The Tree of Life (film)

| The Tree of Life | |

|---|---|

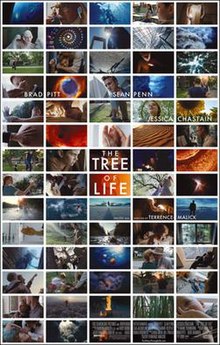

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Terrence Malick |

| Written by | Terrence Malick |

| Produced by | |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Emmanuel Lubezki |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by | Alexandre Desplat |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by |

|

Release dates |

|

Running time |

|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $32 million[3] |

| Box office | $61.7 million[4] |

The Tree of Life is a 2011 American epic experimental coming-of-age drama film written and directed by Terrence Malick. Its main cast includes Brad Pitt, Sean Penn, Hunter McCracken, Laramie Eppler, Jessica Chastain, and Tye Sheridan in his debut feature film role. The film chronicles the origins and meaning of life by way of a middle-aged man's childhood memories of his family living in 1950s Texas, interspersed with imagery of the origins of the universe and the inception of life on Earth.

After several years in development and missing its planned 2009 and 2010 release dates, The Tree of Life premiered in competition at the 2011 Cannes Film Festival,[5] where it was awarded the Palme d'Or. It ranked number one on review aggregator Metacritic's "Film Critic Top Ten List of 2011",[6] and made more critics' year-end lists for 2011 than any other film.[7] It has since been ranked by some publications as one of the greatest films of the 2010s,[8] of the 21st century,[9] and of all time.[10] The Tree of Life received three Oscar nominations: Best Picture, Best Director and Best Cinematography.

Plot

[edit]Premise

[edit]The film follows the members of the O'Brien family in the 1940s-1960s[11] and 2010. Most of the film takes place in the 1950s,[12] but the film jumps between different narratives. The O'Briens appear to be a standard American middle-class suburban family. Mr. O'Brien is a successful engineer for an energy company, but has enough free time to indulge his love of music. Mrs. O'Brien is a housewife with many friends in the neighborhood. They have three healthy boys, Jack, R.L., and Stevie. However, the film reveals deep cracks behind the facade, which leave Jack traumatized for decades.

Theatrical Edition

[edit]"Where were you when I laid the foundations of the Earth? ... When the morning stars sang together, and all the sons of God shouted for joy?"

In the 1960s, Mrs. and Mr. O'Brien are devastated to learn that their son R.L., aged 19, has died. In 2010, Jack is a successful but world-weary architect in an unnamed city.[a] He leads a seemingly empty existence and has a difficult relationship with his elderly father, who still has not gotten over R.L.'s death. In voiceover, Mrs. O'Brien asks God why R.L. had to die. Then, a series of dreamlike visuals depict the birth of the universe, the creation, of Earth and the beginning of life. At one point, a dinosaur spares another, badly wounded, dinosaur. Finally, an asteroid strikes the Earth.

In the 1940s, Mrs. and Mr. O'Brien start a family in the Waco suburbs. They have very different personalities. Jack's mother teaches him that mankind is divided into the "way of nature" and the "way of grace"—a view analogous to, but not precisely, complementarianism. Jack sees his mother as the embodiment of grace: kind, forgiving, and nurturing. She presents the world to her sons as a place of wonder. Jack sees his father as the embodiment of nature: hot-tempered, tough, and stern. He teaches his sons to fight and to not trust people easily.

As Jack grows older, he learns that his parents are frustrated with their lives. Mr. O'Brien finds his career unfulfilling, as his true passion is music. He spends his free time inventing gadgets and hopes to start his own business. One of the inventions looks promising, but after Mr. O'Brien loses a patent suit, nothing changes. Mrs. O'Brien lives under the thumb of her domineering husband, who screams at her and blames her for not disciplining the boys enough. He worries that her kindness, which contrasts with his discipline, has caused his sons to hate him.

As a teenager, Jack begins to question his parents' philosophy of life. The death of his friend Taylor shakes his faith in the goodness of God. He resents his father, who harshly disciplines him but cuts R.L. slack because of their shared love of music. He criticizes his mother for failing to stand up to his father. When Mr. O'Brien goes on a business trip, a weight is lifted from the family's shoulders. The boys happily play with their mother. However, without his father's discipline, Jack's rebellious streak emerges. Peer-pressured, Jack commits vandalism and animal abuse, and steals a nightgown from his crush's house.

Mr. O'Brien's plant shuts down, forcing the family to relocate. Before leaving the house for the last time, Mr. O'Brien has a moment of self-reflection. He asks Jack to forgive him for his harshness, and tries to conciliate Jack by telling him that he takes after his mother. However, Jack insists that he better resembles his father.

Returning to 2010, Jack has a vision of a young girl, accompanied by himself as a child, walking across desolate terrain. He walks through a wooden door frame and sees a view of the far distant future in which the Sun expands into a red giant, engulfing Earth and then shrinking into a white dwarf. The dead return to life and gather at the seaside, where Jack is reunited with his family and all those who populate his memory. Jack meets his brothers and brings R.L. to his parents, who embrace him as a long-lost son. Accompanied by two girls in white, Mrs. O'Brien gracefully whispers, "I give him to you. I give you my son."

Jack's vision ends and he leaves his office, smiling contentedly. The mysterious light continues flickering in the darkness.

Extended Edition

[edit]Malick released an extended version of the film in September 2018, which incorporates unused footage from the original film shoot. Although Malick maintains that the theatrical edition is the official director's cut,[14] the extended version expands on the character of Mr. O'Brien and broadly questions Mrs. O'Brien's either-or distinction between nature and grace.

Additional plot elements include:[14][15][16][17][18]

- In the present day, the film fills in details of Jack's life as he wanders around Dallas. Although he cheats on his wife, he tries to look after his teenage son.

- Mrs. O'Brien once aspired to be a scientist, but gave it up to be a housewife.

- Mr. O'Brien is haunted by his memories of his own father, a Navy veteran who was unsuccessful in civilian life. Terrified of ending up like his father, he pushes himself to make it big in business.

- Mr. O'Brien spends more time playing with his sons and teaching them to love music like he does.

- Mrs. O'Brien's brother Ray visits the family. Although Ray, like Mr. O'Brien, has a masculine demeanor, he does not fit into the "way of nature" paradigm, and harshly criticizes Mr. O'Brien for mistreating his nephews. Mr. O'Brien is jealous of how much his sons like Ray, and criticizes Ray for his unsuccessful career.

- Jack visits a friend's house and sees that the O'Briens are not the only family in Waco with domestic tensions.

- Jack's increasing rebelliousness leads him to become an inattentive student. As Jack declines academically, Mr. O'Brien realizes his own deficiencies as a father. To give Jack another chance in a better environment, he sends Jack to boarding school. One of the final scenes shows Jack exploring the campus of Malick's alma mater, St. Stephen's Episcopal School in Austin.

Cast

[edit]- Brad Pitt as Mr. O'Brien

- Jessica Chastain as Mrs. O'Brien

- Sean Penn as Jack O'Brien

- Hunter McCracken as young Jack

- Finnegan Williams as Jack (age 5)

- Michael Koeth as Jack (age 2)

- Laramie Eppler as R.L. O'Brien

- John Howell as R.L. (age 2)

- Tye Sheridan as Steve O'Brien

- Kari Matchett as Jack's ex

- Joanna Going as Jack's wife

- Michael Showers as Mr. Brown

- Kimberly Whalen as Mrs. Brown

- Jackson Hurst as Uncle Ray

- Fiona Shaw as Grandmother

- Crystal Mantecón as Elisa

- Tamara Jolaine as Mrs. Stone

- Dustin Allen as George Walsh

- Tommy Hollis as Tommy

Production

[edit]Development

[edit]In the late 1970s, Terrence Malick was offered $1 million for his project after Days of Heaven. Malick had an idea for a film that would be "a history of the cosmos up through the formation of the Earth and the beginnings of life."[19] The film was known as Q and included elements not in The Tree of Life such as a section set in the Middle East during World War I, and an underwater minotaur dreaming about the evolution of the universe.[20] One day, Malick "just stopped" working on the film.[20]

Decades later, Malick pitched the concept of The Tree of Life to River Road Entertainment head Bill Pohlad while the two were collaborating on an early version of Che. Pohlad recalled initially thinking the idea was "crazy", but as the film concept evolved, he came to feel strongly about the idea;[21] he ended up financing the film.[22] Producer Grant Hill was also involved with the film at an early stage.[22] During a meeting on a different subject involving Malick, his producer Sarah Green, Brad Pitt, and Pitt's Plan B Entertainment production partner Dede Gardner, Malick brought up Tree of Life and the difficulties it was having getting made.[23] It was "much later on" that the decision was made for Pitt to be part of the cast.[23]

The Tree of Life was announced in late 2005, with Indian production company Percept Picture Company set to finance it and Donald Rosenfeld on board as executive producer. The film was set to be shot partially in India, with pre-production scheduled to begin in January 2006.[24] Colin Farrell and Mel Gibson were at one stage attached to the project. Heath Ledger was set to play the role of Mr. O'Brien, but dropped out (due to recurring sicknesses) a month before his death in early 2008.[25]

For the roles of the three brothers, the production team spent over a year, seeing over 10,000 Texas students for the roles.[26] About 95% of the entire cast had no prior acting experience.[26]

In an October 2008 interview Jack Fisk, a longtime Malick collaborator, suggested that the director was attempting something radical.[27] He also implied that details of the film were a close secret.[28] In March 2009, visual effects artist Mike Fink revealed to Empire magazine that he was working on scenes of prehistoric Earth for the film.[29] The similarity of the scenes Fink describes to descriptions of a hugely ambiguous project entitled Q that Malick worked on soon after Days of Heaven led to speculation that The Tree of Life was a resurrection of that abandoned project.[30]

Filming

[edit]Principal photography began in Texas in 2008.[32] Cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki returned to work with Malick after collaborating with him on The New World. The film was shot in 1.85:1 and often used natural light.[33][34] The film used 35mm, 65mm, and IMAX formats.[34]

Locations included Smithville,[35] Houston, Matagorda,[36] Bastrop, Austin,[37] Dallas,[38] and Malick's hometown of Waco.[39]

The eponym of the film is a large live oak tree that was excavated from a property five miles outside Smithville.[40] The 65,000-pound tree and root ball were trucked into Smithville and replanted.[41][42][43][44]

The sets for The Tree of Life were unusual for a large scale film.[45] According to Brad Pitt, "A movie set is very chaotic. There [are] hundreds of people; there [are] generators and trucks. And this was a completely different experience — we had none of that." "There were no [camera] lights ... there were no generators and the camera was all hand-held so it was a very free-form, low-key experience."[45]

Malick would change different aspects of a scene between takes in order to create "moments of truth".[45]

Editing

[edit]Similar to many of Malick's films, the film had "teams of editors to put together different cuts, and finding and discarding entire story lines during the post-production process."[46] Malick used "unorthodox methods to edit the film".[47] One of the film's editors, Billy Weber said "Terry is willing to try anything. Absolutely anything. Sometimes we'd cut a character out of a scene, or cut all the dialogue out of a scene, just to see if it worked. And when you've worked with him for any length of time, you can even try that without asking him about it first. He's very open to looking at anything that you try."[47] This includes allowing film students from USC and University of Texas, as well as interns, to play a part in the editing process.[47] Some of them stayed on the film the whole time.[47]

In an unused ending for the film, Jack arrives as a boarding student at St. Stephen's Episcopal School, which Malick attended in the 1950s.[46]

Visual effects

[edit]After nearly thirty years away from Hollywood, famed special effects supervisor Douglas Trumbull contributed to the visual effects work on The Tree of Life. Malick, a friend of Trumbull, approached him about the effects work and mentioned that he did not like the look of computer-generated imagery. Trumbull asked Malick, "Why not do it the old way? The way we did it in 2001?"[48]

Working with visual effects supervisor Dan Glass, Trumbull used a variety of materials for the creation of the universe sequence. "We worked with chemicals, paint, fluorescent dyes, smoke, liquids, CO2, flares, spin dishes, fluid dynamics, lighting and high speed photography to see how effective they might be," said Trumbull. "It was a free-wheeling opportunity to explore, something that I have found extraordinarily hard to get in the movie business. Terry didn't have any preconceived ideas of what something should look like. We did things like pour milk through a funnel into a narrow trough and shoot it with a high-speed camera and folded lens, lighting it carefully and using a frame rate that would give the right kind of flow characteristics to look cosmic, galactic, huge and epic."[50] The team also included Double Negative in London. Fluid-based effects were developed by Peter and Chris Parks, who had previously worked on similar effects for The Fountain.[51]

A column in The New Yorker noted that the film credited Thomas Wilfred's lumia composition Opus 161, and that this was the source of the "shifting flame of red-yellow light" at the beginning and the end.[52]

Themes

[edit]Philosophical

[edit]Many reviewers have noted the philosophical and theological themes of the film. Catholic author and now bishop of the Diocese of Winona–Rochester Fr. Robert Barron, reviewing The Tree of Life for a Chicago Tribune blog, noted that "in the play of good and evil, in the tension between nature and grace, God is up to something beautiful, though we are unable to grasp it totally..."Tree of Life" is communicating this same difficult but vital lesson."[53] The Catholic magazine America called the film "a philosophical exploration of grief, theodicy and the duality of grace and human nature". They described the final beach scene as "the greatest film depiction of eschatological bodily resurrection".[54]

Rabbi David Wolpe says "that Terrence Malick's new film "Tree of Life" opens with a quotation from Job. That quotation holds the key to the film and in some sense, the key to our attitude toward life."[55] He added that "The agony of the parents, the periodic cruelty of the father — all are the powerful but passing dramas that for the moment entirely preoccupy us as we watch the movie. But then we are drawn back to a world so much bigger than our hour upon the stage that we know again how essentially small is each human story."[55]

According to Bob Mondello, the film is showing that "to understand the death of a young man, we need to understand everything that led to his creation, starting with creation itself."[56]

Kristen Scharold compared the film to Augustine's Confessions, and noted how one voiceover is nearly identical to a quote from Fyodor Dostoevsky's The Brothers Karamazov.[57]

Nature and grace

[edit]Many have said that Mr. O'Brien represents the way of nature, while Mrs. O'Brien represents the way of grace.[56][45]

Brad Pitt said Mr. O'Brien "represents nature — but nature as that oppressive force that will choke another plant out for its own survival."[45] "The American dream didn't work out as he believed it would. [He's] quite envious and bitter that people are ahead of him. Naturally, when someone feels oppressed, they find someone weaker to pass that oppression on[to], and the sadness in this situation [is] it's on his sons."[45]

Autobiographical

[edit]Many reviewers have noted the similarities between Jack's life and Terrence Malick's life. Jim Lynch, a close friend of Malick, told Malick that he thought The Tree of Life, Knight of Cups, and Song to Song, formed an "autobiographical trilogy".[46] Lynch said Malick disliked the labeling and "didn't want people thinking that he was just making movies about himself. He was making movies about broader issues."[46]

Release

[edit]

In March 2009, Empire magazine's website quoted visual effects supervisor Mike Fink as saying that a version of the film will be released for IMAX cinemas along with two versions for traditional cinemas.[29] The IMAX film has been revealed to be Voyage of Time, a documentary expanding on the "history of the universe" scenes in The Tree of Life, which the producers decided to focus on releasing at a later date so as not to cannibalize its release.[58] It was released in IMAX in the United States on October 7, 2016 by Broad Green Pictures.[59]

Delays and distribution problems

[edit]By May 2009, The Tree of Life had been sold to a number of international distributors, including EuropaCorp in France, Tripictures in Spain, and Icon in the United Kingdom and Australia,[60] but lacked a US distributor. In August 2009, it was announced that the film would be released in the US through Apparition, a new distributor founded by River Road Entertainment head Bill Pohlad and former Picturehouse chief Bob Berney.[61] A tentative date of December 25, 2009 was announced, but the film was not completed in time.[62] Organisers of the Cannes Film Festival made negotiations to secure a premiere at Cannes 2010, resulting in Malick sending an early version of the film to Thierry Fremaux and the Cannes selection committee.[63] Though Fremaux warmly received the cut and was eager to screen the film at his festival,[63] Malick ultimately told him that he felt the film was not ready.[64] On the eve of the 2010 Cannes Film Festival, Berney suddenly announced his departure from Apparition, leaving the company's future uncertain.[65] Pohlad decided to keep The Tree of Life at Apparition, and after significant restructuring, hired Tom Ortenberg to act as a consultant on its release. A tentative plan was made to release it in late 2010, in time for awards consideration.[66] Ultimately, Pohlad decided to close Apparition and sell rights to the film.[67] Private screenings of the film to interested parties Fox Searchlight Pictures and Sony Pictures Classics took place at the 2010 Telluride Film Festival.[68] On September 9, Fox Searchlight announced their acquisition of the film from Pohlad's River Road Entertainment.[69] The film opened in limited release in the United States on May 27, 2011.[70]

On March 28, 2011, UK magazine Empire reported that UK distributor Icon Entertainment was planning to release the film on May 4, 2011. This would make the UK the first region in the world to see the film,[71] preempting the expected Cannes Film Festival premiere on May 11. This would disqualify the film from inclusion at Cannes.[72] As a result, a surge of interest in the story developed on international film news sites.[71] After film blogger Jeff Wells was told by a Fox Searchlight representative that this was "unlikely",[73] and Anne Thompson received similar word from Searchlight and outright denial from Summit,[74][75] Helen O'Hara from Empire received a confirmation from Icon that they intended to stick with the May 4 release.[71] On March 31, Jeff Wells was told by Jill Jones, Summit's senior VP of international marketing and publicity, that Icon has lost the right to distribute The Tree of Life in the UK, due to defaulting on its agreement, with the matter pending arbitration at a tribunal in Los Angeles.[76] On June 9, it was announced that The Tree of Life would be released in the UK on July 8, 2011, after Fox Searchlight Pictures picked up the UK rights from Icon.[77]

Home media

[edit]The Tree of Life was released on Blu-ray Disc in the United States and Canada on October 11, 2011; on January 24, 2012, there was a separate release of the DVD.[78]

During the Cannes Film Festival in 2011, Peter Becker, president of the home media company The Criterion Collection, and Fox Searchlight discussed a potential Criterion home video release that would include a longer alternate version of The Tree of Life which Malick would like to create. In an unprecedented move, Criterion decided to finance the alternate version for its eventual inclusion on both Blu-ray and DVD. In creating the alternate version, the original negatives' palettes were located for Malick to use, the entire film scanned in 4K resolution, cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki brought in to help grade the footage, and a full sound mix created for the additional material, with Malick even dedicating "the better part of a year" to this project. Becker stated that the company has "never undertaken anything this extensive or this challenging, or anything that has taken this long to achieve or required so much effort on the part of pretty much every post-production craft. The only thing we didn't do is go shoot new material".[79]

Malick was careful to note that the extended cut of the film is an alternative version, not the definitive one. In an interview with Indiewire, Criterion technical director Lee Kline said:

Unlike with [The New World], [the version of The Tree of Life] that premiered in 2011 at Cannes [was] definitely the definitive version of the film he wanted to make. What's interesting talking to Terry about this [new version of Tree of Life], I think he still doesn't want people to think this is a better version. This is another version.[80]

The extended version runs to 188 minutes; in addition to entirely new footage with new characters and scenes, it also extends existing scenes and features minor changes to the film's score, musical arrangements, and color grading.[79] After premiering at the 75th Venice International Film Festival on September 7, 2018,[81] the extended cut was released on September 11, along with a new 4K digital restoration of the original version. Both editions also include the film's trailer, the making-of documentary Exploring "The Tree of Life", a 2011 interview with composer Alexandre Desplat, new interviews with actress Jessica Chastain, visual-effects supervisor Dan Glass, and music critic Alex Ross, and a 2011 video essay by Matt Zoller Seitz, as well as a booklet containing essays by film critics Kent Jones and Roger Ebert. The cover used for both editions is designed by Neil Kellerhouse.[82]

Soundtrack

[edit]The Tree of Life Original Motion Picture Soundtrack by Alexandre Desplat was released in 2011 by Lakeshore Records.[83] "The Tree of Life" features selections and snippets from more than 30 individual pieces—including works by Brahms, Mahler, Bach, Couperin, Górecki and Holst. They are all woven together seamlessly with the help of some original music by Alexandre Desplat.[84]

Reception

[edit]Critical response

[edit]Early reviews for The Tree of Life were polarized. After being met with both boos[85] and applause[86] at its premiere at the 2011 Cannes Film Festival,[87] the film received mixed early reviews.[88][89] It went on to be awarded the Palme d'Or. Two of its producers, Bill Pohlad and Sarah Green, accepted the prize on behalf of the reclusive Malick.[90] The Tree of Life is the first American film to win the Palme d'Or since Fahrenheit 9/11 in 2004.[90] The head of the jury, Robert De Niro, said it was difficult to choose a winner, but The Tree of Life "ultimately fit the bill".[90] De Niro explained, "It had the size, the importance, the intention, whatever you want to call it, that seemed to fit the prize."[90][91]

The Tree of Life has since garnered critical acclaim. On Rotten Tomatoes, 85% of critics have given the film a positive review based on 298 reviews, with an average rating of 8.2/10. The site's critics consensus reads "Terrence Malick's singularly deliberate style may prove unrewarding for some, but for patient viewers, Tree of Life is an emotional as well as visual treat."[92] On Metacritic, which assigns a weighted mean rating out of 100 reviews from film critics, the film has a rating score of 85 out of 100 based on 50 reviews, indicating "universal acclaim".[93]

Roger Ebert gave the film four stars of four and wrote:

The Tree of Life is a film of vast ambition and deep humility, attempting no less than to encompass all of existence and view it through the prism of a few infinitesimal lives. The only other film I've seen with this boldness of vision is Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey and it lacked Malick's fierce evocation of human feeling. There were once several directors who yearned to make no less than a masterpiece, but now there are only a few. Malick has stayed true to that hope ever since his first feature in 1973.[94]

The following year, Ebert gave The Tree of Life one of his ten votes in Sight & Sound's 2012 critics' poll of the world's greatest films.[95] Anthony Lane of The New Yorker said a "seraphic strain" in Malick's work "hits a solipsistic high" in The Tree of Life. "While the result will sound to some like a prayer, others may find it increasingly lonely and locked, and may themselves pray for Ben Hecht or Billy Wilder to rise from the dead and attack Malick's script with a quiver of poisonous wisecracks."[96]

Peter Bradshaw of The Guardian awarded it five stars and lauded it as an "unashamedly epic reflection on love and loss" and a "mad and magnificent film".[97] Todd McCarthy of The Hollywood Reporter states "Brandishing an ambition it's likely no film, including this one, could entirely fulfill, The Tree of Life is nonetheless a singular work, an impressionistic metaphysical inquiry into mankind's place in the grand scheme of things that releases waves of insights amidst its narrative imprecisions."[98] Justin Chang of Variety states the film "represents something extraordinary" and "is in many ways his simplest yet most challenging work, a transfixing odyssey through time and memory that melds a young boy's 1950s upbringing with a magisterial rumination on the Earth's origins."[1] Peter Travers of Rolling Stone states "Shot with a poet's eye, Malick's film is a groundbreaker, a personal vision that dares to reach for the stars."[99] A. O. Scott of The New York Times gave the film much praise and stated, "The sheer beauty of this film is almost overwhelming, but as with other works of religiously minded art, its aesthetic glories are tethered to a humble and exalted purpose, which is to shine the light of the sacred on secular reality". Total Film gave the film a five-star review (denoting 'outstanding'): "The Tree of Life is beautiful. Ridiculously, rapturously beautiful. You could press 'pause' at any second and hang the frame on your wall."[100] Richard Corliss of Time named it one of the Top 10 Best Movies of 2011.[101]

Some religious reviewers welcomed the spiritual themes of the film.[102][103][104][105] For instance, Catholic author and now auxiliary bishop of Los Angeles Fr. Robert Barron, reviewing The Tree of Life for a Chicago Tribune blog, noted that "in the play of good and evil, in the tension between nature and grace, God is up to something beautiful, though we are unable to grasp it totally..."Tree of Life" is communicating this same difficult but vital lesson."[53] Rabbi David Wolpe says "that Terrence Malick's new film "Tree of Life" opens with a quotation from Job. That quotation holds the key to the film and in some sense, the key to our attitude toward life."[55]

Not all reviews were positive. Sukhdev Sandhu, chief film critic of The Daily Telegraph describes the movie as "self-absorbed", and "achingly slow, almost buckling under the weight of its swoony poetry."[106] Likewise, Stephanie Zacharek of Movieline praised the technical aspects of the film, such as the "gorgeous photography", but nonetheless criticized it as "a gargantuan work of pretension and cleverly concealed self-absorption."[107] Lee Marshall of Screen Daily referred to the film as "a cinematic credo about spiritual transcendence which, while often shot through with poetic yearning, preaches too directly to its audience."[108] Filmmaker David Lynch said that, while he liked Malick's previous works, The Tree of Life "was not his cup of tea".[109] In 2016, John Patterson of The Guardian complained of the meager impression that the film left on him, opining that "much of it simply evaporates before your eyes."[110]

Sean Penn has said, "The screenplay is the most magnificent one that I've ever read but I couldn't find that same emotion on screen. ... A clearer and more conventional narrative would have helped the film without, in my opinion, lessening its beauty and its impact."[111] He further clarified his reservations about the film by adding, "But it's a film I recommend, as long as you go in without any preconceived ideas. It's up to each person to find their own personal, emotional or spiritual connection to it. Those that do generally emerge very moved."[112]

Top ten lists

[edit]The film appeared on over 70 critics' year-end top ten lists, including 15 first-place rankings.[113] The Tree of Life was voted best film of 2011 in the annual Sight & Sound critic poll, earning one and a half times as many votes as runner up A Separation.[114] The film also topped the critics poll of best released film of 2011 by Film Comment,[115] and the IndieWire annual critics survey for 2011,[116] as well as The Village Voice/LA Weekly Film Poll 2011.[117] In France, Cahiers du cinéma placed it second on its 2011 top ten list, tying it with The Strange Case of Angelica.[118] Keith Uhlich of Time Out New York named The Tree of Life the third-best film of 2011, writing that "it may be the best thing [Malick's] ever done."[119]

Other lists

[edit]In 2015, Bradshaw named the film one of the top 50 films of the decade so far by The Guardian.[120] The Tree of Life ranked 79th on the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC)'s 100 Greatest American Films in 2015,[121] as well as seventh in the 100 Greatest Films of the 21st Century in August 2016.[9] The latter list was compiled by polling 177 film critics from around the world.

In 2019, The Guardian ranked The Tree of Life 28th in its 100 best films of the 21st century list.[122] In December 2019, The Tree of Life topped The Associated Press' list of the best films of the 2010s.[8] In March 2020, America magazine put the film on its The Top 25 Films from the Last 25 Years.[54]

In 2022, the film was ranked #196 in the Sight and Sound Greatest Films of All Time poll.[10]

Accolades

[edit]The film won the Palme d'Or at the 2011 Cannes Film Festival.[123] The film was nominated for Academy Award for Best Picture, Academy Award for Best Director, and Academy Award for Best Cinematography at the 84th Academy Awards[124]

The film won the 2011 FIPRESCI (International Federation of Film Critics) Big Prize for the Best Film Of the Year. The award was presented on September 16, during the opening ceremony of the 59th San Sebastián International Film Festival.[125] Malick released a statement of thanks for the award.[126] On November 28, it was announced that the film had won the Gotham Award for Best Feature, shared with Beginners.[127]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The name of the city is not stated, but Malick's official first draft of the script states that Jack lives in the "City of Destruction," which he describes as "a modern city: it could be Chicago, New York, Houston, Paris, Mumbai, Los Angeles, or a composite of them all."[12] Scenes were shot in Houston and Dallas.[13]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Justin Chang (May 16, 2011). "Cannes Competition: The Tree of Life". Variety. Archived from the original on November 8, 2012. Retrieved February 18, 2020.

- ^ "The Tree of Life (12)". British Board of Film Classification. June 10, 2011. Archived from the original on July 7, 2013. Retrieved June 1, 2013.

- ^ "The Tree of Life". Box Office Mojo. IMDb. Archived from the original on January 25, 2021. Retrieved January 25, 2021.

- ^ "The Tree of Life". The Numbers. Nash Information Services, LLC. Archived from the original on March 6, 2018. Retrieved January 25, 2021.

- ^ Skiba, Justin (May 16, 2019). "Eight years ago today: The Tree of Life premieres at Cannes (May 16, 2011)". Two Ways Through Life - The Tree of Life (2011) Film Enthusiast. Archived from the original on January 12, 2021. Retrieved June 17, 2019.

- ^ "Film Critic Top 10 Lists - Best of 2011". Metacritic. Archived from the original on April 13, 2014. Retrieved June 3, 2014.

- ^ "Best of 2011". CriticsTop10. January 13, 2013. Archived from the original on December 2, 2016. Retrieved December 1, 2016.

- ^ a b Coyle, Jake; Bahr, Lindsey (December 13, 2019). "'Tree of Life' tops AP's best 10 films of the decade". AP News. Archived from the original on December 14, 2019. Retrieved July 31, 2020.

- ^ a b "The 21st Century's 100 Greatest Films". BBC Culture. August 23, 2016. Archived from the original on January 31, 2017. Retrieved August 16, 2016.

- ^ a b "The Tree of Life (2010)". BFI. February 9, 2022. Retrieved March 18, 2024.

- ^ Orr, Christopher (June 3, 2011). "'The Tree Of Life': A Beautiful, Lyrical Mess". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on May 9, 2022. Retrieved May 9, 2022.

- ^ a b Malick, Terrence (June 25, 2007). "The Tree of Life: A Screenplay by Terrence Malick (First Draft)" (PDF). Indieground Films. Retrieved October 10, 2024.

- ^ "Filming Locations for Terrence Malick's The Tree Of Life (2011), in Texas, Utah and Italy". The Worldwide Guide to Movie Locations. Retrieved December 9, 2024.

- ^ a b Bleasdale, John (September 15, 2018). "Exploring The Extended Edition of Terrence Malick's 'Tree of Life'". Film School Rejects. Retrieved October 10, 2024.

- ^ Hemphill, Jim (November 14, 2018). "How the New Version of The Tree of Life Changed My Mind About Director's Cuts". Talkhouse. Retrieved October 10, 2024.

- ^ Nero, Dom (September 19, 2018). "The Criterion Collection Edition of 'The Tree of Life' Isn't Just a Director's Cut. It's an Entirely New Film". Esquire. Retrieved October 10, 2024.

- ^ O'Falt, Chris (September 11, 2018). "'The Tree of Life': Two Versions of Terrence Malick's Masterpiece, Side by Side, and What Makes Them Different". IndieWire. Retrieved October 10, 2024.

- ^ Ebiri, Bilge (September 11, 2018). "Will Terrence Malick Ever Really Finish The Tree of Life?". Vulture. Retrieved October 10, 2024.

- ^ Ebiri, Bilge (May 13, 2011). "How Everything in Terrence Malick's Career Has Built Toward 'The Tree of Life' -- New York Magazine - Nymag". New York Magazine. Archived from the original on August 9, 2020. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- ^ a b The Playlist Staff (July 12, 2011). "The Lost Projects And Unproduced Screenplays Of Terrence Malick". IndieWire. Archived from the original on November 27, 2020. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- ^ Abele, Robert (September 9, 2009). "Pohlad holds out hope". Variety. Retrieved October 26, 2010.

- ^ a b Zeitchik, Steven; John Horn (January 24, 2012). "Oscars 2012: How will 'Tree of Life' be represented?". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on August 29, 2019. Retrieved January 26, 2012.

The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences said it had yet to determine which producers would be eligible for the best picture prize....it's likely that Bill Pohlad and Sarah Green will be two of the producers. Pohlad, who financed the film, had been developing it with Malick for about a decade, while Green is Malick's longtime producer and close confidant. The third slot could go to one of three people – Grant Hill, a producer who was involved with it early on; Brad Pitt, who came on to produce and then star; or Dede Gardner, Pitt's producing partner.

- ^ a b "The Tree of Life: A Conversation With Producer Dede Gardner". thehdroom.com. October 13, 2011. Archived from the original on February 29, 2012. Retrieved January 26, 2012.

- ^ Bhushan, Nyay (August 31, 2005). "Percept finds 'Life' with Malick feature". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on May 3, 2008. Retrieved March 29, 2008.

- ^ Naval-Shetye, Aakanksha (May 17, 2006). "Guess who's coming to town!". The Times of India. Archived from the original on November 5, 2012. Retrieved October 26, 2010.

- ^ a b Kavner, Lucas (June 11, 2011). "How Malick Built A Family In 'Tree Of Life'". HuffPost. Archived from the original on October 28, 2019. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- ^ "Arrival in The New World: Extended Cut". Blogtalkradio.com. October 29, 2008. Archived from the original on May 11, 2011. Retrieved January 26, 2012.

- ^ Lim, Dennis (January 6, 2008). "If You Need a Past, He's the Guy to Build It". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 8, 2017. Retrieved February 23, 2017.

- ^ a b Exclusive: Malick's Tree Of Life Archived May 30, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Empire. Retrieved December 22, 2010.

- ^ Terrence Malick's THE TREE OF LIFE To Go IMAX? With Dinosaurs? Archived October 2, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, aintitcool.com, March 2, 2009

- ^ "Visiting Texas – The Tree of Life Experience". Two Ways Through Life - The Tree of Life (2011) Film Enthusiast. April 25, 2019. Archived from the original on October 7, 2020. Retrieved December 15, 2019.

- ^ McNary, Dave (April 15, 2008). "Chastain to star opposite Pitt in 'Tree'". Variety. Archived from the original on July 6, 2008. Retrieved April 19, 2008.

- ^ B, Benjamin (August 2011). "The ASC -- American Cinematographer: Cosmic Questions". theasc.com. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- ^ a b "Emmanuel Lubezki AMC ASC / The Tree of Life". British Cinematographer. May 3, 2015. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- ^ "Filming Locations". Two Ways Through Life - The Tree of Life (2011) Film Enthusiast. April 22, 2019. Archived from the original on October 7, 2020. Retrieved June 17, 2019.

- ^ Garcia, Chris (March 25, 2008). "Gracia, Chris. "'Tree of Life' uprooted, briefly". austin360.com". Austin360.com. Archived from the original on March 29, 2012. Retrieved January 26, 2012.

- ^ "The Tree of Life (2011)". IMDb. Archived from the original on December 17, 2014. Retrieved January 12, 2015.

- ^ Wilonsky, Robert (December 16, 2010). "Terrence Malick Shot Tree of Life All Over Texas. Including, Turns Out, in Downtown". DallasObserver.com. Archived from the original on February 21, 2012. Retrieved January 26, 2012.

- ^ "Ingram, Emily. "Part of downtown Waco shut down for film shoot". wacotrib.com". Retrieved January 26, 2012.[dead link]

- ^ Skiba, Justin (June 15, 2019). "Rare footage of the tree in 'The Tree of Life' prior to relocation for filming- Part 1 of 3". Two Ways Through Life - The Tree of Life (2011) Film Enthusiast. Archived from the original on October 1, 2020. Retrieved June 17, 2019.

- ^ Hagerty, Terry. "Oak in 'Tree of Life' moved to downtown Smithville". The Bastrop Advertiser, February 9, 2008, pp 1A, 2A.

- ^ Tree of Life. February 16, 2008.[dead YouTube link]

- ^ Planting the Tree of Life. February 17, 2008.[dead YouTube link]

- ^ Skiba, Justin (June 16, 2019). "Rare footage of the tree in 'The Tree of Life' being transported to Smithville for filming- Part 2 of 3". Two Ways Through Life - The Tree of Life (2011) Film Enthusiast. Archived from the original on October 7, 2020. Retrieved June 17, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f "Pitt Plays The American Patriarch In 'Tree Of Life'". NPR.org. May 29, 2011. Archived from the original on October 4, 2019. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- ^ a b c d "The Not-So-Secret Life of Terrence Malick". Texas Monthly. March 10, 2017. Archived from the original on October 19, 2020. Retrieved August 6, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Ebiri, Bilge (September 11, 2018). "Will Terrence Malick Ever Really Finish The Tree of Life?". Vulture. Archived from the original on September 3, 2020. Retrieved August 6, 2020.

- ^ Keegan, Rebecca (April 25, 2010). "TCM Festival: Hollywood Visionary Douglas Trumbull Working on Terrence Malick Movie". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on June 15, 2011. Retrieved February 18, 2020.

- ^ "Filming Locations". Two Ways Through Life - The Tree of Life (2011) Film Enthusiast. April 22, 2019. Archived from the original on October 7, 2020. Retrieved December 15, 2019.

- ^ Hart, Hugh (June 17, 2011). "Video: Tree of Life Visualizes the Cosmos Without CGI". Wired. Archived from the original on November 5, 2013. Retrieved March 11, 2017.

- ^ "Animation World Network: Giving VFX Birth to Tree of Life". Archived from the original on September 2, 2011. Retrieved September 26, 2011.

- ^ Zinman, Gregory (June 27, 2011). "Lumia: Thomas Wilfred's Opus 161 (1965-66)". The New Yorker. New York, NY: Condé Nast. Archived from the original on January 23, 2016. Retrieved October 11, 2015.

- ^ a b "The Seeker: Tree of Life glorifies God". Newsblogs.chicagotribune.com. May 25, 2011. Archived from the original on March 27, 2014. Retrieved June 3, 2014.

- ^ a b Senechal, Isabelle; Di Corpo, Ryan; Dulle, Colleen (March 27, 2020). "The Top 25 Films from the Last 25 Years". America Magazine. Archived from the original on August 7, 2020. Retrieved August 1, 2020.

- ^ a b c "The Religious Meaning of Malick's 'Tree of Life'". The Huffington Post. May 31, 2011. Archived from the original on April 23, 2015. Retrieved January 12, 2015.

- ^ a b Mondello, Bob (May 27, 2011). "Symphonic Style Roots Malick's 'Tree Of Life'". NPR. Archived from the original on September 15, 2020. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- ^ Scharold, Kristen (June 2011). "The Tree of Life". Books & Culture. Archived from the original on November 28, 2020. Retrieved August 6, 2020.

- ^ Horn, John (May 25, 2011). "Terrence Malick looks to IMAX to extend 'Tree of Life' explorations". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on May 28, 2011. Retrieved May 28, 2011.

- ^ Fleming, Mike Jr. (February 3, 2015). "IMAX, Broad Green Sign On As Distribs Of Terrence Malick's 'Voyage Of Time'". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on March 28, 2016. Retrieved April 10, 2016.

- ^ "TriPictures picks up Summit's Tree of Life, Letters to Juliet". Screen Daily. May 22, 2009. Archived from the original on June 16, 2010. Retrieved October 26, 2010.

- ^ Fleming, Michael (August 6, 2009). "Pohlad, Berney unveil Apparition". Variety.

- ^ Thompson, Anne (October 15, 2009). "Tree of Life Will Not Open in 2009". Indiewire. Archived from the original on October 18, 2009.

- ^ a b Thompson, Anne (April 20, 2010). "Cannes Updates: Fortnight, Critics Week, Carlos, Tree of Life". Indiewire. Archived from the original on June 27, 2010. Retrieved October 26, 2010.

- ^ Davis, Edward (April 15, 2010). "Don't Get Those 'Tree of Life' Hopes Up for Cannes 2010". The Playlist. Archived from the original on March 17, 2012. Retrieved October 26, 2010.

- ^ Fleming, Michael (May 11, 2009). "Berney Exit Blindsides Apparition". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on April 15, 2013. Retrieved February 18, 2020.

- ^ Fleming, Mike (June 30, 2010). "Apparition Restructures With 60% Staff Cut". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on July 5, 2010. Retrieved October 26, 2010.

- ^ Fleming, Michael (September 7, 2010). "Apparition Cuts Staff, Nears 'Tree of Life' Distribution Deal". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on November 8, 2010. Retrieved October 26, 2010.

- ^ Thompson, Anne (September 13, 2010). "Waiting for Malick: Which Film Fest Will Debut Tree of Life?". Archived from the original on October 18, 2010. Retrieved October 26, 2010.

- ^ "Announced: Fox Searchlight Acquires Terrence Malick's TREE OF LIFE". Fox Searchlight Pictures. September 9, 2010. Archived from the original on September 11, 2010. Retrieved September 9, 2010.

- ^ Jagernauth, Kevin (October 22, 2010). "'The Tree Of Life' Gets May 27, 2011 Release Date". indieWire. Archived from the original on October 25, 2010. Retrieved October 22, 2010.

- ^ a b c O'Hara, Helen (March 28, 2011). "The Tree of Life has A UK Release Date". Empire. Archived from the original on May 16, 2011. Retrieved April 2, 2011.

- ^ "Rules & Regulations 2011". Archived from the original on December 3, 2010. Retrieved April 2, 2011.

- ^ Wells, Jeff (March 28, 2011). "UK Tree of Life Release: Shocker or Snafu?". Hollywood Elsewhere. Archived from the original on June 28, 2011. Retrieved April 2, 2011.

- ^ Thompson, Anne (March 28, 2011). "Tree of Life Will Not Open in the U.K. Before Cannes After All, Gets New Poster". Indiewire. Archived from the original on April 30, 2011. Retrieved April 2, 2011.

- ^ Thompson, Anne (March 31, 2011). "Summit Takes Icon UK to a Los Angeles Arbitration Tribunal Over Tree of Life". Indiewire. Archived from the original on April 2, 2011. Retrieved April 2, 2011.

- ^ Wells, Jeff (March 28, 2011). "Icon Kicked to Curb". Hollywood Elsewhere. Archived from the original on April 2, 2011. Retrieved April 2, 2011.

- ^ "New Tree Of Life Featurette Online and finally gets a UK release date". Empire. June 9, 2011. Archived from the original on May 30, 2013. Retrieved February 18, 2020.

- ^ "The Tree of Life Blu-ray". Blu-ray.com. Archived from the original on January 26, 2012. Retrieved January 26, 2012.

- ^ a b Debruge, Peter (May 11, 2018). "Terrence Malick's 'Tree of Life' Gets Longer Criterion Version". Variety. Variety Media, LLC. Archived from the original on May 17, 2018. Retrieved May 17, 2018.

- ^ O'Falt, Chris (August 31, 2018). "Criterion's 'The Tree of Life' Is Not a Director's Cut, but a New Movie From Terrence Malick". Indiewire. Archived from the original on October 7, 2018. Retrieved January 4, 2019.

- ^ "Biennale Cinema 2018 | The Tree of Life (Extended Cut)". La Biennale di Venezia. August 7, 2018. Archived from the original on August 11, 2020. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ^ "The Tree of Life (2011)". The Criterion Collection. The Criterion Collection. Archived from the original on May 17, 2018. Retrieved May 16, 2018.

- ^ Skiba, Justin (May 4, 2019). "The Tree of Life (2011) Soundtrack". Two Ways Through Life - The Tree of Life (2011) Film Enthusiast. Archived from the original on January 12, 2021. Retrieved June 17, 2019.

- ^ "Terrence Malick's 'Tree of Life': The classical music factor | Culture Monster | Los Angeles Times". July 5, 2011. Archived from the original on September 21, 2019. Retrieved November 16, 2019.

- ^ "Movie Starring Pitt, Penn Booed at Cannes" Archived March 22, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, Evann Gastaldo. Newser. May 16, 2011. Retrieved September 10, 2011

- ^ "Brad Pitt, Terrence Malick's "Tree of Life" booed in Cannes". May 16, 2011. Archived from the original on May 30, 2012. Retrieved November 5, 2011.

- ^ Skiba, Justin (May 16, 2019). "Eight years ago today: The Tree of Life premieres at Cannes (May 16, 2011)". Two Ways Through Life - The Tree of Life (2011) Film Enthusiast. Archived from the original on January 12, 2021. Retrieved June 17, 2019.

- ^ Ditzian, Eric (May 16, 2011). "'The Tree Of Life': The Cannes Reviews Are In! Director Terrence Malick's first film since 2005 is getting widely mixed reactions after its Cannes premiere". Mtv. Archived from the original on June 19, 2012. Retrieved January 26, 2012.

- ^ "'Tree of Life' Sets Off Mixed Frenzy of Boos, Applause, Glowing Reviews (Cannes 2011)". The Hollywood Reporter. May 16, 2011. Retrieved January 26, 2012.

- ^ a b c d Germain, David (May 22, 2011). "Malick's 'Tree of Life' wins top Cannes fest honor". Forbes. Retrieved May 22, 2011.[dead link]

- ^ Gritten, David (May 24, 2011). "The Tree of Life demands to be seen and experienced". The Daily Telegraph. UK. Archived from the original on May 26, 2011. Retrieved May 27, 2011.

- ^ "The Tree of Life". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Archived from the original on October 29, 2020. Retrieved January 15, 2023.

- ^ "The Tree of Life". Metacritic. Fandom, Inc. Archived from the original on October 2, 2018. Retrieved January 15, 2023.

- ^ "The Tree of Life". Chicago Sun-Times. June 2, 2011. Archived from the original on April 7, 2019. Retrieved August 22, 2019.

- ^ "The greatest films of all time". Chicago Sun-Times. April 26, 2012. Archived from the original on June 18, 2019. Retrieved February 18, 2020.

- ^ Lane, Anthony (May 30, 2011). "Time Trip". The New Yorker. Condé Nast. Archived from the original on February 26, 2015. Retrieved February 24, 2015.

- ^ "The Tree of Life". The Guardian. London. December 16, 2010. Archived from the original on September 15, 2019. Retrieved November 25, 2019.

- ^ Todd McCarthy (May 16, 2011). "The Tree of Life: Cannes Review". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on January 28, 2020. Retrieved February 18, 2020.

- ^ Peter Travers (May 26, 2011). "The Tree of Life". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on February 3, 2012. Retrieved January 26, 2012.

- ^ "The Tree Of Life Review". Total Film. Archived from the original on July 11, 2011. Retrieved July 21, 2011.

- ^ Corliss, Richard (December 7, 2011). "The Top 10 Everything of 2011 – The Tree of Life". Time. Time Inc. Archived from the original on January 7, 2012. Retrieved December 13, 2011.

- ^ Hibbs, Thomas S. (July 5, 2011). "A Story From Before We Can Remember: A Review of Tree of Life | Web Exclusives | Daily Writings From Our Top Writers". First Things. Archived from the original on April 4, 2014. Retrieved June 3, 2014.

- ^ Ian Marcus Corbin (June 5, 2012). "Points of Light". The New Atlantis. Archived from the original on March 7, 2015. Retrieved June 3, 2014.

- ^ Hart, David Bentley (July 22, 2011). "Seven Characters in Search of a Nihil Obstat". First Things. Archived from the original on April 26, 2015. Retrieved January 12, 2015.

- ^ Leithart, Peter J. (2013). Shining Glory: Theological Reflections on Terrence Malick's Tree of Life. Eugene, Oregon: Cascade Books. ISBN 978-162032-413-4.

- ^ Sukhdev Sandhu (July 7, 2011). "The Tree Of Life, review". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on May 17, 2018. Retrieved April 2, 2018.

- ^ Stephanie Zacharek. "CANNES REVIEW: Tree of Life Is All About Life; But Does Malick Care Much for People?". Movieline. Archived from the original on May 21, 2011. Retrieved May 16, 2011.

- ^ Lee Marshall. "The Tree Of Life". Screen Daily. Archived from the original on May 21, 2011. Retrieved May 16, 2011.

- ^ Zeitchik, Steven (June 22, 2012). "David Lynch says he doesn't have any ideas for a new film". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 3, 2018. Retrieved February 18, 2020.

- ^ Patterson, John (May 2, 2016). "Terrence Malick: has the legendary visionary finally lost the plot?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on March 13, 2017. Retrieved March 14, 2017.

- ^ Sean Penn on The Tree of Life: 'Terry never managed to explain it clearly' Archived April 11, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, The Guardian

- ^ Penn on Malick, part deux Archived January 12, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, InContention

- ^ "Film Critic Top 10 Lists – Best of 2011". Metacritic. Archived from the original on January 9, 2012. Retrieved January 26, 2012.

- ^ Lodge, Guy (November 28, 2011). "'Tree of Life' easily tops Sight & Sound's Best of 2011 poll". In Contention. Archived from the original on November 29, 2011. Retrieved November 29, 2011.

- ^ Kemp, Nicholas (December 16, 2011). "Film Comment". Archived from the original on January 8, 2012. Retrieved December 16, 2011.

- ^ "indieWIRE". Archived from the original on January 3, 2012. Retrieved December 19, 2011.

- ^ "LA Weekly". Archived from the original on December 31, 2011. Retrieved December 21, 2011.

- ^ "Top Ten 2011, Décembre 2011 n°673". Cahiers du cinéma. Archived from the original on February 28, 2018. Retrieved February 27, 2018.

- ^ Uhlich, Keith (December 13, 2011). "The Best (and Worst) Films of 2011: Keith Uhlich's Picks". Time Out New York. Archived from the original on June 22, 2020. Retrieved June 16, 2020.

- ^ Bradshaw, Peter (January 5, 2015). "Peter Bradshaw's top 50 films of the demi-decade". The Guardian. Archived from the original on May 29, 2015. Retrieved April 29, 2015.

- ^ "The 100 greatest American films". BBC. July 20, 2015. Archived from the original on September 16, 2016. Retrieved February 17, 2017.

- ^ "The 100 best films of the 21st century". The Guardian. September 13, 2019. Archived from the original on September 13, 2019. Retrieved September 17, 2019.

- ^ "THE TREE OF LIFE". Festival de Cannes. May 16, 2011. Archived from the original on September 30, 2020. Retrieved July 31, 2020.

- ^ "THE 84TH ACADEMY AWARDS | 2012". Oscars. October 7, 2014. Archived from the original on April 17, 2018. Retrieved July 31, 2020.

- ^ "FIPRESCI, the International Federation of Film Critics". Archived from the original on February 24, 2011. Retrieved April 17, 2019.

- ^ "Sean Penn Has Issues But Recommends 'Tree Of Life'; Malick Says 'Burial' Is "Rushing Toward A Mix"". The Playlist. August 22, 2011. Archived from the original on November 7, 2011. Retrieved November 5, 2011.

- ^ Szalai, Georg (November 28, 2011). "Gotham Awards 2011: 'Tree of Life', 'Beginners' Tie for Best Feature". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on November 30, 2011. Retrieved November 28, 2011.

External links

[edit]- The Tree of Life at IMDb

- The Tree of Life at Rotten Tomatoes

- The Tree of Life: Let the Wind Speak an essay by Kent Jones at the Criterion Collection

- 2011 films

- 2011 fantasy films

- 2011 independent films

- 2011 science fiction films

- 2010s American films

- 2010s English-language films

- American coming-of-age films

- American drama films

- American independent films

- American nonlinear narrative films

- English-language fantasy films

- English-language independent films

- English-language science fiction films

- Films about evolution

- Films about father–son relationships

- Films about religion

- Films directed by Terrence Malick

- Films produced by Brad Pitt

- Films produced by Dede Gardner

- Films produced by Grant Hill (producer)

- Films scored by Alexandre Desplat

- Films set in Texas

- Films set in the 1950s

- Films shot in Houston

- Films shot in Texas

- Fox Searchlight Pictures films

- Magic realism films

- Metaphysical fiction films

- Palme d'Or winners

- Plan B Entertainment films

- River Road Entertainment films

- Satellite Award–winning films

- Works about meaning of life