Venice, Los Angeles

Venice | |

|---|---|

Venice Beach and Boardwalk, 2005 | |

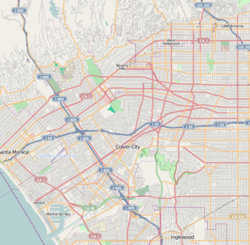

Venice boundaries | |

| Coordinates: 33°59′27″N 118°27′33″W / 33.99083°N 118.45917°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Los Angeles |

| City | Los Angeles |

| Founded as an independent city | 1905 |

| Merged with Los Angeles | 1926 |

| Named for | Venice, Italy |

| Government | |

| • City Council | Traci Park (D) |

| • State Senate | Ben Allen (D) |

| • State Assembly | Autumn Burke (D) |

| • U.S. House | Ted Lieu (D) |

| Area | |

• Total | 3.1 sq mi (8 km2) |

| Elevation | 10 ft (3 m) |

| Population (2008)[1] | |

• Total | 40,885 |

| • Density | 12,324/sq mi (4,758/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-8 (PST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-7 (PDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 90291, 90292 |

| Area codes | 310, 424 |

| Website | laparks |

Venice is a neighborhood of the City of Los Angeles within the Westside region of Los Angeles County, California, United States.

Venice was founded by Abbot Kinney in 1905 as a seaside resort town. It was an independent city until 1926, when it was annexed by Los Angeles. Venice is known for its canals, a beach, and Ocean Front Walk, a 2.5-mile (4 km) pedestrian promenade that features performers, fortune-tellers, and vendors.

History

[edit]19th century

[edit]In 1839, a region called La Ballona that included the southern parts of Venice, was granted by the Mexican government to Ygnacio and Augustin Machado and Felipe and Tomas Talamantes, giving them title to Rancho La Ballona.[3][4][5] Later this became part of Port Ballona.

Founding

[edit]

Venice, originally called "Venice of America", was founded by wealthy developer Abbot Kinney in 1905 as a beach resort town, 14 miles (23 km) west of Los Angeles. He and his partner Francis Ryan had bought 2 miles (3 km) of ocean-front property south of Santa Monica in 1891. They built a resort town on the north end of the property, called Ocean Park, which was soon annexed to Santa Monica. After Ryan died, Kinney and his new partners continued building south of Navy Street. After the partnership dissolved in 1904, Kinney, who had won the marshy land on the south end of the property in a coin flip with his former partners, began to build a seaside resort like the namesake Italian city.[6]: 8

When Venice of America opened on July 4, 1905, Kinney had dug several miles of canals to drain the marshes for his residential area, built a 1,200-foot-long (370 m) pier with an auditorium, ship restaurant, and dance hall, constructed a hot salt-water plunge, and built a block-long arcaded business street with Venetian architecture. Kinney hired artist Felix Peano to design the columns of the buildings.[6]: 22 Included in the capitals are several faces, modeled after Kinney and a woman named Nettie Bouck.[7][8]

Tourists, mostly arriving on the "Red Cars" of the Pacific Electric Railway from Los Angeles and Santa Monica, then rode the Venice Miniature Railway and gondolas to tour the town.[9] The biggest attraction was Venice's 1-mile-long (1.6 km) gently-sloping beach.[10] Cottages and housekeeping tents were available for rent.[11][12]

The population (3,119 residents in 1910) soon exceeded 10,000; the town drew 50,000 to 150,000 tourists on weekends.[13][citation needed]

Amusement pier

[edit]

For the amusement of the public, Kinney hired aviators to do aerial stunts over the beach. One of them, movie aviator and Venice airport owner B. H. DeLay, implemented the first lighted airport in the United States on DeLay Field (previously known as Ince Field). After a marine rescue attempt was thwarted, he organized the first aerial police force in the nation. DeLay performed many of the world's first aerial stunts for motion pictures in Venice.[citation needed]

Attractions on the Kinney Pier became more amusement-oriented by 1910, when a Venice Miniature Railway, Aquarium, Virginia Reel, Whip, Racing Derby, and other rides and game booths were added. Since the business district was allotted only three one-block-long streets, and the City Hall was more than a mile away, other competing business districts developed. Unfortunately, this created a fractious political climate. Kinney, however, governed with an iron hand and kept things in check. When he died in November 1920, Venice became harder to govern. With the amusement pier burning six weeks later in December 1920, and Prohibition (which had begun the previous January), the town's tax revenue was severely affected.[citation needed]

The Kinney family rebuilt their amusement pier quickly to compete with Ocean Park's Pickering Pleasure Pier and the new Sunset Pier. When it opened it had two roller coasters, a new Racing Derby, a Noah's Ark, a Mill Chutes, and many other rides. By 1925, with the addition of a third coaster, a tall Dragon Slide, Fun House, and Flying Circus aerial ride, it was the finest amusement pier on the West Coast. Several hundred thousand tourists visited on weekends. In 1923, Charles Lick built the Lick Pier at Navy Street in Venice, adjacent to the Ocean Park Pier at Pier Avenue in Ocean Park. Another pier was planned for Venice in 1925 at Leona Street (now Washington Street).

Politics

[edit]In 1922, Venice treasurer James T. Peasgood was convicted of embezzling thousands of dollars from the city government.[14] By 1925, Venice's politics had become unmanageable because its roads, water and sewage systems badly needed repair and expansion to keep up with its growing population. When it was proposed that Venice consolidate with Los Angeles, the board of trustees voted to hold an election. Consolidation was approved at the election in November 1925, and Venice was merged with Los Angeles in 1926.[6]: 8

Many streets were paved in 1929, following a three-year court battle led by canal residents. Afterward, the Department of Recreation and Parks intended to close three amusement piers, but had to wait until the first of the tidelands leases expired in 1946.[15]

Oil

[edit]In 1929, oil was discovered south of Washington Street on the Venice Peninsula, now known as the Marina Peninsula neighborhood of Los Angeles. Within two years, 450 oil wells covered the area, and drilling waste clogged the remaining waterways. The short-lived boom provided needed income to the community, which otherwise suffered during the Great Depression. Most of the wells had been capped by the 1970s, and the last wells, near the Venice Pavilion, were capped in 1991.[16]

Neglect

[edit]After annexation, the city of Los Angeles showed little interest in maintaining the unusual neighborhood. Most of the canals were filled in and paved over, and the former lagoon became a traffic circle. The neighborhood lacked the automobile-centric, homogeneous character that the city sought to cultivate in the post-World War II era, and was perceived as a dated, obsolete remnant of earlier decades' land speculation.[17]

Los Angeles had neglected Venice so long that, by the 1950s the neglect had led to the area being labeled the "Slum by the Sea". With the exception of new police and fire stations in 1930, the city spent little on improvements after annexation. The city did not pave Trolleyway (Pacific Avenue) until 1954 when county and state funds became available. Low rents for run-down bungalows attracted predominantly European immigrants (including a substantial number of Holocaust survivors) and young counterculture artists, poets, and writers. The Beat Generation hung out at the Gas House on Ocean Front Walk and at Venice West Cafe on Dudley.[18]

Past gang activity

[edit]The Venice Shoreline Crips and the Latino Venice 13 (V-13) were the two main gangs active in Venice. V13 dates back to the 1950s, while the Shoreline Crips were founded in the early 1970s, making them one of the first Crip sets in Los Angeles.[citation needed] In the early 1990s, V-13 and the Shoreline Crips were involved in a fierce battle over crack cocaine sales territories.[19]

By 2002, the numbers of gang members in Venice were reduced due to gentrification and increased police presence. According to a Los Angeles City Beat article, by 2003, many Los Angeles Westside gang members had resettled in the city of Inglewood.[20]

Housing and homelessness

[edit]Venice Beach is one of the most difficult places in the United States to build new housing due to stringent zoning regulations.[21] Between 2007 and 2022, the number of available housing units actually decreased, despite a massive increase in property values and construction activity over the same period.[21] The neighborhood was developed early in the history of Los Angeles, and as such much of the housing stock predates the current system of zoning regulations by decades. In the areas along Pacific avenue, many early 1900's multifamily buildings still exist, some housing as many as 30 units on a single lot with no parking. Current regulations mandate lower housing densities (most commonly 1 unit per 1,500 square feet of lot area).[22]

As per a 2020 count, there were around 2,000 homeless people in Venice,[23] up from 175 in 2014. Many of them take up residence in tents and tent cities.[24] An LAPD official said that the increased homeless population has contributed to a spike in crimes in Venice in 2021.[23] In February 2020, the city opened a 154-bed transitional housing shelter at a former Metro bus yard.[25]

Geography

[edit]

Venice is bounded on the northwest by the Santa Monica city line. The northern apex of the Venice neighborhood is at Walgrove Avenue and Rose Avenue, abutting the Santa Monica Airport. On the east, the boundary runs north–south on Walgrove Avenue to the neighborhood's eastern apex at Zanja Street, thus including the Penmar Golf Course but excluding Venice High School. The boundary runs on Lincoln Boulevard to Admiralty Way, excluding all of Marina del Rey, south to Ballona Creek.[26][27]

Cityscape

[edit]Venice Canal Historic District

[edit]

Abbot Kinney Boulevard

[edit]Abbott Kinney Boulevard is a principal attraction, with stores, restaurants, bars and art galleries lining the street. The street was described as "a derelict strip of rundown beach cottages and empty brick industrial buildings called West Washington Boulevard,"[28] and in the late 1980s community groups and property owners pushed for renaming a portion of the street to honor Abbot Kinney.[29][30] The renaming was widely considered as a marketing strategy to commercialize the area and bring new high-end businesses to the area.[31][32]

72 Market Street Oyster Bar and Grill

[edit]72 Market Street Oyster Bar and Grill was one of several historical footnotes associated with Market Street in Venice, one of the first streets designated for commerce when the city was founded in 1905. During the depression era, Upton Sinclair had an office there when he was running for governor, and the same historic building where the restaurant was located was also the site of the first Ace/Venice Gallery in the early 1970s.[33]

Historic post office

[edit]

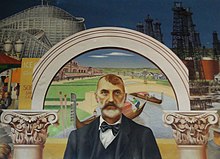

The Venice Post Office, a red-tile-roofed 1939 New Deal building designed by Louis A. Simon[34] on Windward Circle, featured one of two remaining murals painted in 1941 by Modernist artist Edward Biberman. Developer Abbot Kinney is in the center[35] surrounded by beachgoers in old-fashioned bathing suits, men in overalls, and a wooden roller coaster representing the Venice Pier on one side with contrasting industrial oil derricks that were once ubiquitous in the area on the other side.[36] Senior curator of American Art at Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), Ilene Susan Fort, said this is one of the better New Deal post office murals both artistically and historically. Although it contains brightly colored elements with amusing details, the intrusion of the ominous oil rigs and wells was very relevant at the time.[37]

After the post office closed in 2012, movie producer Joel Silver unveiled plans to purchase it for 7.5 million and revamp the building as the new headquarters of his company, Silver Pictures.[38] The sale included the stipulation that he, or any future owner, preserve the New Deal-era murals and allow public access.[39] Restoration of the nearly pristine mural took over a year and cost about $100,000. LACMA highlighted the mural with an exhibit that displayed additional Biberman artworks, rare historical documents and Venice ephemera with the restored mural. Silver has a long-term lease on the mural that is still owned by the US Postal Service.[37] In May 2019, according to the Hollywood Reporter, Silver sold the building for 22.5 million to U.K. investor Alex Dellal and his real estate group founded by Jack Dellal.[40] Status of the planned renovation remains subject to further approvals. The mural's whereabouts are unknown,[41] putting the lessee in violation of the lease agreement's public access requirement.[citation needed]

Residences and streets

[edit]Many of Venice's houses have their principal entries from pedestrian-only streets and have house numbers on these footpaths. (Automobile access is by alleys in the rear.) The inland walk streets are made up primarily of around 620 single-family homes.[42] Like much of the rest of Los Angeles, however, Venice is known for traffic congestion. It lies 2 miles (3.2 km) away from the nearest freeway, and its unusually dense network of narrow streets was not planned for modern traffic.

Venice Beach

[edit]

Venice Beach, which receives millions of visitors a year, has been labeled as "a cultural hub known for its eccentricities" as well as a "global tourist destination".[43][44] It includes the promenade that runs parallel to the beach, the Venice Beach Boardwalk, Muscle Beach, and the Venice Beach Recreation Center with handball courts, paddle tennis courts, a skate dancing plaza, and numerous beach volleyball courts. It also includes a bike trail and many businesses on Ocean Front Walk.[45]

The basketball courts in Venice are renowned across the country for their high level of streetball; numerous professional basketball players developed their games or have been recruited on these courts.[46]

Venice Beach will host surfing and 3x3 basketball during the 2028 Summer Olympics.[47]

Along the southern portion of the beach, at the end of Washington Boulevard, is the Venice Fishing Pier. A 1,310-foot (400 m) concrete structure, it first opened in 1964, was closed in 1983 due to El Niño storm damage, and re-opened in the mid-1990s. On December 21, 2005, the pier again suffered damage when waves from a large northern swell caused part of it to fall into the ocean.[48] The pier remained closed until May 25, 2006, when it was re-opened after an engineering study concluded that it was structurally sound.[citation needed]

The Venice Breakwater is an acclaimed local surf spot in Venice. It is located north of the Venice Pier and lifeguard headquarters and south of the Santa Monica Pier. This spot is sheltered on the north by an artificial barrier, the breakwater, consisting of an extending sand bar, piping, and large rocks at its end.[citation needed]

In late 2010, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors conducted a $1.6 million replacement of 30,000 cubic yards of sand at Venice Beach eroded by rainstorms in recent years. Although Venice Beach is located in the city of Los Angeles, the county is responsible for maintaining the beach under an agreement reached between the two governments in 1975.[49]

Oakwood

[edit]Oakwood lies inland from the tourist areas and is one of the few historically African-American areas in West Los Angeles.

East of Lincoln

[edit]East of Lincoln[50] is separated from Oakwood by Lincoln Boulevard. It extends east to the border with Mar Vista. Aside from the commercial strip on Lincoln (including the Venice Boys and Girls Club and the Venice United Methodist Church), the area almost entirely consists of small homes and apartments as well as Penmar Park and (bordering Santa Monica) Penmar Golf Course.

A housing project, Lincoln Place Apartment Homes, built by the Housing Authority of the City of Los Angeles, is currently undergoing a $140 million renovation to add 99 new market-rate apartment homes and to update the remaining 696 existing homes. A new pool, two-story fitness center, resident park and sustainable landscaping are being added.[51] Aimco, which acquired the property in 2003, had previously been in a legal battle to determine whether or not Lincoln Place could be demolished and rebuilt. In 2010, Aimco settled with tenants and agreed to reopen the project and return scores of evicted residents to their homes and add hundreds of units to the Venice area.[52]

Venice Walk Streets

[edit]The Venice Walk Streets are three pedestrian-only residential streets.

The streets are Marco Place, Amoroso Place and Nowita Place, located west of Lincoln Boulevard and east of Shell Avenue.

Los Angeles recognizes a larger North Venice Walk Streets Historic District.[53]

“The walk streets, narrower than regular streets, are too small for regulation street sweepers," so the streets had a designated smaller-size street sweeper.[54]

Subsections

[edit]According to the Venice Neighborhood Council,[55] the area can be subdivided further into the following districts:

- Ballona Lagoon West Bank

- Ballona Lagoon (Grand Canal) East Bank

- Silver Strand

- Marina Peninsula

- Venice Canals

- North Venice

- Oakwood-Milwood-South Venice

- Oxford Triangle

Climate

[edit]

Like much of the rest of coastal southern California, Venice has a warm-summer Mediterranean climate,[56] with mild, wet winters and warm, dry summers. Temperatures are moderate all year, and the neighborhood boasts over 300 sunshine days per year.[56] As a result of seasonal lag, fall is usually warmer than spring in Venice. Because of its coastal location, morning fog is a common phenomenon in May and June, but occasionally July and August, as well. Los Angeles residents have a particular terminology for this phenomenon: the "May Gray", the "June Gloom", "No-Sky July" and "Fogust"; during these events, the fog will usually burn off by noon, but the fog may also linger all day. The all-time record high of 110 °F (43 °C) was observed on September 27, 2010, while the all-time record low is 32 °F (0 °C), recorded on January 14, 2007.[57] Venice is in USDA plant hardiness zone 10b, closely bordering on 11a.[58]

| Climate data for Venice, Los Angeles | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 91 (33) |

90 (32) |

94 (34) |

100 (38) |

101 (38) |

103 (39) |

107 (42) |

103 (39) |

110 (43) |

101 (38) |

97 (36) |

86 (30) |

110 (43) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 64.6 (18.1) |

64.8 (18.2) |

65.2 (18.4) |

66.6 (19.2) |

68.2 (20.1) |

70.7 (21.5) |

74.2 (23.4) |

75.0 (23.9) |

74.4 (23.6) |

72.2 (22.3) |

68.4 (20.2) |

64.5 (18.1) |

69.1 (20.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 49.1 (9.5) |

49.5 (9.7) |

51.3 (10.7) |

53.2 (11.8) |

56.6 (13.7) |

59.9 (15.5) |

62.7 (17.1) |

63.0 (17.2) |

61.9 (16.6) |

58.2 (14.6) |

52.5 (11.4) |

48.4 (9.1) |

55.5 (13.1) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 32 (0) |

38 (3) |

39 (4) |

42 (6) |

48 (9) |

51 (11) |

56 (13) |

54 (12) |

51 (11) |

47 (8) |

38 (3) |

35 (2) |

32 (0) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.21 (82) |

3.47 (88) |

2.70 (69) |

0.59 (15) |

0.27 (6.9) |

0.04 (1.0) |

0.02 (0.51) |

0.13 (3.3) |

0.16 (4.1) |

0.36 (9.1) |

1.04 (26) |

1.89 (48) |

13.89 (353) |

| Source: [58][59][60] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]This section needs to be updated. (January 2020) |

The 2000 U.S. census counted 37,705 residents in the 3.17-square-mile Venice neighborhood—an average of 11,891 people per square mile, about the norm for Los Angeles; in 2008, the city estimated that the population had increased to 40,885. The median age for residents was 35, considered the average for Los Angeles; the percentages of residents aged 19 through 49 were among the county's highest.[26]

The ethnic breakdown was 64.2% Non-Hispanic White, 21.7% Latino (of any racial origin); 5.4% African American; 4.1% Asian, and 4.6% of other origins. About 22.3% of residents had been born abroad, a relatively low figure for Los Angeles; Mexico (38.4%) and the United Kingdom (8.5%) were their most common places of birth.[26]

Forty-nine percent of Venice residents aged 25 and older had earned a four-year degree by 2000, a high figure for both the city and the county. The percentages of residents of that age with a bachelor's degree or a master's degree was considered high for the county.[26]

The median yearly household income in 2008 dollars was $67,647, a high figure for Los Angeles. The percentage of households earning $125,000 was considered high for the city. The average household size of 1.9 people was low for both the city and the county. Renters occupied 68.8% of the housing stock and house- or apartment owners held 31.2%.[26] Property values have been increasing lately due to the presence of technology companies such as Google Inc. (which in 2011 began leasing 100,000 square feet of space in Venice) and Snap Inc. (which formerly leased property on Market Street and Abbot Kinney).[61]

The percentages of never-married men (51.3%), never-married women (40.6%), divorced men (11.3%) and divorced women (15.9%) were among the county's highest. The percentage of veterans who had served during the Vietnam War was among the county's highest.[26]

Arts and culture

[edit]

Venice has been known as a preferred location for creative artists.[62] In the 1950s and 1960s, Venice became a center for the Beat generation and there was an explosion of poetry and art, which continues today.[63] Major writers and artists throughout the decades have included Stuart Perkoff, John Thomas, Frank T. Rios, Tony Scibella, Lawrence Lipton, John Haag, Saul White, Millicent Borges Accardi Robert Farrington, Philomene Long, and Tom Sewell.[18]

Architecture

[edit]Originally established as a planned city imitating Venice, Italy, Venice is home to a large number of early 1900s buildings built to emulate Italian Renaissance architecture. Particularly along Windward Avenue, where an arched arcade covers the sidewalks on portions of both sides of the street. Similar buildings originally formed a continuous arcade from the boardwalk to the former lagoon (now the Windward traffic circle) but these were condemned by the City of Los Angeles after annexation. Only through the efforts of local preservationists were the few buildings that remain able to be preserved, although many were substantially modified.

Designers Charles and Ray Eames had their offices at the Bay Cities Garage on Abbot Kinney Boulevard from 1943 on, when it was still part of Washington Boulevard; Eames products were also manufactured there until the 1950s.[65] The brick building's interior was redesigned by Frank Israel in 1990 as a creative workspace, opening up the interior and creating sightlines all the way through the building.[66]

Originally located at the Venice home of Pritzker Prize–winning architect and SCI-Arc founder Thom Mayne, the Architecture Gallery was in existence for just ten weeks in 1979 and featured new work by then-emerging architects Frank Gehry, Eric Owen Moss, and Morphosis.[67] Constructed on a long, narrow lot in 1981, the Indiana Avenue Houses/Arnoldi Triplex was designed Frank Gehry in partnership with artists Laddie John Dill and Charles Arnoldi.[66] Frank Gehry has designed several well-known houses in Venice, including the Jane Spiller House (completed 1979) and the Norton House (completed 1984) on Venice Beach.[68] In 1994, sculptor Robert Graham designed a fortress-like art studio and residence for himself and his wife, actress Anjelica Huston, on Windward Avenue.[69]

Art

[edit]In the 1970s, performance artist Chris Burden created some of his early, groundbreaking work in Venice. Other notable artists who maintained studios in the area include Charles Arnoldi, Jean-Michel Basquiat,[70] John Baldessari, Larry Bell, Billy Al Bengston, James Georgopoulos, Dennis Hopper, and Ed Ruscha.[71] Organized by the Hammer Museum over the course of one weekend in 2012,[72] the open-air Venice Beach Biennial (in reference to the Venice Biennale in Italy) brought together 87 artists, including site-specific projects by established artists like Evan Holloway, Barbara Kruger as well as boardwalk veteran Arthure Moore.[73] In the 1980s and 1990s, the Venice Beach boardwalk became a mecca for street performances, turning it into a popular tourist attraction. Chainsaw jugglers, break dancers, acrobats and comics like Michael Colyar could be seen on a daily basis. Many performers like the Jim Rose Circus got their start on the boardwalk.[citation needed]

Venice Boardwalk murals

[edit]Venice Beach boardwalk murals include:

- Venice Kinesis (2010) by Rip Cronk [a revision of earlier Venice Reconstituted (1989)]

- Homage to a Starry Knight (1990) by Rip Cronk

- Endangered Species (1990) by Emily Winters

- Venice Beach (1990) by Rip Cronk

- Morning Shot (1991) by Rip Cronk (portrait mural of musician Jim Morrison)

- Touch of Venice (2012) by Jonas aka "Never"

- Arnold Schwarzenegger (2013) by Jonas aka "Never" (portrait mural of Schwarzenegger in bodybuilding pose.[74]

- Luminaries of Pantheism (2015) by Levi Ponce (depicts pantheism supporters, including Einstein, Tesla, Du Bois, and others)

Venice Public Art Walls

[edit]The Venice Art Walls were built in 1961 as part of the Venice Pavilion, a recreation and performing arts facility.[75] It was a popular hangout spot for locals owing to its proximity to the beach and large number of concrete tables. The central area of the pavilion, known as "the pit" was surrounded by flat concrete walls that made for ideal painting surfaces. The pit became a hotbed of the growing graffiti movement in Los Angeles in the 1970s and 1980s, with many prominent artists and graffiti crews painting elaborate pieces on the pavilions walls. The area's thriving counterculture and arts scene, along with law enforcement's general neglect of the area made it an ideal location for artists to paint.[76][77] Thirty-eight years later the Venice Pavilion was torn down but some of the walls, along with two large, conical concrete structures, were maintained. They were restored in 2000 as part of a renovation of the beachfront park area at the end of Windward Avenue, and ever since artists have been allowed to paint there freely and legally.

Music

[edit]Venice was where rock band The Doors were formed in 1965 by UCLA alumni Ray Manzarek and Jim Morrison. The Doors would go on to be inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame with Morrison being considered one of the greatest rock frontmen. Venice is the birthplace of Jane's Addiction in the 1980s. Perry Farrell, frontman and founder of Lollapalooza, was a longtime Venice resident until 2010.[78][79]

Venice in the 1980s also had bands playing music known as crossover thrash, a hardcore punk/thrash metal musical hybrid. The most notable of these bands is Suicidal Tendencies. Other Venice bands such as Beowülf, No Mercy, and Excel were also featured on the compilation album Welcome to Venice.[citation needed]

Public libraries

[edit]The Los Angeles Public Library operates the Venice–Abbot Kinney Memorial Branch.[80]

Street performers and eclectic characters

[edit]Venice is well known for its street performers, or buskers. The most famous is Harry Perry, a turbaned, roller skating guitar player.[81][82] Other well-known Venice street performers include the Venice Beach Glass Man,[83] Echoman, Dr. Geek, Sid Weiss,[84] and the Chain Saw Juggler.[85]

Though not a street performer, "Boston Dawna" Chaet was a notable Venice character in the 1990s who cut hair by day, and patrolled the streets by night on. her bicycle, assisting the local police and making numerous citizens' arrests to keep the neighborhood safe.[86]

Parks and recreation

[edit]

The Venice Beach Recreation Center comprises a number of facilities.[87] The installation has basketball courts (unlighted/outdoor), several children play areas with a gymnastics apparatus, chess tables, handball courts (unlighted), paddle tennis courts (unlighted), and volleyball courts (unlighted). At the south end of the area is the muscle beach outdoor gymnasium. In March 2009, the city opened a sophisticated $2 million skate park, the Venice Beach Skate Park, on the sand towards the north.[88] The Graffiti Walls are on the beach side of the bike path in the same vicinity.

The Oakwood Recreation Center, which also acts as a Los Angeles Police Department stop-in center, includes an auditorium, an unlighted baseball diamond, lighted indoor basketball courts, unlighted outdoor basketball courts, a children's play area, a community room, a lighted American football field, an indoor gymnasium without weights, picnic tables, and an unlighted soccer field.[89]

The Westminster Off-Leash Dog Park is located in Venice.[90]

Government

[edit]

Venice is a neighborhood in the city of Los Angeles represented by District 11 on the Los Angeles City Council. City services are provided by the city of Los Angeles. There is a Venice Neighborhood Council that advises the LA City Council on local issues.

County, state, and federal representation

[edit]The Los Angeles County Department of Health Services SPA 5 West Area Health Office serves Venice.[91]

The United States Postal Service operates the Venice Post Office at 1601 Main Street and the Venice Carrier Annex at 313 Grand Boulevard.[92][93]

Education

[edit]

Schools within Venice include:[94]

- Broadway Elementary School

- Animo Venice Charter High School

- Venice Skills Center

- Westminster Avenue Elementary School

- Coeur d'Alene Avenue Elementary School

- St. Mark's Catholic School

- Westside Leadership Magnet School

- Venice High School[95][96]

Infrastructure

[edit]Fire department

[edit]The Los Angeles Fire Department operates Station 63, which serves Venice with two engines, a truck, and an ALS rescue ambulance.

Police

[edit]The Los Angeles Police Department serves the area through the Pacific Community Police Station as well as a beach sub-station.[97]

Lifeguards

[edit]Lifeguard protection is administered by the Los Angeles County Lifeguards of the Los Angeles County Fire Department.

Notable people

[edit]- Fiona Apple, singer-songwriter, pianist.[98]

- Margot Robbie, actress and producer

- Jay Adams, professional skateboarder

- J.C. Barthel, Venice postmaster and commissioner of supplies, 1920s, president of Chamber of Commerce[99]

- Charles Benefiel, artist

- Millicent Borges Accardi, poet and writer, National Endowment for the Arts fellow and long-time Venice resident

- Charles Winchester Breedlove, Los Angeles City Council member, 1933–45, supported legalized tango games[100]

- Bryan Callen, stand-up comedian, actor, writer and podcaster

- Brun Campbell, folk ragtime musician

- Emilia Clarke, actress

- John J. Coit, builder and operator of Venice Miniature Railway

- Zack de la Rocha, musician

- John Doan, classical guitarist

- Tom Felton, actor, musician

- Sky Ferreira, singer-songwriter, model, actress

- C.H. Garrigues, journalist, Venice Vanguard

- Lennon Sisters, singers

- John Lovell, businessman, member of Los Angeles Common Council[101]

- John Lydon, "Johnny Rotten", lead singer of the Sex Pistols and Public Image Ltd

- Helene Machado, All-American Girls Professional Baseball League player, born and raised in Venice

- Milo Manheim, actor who stars as Zed in the Disney Channel Original Movies, Zombies and Zombies 2

- Ian McShane, actor[102]

- Betty Miller, first female pilot to fly solo across the Pacific Ocean, born and raised in Venice

- Berniece Baker Miracle, author and half-sister of Marilyn Monroe

- Casey Neistat, filmmaker, vlogger, YouTuber

- Lou Niles, radio host of 91X and executive director of Oceanside International Film Festival

- Anna Paquin, actress[103]

- James Edwin Richards, crime activist and citizen journalist, editor and publisher[104]

- Ronda Rousey, mixed martial artist, judoka, actress, and professional wrestler[105]

- Karl L. Rundberg, Los Angeles City Council member (1957–65), opposed Venice beatniks[106]

- Lila Shanley, stage name Lila Finn, stuntwoman, stunt double, and women's volleyball player

- Joanie Sommers, singer[107]

- Teena Marie, singer-songwriter, producer[108]

In popular culture

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2024) |

Venice has been the location of numerous movies, TV shows, and video games.[109] Common locations for filming include the piers, skate park, restaurant, canals, boardwalk, and the schools.

Some productions include the following:

- 1914: Kid Auto Races at Venice (Charlie Chaplin — first appearance of the "Little Tramp" character)

- 1920: Number, Please? (Harold Lloyd)

- 1921: The High Sign (Buster Keaton)

- 1923: The Balloonatic (Buster Keaton)

- 1927: Sugar Daddies (Laurel and Hardy)

- 1928: The Circus (Charlie Chaplin)

- 1928: The Cameraman (Buster Keaton)

- 1958: Touch of Evil (Orson Welles) – shot entirely in Venice except for one indoor scene, selected by Welles as a stand-in for a fictional run-down Mexican border town.

- 1961: Night Tide (Dennis Hopper, Linda Lawson, written and directed by Curtis Harrington)—Shot entirely in Venice and shows the deteriorated nature of the area in the 1950s.

- 1972: One Pair of Eyes – Reyner Banham loved Los Angeles – architectural critic Reyner Banham explores Los Angeles in 1972.[110]

- 1976: The Witch Who Came from the Sea (Millie Perkins, directed by Matt Cimber)

- 1979: CHiPs Roller Disco (Episodes 1 and 2 of season 3. Directed by Ron Weiss. Aired September 22, 1979)

- 1979: Roller Boogie (Linda Blair, directed by Mark L. Lester)

- 1979: Incredible Hulk (Bill Bixby) "No Escape"

- 1988: Colors

- 1991: The Doors (Val Kilmer, directed by Oliver Stone)

- 1992: White Men Can't Jump

- 1993: Falling Down

- 1994: Speed (Keanu Reeves)

- 1997: Romy and Michele's High School Reunion

- 1998: The Big Lebowski

- 1998: Jeans (1998 Tamil film)

- 1998: American History X

- 2001: Dogtown and Z-Boys

- 2003: Thirteen (Holly Hunter)

- 2004: Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas as Verona Beach

- 2005: Lords of Dogtown

- 2006: Tenacious D in The Pick of Destiny

- 2007: Californication

- 2010: Billionaire (Travie McCoy)[111]

- 2011: Wilfred

- 2012: Amazing Race[112]

- 2013: Grand Theft Auto V as Vespucci Beach

- 2013: Sugar

- 2013–2014: Sam & Cat

- 2009–2015: American Ninja Warrior

- 2014: Alex of Venice

- 2015: Kidz Bop 29 (music video shot in Venice Beach, California)

- 2015: Roho Ololo as Ro7o Ololo (Sandy)

- 2015: The Amazing Race 27[113]

- 2016: Flaked

- 2017: Once Upon a Time in Venice

- 2017: Ingrid Goes West

- 2018: Humility

- 2018: Yalla Habibi (Ragheb Alama featuring Seyi Shay and Costi) (music video shot in Romania)

- 2020: Scoob![114]

- 2023: Dead Island 2

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "Los Angeles Times Neighborhood Project". Archived from the original on June 19, 2013. Retrieved April 11, 2010.

- ^ "Worldwide Elevation Finder".

- ^ "Diseños : maps and plans of ranchos of Southern California, mostly within Los Angeles and Orange counties". oac.cdlib.org.

- ^ "Redondo". USGS Historical Topographic Map Explorer. 1896.

- ^ "Map of old Spanish and Mexican ranchos in Los Angeles County". Archived from the original on July 27, 2016. Retrieved June 29, 2014.

- ^ a b c Elayne Alexander; Bryan L. Mercer (February 2, 2009). Venice. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-6966-6. Retrieved January 9, 2013.

- ^ "Peano's Faces of Venice Beach – Los Angeles, California". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved April 17, 2018.

- ^ "Betsy Sells Venice". Venice Vanguard Newsletter. September 2005. Archived from the original on April 18, 2018. Retrieved April 17, 2018 – via Betsysellsvenice.com.

These cast iron sculptures were done by Felix Peano, an Italian sculptor whose work achieved more than a modest degree of fame at the turn of the century. Peano was an intimate friend of Jack London and was well known in the San Francisco Bay area. He was employed by Abbot Kinney to add his embelishments to the dream called Venice of America. The faces on the columns are classical in style, easily traceable to the influence of ancient Rome. Yet Peano did not go all the way back in time for his inspiration. He found it in a young girl of 17 who was living on the ocean front in 1904, watching Venice grow around her. "It was almost an embarrassing moment," explains Nettie Bouck. "Felix Peano was at our house, actually at that time it was the house of my future father-in-law, Mr. Bouck. I don´t know why. He just all of a sudden reached out and grabbed me. He was an Italian gentleman and very, very emotional. And he held my face, my hands, put his hands on my face and looked at it." Peano insisted that he would use those features in the work he was doing for Mr. Kinney. They showed up as the female face atop the Windward Avenue pillars. "Well, it was not a likeness of me, but the face, the contours of my face, gave him the idea to use it for the heads on the columns. There was really no big story or history about it," insists Mrs. Bouck, "except that he got a little bit over-enthusiastic I guess."

- ^ Crump, S. (1962). Ride the Big Red Cars: How Trolleys Helped Build Southern California. Gerald E. Brookins Collection. Crest Publications. Retrieved April 24, 2023.

- ^ Alexander, E.; Mercer, B.L. (2009). Venice. Postcard History Series. Arcadia Pub. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-7385-6966-6. Retrieved April 24, 2023.

- ^ "Canal scene at Venice of America". Jstor. Retrieved April 24, 2023.

- ^ Alexander, E.; Mercer, B.L. (2009). Venice. Postcard History Series. Arcadia Pub. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-7385-6966-6. Retrieved April 24, 2023.

- ^ Rogers, Sam; Steuart, W.M (1921). "State Compendium California" (PDF). Department of Commerce. 14: 196.

- ^ "Venice Treasurer Gets Prison Term". The San Francisco Examiner. December 12, 1922. p. 9. Retrieved June 1, 2024.

- ^ Stanton, Jeffrey. "Debunking Venice's Historic Myths". VENICE HISTORY SITE. Retrieved April 22, 2019.

- ^ Doherty, Shawn (October 29, 1991). "With Oil Wells Capped, Venice Beach Looks to Cleanup". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 22, 2019.

- ^ "FHA Area Description of South Venice". Mapping Inequality. March 3, 1939.

- ^ a b Maynard, John Arthur (1993). Venice West: The Beat Generation in Southern California. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-1965-4.

- ^ Davidson, Ronald A.; Entrikin, J. Nicholas (October 2005). "The Los Angeles Coast as a Public Place". Geographical Review. 95 (4): 578–593. Bibcode:2005GeoRv..95..578D. doi:10.1111/j.1931-0846.2005.tb00382.x. hdl:10211.2/1731. JSTOR 30034261. S2CID 159996450.

- ^ Romero, Dennis (November 6, 2003). "Gangster's Paradise Lost". Los Angeles City Beat. Archived from the original on December 24, 2007. Retrieved February 15, 2008.

- ^ a b Kusisto, Laura (July 16, 2017). "Venice Beach Is a Hot Place to Live, So Why Is Its Housing Supply Shrinking?". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved August 29, 2022.

- ^ "Department of City Planning - Generalized summary of zoning regulations" (PDF). planning.lacity.org.

- ^ a b "Venice described as 'constant emergency zone' as calls grow for action to address homelessness crisis". KTLA. May 25, 2021. Retrieved June 8, 2021.

- ^ Johnson, Scott; Kiefer, Peter (January 11, 2019). "LA's Battle for Venice Beach: Homeless Surge Puts Hollywood's Progressive Ideals to the Test". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved May 15, 2021.

- ^ Cheney, Alex (February 26, 2020). "Venice temporary homeless shelter opens with 154 beds, some dedicated to youth living on streets". ABC7 Los Angeles. Retrieved June 8, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f "Venice", Mapping L.A., Los Angeles Times

- ^ The Thomas Guide: Los Angeles County, 2004, pages 671, 672 and 702

- ^ Janelle Brown (November 20, 2005), Venice, Calif., Is Turning Into Sunrise Boulevard The New York Times

- ^ Nancy Hill-Holtzman (August 10, 1989), Plan for Kinney Boulevard in Venice Runs Into Pothole Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Nancy Hill-Holtzman (February 25, 1990), Part of Washington Blvd. to Be Renamed Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Departures: Venice – Chapter 5: Abbot Kinney Boulevard Archived March 3, 2013, at the Wayback Machine KCET.

- ^ Groves, Martha (October 25, 2013) "Abbot Kinney Boulevard's renaissance a mixed blessing" Los Angeles Times

- ^ McKenna, Kristine (October 9, 2003). "The Ace is Wild: The Doug Chrismas Story". LA Weekly. Archived from the original on October 26, 2012. Retrieved January 26, 2012.

- ^ Venice Post Office Los Angeles Conservancy Retrieved April 24, 2014

- ^ Tobar, Hector (November 11, 2011), There's a special stamp on the Venice post office Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Groves, Martha (January 7, 2010), Producer Joel Silver buys former U.S. post office in Venice Los Angeles Times.

- ^ a b Vankin, Deborah, (June 17, 2014) "Restored 'Abbot Kinney' mural anchors exhibit on Venice history" Los Angeles Times; accessed February 7, 2022.

- ^ Groves, Martha (October 11, 2012), Joel Silver to put his stamp on Venice Post Office Los Angeles Times

- ^ Hiatt, Anna (January 20, 2014) "Congress wants delay in selling of historic post offices until federal report is completed" The Washington Post

- ^ "L.A.'s Iconic Venice Post Office Falls Into Limbo Again After Joel Silver Sale". The Hollywood Reporter. July 23, 2019.

- ^ freevenicebeachhead (June 12, 2016). "Judge Garland Stumbles Over The Venice Post Office". Free Venice Beachhead. Archived from the original on June 13, 2016. Retrieved June 18, 2016.

- ^ Leah Ziskin (August 12, 2007), It's purely pedestrian Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "Venice boardwalk crash: Victims describe moments of horror". Los Angeles Times. August 5, 2013.

- ^ "L.A. City Council calls for boardwalk barriers in Venice". Los Angeles Times. August 6, 2013.

- ^ venice1. "The Venice Beach Boardwalk". Venice Beach. Archived from the original on March 21, 2019. Retrieved March 18, 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Court profile of Venice Beach basketball court". courtsoftheworld.com.

- ^ "Stage 2 Governance, legal and venue funding" (PDF).

- ^ "Venice Pier's Future Still Awash in Doubt". Los Angeles Times. February 16, 2006. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved April 4, 2019.

- ^ Rong-Gong Lin II (October 12, 2010), $1.6-million county project approved to replace sand on Venice Beach Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "Venice Neighborhoods". Venice Neighborhood Council. Retrieved January 9, 2021.

- ^ [1] multifamilybiz.com

- ^ Groves, Martha (May 26, 2010). "Los Angeles, developer reach deal to preserve Venice's landmark Lincoln Place apartments". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 14, 2014.

- ^ "Report – HPLA". historicplacesla.org. Retrieved June 25, 2022.

- ^ "Sweeper Rolls Again on Venice Streets", Los Angeles Times, December 3, 1989.

- ^ "Venice Neighborhood Council MAP".

- ^ a b "Venice Beach climate info | what's the weather like in Venice Beach, California (U.S.A.)". www.whatstheweatherlike.org.

- ^ "Los Angeles, CA Weather History | Weather Underground". www.wunderground.com.

- ^ a b "Zipcode 90291 – Venice, California Hardiness Zones".

- ^ "Records and Averages for Venice, California". www.msn.com. Retrieved April 7, 2021.

- ^ "Climate in Zip 90291 (Los Angeles, CA)". www.bestplaces.net. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ^ Donna Kardos Yesalavich (April 1, 2014), Cut! Actress Anjelica Huston Finds a Buyer The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ Dave, Paresh (March 31, 2015). "Is Snapchat's rapid growth changing Venice's funky vibe?". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "Venice Poets". Archived from the original on September 1, 2004.

- ^ "Binoculars". Los Angeles Historic Resources Inventory. 2017. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- ^ Roger Vincent (July 15, 2012), Former Eames furniture design headquarters sold in Venice Los Angeles Times.

- ^ a b Eve Bachrach (May 3, 2013), Touring 3 of Venice's Modern Arch Gems of the '70s and '80s Curbed LA.

- ^ A Confederacy of Heretics: The Architecture Gallery, Venice, 1979; Southern California Institute of Architecture, Los Angeles; March 29 – July 7, 2013 Graham Foundation, Chicago.

- ^ Mildred Friedman (2009) "Frank Gehry The Houses", Rozzoli, New York

- ^ Lauren Beale (March 7, 2012), Venice live/work space of Anjelica Huston, Robert Graham for sale Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Fred Hoffman (March 13, 2005), Basquiat's L.A. Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Edward Wyatt (August 11, 2008), Economic Realities Press on Artists’ Outdoor Eden The New York Times.

- ^ The Venice Beach Biennial Archived September 25, 2012, at the Wayback Machine Hammer Museum, Los Angeles.

- ^ Jori Finkel (July 11, 2012), Venice Beach gets a breezy Biennial on the boardwalk Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "" Schwarzenegger Meets Muralist Jonas AKA "Never" "". October 2, 2013. Retrieved November 4, 2020.

- ^ "World Famous Venice Graffiti Art Walls". Venice Art Walls. Retrieved November 5, 2020.

- ^ "Visit or paint at the Venice Art Walls. Also known as the Venice Graffiti Walls. – Venice Paparazzi | Venice Beach CA, Photo Agency, Community Info, News, Events". Retrieved October 5, 2019.

- ^ "Looking Back At Where the 'Debris Meets The Sea' – THE VENICE PAVILION WAS THE 80's/90's MELTING POT OF SKATE/SURF/ART CULTURE". What Youth. May 10, 2018. Retrieved October 5, 2019.

- ^ "Venice native, Perry Farrel & Jane's Addiction are back | FREE Download off their new album due out in August". WE LOVENICE. Archived from the original on March 13, 2014. Retrieved March 12, 2014.

- ^ "Alt-rocker Perry Farrell breaks his Venice addiction". Los Angeles Times. May 26, 2010. Retrieved March 12, 2014.

- ^ "Venice – Abbot Kinney Memorial Branch." Los Angeles Public Library. Retrieved March 18, 2010.

- ^ McPhee, Michele (April 3, 2024). "Meet the Legendary Rock and Roller Who Saved Venice Beach's Artist Community". www.lamag.com. Los Angeles Magazine. Retrieved June 18, 2024.

- ^ Kreuzer, Nikki (May 8, 2014). "Offbeat L.A.: Harry Perry - The Guitar Playing, Rollerskating, Turban Wearing Kosmic Krusader of Venice Beach". thelosangelesbeat.com. The Los Angeles Beat. Retrieved June 18, 2024.

- ^ Cross, Justin. "7 amazing street performers you'll see on the Venice Beach Boardwalk". www.timeout.com. TimeOut. Retrieved June 18, 2024.

- ^ Schuster, Clark (April 3, 1997). "Venice Bops to Beat of Local Musical Giants The J-Gos". Venice Vanguard. Retrieved June 18, 2024.

- ^ "Street Performers". www.westland.net. Westland. Retrieved June 18, 2024.

- ^ "Boston Dawna, the Batman of Venice Beach, retires". The San Diego Union-Tribune. September 7, 2010. Retrieved June 18, 2024.

- ^ "Venice Beach Recreation Center." City of Los Angeles. Retrieved March 22, 2010.

- ^ "VENICE BEACH SKATE PARK | City of Los Angeles Department of Recreation and Parks". City of Los Angeles Department of Recreation and Parks. August 4, 2014. Retrieved February 6, 2022.

- ^ "[2] Archived July 12, 2016, at the Wayback Machine." City of Los Angeles. Retrieved January 22, 2011.

- ^ Home page Archived November 27, 2020, at the Wayback Machine." Westminster Off-Leash Dog Park. Retrieved March 22, 2010.

- ^ "About Us." Los Angeles County Department of Health Services. Retrieved March 18, 2010.

- ^ "Post Office Location – VENICE Archived February 10, 2009, at the Wayback Machine." United States Postal Service. Retrieved December 6, 2008.

- ^ "Post Office Location – VENICE CARRIER ANNEX Archived February 10, 2009, at the Wayback Machine." United States Postal Service. Retrieved December 6, 2008.

- ^ [3] "Venice Schools", Mapping L.A., Los Angeles Times

- ^ "Venice Plan Map" (PDF). Retrieved August 4, 2022.

Venice High is indicated in dark green on map with the notation SH (senior high)

- ^ "Venice: Community Plan" (PDF). p. 69. Retrieved August 4, 2022.

- ^ Pacific Community Police Station – official website of THE LOS ANGELES POLICE DEPARTMENT. Lapdonline.org.

- ^ Nussbaum, Emily (March 16, 2020). "Fiona Apple's Art of Radical Sensitivity". The New Yorker. Retrieved September 6, 2022.

These days, the singer-songwriter, who is forty-two, rarely leaves her tranquil house, in Venice Beach, other than to take early-morning walks on the beach with Mercy.

- ^ "Preview unavailable - ProQuest". www.proquest.com. ProQuest 161172090.

- ^ "Preview unavailable - ProQuest". www.proquest.com. ProQuest 163119377.

- ^ "Preview unavailable - ProQuest". www.proquest.com. ProQuest 159985189.

- ^ Gilbey, Ryan (March 16, 2013). "Ian McShane: rogue trader". The Guardian. Retrieved March 18, 2013.

- ^ "Anna Paquin and Stephen Moyer Get Married!". Us Weekly. August 21, 2010.

- ^ "Was an LA Activist Shot for His Anti-Crime Efforts?". ABC News.

- ^ VenicePaparazzi (February 23, 2013) "Venice resident Ronda Rousey wins with an arm bar submission at UFC 157!"

- ^ Smith, Jack (June 24, 1965). "Bohemians Make City Hall Scene, But Lose Battle of Bongos". Los Angeles Times. p. 1. ProQuest 155207409.

- ^ "Joanie Sommers Biography, Songs, & Albums". AllMusic. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ "Teena Marie". Los Angeles Times. March 13, 2014. Retrieved September 13, 2020.

- ^ Venice – Movie Making and TV shows at Venice Beach. Westland.net (November 11, 2006).

- ^ "Reyner Banham Loves Los Angeles (1972) on Vimeo".

- ^ Fueled By Ramen (May 3, 2010), Travie McCoy: Billionaire (Beyond The Video), archived from the original on November 7, 2021, retrieved March 8, 2019

- ^ "Amazing Race: Ouceni et Lassana éliminés, Marilyn Monroe ressuscitée?" [Amazing Race: Ouceni and Lassana eliminated, Marilyn Monroe resurrected?]. Purepeople (in French). November 20, 2012. Retrieved January 19, 2020.

- ^ "'Amazing Race' Kicks Off 27th Season At Venice Beach". KCBS-TV. June 22, 2015. Retrieved January 19, 2020.

- ^ Burwick, Kevin (May 15, 2020). "Watch the First 5 Minutes of Scoob!, Streaming on PVOD This Weekend". MovieWeb. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

Further reading

[edit]- Deener, Andrew (2012). Venice: A Contested Bohemia in Los Angeles. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-14000-1. Retrieved January 9, 2013.

- Maynard, John Arthur (1993). Venice West: The Beat Generation in Southern California. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-1965-4.

- Schmidt-Brümmer, Horst (1973). Venice, California: An Urban Fantasy. Grossman Publishers. ISBN 978-0-670-74506-7. Street art pictorial works.

- Stanton, Jeffrey (2005). Venice, California: Coney Island of the Pacific. Donahue Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9619849-3-9. History of Venice with 367 historic photographs.

External links

[edit]- Venice, Los Angeles

- 1905 establishments in California

- Beaches of Los Angeles County, California

- Beaches of Southern California

- Busking venues

- Former municipalities in California

- Landmarks in Los Angeles

- Neighborhoods in Los Angeles

- Olympic surfing venues

- Olympic basketball venues

- Olympic skateboarding venues

- Venues of the 2028 Summer Olympics

- Parks in Los Angeles

- Populated coastal places in California

- Seaside resorts in California

- Westside (Los Angeles County)