Twisted Nerve

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2015) |

| Twisted Nerve | |

|---|---|

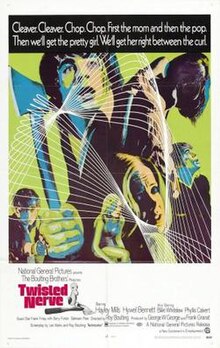

Foreign (U.S.) theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Roy Boulting |

| Screenplay by | Roy Boulting Leo Marks |

| Story by | Roger Marshall |

| Based on | idea by Marshall and Jeremy Scott |

| Produced by | Frank Granat George W. George executive John Boulting |

| Starring | Hayley Mills Hywel Bennett Billie Whitelaw Phyllis Calvert Frank Finlay |

| Cinematography | Harry Waxman |

| Edited by | Martin Charles |

| Music by | Bernard Herrmann |

Production company | Charter Film Productions |

| Distributed by | British Lion Films |

Release date |

|

Running time | 118 minutes[1] |

| Country | United Kingdom[2] |

Twisted Nerve is a 1968 British psychological thriller film directed by Roy Boulting and starring Hywel Bennett, Hayley Mills, Billie Whitelaw and Frank Finlay.[3][2] The film follows a disturbed young man, Martin, who pretends, under the name of Georgie, to be intellectually impaired in order to be near Susan, a girl with whom he has become infatuated. Martin kills those who get in his way.[4][5]

Plot

[edit]Martin plays catch with his older brother Pete, who has learning difficulties and has been sent to live in a special boarding school in London, by their mother. Martin is the only remaining figure in Pete's family life; their father died years before and their mother has a new life with her new husband, a wealthy banker. The school's physician believes that Pete cannot be expected to live much longer.

In a shop, Martin sees Susan purchase a toy. As she leaves, Martin follows after having pocketed a toy duck. Two store detectives ask them to return to the manager's office. The detectives assert that Martin and Susan were working together to steal the toy. Susan says she has never met Martin.

When questioned by the manager, Martin presents himself as mentally challenged, and calls himself "Georgie". Now disbelieving in a link between them, the manager asks Susan for her address, and Martin makes a mental note when she offers it. Sympathetic to him, Susan pays for Martin's toy.

Martin returns home and finds his parents arguing in the parlour, over his lack of interest in life, his unusual behaviour and the duck incident. In his room, now behaving as "Georgie", he rocks in a rocking chair while smiling in the mirror and caressing a stuffed animal. The rocking motion of the chair is smashing a photo of his stepfather.

The next day, Susan goes to the library, where she keeps an after-school job. Martin approaches Susan, who recognises him as Georgie. Martin says that he followed her, and pays her back for the toy. Before leaving, Martin gets Susan to lend him The Jungle Book.

Martin has a dispute with his stepfather, who insists he travel to Australia. Martin refuses and returns to his room. Martin stares in the mirror, bare-chested, and caresses himself. He then removes the rest of his clothes. There are male bodybuilding magazines on his dresser. A frustrated Martin eventually smashes the mirror.

Martin sets in motion a plan to leave home, pretending to go to France. He then shows up at Susan's mother's house, where she rents rooms. Presenting himself as Georgie, he gains sympathy both from Susan and her mother, who let him stay. Martin wants Susan to accept him as a lover, but cannot reveal that he is in fact Martin, as he is worried she will shun him.

One night, Martin steals scissors, leaves, and stabs his stepfather to death after the latter leaves a dinner party. The police investigate the murder and seek Martin for questioning.

Days later, Martin invites himself to tag along with Susan who is going for a swim at a country lake. There, Martin attempts to kiss Susan, who refuses his advances. Later at home, Susan searches Martin's room while cleaning and discovers books hidden in a drawer that a person with learning difficulties would not read or understand, as well as a book titled Know Yourself from Your Handwriting, in which signatures in the blank pages read 'Martin Durnley'.

Susan begins investigating Martin, talks with his mother, and realises that the two brothers are one and the same after seeing a photograph of Martin at the house. Susan visits her friend Shashee at a hospital where he works to question him about split personalities.

At Susan's house, Martin begins losing control over himself while suspecting that Susan may know who he really is. When Susan's neglected and unsuspecting mother attempts to sexually arouse Martin, he kills her with a hatchet.

When Susan arrives home, Martin holds her captive in his room after revealing his true persona. He forces Susan to undress so he can sexually fondle her, while her mother's body is found in the woodshed by Gerry Henderson, one of the "paying guests", who calls the police while Shashee learns the truth about Martin and races to the house to rescue Susan.

The police arrive and burst into Susan's room as Martin fires three times at his reflection in the mirror. While being taken away, he claims that he is Georgie and has killed Martin. Martin is confined in a cell at a mental hospital, ranting over his lost love Susan.

Cast

[edit]- Hywel Bennett as Martin Durnley / Georgie

- Hayley Mills as Susan Harper

- Billie Whitelaw as Joan Harper

- Phyllis Calvert as Enid Durnley

- Frank Finlay as Henry Durnley

- Barry Foster as Gerry Henderson

- Salmaan Peer as Shashee Kadir

- Christian Roberts as Philip Harvey

- Gretchen Franklin as Clarkie

- Thorley Walters as Sir John Forrester

- Timothy West as Superintendent Dakin

- Russell Napier as Professor Fuller

- Timothy Bateson as Mr. Groom

- Richard Davies as Taffy Evans

- Basil Dignam as doctor

- Robin Parkinson as shop manager

- Marianne Stone as store detective 1

- John Harvey as store detective 2

- Mollie Maureen as lady patient

- Brian Peck as Det. Sgt. Rogers

Production notes

[edit]In October 1967 John Boulting announced he would be making a film with Hayley Mills and Hywell Bennett who had just done The Family Way with the Boultings. They said a title had not been given to the film.[6]

The film was produced by George W. George and Frank Granat, who had just made Pretty Polly with Hayley Mills. Filming began on 2 January 1968.[7]

The film was a co-production between British Lion Films and a new American company, National General Pictures.[8]

Title

[edit]The title comes from the poem Slaves by George Sylvester Viereck (1884–1962) which is quoted twice in the movie, once during Professor Fuller's lecture on chromosome damage, and then as an audio flashback when Martin/Georgie is in a cell:

- No puppet master pulls the strings on high

- Proportioning our parts, the tinsel and the paint

- A twisted nerve, a ganglion gone awry,

- Predestinates the sinner and the saint.[9]

Viereck's motives for his writing have been the subject of some discussion, and have further implications given the debate on eugenics during the middle of the 20th century, a subject somewhat alluded to in Professor Fuller's lecture in the film.[10]

Soundtrack

[edit]The film score was composed by Bernard Herrmann and features an eerie whistling tune.[11][12]

The theme can also be heard in Quentin Tarantino's Kill Bill when a menacing Elle Driver (Daryl Hannah) impersonates a nurse in the hospital scene and in Death Proof as Rosario Dawson's character's ringtone, in several episodes of American Horror Story (2011–2021), in the Malayalam language Indian movie Chappa Kurishu as a ringtone of Fahad Fazil's character's iPhone, and in the Bengali movie Chotushkone where it is also used as a ringtone for Parambrata Chatterjee's character's phone. More recently, it has also been used in Honda's 2015 car advertisement.[13]

Stylotone Records reissued the score as part of a deluxe LP set, with a release date of 5 May 2016.[14]

The theme was also sampled in the Rob $tone songs, "Chill Bill", the Grooveman Jones song "The Hidden Interest", the Ava Max song “Get Outta My Heart” and the Lumidee song “Don't Sweat That”.

Release

[edit]Controversy

[edit]The film is notorious for its use of Down syndrome, then referred to as mongolism, as a catalyst for Martin's actions. Letters of complaint were sent to the British censor before the film's release, including one from the National Association for Mental Health. The film's medical adviser, Professor Lionel Penrose, asked for his name to be removed from the film. Roy Boulting said these complaints caused him "shock and surprise and a deep sense of regret and depression".[15] This led to the filmmakers adding a voiceover just prior to the credits which said:

In view of the controversy already aroused, the producers of this film wish to re-emphasise what is already stated in the film, that there is no established scientific connection between mongolism and psychotic or criminal behaviour.[16]

Even after that had been added, David Ennals, then a Minister of State, Health and Social Security, said: "I do not wish to criticise the film as a film. But I feel it is extremely unfortunate that despite the spoken disclaimer which precedes it, this film can give the impression that there is such a link."[17]

As The New York Times put it, "this is a delicate area indeed", going on to describe the film as "more unsettling than rewarding, and certainly more contrived than compassionate".[18]

Critical reception

[edit]The Monthly Film Bulletin wrote: "Small wonder that the makers of Twisted Nerve found it necessary to appease outraged medical opinion by adding an introduction to the film disclaiming any implied connection between mongolism and psychotic behaviour. The Boultings may have set out to make a serious comment on the plight of the mentally disordered, but what they have produced is a crudely sensationalist thriller decked out with some pseudoscientific jargon which suggests, intentionally or not, that the siblings of mongoloid children are likely to end up as homicidal maniacs. Any claim to seriousness is unequivocally nullified by Roy Boulting's bludgeoning approach to his already distasteful material ... But even viewed as a straightforward thriller, the film is so clumsily and predictably put together (witness the rash of timely coincidences in the climactic sequence) that the insurance company which has offered to pay out to the dependents of anyone dying of shock while watching it is hardly likely to find any clients. Billie Whitelaw (as the landlady) and Barry Foster (as a seedy film salesman decrying the trend towards sex and violence in the cinema, no less) apart, the performances are unremarkable: Hywel Bennett is baby-faced enough to make his childlike persona moderately convincing but can't manage the rest; and Hayley Mills shuffles through it all on a high-pitched monotone trying hard to look adult and concerned."[19]

The Guardian called the film "gross, clumsy and ridiculously predictable."[20]

The Observer called it "a glossy commercial psycho thriller which if it weren't for its pernicious implications would be perfectly horrifying" arguing the film would have been better had the character of the elder brother never existed. "Twisted Nerve is a fairly good blood chiller in its genre so long as it is clearly understood that it is a pack of lies."[21]

The Los Angeles Times called it "thoroughly engrossing, spine tingling."[22]

Filmink called it "not a very good movie in which Mills doesn’t have much to do except react – I think Boulting was trying to fashion her as a Hitchcock blonde but she’s very passive and the movie lacks the directorial flair of a Hitchcock, Seth Holt or Freddie Francis."[23]

References

[edit]- ^ "TWISTED NERVE (X)". British Board of Film Classification. 16 October 1968. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- ^ a b "Twisted Nerve (1968)". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 10 March 2016.

- ^ "Twisted Nerve". British Film Institute. Retrieved 18 August 2024.

- ^ "Twisted Nerve (1968) – Roy Boulting – Review – AllMovie". AllMovie.

- ^ TWISTED NERVE, Monthly Film Bulletin; London Vol. 36, Iss. 420, (1 Jan 1969): 29.

- ^ Where does British Lion go from here?, BOULTING, JOHN. The Guardian 4 October 1967: 14.

- ^ MOVIE CALL SHEET: Joanne Dalsass to Debut, Martin, Betty. Los Angeles Times 26 December 1967: e25.

- ^ Capote's 'Prayers' Are Answered, By A. H. WEILER. The New York Times 18 February 1968: 99.

- ^ The poem was published in Viereck, George Sylvester (1924). The Three Sphinxes and Other Poems. Girard, Kansas: Haldeman Julius Co. The poem is reproduced in full in Abel, Reuben (2010). Man is the Measure. Simon and Schuster. p. 203. ISBN 9781439118405.

- ^ Toth, George (18 November 2010). "George Viereck: Diplomat or Propagandist?". The University of Iowa Libraries, Special Collections and University Archives. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- ^ "Bernard Herrmann". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 13 February 2016.

- ^ Thomas, Kevin (4 February 1968). "Film Composer Settles a Score". Los Angeles Times. p. D-16.

- ^ Favourites Anonymous. Sight & Sound; London Vol. 14, Iss. 9, (Sep 2004): 32–36, 38–40.

- ^ Ediriwira, Amar (4 March 2016). "Bernard Hermann reissues launch new soundtrack label". TheVinylFactory.com. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- ^ 'Boulting film is deplored' Shearer, Ann. The Guardian 4 December 1968: 1.

- ^ Boulting film announcement, The Guardian 6 December 1968: 7.

- ^ 'Mr Ennals joins critics', Our own Reporter. The Guardian 7 December 1968: 1

- ^ "Movie Review – 'Twisted Nerve' Opens at 2 Houses – NYTimes.com". The New York Times. 15 September 2022.

- ^ "Twisted Nerve". The Monthly Film Bulletin. 36 (420): 29. 1 January 1969 – via ProQuest.

- ^ Twisted by whom?, Roud, Richard. The Guardian 4 December 1968: 6.

- ^ Hitting the headlines Mortimer, Penelope. The Observer 8 December 1968: 26.

- ^ Thomas, Kevin (16 April 1969). "Movie Review: 'Nerve' Opens at Beverley Hills". Los Angeles Times. pp. IV-10 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Vagg, Stephen (19 March 2022). "Movie Star Cold Streaks: Hayley Mills". Filmink.

External links

[edit]- Twisted Nerve at IMDb

- Review of film at Variety

- Twisted Nerve at Letterbox DVD

- 1968 films

- 1968 horror films

- 1968 independent films

- 1960s psychological thriller films

- 1960s slasher films

- British horror thriller films

- British independent films

- British slasher films

- Down syndrome in film

- British Lion Films films

- 1960s English-language films

- Films scored by Bernard Herrmann

- Films directed by Roy Boulting

- Films set in London

- Films shot in England

- Films shot in Surrey

- British serial killer films

- 1960s British films

- English-language independent films

- English-language horror thriller films