 November 2017. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- ^ Fellows, Catherine (8 August 2005). "US targets Sahara 'terrorist haven'". BBC News. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ^ "About This Site". 22 October 2004. Archived from the original on 4 December 2004.

- ^ Pincus, Walter (8 May 2015). "U.S. Africa Command Brings New Concerns". The Washington Post. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

- ^ Pincus, Walter (6 December 2011). "A speed bump for Pentagon's information ops". The Washington Post. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

- ^ Mazmanian, Adam (13 February 2015). "DOD shutters two 'influence' websites covering Africa". FCW. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

- ^ Lobe, Jim (31 January 2007). "POLITICS: Africa to Get Its Own U.S. Military Command". Inter Press Service. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ^ "Operations and Initiatives". EUCOM. Archived from the original on 9 January 2007. Retrieved 6 February 2007.

- ^ "Pan Sahel Initiative (PSI)". GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ^ Lawson, Letitia (January 2007). "U.S. Africa Policy Since the Cold War" (PDF). Strategic Insights. 6 (1). Department of National Security Affairs Center on Contemporary Conflict. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ^ Northham, Jackie (7 February 2007). "Pentagon Creates Military Command for Africa". NPR Morning Edition. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

- ^ Schogol, Jeff (30 December 2006). "Africa Command plans approved by Bush, DOD officials confirm". Stars and Stripes. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

- ^ Garamone, Jim (6 February 2007). "DoD Establishing U.S. Africa Command". American Forces Press Services. US Department of Defense. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

- ^ a b Crawley, Vince (6 February 2007). "U.S. Creating New Africa Command To Coordinate Military Efforts". USINFO. US Department of State. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

- ^ "Africa Command Transition Team leader arrives in Stuttgart". Africa Command Transition Team Public Affairs. USEUCOM. 27 February 2007. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

- ^ "U.S. Africa Command Reaches Initial Operating Capability". US AFRICOM Public Affairs. 1 October 2007. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

- ^ "President Bush Creates a Department of Defense Unified Combatant Command for Africa". Georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov. 6 February 2007. Retrieved 19 May 2011.

- ^ Waldhauser, General Thomas D. (9 March 2017). United States Africa Command 2017 Posture Statement (PDF). U.S. Senate Committee on Armed Services: U.S. Africa Command. p. 7.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Sperber, Amanda. "Does America Know Who Its Airstrike Victims Are?". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 7 November 2019.

- ^ Jelinek, Pauline (6 February 2007). "Pentagon setting up new U.S. command to oversee African missions". Independent Record. Associated Press. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

- ^ The Economist, "Policing the undergoverned spaces", 16–22 June 2007, p. 46

- ^ "Nigeria urges U.S. to move Africa Command headquarters to continent". Reuters. 27 April 2021.

- ^ "Africa: Testimony of Dr. Wafula Okumu – U.S. House Africom Hearing". Allafrica.com.

- ^ "US AFRICOM headquarters to remain in Germany for "foreseeable future". International Herald Tribune. 19 February 2008.

- ^ "US drops Africa military HQ plan". BBC News. 18 February 2008.

- ^ "US army boss for Africa says no garrisons planned". SudanTribune article. November 2007. Retrieved 19 May 2011.

- ^ "Ethiopia ready to cooperate with US Africa Command – Zenawi". SudanTribune article. November 2007. Retrieved 19 May 2011.

- ^ Erik Holmes, Official: AFRICOM Will Need Air Force Aircraft, Air Force Times, 5 December 2007

- ^ "TRANSCRIPT: General Ward Outlines Vision for U.S. Africa Command" Archived 7 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine, 18 February 2008

- ^ "TRANSCRIPT: AFRICOM's General Ward Interviewed by the BBC's Nick Childs" Archived 27 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine, 18 February 2008

- ^ "Bush Says No New U.S. Bases in Africa". Forbes.[dead link]

- ^ Stars and Stripes, AFRICOM to depart from J-code structure, 12 August 2007

- ^ (25 March 2020) General Officer Assignments "Maj. Gen. Joel K. Tyler, commanding general, U.S. Army Test and Evaluation Command, Aberdeen Proving Ground, Maryland, to director, J-3 Operations/Cyber, U.S. Africa Command, Germany"

- ^ Trump administration is considering moving U.S. Africa Command. It won’t be cheap or easy. Washington Post, 10 September 2020

- ^ a b U.S. Army Public Affairs (20 November 2020) U.S. Army Europe and Africa Commands consolidate

- ^ "U.S. AFRICOM Faces African Concerns – 10/01/07 17:39". DefenseNews.com. Retrieved 19 May 2011.[dead link]

- ^ Garrett, Brigadier General Tracy L.; Ward, General William E. (14 November 2008). "TRANSCRIPT: Marine Corps Forces, Africa Officially Established". Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 21 November 2008.

- ^ "U.S. Military Official Pays Courtesy Call" (Press release). The Executive Mansion, The Republic of Liberia. 18 November 2008. Archived from the original on 23 August 2009. Retrieved 21 November 2008.

- ^ Novak, Lisa M., "Italy To Host AFRICOM Headquarters", Stars and Stripes, 5 December 2008.

- ^ Special Operations Technology, Q & A with Brigadier General Patrick M. Higgins Archived 16 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Vol. 6, Issue 6, 2008

- ^ Lt. Gen. William Grisoli, "The Army has now aligned a brigade with U.S. Africa Command." accessdate=2012-12-10

- ^ "Welcome Information – US Army Africa". Usaraf.army.mil. Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 19 May 2011.

- ^ "Dagger brigade readies for AFRICOM missions". Army.mil. Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- ^ "Commander, U.S. Naval Forces Europe-Africa/U.S. 6th Fleet". Naveur-navaf.navy.mil. 21 December 2008. Retrieved 19 May 2011.

- ^ "CNE NAV Left Navigation". Naveur-navaf.navy.mil. 21 December 2008. Retrieved 19 May 2011.

- ^ "17th Air Force – Home". 17af.usafe.af.mil. Archived from the original on 10 May 2011. Retrieved 19 May 2011.

- ^ "17th Air Force – Home". Newpreview.afnews.af.mil. Archived from the original on 19 January 2016. Retrieved 19 May 2011.

- ^ "17th Air Force stands down, AFAFRICA mission carries on". U.S. Air Forces in Europe Public Affairs. Archived from the original on 26 May 2012. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- ^ "Mission". Marines.mil. 6 February 2007. Archived from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 19 May 2011.

- ^ "SP-MAGTF Crisis Response ACE maintains readiness 24/ 7". Marforaf.marines.mil. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- ^ "Report" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 19 May 2011.

- ^ "NSWU-10 Commissioning Provides SOCAFRICA Operational Flexibility on the African Continent". Archived from the original on 23 October 2014. Retrieved 23 October 2014.

- ^ SOCOM 2015 Factbook

- ^ "CJTF-HOA Factsheet". Hoa.africom.mil. Archived from the original on 26 April 2009. Retrieved 19 May 2011.

- ^ Election Shenanigans - Kenyan Hybrid Warfare (Book). ASIN B08DMZJ893.

- ^ Election Shenanigans - Kenyan Hybrid Warfare (Book). ASIN B08DGP72MH.

- ^ Morgan, Wesley (2 July 2018). "Behind the secret U.S. war in Africa". POLITICO. Retrieved 7 December 2019.

- ^ a b Turse, Nick (12 December 2018). "Exclusive: The U.S. has more military operations in Africa than the Middle East". Vice. Retrieved 7 December 2019.

- ^ "America's Counterterrorism Wars - The War in Somalia". New America. Archived from the original on 24 July 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ "Drone War: Somalia". The Bureau of Investigative Journalism. Retrieved 7 December 2019.

- ^ Myers, Meghann (22 February 2017). "Soldiers deploy to Central Africa to support the fight against Boko Haram". Army Times.

- ^ Turnipseed, Christina (24 November 2017). "Thanksgiving in Cameroon". United States Army.

Counted among the driven athletes; were members of Cameroon Air Force Base 301 right next door to CL Garoua.

- ^ "Isolated from US military, small Army post looks to rid terrorism in West Africa". CBC News. U.S. Army. 27 November 2017. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- ^ a b "Where does the U.S. have troops in Africa, and why?". Retrieved 24 October 2017.

- ^ "Inside the US military's mission in Somalia". ABC News. 5 May 2017. Retrieved 24 October 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y Turse, Nick; Naylor, Sean D. (17 April 2019). "Revealed: The U.S. military's 36 code-named operations in Africa". Yahoo! news. Retrieved 19 April 2019.

- ^ "EXCLUSIVE: Inside the Green Berets' hunt for brutal warlord". NBC News. 6 March 2017. Retrieved 1 May 2019.

- ^ Ham, Carter. "STATEMENT: AFRICOM Commander on Commencement of Military Strikes in Libya." AFRICOM, 19 March 2011.

- ^ "US AFRICOM ends military operation against IS radicals in Libya". Libyan Express. 21 December 2016. Retrieved 30 December 2016.

Further reading

[edit]- "AFRICOM Arrives", Jane's Defence Weekly, 1 October 2008

- McFate, Sean (January 2008). "US Africa Command: next step or next stumble?". African Affairs. 107 (426): 111–120. doi:10.1093/afraf/adm084.

- Al-Kassimi, K. (2017). The U.S informal empire: US African Command (AFRICOM) expanding the US economic-frontier by discursively securitizing Africa using exceptional speech acts. African Journal of Political Science and International Relations, 11(11), 301-316.

- Forest, James JF, and Rebecca Crispin. "AFRICOM: troubled infancy, promising future." Contemporary Security Policy 30, no. 1 (2009): 5-27. [1]

- http://library.rumsfeld.com/doclib/sp/3910/2006-02-06%20to%20Gen%20Pete%20Pace%20re%20Unified%20Command%20Plan.pdf - earliest Rumsfeld memo ("snowflake") at Rumsfeld.com identifiable re Africa command organization in 2006.

External links

[edit]- Official website and March 2010 posture statement

- United States Army Africa official website

- Africa Interactive Map from the United States Army Africa

- APCN (Africa Partner Country Network)

- "Advanced Questions for General William E. "Kip" Ward, U.S. Army Nominee for Commander, U.S. Africa Command" (PDF). (165 KB), U.S. Senate Committee on Armed Services testimony.

- "U.S. Africa Command: A New Strategic Paradigm?" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 February 2008. (1.03 MB) by Sean McFate in Military Review, January–February 2008

- Africa’s Security Challenges and Rising Strategic Significance, Strategic Insights, January 2007

- "AFRICOM public brief" (PDF). (652 KiB), United States Department of Defense, 2 February 2007

- "Blood Oil" by Sebastian Junger in Vanity Fair, February 2007. Retrieved 28 January 2007

- "Africa Command: 'Follow the oil'" in World War 4 Report, 16 February 2007

- The Americans Have Landed, Esquire, 27 June 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-10.

- Does Africa need Africom?

- ResistAFRICOM website

- Secret US Military Documents Reveal a Constellation of American Military Bases Across Africa

- Maps of Operation Enduring Freedom

- Trans-Sahara Counterterrorism Initiative Details of the operation by Global Security.