Two-gospel hypothesis

| Griesbach hypothesis | |

| |

| Theory Information | |

|---|---|

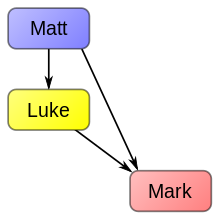

| Order | Matt Luke Mark |

| Additional Sources | No additional sources |

| Gospels' Sources | |

| Mark | Matt, Luke |

| Luke | Matt |

| Theory History | |

| Originator | Henry Owen |

| Originating Work | On Dispensing with Q |

| Origination Date | 1764 |

| Proponents | Johann Jakob Griesbach Friedrich Andreas Stroth William R. Farmer |

The two-gospel hypothesis or Griesbach hypothesis is that the Gospel of Matthew was written before the Gospel of Luke, and that both were written earlier than the Gospel of Mark.[1] It is a proposed solution to the synoptic problem, which concerns the pattern of similarities and differences between the three Gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke. The hypothesis is generally first credited to Johann Jakob Griesbach writing in the 1780s; it was introduced in its current form by William R. Farmer in 1964 and given its current designation of two-gospel hypothesis in 1979.

The two-gospel hypothesis contrasts with the two-source hypothesis, the most popular and accepted scholarly hypothesis. Supporters say that it does not require lost sources like the Q source and was supported by the early Church. Proponents of the two-gospel hypothesis generally also support the traditional claims of authorship as accurate to disciples and their direct associates, which implies the gospels were written comparatively soon after Jesus's death, rather than the later dates of authorship supported by other schools of thought.[2]

Overview

[edit]

The hypothesis states that Matthew was written first, while Christianity was still centered in Jerusalem, to calm the hostility between Jews and Christians. After Matthew, as the church expanded beyond the Holy Land, Luke wrote a gospel with an intended audience of Gentiles. Since neither Luke (nor his associate Paul) were eyewitnesses of Jesus, Peter gave public testimonies that validated Luke's gospel. These public speeches were transcribed into Mark's gospel, as recorded by the early Church father Irenaeus. Paul then allowed Luke's gospel to be published.[3]

The proposal suggests that Matthew was written by the apostle Matthew, probably in the 40s AD. At the time, the church had yet to extend outside of Jerusalem. The primary political problem within the church community was caused by the fact that Jewish authorities were outright hostile to Jesus and his followers. Matthew wrote his account in order to show that Jesus was actually the fulfillment of what Jewish scripture had prophesied. It has been long recognized that Matthew is the most "Jewish" of the gospels. It, for example, heavily references Jewish scripture and Jewish history.[4]

When Stephen was martyred, as recorded in the Book of Acts, the disciples scattered beyond Jerusalem into Gentile (mostly Greek but also Syriac) towns. There they began preaching, and a large number of pagans in Antioch became Christians. By the mid 50s, Paul, who converted and claimed the title of "Apostle to the Gentiles" realized the need for a gospel specifically to the Gentiles. This gospel would deemphasize Mosaic Law and recent Jewish history in order to appeal to Greeks and Romans. Paul commissioned his associate, Luke, who consulted the Gospel of Matthew as well as other sources. Once the gospel had been written, its publication was delayed, however. Paul decided that he needed Peter's public testimony as to its accuracy, since neither Paul nor Luke had known Jesus before Jesus's execution.[5]

Paul asked Peter, who was the leader of the Apostles, to testify that Luke's account was accurate. According to early church sources, Peter gave a series of speeches to senior Roman army officers. Due to the commonality between Mark and Luke, these speeches would have constituted Peter's public "seal of approval" upon Luke's gospel. These church sources suggest that Peter was ambivalent when Mark asked him if he could write down the words of the speeches. However, since the Roman officers who heard the speeches liked them, they asked for copies, and so Mark made fifty copies of Peter's speeches. These copies began circulating, and became Mark's gospel. Only after the speeches by Peter were made (and Mark's transcriptions began circulating) did Paul feel confident enough to publish Luke's gospel.[6]

The two-gospel hypothesis assumes that Peter made sure that his speeches agreed with both Matthew and the still unpublished Luke. Since Matthew was the primary source for Luke, and Matthew's gospel (the only published gospel at the time) would have been well known to Peter, he mostly would have preached on the contents of Matthew. Knowing Matthew better than Luke, Peter was more likely to mention details found in Matthew and not Luke than vice versa. This would explain why there are more details found in Mark and Matthew but not Luke than there are details found in Mark and Luke but not Matthew. It also explains why Mark is so much shorter than Matthew and Luke, is more anecdotal and emotional, is less polished, and why only it begins immediately with Jesus' public ministry. Peter was giving public speeches as to what he saw, and never intended his speeches to become a full gospel. This was asserted by early church historians, and explains why there are so few commentaries on Mark (as opposed to Matthew, Luke and John) until a relatively late date. It appears to have been considered the least important gospel in the early church.[7]

Contrasted with the two-source hypothesis

[edit]Proponents generally separate arguments made from the text of the gospels themselves ("internal evidence") and evidence from preserved writings of the early church ("external evidence"). For example, early church documents claim that Mark's Gospel was created after Mark made fifty copies of a series of speeches that Peter had given in Rome. The two-gospel hypothesis leans very heavily on this external evidence: it embraces the views of the early church, and claims that a strong reason needs to be provided to justify dismissing the traditions of the early Church maintained over the authorship of the gospels. The two-source hypothesis, in contrast, is based largely on the internal evidence for Marcan priority.[8] Since the two-source hypothesis does not accept the conjecture of the early church, it follows from internal evidence (such as the shortness of Mark) and logic (e.g. 'why would Mark write a shorter version of a gospel in existence?')[9]

Approximately 25% of Matthew and 25% of Luke are identical, but are not found in Mark. This has been explained in the two-source hypothesis as coming from the hypothetical Q document. By the two-gospel hypothesis, this material was copied by Luke from Matthew, but not testified to by Mark because Peter had not seen it. Proponents of later dates of authorship (due to seeming familiarity with the destruction of the Temple of Jerusalem in the First Jewish-Roman War in 70 AD in passages such as Mark 13) state that information unique to Matthew ("M") and Luke ("L") came from unknown sources. The two-gospel hypothesis, by placing the authorship of the gospels earlier, assumes "M" to be mostly Saint Matthew's eyewitness testimony and "L" to be eyewitness account interviewed by Luke mentioned in the first verses of Luke's gospel. The two-gospel theory is more of a conjecture, as it depends on assuming the accounts of the early church of Matthean priority to be correct, despite there being some good scholarly reasons for skepticism, most notably the long time gaps between the creation of the gospels and the earliest surviving accounts of their authors.

Scholarly history

[edit]

The Church Fathers settled on Matthaean priority themselves, but kept to the order seen in the New Testament: Matthew, Mark, Luke, then John. This would later be referred to as the Augustinian hypothesis. The Monarchian Prologues, from around 380, state that Mark used both Matthew and Luke.[10]

The first major proponent of something like a Matthew-Luke-Mark ordering was Johann Jakob Griesbach. The Griesbach hypothesis is similar to the modern two-gospel hypothesis. However, unlike the two-gospel hypothesis, the Griesbach hypothesis is principally a literary hypothesis. What came to be labeled the Griesbach Hypothesis was anticipated by the Welsh scholar Henry Owen (1716–1795) in a piece he published in 1764, and by Friedrich Andreas Stroth (1750–1785) in an article he published anonymously in 1781. Griesbach (1745–1812), to whom this source hypothesis was first accredited, alluded to his conclusion that Matthew wrote the first of the canonical gospels and that Luke, not Mark, made first use of Matthew in composing the second of the canonical gospels in an address celebrating the Easter season at the University of Jena in 1783. Later, for similar Whitsun programs at Jena (1789–1790), Griesbach published a more detailed "Demonstration that the Whole Gospel of Mark is Excerpted from the Narratives of Matthew & Luke."

Griesbach's theory was what German scholars came to call a "utilization hypothesis." Griesbach's main support for his thesis lies in passages where Matthew and Luke agree over and against Mark (e.g. Matthew 26:68; Luke 22:64; Mark 14:65), the so-called Minor Agreements.

A related theory has Luke drawing not directly from Matthew, but from a common source, seen as a proto-Matthew. This was advanced in the nineteenth century by Wilhelm de Wette and Friedrich Bleek.[11]

Markan priority began to be seriously proposed in the 18th century, was fleshed out during the 19th century, and became established scholarly fact by the 20th century, with the two-source hypothesis the most popular variant. By the 1960s, scholars considered the two-source hypothesis to be the unquestioned solution to the synoptic problem. William R. Farmer raised objections to it in his 1964 book The Synoptic Problem, but this view did not receive much uptake among scholars; exceptions included Bernard Orchard and David Laird Dungan.[12] At a conference in 1979, proponents agreed to change the name from "Griesbach hypothesis" to "two-gospel hypothesis".[13] Others such as David Alan Black have kept up support for the two-gospel hypothesis since.

Criticism

[edit]Many generic arguments in favor of Markan Priority and/or Two-source hypothesis also work as arguments against the two-gospel hypothesis. While it is impossible to list all arguments in favor and against the theory, some notable arguments are as follows.

- If Luke had access to the final version of Matthew (as opposed to both drawing independently on other sources), why are there so many significant differences between Luke and Matthew on issues such as Jesus' genealogy, circumstances of birth, and events following resurrection? While Luke and Matthew do share a lot of text which is not present in Mark, almost all of it is confined to teachings and parables. Construction of the gospels in accordance with the two-gospel hypothesis would require Luke to rewrite major parts of Matthew's narrative – even though Matthew was presumably an eyewitness who lived in Jerusalem and was surrounded by other eyewitnesses, and Luke was neither.

- "The argument from omission": why would Mark and Peter omit such remarkable and miraculous events as virgin birth of Jesus and particularly his appearance to apostles following resurrection? Both Matthew and Luke explicitly attest that Jesus appeared to the eleven disciples, including Peter, after his resurrection, and it seems incredible that Peter would not testify to that fact in his public speeches. And why is the Sermon on the Mount completely omitted from both Mark and Luke?[14]

- Proponents cite the simplicity of not having to include an unknown lost tradition in Q. However, lost sources are not unusual in antiquity, with thousands of references by surviving works to books that were not preserved. Even strictly theologically, lost works are attested to directly in scripture: an Epistle to the Laodiceans is referenced in Colossians, but is generally considered lost. The book of 2 Maccabees, a deuterocanonical book considered scripture in the Catholic and Orthodox traditions, directly states it is an abridgement of a five-volume work by Jason of Cyrene, but this original work has been lost. Even if taken on its own terms, the two-gospel hypothesis cites patristic evidence such as Papias who believed there to be a "Gospel of the Hebrews". If such a document existed, it too has since been lost.

- Proponents also cite the early Church Fathers as holding a position of Matthaean priority. However, the early Church Fathers disagreed with each other on many issues, and held various positions given credence by essentially no one today. The earliest reference to all four canonical gospels that calls them by the names ascribed to them now is from Irenaeus's Against Heresies (written around 185 AD) and the Muratorian fragment (written around 170–200 AD) - over a century after Jesus's death. Justin Martyr, writing 30 years earlier than Irenaeus from the same location (Rome), loosely quotes gospels but does not give them their modern attributions, suggesting that these attributions were made at some point between 150–180. If the stories of Mark recording Peter's speeches truly originated from Rome circa 60 AD, why did Justin not refer to Mark or Peter? Even if Justin simply omitted mention coincidentally, it is still a long time for a chain of oral transmission traditions on authorship before it is recorded. As such, the Church Fathers should not be assumed to have special insight into the truth on this matter.[15]

- Conversely, if the early Church Fathers really are reliable, then why not trust them on their ordering of Matthew - Mark - Luke? The two-gospel hypothesis introduces a delay in the dissemination of Luke to explain the traditional order, but such a delay is never described explicitly in ancient church writings.[16]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Robert L. Thomas (ed.), Three Views on the Origins of the Synoptic Gospels, Kregel Academic, p. 10.

- ^ Beck

- ^ Black

- ^ Black

- ^ Black

- ^ Beck

- ^ Black

- ^ Beck

- ^ Black

- ^ Orchard & Riley 1987, pp. 208–209.

- ^ Powers, B. Ward (2010). The Progressive Publication of Matthew: An Explanation of the Writing of the Synoptic Gospels. B&H Publishing. ISBN 978-0805448481.

- ^ Farmer, William R. (1964). The Synoptic Problem: A Critical Analysis. New York: Western North Carolina Press.

- ^ Neville, David. Mark's Gospel: Prior Or Posterior? A Reappraisal of the Phenomenon of Order

- ^ "The Priority of Mark".

- ^ Ehrman, Bart (2016). Jesus Before the Gospels. HarperCollins. p. 63–67. ISBN 9780062285232.

- ^ Ennulat, Andreas. Die "Minor Agreements". Untersuchungen zu einer offenen Frage des synoptischen Problems. J. C. B. Mohr, Tübingen 1994. p. 28.

Sources

[edit]For Griesbach's life and work, including the full text of the cited work in Latin and in English translation, cf. Bernard Orchard and Thomas R. W. Longstaff (ed.), J. J. Griesbach: Synoptic and Text-Critical Studies 1776–1976, Volume 34 in SNTS Monograph Series (Cambridge University Press, hardback 1978, paperback 2005 ISBN 0-521-02055-7).

- Beck, David (2001). Rethinking the Synoptic Problem. Baker Academic. ISBN 0-8010-2281-9.

- Black, David (2001). Why Four Gospels?. Kregel Publications. ISBN 0-8254-2070-9.

- Orchard, Bernard; Riley, Harold (1987). The Order of the Synoptics: Why Three Synoptic Gospels?. Mercer University Press.