Tartessos

Tartessos (Spanish: Tartesos) is, as defined by archaeological discoveries,[1] a historical civilization settled in the southern Iberian Peninsula characterized by its mixture of local Paleohispanic and Phoenician traits. It had a writing system, identified as Tartessian, that includes some 97 inscriptions in a Tartessian language.

In the historical records, Tartessos (Ancient Greek: Ταρτησσός) appears as a semi-mythical or legendary harbor city and the surrounding culture on the south coast of the Iberian Peninsula (in modern Andalusia, Spain), at the mouth of the Guadalquivir.[2] It appears in sources from Greece and the Near East starting during the first millennium BC. Herodotus, for example, describes it as beyond the Pillars of Hercules.[3] Roman authors tend to echo the earlier Greek sources, but from around the end of the millennium there are indications that the name Tartessos had fallen out of use and the city may have been lost to flooding, although several authors attempt to identify it with cities of other names in the area.[4]

The Tartessians were rich in metals. In the fourth century BC the historian Ephorus describes "a very prosperous market called Tartessos, with much tin carried by river, as well as gold and copper from Celtic lands".[4] Trade in tin was very lucrative in the Bronze Age, since it is an essential component of bronze and is comparatively rare. Herodotus refers to a king of Tartessos, Arganthonios, presumably named for his wealth in silver. Herodotus also says that Arganthonios welcomed the first Greeks to reach Iberia, which was a ship carrying the Phocaeans from Asia Minor.

Pausanias wrote that Myron, the tyrant of Sicyon, built a treasury, which was called the treasury of the Sicyonians, to commemorate a victory in the chariot race at the Olympic games. In the treasury, he made two chambers with two different styles, one Doric and one Ionic, with bronze.[clarification needed] The Eleans said that the bronze was Tartessian.[5][6]

The people from Tartessos became important trading partners of the Phoenicians, whose presence in Iberia dates from the eighth century BC and who nearby built a harbor of their own, Gadir (Ancient Greek: Γάδειρα, Latin: Gades, present-day Cádiz).

Location

[edit]

Several early sources, such as Aristotle, refer to Tartessos as a river. Aristotle claims that it rises from the Pyrene Mountain (generally accepted by modern scholars as the Pyrenees) and flows out to sea outside the Pillars of Hercules, the modern Strait of Gibraltar.[4] No such river traverses the Iberian Peninsula.

According to the fourth century BC Greek geographer and explorer Pytheas, quoted by Strabo in the first century AD, the ancestral homeland of the Turduli was located north of Turdetania, the region where the kingdom of Tartessos was located in the Baetis River valley (the present-day Guadalquivir valley) in southern Spain.[7][8]

Pausanias, writing in the second century AD, identified the river and gave details of the location of the city:

They say that Tartessus is a river in the land of the Iberians, running down into the sea by two mouths and that between these two mouths lies a city of the same name. The river, which is the largest in Iberia and tidal, those of a later day called Baetis and there are some who think that Tartessus was the ancient name of Carpia, a city of the Iberians.[9]

The river known in his day as the Baetis is now the Guadalquivir. Thus, Tartessos may be buried, Schulten thought, under the shifting wetlands. The river delta has gradually been blocked by a sandbar that stretches from the mouth of the Rio Tinto, near Palos de la Frontera to Almonte, the riverbank that is opposite Sanlúcar de Barrameda. The area is now protected as the Parque Nacional de Doñana.[10]

In the first century AD, Pliny the Elder[11] incorrectly identified the city of Carteia as the Tartessos mentioned in Greek sources while Strabo just commented.[clarification needed] [12] Carteia is identified as El Rocadillo, near S. Roque, Province of Cádiz, some distance away from the Guadalquivir.[13] In the second century AD, Appian thought that Karpessos (Carpia) was previously known as Tartessos.[4]

Archaeological discoveries

[edit]The discoveries published by Adolf Schulten in 1922 [14] first drew attention to Tartessos and shifted its study from classical philologists and antiquarians to investigations based on archaeology,[15] although attempts at localizing a capital for what was conceived as a complicated culture in the nature of a centrally controlled kingdom ancestral to Spain were inconclusively debated. Subsequent discoveries were widely reported: in September 1923 archaeologists discovered a Phoenician necropolis in which human remains were unearthed and stones found with illegible characters. It may have been colonized by the Phoenicians for trade because of its richness in metals.[16]

A later generation turned instead to identifying and localizing "orientalizing" (eastern Mediterranean) features of the Tartessian material culture within the broader Mediterranean horizon of an "Orientalizing period" recognizable in the Aegean and Etruria.

J. M. Luzón was the first to identify Tartessos with modern Huelva,[17] based on discoveries made in the preceding decades. Since the discovery in September 1958 of the rich gold treasure of El Carambolo in Camas, three kilometres west of Seville,[18] and of hundreds of artefacts in the necropolis at La Joya, Huelva,[19] archaeological surveys have been integrated with philological and literary surveys and the broader picture of the Iron Age in the Mediterranean basin to provide a more informed view of the supposed Tartessian culture on the ground, concentrated in western Andalusia, Extremadura, and in southern Portugal from the Algarve to the Vinalopó River in Alicante.[20]

Turuñuelo archaeological site

[edit]

Significant discoveries were made at Turuñuelo archeological site in Guareña, where excavation began in 2015. The site was declared bien de interés cultural (National heritage site) in May 2022.[21][22]

Two ornate stone busts, featuring details of jewelry and hairstyles which are thought to be the first facial representations of the Tartessian goddesses were discovered in 2023.[23][24] These sculptures are somewhat similar to the Lady of Elche sculpture, which was dated between the 5th and 4th centuries BC, but are considerably earlier. Fragments of at least three other busts have also been recovered. One of them is attributed to a warrior because part of his helmet is preserved.

In this region of southern Spain, the Tartessian culture was born around the 9th century B.C. as a result of hybridization between the Phoenician settlers and the local inhabitants. Scholars refer to the Tartessian culture as "a hybrid archaeological culture".[25]

Metallurgy

[edit]Alluvial tin was panned in Tartessian streams from an early date. The spread of a silver standard in Assyria increased its attractiveness (the tribute from Phoenician cities was assessed in silver). The invention of coinage in the seventh century BC spurred the search for bronze and silver as well. Henceforth trade connections, formerly largely in elite goods, assumed an increasingly broad economic role. By the Late Bronze Age, silver extraction in Huelva Province reached industrial proportions. Pre-Roman silver slag is found in the Tartessian cities of Huelva Province. Cypriot and Phoenician metalworkers produced 15 million tons of pyrometallurgical residues at the vast dumps of Riotinto. Mining and smelting preceded the arrival, from the eighth century BC onward, of Phoenicians [26] and then Greeks, who provided a stimulating wider market and whose influence sparked an "orientalizing" phase in Tartessian material culture (c. 750–550 BC) before Tartessian culture was superseded by the Classic Iberian culture.

"Tartessic" artefacts linked with the Tartessos culture have been found, and many archaeologists now associate the "lost" city with Huelva. In excavations on spatially restricted sites in the center of modern Huelva, sherds of elite painted Greek ceramics of the first half of the sixth century BC have been recovered. Huelva contains the largest accumulation of imported elite goods and must have been an important Tartessian center. Medellín, on the Guadiana River, revealed an important necropolis.

Elements specific to Tartessian culture are the Late Bronze Age fully evolved pattern-burnished wares and geometrically banded and patterns "Carambolo" wares, from the ninth to the sixth centuries BC; an "Early Orientalizing" phase with the first eastern Mediterranean imports, beginning circa 750 BC; a "Late Orientalizing" phase with the finest bronze casting and goldsmith work; gray ware turned on the fast potter's wheel, local imitations of imported Phoenician red-slip wares.

Characteristic Tartessian bronzes include pear-shaped jugs, often associated in burials, with shallow dish-shaped braziers having loop handles, incense-burners with floral motifs, fibulas, both elbowed and double-spring types, and belt buckles.

No pre-colonial necropolis sites have been identified. The change from a late Bronze Age pattern of circular or oval huts scattered on a village site to rectangular houses with dry-stone foundations and plastered wattle and daub walls took place during the seventh and sixth centuries BC, in settlements with planned layouts that succeeded one another on the same site.

At Cástulo (Jaén), a mosaic of river pebbles from the end of the sixth century BC is the earliest mosaic in Western Europe.[citation needed] Most sites were inexplicably abandoned in the fifth century BC.

Tartessic occupation sites of the Late Bronze Age that were not particularly complex: "a domestic mode of production seems to have predominated" is one mainstream assessment.[27] An earlier generation of archaeologists and historians took a normative approach to the primitive Tartessian adoption of Punic styles and techniques, as of a less-developed culture adopting better, more highly evolved cultural traits, and finding Eastern parallels for Early Iron Age material culture in the Tartessian sites. A later generation has been more concerned with the process through which local institutions evolved.[28]

The emergence of new archaeological finds in the city of Huelva is prompting the revision of these traditional views. Just in two adjacent lots adding up to 2,150 sq. m. between Las Monjas Square and Mendez Nuñez Street, some 90,000 ceramic fragments of indigenous, Phoenician, and Greek imported wares were exhumed, out of which 8,009 allowed scope for a type identification. This pottery, dated from the tenth to the early eighth centuries BC predates finds from other Phoenician colonies; together with remnants of numerous activities, the Huelva discoveries reveal a substantial industrial and commercial emporion on this site lasting several centuries. Similar finds in other parts of the city make it possible to estimate the protohistoric habitat of Huelva at some 20 hectares, large for a site in the Iberian Peninsula during that period.[29]

Calibrated carbon-14 dating carried out by University of Groningen on associated cattle bones as well as dating based on ceramic samples permit a chronology of several centuries through the state of the art of craft and industry since the tenth century BC, as follows: pottery (bowls, plates, craters, vases, amphorae, etc.), melting pots, casting nozzles, weights, finely worked pieces of wood, ship parts, bovid skulls, pendants, fibulae, anklebones, agate, ivory –with the only workshop of the period so far proven in the west-, gold, silver, etc.

The existence of foreign produce and materials together with local ones suggests that the old Huelva harbor was a major hub for the reception, manufacturing, and shipping of diverse products of different and distant origin. The analysis of written sources and the products exhumed, including inscriptions and thousands of Greek ceramics, some of which are works of excellent quality by known potters and painters, has led some scholars to suggest that this habitat can be identified not only with Tarshish mentioned in the Bible, in the Assyrian stele of Esarhaddon, and perhaps in the Phoenician inscription of the Nora Stone, but also with the Tartessos of Greek sources –interpreting the Tartessus river as equivalent to the present-day Tinto River and the Ligustine Lake to the joint estuary of the Odiel and Tinto rivers flowing west and east of the Huelva Peninsula.[30][31][32]

Religion

[edit]There is very little data but it is assumed that as with other Mediterranean peoples, the religion was polytheistic. It is believed that Tartessians worshiped the goddess Astarte or Potnia and the masculine divinity Baal or Melkart, as a result of the Phoenician acculturation. Sanctuaries inspired by Phoenician architecture have been found in the deposit of Castulo (Linares, Jaén) and in the vicinity of Carmona. Several images of Phoenician deities have been found in Cádiz, Huelva, and Sevilla.[33]

Language

[edit]

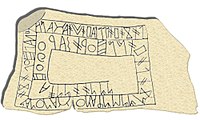

The Tartessian language is an extinct pre-Roman language once spoken in southern Iberia. The oldest known indigenous texts of Iberia, dated from the seventh to sixth centuries BC, are written in Tartessian. The inscriptions are written in a semi-syllabic writing system called the Southwest script; they were found in the general area in which Tartessos was located and in surrounding areas of influence. Tartessian language texts were found in Southwestern Spain and Southern Portugal (namely in the Conii, Cempsi, Sefes, and Celtici areas of the Algarve and southern Alentejo).

Possible identification as "Tarshish" or "Atlantis"

[edit]Since the classicists of the early twentieth century, biblical archaeologists often identify the place-name Tarshish in the Hebrew Bible with Tartessos, although others connect Tarshish to Tarsus in Anatolia or other places as far as India. Tarshish, like Tartessos, is associated with extensive mineral wealth (Iberian Pyrite Belt).

In 1922, Adolf Schulten gave currency to a view of Tartessos that made it the Western, and wholly European source of the legend of Atlantis.[34] A more serious review, by W. A. Oldfather, appeared in American Journal of Philology.[35] Both Atlantis and Tartessos were believed to have been advanced societies that collapsed when their cities were lost beneath the waves; supposed further similarities with the legendary society make a connection seem feasible, although virtually nothing is known of Tartessos, not even its precise site. Other Tartessian enthusiasts imagine it as a contemporary of Atlantis, with which it might have traded.[citation needed]

In 2011, a team led by Richard Freund claimed to have found strong evidence for the location in Doñana National Park based on underground and underwater surveys and the interpretation of the archaeological site Cancho Roano[36] as "memorial cities" rebuilt in the image of Atlantis. [37] Spanish scientists have dismissed Freund's claims claiming that he was sensationalising their work. The anthropologist Juan Villarías-Robles, who works with the Spanish National Research Council, said "Richard Freund was a newcomer to our project and appeared to be involved in his own very controversial issue concerning King Solomon's search for ivory and gold in Tartessos, the well-documented settlement in the Doñana area established in the first millennium BC" and described his claims as 'fanciful'.[38]

Simcha Jacobovici, involved in the production of a documentary on Freund's work for the National Geographic Channel, stated that the biblical Tarshish (which he believes is the same as Tartessos) was Atlantis, and that "Atlantis was hiding in the Tanach", although this is heavily disputed by most archeologists involved in the project. The enigmatic Lady of Elx, an ancient bust of a woman found in southeastern Spain, has been tied with Atlantis and Tartessos,[citation needed] although the statue displays clear signs of being manufactured by later Iberian cultures.

See also

[edit]- Colaeus

- Atlantic Bronze Age

- South-Western Iberian Bronze

- Prehistoric Iberia

- Spanish mythology

- Turdetani

- Turduli

- Pre-Roman peoples of the Iberian Peninsula

- Cancho Roano

References

[edit]- ^ Construyendo Tarteso

- ^ Brandherm, Dirk (1 September 2016). "6: Stelae, Funerary Practice, and Group Identities in the Bronze and Iron Ages of SW Iberia: A Moyenne Durée Perspective". In Koch, John T.; Barry Cunliffe (eds.). Celtic from the West 3, Atlantic Europe in the Metal Ages: questions of shared language. Oxbow Books. p. 179. ISBN 978-1-78570-230-3.

- ^ Herodotus, The History, i. 163; iv.152.

- ^ a b c d Freeman, Phillip M. (2010). "Ancient references to Tartessos", chapter 10. IN: Cunliffe, Barry and John T. Koch (eds.), Celtic from the West: Alternative Perspectives From Archaeology, Genetics, Language And Literature.

- ^ Pausanias, Description of Greece, 6.19.1

- ^ Pausanias, Description of Greece, 6.19.2

- ^ Freeman, Phillip M. (2010). Celtic from the West Chapter 10 - Ancillary Study: Ancient References to Tartessos. Oxbow Books, Oxford, UK. p. 322. ISBN 978-1-84217-410-4.

- ^ Strabo. Geography. pp. Book III Chapter 2 verse 11.

- ^ Pausanias Description of Greece 6.XIX.3.

- ^ Thirty kilometers inland there still is a mining town by the name of Tarsis.

- ^ Pliny, Natural History, 3.7.

- ^ Strabo. Geography. pp. Book III Chapter 2 verse 14.

- ^ Talbert, Richard J. A. (ed.). Map-by-Map Directory to Accompany the Barrington Atlas of The Greek and Roman World (2000), p. 419. Archived 2011-07-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Schulten (1922). Tartessos. Hamburg; Spanish tr. Madrid, 1924, 2nd ed. 1945).

- ^ The historiography of Tartessos is surveyed by Carlos G. Wagner, "Tartessos en la historiografía: un revisión crítica".

- ^ "Dig Up Phoenician City", New York Times, September 26, 1923, p. 3.

- ^ Luzón, J. M. (1962). "Tartessos y la ría de Huelva". Zephyrus. 13: 97–104.

- ^ Carriazo, J. M. El tesoro y las primeras excavaciones en 'El Carambolo' (Camas, Sevilla) (Excavaciones Arqueológicas en España), 1970.

- ^ Garrido, J. P. (1970). Excavaciones en la necrópolis de La Joya, E.A.E.

- ^ The results of Tartessian archaeology as of 1987 were summarized by Chamorro, Javier G. (1987). "Survey of Archaeological Research on Tartessos". American Journal of Archaeology. 91 (2): 197–232. doi:10.2307/505217. JSTOR 505217. S2CID 191378720.

- ^ "Meritxell Batet destaca el yacimiento tartésico de 'El Turuñuelo' en Guareña y la "colaboración entre administraciones"". Europa Press. 17 September 2022.

- ^ Macías, C. (12 July 2021). "El Turuñuelo: la misteriosa escalera extremeña que podría cambiar todos los manuales". El Confidencial.

- ^ "Archaeologists uncover the first human representations of the ancient Tartessos people". HeritageDaily - Archaeology News. 19 April 2023. Retrieved 2023-04-24.

- ^ Altuntaş, Leman (2023-04-19). "Archaeologists have uncovered the first human representations of the people of mythical Tartessos". Arkeonews. Retrieved 2023-04-24.

- ^ Carolina López-Ruiz, Michael Dietler 2009 (eds), Colonial Encounters in Ancient Iberia: Phoenician, Greek, and Indigenous Relations. University of Chicago Press. p.194

- ^ Phoenician coastal settlements and necropoli are typically located at the mouth of rivers, on the first hill behind the delta, at Cadiz, Málaga, Granada, and Almeria.

- ^ Wagner, in Alvar and Blásquez 1991:104.

- ^ Essays from both points of view are found in Alvar and Blázquez, according to the review by Antonio Gilman in American Journal of Archaeology 98.2 (April 1994), pp. 369-370.

- ^ Detailed description and analysis of the objects found and sources mentioned above are surveyed in Fernando González de Canales Cerisola, Del Occidente Mítico Griego a Tarsis-Tarteso –Fuentes escritas y documentación arqueológica (2004) and F. González de Canales, L. Serrano and J. Llompart, El Emporio Fenicio-Precolonial de Huelva, ca. 900-770 a.C. (2004).

- ^ (es) Gonzalez de Canales Cerisola, F. Del Occidente Mítico Griego a Tarsis-Tarteso –Fuentes escritas y documentación arqueológica, Madrid, Biblioteca Nueva, 2004

- ^ (es) Gonzalez de Canales, F.; J. Llompart and L. Serrano. El Emporio Fenicio-Precolonial de Huelva, ca. 900-770 a.C.. Madrid, Biblioteca Nueva, 2004

- ^ Gonzalez de Canales Cerisola, F. (2014). "Tarshish-Tartessos, the Emporium Reached by Kolaios of Samos". Cahiers de l'Institut du Proche-Orient Ancien du Collège de France (CIPOA) II. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

- ^ "RELIGIÓN TARTÉSSICA". Archived from the original on 2016-02-21. Retrieved 2016-02-27.

- ^ Schulten, A. (1923). Ein Beitrage zur ältestens Geschichte des Westens (Hamburg 1922). An amused reviewer for The Journal of Hellenic Studies (43. 2, p. 206) agreed that "we are quite willing to add it to the long list of possible origins for the Atlantis legend" and that "our hearts burn within us to think of the Tartessian literature six thousand years old".

- ^ The American Journal of Philology, 44.4 (1923), pp. 368-371.

- ^ "Finding Atlantis". National Geographic Channel. Archived from the original on 7 July 2011. Retrieved 2 December 2014.

- ^ Canadians part of search for fabled city of Atlantis. In: Montreal Gazette, 3/13/11 [1][permanent dead link]

- ^ Owen, Edward (14 March 2011). "Lost city of Atlantis 'buried in Spanish wetlands'". The Telegraph. London. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

Sources

[edit]- Blazquez, J. M. A. (1968). Tartessos y Los Origenes de la Colonizacion Fenicia en Occidente. University of Salamanca. Assemblies of Punic materials found in Spain.

- Alvar, Jaime; José María Blázquez (1993). Los enigmas de Tartessos. Madrid: Catedra. Papers following a 1991 conference.

- Chocomeli, J. (1940). En busca de Tartessos, Valencia.

- Gonzalez de Canales Cerisola, F. (2004). Del Occidente Mítico Griego a Tarsis-Tarteso –Fuentes escritas y documentación arqueológica-, Biblioteca Nueva, Madrid.

- Gonzalez de Canales, F.; J. Llompart and L. Serrano (2004). El Emporio Fenicio-Precolonial de Huelva, ca. 900-770 a.C., Biblioteca Nueva, Madrid.

- Celestino S.; C. López-Ruiz (2016). Tartessos and the Phoenicians in Iberia, Oxford University Press, New York.

External links

[edit]General

[edit]- Almagro-Gorbea. "La literatura tartésica fuentes históricas e iconográficas"

- Detailed map of the Pre-Roman Peoples of Iberia (circa 200 BC)

- Doñana

- Spaniards search for legendary Tartessos in a marsh

- Jewish Encyclopedia: Tarshish, a distant maritime district famed for its metalwork, considered by the contributors in 1901-1906 to be legendary; Old Testament references.

- Júdice Gamito, Teresa (e-Keltoi 6) The Celts in Portugal

- Tartessos in The Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites