Santiago de Compostela

Santiago de Compostela | |

|---|---|

|

| |

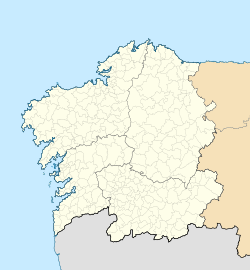

Location of Santiago de Compostela | |

| Coordinates: 42°52′40″N 8°32′40″W / 42.87778°N 8.54444°W | |

| Country | Spain |

| Autonomous Community | Galicia |

| Province | A Coruña |

| Parishes | 30

|

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor–council |

| • Body | Council of Santiago |

| • Mayor | Goretti Sanmartín (BNG) |

| Area | |

| 220 km2 (80 sq mi) | |

| Elevation | 260 m (850 ft) |

| Population (2020)[1] | |

| 97,849 | |

| • Density | 440/km2 (1,200/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 183,855 |

| Demonyms | |

| Time zone | CET (GMT +1) |

| • Summer (DST) | CEST (GMT +2) |

| Area code | +34 |

| Website | santiagodecompostela |

Santiago de Compostela,[a] simply Santiago, or Compostela,[3] in the province of A Coruña, is the capital of the autonomous community of Galicia, in northwestern Spain. The city has its origin in the shrine of Saint James the Great, now the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela, as the destination of the Way of St. James, a leading Catholic pilgrimage route since the 9th century.[4] In 1985, the city's Old Town was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Santiago de Compostela has a very mild climate for its latitude with heavy winter rainfall courtesy of its relative proximity to the prevailing winds from Atlantic low-pressure systems.

Toponym

[edit]According to Richard Fletcher scholars now agree that the origin of the name Compostela comes from the Latin compositum tella, meaning a well-ordered burial ground, possibly referring to an ancient burial ground on the site of the Church of Santiago de Compostela that pre-dates the Christian building.[5]

Santiago is the local Galician evolution of Vulgar Latin Sanctus Iacobus "Saint James". According to folk etymology Compostela derives from the Latin: Campus Stellae ('field of the star').

City

[edit]According to a medieval legend, the remains of the apostle James, son of Zebedee were brought to Galicia for burial, where they were lost. Eight hundred years later the light of a bright star guided a shepherd, Pelagius the Hermit, who was watching his flock at night to the burial site in Santiago de Compostela.[6] This site was originally called Mount Libredon and its physical topography leads prevalent seaborne winds to clear the cloud deck immediately overhead.[7] The shepherd quickly reported his discovery to the bishop of Iria, Theodemir.[6] The bishop declared that the remains were those of the apostle James and immediately notified King Alfonso II in Oviedo.[6] To honour St. James, the cathedral was built on the spot where his remains were said to have been found. The legend, which included numerous miraculous events, enabled the Catholic faithful to bolster support for their stronghold in northern Spain during the Christian crusades against the Moors, but also led to the growth and development of the city.[6]

Along the western side of the Praza do Obradoiro is the elegant 18th-century Pazo de Raxoi, now the city hall. Across the square is the Pazo de Raxoi (Raxoi's Palace), the town hall, and on the right from the cathedral steps is the Hostal dos Reis Católicos, founded in 1492 by the Catholic Monarchs, Isabella of Castille and Ferdinand II of Aragon, as a pilgrims' hospice (now a Parador). The Obradoiro façade of the cathedral, the best known, is depicted on the Spanish euro coins of 1 cent, 2 cents, and 5 cents (€0.01, €0.02, and €0.05).

Santiago is the site of the University of Santiago de Compostela, established in the early 16th century. The main campus can be seen best from an alcove in the large municipal park in the centre of the city.

Within the old town there are many narrow winding streets full of historic buildings. The new town all around it has less character though some of the older parts of the new town have some big flats in them.

Santiago de Compostela has a substantial nightlife. Both in the new town (a zona nova in Galician, la zona nueva in Spanish or ensanche) and the old town (Galician: a zona vella, Spanish: la zona vieja, trade-branded as zona monumental), a mix of middle-aged residents and younger students maintain a lively presence until the early hours of the morning. Radiating from the centre of the city, the historic cathedral is surrounded by paved granite streets, tucked away in the old town, and separated from the newer part of the city by the largest of many parks throughout the city, Parque da Alameda.

Santiago gives its name to one of the four military orders of Spain: Santiago, Calatrava, Alcántara and Montesa.

One of the most important economic centres in Galicia, Santiago is the seat for organisations like Association for Equal and Fair Trade Pangaea.

Climate

[edit]Under the Köppen climate classification, Santiago de Compostela has a temperate oceanic climate (Cfb) with mild to warm and somewhat dry summers and mild, wet winters. The prevailing winds from the Atlantic and the surrounding mountains combine to give Santiago some of Spain's highest rainfall: about 1,800 millimetres (70.9 in) annually. The winters are mild, despite being far inland and at an altitude of 370 metres (1,210 ft) frosts are only common in December, January and February, with an average of just 13 days per year. Snow is uncommon, with 2-3 snowy days per year.[8] Temperatures above 35 °C (95 °F) are very exceptional.

| Climate data for Santiago de Compostela (1991–2020) (Provisional Normals) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 20.3 (68.5) |

23.2 (73.8) |

27.6 (81.7) |

30.2 (86.4) |

34.0 (93.2) |

37.8 (100.0) |

39.4 (102.9) |

39.0 (102.2) |

39.0 (102.2) |

30.4 (86.7) |

24.2 (75.6) |

23.4 (74.1) |

39.4 (102.9) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 12.3 (54.1) |

13.4 (56.1) |

16.0 (60.8) |

17.3 (63.1) |

19.8 (67.6) |

22.8 (73.0) |

24.8 (76.6) |

25.0 (77.0) |

23.2 (73.8) |

19.6 (67.3) |

14.8 (58.6) |

12.9 (55.2) |

18.5 (65.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 8.9 (48.0) |

9.5 (49.1) |

11.3 (52.3) |

12.5 (54.5) |

15.0 (59.0) |

17.8 (64.0) |

19.6 (67.3) |

19.9 (67.8) |

18.2 (64.8) |

15.3 (59.5) |

11.2 (52.2) |

9.4 (48.9) |

14.1 (57.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 5.4 (41.7) |

5.6 (42.1) |

6.5 (43.7) |

7.7 (45.9) |

10.1 (50.2) |

12.6 (54.7) |

14.4 (57.9) |

14.6 (58.3) |

13.1 (55.6) |

10.9 (51.6) |

7.5 (45.5) |

5.9 (42.6) |

9.5 (49.2) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −7.0 (19.4) |

−9.0 (15.8) |

−5.6 (21.9) |

−3.0 (26.6) |

−2.0 (28.4) |

3.4 (38.1) |

3.4 (38.1) |

1.0 (33.8) |

3.0 (37.4) |

−1.6 (29.1) |

−3.2 (26.2) |

−6.5 (20.3) |

−9.0 (15.8) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 195.8 (7.71) |

151.0 (5.94) |

139.9 (5.51) |

130.0 (5.12) |

109.2 (4.30) |

44.3 (1.74) |

30.6 (1.20) |

45.2 (1.78) |

88.6 (3.49) |

214.0 (8.43) |

193.6 (7.62) |

184.4 (7.26) |

1,526.6 (60.1) |

| Source: Agencia Estatal de Meteorología[9][10] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Santiago de Compostela Airport (1981–2010) altitude 370 metres (1,210 ft) m.a.s.l. Extremes 1944−2021 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 20.3 (68.5) |

23.2 (73.8) |

27.6 (81.7) |

30.2 (86.4) |

34.0 (93.2) |

37.8 (100.0) |

39.4 (102.9) |

39.0 (102.2) |

39.0 (102.2) |

30.4 (86.7) |

24.2 (75.6) |

23.4 (74.1) |

39.4 (102.9) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 11.2 (52.2) |

12.5 (54.5) |

15.0 (59.0) |

16.1 (61.0) |

18.6 (65.5) |

22.2 (72.0) |

24.3 (75.7) |

24.7 (76.5) |

22.8 (73.0) |

18.1 (64.6) |

14.1 (57.4) |

11.9 (53.4) |

17.6 (63.7) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 7.7 (45.9) |

8.3 (46.9) |

10.2 (50.4) |

11.2 (52.2) |

13.6 (56.5) |

16.8 (62.2) |

18.6 (65.5) |

19.0 (66.2) |

17.4 (63.3) |

13.8 (56.8) |

10.4 (50.7) |

8.5 (47.3) |

13.0 (55.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 4.1 (39.4) |

4.1 (39.4) |

5.4 (41.7) |

6.2 (43.2) |

8.5 (47.3) |

11.3 (52.3) |

13.0 (55.4) |

13.3 (55.9) |

11.9 (53.4) |

9.5 (49.1) |

6.7 (44.1) |

5.0 (41.0) |

8.3 (46.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −7.0 (19.4) |

−9.0 (15.8) |

−5.6 (21.9) |

−3.0 (26.6) |

−2.0 (28.4) |

3.4 (38.1) |

3.4 (38.1) |

1.0 (33.8) |

3.0 (37.4) |

−1.6 (29.1) |

−3.2 (26.2) |

−6.5 (20.3) |

−9.0 (15.8) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 210 (8.3) |

167 (6.6) |

146 (5.7) |

146 (5.7) |

135 (5.3) |

72 (2.8) |

43 (1.7) |

57 (2.2) |

107 (4.2) |

226 (8.9) |

217 (8.5) |

261 (10.3) |

1,787 (70.4) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1 mm) | 15.2 | 12.6 | 12.8 | 14.4 | 12.7 | 7.6 | 5.7 | 5.5 | 8.4 | 14.0 | 14.9 | 15.9 | 139.5 |

| Average snowy days | 1.0 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 2.7 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 84 | 79 | 75 | 76 | 76 | 74 | 74 | 74 | 75 | 82 | 86 | 85 | 78 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 93 | 114 | 151 | 165 | 187 | 225 | 243 | 237 | 184 | 132 | 95 | 85 | 1,911 |

| Source: Agencia Estatal de Meteorología[11][10] | |||||||||||||

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

The Obradoiro façade of the grand Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela | |

| Criteria | Cultural: i, ii, vi |

| Reference | 347 |

| Inscription | 1985 (9th Session) |

| Area | 107.59 ha |

| Buffer zone | 216.88 ha |

Administration

[edit]The city is governed by a mayor–council form of government. Following the 2023 Spanish local elections the mayor of Santiago is Goretti Sanmartín, of BNG.

2015 city council elections results

[edit]| Party | Vote | Seats | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Votes | % | ±pp | Won | +/− | ||

| Compostela Aberta (CA)[12] | 16,327 | 34.58 | 10 | |||

| People's Party (PP) | 15,869 | 33.61 | 9 | |||

| Socialists' Party of Galicia-Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSdeG-PSOE) | 6,919 | 14.65 | 4 | |||

| Galician Nationalist Bloc-Open Assemblies (BNG) | 3,277 | 6.94 | 2 | |||

| Citizens | 2,285 | 4.84 | New | 0 | ±0 | |

| Commitment to Galicia-Transparent Municipalities (CxG-CCTT) | 1,112 | 2.35 | New | 0 | ±0 | |

| Solidarity and Internationalist Self-management (SAIn) | 301 | 0.64 | 0 | ±0 | ||

| Converxencia XXI (C21) | 139 | 0.29 | 0 | ±0 | ||

| Blank ballots | 991 | 2.10 | ||||

| Total | 47,220 | 100.00 | 25 | ±0 | ||

| Valid votes | 47,220 | 98.46 | ||||

| Invalid votes | 738 | 1.54 | ||||

| Votes cast / turnout | 47,958 | 61.13 | ||||

| Abstentions | 30,492 | 38.87 | ||||

| Registered voters | 78,450 | |||||

| Source: Ministry of the Interior | ||||||

Population

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1842 | 22,749 | — |

| 1857 | 26,938 | +18.4% |

| 1877 | 23,629 | −12.3% |

| 1887 | 22,574 | −4.5% |

| 1900 | 24,317 | +7.7% |

| 1910 | 24,660 | +1.4% |

| 1920 | 27,341 | +10.9% |

| 1930 | 39,620 | +44.9% |

| 1940 | 43,815 | +10.6% |

| 1950 | 52,675 | +20.2% |

| 1960 | 57,173 | +8.5% |

| 1970 | 65,270 | +14.2% |

| 1981 | 82,404 | +26.3% |

| 1991 | 87,807 | +6.6% |

| 2001 | 90,188 | +2.7% |

| 2011 | 95,397 | +5.8% |

| 2021 | 97,798 | +2.5% |

| Source: National Statistics Institute[13] | ||

The population of the city in 2019 was 96,260 inhabitants, while the metropolitan area reaches 178,695.

In 2010 there were 4,111 foreigners living in the city, representing 4.3% of the total population. The main nationalities are Brazilians (11%), Portuguese (8%) and Colombians (7%).

By language, according to 2008 data, 21.17% of the population always speak in Galician, 15% always speak in Spanish, 31% mostly in Galician and the 32.17% mostly in Spanish.[14] According to a Xunta de Galicia 2010 study the 38.5% of the city primary and secondary education students had Galician as their mother tongue.[15]

History

[edit]

The area of Santiago de Compostela was a Roman cemetery by the 4th century[16] and was occupied by the Suebi in the early 5th century, when they settled in Galicia and Portugal during the initial collapse of the Roman Empire. The area was later attributed to the bishopric of Iria Flavia in the 6th century, in the partition usually known as Parochiale Suevorum, ordered by King Theodemar. In 585, the settlement was annexed along with the rest of Suebi Kingdom by Leovigild as the sixth province of the Visigothic Kingdom.

Possibly raided from 711 to 739 by the Arabs,[17][18] the bishopric of Iria was incorporated into the Kingdom of Asturias c. 750.[19][20][21] At some point between 818 and 842,[22] during the reign of Alfonso II of Asturias,[23][24] bishop Theodemar of Iria (d. 847) claimed to have found some remains which were attributed to Saint James the Greater. This discovery was accepted in part because Pope Leo III[25] and Charlemagne—who had died in 814—had acknowledged Asturias as a kingdom and Alfonso II as king, and had also crafted close political and ecclesiastic ties.[26] Around the place of the discovery a new settlement and centre of pilgrimage emerged, which was known to the author Usuard in 865[27] and which was called Compostella by the 10th century.

The devotion to Saint James of Compostela was just one of many arising throughout northern Iberia during the 10th and 11th centuries, as rulers encouraged their own region-specific devotions, such as Saint Eulalia in Oviedo and Saint Aemilian in Castile.[28] After the centre of Asturian political power moved from Oviedo to León in 910, Compostela became more politically relevant, and several kings of Galicia and of León were acclaimed by the Galician noblemen and crowned and anointed by the local bishop at the cathedral, among them Ordoño IV in 958,[29] Bermudo II in 982, and Alfonso VII in 1111, by which time Compostela had become capital of the Kingdom of Galicia. Later, 12th-century kings were also sepulchered in the cathedral, namely Fernando II and Alfonso IX, last of the Kings of León and Galicia before both kingdoms were united with the Kingdom of Castile.

During this same 10th century and in the first years of the 11th century Viking raiders tried to assault the town[30]—Galicia is known in the Nordic sagas as Jackobsland or Gallizaland—and bishop Sisenand II, who was killed in battle against them in 968,[31] ordered the construction of a walled fortress to protect the sacred place. In 997 Compostela was assaulted and partially destroyed by Ibn Abi Aamir (known as al-Mansur), Andalusian leader accompanied in his raid by Christian lords, who all received a share of the booty.[32][33]. However, the Andalusian commander showed no interest in the alleged relics of St James. In response to these challenges bishop Cresconio, in the mid-11th century, fortified the entire town, building walls and defensive towers.

According to some authors, by the middle years of the 11th century the site had already become a pan-European "place of peregrination",[34] while others maintain that the devotion to Saint James was before 11-12th centuries an essentially Galician affair, supported by Asturian and Leonese kings to win over faltering Galician loyalties.[28] Santiago would become in the course of the following century a main Catholic shrine second only to Rome and Jerusalem. In the 12th century, under the impulse of bishop Diego Gelmírez, Compostela became an archbishopric, attracting a large and multinational population. Under the rule of this prelate, the townspeople rebelled, headed by the local council, beginning a secular tradition of confrontation by the people of the city—who fought for self-government—against the local bishop, the secular and jurisdictional lord of the city and of its fief, the semi-independent Terra de Santiago ("land of Saint James"). The culminating moment in this confrontation was reached in the 14th century, when the new prelate, the Frenchman Bérenger de Landore, treacherously executed the counselors of the city in his castle of A Rocha Forte ("the strong rock, castle"), after inviting them for talks.

Santiago de Compostela was captured and sacked by the French during the Napoleonic Wars; as a result, the remains attributed to the apostle were lost for near a century, hidden inside a cist in the crypts of the cathedral of the city.

The excavations conducted in the cathedral during the 19th and 20th centuries uncovered a Roman cella memoriae or martyrium, around which grew a small cemetery in Roman and Suevi times which was later abandoned. This martyrium, which proves the existence of an old Christian holy place, has been sometimes attributed to Priscillian, although without further proof.[35]

Economy

[edit]Santiago's economy, although still heavily dependent on public administration (i.e. being the headquarters of the autonomous government of Galicia), cultural tourism, industry, and higher education through its university, is becoming increasingly diversified. New industries such as timber transformation (FINSA), the automotive industry (UROVESA), and telecommunications and electronics (Blusens and Televés) have been established. Banco Gallego, a banking institution owned by Novacaixagalicia, has its headquarters in downtown rúa do Hórreo.

Tourism is very important thanks to the Way of St. James, particularly in Holy Compostelan Years (when the Feast of Saint James falls on a Sunday). Following the Xunta's considerable investment and hugely successful advertising campaign for the Holy Year of 1993, the number of pilgrims completing the route has been steadily rising. More than 272,000 pilgrims made the trip during the course of the Holy Year of 2010. Following 2010, the next Holy Year will not be for another 11 years when St James feast day again falls on a Sunday. Outside of Holy Years, the city still receives a remarkable number of pilgrims. In 2013, 215,880 people completed the pilgrimage. In 2014, there were 237,983 persons. In 2015, there were 262,513 persons and in 2016, there were 277,854 persons.[36]

Editorial Compostela owns daily newspaper El Correo Gallego, a local TV, and a radio station. Galician-language online news portal Galicia Hoxe is also based in the city. Televisión de Galicia, the public broadcaster corporation of Galicia, has its headquarters in Santiago.

Way of St. James

[edit]

During medieval times, the Santiago de Compostela pilgrimage emerged as one of the most significant Christian journeys in Europe, attracting thousands of pilgrims seeking spiritual redemption and fulfillment. Believed to be the final resting place of Saint James the Apostle, the pilgrimage route traversed many countries and scenic locations. [37] The pilgrimage not only fostered spiritual growth but also facilitated cultural exchange, as towns along the route thrived with the influx of visitors, leading to the construction of churches,[38] and further development of the towns. This sacred journey symbolized a profound devotion to faith, enduring trials, and the hope of divine grace. A symbol of the Pilgrimage is the scallop shell, as seen in a sculpture, depicted below, in Santo Domingo de Silos, in which Jesus is shown as a pilgrim with a satchel that is embroidered with the scallop shell. The Scallop shell comes from a legend about St. James’s arrival: he frightened a horse, scaring it into the sea, and the horse reemerged with the shell covering itself.[39]

Santiago de Compostela’s pilgrimage, known as the Camino de Santiago, is one of the world's most significant and historical Christian pilgrimages.[40] This sacred journey leads to the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela in the Galicia region of northwest Spain, where the remains of Saint James the Apostle are believed to be buried. The pilgrimage dates back to the Middle Ages and continues to draw thousands of pilgrims annually from all corners of the globe. Participants embark on various routes, the most popular being the Camino Francés,[41] traversing hundreds of kilometers on foot, by bicycle, or even on horseback. The journey is not just a physical challenge but also a profound spiritual and introspective experience, offering a sense of community, personal reflection, and fulfillment. Along the way, pilgrims pass through diverse landscapes and historic towns and encounter symbols of faith and support.[42]

The legend that St. James found his way to the Iberian Peninsula and had preached there is one of a number of early traditions concerning the missionary activities and final resting places of the apostles of Jesus. Although the 1884 Bull of Pope Leo XIII Omnipotens Deus accepted the authenticity of the relics at Compostela, the Vatican remains uncommitted as to whether the relics are those of Saint James the Greater, while continuing to promote the more general benefits of pilgrimage to the site. Pope Benedict XVI undertook a ceremonial pilgrimage to the site on his visit to Spain in 2010.[43]

Establishment of the shrine

[edit]

The 1,000-year-old pilgrimage to the shrine of St. James in the Santiago de Compostela Cathedral is known in English as the Way of St. James and in Spanish as the Camino de Santiago. Over 200,000 pilgrims travel to the city each year from points all over Europe and other parts of the world. The pilgrimage has been the subject of many books, television programmes, and films, notably Brian Sewell's The Naked Pilgrim produced for the British television channel Channel 5 and the Martin Sheen/Emilio Estevez collaboration The Way.

Legends

[edit]According to a tradition that can be traced back at least to the 12th century, when it was recorded in the Codex Calixtinus, Saint James decided to return to the Holy Land after preaching in Galicia. There he was beheaded, but his disciples got his body to Jaffa, where they found a marvelous stone ship which miraculously conducted them and the apostle's body to Iria Flavia, back in Galicia. There, the disciples asked the local pagan queen Loba ('She-wolf') for permission to bury the body; she, annoyed, decided to deceive them, sending them to pick a pair of oxen she allegedly had by the Pico Sacro, a local sacred mountain where a dragon dwelt, hoping that the dragon would kill the Christians, but as soon as the beast attacked the disciples, at the sight of the cross, the dragon exploded. Then the disciples marched to collect the oxen, which were actually wild bulls which the queen used to punish her enemies; but again, at the sight of the Christian's cross, the bulls calmed down, and after being subjected to a yoke they carried the apostle's body to the place where now Compostela is. The legend was again referred with minor changes by the Czech traveller Jaroslav Lev of Rožmitál, in the 15th century.[44]

The relics were said to have been later rediscovered in the 9th century by a hermit named Pelagius, who after observing strange lights in a local forest went for help after the local bishop, Theodemar of Iria, in the west of Galicia. The legend affirms that Theodemar was then guided to the spot by a star, drawing upon a familiar myth-element, hence "Compostela" was given an etymology as a corruption of Campus Stellae, "Field of Stars."

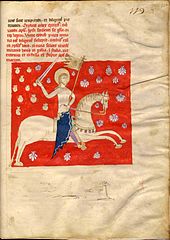

In the 15th century, the red banner which guided the Galician armies to battle, was still preserved in the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela, in the centre Saint James riding a white horse and wearing a white cloak, sword in hand:[45] The legend of the miraculous armed intervention of Saint James, disguised as a white knight to help the Christians when battling the Muslims, was a recurrent myth during the High Middle Ages.

Pre-Christian legends

[edit]As the lowest-lying land on that stretch of coast, the city's site took on added significance. Legends supposed of Celtic origin made it the place where the souls of the dead gathered to follow the sun across the sea. Those unworthy of going to the Land of the Dead haunted Galicia as the Santa Compaña or Estadea.

In popular culture

[edit]Santiago de Compostela is featured prominently in the 1988 historical fiction novel Sharpe's Rifles, by Bernard Cornwell, which takes place during the French Invasion of Galicia, January 1809, during the Napoleonic Wars.

The music video for Una Cerveza, by Ráfaga, is set in the historic part of Santiago de Compostela.

A pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela provides the narrative framework of the Luis Buñuel film La Voie lactée (The Milky Way).

A mystic pilgrimage was portrayed in the autobiography and romance The Pilgrimage ("O Diário de um Mago") of Brazilian writer Paulo Coelho, published in 1987.

Main sights

[edit]- Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela

- University of Santiago de Compostela

- Pazo de Raxoi – city hall and office of the President of the Xunta of Galicia

- 12th century Colexiata de Santa María do Sar

- 16th century Baroque Abbey of San Martín Pinario

- 17th century Convent and Church of San Francisco

- Centro Galego de Arte Contemporánea (Galician Center for Contemporary Art), designed by Alvaro Siza Vieira

- City of Culture of Galicia, designed by Peter Eisenman

- Muralla de Santiago de Compostela

- Parque da Alameda (Alameda Park)

- Parque de Carlomagno (Carlomagno Park)

- Parque de San Domingos de Bonaval, redesigned by Eduardo Chillida and Alvaro Siza Vieira

Transport

[edit]

Santiago de Compostela is served by Santiago de Compostela Airport and a Renfe rail service.

Airport

[edit]Santiago de Compostela Airport is the 2nd busiest airport in northern Spain after Bilbao Airport. The airport is located in the parish of Lavacolla, 12 km from the city center and handled 2,903,427 passengers in 2019.

Railway

[edit]Santiago de Compostela railway station is linked to the Spanish High Speed Railway Network. Madrid is reached in 3 hours.

Porto can also be reached in less than 5 hours changing to the Celta train in Vigo.[46]

On 24 July 2013 there was a serious rail accident near the city in which 79 people died and at least 130 were injured when a train derailed on a bend as it approached Compostela station.[47]

Sports teams

[edit]- SD Compostela (football) - 4 seasons in La Liga

- Obradoiro CAB (basketball) - 11 seasons in Liga ACB

- Santiago Futsal (futsal) -

15 seasons in LNFS

- Santiago Black Ravens (American football) - 2 seasons in LNFA and 2 seasons in LPFA

- Arteal Tenis de Mesa (table tennis) - 12 seasons in SDTM

- Escudería Compostela (motorsport) - Rally Botafumeiro organizer

- Santiago Rugby Club (rugby union)

- Estrela Vermelha FG (Gaelic football)

Notable people

[edit]

- Bernal de Bonaval, 13th-century troubadour in the Kingdom of Galicia who wrote in the Galician-Portuguese language

- Sancho de Andrade de Figueroa (1632–1702), Roman Catholic prelate, Bishop of Quito (1688–1702) and Bishop of Ayacucho o Huamanga (1679–1688)

- Juan Antonio García de Bouzas (c.1680–1755), Baroque painter, his principal works are in the churches at Santiago

- Eugenio Montero Ríos (1832–1914), politician, served briefly as Prime Minister of Spain in 1905

- Rosalía de Castro (1837–1885), romanticist writer and poet[48]

- Antonio Machado Álvarez (1848–1893) known as Demófilo, writer, anthropologist and Spanish folklorist

- Narcisa Pérez Reoyo (1849–1876), writer

- Modesto Brocos (1852–1936), Brazilian painter, designer and engraver

- Carmen Babiano Méndez-Núñez (1852–1914), painter and a pioneer in feminine art

- Manuel Maria Puga y Parga aka "Picadillo" (1874–1918), culinary writer and gastronome, popularized traditional Galician cooking

- José Robles (1897–1937), academic, left-wing activist, born to an aristocratic family, went into exile in the USA

- Maruxa and Coralia Fandiño Ricart (1898–1980; 1914–1983), local public figures

- Juan Sáenz-Díez García (1904–1990), entrepreneur and Carlist politician

- Xerardo Fernández Albor (1917–2018), physician and politician, president of Galicia from 1981 to 1987

- Isaac Díaz Pardo (1920–2012), intellectual, painter, ceramist, and businessman

- Xohana Torres (1931–2017), writer, poet, playwright, and member of the Royal Galician Academy

- Adela Akers (born 1933), textile and fiber artist, raised in Peru and Cuba, now lives in Guerneville, California

- Xosé Manuel Beiras (born 1936), politician, economist, writer and intellectual

- Roberto Vidal Bolaño (1950–2002), playwright and actor, celebrated by Galician Literature Day in 2013

- Ana Romero Masiá (born 1952), historian, archaeologist and academic

- Mariano Rajoy (born 1955), politician, Prime Minister of Spain from 2011 to 2018

- Suso de Toro (born 1956), writer of more than twenty novels and plays in Galician

- Carlos Ferrás Sexto (born 1965), geographer and academic

- Octavio Vázquez (born 1972), composer of classical music

- Yolanda Castaño (born 1977), painter, literary critic and poet

- Roi Méndez (born 1993), singer and guitarist[49]

Sport

[edit]

- Andrés Domínguez Candal (1918–1978) aka Pierita, footballer

- Carlos Gil Pérez (1931–2009), athletics coach

- José Luis Veloso (1937–2019), footballer, 278 pro appearances

- Tomás Reñones (born 1960) known as Tomás, footballer, nearly 500 pro appearances

- Moncho Fernández (born 1969), basketball manager and coach

- Emilio José Viqueira (born 1974), footballer who made 454 pro appearances

- Manuel Castiñeiras (born 1979), footballer, over 300 pro appearances

- Rubén González Rocha (born 1982), known as Rubén, football central defender

- Borja Golan (born 1983), professional squash player who represents Spain

- Iván Carril (born 1985), footballer

- Verónica Boquete (born 1987), footballer

- José Ángel Antelo (born 1987), basketball player

- Alberto Manuel Domínguez Rivas (born 1988) known as Alberto, football goalkeeper

- Borja Iglesias (born 1993), footballer for Real Betis

International relations

[edit]Twin towns/Sister cities

[edit]Santiago de Compostela is twinned with:[50]

Assisi, Italy (2008)[51]

Assisi, Italy (2008)[51] Barcelona, Spain[52]

Barcelona, Spain[52] Braga, Portugal[53]

Braga, Portugal[53] Buenos Aires, Argentina (1980s)[54]

Buenos Aires, Argentina (1980s)[54] Cáceres, Spain[55]

Cáceres, Spain[55] Caracas, Venezuela[56]

Caracas, Venezuela[56] Coimbra, Portugal (1994)[57]

Coimbra, Portugal (1994)[57] Córdoba, Spain[58]

Córdoba, Spain[58] Mashhad, Iran[59]

Mashhad, Iran[59] Las Piedras, Uruguay (2010)

Las Piedras, Uruguay (2010) Le Puy-en-Velay, France[60]

Le Puy-en-Velay, France[60] Oviedo, Spain[61]

Oviedo, Spain[61] Pisa, Italy (2010)[62]

Pisa, Italy (2010)[62] Qom, Iran[63]

Qom, Iran[63] Qufu, People's Republic of China[64]

Qufu, People's Republic of China[64] Rennes, France (2010)[65]

Rennes, France (2010)[65] Santiago, Chile

Santiago, Chile Santiago de Cali, Colombia

Santiago de Cali, Colombia Santiago de Cuba, Cuba

Santiago de Cuba, Cuba Santiago de las Vegas, Cuba

Santiago de las Vegas, Cuba Santiago de los Caballeros, Dominican Republic (2004)

Santiago de los Caballeros, Dominican Republic (2004) Santiago de Querétaro, Mexico (2005)[66]

Santiago de Querétaro, Mexico (2005)[66] Santiago de Veraguas, Panama

Santiago de Veraguas, Panama Santiago do Cacém, Portugal (1980s)[60]

Santiago do Cacém, Portugal (1980s)[60] Santiago Tuxtla, Mexico

Santiago Tuxtla, Mexico São Paulo, Brazil[67]

São Paulo, Brazil[67]

See also

[edit]- Auditorio Monte do Gozo

- Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela

- Camino de Santiago

- Música en Compostela

- Order of Santiago

- Santiago de Compostela derailment

- As Orfas

- Klaus Schäfer, Various routes to Santiago de Compostela

- Coat of arms of Santiago de Compostela

- List of municipalities in A Coruña

Notes

[edit]- ^ Pronunciation:

- English: /ˌsæntiˈɑːɡoʊ də ˌkɒmpəˈstɛlə/[2]

- Spanish: [sanˈtjaɣo ðe komposˈtela] ⓘ

- Galician: [santiˈaɣʊ ðɪ komposˈtɛlɐ]

References

[edit]- ^ Municipal Register of Spain 2018. National Statistics Institute.

- ^ "Santiago". Dictionary.com Unabridged (Online). n.d.

- ^ Lopez Alsina, Fernando (2013). La ciudad de Santiago de Compostela en la Alta Edad Media (2. corr ed.). Santiago de Compostela: Consorcio de Santiago. ISBN 9788415876694.

- ^ Encyclopaedia Britannica (1823), p. 500.

- ^ Fletcher (1984), p. 59.

- ^ a b c d Stokstad, Marilyn (1978). Santiago de Compostela in the age of the great pilgrimages. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 6−8. ISBN 978-0806114545.

- ^ "THE WAY | Fundación Arousa. Foundation Arousa. Año Santo Compostelano. Año Jacobeo. Xacobeo 2021. The Route of the sea of Arousa and river Ulla".

- ^ "Santiago de Compostela Aeropuerto: Santiago de Compostela Aeropuerto - State Meteorological Agency - AEMET - Spanish Government".

- ^ "AEMET OpenData". Agencia Estatal de Meteorologia. Retrieved 14 May 2024.

- ^ a b "Extreme values. Santiago de Compostela Aeropuerto".

- ^ "Standard climate values. Santiago de Compostela Aeropuerto".

- ^ Results compared with the combined results of United Left and Candidatura do Povo in 2011.

- ^ "Changes in the municipalities in the population census since 1842" (in Spanish). National Statistics Institute.

- ^ "Instituto Galego de Estatística – 2008 – Uso da lingua nos grandes concellos – Santiago de Compostela".

- ^ "'Os datos secretos do galego': Así responderon as familias á consulta lingüística da Xunta". 15 December 2016.

- ^ Fletcher (1984), pp. 57–59.

- ^ Gallichan (1912), pp. 36−37.

- ^ Encyclopaedia Britannica (1823), p. 496.

- ^ Gallichan (1912), pp. 26−27.

- ^ Atlas of Medieval History Colin Mc Evedy (Penguin Books) [1961]. pp. 46.

- ^ Encyclopaedia Britannica (1823), p. 499.

- ^ Fletcher (1984).

- ^ Gallichan (1912), pp. 26−25.

- ^ Almanach de Gotha [Almanac of Gotha] (in French). Gotha, Germany: Justus Perthes. 1828. pp. 28–29. OCLC 600124268. From the collections of the Getty Research Institute. (Published annually from 1764 to 1944)

- ^ Gallichan (1912), pp. 24−25.

- ^ Collins (1983), p. 232.

- ^ Fletcher (1984), p. 56.

- ^ a b Collins (1983), p. 238.

- ^ Portela Silva, Ermelindo (2001). García II de Galicia, el rey y el reino (1065–1090). Burgos: La Olmeda. p. 165. ISBN 84-89915-16-4.

- ^ Fletcher (1984), p. 23.

- ^ Morales Romero, Eduardo (1997). Os viquingos en Galicia. Santiago de Compostela: USC. p. 125. ISBN 84-8121-661-5.

- ^ Collins (1983), p. 199.

- ^ {{A fictionalized account of Almanzor's raid on Compostela is part of the plot of the historical novel The Long Ships}}

- ^ Fletcher (1984), p. 53.

- ^ Fletcher (1984), pp. 59–60.

- ^ "Camino de Santiago Statistics End 2016 Pilgrim Numbers Walking Camino". caminoadventures.com. 8 August 2017. Retrieved 21 November 2017.

- ^ Melczer, William; Melczer, William (1993). The pilgrim's guide to Santiago de Compostela: first English translation, with introduction, commentaries, and notes. New York: Italica Press. ISBN 978-0-934977-25-8.

- ^ Bell, Adrian R.; Dale, Richard S. (2011). "The Medieval Pilgrimage Business". Enterprise & Society. 12 (3): 601–627. doi:10.1093/es/khr014. ISSN 1467-2227. JSTOR 23701445.

- ^ Fitzpatrick, Martin (2010). "Pilgrimage to Santiago De Compostela". Archaeology Ireland. 24 (4): 14–17. ISSN 0790-892X. JSTOR 40961787.

- ^ Rudolph, Conrad (2004). Pilgrimage to the end of the world: the road to Santiago de Compostela. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-73125-4.

- ^ "French Way", Wikipedia, 28 October 2024, retrieved 6 November 2024

- ^ Graham, Brian; Murray, Michael (1997). "The spiritual and the profane: the pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela". Ecumene. 4 (4): 389–409. doi:10.1177/147447409700400402. ISSN 0967-4608. JSTOR 44251953.

- ^ "Apostolic Journey to Santiago de Compostela and Barcelona: Welcoming ceremony at the International Airport of Santiago de Compostela (November 6, 2010) – BENEDICT XVI". w2.vatican.va.

- ^ Garrido Bugarín, Gustavo A. (1994). Aventureiros e curiosos : relatos de viaxeiros estranxeiros por Galicia, séculos XV – XX. Vigo: Ed. Galaxia. pp. 35–37. ISBN 84-7154-909-3.

- ^ Garrido Bugarín, Gustavo A. (1994). Aventureiros e curiosos : relatos de viaxeiros estranxeiros por Galicia, séculos XV – XX. Vigo: Ed. Galaxia. p. 40. ISBN 84-7154-909-3.

- ^ "Porto to Santiago de Compostela by train".

- ^ Spain train crash: Driver formally detained, BBC News 26 July 2013

- ^ Consello da Cultura Galega (20 July 1985). Actas do Congreso Internacional de Estudios sobre Rosalía de Castro e o Seu Tempo. Vol. 1. Univ Santiago de Compostela. p. 81. ISBN 9788471914002.

- ^ Aldegunde, C. (23 October 2017). "Miriam, Luis y Roi, así son los concursantes gallegos de "Operación Triunfo 2017"". La Voz de Galicia (in Spanish). Retrieved 8 December 2018.

- ^ "Todos los Santiagos se hermanan" (in Spanish). El Correo Gallego. 23 January 2015. Retrieved 15 November 2023.

- ^ "Documento Unico di Programmazione 2016-2021 – DUP" (PDF) (in Italian). Assisi. October 2016. p. 63,78. Retrieved 13 November 2023.

- ^ "Concello de Santiago: Proyecto de red de ciudades hermanadas Santiago-Une" (PDF) (in Spanish). culturaydeporte.gob.es. Retrieved 14 November 2023.

- ^ "Inícianse os trámites para o irmandamento de Compostela coa cidade portuguesa de Braga" (in Galician). Council of Santiago de Compostela. Retrieved 14 November 2023.

- ^ "Convenios Internacionales" (in Spanish). City of Buenos Aires. Retrieved 14 November 2023.

- ^ "Se cumplen 50 años desde que Cáceres y Santiago de Compostela son hermanas" (in Spanish). Hoy. 15 October 2023. Retrieved 15 November 2023.

- ^ "Os irmandamentos en Galicia: Globalización, redes e goberno local" (PDF) (in Galician). IGADI. Retrieved 15 November 2023.

- ^ "Cidades Geminadas e Acordos de Cooperação" (in Portuguese). Coimbra. Retrieved 13 November 2023.

- ^ "Las 12 hermanas de Córdoba" (in Spanish). Diario Córdoba. 10 February 2020. Retrieved 14 February 2020.

- ^ "Town Twinning". Mashhad. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- ^ a b "Tres calles de San Marcos recibirán el nombre de ciudades hermanadas con Compostela" (in Spanish). La Voz de Galicia. 16 December 2008. Retrieved 14 November 2023.

- ^ "Oviedo se hermanará con la ciudad portuguesa de Sintra en San Mateo" (in Spanish). El Comercio. 20 May 2018. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- ^ "Gemellaggi" (in Italian). Pisa. Retrieved 13 November 2023.

- ^ "Qom". Toiran.com. Retrieved 13 November 2023.

- ^ "QuFu (China) y Santiago de Compostela preparan un acuerdo de hermanamiento" (in Spanish). Europa Press. 22 June 2006. Retrieved 15 November 2023.

- ^ "Compostela se hermana con la ciudad francesa de Rennes, adonde lleva la muestra "Santiago Une"" (in Spanish). La Voz de Galicia. 19 June 2010. Retrieved 15 November 2023.

- ^ "Santiago de Compostela y de Querétaro, hermanadas" (in Spanish). La Voz de Galicia. 11 March 2017. Retrieved 15 November 2023.

- ^ "Cidades-Irmãs de São Paulo" (in Portuguese). São Paulo. Retrieved 26 November 2022.

Sources

[edit]This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Santiago de Compostela". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 24 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 191–192.

- Collins, Roger (1983). Early Medieval Spain. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-22464-8.

- "Spain". Encyclopaedia Britannica, or, A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, and Miscellaneous Literature. Vol. 19 (Sixth ed.). Edinburgh: Archibald Constable. 1823. pp. 482−544.

- Fletcher, Richard A. (1984). Saint James's Catapult: The Life and Times of Diego Gelmírez of Santiago de Compostela. Oxford: Clarendon. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-19-822581-2. OCLC 563022412.

- Gallichan, Catherine Gasquoine (1912). The story of Santiago de Compostela;. London: Dent.

Further reading

[edit]- Meakin, Annette M. B. (1909). Galicia. The Switzerland of Spain. London: Methuen & Co.